wo PE PA POLICY RESEARCH DIVISION - Semantic Scholar...universal primary school completion. The...

Transcript of wo PE PA POLICY RESEARCH DIVISION - Semantic Scholar...universal primary school completion. The...

PAPERSP

OL

IC

Y

RE

SE

AR

CH

D

IV

IS

IO

NwoRKINGPrimary Schooling in sub-Saharan Africa: RecentTrends and Current Challenges

Cynthia B. LloydPaul C. Hewett

2003 No. 176

Cynthia B. Lloyd is Director of Social Science Research and Paul C. Hewett is ResearchAssociate, Policy Research Division, Population Council.

We acknowledge the important contribution of Carol Kaufman, our coauthor on previ-ous work on African education. We are grateful to John Bongaarts and Nelly Stromquistfor comments on an earlier draft. Funding for this study was provided by the U.K. De-partment for International Development, The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation,and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Primary Schooling in sub-Saharan Africa:Recent Trends and Current Challenges

Cynthia B. Lloyd

Paul C. Hewett

This material may not be reproduced without written permission from the authors. For alist of Policy Research Division Working Papers, including those available for down-loading in PDF format, see www.popcouncil.org/publications/wp/prd/rdwplist.html.

Abstract

At the dawn of the twenty-first century we estimate that more than 37 millionyoung adolescents aged 10–14 in sub-Saharan Africa will not complete primaryschool. Our estimates are based on data from nationally representative Demographicand Health Surveys from 26 countries, collectively representing 83 percent of thesub-Saharan youth population. This number is nearly twice the entire population ofchildren aged 10–14 in the United States, virtually all of whom will complete pri-mary school. Reducing the number of uneducated African youth is a primary objec-tive of the United Nations as laid out in the Millennium Development Goal for edu-cation, which sets 2015 as the target year for all children to have completed primaryschool and for boys and girls to have equal access to education at all levels. Achiev-ing this goal will require a level of international resources and commitment not yetseen; it will also require better tools for monitoring educational progress at the coun-try level. UNESCO draws on enrollment data derived from national managementinformation systems to create two complementary indicators for assessing progresstoward universal education: the net primary enrollment ratio and the grade fourcompletion rate. Evaluation of these indicators suggests that they provide, at best, anincomplete and, at worst, a biased picture of levels, trends, and gender differences inschool participation and grade attainment. Data from the DHS present a differentand, arguably, more realistic picture of trends in schooling and current attendanceamong sub-Saharan African youth. Whereas steady growth has occurred in atten-dance and attainment for girls in the last 20 years, educational progress for boys hasbeen stagnant. With the decline in educational disparities between boys and girls,the gap in schooling that remains is between the poorest and the richest households.The gap in schooling delineated by household wealth cannot be monitored evenwith the best management information systems. It can, however, be captured usinghousehold survey data that allow the linking of educational attainment to householdeconomic circumstances. We conclude that current monitoring requirements cannotbe fulfilled without substantial new investments in data collection and evaluation.

The completion of primary schooling represents a bare educational minimum for

today’s sub-Saharan African youth as they look forward to at least 40 years of working

life in a rapidly changing local and global economy. Given the close link between school-

ing levels and adult earnings, their economic future and their ability to participate in and

contribute to the global economy are primarily dependent on a rise in educational attain-

ment. On the basis of the data presented in this paper, we estimate conservatively that at

least 20.8 million or 25 percent of young adolescents aged 10–14 in 2000 have never

attended school (11.5 million girls and 9.3 million boys).

Indeed, the level of educational participation and attainment in sub-Saharan

Africa falls significantly below that of all other regions in the developing world. Fur-

thermore, in many African countries, rates of growth in primary school completion

have flattened out or even declined since the mid to late 1980s. We estimate that for

the year 2000 37.2 million or 45 percent of young adolescents aged 10–14 years in the

region will not complete a primary school education.1 Because a few large countries

dominate the regional average, these estimates mask the results for the worst-per-

forming countries. In many sub-Saharan African countries, less than one-third of ado-

lescents currently complete primary school. Further growth in primary completion

rates is necessary for additional educational gains at the secondary level and beyond.

A continuing policy priority remains, at a minimum, the achievement of universal

primary schooling for girls and boys.

In April 2000 at the World Education Forum in Dakar, Senegal, sub-Saharan Af-

rican governments, along with governments from around the world, recommitted them-

selves to achieving Education for All. However, realizing that the target date of 2000

(agreed to in Jomtien, Thailand in 1990) would not be met, the African representatives

postponed the realization of this commitment until 2015. During the 1990s, only three

African countries came close to achieving Education for All: Malawi, Namibia, and

Uganda. Only Kenya, South Africa, and Zimbabwe had achieved that goal before 1990.2

The international commitment to Education for All was given a further boost in 2001

when the United Nations General Assembly adopted a road map toward implementation

of the U.N. Development Declaration. In its second development goal, the declaration

includes a commitment to the achievement of universal completed primary education

4

and gender equity in schooling (United Nations General Assembly 2001). Following

these international meetings, investments in basic schooling have received heightened

attention from donors, governments, and the media because they are seen as a means of

alleviating poverty and jump-starting development in countries that had been left be-

hind during the 1990s.

The uncertainty surrounding the state of progress toward educational goals may

seem surprising given the recent widespread attention they have received and their uni-

versally agreed importance. International population and health targets have been care-

fully monitored for years by well-funded survey programs, starting with the World Fer-

tility Survey from 1975 to 1984 and continuing with the Demographic and Health Surveys.

Progress toward universal primary school completion has been monitored by UNESCO

using data collected centrally from national ministries (UNESCO 2002). Previous as-

sessments of UNESCO data, however, raised questions about their comparability and

quality (Behrman and Rosenzweig 1994; Lloyd, Kaufman, and Hewett 2000). Ques-

tions of data quality should now take on greater significance given the monitoring re-

quirements built into the UN Millennium Development Goal for education.

As a byproduct of an expanded household questionnaire adopted by the Demo-

graphic and Health Survey (DHS) program in the early 1990s, comparable population-

based data on the educational participation and attainment of household members have

been collected in many developing countries.3 The majority of these DHS surveys have

taken place in sub-Saharan Africa, with 26 countries participating since 1990 (see Table

1).4 Data from these surveys are highly representative of the total population of sub-

Saharan Africa; indeed, based on United Nations estimates, 83 percent of young people

(aged 10–24) living in the region are represented. Sample sizes in the DHS for the 10–

24-year age group range from 4,600 to over 22,000. The median date for these surveys

is 1998 and only three of the 26 were fielded prior to 1995.5 Because population funding

agencies gave less priority to undertaking surveys in low-fertility countries, many Latin

American and Asian countries that were further along in their demographic transitions

were not included in the DHS program. Hence, the DHS coverage of these regions is

less comprehensive.

With so many recent DHS surveys available for sub-Saharan Africa, it is possible

to derive estimates of trends in school participation and attainment over the past 30

5

years. These data tell a story of impressive past progress and daunting current chal-

lenges, set in the context of diverse colonial histories, resource endowments, and popu-

lation growth rates. The data also provide a picture of progress toward the goal of uni-

versal primary school completion—a picture that in some ways differs from that portrayed

by UNESCO indicators.

The purpose of this paper is threefold: (1) to highlight the value of consistent and

comparable population-based data on educational participation and attainment for evalu-

ation, planning, and target setting through comparison of alternative indicators of progress,

(2) to extend our knowledge of current patterns and trends in educational achievement

among youth in sub-Saharan Africa, and (3) to identify major challenges based on an in-

Table 1 Sub-Saharan African countries participating in the DHS since 1990

Year of Sample size of populationCountry most recent DHS aged 10–24

Benin 1996 7,361Burkina Faso 1998–99 10,243Cameroon 1998 8,833Central African Republic 1994–95 8,529Chad 1996–97 11,149Comoros 1996 4,852Côte d’Ivoire 1998–99 4,654Ethiopia 1999 22,769Ghana 1998–99 6,991Guinea 1999 10,097Kenya 1998 13,021Madagascar 1997 11,080Malawi 2000 20,884Mali 2001 19,329Mozambique 1997 14,730Namibia 1992 8,714Niger 1998 11,052Nigeria 1999 11,589Rwanda 2000 16,679Senegal 1992–93 14,200South Africa 1998–00 17,276Tanzania 1999 6,115Togo 1998 14,041Uganda 2000–01 12,742Zambia 1996–97 13,790Zimbabwe 1999 10,374

Source: DHS website.

6

depth exploration of schooling differentials by sex and household wealth. Throughout

the paper, we present results separately for boys and girls in order to focus on the gender

gap in schooling and how it is changing.

INDICATORS OF PROGRESS

As a follow-up to the Millennium Summit of the United Nations General Assembly

in 2000, the Secretary General was asked to provide a road map toward implementation of

the UN Millennium Declaration. This road map, adopted a year later by the General As-

sembly, contained many goals, including ten related to economic development and pov-

erty eradication (United Nations General Assembly 2001). These have entered common

parlance as the “Millennium Development Goals.” The second of these is worded as fol-

lows: “to ensure that, by the year 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls alike, will be

able to complete a full course of primary schooling and that girls and boys will have equal

access to all levels of education” (United Nations General Assembly 2001). Increasing

girls’ education is one of the principal strategies identified in the document for achieving

universal primary school completion. The wording of the Millennium Development Goal

for education is less ambitious than the wording of the Dakar Framework for Action adopted

a year earlier, which called for “free and compulsory primary education of good quality”

(UNESCO 2002). Currently, only 14 of the 26 sub-Saharan African countries covered in

this paper have constitutional guarantees of compulsory schooling and, of these, only nine

guarantee free schooling (see Table 2).

Two indicators have been chosen by the international community to monitor

progress toward the Millennium Development Goal for schooling. These are the net

primary enrollment ratio and the grade four completion rate (UNESCO 2002). The logic

behind these two measures is that a level of achievement of 99 percent for both would

imply that universal completion of primary school, which can run one to three years

beyond grade four, was near at hand.

The net primary enrollment ratio captures, at a particular time, the percent of

children of primary school age who are currently enrolled in primary school.6 A primary

net enrollment ratio of 100 would indicate that all children within the eligible ages are

enrolled. However, in a context in which many children start school late, it is possible

7

for a country to have achieved the goal of primary completion while having a ratio

below 100. This could occur if everyone in a particular cohort completed primary school,

but some began after the normal starting age and therefore completed school beyond the

recommended age.

Furthermore, net primary enrollment ratios are not strictly comparable across coun-

tries because of variations in the length of the primary school cycle. From Table 2 we can

see that, in our sample of 26 countries, two have a primary school cycle of four years, two

have five years, 15 have six years, and seven have a cycle of seven years.7 Countries are

Table 2 Key features of educational systems in sub-Saharan Africa: 2000

Constitutional guarantee Age of Years ofCompulsory Free school entry primary school

Benin x a 6 6Burkina Faso 7 6Cameroon x 6 6Central African Republic 6 6Chad x x 6 6Comoros x 6 6Côte d’Ivoire 6 6Ethiopia 7 4Ghana x x 6 6Guinea x 7 6Kenya x x 6 7Madagascar x x 6 5Malawi x x 6 4Mali x x 7 6Mozambique 6 5Namibia x 6 7Niger 7 6Nigeria x x 6 6Rwanda x x 7 6Senegal 7 6South Africa x x 7 7Tanzania 7 7Togo a a 6 6Uganda a a 6 7Zambia 7 7Zimbabwe a a 6 7

a: “To be progressively introduced.”Sources: UNESCO (2002) and Tomasevski (2001).

8

free to design their own school systems, and international standards have not been estab-

lished for the length of a primary school cycle. Using the millennium goal for primary

schooling, countries with a longer primary cycle are currently judged by a tougher stan-

dard than countries with a shorter cycle. This is because the denominator of the ratio is

customized to the number of years in the primary cycle in each country. The ratio is also

set according to the recommended starting ages in each country, even if enrollment and

attendance ages are poorly promoted or enforced. Sixteen of the 26 countries have recom-

mended starting ages of six, while the other ten have recommended starting ages of seven.

Countries with earlier recommended starting ages may have more difficulty achieving a

higher net primary enrollment ratio than countries with later recommended starting ages.

The UNESCO net primary enrollment ratio is based on first-day enrollments as

officially reported by schools throughout the country to the national ministry of educa-

tion. These enrollment numbers are divided by United Nations estimates of the popula-

tion for the year and ages in question. The quality of these enrollment estimates is di-

rectly tied to the quality of the underlying management information systems on which

they are based. The development of good management information systems is a con-

tinuing challenge in many parts of Africa (Moulton et al. 2001). Where financial flows

to schools are related to the level of enrollment, there is substantial motivation on the

part of local education offices to inflate these numbers. Although changes in systems of

reporting that make current data more accurate are welcome, they may nonetheless com-

promise comparability over time.

Data from the DHS household survey can be used to derive alternative estimates of

primary school participation applicable to the year of the survey. In each of these nationally

representative surveys, data on educational participation and attainment were collected for

every member of the household. Information on current school status was obtained for

those between ages 5 and 24. Because a survey can extend over several months, the

DHS has the disadvantage of capturing households at different stages of the annual

school cycle. While the wording of the DHS question is intended to capture all who are

still enrolled in school, even if they are not currently attending because of illness, school

vacation, or other circumstances, some researchers suggest that the DHS measures of school

participation should be termed measures of attendance rather than measures of enrollment.8

9

The net primary attendance ratio derived from the DHS data is likely to provide a

more realistic picture of school participation than the net primary enrollment ratio de-

rived from the UNESCO data, given that the former includes only those who have actu-

ally attended school and is based on a numerator and denominator that are derived from

the same population base. The DHS estimate also has the advantage that it can be pre-

sented for separate subpopulations, including those grouped by household wealth sta-

tus. While UNESCO provides annual data on trends in the net primary enrollment ratio

for those countries reporting enrollment data by age, such data are not available for all

countries. In the case of sub-Saharan Africa, only 18 of the 26 DHS-surveyed countries

have enrollment data from UNESCO that match within one to two years of the dates of

the DHS survey.

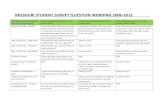

Table 3 compares estimates of the net primary enrollment ratio for boys and girls

from UNESCO and of the net primary attendance ratio from DHS, using the same age

ranges for each country and closely matching dates.9 Figure 1 combines these two estimates

for each country, separately for boys and girls, in scatter plots that relate the pairing of esti-

mates to a 45-degree line representing complete consistency between the two estimates.

While a majority of points lie reasonably close to the diagonal, there is a tendency for the

UNESCO estimates to be higher than those of the DHS.10 This is highlighted in Figure 1 by

the larger number of cases falling, sometimes significantly, below the diagonal. These com-

parisons reinforce suspicions about the inflation of ministry reporting of enrollment in

some countries (Lloyd, Kaufman, and Hewett 2000) and the likelihood that many chil-

dren are enrolled in, but never actually attend, school (UNESCO 2002).

Table 3 also compares two estimates of the gender gap in primary school partici-

pation. The gender gap in enrollment implied by UNESCO estimates is systematically

higher than the gender gap in attendance implied by DHS. These findings suggest a

differential inflation of school participation by sex in the UNESCO estimates, with ei-

ther structural elements built into some management information systems that lead to

this type of inflation for boys or the fact that boys are more likely than girls to be en-

rolled in, yet never attend, school. While norms about the importance of enrolling boys

are likely to be pervasive, norms about girls’ enrollment are probably less strongly held.

As a result, the registration of girls on the first day of school may reflect a strong com-

Tab

le 3

Com

pari

son

of n

et p

rim

ary

enro

llm

ent r

atio

s (U

NE

SC

O)

and

net p

rim

ary

atte

ndan

ce r

atio

s (D

HS

)

Gen

der

gap

Age

Yea

r of

dat

aB

oys

Gir

ls(b

oys

min

us g

irls

)

rang

eU

NE

SCO

DH

SU

NE

SCO

DH

SU

NE

SCO

DH

SU

NE

SCO

DH

S

Ben

in6–

1119

9619

9679

.552

.648

.333

.831

.218

.8B

urki

na F

aso

7–12

1998

1998

–99

40.2

33.0

27.5

22.8

12.7

10.2

Cam

eroo

n6–

11—

1998

—74

.7—

72.8

—1.

9C

entr

al A

fric

an R

ep.

6–11

—19

94–9

5—

64.0

—49

.5—

14.5

Cha

d6–

1119

9619

96–9

759

.036

.732

.824

.226

.212

.5C

omor

os6–

1119

9819

9653

.749

.245

.544

.68.

24.

6C

ôte

d’Iv

oire

6–11

1998

–99

1998

67.5

58.4

50.8

46.4

16.7

12.0

Eth

iopi

a7–

1019

9819

9940

.832

.429

.827

.211

.05.

2G

hana

6–11

—19

98–9

9—

76.8

—76

.1—

0.7

Gui

nea

7–12

1999

–200

019

9956

.431

.341

.423

.915

.07.

4K

enya

6–12

—19

98—

87.2

—86

.9—

0.3

Mad

agas

car

6–10

1998

1997

62.1

58.2

63.5

60.2

–1.4

–2.0

Mal

awi

6–9

—20

00—

73.1

—76

.1—

–3.0

Mal

i7–

12—

2001

—45

.0—

33.5

—11

.5M

ozam

biqu

e6–

1019

9819

9745

.254

.036

.847

.18.

46.

9N

amib

ia6–

1219

9219

9286

.183

.792

.786

.9–6

.6–3

.2N

iger

7–12

1998

1998

31.9

31.2

20.4

21.1

11.5

10.1

Nig

eria

6–11

—19

99—

65.5

—61

.3—

4.2

Rw

anda

7–12

1999

–200

020

0097

.143

.697

.545

.4–0

.4–1

.8S

eneg

al7–

1219

9219

92–9

354

.741

.041

.533

.313

.27.

7S

outh

Afr

ica

7–13

1997

1998

100.

088

.510

0.0

89.9

0.0

–1.4

Tanz

ania

7–13

1999

–200

019

9945

.851

.647

.656

.0–1

.8–4

.4To

go6–

1119

9819

9898

.674

.278

.364

.720

.39.

5U

gand

a6–

12—

2000

–01

—74

.2—

75.8

—–1

.6Z

ambi

a7–

1319

9819

96–9

773

.667

.072

.367

.71.

3–0

.7Z

imba

bwe

6–12

1999

–200

019

9979

.980

.980

.482

.3–0

.5–1

.4

Sour

ces:

UN

ES

CO

(20

02, T

able

6),

Wor

ld B

ank

(200

2), a

nd D

HS

hou

seho

ld f

iles

.

F

F

F

F

F

FF

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

DH

S

UNESCO

Benin

Burkina FasoChad

Comoros

Côte d’Ivoire

Ethiopia Guinea

MadagascarMozambique

Namibia

Niger

RwandaSenegal

South Africa

Togo

Tanzania

Zambia

Zimbabwe

Boys

F

FF

FF

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

DH

S

UNESCO

Benin

Burkina FasoChad

Comoros

Côte d’Ivoire

Ethiopia

Guinea

Madagascar

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Rwanda

Senegal

South Africa

Togo

Tanzania

Zambia

Zimbabwe

Girls

Figure 1 Comparison of net primary enrollment and attendance ratios: UNESCO vs. DHS

Source: Table 3.

12

mitment by parents to their daughters’ regular attendance, whereas first-day enrollments

for boys are likely more routine and less indicative of parental commitment. Regardless

of how these discrepancies are interpreted, UNESCO enrollment estimates imply much

larger gender gaps in school participation than do DHS attendance estimates.

We can also compare UNESCO and DHS data with regard to grade four comple-

tion, the second indicator adopted for monitoring progress toward the millennium edu-

cation goal. The UNESCO estimate for grade four completion, also called the survival

rate at grade five, is a ratio of the number of children officially enrolled in grade five in

a given year relative to the number of children who officially enrolled in grade one four

years earlier.11 This may or may not capture the actual percent of any particular school-

entering cohort that completes grade four, because it does not account for any repetition

or temporary withdrawal. It is also not restricted to children of a common age. In coun-

tries with high repetition or withdrawal, this statistic would underestimate the percent of

children who eventually complete grade four. An alternative measure that can be de-

rived from the DHS, and that does not have these limitations, is the percent of 15–19-

year-olds who have completed four or more years, among those who have ever entered

school. This measure accommodates late starters and allows comparisons across age

cohorts. It is, however, less contemporaneous than the UNICEF indicator.12

Table 4 compares alternative estimates of grade four completion derived from

UNESCO and from DHS. Data for this indicator are available from UNESCO for 18 of

the 26 countries. Figure 2 presents scatter plots of points derived from the data in Table

4. With one or two exceptions, DHS estimates are higher than UNESCO’s for both boys

and girls. We suspect this is because the DHS measure is not time bound and includes

students who take more than four years to complete grade four. Where comparisons are

possible, half the countries show gender gaps that are roughly consistent in magnitude

while half show gender gaps that are inconsistent in magnitude, and sometimes even of

inconsistent signs. These inconsistencies cannot be readily explained, thus raising ques-

tions about the cross-country comparability of these estimates.

From these comparisons, we conclude that UNESCO provides an incomplete

and sometimes potentially biased picture of progress toward the millennium education

goal with the current data derived from country management information systems. Com-

Tab

le 4

Com

pari

son

of g

rade

fou

r co

mpl

etio

n es

tim

ates

: UN

ES

CO

vs.

DH

S

Gen

der

gap

Yea

r of

dat

aB

oys

Gir

ls(b

oys

min

us g

irls

)

UN

ESC

OD

HS

UN

ESC

OD

HS

UN

ESC

OD

HS

UN

ESC

OD

HS

Ben

in19

9719

9664

.072

.557

.063

.37.

09.

2B

urki

na F

aso

1998

–99

1998

–99

66.9

80.3

70.4

84.5

–3.5

–4.2

Cam

eroo

n—

1998

—86

.8—

88.0

—–1

.2C

entr

al A

fric

an R

epub

lic

—19

94–9

5—

66.7

—57

.1—

9.4

Cha

d19

9719

96–9

762

.057

.853

.042

.79.

015

.1C

omor

os—

1996

—75

.2—

74.9

—0.

3C

ôte

d’Iv

oire

1997

1998

–99

77.0

87.0

71.0

81.6

6.0

5.4

Eth

iopi

a19

9719

9951

.054

.850

.054

.31.

00.

5G

hana

—19

98–9

9—

93.5

—92

.8—

0.6

Gui

nea

1998

–99

1999

92.5

87.8

79.1

80.7

13.4

7.1

Ken

ya—

1998

—93

.1—

93.8

—–0

.7M

adag

asca

r19

9719

9749

.052

.033

.055

.116

.0–3

.1M

alaw

i—

2000

—75

.9—

77.8

—–1

.9M

ali

—20

01—

86.4

—84

.7—

1.7

Moz

ambi

que

1997

1997

52.0

64.2

39.0

50.3

13.0

13.9

Nam

ibia

1991

1992

60.9

75.1

65.5

85.8

–4.6

–10.

7N

iger

1998

–99

1998

62.1

87.2

60.2

86.0

1.9

1.2

Nig

eria

—19

99—

96.5

—95

.2—

1.3

Rw

anda

1998

–99

2000

47.9

67.0

42.8

66.5

5.1

0.5

Sen

egal

1993

1992

–93

83.2

89.9

78.0

87.4

5.2

2.5

Sou

th A

fric

a19

98–9

919

98–0

075

.197

.476

.798

.8–1

.6–1

.4Ta

nzan

ia19

98–9

919

9978

.683

.083

.388

.0–4

.7–5

.0To

go19

98–9

919

9854

.277

.348

.468

.05.

89.

3U

gand

a19

98–9

920

00–0

143

.985

.545

.582

.3–1

.62.

2Z

ambi

a19

98–9

919

96–9

783

.586

.973

.085

.710

.51.

2Z

imba

bwe

1997

1999

78.0

96.3

79.0

97.2

–1.0

–0.9

Sour

ces:

UN

ES

CO

(20

02, T

able

10)

, Wor

ld B

ank

(200

2), a

nd D

HS

hou

seho

ld f

iles

.

Figure 2 Comparison of alternative estimates of grade four completion rates:UNESCO vs. DHS

Source: Table 4.

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

FF

F

F

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

DH

S

UNESCO

Benin

Burkina Faso

Chad

Côte d’Ivoire

Ethiopia

Guinea

Madagascar

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Rwanda

SenegalSouth Africa

Togo

Uganda Tanzania Zambia

ZimbabweBoys

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

FF

F

F

F

F

F

FF

F

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

DH

S

UNESCO

Benin

BurkinaFaso

Chad

Côte d’Ivoire

Ethiopia

Guinea

Madagascar

Mozambique

NamibiaNiger

Rwanda

Senegal

South Africa

Togo

Uganda

TanzaniaZambia

ZimbabweGirls

15

parisons with data from the DHS suggest that fewer children ever attend school than the

UNESCO estimates suggest, but a higher percentage of those who do attend eventually

complete grade four. Furthermore, gender gaps in school participation are likely to be

smaller than implied by UNESCO enrollment estimates. In the next section of the paper,

we rely entirely on DHS data to derive country-specific as well as region-wide trends. In

our view, these data provide an alternative and potentially more accurate portrayal of

past educational achievement and current challenges than trends derived from the

UNESCO data previously discussed.

TRENDS IN EDUCATIONAL PARTICIPATION

AND ATTAINMENT

Trends in schooling can be derived using the most recent DHS survey for each

country by comparing cohort differences in educational participation and attainment.

We look primarily at two indicators of progress: (1) the percent completing four or more

grades and (2) the percent completing primary school. Unlike the indicator of grade four

completion reviewed in the previous section, which is restricted to those who ever at-

tended, the DHS measure used here is calculated to include all individuals within each

age group.

To ensure comparability across cohorts, the youngest five-year age cohort cho-

sen for each indicator has to have reached a sufficient age to be assured of achieving the

level of schooling captured by that indicator.13 In the case of the percent completing four

or more grades, a minimum age of 15 is required for this measure in light of late starting

ages (Table 2); not all children can safely be assumed to complete grade four until age

15 in many sub-Saharan African countries. For the second indicator—completed pri-

mary school—the base cohort is 20–24-year-olds because, in countries with longer pri-

mary cycles, students may still be enrolled in primary school at age 18 (Lloyd, Mensch,

and Clark 2000).

Several advantages are associated with deriving trends from a single survey. First,

one can compare more countries, as only 15 of the 26 countries have had more than one

DHS survey since 1990, the year when DHS added education to the household question-

naire. Second, the mean interval between surveys is no more than six years, and one can

explore trends over a longer interval of time using a single survey. Third, there is inter-

16

nal comparability within one sample survey that cannot necessarily be assumed when

comparing more than one survey.14

On the other hand, there is some loss in comparability when deriving long-term

trends from one survey, owing to differential mortality by educational attainment. Some

of those educated in the past will not be alive at the time of the survey and, therefore,

their educational attainment will not be reported. Mortality will be selective of the least

educated and will therefore lead to an overestimate of educational attainment in earlier

time periods, thus biasing down estimated rates of progress. Indicators for the current

period are not affected by differential mortality. Because mortality rates are relatively

low for individuals in their 20s and 30s, this is likely to be a minor source of bias for

trend estimates over the last two decades.

Table 5 presents trends in indicators of educational participation and attainment

for sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, separately for males and females. For comparability,

data are shown for the percent who have ever attended school, including estimates for the

youngest age cohort, those aged 10–14, as well as for the two indicators of educational

attainment. The trends in Table 5 are based on weighted averages, using the population

aged 10–24 in 2000 (as estimated by the United Nations) as the weight for each country.15

Given that the trends for all three indicators track very closely together over the age co-

horts, it is possible to bring the estimates of grade four completion and primary school

completion up-to-date by estimating grade four completion rates for 10–14-year-olds and

completed primary school rates for those aged 15–19 and 10–14.16 As a result we can

present trends in both indicators of educational attainment up through the late 1990s.

These are illustrated in Figure 3.

For boys, the percent completing primary school is estimated to have risen in

sub-Saharan Africa from roughly 46 percent in the late 1960s to roughly 57 percent in

the late 1990s. However, the primary school completion rates have stayed the same

since the early 1980s. Indeed, most of the improvement in primary completion came in

the 1960s and 1970s. In fact, boys in sub-Saharan Africa have recorded little progress in

the percent completing primary school in the last 30 years.

In stark contrast, over the same time period girls’ primary school completion

rates have risen steadily from a much lower base of around 26 percent to 53 percent,

17

roughly doubling the level of achievement since the 1960s. The pace of progress for

girls, which was very rapid earlier on, has slowed in the last 20 years. For girls, these

trends reflect not only an increase in attendance, but also a small improvement in reten-

tion rates. With these different trajectories, the gender gap, which was very wide in the

early days of independence, has narrowed considerably: current estimates for sub-Sa-

haran Africa as a whole put the gap at only 4 percentage points in favor of boys.

Grade four completion rates are slightly higher than primary completion rates for

both boys and girls, implying an attrition rate between the end of grade four and primary

completion of roughly 10 percentage points. In the current period, an estimated 63 per-

cent of girls and 68 percent of boys aged 10–14 have completed at least four grades.

Two worrying developments for boys are the stagnation in grade four completion for the

last 15 to 20 years at around 68 percent and the small recent decline from 69 to 68

percent. While 80 percent of 15–19-year-old boys had ever been to school, the percent

has fallen to 78 percent for the 10–14-year-olds (see Table 5). This suggests the possibil-

ity of a future erosion in boys’ schooling attainment for the next decade. Given that

Table 5 Trends in educational participation and attainment (percent) weighted bypopulation, 26 African countries

Ever attended school Completed 4+ years Completed primary

Gender Gender GenderAge group Males Females gapa Males Females gapa Males Females gapa

10–14 77.8 72.2 5.6 68.2* 63.3* 4.9* 57.2* 52.9* 4.3*15–19 80.4 70.8 9.5 68.3 60.4 7.9 57.3* 50.1* 7.2*20–24 78.2 66.1 12.1 68.9 57.9 10.9 57.3 47.2 10.125–29 76.3 63.4 13.0 68.1 55.1 13.0 56.9 44.4 12.530–34 73.7 58.0 15.7 65.6 49.4 16.2 55.5 39.3 16.135–39 71.9 51.1 20.8 63.8 42.6 21.2 53.5 32.9 20.640–44 65.2 44.0 21.2 56.3 34.9 21.4 45.8 25.9 19.9Change for mostrecent decade –0.5 9.3 –54.0 –0.1 9.3 –55.0 0.0 12.1 –57.4

Change forearlier decade 6.1 14.0 –23.1 5.0 17.2 –32.7 3.2 20.1 –37.3

Changeover 20 years 5.5 24.6 –64.6 4.0 28.1 –69.8 3.1 34.6 –73.3

aMales minus females.*Estimates prepared by authors.Note: Weighting based on 2000 UN estimates for population 10–24.Source: DHS data files

F

FF

F F

46

54 56 57 57

B

B

B

BB

26

3339

4447

F F F

57 57 57

BB

B

4750

53

40–44 35–39 30–34 25–29 20–24 15–19 10–140

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Perc

ent

Age range

F Boys B Girls F Authors’ estimates B

Completed primary

F

FF

F F F

56

64 66 68 69 68

B

B

B

BB

B

35

4349

5558 60

F F

68 68

BB

6063

40–44 35–39 30–34 25–29 20–24 15–19 10–140

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Perc

ent

Age range

F Boys B Girls F Authors’ estimates B

Completed 4+ years

late 1960s late 1990searly 1990slate 1980searly 1980slate 1970searly 1970s

late 1960s late 1990searly 1990slate 1980searly 1980slate 1970searly 1970s

Figure 3 Trends in educational attainment: 26 African countries

Source: DHS data.

19

these weighted regional averages hide the current achievement of a large number of

poorly performing countries, many countries will witness even greater declines in edu-

cation among boys.

As with primary school completion rates, grade four completion rates for girls

have increased markedly over time, although clearly a large part of the growth was

for older age cohorts. As a result, the estimated gender gap for grade four comple-

tion has declined to 5 percentage points for the late 1990s. With the decline in boys’

attendance coupled with increases in girls’ attendance and grade four completion, girls

are likely to meet or surpass boys on this indicator in the near future. However, although

attendance and grade four completion for girls continue to increase, the pace of these

trends is much slower than in the past. It is possible that the trends in girls’ school-

ing will eventually parallel the flatter trends for boys that have occurred in the last

three decades or so.

These long-term trends mirror economic and political developments for the re-

gion as a whole. In the early postcolonial period, the importance accorded to schooling

in national development plans led to a dramatic increase in educational expenditure and

a tremendous expansion of educational infrastructure, irrespective of differing develop-

ment strategies.17 These investments were facilitated by strong economic growth rates

in the late 1960s and the 1970s (Kinyanjui 1993; World Bank 1988). Total public expen-

diture on education in constant dollars grew on average by roughly 7 percent a year

between 1970 and 1980 across sub-Saharan Africa, with similar rates of growth re-

corded in the former British and French colonies. These average rates of growth were

well above those required to keep pace with the growth in school-age populations (Do-

nors to African Education 1994). Indeed, growth of educational expenditure exceeded

growth in gross national product (GNP) in the 1970s, resulting in a rising fraction of

GNP devoted to educational expenditure.

The economic, political, and demographic conditions in the 1980s, however,

sharply curtailed and often ended the impressive educational gains of the previous two

decades. Population continued to grow rapidly, with rates of growth in most countries

even higher in the 1980s than in the 1970s (United Nations 2001). African countries

were particularly hard hit by increased world prices for oil, decreased export prices, and

20

higher external debt (Hodd 1989; World Bank 1988). Additionally, most countries adopted

structural adjustment programs that resulted in cutbacks in social-sector spending, in-

cluding educational expenditures, often leading to the imposition of school fees (Reimers

1994).18 This retraction of national investment in education is reflected in declines in the

growth rate of educational expenditures in constant dollars from 6.2 percent on average

for 1970–80 to 2.1 percent for 1980–90 (Donors to African Education 1994).

In addition to economic decline in the region, for many other countries in Africa

during the 1970s and 1980s (for example, Angola, Ethiopia, Liberia, Mozambique, Ni-

geria, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Sudan) political instability and internal conflict re-

sulted in marked declines in education and its infrastructure, including a reduction in the

depth and breadth of educational development (Kinyanjui 1993). For example, nine

years after the Amin coup in 1971, Uganda had the lowest per-pupil spending levels

among all sub-Saharan countries, and this pattern continued until 1990 (Donors to

African Education 1994). In Nigeria, political instability led to a continuous decline

in educational expenditures averaging 15.7 percent per year during the 1980s (ibid.).

The impact of instability and conflict on education was no less relevant in the 1990s

for countries such as Burundi, Congo, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and most recently Côte

d’Ivoire. The good news is that, as Mozambique and Uganda have emerged in the

1990s from their tragic earlier history, they have shown impressive recent gains in edu-

cational indicators.

Because some of the most populous countries in Africa, measured in terms of the

size of their adolescent population in 2000, have achieved higher levels of schooling

than their smaller neighbors, weighted averages give a more optimistic picture of the

trends in schooling than would be the case if each country were given the same weight

in the analysis.19 The most populous countries that have participated in the DHS survey

program with relatively strong educational performance include Nigeria with 37.6 mil-

lion 10–24-year-olds, South Africa with 13.7 million, Tanzania with 11.8, Kenya with

11.3, Uganda with 7.8, and Ghana with 6.6. Of the more populous countries, only Ethio-

pia, with 20 million 10–24-year-olds, has had relatively poor educational performance.

Thus, more than half the countries represented in this analysis face even greater chal-

lenges in achieving “Education for All” than would be implied by these data.

21

The range of experience across countries in grade four completion and primary

school completion, and patterns of recent changes, are depicted in Figure 4, using a

scatter plot to array each indicator for boys and girls separately at two points in time.

Points to the left of the diagonal line indicate a growth in attendance in the recent decade

and points to the right of the line indicate recent declines. For the percent completing

grade four, shown in the top panel of Figure 4, half of the countries in our sample have

recent grade four completion rates for girls below 50 percent while, in the case of boys,

this is true for roughly a third of our sample countries. On the other hand, in the past ten

years girls are more likely to have shown improvements in grade four attainment rela-

tive to boys. From the bottom panel of Figure 4, we can see that no country has achieved

universal primary school completion. Indeed, primary completion rates for most coun-

tries fall below 50 percent. Again girls are more likely to have experienced recent im-

provements than boys.

Appendix Tables 1 and 2 present data on the performance of individual countries

for each indicator. Looking at the range of experience across the 26 countries, we see

tremendous variation in performance over time, by sex, by decade, and by indicator.

Again, the majority of countries fall below the levels of schooling implied by the weighted

averages presented in Table 5.

Starting with trends in grade four completion rates in Appendix Table 1, we see that

over a 20-year period (comparing the cohort aged 15–19 with the cohort aged 35–39), three

countries have seen sharp declines in grade four completion for boys: Madagascar, Tanza-

nia, and Zambia. In the more recent past, many more countries have experienced setbacks

in grade four completion for boys, including Cameroon, Central African Republic, Côte

d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, Namibia, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe. Girls have also experienced

setbacks in grade four completion rates in the last decade in Côte d’Ivoire, Madagascar,

Rwanda, and Tanzania. Mali and Mozambique, which had experienced declines for boys in

the earlier decade, recorded impressive growth in the recent decade, more than erasing

earlier losses. Again, in all 26 countries, the gender gap in grade four completion has nar-

rowed, with the most dramatic percentage changes in French West Africa where the largest

absolute gaps still remain. For example, in Benin, Central African Republic, Guinea,

Mozambique, and Togo the gender gap still exceeds 20 percentage points.

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Perc

ent a

ged

15–1

9

Percent aged 25–29

B Girls

F Boys

Completed 4+ years

Figure 4 Trends in educational attainment: 26 African countries

Source: Appendix Table 1.

Source: Appendix Table 2.

BB

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

FF

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

FF

F

F

F

F

F

F

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Perc

ent a

ged

20–2

4

Percent aged 30–34

B Girls

F Boys

Completed primary

23

In the most recent decade for which comparisons are possible (cohort aged 20–24

compared with the cohort aged 30–34), ten countries have seen declines in primary

completion rates for boys (Appendix Table 2). These are Benin, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mada-

gascar, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Togo, and Zambia. Three of these

have also seen declines for girls: Benin, Kenya, and Madagascar. During this same de-

cade, most of the same countries saw increases in attendance rates, suggesting the diffi-

culties not only of entering school but also of staying in school until the end of the

primary cycle. These declines in attendance and retention in different countries at differ-

ent points in time remind us that, in the context of economic, political, and bureaucratic

uncertainty, steady progress cannot be taken for granted.

CURRENT CHALLENGES

In the 1990s, qualitative evaluations of the educational situation in sub-Saharan

Africa described a thinning of the provision of education and the inability of countries

to maintain current levels of educational achievement given lagging growth in invest-

ment and continuing growth in the size of school-age cohorts (Kinyanjui 1993;

Nieuwenhuis 1996). While UNESCO provides recent estimates of total public expendi-

ture on education as a percent of GNP for 17 of the 26 countries in our sample (UNESCO

2002), it is difficult to link these estimates with data from earlier time periods because of

noncomparability in the accounting of expenditure.20

In response to these negative trends and in light of the goal of Education for All

set in Jomtien in 1990, many African countries adopted educational reform measures in

the 1990s, usually in collaboration with international donors, to improve efficiency, mo-

bilize resources, and reallocate expenditures away from tertiary and toward more basic

levels of schooling (Samoff and Sumra 1994). Two key elements of school reform in

many contexts have been policies to decentralize governance structures (including devo-

lution of responsibility for educational delivery to lower levels of government, parent–

teacher associations, and the involvement of the private sector) and policies to achieve

greater financial accountability (such as the imposition of user fees). A recent analysis

by Colclough and Al-Samarrai (2000) suggests that Education for All is achievable within

current budget constraints if governments give greater budgetary priority to the primary

24

sector and reduce unit costs of schooling by improving efficiency and controlling teacher

salaries in countries where they are relatively high.

Current educational reform efforts are faring very differently in different con-

texts. A review of recent reform efforts in Benin, Ethiopia, Guinea, Malawi, and Uganda

suggests that the process has been more complicated and expensive than originally an-

ticipated (Moulton et al. 2001). In each of these five cases, external donor funds from

USAID and the World Bank represent a substantial share of current public expenditures

on education, ranging from 14–15 percent in Ethiopia and Uganda to as high as 43

percent in Guinea.21 Not one of these countries has been able to implement more than

some aspects of the very elaborate plans that have been adopted. While all ministries

reallocated more funds to primary education, Benin, Guinea, and Malawi were not able

to allocate those monies effectively so as to benefit individual schools. Ministries are

still struggling to create effective management information systems. Some attempt has

been made to train more teachers and the production and delivery of educational mate-

rials has improved, but the process of revising the curriculum has just begun.

While we are unaware of internationally comparable data on levels and trends in

the distribution of school costs between various levels of government and parents them-

selves, many country case studies document increases in school fees and complemen-

tary out-of-pocket costs, such as for textbooks and uniforms (Mehrotra and Delamonica

1998; Grootaert 1994; Bradshaw and Fuller 1996). This widespread rise in the share of

total schooling costs paid by parents has taken different forms depending on the context

(Knowles and Behrman 2003). However, in a few countries that have returned to multi-

party rule with democratic elections, school fees have been abolished in response to

pressure from the electorate—for example, in Malawi and Uganda (Moulton et al. 2001)

and, most recently, Kenya (Lacey 2003). These decisions, driven by political consider-

ations, have led to strains in the system as enrollments shot up overnight without corre-

sponding changes in facilities and staffing. Clearly, given popular aspirations and inter-

national insistence, African governments are under increasing pressure to achieve

universal primary schooling. At the same time, financial constraints are making it ex-

ceedingly difficult to raise enrollment rates without jeopardizing educational quality

and, by extension, retention rates in the longer term.

25

While UNESCO data do not allow us to explore differential attainment of Educa-

tion for All goals by household wealth status, this is possible with DHS data. This fact

provides a particular advantage to the DHS data for monitoring educational levels and

attainment, given that many current reform efforts are attempting to target resources where

they are most needed. Using the household wealth index created by Filmer and Pritchett

(1999), we developed an index of educational inequality by household wealth. The in-

equality index is calculated as one minus the ratio of the grade four attainment of the

poorest 40 percent of households, relative to the wealthiest 20 percent of households. This

measure of educational inequality ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 representing complete parity

of attainment between the richest 20 percent and the poorest 40 percent in a given country

and a value of 1 indicating a complete lack of educational opportunities for the poor. A

measure of 0.5 implies that the poor have reached 50 percent of the levels of attainment of

the rich. Because household wealth status is measured at the time of the survey, not at the

time when schooling decisions are made, we present results for grade four completion

rather than primary completion because the former are available for a younger age group.

Table 6 presents the inequality index for grade four completion by wealth status for

boys and girls separately as well as the gender gap. The 26 countries are ordered from high to

low inequality using the index for boys as the baseline. The first 11 countries listed have

indexes for both boys and girls that exceed .50, suggesting wide differentials in educational

attainment by household wealth status in sub-Saharan Africa. In most of these countries, the

inequality index takes on extreme values ranging between .70 and .90, indicating almost a

complete lack of educational opportunities for the poorest segment of the population. A few

additional countries have levels of inequality that exceed .50 only for girls, namely Côte

d’Ivoire, Togo, and Comoros. On the other hand, the last three countries listed in the table

have achieved universal schooling even for the poor. Relatively low indexes around .20 can

be seen for both sexes in Rwanda and Ghana, for boys in Tanzania, and for girls in Namibia.

In many countries, the index of inequality is substantially higher for girls than

boys, supporting the widely held belief that gender inequalities in educational attain-

ment are magnified among the poor. Differences of 10 percentage points or more in the

index between boys and girls can be found in 14 of the 26 countries. Such gender differ-

ences tend to be greatest in countries where overall wealth inequalities are greatest. It is

26

interesting to note, however, that this pattern is not universal. Indeed in a substantial

minority of countries, representing the full range in terms of schooling inequalities by

household wealth status, we find similar levels of inequality for boys and girls. And in

several countries inequalities for boys are greater than those for girls: Madagascar,

Namibia, Zambia, Rwanda, Ghana, and South Africa.

Figure 5 contrasts the levels of grade four completion currently achieved by 15–

19-year-olds from the poorest 40 percent and the wealthiest 20 percent of households.

Countries are ordered from low to high according to the grade attainment of boys in the

poorest households. Nearly universal grade four attainment for the poor has been achieved

Table 6 Index of inequality in grade four completion for 15–19-year-olds, byhousehold wealth

Gender gapCountry Boys Girls (boys minus girls)Mali 0.87 0.91 –0.04Burkina Faso 0.83 0.90 –0.07Madagascar 0.77 0.74 0.03Ethiopia 0.76 0.90 –0.14Benin 0.74 0.93 –0.19Senegal 0.73 0.84 –0.11Guinea 0.71 0.93 –0.22Chad 0.70 0.91 –0.21Niger 0.69 0.91 –0.22Mozambique 0.64 0.83 –0.19Central African Republic 0.56 0.84 –0.28Côte d’Ivoire 0.48 0.67 –0.19Cameroon 0.38 0.46 –0.08Namibia 0.38 0.22 0.16Togo 0.37 0.57 –0.20Zambia 0.35 0.32 0.03Nigeria 0.34 0.48 –0.14Comoros 0.32 0.66 –0.34Uganda 0.29 0.45 –0.16Malawi 0.28 0.28 —Rwanda 0.24 0.22 0.02Ghana 0.21 0.19 0.02Tanzania 0.21 0.35 –0.14South Africa 0.06 0.04 0.02Zimbabwe 0.04 0.06 –0.02Kenya 0.03 0.04 –0.01

Note: Countries are listed in descending order by index value for boys. For a description of the index see text.Source: DHS data.

Figure 5 Grade four completion, 15–19-year-olds

Note: Countries in both panels are listed in ascending order by educational attainment of boys in the poorest 40percent of households.Source: DHS data.

Bur

kina

Fas

oE

thio

pia

Mad

agas

car

Cha

dB

enin

Nig

erM

ali

Sene

gal

Gui

nea

Moz

ambi

que

C.A

.R.

Côt

e d’

Ivoi

reR

wan

daC

omor

osT

ogo

Cam

eroo

nN

amib

iaT

anza

nia

Mal

awi

Nig

eria

Zam

bia

Uga

nda

Gha

naK

enya

Sout

h A

fric

aZ

imba

bwe0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100Pe

rcen

t

Boys Girls

Poorest 40% of households

Bur

kina

Fas

oE

thio

pia

Mad

agas

car

Cha

dB

enin

Nig

erM

ali

Sene

gal

Gui

nea

Moz

ambi

que

C.A

.R.

Côt

e d’

Ivoi

reR

wan

daC

omor

osT

ogo

Cam

eroo

nN

amib

iaT

anza

nia

Mal

awi

Nig

eria

Zam

bia

Uga

nda

Gha

naK

enya

Sout

h A

fric

aZ

imba

bwe0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Perc

ent

Boys Girls

Wealthiest 20% of households

28

only in Kenya, South Africa, and Zimbabwe for both boys and girls. For the first 11

countries, most of them in Francophone Africa, grade four completion rates for the poor

rarely exceed 20 percent for boys or 10 percent for girls. The gender gaps appear larger

in countries where grade four attainment for boys is comparatively low. On the other

hand, looking at grade four completion rates for the richest 20 percent, many countries

have already achieved universal attainment. For many others, such achievement is likely

within the next 15 years. For a few countries, however, even the richest 20 percent have

far to go. This group includes some of the poorest countries: Burkina Faso, Ethiopia,

Chad, Niger, and Mali. While the gender gap among children from the richest house-

holds has narrowed or almost disappeared in the majority of countries, this is not the

case in much of Francophone Africa, including Burkina Faso, Chad, Benin, Niger, Mali,

Senegal, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo. Gender gaps among the rich remain large in

Ethiopia and Mozambique as well.

These results suggest that educational reform measures should be tailored to each

country’s situation and should be based on recent and accurate measures of the perfor-

mance of different subgroups. At the country level, DHS data permit other breakdowns

as well, including provincial and rural/urban breakdowns. While many of these break-

downs could be developed within a well-designed management information system,

such would not be the case for household wealth indicators, which require data collected

at the household level. Given the enormous financial and organizational mobilization

that will be required to achieve the millennium education goals, resources will need to

be targeted to the particular population subgroups that are lagging behind. A proper

monitoring program will require information on the relative progress of the poor.

CONCLUSIONS

At the dawn of the twenty-first century we estimate that 37.2 million young ado-

lescents aged 10–14 in sub-Saharan Africa will not complete primary school. This num-

ber is nearly twice the entire population of children aged 10–14 in the United States,

virtually all of whom will complete primary school.22 Reducing the number of unedu-

cated African youth is a primary objective of the United Nations as set forth in the

Millennium Development Goal for education (United Nations 2001). Achieving this

29

goal will require a level of resources and commitment not previously seen; it will also

require better tools for monitoring progress.

We conclude from our assessment of UNESCO’s two complementary indicators

for monitoring progress toward Education for All that UNESCO data provide at best an

incomplete and at worst a biased picture of levels, trends, and gender differences in

primary school participation and grade attainment. Part of the problem arises from

UNESCO’s reliance on disparate management information systems across countries to

collate information about children’s levels of schooling. This results in the publication

of data of variable quality, with limited comparability across countries and over time.

The current exclusive reliance of the international community on UNESCO data to track

progress toward the millennium goals is misplaced. If there were a more transparent

system for collecting schooling information from national ministries, the reliability of

UNESCO indicators on a national basis could be evaluated. In the absence of good local

management information systems, education data derived from nationally representa-

tive surveys fielded on a periodic basis would prove highly useful as an additional, and

sometimes alternative, source of data for monitoring progress toward the goal of Educa-

tion for All.

The Demographic and Health Surveys provide a useful baseline from which to

build. Since 2000, household questionnaires have been expanded to allow for the cre-

ation of additional schooling indicators, including some that closely parallel commonly

used UNESCO indicators. Furthermore, the DHS is beginning to launch in-depth sur-

veys on education in sub-Saharan Africa in conjunction with its regular surveys. The

first report has recently been published on Uganda; results for Malawi and Zambia will

follow shortly. This effort would require substantial expansion if it were to take on moni-

toring of educational attainment more broadly.

Even with the limited education data already collected in the traditional DHS

surveys, however, much can be learned about past trends and the current status of school-

ing in sub-Saharan Africa. The trends in primary school completion implied by these

data raise questions about the feasibility of achieving the millennium education goal in

the foreseeable future. It is even possible some earlier gains could be lost, given recent

declines in attendance and attainment among the youngest boys in many countries. It

30

also appears that the gap between boys and girls is closing rapidly in all countries de-

spite huge variations in overall levels of educational attainment. Consequently, these

findings raise doubts about the likelihood that goals of universal education can be achieved

with a strategy limited to an emphasis on girls’ schooling.

The education gap between girls and boys has declined largely because of the

impressive improvement in schooling for girls in sub-Saharan Africa. Although a large

portion of this change occurred decades ago, growth continued in girls’ education in the

1980s and 1990s, despite significant economic setbacks. A thorough understanding of

the reasons for disparate trends in boys’ and girls’ education over the past 30 years will

require more research. Our data do not allow us to tease out the many possibilities,

which might include rising returns to the education of girls (either market or nonmarket),

the diffusion of global cultural values relating to the importance of girls’ schooling, and

the effects of school reform.

Although limits to girls’ schooling do not seem to be a major impediment to

achieving Education for All, wide disparities remain in schooling by economic status. In

short, the schooling gap that remains is the gap between the poorest and wealthiest

households. Others have also posited the importance of household wealth vis-à-vis school-

ing. Filmer and Pritchett (1999) documented the gap in primary school completion rates

according to household wealth status using data from many of the DHS surveys avail-

able a few years ago. Even earlier, Knodel and Jones (1996), using schooling data from

Thailand and Vietnam, raised questions about the heavy emphasis on girls’ schooling in

the international community given the much wider gaps in schooling by household wealth.

This paper offers a new comparison of the size of gender gaps and wealth gaps in most

countries of sub-Saharan Africa using several widely accepted schooling indicators. With

the gender gap closing in many countries at levels of educational attainment that fall

well short of universal primary schooling, new strategies must be devised to reach the

poorest parents and their children.

App

endi

x T

able

1T

rend

s in

the

perc

ent c

ompl

etin

g 4+

yea

rs o

f sc

hool

ing,

by

age

grou

p: 2

6 su

b-S

ahar

an A

fric

an c

ount

ries

Cha

nge

for

Cha

nge

for

mos

t rec

ent

earl

ier

Cha

nge

over

Surv

eyP

opul

atio

n15

–19

25–2

935

–39

deca

de (%

)de

cade

(%)

20 y

ears

(%)

Cou

ntry

date

aged

10–

24B

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

ls

Ben

in19

962,

115

4625

4522

3711

2.2

18.1

22.0

105.

524

.614

2.5

Bur

kina

Fas

o19

98–9

93,

976

3018

2110

138

41.5

84.9

62.7

31.8

130.

314

3.7

Cam

eroo

n19

984,

996

7872

8265

7354

–5.2

10.3

13.1

20.9

7.2

33.4

Cen

tral

Afr

ican

Rep

ubli

c19

94–9

51,

199

5635

5832

5218

–3.6

7.9

10.6

82.7

6.7

97.2

Cha

d19

96–9

72,

491

3614

348

297

7.4

83.1

16.2

8.9

24.8

99.4

Com

oros

1996

240

6449

6344

3515

2.3

12.2

79.3

189.

383

.322

4.5

Côt

e d’

Ivoi

re19

98–9

95,

595

5741

5943

5027

–3.2

–5.9

16.9

59.3

13.2

50.0

Eth

iopi

a19

9919

,988

3121

3720

298

–16.

16.

724

.914

5.9

4.8

162.

4G

hana

1998

–99

6,58

185

7984

6277

601.

526

.78.

73.

810

.331

.5G

uine

a19

992,

637

4925

3515

3112

38.7

65.9

13.5

25.5

57.4

108.

2K

enya

1998

11,3

0691

9193

8991

72–2

.52.

32.

322

.5–0

.325

.3M

adag

asca

r19

975,

025

4143

5756

5542

–28.

1–2

2.4

4.4

32.1

–25.

02.

5M

alaw

i20

003,

722

7272

7048

6638

3.3

49.2

4.8

25.6

8.2

87.3

Mal

i20

013,

652

3523

2514

2515

41.1

64.3

–1.2

–5.8

39.4

54.8

Moz

ambi

que

1997

5,84

856

3450

3052

1813

.013

.9–5

.067

.47.

490

.6N

amib

ia19

9257

270

8274

7970

65–5

.54.

06.

721

.30.

826

.2N

iger

1998

3,50

536

1827

1516

733

.121

.169

.410

8.9

125.

415

2.9

Nig

eria

1999

37,6

3783

7379

6476

484.

914

.55.

033

.510

.152

.9R

wan

da20

002,

689

5757

6562

5237

–12.

1–8

.225

.269

.010

.155

.2S

eneg

al19

92–9

33,

082

4634

3821

3518

18.5

64.4

9.8

12.2

30.2

84.4

Sou

th A

fric

a19

98–0

013

,715

9698

9391

8984

3.3

6.6

4.7

8.8

8.1

16.0

Tanz

ania

1999

11,8

4573

7083

7885

54–1

0.9

–9.2

–2.7

43.3

–13.

330

.2To

go19

981,

496

6947

6433

6127

7.7

44.3

4.9

22.7

12.9

77.0

Uga

nda

2000

–01

7,75

783

7478

5871

466.

127

.19.

725

.616

.459

.6Z

ambi

a19

96–9

73,

521

8178

8775

9071

–7.8

4.9

–2.9

5.2

–10.

510

.3Z

imba

bwe

1999

4,48

995

9597

9491

72–2

.01.

06.

730

.74.

532

.1

Sour

ce:

DH

S d

ata.

App

endi

x T

able

2T

rend

s in

the

perc

ent c

ompl

etin

g pr

imar

y sc

hool

, by

age

grou

p: 2

6 su

b-S

ahar

an A

fric

an c

ount

ries

Cha

nge

for

Cha

nge

for

2000

mos

t rec

ent

earl

ier

Cha

nge

over

Surv

eypo

pula

tion

20–2

430

–34

40–4

4de

cade

(%)

deca

de (%

)20

yea

rs (%

)

Cou

ntry

date

aged

10–

24B

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

lsB

oys

Gir

ls

Ben

in19

962,

115

2711

3312

206

–18.

4–6

.963

.510

7.9

33.4

93.5

Bur

kina

Fas

o19

98–9

93,

976

2512

156

124

72.4

89.2

24.2

61.4

114.

120

5.3

Cam

eroo

n19

984,

996

6960

6743

5731

2.9

39.7

17.9

40.5

21.3

96.3

Cen

tral

Afr

ican

Rep

ubli

c19

94–9

51,

199

4022

3818

266

5.1

24.5

45.6

210.

853

.028

7.0

Cha

d19

96–9

72,

491

297

214

172

40.8

72.2

22.8

123.

172

.928

4.2

Com

oros

1996

240

5141

4826

207

5.3

58.3

140.

129

0.0

152.

951

7.5

Côt

e d’

Ivoi

re19

98–9

95,

595

4634

4427

3728

6.5

27.0

16.8

–3.7

24.3

22.3

Eth

iopi

a19

9919

,988

2314

258

163

–7.6

75.6

51.7

209.

940

.144

4.2

Gha

na19

98–9

96,

581

8062

7451

7349

7.0

21.8

1.6

5.1

8.8

28.0

Gui

nea

1999

2,63