magazine spread fadn203

-

Upload

natasha-cirisano -

Category

Documents

-

view

226 -

download

0

description

Transcript of magazine spread fadn203

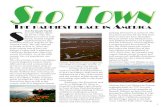

THE CULT OF N E O N

F r o m g r u n g y p u n k r o c k m u s i c c l u b s t o U l t r a M u s i c F e s t i v a l : t h e s t o r y o f h o w M i a m i ’s l o c a l c o l o r

b e c a m e t h e c o l o r s o f a g e n e r a t i o n .

LOCAL COLOR

We love our mu-sic, we love our culture and we love Ultra Music Festival. We have seen the light,

and it is neon.

Ultra?” The lady at the Party City counter asked as she rang up our glow sticks.

It was a bright Miami morning in spring 2011, the day before Ultra Music Festival, and I was standing with my sister at the checkout line. In other words, we were nearly t-minus twenty four hours away from Friday afternoon, when the entire city stops in an international celebration of electronic music and all manner of the loud, sleek, metallic, fluorescent and the glowing. “Is it that obvious?” I laughed, taking my purchase. Yes, yes it was. Ultra Weekend might as well be a national holiday if you live in Miami. School trips have been can-celled because of it as if it is a religious obligation. And it kind of is. All roads lead to Ultra: it’s where pilgrimages are made and legends are born. The music festival experience is a right of passage, and an affirmative answer to the ubiquitous, “Are you going to Ultra?” is received with the same enthusiasm as finding some long lost twin. It wouldn’t be too off to say that your first Ultra experience is practically a birthright. Nearly year round, Miami stands in a state of suspension for Ultra. In October we rush online to

buy our Early Bird tickets, in December we eagerly await the lineup, in February we raid American Apparel as if we were preparing for a mission to Mars. Finally, in March, two weeks before the event, the tickets arrive at everyone’s doorstep on the same day. One look at Facebook and you would think that everyone had won a fabled trip to the chocolate factory. The shiny holograms are a badge of mastery in one of Miami’s many languages, nothing but the beat. We love our music, we love our culture and we love Ultra Music Festival. We have seen the light, and it is neon.

I learned in my junior high school English class that certain writers ascribe to a genre called local color, meaning that they base their stories off imagery of their own cities and towns – the language, the people, the places. Every town has its own flavor. In Miami, it’s safe to say that neon

is quite literally our local color. My senior year English teacher must have seen it in his students when he put up a poster for national poetry month with a quote by Elizabeth Bishop: “Bright objects hypnotize the mind.” No one escapes Ultra season, and no one escapes the neon. Fast forward a few weeks later and I’m at our neighbor-hood party store spending entirely too much on an arsenal of the light and the luminous en route to Downtown Miami for the biggest weekend of the year. Elizabeth Bishop certainly knew what she was talking about. Bishop was a rager before her time, but pop culture has had a love hate relationship with neon. It’s been said that the fluorescent hues are unnatural, obnoxious, blinding, tacky, avant-garde, and mesmerizing. I’ve heard clothing company CEOs say that “nobody wants to wear a highlighter as a shirt.” But apparently, they do. You might have noticed that now neon is everywhere. Jimmy Choo’s pointed pumps flaunted the fluorescent, Tron built an entire world on a color palette of black, white, incandes-cent blue and orange, and dub-step diety Skrillex took home a Grammy for all the glowstick wavers and candy ravers. Neon has proliferated music, film,

and fashion once again. And it’s about time. At the risk of sound-ing like some washed up hipster desperate to prove that she was

All roads lead to Ultra: it’s where pilgrimages are made and leg-ends are born.

the the first, my early encounter with neon was cerca 2009 when the blindingly bright was still an 80’s fashion faux pas. Relegated to the subculture of skinny jeans and asymetrical haircuts, the pop culture powers that be re-served dayglow hues for the Hot Topic regulars: scene kids on the tail of nineties emo culture out to prove that neon was the new black. Neon marked an insular subculture too far left on the electromagnetic spectrum to reach the rest of the population. I was the only one who wore it to school: thank God I was an avid art student or people might have thought my two-tone converse came from some

Have you tried playing with your ring?Sometimes that calms them down, I find.(Bright objects hypnotize the mind.)Get his attention on anything –anything will do - there, try your ring.

The glitter pleas-es him. You seehe squints his eyes; his lip hangs loose.You were say-ing? - Oh Lord, what’s the use,for now the par-rot’s after meand the monkeys are awake. You see

When dance music reached its tipping point, neon came with it. Every decade has it’s flying colors. Gold, silver, black, white. Think the 1920s – black tie affairs, flapper dresses, glitter, glamor. Red, white, blue, yellow. Think the 1950s – wartime, Rosie the Riveter, propaganda, patrio-tism. In their most recent The Twentieth Century in Color book, printing industry giant Pantone predicted that this decade would go for inter-galactic hues. Those strange effervescent shades of glowing blue, purple, yellow, and white would transfix a generation.

If the cosmic print bathing suit I recently bought is any indication, they were right. We don’t choose our col-ors randomly – they come together in our fashion, our politics, our culture: in our greatest fears, our wildest dreams, and, of course, our music. When I think 2010s, I see glowing computer screens and sprawling metropolises that dot satellite images like thousands of LEDS. I see the ever-present intergalactic Mac desktop wallpaper. I see waves of hundreds of thou-sands of people undulating under strobes and laser lines with the Miami skyline in the background. All around me are displays of backlit digital

brilliance. In other words, I see neon. What came first, the music or the future? I tend to think they both converged on each other at the crossroads of Biscayne and the Main Stage.

Today more popular than ever, there’s noth-ing like Ultra Music

Festival weekend – which isn’t just a Miami thing anymore – when the neon-clad masses flock to the stages like a hun-dred thousand Tron extras. There’s something about neon that lures punk rockers and ragers alike. And now, every-one else. Maybe it’s a human desire to stand out in the crowd. Maybe its the escapist fantasy, to bask in this unnat-ural, alluring, hypnotic light. For whatever reason, people like bright colors. And we’re not alone. Species that see in color tend to devour it like candy - especially the bright and shiny. The satin bower bird collects blue souvenirs to decorate it’s nest; the eurasian magpie is known to steal re-flective things. The angler fish lures is prey with a bright light hanging from its forehead in the depths of the ocean. The pretty colors enrapture us too: we’ve always loved neon, and the future has revealed it.

F ast forward again to Friday under a thick of bass and treble. In the

inky darkness of the warm Mi-ami night, I cracked my glow sticks and watched them light up in my hands. Thousands of people all around me had done the same. Music pound-ed, millions of colors exploded in the night. For better or for worse, we had joined the cult of neon, and now we were all glowing in the dark.

other freakish universe. In the wake of Blink-182’s breakup, the pop punk movement had taken a fall from grace and neon was straggling to bring color to the cheeks of a dying era. The days of ‘the scene’ were going, but another long simmering sound was poised to sell out American Apparel from Miami to Ibiza.

M aybe it was an inev-itable effect of the digital world; maybe

people were just tired of the doom and gloom of what time magazine labelled, “The Decade from Hell.” With the end of the 2000s came a new sound for The Millenium, 2.0. It started with the pop/house hybrid David Guetta, a sensation of translation who brought dance beats to America Top 40. Somewhere something clicked: people heard dance music, and they liked it. More specifically, Americans liked dance music, and they liked it more than our music industry had ever thought they could. Calvin Harris collaborated with Rihanna, Will. I. Am. and Flo Rida jumped the bandwagon, and people started listening to remixes of songs on the radio like Coldplay’s, “Paradise,” or Gotye’s, “Somebody That I Used to Know.” What DJ Benny Benassi used to call a “bastard child of the business” was now a full blown phenom-enon. A little more than a year ago I couldn’t find a single Avicii fan in Los Angeles, and suddenly dance music became a household name.

Miami’s local color is still there, but it’s spreading far

beyond the dance music capital of the United States. People on the opposite coast actually know who Avicii and Wolfgang Gartner are, and they want to listen to them even if there are no words.

What came first, the music or the future? I tend to think they both converged on each other at the crossroads of Biscayne and the Main Stage.

- ElizabEth bishop