Dissertation Final2

-

Upload

tone-langengen -

Category

Documents

-

view

243 -

download

2

Transcript of Dissertation Final2

To what degree and in what ways do MPs use Facebook for constituency

representation? What can explain the differences in such usage?

By Tone Langengen

This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the BSc in Politics with Economics, Friday 15th

of April 2016.

Contents

Introduction 3

Literature Review 7

Methods and Data 14

Data Analysis 19

Discussion and Conclusion 39

Appendix: Code Book 45

Bibliography 68

2

1. Introduction

Representation is a fundamental part of the British political system. It

constitutes the foundation of the parliamentary system and is integral in the

workings of the legislative process. Representation has also traditionally been

very important for the citizens of the UK. As there is little tradition for direct

participation, people have to a great extent relied on their representatives in

parliament for expressing their views and grievances (Judge 1993; 1999a). The

institutional context has opened for two main paths through which the people

are represented. Firstly, historical developments combined with the

parliamentary nature of the British political system have made parties one of

the main representational paths. The political parties represent the views of the

citizens by presenting them with policy alternatives before elections, and

subsequently discipline the elected officials to ensure that they stick to these

policy programs. Secondly, the Single Member Plurality electoral system

combined with a tradition of geographic representation means that each

constituency has one MP that represents it. This constituency representational

link is non-partisan in nature, as MPs are representing the whole constituency

from which they are elected and not just their supporters within it (Norton

2012). Together these two dimensions, the party and the constituency

dimension, form the strong representational basis of the UK parliament.

In modern Britain, the party has traditionally been regarded as the primary

basis of representation and their position as the link between the people and

state has traditionally been trusted and respected (Lawson 1980; Dalton, Farrell

and McAllister 2011). Developments in the last few decades have however

3

resulted in a waning of this representational basis. Firstly, there has been seen a

tendency of declining importance of political parties in the British system

(Katz and Mair 1995; Scarrow 2000). Throughout the last decades there has

been witnessed a general partisan dealignment in Britain (Dalton 2000; Dalton

et al. 2000) that has led to declining numbers of members and activists in the

parties (Van Biezen and Poguntke 2014; van Biezen et al. 2012; Katz et al.

1992). Parties have thus evolved from being mass parties relying greatly on the

activities and finance of its members, to becoming increasingly

professionalised, centralised and personalised (Farrell and Webb 2000; Katz

and Mair 1995; Webb 1994). These changes are conceptualised to weaken the

parties’ capacity to generate political integration and legitimacy, thus

weakening the parties’ representative capabilities (Scarrow 2000, p.83; Katz

and Mair 1995; Mair 2006). This opens for the possibility, and perhaps even

necessity, to strengthen the second line of representation.

The party decline has occurred simultaneously with a decreasing level of trust

in politicians and political institution, and increased disenchantment with

politics as a result of a number of scandals. Most recently, this was fuelled by

the 2009 expenses scandal, which saw the level of trust in politicians among

the population plummet (Curtice and Park 2010). Politicians as a group are as a

consequence of this being conceived as being unrepresentative of the

population, but rather acting in their own self-interest, making people feel

increasingly alienated from Westminster politics (Cairney 2014; Allen and

Cairney 2015). In this time of scandal, parties have proven themselves unable

to mend the relationship with the people and regain their trust. People are

4

increasingly seeing parties as untrustworthy and unrepresentative organisations

only interested in collecting as many votes as possible (Curtice and Park 2010;

Dalton and Weldon 2005). In spite of this unfavourable view of parties,

political institutions and politicians in general, there is evidence showing that

the people’s views about their local MP can often exist independently of the

views of the House of Commons in general (Norton 2005, pp. 195-196; Norton

2012). There might thus be an opportunity for MPs to use the constituency

dimension to remain popular and trusted, and rebuild the population’s trust in

the system.

The party decline and increased distrust and disenchantment with traditional

party politics show that the traditional, party line of representation is

increasingly loosing its importance. MPs might thus both have the opportunity

and the reason to establish a personal reputation independent of the party and

focus more on the constituency in their representational activities. MPs can use

the constituency representation dimension to bridge a representational gap and

establish trust in the political system.

One possible line through which MPs can establish and expand a

representational relationship with its constituency in the modern world is

through social media. The UK population is increasingly using social media to

connect with people, read about news, and discuss politics. In 2015 it was

estimated that the average UK citizen spends 1 hour and 40 minutes browsing

social media sites every day (Davidson 2015). Social media is also increasingly

used by MPs, with increasing numbers of them having such sites1. Social 1 Figures can be found in Chapter 4.

5

media does consequently establish a platform with opportunities for

representation, as it opens for communication with a large group of people on a

platform they frequently use. In the light of this, I will through this dissertation

attempt to answer two questions. Firstly, to what degree and in what ways do

MPs use Facebook for constituency representation? And secondly, what can

explain the differences in such usage? Through a discussion of this, I will be

able to shed some light on how constituency representation on Facebook

occurs, and whether there are further possibilities for constituency

representation on Facebook.

6

2. Literature Review: Representation, Constituency

Service and Social Media

The representation literature identifies many different forms of political

representation. For the sake of this dissertation, there are two main lines of

representation that are important. The first is the party dimension. This

describes a party-focused way of representing the population. Following this

model, individual MPs from the different parties engage in ‘general

representation’ through sticking to the party programs and defending the

interests of countrywide groups (Norton 2012, p. 404). The second line of

representation that is important for this dissertation is the constituency

dimension, which is the MPs’ representation of the geographic area from which

they are elected. This can also be called ‘specific’ representation, as it entails

that the MP defend and advance the interests of the constituency and the

individuals within it (Ibid).

These dimensions establish two different ways in which MPs can chose to act

as representatives. Representation theory suggests that British MPs are likely to

focus mainly on the general, party dimension of representation. This is because

there is a strong party tradition within the British system that naturally makes

parties very important for British MPs (Coxall and Robins 1998; Judge 1999b).

It also makes strategic sense for the individual MP to focus on the party, as it is

the local party that selects who will run to be the MP in each constituency and

the constituents arguably decides who to elect based on the party they

represent. This thus means that it is the party reputation that matters the most,

and that the MP has low incentives to nurture a personal reputation among

7

constituents and focus their representation on them (Searing 1994; Carey and

Shugart 1995; André and Depauw 2013). According to representation theory,

the party model thus becomes both the natural and the rational choice for MPs.

The tradition for the ‘specific’, constituency representation does regardless of

these incentives stand strong in the British context, and there is evidence

showing that the constituency link has become stronger in the latter part of the

20th century. One of the main ways in which MPs cultivate the ‘specific’

constituency dimension of representation is through constituency service.

Constituency service includes doing casework, reaching out to constituents to

seek out their opinions and find out about their problems, and spread

information about what they do and what they believe (Fenno 1978; Cain et al.

1987). In a study of constituency service in Britain, Cain et al. (1987) found

that MPs spend a significant, and increasing, amount of time on constituency

service, through doing more casework, holding more surgeries and publicizing

their work. In the years after, Wood and Norton (1992), Norton and Wood

(1990; 1993) and Searing (1994) conducted studies confirming that MPs

devote a lot of time to constituency service. It was found that while surgeries

used to be relatively rare and MPs only used to receive a dozen letter a week in

the 1950s, the 1980s and 90s saw the constituency role of the MP becoming

increasingly important with surgeries becoming a regular occurrence, the

number of letters an MP received increasing to about 20 to 50 a day, and MPs

increasingly appearing in local media and writing newsletters to constituents

(Norton 2005, p.182; Norton 2012, pp.406, 411). MPs estimated in 1996 that

they used about 40% of their time each week in parliament on constituency

8

work, in 2006 this estimate was even higher at 49% for new MPs (Norton

2012, p. 407; Rosenblatt 2006, p.32). These developments have therefore made

scholars like Norton (1994) suggest that the constituency role is becoming the

dominant role in the House of Common.

With the introduction of the internet, MPs communication with constituents

has become easier. A main issue for MPs has been that contact with

constituents on an extensive basis has been limited by time and costs. MPs

have lacked the resources to survey constituents’ opinions and distribute

printed material. The internet has however transformed the potential for MPs to

contact constituents, as it has opened for a low-cost and less time consuming

direct link between constituents and the MP (Zittel 2003; Ward and Lusoli

2005; Norton 2012). This has been acknowledged by parliament, and MPs

were in 2011 granted £10,000 to develop websites and produce other material

about their parliamentary work. All MPs now have an official email that is

open for the public, constituents can follow their local MPs action through a

website (theyworkforyou.com), and many MPs send out e-newsletters and have

e-mail lists to let their constituents keep up with their work. Most MPs have

additional personal websites, some have blogs and many use social media sites

such as Facebook and Twitter (Norton 2012, pp.414-415).

Some studies have been done on how MPs utilise ICTs to perform constituency

service. These studies (Ward and Lusoli 2005; Francoli and Ward 2008;

Norton 2007; Williamson 2009) have found that MPs use websites and blogs as

an extension of the constituency service to disseminate information to

9

constituents. It was found that MPs to a small degree encourage dialogue with

constituents and that few keep up to date on replying to comments, therefore

only using the platform for one-way communication with constituents. Studies

on web 2.0, social media platforms have to a great extent confirmed the

findings on web 1.0; these sites are used for constituency service, but it is done

in a one-way, promotional fashion (Jackson and Lilleker 2009; 2011). Despite

the finding that the internet is used for constituency service, most of the studies

(eg. Norton 2007; Jackson and Lilleker 2009; Francoli and Ward 2008) have

argued that ICT mainly is employed to bolster the role of the party in the

system, and that the possibilities for constituency service remains largely

untapped.

Despite research finding that the internet is still mainly used as an extension of

the party dimension, it can be assumed that there are more opportunities within

its use for constituency service. Ward, Lusoli and Gibson (2007) have

suggested that the very decentralised nature of the internet makes it a challenge

to the party-based model. Jackson and Lilleker (2011) have also made a similar

comment in their study of Twitter, noting that it is a platform that facilitates

MP to focus less on promoting the party and more on promoting themselves.

Such findings therefore suggest that the constituency role appears to be, and

has the potential, to grow in the online dimension (Jackson 2003; Jackson and

Lilleker 2009; Ward and Lusoli 2005; Williamson 2009). Especially web 2.0

applications have been highlighted for its potential for changing the

relationship between MPs and constituents (Jackson and Lilleker 2009). These

platforms have created a richer experience for users, making social media have

10

the potential to become an effective platform for constituency service.

Facebook is therefore arguably a very suitable platform for constituency

representation. Firstly, the population has been found to want to communicate

with parliament on platforms ‘where they are’ (Digital Democracy

Commission 2015). With about 30 million monthly users in the UK (Statista

2016), it can be claimed that Facebook is where the population ‘is’, making it a

good platform to reach them. Facebook does secondly have some affordances

in terms of representation. Facebook has been shown to expand the flow of

information to networks and enable more symmetrical conversations among

users (Halpern and Gibbs 2013). The feature of pages is for instance a way in

which people can connect to an MP by ‘Liking’ a page, and through this action

they will automatically receive the updates from this page straight to their

newsfeed without actively approaching the page. Within these pages people

can easily comment on what has been posted by the page owner, and others can

see what people have posted, thus opening for communication among people as

well as with the page owner (Halpern and Gibbs 2013; Vitak et al. 2011).

Facebook therefore constitutes an easy and available platform for

communication between MPs and constituents.

There is therefore reason to investigate how and to what degree Facebook is

used for constituency service, both to find out how it is used and to try to

identify opportunities for further use. To my knowledge, very few studies have

been done on Facebook and constituency representation2. There exists a

substantial amount of research on MPs use of Facebook during campaigns, but

how Facebook is used between elections for representation has been more or 2 Jackson and Lilleaker (2009) include Facebook in their analysis of Web 2.0 platform usage.

11

less a neglected area thus far. Some assumptions about how social media is

used for representation can nevertheless be made from previous research on

social media in general and constituency service online and offline. A number

of studies have shown that the affordances of Facebook lead to more focus on

the individual politicians rather than the party (Enli and Skogerbø 2013). There

might therefore be a reason to expect that Facebook to a great extent will be

used in a personal way (Enli and Skogerbø 2013; Enli and Thumin 2012;

Strömback 2008; Lilleker 2010), and there might also be reason to assume that

the lack of party focus will be replaced by constituency focus (Jackson and

Lilleker 2009; Norton 2007). Another assumption that can be made is that there

will be very few MPs who engage in two-way communication. Previous

studies have shown that there is very little two-way communication between

MPs and constituents on social media in campaigns (eg. Ward et al. 2003;

Karlsen 2009), supporting the previous research on web 1.0 (and 2.0) and

constituency service findings that there is little two-way communication also

between elections (Norton 2007; Jackson and Lilleker 2009; 2011). It can

therefore also be assumed that most MPs will ‘talk at’ their constituents, rather

than ‘engaging with’ them.

Based on these assumptions, this dissertation will explore how Facebook is

used by MPs. This will be done by analysing data based on the analysis of the

MPs Facebook pages to investigate, quantitatively, how Facebook is used.

Through the data analysis, it will primarily investigate whether Facebook is

used to focus on constituents, the ‘specific’ dimension of representation, or

whether it is rather focused on the party, the ‘general’ dimension of

12

representation. It will also look at some of the content of MPs’ posts to find out

whether MPs report on activities in parliament and political views on

Facebook. It will finally investigate how Facebook is used, whether MPs are

engaging in two-way communication through Facebook, and whether they are

personal in their communication, as well as investigating whether posts are

easily accessible for the population, making it more likely that they will read it.

Through this work this dissertation will give an image of how British MPs

communicate with their constituents via Facebook.

13

3. Methods and Data

The data on MPs Facebook usage was collected during February and March

2016. It includes all 650 MPs, with information missing on one3. The dataset

consists of information about the MPs: their gender, age, party, constituency,

nation, majority, number of years in office, year first elected and parliamentary

position. This is collected from the parliament’s official website and from the

British Election Study data (Parliament.uk 2016; British Election Study 2015).

The dataset also consists of information about MPs’ social media usage:

whether they have a Facebook page, Twitter profile and Website, number of

Facebook likes, number of posts in one month and data on their posts in this

period. Having an active Facebook page is defined as having posted anything

on Facebook since September 2015, therefore excluding pages used for

campaigning rather than representation.

The data on MPs’ Facebook usage was collected during the first weeks of

March. The data analysis contains all posts on MPs Facebook pages in the

period between 29th of January to 29th of February. The information in the posts

was coded in to 7 categories focusing on the content, style and focus of the

posts. The categories are based on previous literature on representation,

analysis of MPs’ online activities, and the Report of the Speaker’s Commission

on Digital Democracy.

3 Harry Harpman, Labour MP for Sheffield, Brightside and Hillsborough, died on the 4th of February 2016. No by-election was held for his constituency before this dissertation was finished.

14

Variables

The following section describes the categories the MPs Facebook posts have

been coded into. The full codebook can be found in the Appendix.

Constituency focus

The first coding category analyses whether the focus of the post is on the

constituency. The focus of the communication shows who the MP wishes to

reach, and who will feel like the recipient of the communication and thus be

more likely to engage with it. If the message of the MPs communication is

focused on the constituency, for instance through referring to casework,

sharing local information, and asking for constituents’ views on an issue, the

representational focus of the MP is on the constituency (Wahlke et al. 1962;

Eulau and Karps 1977; Jackson and Lilleker 2009).

Focus on all voters in the constituency

Representation literature recognises that representatives will often tend to focus

on their own supporters, usually based on party, rather than everyone in the

constituency (Esaiasson and Holmberg 1996; Esaiasson 2000; Fenno 1978).

The role of a constituency representative is nevertheless to represent the whole

of the constituency, not just one group. Coding this will provide some

information about whether the MP is representing the constituency, or whether

the focus is primarily on the party. This category will therefore measure the

number of posts where all constituents, not just certain groups, are the focus of

the posts. This consequently excludes any post referencing only the party

15

supporters in the constituency, for instance clearly criticising the other party or

referring to party specific events in the constituency.

Activities in Parliament

The third category of the index deals with the content of the posts. An

important part of a MP’s job is to be in the House of Commons and represent

his constituency and the party there (Fenno 1978; Cain et al. 1987).

Communicating this activity to constituents is therefore important to show their

constituents that they are qualified to be the constituency’s representative in

parliament, by presenting their views in parliament and standing up for the

constituency. Examples of such communication is explaining votes, showing

footage from debates, or referencing something that happened in parliament.

Political Views

Another content aspect of constituency representation is presentation of

political views. By providing this information to the constituents, they become

more familiar with the political placement of their local MP and get the chance

to ask for clarification of these views (Fenno 1978; Cain et al. 1987). Sharing

information about political views can for instance be done through providing a

link to a website with the MPs political views or through making posts about

causes that are important for the MP.

Online Responsiveness

Responsiveness, opening up for feedback from the constituents, is generally

regarded as a key aspect of being a constituency representative (Fenno 1978;

16

Jackson and Lilleaker 2009; Cain et al. 1987; Norton and Wood 1993). By

opening up for two-way communication with constituents, MPs can find out

about the opinions of the citizens and identify common issues and problems, as

well as give off an appearance of accessibility, which is assumed to increase

trust (Fenno 1978; Cain et al. 1987). This measure will find out whether MPs

use Facebook to replicate traditional means of communication with

constituents, or exploit the possibilities of the medium to engage with

constituents in new ways (Norton 2012; Jackson and Lilleker 2009). It will be

measured by whether the MP replies to comments on the page and/or uses

other tools to be interactive with constituents on Facebook as outlined in the

codebook.

Personalisation

Making communication on social media more ‘personal’, making it appear to

come directly from the MP and his or her close co-workers, is another aspect to

representing the constituency. Through personal posts MPs open for

constituents to identify with them by giving them a sense of familiarity and the

image of them as an ordinary human being, hopefully making the visitor

emphasise, engage with and like them (Fenno 1978; Jackson and Lilleker 2009;

2011; Auty 2005; Jackson 2008). This ‘personalisation’ on social media must

include using personal pronoun in posts and include photos of the candidate

taken in less formal settings.

17

Accessibility

According to the Digital Democracy Commission (2015), which has surveyed

the population, people want parliament to make communication easier to

understand, through simplifying the language, condensing the message and

using visual images. Even though this report deals with how parliament should

communicate, much of this can be translated into how the population believe

politicians should communicate. From this, one can thus assume that the way

in which posts are presented matter for whether the posts are read by

constituents or not. This category will therefore look at aspects such as the

language used in the posts, length of the posts, and the use of visuals to

supplements the text.

Measurement

‘Constituency Focus’, ‘Activities in Parliament’, ‘Political Views’ and

‘Accessibility’ is measured as a proportion of the frequency of posts. The issue

with this measurement is that an MP who posts few posts exclusively about

one topic will score high on this. I have attempted to solve this in the data

analysis by controlling for frequency. ‘Focus on all Constituents’ is measured

by the total number of such posts as a proportion of the number of posts

focused at the constituents. This highlights how partisan MPs are in their

communication with their local constituents. Online Responsiveness and

Personalisation are measured in an ‘either or’ way. MPs who engage in two-

way communication or who are personal are given the value of 1, while those

who are not are given the value 0. All the categories are in this was given a

standardised value between 0 and 1.

18

4. Data Analysis

Who uses Facebook?

A total of 433, or two thirds, of MPs have had an active Facebook page since

September 2015. There are slightly more female MPs who use Facebook

(73%), than male (64%). Young MPs are more likely to have an active

Facebook page than older MPs; all MPs under 30 and 87% between 31 and 40

have active Facebook pages, while only 47% of 61-70 and 27% over 70 have

the same. On a party basis one can see that the 66% of Conservative and 60%

of Labour MPs have active Facebook pages. As for the other parties, one can

see that all of SNP and Plaid Cymru MPs have Facebook, the previous

pioneering party in terms of Internet communication, the Liberal Democrats,

have 63% of their MPs with active Facebook pages, while all the other parties

average 61%. Scottish MPs are therefore the overall most active on Facebook

with 97% active users, while Irish MPs are the least active with only 53%

using Facebook. MPs in more marginal seats are more likely to have Facebook

with 87% of those MPs with less than a 5% majority and 76% of those MPs

with a less than 10% majority having one, while only 57% of those between 40

and 50% and 48% of those with over 50% majorities having one. There are

large differences between the different cohorts, among MPs elected in 2015 a

total of 91% have an active Facebook page, while among MPs elected before

2005 under 50 % of MPs in the different cohorts have Facebook pages with

percentages as low as 26% for the 1983 cohort.

19

Among those who use Facebook, the average number of posts within the 31

days period is 17.6 posts. There is however high variance, from 0 posts to 113

posts.

Variables of Facebook Use

How MPs use Facebook is measured in 7 variables: Constituency Focus, Focus

on All Constituents, Activities in Parliament, Political Views, Online

Responsiveness, Personalisation and Accessibility.

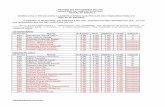

Table 1: Means for the Index VariablesMean Std. Dev.

Constituency Focus 0.5757 0.3165Focus on all Constituents 0.8145 0.3345Activities in Parliament 0.1470 0.1929Political Views 0.2819 0.2541Online Responsiveness 0.2864 0.4526Personalisation 0.5081 0.5001Accessibility 0.6907 0.3425Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

The mean score on the different variables shows six initial findings. Firstly, it

is evident that Facebook is used to a great extent to communicate with

constituents. Almost 60% of all posts in the study are focused on constituents,

making constituency focus the main mode of communication on Facebook.

Secondly, MPs tend to focus on the whole constituency, and are not partisan in

their communication. They are thus not just directing their Facebook

communication to the local party elites, as some of the representation literature

suggested. Thirdly, it can be seen that the MPs focus relatively little on

activities in parliament, or to a certain degree also political views, in their

communication, suggesting that Facebook is not primarily used for

communication of political views and activities. A fourth observation is that

20

about 50% of MPs choose to be personal on Facebook. This is a substantial

amount, but perhaps not as many as could be expected based on previous

research that has highlighted the personal aspect of social media. Another

observation is that the number of accessible posts is almost at 70%, suggesting

that MPs who are using Facebook are using it in a recipient-friendly way,

making their information easily accessible. Finally, it can be seen that 28% of

the MPs that use Facebook engage in some degree of two-way communication

with voters, a relatively high number compared to what has been found in

previous studies.

Table 2: Factor Analysis, Varimax RotationConstituency Dimension

Political Dimension

Medium Usage Dimension

Const. Focus 0.7910.9400.202-0.1290.0560.1830.463

-0.0880.0830.7760.8500.035-0.0870.188

0.1870.127-0.0350.0570.7970.8060.524

Focus on all Const.Activities in Parl.Pol. ViewsOnline Respons.PersonalisationAccessibilityOnly candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

As there is no obvious reason to assume that these variables are correlated, an

explanatory factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted to unveil

whether the variables establish one, unified, constituency index or whether they

load in different ways. The factor analysis revealed a three-factor solution,

which establishes three separate dimensions of Facebook usage amongst MPs.

Constituency Focus and Focus on All Constituents establish one dimension of

Facebook usage, the Constituency Dimension, which describes the focus on

21

constituents in Facebook communication4. Activities in Parliament and

Political Views establish a second dimension, the Political Dimension, where

the focus is on communicating political activities and views. Finally, Online

Responsiveness, Personalisation and Accessibility establishes a final dimension

that describes how MPs use the medium Facebook rather than the content of

their posts, named the Medium Usage Dimension.

The Constituency Dimension

The dataset consequently reveals that one way MPs use Facebook is to focus

on the constituency. The MPs who use Facebook in this way direct their posts

at their constituents, and they do to a large degree address all constituents when

they do. The factor analysis also shows that MPs who use Facebook in this way

tend to focus less on political views. This way of using Facebook corresponds

with the ‘specific’, constituency, model of representation. This manner of using

Facebook implies that the constituents are the primary focus of communication

and that this communication is essentially party neutral. The MP is not

promoting the party, but rather promoting themselves and their constituency

work.

This section will analyse the different characteristics of MPs who use

Facebook to communicate with constituents.

Age

4 Accessibility also loads on this dimension. For simplicity, I have decided to chose to include accessibility in the factor dimension with the strongest loading and thus chosen to define loading as over 0.5. It can however, be argued that accessibility establish its own, separate dimension. But as it aligns well with the Medium Usage Dimension, I have chosen to incorporate it into this.

22

Age is negatively correlated with the Constituency Index (Peasons R -0.126,

sig. 0.008). Suggesting that younger MPs are slightly more likely to use

Facebook to communicate with constituents than older MPs are.

Party

There are some differences in the how MPs from different parties use

Facebook, as illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3: Means for the Constituency Index by PartyConstituency Focus Focus on all Constituents Constituency IndexMean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.

Cons 0.639 0.326 0.850 0.332 1.490 0.602Lab 0.507 0.315 0.747 0.364 1.254 0.612SNP 0.466 0.183 0.834 0.247 1.300 0.340Other Party 0.638 0.342 0.828 0.314 1.390 0.553Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

Conservative MPs score overall the highest on the Constituency Index and on

both the Constituency Focus and the Focus on all Constituents variables.

Labour MPs score the lowest overall, and focus the least on constituents in

their posts. When there is a constituency focus they tend to focus more on

Labour supporters within their constituency, rather than all constituents. The

possible reasons for this difference will be looked at in more detail under the

Political Dimension section. SNP MPs are shown to focus less on the

constituency in their posts than both the Conservatives and Labour. This is

most likely because the SNP MPs tend to focus on the whole of Scotland in

their communication rather than just their specific constituency. When SNP

MPs focus on their constituency they do however focus on all of their

constituents almost to the same degree as Conservative MPs. This places them

between Labour and the Conservatives on the overall scale.

23

Years in Office

The number of years an MP has in office is negatively correlated with the

Constituency Index (Pearson’s R -0.214, sig. 0.000). An MP with fewer years

in office is therefore more likely to focus on their constituency in their posts.

This can be seen when looking at the means for the different parliamentary

intakes, where the 2010 and 2015 cohorts score the highest, while MPs elected

in the 1980s and to a certain extent the 1990s and early 2000s5 score relatively

low. Norton and Wood (1990) argue that each new cohort of MPs is motivated

to build up a personal vote. Using Facebook to do this might, for the new 2010

and 2015 cohorts, be a natural way to do this, explaining why they tend to

focus more on the constituency than their more long-serving counterparts.

Majority

There is a small negative correlation between majority and the constituency

index (Pearson’s R -0.13, sig. 0.007), suggesting that the MPs in more

marginal seats are more likely to focus on the constituency in their Facebook

posts than those with a high majority. This can be seen clearly when in Table 4.

Table 4: Means for the Constituency Index by MajorityConstituency Focus Focus on all Constituents Constituency IndexMean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.

0-4.99 0.692 0.283 0.873 0.278 1.565 0.5175-5.99 0.616 0.318 0.801 0.332 1.417 0.57910-19.99 0.584 0.302 0.823 0.327 1.407 0.57220-29.99 0.546 0.305 0.866 0.304 1.412 0.52430-39.99 0.530 0.310 0.767 0.350 1.297 0.59740-49.99 0.538 0.354 0.797 0.386 1.334 0.683Over 50 0.409 0.392 0.624 0.447 1.033 0.795Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

5 With the interesting exception of the 1997 cohort that score quite high

24

These findings are consistent with some previous findings suggesting that more

marginal MPs are more likely to use the constituency service model (Jackson

and Lilleker 2009). This is likely to be because MPs in more marginal

constituencies are trying to strengthen their incumbency, their position locally,

to be re-elected, and that connecting with constituents, and especially all

constituents in a non partisan way, is a way to achieve this. Studies on the

constituency role and marginality have previously shown that MPs in safe seats

are just as likely to be diligent constituency MPs as their more marginal

counterparts (Norris 1997). It may therefore be the case that the MPs in more

marginal seats merely put more focus on communicating their constituency

service than MPs in safer seats.

Parliamentary Position

There are also some differences between MPs with different positions.

Table 5: Means for the Constituency Index by Parliamentary PositionConstituency Focus Focus on all Constituents Constituency Index

Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.Cabinet Minister

0.393 0.408 0.508 0.278 0.901 0.890

Shadow Cabinet Minister

0.318 0.300 0.537 0.332 0.855 0.697

Other 0.5926 0.309 0.835 0.327 1.428 0.555Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

When comparing the average scores of ministers, shadow ministers and others,

there is evidence that having a high position within the party leads to lower

scores than a low position. The standard deviation is however much higher

within these high positions, suggesting that there are some ministers and

shadow ministers that focus more on their constituency.

25

Overall

To determine what the impact of these correlations are there was executed a

regression to control for the other variables.

Table 6: The Constituency Index. B-Coefficients, S.E. in parentheses.I II III IV V VI VII

Constant 1.386***(0.035)

1.610***(0.096)

1.428***(0.110)

1.525***(0.115)

1.581***(0.115)

1.042***(0.224)

1.022***(0.227)

Gender 0.013 0.006 0.057 0.057 -0.003 -0.032 0.033

Age -0.068**(0.28)

-0.060**(0.27)

-0.054**(0.27)

-0.002 -0.013 -0.012

PartyCons 0.238***

(0.064)0.238***(0.063)

0.199***(0.063)

0.193***(0.065)

0.198***(0.066)

SNP 0.040 0.029 -0.075 -0.089 -0.098

Others 0.260 0.209 0.230 0.195 0.187

Majority -0.005**(0.002)

-0.004*(0.002)

-0.003 -0.003

Years in Office -0.102***(0.028)

-0.078***(0.028)

-0.078***(0.029)

Parl. PositionShadow Cabinet

0.236 0.229

No Position

0.543***(0.191)

0.537***(0.191)

Frequency 0.001

***p<.01, **p<.05, *p<.10.Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).Dependant Variable: Constituency Index

The significance of majority and age both disappeared when controlling for

numbers of years in office and parliamentary position. The number of years in

office is still significant when controlled for these variables, but the correlation

is very small. However, it cannot be ruled out that majority and age also

matter, as they appear to be related to numbers of years in office.

There is also a sizable impact of having no position within the parliament

compared to being in the cabinet. There is on the other hand no significant

impact of being a part of the shadow cabinet compared to the cabinet; this

26

means essentially the same for constituency work. The difference is therefore

about whether the MP has a high or low position in the party, rather than being

a part of the Government or not, on how much focus they put on the

constituency.

The regression finally confirms that there is a significant difference between

Labour and the Conservatives when controlling for other variables. It is

therefore likely that there is something specific about the parties or the parties’

position that makes their member MPs focus more or less on the constituency

in their communication, which will be evaluated later.

The Political Dimension

Posting information about political views and activities in parliament on

Facebook establishes a separate usage dimension. The factor analysis shows

that MPs who have a high percentage of posts with Political Views and

Activities in Parliament, tend to focus fewer posts on the constituency. Even

though reporting on activities in parliament and explaining political views

arguably can be a part of the constituency representation, it appears as though

those who posts a lot about this tend to focus less on the constituency. This

way of using Facebook therefore corresponds more with the ‘general’, partisan,

model of representation. Previous research has highlighted how high focus on

activities in parliament and political views tend to correspond with a party-

centred focus of communication, as this communication tends to be focused on

promoting the views of the party rather than constituency service (Williamson

2009, p.516; Zittel 2003). The factor analysis also shows that MPs who use

27

Facebook in a political manner are less personal on Facebook. This

corresponds with the view that focusing on policy is an alternative to focusing

on personality (Jackson and Lilleker 2009, p.259), which again corresponds

with the party model of representation, as these MPs appears to be focusing

less on promoting themselves and more on promoting the party (Jackson and

Lilleker 2011).

This section will analyse the different characteristics of MPs who use

Facebook to communicate political views and activities in parliament.

Party

There are again some party differences on the political index as illustrated in

Table 7.

Table 7: Means for the Political Index by PartyActivities in parliament Political Views Political IndexMean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.

Cons 0.126 0.187 0.230 0.254 0.355 0.368Lab 0.179 0.222 0.348 0.265 0.526 0.225SNP 0.171 0.132 0.320 0.137 0.491 0.381Other Party 0.105 0.148 0.304 0.303 0.409 0.368Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

The Labour MPs focus to a greater degree on activities in parliament and

political views than other MPs. The reason why Labour MPs focus on political

views and activities in parliament, and less on the constituency as seen

previously, while the Conservative MPs focus more on the constituency and

less on political issues can be explained by differences in how the parties view

their role as representatives. Rush (2001) asked MPs what the most important

thing was when carrying out the role as a representative: the nation as a whole,

28

the party or the constituency. Overall, MPs tended to prioritise the constituency

highest. However, Labour MPs were found to more frequently prioritise the

party than other MPs did. There might therefore be a factor specifically related

to the Labour party that makes them focus more on the party, most likely

connected to the party’s history as a party born out of a social movement.

Another possible explanation is that this reflects a difference between being a

member of the governing party and being a member of the opposition. It might

be that Labour MPs are more reliant on promoting their party and its policies as

a part of the permanent campaigning, while the Conservatives who are in

government is not. Many of the Labour party MPs post with a political

message are also attacking the government’s policies, which is a type of post

that Conservative MPs won’t usually make. This gives Conservative MPs more

of an opportunity to focus on the constituency in a nonpartisan way. This

explanation is however speculative, and further research must be done to

validate this.

Parliamentary Position

There are differences between the MPs’ parliamentary position and how much

they focus on political views and activities in parliament as shown in Table 8.

Table 8: Means for the Political Index by Parliamentary PositionAct. in parliament Political Views Political IndexMean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.

Cabinet Minister 0.000 0.000 0.215 0.262 0.215 0.262Shadow Cabinet Minister

0.130 0.233 0.396 0.330 0.526 0.459

Other 0.151 0.192 0.278 0.249 0.429 0.364Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

29

A comparison between the different means reveals that it is in fact the Cabinet

Ministers that focus the least on activities in parliament and political views,

while shadow ministers’ focus the most. This is most likely explained by the

fact that shadow ministers’ responsibility is to show the population that Labour

can do a better job on their assigned area, thus making it natural for these MPs

to post frequently about political issues to convince the people that Labour

have the better policies. Another explanation is that Cabinet ministers focus

very little on the political dimension, especially activities in parliament, in their

posts, therefore making them diverge from everyone else. These explanations

are however just suggestions, and further interviews with the MPs would

probably reveal more of the rationale behind the different choices.

Overall

Table 9: The Political Index. B-Coefficients, S.E. in parentheses.I II III IV V VI VII

Constant 0.434***(0.022)

0.438***(0.061)

0.573***(0.061)

0.536***(0.073)

0.553***(0.074)

0.423***(0.146)

0.475***(0.146)

Gender -0.004 -0.005 -0.043 -0.043 -0.060 -0.059 -0.062

Age -0.001 -0.008 -0.010 0.006 0.004 0.002

PartyCons -0.183***

(0.040)-0.183***(0.040)

-0.194***(0.041)

-0.182***(0.042)

0.195***(0.042)

SNP -0.043 -0.039 -0.069 -0.061 -0.037

Others -0.014 0.005 0.011 0.018 0.038

Majority 0.002 0.002*(0.001)

0.002*(0.001)

0.002*(0.001)

Years in Office -0.029 -0.028 -0.030

Parl. PositionShadow Cabinet

0.175 0.193

No Position

0.125 0.142

Frequency -0.003*** (0.001)

***p<.01, **p<.05, *p<.10.Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

30

Dependant Variable: Political Index

When controlling for the other variables, the only significant variable

(excluding the weak frequency correlation) is being a Conservative MP in

comparison to being a Labour MP. SNP is not significantly different from

Labour, and are thus likely to diverge from Conservatives in a similar way to

Labour.

There is also a minor effect of majority when controlled for years in office. It

could therefore be claimed that the MPs who have a large majority are slightly

more likely to focus on political issues. However, as the correlation is very

small and the standard error relatively high, there can there be drawn no real

conclusions based on this.

As for the MPs parliamentary position, it can be seen that despite of the means

when controlled for other variables the effect of being a shadow cabinet

minister compared to a cabinet minister is insignificant. This is most likely

because shadow cabinet ministers are Labour MPs, while cabinet ministers are

Conservative MPs, making much of the difference being explained by party.

However, as the data is the whole population of MPs and not a sample, there

might be reason to claim that as the B-Coefficients for being a shadow cabinet

minister and having no position compared to being a cabinet minister are

relatively large, that there is some kind of relationship between the two, with a

note that the variance is large.

The Medium Usage Dimension

31

The last dimension contains the categories of Personalisation, Responsiveness

and Accessibility. These categories all deal with how Facebook is used as a

social medium, whether the possibilities that lie within the medium are used,

rather than the manner of representation in itself. As for Responsiveness, most

of the MPs who score highly on this score because they respond to comments

left on their posts. However, some MPs are developing further the concept of

responsiveness online. For example, Drew Hendry SNP MP for Inverness,

Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey holds Q&A sessions on his Facebook page

where he invites constituents to raise any concerns they have by leaving posts.

Paul Maskey Sinn Fein MP for West Belfast has introduced an ‘Online

Constituency Service’ by inviting constituents to contact him on Facebook and

Twitter at particular times, opening for confidentiality by sending

personal/direct messages on Twitter and Facebook. And Ben Howlett,

Conservative MP for Bath, advertises on his Facebook page his ‘Howlett’s

Hour’ on Twitter, where he answers constituents questions about particular

topics. Other MPs ask for their constituents’ opinions about what to ask in

parliament or introduce surveys to find their constituents’ views on specific

issues. How personal an MP is on Facebook also varies, it can be the absolute

minimum or it can very personal, as is outlined in the Appendix.

This section will analyse the different characteristics of MPs who use

Facebook in these ways.

32

Age

There is a negative correlation between age and the Medium Usage Index, on

all of the variables separately and overall (Pearson R = -0.265, sig. 0.000).

Table 10: Means for the Medium Usage Index by AgeOnline Respons. Personalisation Accessibility Medium IndexMean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.

Under 30 0.615 0.506 0.923 0.277 0.785 0.238 2.323 0.72931-40 0.388 0.490 0.624 0.487 0.771 0.277 1.783 0.90841-50 0.317 0.467 0.531 0.501 0.711 0.341 1.559 1.00951-60 0.190 0.394 0.405 0.493 0.628 0.365 1.223 0.93761-70 0.182 0.390 0.386 0.493 0.645 0.366 1.213 0.924Over 70 0.000 0.000 0.333 0.516 0.403 0.455 0.736 0.923Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

The means for the age groups show this tendency very clearly. The younger

MPs score consistently higher on all the separate dimensions than do their

older colleagues. Particularly striking is that among the under 30s more than

50% use Facebook for two-way communication, while among the over 70s

none of them do. These differences between young and old MPs is broadly in

line with the technological competence among the population, where the

younger generations are much more used to using such technology and are thus

better as using it to its full extent.

Party

There are some party differences on how MPs communicate with their

constituents.

Table 11: Means for the Medium Usage Index by PartyOnline Respons. Personalisation Accessibility Medium IndexMean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.

Cons 0.286 0.453 0.536 0.277 0.710 0.350 1.533 1.000Lab 0.169 0.375 0.445 0.487 0.648 0.361 1.261 0.902SNP 0.593 0.496 0.648 0.501 0.695 0.269 1.936 1.056

33

Other Party

0.273 0.456 0.273 0.493 0.753 0.302 1.300 0.819

Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

The SNP MPs score much higher than MPs from other parties on the Medium

Usage Index, which is a result of their high scores on online responsiveness

and personalisation. SNP MPs respond to messages and posts on Facebook to a

much greater extent than any other party group, with more than half of the SNP

MPs scoring 1 on Responsiveness. One explanation is that the SNP use social

media as their primary online channel to communicate with constituents. The

SNP is the party where the fewest MPs have personal websites, with only 61%

of SNP MPs having a personal website compared to Labour (93%) and

Conservatives (95%).

Labour performs the worst in this category. One explanation for this is that

Labour MPs are the ones that use Facebook in a political way and that the

political dimension users score the lowest on the medium usage variables. This

can be explained by either the fact that many MPs with high scores on political

views tend to post directly from Twitter to Facebook, or that posts reporting on

parliament or political views tend to become more technical and less accessible

for the population as a whole.

Years in Office

There is a negative correlation between an MP’s years in office and the

Medium Usage Index (Pearson’s R: -0.314, sig. 0.000). MPs who have been in

office for a shorter time are thus more likely to use the possibilities that lie in

medium, through making posts more accessible, more personal and engaging in

34

two-way communication. This can be an effect of having had to use Facebook

actively in first-time election campaigns, thus being more experienced in using

Facebook as a platform for effective communication. Studies from the United

States have shown that challengers were more likely to be early adopters of

social media than incumbents, suggesting that more recently elected MPs

(elected in 2010 and 2015) might have more experience and competence when

it comes to Facebook usage (Williams and Gulati 2013). Another possible

reason is that MPs who have spent more years in office are more likely to have

established a way to communicate with constituents and partisans before the

emergence of Facebook. They might therefore not put as much effort into using

the platform, and may use it more as an extension of traditional communication

tools rather than for the possibilities of it.

Majority

The majority of the MP is negatively correlated with the Medium Usage Index

(Pearsons R: -0.113, sig. 0.006). This suggests that MPs in more marginal seats

are slightly more likely to use Facebook for efficient communication. Jackson

and Lilleaker (2009, p. 250) suggested that social media may be a part of the

‘permanent campaign’, and that MPs in more marginal seats therefore focus

more on effective communication. Replying to messages on Facebook and

being personal is a way to be perceived as accessible and trustworthy, which is

often regarded as key for re-election (Fenno 1978). This taps into the

discussion on the ‘personal vote’. Even though the evidence for the personal

vote is mixed (Norris 1997; Norton 2004; Jackson 2008; Lilleker 2006; 2008),

35

this finding suggests that MPs to a certain degree appear to believe in the

personal vote.

Parliamentary Position

The parliamentary position of the MP does again lead to differences in usage.

Table 12: Means for the Medium Usage Index by Parliamentary PositionOnline Respons. Personalisation Accessibility Medium IndexMean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std.

Dev.Cabinet Minister

0.111 0.333 0.222 0.441 0.612 0.380 0.945 0.947

Shadow Cabinet Minister

0.150 0.366 0.250 0.444 0.520 0.414 0.920 0.935

Other 0.297 0.458 0.527 0.500 0.701 0.336 1.525 0.980Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).

The MPs who do not have a high position in the party score higher on the

Medium Usage Index. They score in particular much higher on personalisation,

which is not surprising seeing that MPs with higher positions are even less

likely to have anything to do with the running of their own Facebook page than

other MPs, and because of their high position there is less reason to create an

illusion of them posting personally. They are further on also less responsive to

messages. This can be explained simply by the difference in the number of

Facebook likes, and thus people who engage with their posts, with ministers

having an average of 50113 likes, shadow ministers with 26586 likes and other

MPs with only 7278 likes.

36

Overall

Table 13: The Medium Usage Index. B-Coefficients, S.E. in parentheses.I II III IV V VI VII

Constant 1.478***(0.059)

2.273***(0.160)

1.986***(0.181)

2.127***(0.191)

2.231***(0.190)

1.741***(0.375)

1.531***(0.371)

Gender 0.057 0.033 0.086 0.085 -0.025 -0.003 0.010

Age -0.243***(0.046)

-0.227***(0.045)

-0.218***(0.045)

-0.116**(0.051)

-0.126**(0.051)

-0.116**(0.050)

PartyCons 0.247**

(0.106)0.248**(0.105)

0.177*(0.105)

0.191*(0.109)

0.246**(0.108)

SNP 0.634***(0.152)

0.618***(0.152)

0.427***(0.156)

0.430***(0.158)

0.331**(0.157)

Others 0.256 0.183 0.221 0.211 0.126

Majority -0.007**(0.003)

-0.005 -0.004 -0.004

Years in Office -0.187***(0.046)

-0.172***(0.048)

-0.164***(0.047)

Parl. PositionShadow Cabinet

0.385 0.310

No Position

0.486 0.415

Frequency 0.011*** (0.003)

***p<.01, **p<.05, *p<.10.Only candidates with an active Facebook page are included in the analysis (N=424).Dependant Variable: Medium Usage

The regression reveals that when controlling for the other variables there is still

an effect of age, but the effect becomes considerably lower when controlled for

years in office. The effect of the number of years in office also becomes much

lower when controlled for age, but it remains highly significant. The effect of

majority becomes insignificant when controlling for these variables. This again

confirms that these three variables are related, and thus perhaps all feeding into

decisions for Facebook usage. Interestingly, even though majority overall

becomes insignificant when controlled for age and years in office; there is still

an effect of majority on just online responsiveness (Pearson’s R -0.003, sig.

0.05). There is therefore some evidence suggesting that MPs with a smaller

37

majority are more likely to respond to messages and posts on Facebook, though

the correlation is very small.

The effect of being an SNP MP is significantly reduced when it is controlled

for years in office and some for frequency of posts. This suggests that some of

the effect of the SNP derives from the fact that they are more recently elected

and post slightly more often than other MPs. However, the effect of the SNP in

comparison with the Labour party is still sizable, but much closer to that of the

Conservatives. It can thus be concluded that both Conservative and SNP MPs,

utilise the possibilities for Facebook as a medium and communicate efficiently

in comparison to Labour MPs.

The significance of not having any position in relation to being a minister is

sizeable. The effect is however not statistically significant, which suggests that

there is some variance. However, as previously noted, this is an entire

population, which means that it can be concluded that there is some

relationship between the two.

38

5. Discussion and Conclusion

The analysis of the data shows that what Jackson and Lilleker (2009, p.257)

called a ‘small minority of pioneers’ appears to have become a much larger

group. A majority of MPs are now actively using Facebook between elections,

suggesting that Facebook usage for representation is becoming the norm rather

than the exception. This is true especially for the MPs of the more recent

intakes, making it likely that the parliament will get increasingly active on

Facebook as new MPs replace the old.

It is, however, not just the fact that MPs use Facebook, but the way they use

Facebook that is interesting. This dissertation has on a general level found that

MPs’ focus is primarily on their constituents, and that this focus tends to be

non-partisan. There are some differences between groups of MPs: Younger,

more recently elected MPs score slightly higher in terms of constituency focus,

there is some evidence pointing toward MPs in more marginal seats focusing

more on the constituents, and the MPs without cabinet and shadow cabinet

positions focus to a sizable degree more on their constituency than do their

cabinet and shadow cabinet colleagues. There is also a visible party effect

where Conservative MPs focus much more on constituents than their Labour

counterparts, who appear to focus more on the party and political views.

However, despite these differences, the proportion of MPs that focus on the

constituency overall is much larger than that who focus on political issues and

the party, making it evident that Facebook is to a great extent used as an

extension of the constituency service dimension of being a representative.

39

This finding replicates much of what has been found in previous studies of

MPs online activities, suggesting that Facebook works like the online sphere in

general: MPs focus on their constituents. Previous studies, like Norton (2007),

do however conclude that the constituency focus on Facebook is an attempt to

bolster the party in the system. There can however not be made any such

conclusions in this dissertation. The dissertation would have benefitted from a

more inclusive index that also measured variables such as general party focus

(not constituency level), and more variables describing the content of the posts,

as this would arguably have made it possible to give a firm conclusion on this.

However, the fact that the posts tend to be non-partisan, often personal and not

focus on political views is highly suggestive in the direction that Facebook is

not necessarily used to bolster the party, but rather to bolster the individual

MP.

Despite this dissertation replicating findings on a primarily constituency

focused way of communicating, there is some evidence suggesting that the way

in which this communication between MPs and constituents take place might

be changing. Previous studies have found that MPs use the internet as an

extension of the traditional way to represent, to disseminate large amounts of

information to, rather than engaging with, their constituents (Norton 2007;

Jackson 2003; Jackson and Lilleker 2009). This study has shown that a

substantial amount of MPs, 28.6%, use Facebook for two-way communication

with their constituents. Even though this does not constitute a majority, it

implies that there is a certain level of two-way communication between MPs

and constituents on Facebook that has not been found in previous studies.

40

Because of this change from previous studies, it can therefore be suggested that

MPs increasingly use the internet, and specifically Facebook, to engage with

constituents beyond the traditional fashion. As the data also shows that it is the

younger and more recently elected MPs who are more likely to be responsive

on Facebook, it can be reasonable to assume that with the intake of new,

younger MPs, there might be increased levels of engagement with constituents

on Facebook. As this dissertation has seen, there are some MPs who innovate

in ways to use social media for two-way communication6. With this innovation

it might be possible that there will be a diffusion of these techniques, in the

same way there has been diffusion in the use of websites and social media

(Norton 2007; Willamson 2009; Jackson and Lilleker 2009), to further expand

this way of utilising Facebook. It is possible that there could be some sort of

critical mass effect, where when a large enough number uses two-way

communication online and e-representation techniques, it might be adopted by

more MPs and become the norm rather than the exception. However, this will

depend on whether MPs see the usefulness of such usage. Interviews with MPs

would have helped to nuance these predictions, as it would have helped to

better understand the reasoning behind MPs’ online choices.

Despite the difficulty in saying anything with certainty, this study has

suggested that there are possibilities within Facebook for expanding the way

representation works. If the tendency of constituency focus and online

responsiveness continues, Facebook might alter the possibilities for

representative democracy. In a time of distrust and disengagement, and where 6 Examples in chapter 3 and appendix

41

people are no longer active in political parties, there has been highlighted a

need to find new, alternative ways to increase participation and strengthen the

representational link between people and parliament. The internet has been put

forward as a possible channel for this (Lusoli et al. 2006; Witschge 2004). The

Digital Democracy report (2015) has found that the people want to be able to

communicate with parliament online, suggesting that from the side of the

people, communication with their MPs on Facebook establish a possible

solution. Through Facebook, MPs can inform constituents about their

activities, views and other relevant information, and constituents can comment

on this and discuss issues, both with the MP and other constituents. Facebook

therefore represents the possibility of establishing a direct link from the MP to

all constituents that can enhance representation.

However, for Facebook to become a truly effective platform for representation,

MPs will have to continue to expand their two-way communication and make

sure their posts are accessible to a public wider than those who voted for the

winning party. On the constituency side, there must also be made changes in

the way the population perceive MPs on Facebook. Studies have found that it is

only the most politically active that follow MPs on Facebook and that

politicians tend to reach their own supporters, thus meaning that politicians’

communication on social media is to a great extent preaching to the converted

(Norris 2006, also Norris and Curtice 2008; Karlsen 2015; Lusoli et al. 2006).

For expanded representation on Facebook to work, MPs’ Facebook pages must

become Liked by not just the most politically active and their strong

supporters, but by the wider population of the constituency.

42

Despite the possibility for an expansion of online representation, there are

some clear limits. It is firstly unlikely that there will be a great change in how

the population use Facebook. Even though MPs might increasingly use

Facebook in ways that could open for more contact, it is unlikely that they will

reach all people in their constituency with this limited type of contact therefore

making the communication less representative. It is secondly very probable

that the quality of the contact through social media is poorer than face-to-face

contact. There is therefore a quantity versus quality question that must be

answered, to evaluate whether there is reason expand the use of Facebook.

Further studies might look into who follows MPs on Facebook and how the

population perceive MPs’ Facebook pages. This would shed some light on

what the people want from their representatives, and also whether there is any

reason for MPs to keep expanding their representational activities on

Facebook.

This dissertation has shown that Facebook is used, and has the potential to be

used even further, as a way in which MPs can strengthen their individual

position independently from the party by communicating directly with their

constituents. There are differences between how different groups of MPs

communicate on Facebook, based on party, intake, age and position in

parliament, but there can be witnessed a general constituency focus in their use.

Facebook consequently has the potential to strengthen the constituency

representational link in a time of party decline and decreased trust. However, it

is unlikely that Facebook can change representation completely, both because

43

of issues on the side of the MP and on the side of the constituents. On the other

hand, it may have the potential to add an extra dimension that expands the

representative basis of the British parliament. It might be a way in which

certain groups of the population can feel closer to their local MP, and feel as

though politics is becoming more about the people again.

44

Appendix: Code Book

Every individual post an MP posted is given either 0 or 1 in the different

categories.

Frequency

All posts from 29th of January to 29th of February are counted, except from

change of the page’s profile or cover photo.

Constituency Focus

Constituency Focus is measured by the number of posts that are directed at the

constituency. Every post of the individual MPs are analysed to recognise where

the focus of each posts is, and the posts with a clear constituency focus are

given 1 for Constituency Focus.

Posts about the MPs’ activities in the constituency

One type of post that is counted as a post focused on the constituency is a post

that reports on the constituency and the MPs’ activities in it.

Suella Fernandes, Conservative MP for Fareham post constitutes an example of

a post directed at constituents:

“Some delicious fair trade chocolate tasting (and dried fruits for me) to mark FairTrade in Fareham. Good to support this with Mayor and Mayoress Ford and Cllr Sean Woodward. Well done to Rachel Hicks and the walking, talking banana!”Post given 1 on Constituency Focus

45

Information about local issues and events

Another type of post that is coded as focused on the constituency is reports of

information about what is happening in the constituency. This can either be

practical information, such as Gordon Henderson, Conservative MP for

Sittingbounrne and Sheppey post abut roadwork:

”A249 Update - 4th February 2016. Good news! Please find below the press release I have just received from Highways England: A249 near Sittingbourne to reopen tomorrow. Both lanes on the northbound A249 are expected to reopen tomorrow morning (Friday 5 February) following the completion of work to repair damage caused by a burst water main last month”.

Or it can be about upcoming events that constituents might be interested in.

Such as Sarah Newton’s, Conservative MP for Truro and Falmouth, post about

a local event in Truro saying:

”Do come along and join me for this great local event and support Shelterbox”

and linking to a page with information about the event.

Post given 1 on Constituency Focus

MPs congratulating a constituent

Another example of an MP that directs itself at constituents is when an MP

takes time to congratulate a local constituent. Such as Richard Arkless, SNP

MP for Dumfries and Galloway’s post about a local constituents involvement

in Sport Relief 2016 saying “Well done Lindsey!” and linking to an newspaper

article on what she is doing.

Post given 1 on Constituency Focus

46

Posts about surgeries or other meetings

A very common type of post that counts as a post directed at constituents is

about local meet-ups or surgeries in the constituency. In these posts the MP is

directing the post at constituents and asking them to meet. Examples includes

Tim Farron, Liberal Democrat MP for Westmorland and Lonsdale post about a

open meeting was having:

”If there's any issue I can help you with and you're able to get to Windermere tomorrow afternoon, please come along to the Marchesi Centre between 4 o'clock and 5 o'clock and I'll do my best to help.”

Or, Stephen Kinnock Labour MP for Aberavon’s post saying:

“I will be holding my next advice surgery in Briton Ferry Community Centre on Friday 4th March between 5.30 and 6.30pm“. Post given 1 on Constituency Focus

Posts about MPs activities who are being related to the constituency

Other examples of posts directed at constituents can be about activities of the

MP that is not directly related to the MPs constituency work, but the MP still

addresses his or hers local constituents. Example of this includes Michael

Dugher Labour MP for Barnsley East’s post about his meeting in parliament

with the Alzheimer society, reporting that:

“(…) Barnsley Hospital is outperforming the national average length of stay for dementia patients, which is very important for making treatment less frightening and confusing. Barnsley Hospital and charities like BIADS, of which I am proud to be a patron, do fantastic work caring for individuals and families who are impacted by dementia and it is welcome news that our local health services are helping to fix dementia care.”Post given 1 on Constituency Focus

47

Posts about MPs activities in parliament being directed at the constituency

Some MPs also addresses their activities in parliament to their constituents by

making it relevant for their constituents. An example of this is Tim Loughton,

Conservative MP for East Worthing and Shoreham’s post about his speech in a

Westminster Hall debate on the performance of Southern (Govia Thameslink

Railway) attaching a video and writing:

“(…) I brought up how I had received an email just that morning from a constituent saying that they had just been told that the 7.31 am from Shoreham-by-Sea had been cancelled. At 7.35 am, they saw it shoot through Shoreham station. Later in the day, I found out that, in fact, the train had not been cancelled(…)”. Post given 1 on Constituency Focus

Posts about something relevant to the constituency

Finally, if a post does not mention the constituency explicitly, but something

that is otherwise related to the constituency, and almost exclusively the

constituency, it is also classified as focused on the constituents. For instance,

Stephen Doughty, Labour MP for Cardiff South and Penarth, post about the

local asylum centre Lynx house does not explicitly mention the constituency,

but is clearly aimed at constituents:

”Excellent write up of the latest revelations in the Clearsprings asylum controversy being pursued by me and Jo Stevens. CEO was forced to apologise today to Home Affairs Committee for red bands scandal + extraordinary revelations about how their Chair was paid £960k last year and the CEO £200k+ after my research into company records. Tomorrow I have secured a Commons debate to question Home Office Minister on what they knew and how these contracts are being monitored - huge questions about whether they are doing right by either the vulnerable people fleeing persecution or the communities they live in”.

Post given 1 on Constituency Focus

48

Posts with no special constituency focus

Any post that does not mention the constituency or direct itself at the

constituency in any explicit way is not regarded as focused on constituency.

This can either be posts directed at all partisans or the whole nation.

Post given 0 on Constituency Focus

Posts about a whole region

However, a post that focuses on something that is of the interests of a whole

region (eg. Scotland, Cornwall, London) does not count as a post directed at

the constituency. For instance Scott Mann, Conservative MP for North

Cornwall posted:

“Delighted to join Cornwall colleagues to welcome bouquets of magnolias to 10, Downing Street to mark the early arrival of spring to Cornwall (…) This is the fifth year spring has been declared in this way for Cornwall and the first time a bouquet has been presented to Downing Street to mark the occasion.”

This clearly relates to Cornwall, but not his constituency of North Cornwall

directly, and is thus not included in constituency focus.

Post given 0 on Constituency Focus

Focus on all Voters in the Constituency

Focus on all Voters in the Constituency is measured by the number of posts

that directs itself at all constituents without excluding any groups. Every post

directed at all people in the constituency, thus without any partisan slant, is

given 1 on Focus on all Voters in the Constituency.

49

Campaigning posts