What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

-

Upload

david-bailey -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 1/48

1---'

I~- ..··w'

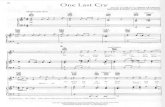

What Is

ForniCriticism?

by

Edgar V. McKnight

r . : 1 I I I.J'-1..

Fortress Press

Philadelphia

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 2/48

_

.. _-

Biblical quotations from the Revi d Bible, copyrighted 1946 and 19S/

eStand~r? Version of the

Ed uc at ion o f th e N t l 1 by the Division of Christian permission, a iona Council of Churches, are used by

Copyright © 1969 by Fortress Press

All rights reserved No art of hiduced, stored in a c'err' Pit is publication may be repro-

by any means, electronic. mechan or transmitted in any form or

or otherwise, without th e c~amcal, p.h~tocopying, recording,owner. pnor permission of the copyright

L" bI rary of Congress Catalog Card No. 71-81526

ISBN 0 -8006-0180-7

Second Printing 1970

Third Printing 1971

Fourth Printing 1973

Fifth Printing 1975

Sixth Printing 1977

6468B77 Printed in U.S.A.

Editor's Foreword

In New Testament scholarship insights, concerns, and

positions may not change as much or as fast as they do in thenatural sciences. But over the years they do change, and change a great deal, and they are changing with increasingrapidity. At an earlier period in the history of New Testamentscholarship the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke)were thought to be relatively uncomplicated documents whichhad been put together without careful planning and which

told a rather straightforward story. Today the Synopties areunderstood to be enormously intricate products containingsubtle and ingenious literary patterns and highly developed

theological interpretations. The three volumes in this seriesdeal. respectively with literary criticism, form criticism, and redaction criticism, and their purpose is to disclose somethingof the process whereby these disciplines have gained an en-larged understanding of the complex historical, literary, and

theological factors which lie both behind and within the Syn-optic Gospels. The volumes on form and redaction criticismwill deal exclusively with the Synoptic Gospels, while the oneon literary criticism will deal selectively with all the areas of

the New Testament.Literary criticism has traditionally concerned itself with v

suc1imatters as the authorship of the various New Testament books, the possible composite nature of a given work, and the

identity and extent of sources which may lie behind a certaindocument. More recently, however, biblical scholars have

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 3/48

i

FOREWOlUJ

~n paying a.ttention to the criticism of fiction and poetryan to aesthetics and philosophy of Ian Thliterary itici f th guage. erefore thean ' en .C1Sm0, e New Testament has begun to reflect

f mt~est ~ ~uestions such as the relationship of content toorm, e .SIgnificance of structure or form for meanin and

e:::,at:.ac

;? ;~ lanrage to direct thought and to moll'exis-

b .~. e vo ume on literary criticism in this series will

dis s,ensl,ltiveto both the older and the newer aspects of theC lp me.

The pUi'J.'Ose,of form criticism has been to get behind th

~;t;;'fs w~ch lite~ary criticism might identify and to describ:

on or ~as f appenmg as the tradition about Jesus was handed

munityay /om pe~?~ to person and from community to com-. orm criticism has b~s eciall .

,,/ Jhe modific.ations which the !if ~,With both Jewish::(;hristian and--

e. and ~ o~ ht of the ~ur ch-

into the tra4itim> and forr!ent?~-C nstian- ~ve introduc d for distinguishin ' th cntics have worked out cri teria

the concerns of ~ o~e s~a~ in the Gospels which reflectthought to b e c urc om the stratum that might be

that the ch~~h'::t~ I~e historical Jesus. Ithas been shown

on the content of the I: ';::~ OnI~exerted a creative influencecharacteristics makin . a ?n ut also contributed formalterial in the S' 0 ti g It possible to classify much of the ma-

cism has con:m~ ~ according to ~te~ary form. Form eriti-

.>vidual units-stories :~f lar.gely ~Ith mvestigating the indioRedaction cr'" n say-mgs-m the Synoptic Gospels.

tohave 'b~l; the , ,?ost recent of the three disciplines

out of form criticism -::;s~~ous method of inquiry. Itgrew

procedures of the earlie di I. resuPP?ses and continues the

sifying certain of th rThlScl p me ';hile extending and inten-

allem. e redaction iti .

v' sm er units-both' I cn c mvestigat~howtion o r from Writt~lffiP e and composite-frQ!!! the oral tradl-

- _I -~ources w~re put tozeth f -comp exes, and he is es ;:il-;---~~! JlLQrmJlIrger the-GOsPels as fini~ Cl~ y mterested. in the f'?!illation of

cemed with the . t p~cts. Redaction criticism is con-d 1 m erac tlon betw een an . h . d

an a at er interp retive pO int of . mente tradi tion

.Istand why the items from the trad;e~Its goals are to under·V . !1e. ctedas the}' were to' d' n were modified and con-

w ere at work ~ , osin I e~nZ t h~ogi Cal motifs that p g a finished pe~an --=-:-.. 'd I, WIG I.U elUCl ate

vi --------..

FOREWORD

the ~calpoint of vi'O.wwhich is expressed in and through

the composition. Although redaction criticism has been most

closely associated with the Gospels, there is no reason why it

could not be used-and actually it is being used-to illuminate

the relationship between tradition and interpretation inother

New Testament books.While each of the volumes in this series deals separately

and focally with one of the methods of critical inquiry, each

author is also aware of the other two methods. It has seemed

wise to treat each of the three kinds of criticism separately for

the purposes of definition, analysis, and clarification, but it

should be quite clear that in actual practice the three are

normally used together. They are not really separable. A New

Testament scholar, in interpreting any book or shorter text or

motif, would allow all three of the critical disciplines to con-

tribute to his interpretation. An effort to demonstrate thisinseparability might be made by taking a brief look at Mark

2:18-20:"Now John's disciples and the Pharisees were fasting: and people came

and said to him, "Why do John's disciples and the disciples of the Phari-sees fast. but your disciples do not Iest]" "And Jesus said to them, "Can

the wedding guests fast while the bridegroom is with them? As long asthey have the bridegroom with them, they cannot fast. "The days willcome, when the bridegroom is taken away from them, and then they willfast inthat day.

This passage appears not only in Mark but is also a part of

that substantial portion of Mark which serves as a source for

Matthew and Luke (of. Matt. 9:14-15; Luke 5:$3-35) (liter-

ary criticism). Its outstanding formal features are a brief nar-

rative (18) that provides a setting for a saying of Jesus (19a)which takes the form of a question and which is the real inter-

est of the passage (form criticism). The question of fasting

and the use of wedding imagery suggest a Jewish point of

origin. At the same time we see a break with fasting and the

attribution of joyful siguificance to the present-today is a wed-

ding-rather than waiting for the foture. These features sug-

gest a modification of the Jewish setting. On the other hand,

there is nothing, at least in I8-19a, which expresses the

church's faith inJesus' resurrection or the theological interpre-

tation of Jesus' mission which grew out of that faith. This

oii

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 4/48

,

,

r

II

FOREWORD

particular relationship to Judaism, on the one hand, and to

distinctly Christian theology, on the other, gives to 18--19a a

good claim to reflect the situation of the historical Jesus. How-

ever, 20 (and perhaps 19b) seems to grow out of a setting

later than Jesus' own. Here we see the church basing the prac-

tice of fasting on Jesus' death (form criticism).

Our text is included in a collection of stories all of which

present Jesus in conflict with the Jewish authorities (2:1-3:6)

and which are concluded by the statement that Jesus' enemies

took counsel how they might destroy him. Mark may have

found the stories already collected, and a predecessor may also

have added the concluding statement. But we do not know

why the predecessor might have added it, while we can im-

agine why Mark would have. Jesus death was very important

for him; and it assumes a prominent place in his Gospel (re-daction criticism).

If we might call the form of the Gospel as a whole a comedy

which overcomes tragedy-the defeat of death by resurrec-tion-we may then grasp the significance of our brief passage

in that larger pattern. The slight allusion to Jesus' death an-

ticipates the more direct hint in 3:6, which in turn prepares

for the definite predictions of Jesus' death which begin at 8:31,

predictions which are fulfilled in the final chapters of the Gos-

pel. At the same time the resurrection is anticipated by the

theme of the joyousness of today, which is further deepened

by the note of irrepressible newness that appears in 2:21-22

(literary criticism). Our short text contributes to Mark's presen-

tation of the reasons for Jesus' death-he challenged the estab-

lished religious order-and Mark's understanding of the sig-

nificance of Jesus' death and resurrection-a new, festal dayhas dawned offering to man freedom from compulsive ritual-ism (redaction and literary criticism).

It is hoped that the three volumes in this series will give to

the interested layman new insight into how bihlical criticism

has illuminated the nature and meaning of the New Testament.

DAN O. VIA, J R .University of Virginia

Conten ts

CH AP TE R

•

1L THE ORIGI!§..QI[.FOll~LS::!,,!,CIS.M ~.

The Necessity for the Discipline: Developments ill 3

Source Criticism and Ieife ot [esus ~es,earchd' .. £The' Possibi ity""fOrthe Discipline: Q!!cl<~ls Stu y.o ,

Th!-E~gelndt~W~;k 'h ,'N'e~~i~~;~;;'t·F~~·.C~ti~~~~

e ar les .........'_'.

-~--- DmEUUs AND BULTMANNIT THE DISCIPLINE~~ .• _ __, .

Presuppositions .. F d Their Sitz im Leben ..LIterary orms an ....-_._

Form Criticism and the Ure of l'!i\'~.•............

III EARLY SCHOLARLY EVALUATION AND USE OF FORM 38

CRITICISM 38

Continued Use of Source Analysis Alone 40

Challenges to Form Criticism 45

Cautiou s Use of Form Critici sm ~.~f'F~~ T~y of~s.: ..A. .l1J;odu~~~ . ~::-::-:- -51

CritiCISm .

~ CuRRENT QUEST FOR TIIE

IV FORM CRITICISM AND THE 57

TheofoIS~~::'~J:;~:ori,;.i 'D~~~i~~;';~~~'i,;fl~~~clr;ggt .......... 58the Current Quest .

d M thod of ContemporaryPresuppositions an e .

Scholars ':. .

f th A lication of Form CntiClSm .Examples 0 e pp 1

GLOSSARY.....................................

.............ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ••••••.•••.••••80

6

y3

67

7

'"

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 5/48

'"

Preface

'This book is intended through the written Gos eI b to be a guided tour-a tour

course of the tour you wEI s:e ~ck to the earthly Jesus. In the

~om an oral stage in the earli oWd the Gospel tradition passed

tine to its written sta e in est ays of the church in Pales-learn how the Gospels g b Our canonical Gospels. You will

and teachings of the earthl e used historically to study the life

?f the ~adition in its pred;e!~US' Fo~ criticism, the studyinthe historrcal study and tho ry stage, IS an important toolthe d is . lin ' IS volume ill'Clp e of form criti . w mtroduce you to

I should lik cism,d e to express ap "

epartment of religion of F!recIation. to my colleagues in the

b

ofSOmeteaching duties in rdman Uruversity for relieving meook I Or er to ziv .

.' am also gratefu l t c- e me time to write thisUruversity for a grant to d ? the administration of Furman

preparation of the e ray the expenses involved' thmanuscript. in e

EDGAR V. McKNIGHT

I

T h e O r i g in s o f F o r m C r it i c i s m

A cursory glance at the Gospels could lead to the con-

clusion that it is a fairly easy task to write a full and accurate

account of the life and teaching of Jesus. After all, there are

four accounts in the New Testament. Two of the accounts

(~ew and-John) bear the names of disciples who had been with Jesus and who (it is thought) doubtless gave com-

plete, accurate reports of their experiences! Even the other

two, according to tradition, are directly dependent upon earlier

aorts (Mark dependent upon Peter and Luke upon Paul}.''l'we task is simply to arrange the materials of the Gospels into

a unified story, a harmony. 'The Christian also brings to his

reading of the Gospels a concept of Jesus from his religious

tradition; the church's proclamation of Jesus Christ as Lord

and the carefully developed doctrines of the church naturally

influence the concept of Jesus gained in a reading of the

Gospels.

~

The jask (assuming the authorship of the Gospels by eye-witnesses and the authority of the church) is to o~anize the

. material of the Gos els into one h~ous account and to

paraphrase, " 'P I '! ! ! ! , -;;;;d :Fl'ly"'"the materi;I;To; the benefitof'tIfu-raith£ul. This was basically the method of the ancients.

The title of one of the most important harmonies, that by the

Reformed theologian Andre~ander .i!'~e si~nth century,~!."etho<Luseg;...Q.rmiIjiiULLatinS;Qspd_.HaTJ1l0ny .

1All four o f t h e Gospels were actually written anonymously. Later tra-

dition, which mayor may not have a basis infact, has assigried names toeach of the Gospels.

1

/"

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 6/48

=

THE ORIGINS OF FORM CRITICISM

In Four Books, in Which the Gospel Story Is Combined Accord-

ing to the Four Evangelists in Such a Way that No Word of

Any One of Them Is Omitted, No Foreign Word Added, the

Order of None of Them Is Disturbed, and Nothing Is Dis-

placed, in Which, However, the Whole Is Marked by Letters

and Signs Which Permit One to See at a First Glance thePoints Peculiar to Each Evangelist, Those Which He Has in

Common with the Others, and with Wilich of Them.

The hannonizing of the Gospels and the interpretation of"

the resultant story of Jesus in prose, poetry, and drama con-

tinued into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries-and con-

tinue among many Christians today-and the values of such a

limited approach must not be ignored. Although there are

values which derive from the precritical approach to the

Gospels and to the life of Jesus, it is impossible for a student

who is acquainted with the true nature of the Gospels and

their witness to Jesus Christ to follow this method. The Gos-

pels are not biographies of Jesus written for historical pur- poses by the original diSciples of Jesus; rather, thoe)( J"~

Iigious writings prod_,!~a-gerrerati"n..after the earthly [esus

to serve the lif1!""1illilfaith of th!C,.e,urIXchurch. However, the

, Gospels are basea on earlier oJ:aLand"Written sources and

metiioaS ave been dev;loped for m-;;vingth';ugh the ~adi-tion of the Gospels to the earthly Jesus. \J ,

This volume is concerned with form criticism, a c!iffiipliI1e~

~'i.Y.elD.pJd in the_hye~_century--aQd,..J!cl.11031edged by

schQI;m;J? be a n~!Z~an: ~,h~~plul methOd Qf dealing with

the Gos el_~.:'~rl!ls. Even an evangelical scholar who is the product of the American fundamentalism of the 1920's ac-

knowledges that form criticism contains "certain Jla!id.rl,!!!!lcn.\(and "has thrown considerable light On then-ature of the Gos-

pels and th~ ~aditions they employ. Evangelical scholars

should be Willing to accept the light."' A representative of

one of the larger popular Christian denominations in America

sa~ ~hat form criticism is as much an improvement on SOurce

~~clsm as SOurce criticism was an improvement Over the tra~

ditional patterns of literalism. "It is difficult to overestimate

~rge Eldon Lodd, The New Testament d C (G d Rapids: Eerdmans, 1967), Pp. 148, 16!l-{l9. an rlt /clsm ran

2

" 0

/"

1lIE NECESSITY FOR THE DISCIPLINE .

. f itical method." 'Y : D, Daviesthe importance of this orm-cn . d that all serious students

well says that "it)ihould..hILrecogmz: to_sQIlle' extent F : . o r mof the NeYL.!es~@!.. l!1s!!!Y_llI- 10 ments in the study

~". This chter

:ac:c~:e~:~~taied the development'01 Jesus and the ospe w h th ethod first came to beof form criticism and shows ow e m

applied to the New Testament.

THE NEC ES SITY fOR THE DISC IPL INE;DEVELOPMENTS IN SOURCE C RITICISM

A ND LIfE O f J ESU S RESEA RCH

. d lopment of twentiethThe method of form criticism. IS a eve

oback to the earliest

century scholarship, but its beg:tfe glife of Jesus. Simply

Ciiiical studies of the Gospels. d the development of /o h th ntury w ttnesse V

stated, the elg teen ce. us su lementing the tra-

a critical appro~ch to the ~~t~~e~h~rch:~d the nineteenth

ditional dogmatiC apP,?a':t.e understanding of the nature and

century saw a growth in I real sources for a study of literary relationships of thle °TnhY rce criticism of the nine-

h . I Gospe s. e sou . . .Jesus-t e canomca d th way for t he for m crltt cismteenth century thus prepare e

of the twen tieth ce nt~ry. . . d of J esus w as don e b y

~ J!.l!t .s~~~mall~ c::~ 1~~J;:768 );--who stressed"TheHermann Samuel Relm ~~ . t the dogma of the church

CI:ilms-OJ:rationarreligion o~er agam~ not approach Jesus fr o mand emphasized that a stu eh?tmU

ts hisrn but from the Jewish

. f the chure s ca ec did the perspective 0 d R eimarus however,world of thought of Jesus' OWD

d d'daY'ot publish ;ny of his four-

. 11' ecretan in .his work virtua y ills- tpt ' The work of Beimar-

h dwritten manuscn . ., f

thousan d-page, an "I e" rather than a beg mnmg0

us must be considered a Pililo~ for the ideas of Reimarus

the critical study of the earthY Jes,::; which followed. Yet the

did not directly influencef

ef

wROllll~arus were at work in thek ·thlieo eforces at wor ill e

f Rdisc_,lngthe Teaching qf 1- by

'5. A. pNe " : ' " ~ n T ; ; : e t : : . ' t e ~ I Y RevieW N , 28(~~j';':~'(Garden City:Norma n emn" I " i t at i on t o the ew

'W . D . DaVies, nt' k of ReiJnams

Doubleday, 19.66)'. p. ~\even "Fragments"/!7 !F 8 T h ~largest of the

an~Y;~u~;SSi~gaIj~~m~t~eeetej~7~ ~~jnet' J1i~ger)was pubUsbed"Fragments (Vboo°nk ':'" 1778.Jeparately as a 1D

8

< /

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 7/48

<,

I/

THE ORIGINS OF FORM CRITICISM

life and thought of others in the eighteenth century who pio-

neered in the historical study of Jesus and who did influence

the ~ter developments in the study. These early rationalists

continued to be influenced greatly by their relatively uncritical

methodology and limited by the lack of an understanding of

~e n~ture and interrelationships of the Gospels. Yet, as ahistonan of the early studies of the life of Jesus says,

We must not be unjust to these writers. What they aimed atwas to bnng Jesus near to their own time, and in so doing they

became the 'plOneers.of the historical studies of His life. The de-fects of their ,,:ork ill regard to aesthetic feeling and historicalgra~pelire out~el.ghed by the attractiveness of the purposeful un-P~Ju ced ~illg which here awakens, stretches itself and be-gillS to move WIth freedom.' '

In the eighteenth century then there was a' ." n Increasmgope~.ess~ reas?n in biblic:tLstudy; in the nineteentliCentury

~ttenlIon was gIVen to the relative merits of-the first three

ospels (the Synoptic Gospels), on the one hand and the

JFourth GospeU.12illl.), on the other, for a study of the life of

esus, to the exact literary relationships between the first three

Gospels, to the sources of the materials in these Gospels and

% re~~d qfuetlstio~which bear on the nse of these Gosp~1s ine s y 0 re life and teachings of Jesns.

coWhe~ a pres~ntation of the life of Jesus is attempted bynnecting ~eCtions of_truWoJIl'_Gospels into a "harmon »•, . . l it

~;;::~~~~~e:dthat the G:spel of John has a .9~te di~~e;,~fl t thr -Go---1s ~a l ca r amewor k f rom tha t of the

rs ee spe Inthe acco ti th S-

~o~:~umey to Jerusalem,u:ut: J:m0~~~!~s:tm~~:

visit of JesusGt:liJleeet°alJe~salthem (2:13; 5:1; 7:10). The finalrus em ill e Synopti . f a week, but in John it co . cs continues or about

(7:2) to the Passover of J=,e~ f r o : abFeast of Tabernacles

Synoptics inlply that Jesus' entiree~., .atry0ulthalf a year. The

a year, but John's account de d lIDS • ~ts no more thanyears. If an attcm t . man s a ministry of over two

Fourth Gospel as . : e l l: ' :d~o thfollowthe account of the• e tree Gospels it becomes aAlbert SchWeitzer The Q u < 1 .It

of its Progress from'Reimor t o f.J .,h e f/storlcal Jesus: A Critical StudyEofn~f~bHed.; London: Black " \910) re e

2 ,9 tra(n

H,·w. Montgomery(2nd

...... i8torlctlI Jesus.)' ,p" ereafter cited as Quen

4

THE NECESSITY FOR THE DISCIFLINE

matter of putting the material of the Synoptics into a Johan- lnine framework. This was the basic procedure followed by

e ear y writers on the life of Jesus. But such a use of the

J,Eospel of John in the study of Jesus' life was questioned by

'){~. F. Strauss in his Life o f Jesus (183~6).' He pointed out

that the Johannine presentation of Jesus is clearly apologetic

and dogmatic, and that it shows an even further develop-ment of tendencies seen already in the Synoptic Gospels. He

asserted, therefore, that the nature of the Gospel of John makes

it unsuitable as a source for the historical understanding of

Jesus. This point was reinforced by later studies, especially

y the work of F. C. Baur, and scholarly investigation began

to focus on the Synoptic Gospels as sources.That there are literary relationships between the Synoptic

Gospels was noted long before the nineteenth century. A'/

great number of narratives and discourses exist in more than

one of the Gospels-frequently in all three-and the agreements

extend beyond subject matter to the details of style and lan-

guage. Compare the three accounts of the parable of the mus-

tard seed:

Mark 4:30-32

And he said. "Withwhat can we com-

pare the kingdom of God. or what para-

ble shall we use for it? Itis like a graino f musta rd seed,

which, when sownupon the ground, is

the smallest of allthe seeds on earth;

yet when it is sownit grows up and be-comes the greatestof all shrubs, and

puts forth large branches, so that the birds of the air canmake nests in itsshade."

'David Friedrich Strauss, The Life 01 le..... traDS. Georgo Eliot (2

vols., London: Chapman Bros., 1846).

Matt. 13:31--J2

Another parablehe put before them,saying, "The king-dom of heaven is likea grain of mustard seed which a mantook and sowed inhis field; it is thesmallest of all seeds,

but when it hasgrown it is the great-est of shrubs and be-comes a tree, so that

the birds of the air

come and make nests

in its branches,"

Luke 13: 18-19

He said therefore,"What is the king-dom of God like?And to what shall Icompare it? Itis likea grain of mustard seed which a man

took and sowed in hisgarden; and it grewand became a tree,

and the birds of theair made nests in its

branches."

5

/

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 8/48

c I' THE ORIGINS OF FORM CRITICISM

- ~ Augustine (354-430), bishop of Hippo, was the first to con-

sider seri~usly the literary relationships among the Gospels.

He explained the relationships by the judgment that the Oos-

pels originated in the sequence, Matthew, Mark, Luke, John,

and that the later Gospel writers had knowledge of the earlier

Gospels. Matthew is the earliest Gospel; Mark is an abridg-

me~t of Matthew; and the later Gospels depend upon theseearhe~ ones. Although other theories were put forward to

expla~ the ObVIOUSliterary relations of the Gospels, prior to

the nrneteenth century the view of Augustine was the "ortho-

dox" position. Even Strauss held this position in his Life o f Jes us.

. In the nineteenth century, however, a quite different solu-

c~ tion to the Synoptic problem was reached by students of the

c Gospels: Mark ~ earliest of the canon!,caI.Gospels. The

authors oiliramiew and Ll!e J ia <Ir;;ra j. hefore them' ... they

wrote, and, therefore, the~ls ..£llmmonJILaJl three Cos-

cg;S~es.Ult fronwb~ J,lSe_w)Jic!)_Ml'tth.!<wand Luke made of

ar . Matthew and Luke also ~s2ianother source, now lost., IS non-Maroun source (calle~presumably an abbrevia-

tion of the German word for "source," QueUe) accounts for

the non-Marean materials common to Matthew and Luke.

Fmally, each used additional material which was not used by the other.

}.Karl Lach!"ann, best known for his work on the Greek text

,of the New Testament;seems.:;to have been the first SCholar to sUl?nnrtthe iority f ;{';~ k' f f -,'" pnon O'lVIar rom a careful study -oLtheacts. ,In 1835he showed t a , when Matthew and Luke used

m~eza~ also found in Mark, the order of events in Matthew

~n ~ e corresponds closely, but that no such corrcspon-

eh~ceh~ order f

exists when Matthew and Luke use materialw IC IS not ound in ark L hMatth d L k . ac mann, presupposing thatall thr":San ~ e could no have used Matk..CQncluded that

but that J:?~~I~~~els used an er Wri:te'1.•. D r ora(sour~the order of events 10 the older source

~ore athccuratde!~than did Matthew or Luke. Mark thereforegIves e tra ition of th G ls .----!---'

otli G ls .- e oSp'e at an earlier stage than theer ospe. - __ . _ '"'"-- . _ . . . "-

' Kar l L ach ma nn , " De Or dln .Theologische Studien und Kr't'k e naSrraloonumIn evangelils synoplicls·

" en, (1835),570 If. '

6

THE NECESSITY FOR THE DISCIPLINE

Of course, even the schola world was slow in accepting

the ideas of the nanty of Mark and the use by Matthew

and Luke of Mar an ana ier source. This totally reversed

the traditional view of Synoptic relationships. But by the end

of the nineteenth century it had come to be looked upon as an

assured result of the critical study of the Gospels. For the next

quarter of a century, scholars were mainly occupied ,withadditional documentary study-the attempt to trace and Iden-

tify all of the various written documents beyond the Synoptic

Gospels. Influential in the documentary quest was the pre-

supposition that a history of Jesus would result. Scholars felt

that, once all the documents had been isolated, their contents

worked out, and their relation to the Synoptic Gospels deter-

mined, a scientific history of Jesus could be written.

A high point in the documentary study of the Gospels came

in B. H. S,!reeteiLI!!.e.. • .fO'E:. GO!T!.eJ 3;_A..J ! '! d .Y .. ..o t O rig!!!'..(1924).- He gathered up the results of the study of.the. G os-

pels in a systematic, comprehensiye_1V'l.}'.His most original

contribution was the theory of the use of four documents inthe origin of the Gospels. In addition to Mark_!!Jld Q (the

designation of the non-Marean material common to Matthew

and Luke), Streeter suggest;d that Matthew ~nd !::':l<e_had

documents peculiar to each which <;2l11d bi,ciiIfed M an:\LL.

The supposition that the earliest documents, particularly

Mark, carry us back directly to the earthly Jesus was shaken

even before Streeter did his work. The studies of Wilhelm

Wrede, Albert Schweitzer, Johannes Weiss, and Julius Well-

hausen established the fact that Mark was not a SImple, un-

complicated presentation of the life of the earthly Jesus. It

cannot be presupposed that even the earliest documents carry

us back directly t~ Jesus himself. .'@elm W!e~.in..".u~r~te<Lt!'is~w tu;..r!10th~ mterpre;

tation ciIthe Gospels by Ius work on the Messianic Secret.

He dealt most fully withtlle.t~k'),nd in~cated

that in the Gospel of Mark there are not only istorica but

also, and more important, ogmaticide'aS) The histoncal pat-

tern of the events in Mark is gIven y rede: Jesus appeared

as a teacher in Galilee surrounded by a circle of disciples with

'Burnett Hillman Streeter, The FOUT Gaspel.r, A Sludu o f Origins

(TOV. ed.; London: Macmillan, 1930).

7

./

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 9/48

THE ORiGINS OF FORM CRn1CISM

whom he traveled and to whom he gave instruction. Besides

teaching, Jesus is also pictured as performing miracles, espe-

cially the exorcism of demons. He associates with publicans

and sinners and takes up an attitude of freedom in relation

to the law. He encounters the opposition of the Pharisees and

the Jewish authorities, who set traps for him and eventually,

with the help of the Romans, bring about his death.PBut there is also a definite nonhistorical dggmatic_CQntent

~ Mark in whiclr esus ISpresente_d in sU!1emat.!!!ili~'%) He

IS the bearer of a speCIal messianic office to which he is ap-

pointed by God. The real fact, according to Wrede, is that

before the resurrection no one supposed that Jesus was the

!'1essiah. But :uter ~e resurrection there was a tendency to

mterpret Jesus mInIstry in messianic terms. The Gospel of

Mark, therefore, attempts to give a messianic form to the non-

messianic earthly life of Jesus, The tradi tion of the non- mes-

~ianic character of Jesus' life was so strong, however, that the

impulse to interpret Jesus messianically was not able to do

away with the historical elements. Hence, the historical and dogmatic elements had to be harmonized.

Wrede claims that the historical and dogmatic conceptions

~e h~onized in the Gospel of Mark by means of an idea of

intentional secrecy. Jesus is represented by the writer of Mark

(so Wrede says) as keeping his MessiahshiE an almost com-

P.l!'~i1e he is !Jl-ell!:!h,-He does ;~veal himseJiii),!essi"ili to,ru,s-dlScir.lc:sb~t he ;,imams'Uiifutelligible-eveIi to

~em, and It ISonly WIth hISresurrection that the true percep-

tion ?f what he is begins. Attention is called to Significant

data mthe Gospel of Mark which support this theory. In the

Gospel of Mark the demons who seek to make the identity

?f Jesus known are silenced (Mark 1:25, 34; 3:11-12). SecrecyIS commanded after same of Jesus' mighty works have been

a~compllShed (1:44; 5:43; 7:36; 8:26). After the confession

o. Peter ~d. at the descent from the Mount of Transfigura-

tion ~e disciples are charged to tell no one that Jesus is the

Messiah (8:30; 9:9). Jesus withdraws from the multitudes'

he embarks upon secret travels and moves around Galilee un-

"WillIam Wredgen: Vondenboeck'.?n'd w.:..wsgehelmnb In. den Eoongelien (GOttIn-Ruprecht, 1963), p. 130. precht, 1901; reISSued, Vandenhoeck nnd

8

THE NECESSITY FOR THE DISCIPLINE

known (7:24; 9:30). He instructs the disciples privately eon-

cerning "the secret of the kingdom of God" and other subjects(4:W-12; 7:17-23; 8:31; 9:28-29; 31, 33-35; 10:33--34; 13:3-37). L

Scholars following Wrede have not unanimously followed

his theory of the "Messianic Secret" as a means of harmonizing

the historical and theological inMark, b~~~reinf!,~d

his view that Mark was not merel a historical resentatioof. the earthly Jesus. A I ert Schweitzer's work. on the, life of

Jesus, published the same year that Wrede pubh~hed hISwork~reinforced Wrede's view that Mark is not mere hlstory.!' Mark,

indeed~isJl)ade_up-oJ a number of in<!!p'en~ent units and .

n~£!osely connected hjstor~-'!Ln::urative at all. Suggestive

analogies'areusedio express this view:

The material with which ithas hitherto been usual to solder thesections [of Mark] together into a life of Jesus will not stand thetemperature test Exposed to the cold air of critical skepticism it

cracks· when the"furnace of eschatology is heated to a certain point

the soiderings melt. in both cases the sections ~llfall apart. .

Formerly it was possible to .book through,~lickets . . . whichenabled those travelling illthe Interests of Life-of-jesus construc-tion to use express trains, thus avoiding the inconvenience o~ hav-

ing to stop at every little station, chang~, and run the nsk ~f missing their connexion. This ticket office IS now closed. There IS

a station at the end of each section of the narrative, and the con-

nexions are not guaranteed.12

The works of ohannes Weiss~'!..-and....Juli!!!!. We1J!1ause~::V'.

served to stren en the view that Mark is not, mere histo~

and to call attention to the activit)' of the early Christian

community b"the fomJation-of Mark. ..By the early part of the twentieth century the .cDtical: . r u dy

of the Synoptic Gospels had arrived at the followmg posittons:

(1) The "two document" hypothesis.-was acc~£te~ ~ark \l.D~. \//

Q served as sources-for Matthew and LUlie. (2.)...Both Mark .../fi';'"d Q , as well as Matthew and Luke, were influenced by the

----...... ~_.-

"Albert Schweitzer, The M ystery o f the King d om o f qod: The SeC1'~

of /eS1J8' Messiahship and Passion, trans. Walter Lowne (New York.Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1914). 331--32

"Schweitzer Quest o f the Historical/estIS, pp. . V denhoeck "johannes Weiss, Das iilteste Evangelium (COttingen: an

nod'Ruprecht, 1903). E I' Marel (Berlin' Reimer) wasuJulius Wellhausen Das v ange lurn l a r i e e l

published in1903, ";d in the next five years oommen es appear on Matthew, Luke, and John.

9

'" /

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 10/48

'"TIlE ORIGINS OF FORM CRITICISM

~

' !h~ot()giSalviews of the early church. (3 )__~~rk.A!'_d_~ con-

-:: ,~-ta!!.l~!Lnotonly early authentic mat~ri~sbut also materials_of

- later d~e. Therefore, the discipline of source criticism did

~6ot bring scholars to pur~ historical sources which allowed

them to arrrve at an unbiased primitive view of the earthly

Jesus. Some other tool was necessary! But what tool could

be used to pry beyond Mark and Q into the preliterary stage

of the Synoptic Gospels?

THE PO SS IBILITY FOR THE DISC IPL INE,

GUNKEL'S STUDY

O F LE GE ND S

A s,tudyof the early oral stages of a literature known to us

only 10a l.ater wntten form sounds like an impossibility I But

the truth IS that studies had been undertaken which would

enable .scholars to pry back into the preliterary stages of the

Synoptic Gospels. The scholar who made the greatest direct

~ c?ntnbution by showing the actual possibility of fonn criti-

- - :4 \ ~Ism.was lk!rpann Gunkel, an Old TestJ,menLscholar..-He-iphed-form eritieism to the first book of tbJ'JliblJ'J G~esis.

he fu:st.fhle.lJ09ks_Qfthe .Old.Testament (kno\m.colkcti';;;lyas the Pentateuch) 11I . ~-

-_ -7 ..~ para e 10many ways the Gospels of the

1 L ( e~esJa!!leAt. Although tradition attributes them to ~es

as tradition attributes the Gospels to the apostles), a care-

ful study of the materials indicates that they assumed their

Pdresentform over a long period of time and that a number of '; - ocuments no longer exta t d ,f' of th bo c ks n , were use in the composition

r ; o , ! : ; - . ~ " " ) hIe hood' ~efore the end of the nineteenth century'"'jl.,.t sc 0ar s a arrived t" d" '

,J ."I' /i" ' sources The d a h assure results concerning these~" ~ '" < R to the . e ' d o~u;;:ents, owever, did not carry scholars back

~ "r '~ --: ;" t-' Pentat p no 0 e events recounted in the books of the~,if ;~1- b euch, Some tool besides source criticism was seen to

{11,~~,< ; . " , G:::;::s;,ary to go behind the earliest documents, Hermann

t.~~.:,~~~that tooLas the Old Testament scholar who developed just

l .4 ...1 ; . ~ { . 11

v < . - . . . . , Gunkel acknowledg d th I"r,{~l,.$ Genesis (and the oth e - ''j resi; ts of source..criticism; that"'~ previo d er books of the Pentateuch) grew out of Ie - ~t~o,:"ments which may be attributed to the Yahwist.

of th-~h:th century B.C., the Elohist (E) of the first half ~~g __ century,-and the Priestly writer (1') between.. ~

10

THE POSSIBn.ITY FOR THE DISCIPLINE

500 ~,!±,. The documents were combined and edited by

laID writers to form our present books: J and E were united

near the time of the end of the kingdom of Judall (587); and

this combined work,-lE, was united with P about the time

of Ezra (444). Before the-doc~;ments were written, however,

there were individual stories which originally existed in an

oral form and which only later were placed in a structured

collection. In order to study the early history of the stories

they must be studied as individual units, not as they nOW

stand in the Book of Genesis, Gunkel's view of the nature of

the earliest documents assisted him in his work, for the earliest

documents were not literary works composed by authors. The

Yahwist and the Elohist were collectors, not authors; and al-

though the Priestly writer maynave"been a -geiiiime-author

responsible for a literary creation, he too used previous ma-

terials which can be isolated and stndied as independent

stories. Gunkel saw these originally oral stories as being de-

veloped and modified within the life of Israel over a long pe-riod of time. As some of the stories were carried into Israel

from foreign countries and as all of the stories traveled into

different parts of Israel, they were adapted to the existing

life of the people. The stories also changed as they were

transmitted from one age to a succeeding age. "When a new

generation has come, when the outward conditions are changed

or the thoughts of men have altered, whether it be in religion

or ethical ideals or aesthetic taste, the popular legend can-

not permanently remain the same. Slowly and hesitatingly,

always at a certain distance behind, the legends follow the

general changes in conditions, some more, others less."'·

Gunkel classified the stories of Genesis in light of the pur- poses of the stories. He acknowledged that some legends are

"historical" in that they reflect historical occurrences, they

contain the remnant of a tradition of some actual event. But

he emphasized that legends in general arose in Israel for the

purpose of explaining something and he classified several dif-

ferent types of legends on the basis of what it is that they ex-

"Hermann Gunkel, The Legends of Genesis: T11e Biblical Saga and History, trans. W. H. Carruth (New York: Scho~kent H)~4), pp. 98-9~.The Legends of Genesis is a translation of the Introduction to GunkehCenesU (COllingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1901) •

11

/

/"

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 11/48

TIili OHIGINS OF FORM ClUTICISM

plain: ethnological legends, etymological legends, ceremonial

,legends, and geological legends.

~_EJ!1_Il.?l£gicai~gen~ are fictitious stories which were de-

vised to explain the relations 2f tribes,- The story of Jacob's

deception, for example, explains how he obtained the better

country.

-¥E,tymological lege~-: resulted from the thought given by

ancient !srael to the origin and meaning, of the n~lJl~ of r~._

moun!..~, wells, sanctu:yie§..JlDcLcities. The explanation in

the legend is not scientific but popular, based on the language

as it stood. "It identifies the old name with a modem one

which sounds more or less like it, and proceeds to tell a little

story explaining why this particular word was uttered under

these circumstances and was adopted as the name."'· Jacob is

interpreted as "heelholder" ('aqebh), for example, because at

birth he held his brother by the heel.

The imp~n:ant ceremonial legends seek to explain the exis-

!ence of rehgIO~sceremonies which had come to play such an~porta?t, pa;t m Israel. ":"'~atis the origin of the Sabbath, of

circumcision, The real ongm caunot be given, so the people

tell a story to explain the sacred customs. Tbe rite of circum-

cision~for e~ample, is in memory of Moses, whose firstborn

was clfcu:nclSed as a redemption for Moses (Exod. 4:24--26).

GeolOgIcallegends explain the origin of a locality. "Whence

comes the Dead Sea with its dreadful desert? The region was

cursed by God on account of the terrible sin of its inbabitants.

Whence comes the pillar of salt with its resemblance to a

woman? That is a woman, Lot's wife, turned into a pillar of

salt as .punlShment for attempting to spy out the mystery of God (XIX 26) "17 Of

., ." course, various motifs are frequently com- bmed inone legend and some legends carmot readily be classi-fied.

Gunkel felt that the history of the legend can be derived

from a careful study of the legend itself because it shows the

result ?f changes in time and place in itself. Slight additionsextensive additions d . . ') an m rare cases an entire story have beenadded to the tr diti S I dd a mon, uc1a itions may he recognized by

the fact that they are out of place in an otherwise harmonious

"Ibid., p. 28."Ibid., p. 34.

12

/

THE EARLIEST WORK IN NEW TESTAMENT FORM CRITICISM

story and by the fact that they are relatively unconcrete. Since

the art of storytelling degenerated after the high point which

gave the legends their initial fonn, later additions show more

care for the thought than for the form of the story. Such later

additions usually contain speeches and sometimes short nar-

rative notes. The note that Jacob bought a field in Shechem

(33:18-20) and that Deborah died and was buried at Bethel

(35:8) are such narrative notes.More important than the additions are the omissions which

are intended to remove objectionahle features. Gaps in the

narrative give evidence of such omission. "Indeed, to those of

a later time often so much had become objectionable or had

lost its interest that some legends have become mere torsos."

The case of the marriage with angels and the story of Reuben

are such torsos. "In other cases only the names of the figures

of the legend have come down to us without tJ:eir legen~."'8

The names of the patriarchs Nahor, Iscah, Milcah, Phiehol,

and Ahuzzath are illustrations. The legend of the giant Nimrod

has been cut so that we have only the proverbial phrase, "like

Nimrod, a mighty hunter before the Lord" (10:9). Some

stories lost their context in transmission and were not correctly

understood by later writers. The later narra~ors, for example,

do not know why Noah's dove brought an olive leaf (8: 11) or

why [udah was afraid to give his youngest son to Tamar

(38:11).

Hence there is spread over many legends somethinglike a bluehaze which veilsthe colorsof the landscape: we often have a f~el-f ing that we indeed are still able to recall the moods of the ancle.ntlegends, but the last narrators had ceased to have a true .appreCla-tion of these moods. We must pursue all these observatiOl~s,find

the reasons that led to the transformations,and thus descnbe theinner history of the legends."

T HE E AR L IE S T WOR K iN NE W TE STA ME NT FO RM CRI TIC ISM

With tile necessity for a study of the preliterary period of

Gospel origins established by New Testament scholars ~d

the possibility for preliterary study established by Gunk~~ m

his research on Genesis, it was inevitable that the fonn cntical

"Ibid., p. 101."Ibid., pp. 101-102.

IS

, --

/'lli·.•

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 12/48

"'"=

THE ORIGINS OF FORM CRITICISM

approach would be applied to the Gospel tradition. Three

scholars are credited with beginning this new effort in the

study of the Gospels in the years 1919 through 1921. In 1919

came Der Rahmen der Ceschichte lesu. [The Framework of

the Story of Jesus] by Karl Ludwig Schmidt and Die Form-

gesehiehte des Evangeliums (English translation: From Tradi-

tlcn to Gospel, 1935) by Martin Dibelius. These were followed

in 1921 by Rudolf Bultmann's Geschichte der syooptisehen

Tradition (English translation: History of the Synoptic Tra-ition, 19(3).

_arL!::u~:~g Schmidt ..was only twenty-eight years old whene published his book. Itwas his first book and established his

reputation as a New Testament scholar. The title indicates

the concern of the book-the framework within which the

~spel writers placed the life of Jesus. As was seen earlier,

this was not a new concern. Earlier scholars such as D. F.Strauss had deal~ with this. But Schmidt did a comprehensive

study of the entire Gospel tradition and come to conclusionswhich both demanded and enabled New Testament scholars

to pry back of the Gospels into the earlier oral period.

. Schmidt accepted the conclusions of scholars as to the rela-

tions of the Synoptic Gospels-that Mark was the e!!lliest of

t!, '~ptiC ~ospels and that i f was_us d by~~;l<lttm,w~_and Lu e alo~g With ~on-Marcan materials. But he along with

~ome earher scholars saw in addition that the Gospels-Mark

IOcluded-are made up of short episodes which are linked to-

gether by a series of bridge passages which provide chronol-

ogy, ge~graphy, and a movement of the life of Jesus from hisearly ministry to his arr t Th' "" es . e passion narrative is an excep-

tion, for It rea~he~ ~omething like its present fonn at an earlydate ~nd the IOdlVldual units in the passion narrative have

meanmg .onI'I as t~ey fit into place as parts of a larger whole.

The passion narrative as a unit came into existence very early

to ~n~wer the question asked in the early period of the church's

~tlVlty, "How could Jesus have been brought to the cross by

e people who were blessed by his signs and wonders?""o

By a careful study of the tradition Schmidt concluded iliat

T':~~d~f9S=~D : . Rah~.~che' Ges<hlchtelem (Berlin: p. 305. ' ISseus""",w Buchgesellschaft,1964),

14

/

THE EARLIEST WORK IN NEW TESTAMENT FORM CRITICISM

the Marcan framework itself was.llot original tQ~.J!!GGospelj fir"

writer provided the frameJ;Yllrkin th!lJigl:lt.o£.his.o~,n..i]JL... l:!i.ts.His concluding paragraph points out that the lack of re1!!.!.!on-

ship between the units in Mm,.!~l:les.t..GQs.Pd,J;hpj](Ul>at

ilie oldest tradition of l\sus.J:\Jll,Sisted..Pi..lw abundance of

iIiividual stories which have been united by earl Ch :!stians

wiili their cnrr.;'rent reJi~us,-!!pologetic, and missionary inter-ests. "Only nOW-ana then, from considerations about the inner

&racter of a story, can we fix these somewhat more precisely

in respect to time and place/~ut as. a whole there is no life of LJesus in the sense of an evolvmg biography. no chronological

sketch of the story of Jesus, but only single stories, pericopae,

which are put into a framework."" The work of the evangelist i ./as seen in the completed Gospel is important for understand-\

ing the life and iliought of the church of his day. But for the

earlier history we are dependent upon the single episodes.z

The episodes obviously came from the Christian believers

among whom they circulated singly in oral form, They were

preserved and transmitted because they met the needs of the

church as a worshiping community .

If it is the case that the rise of the Christian faith can be under-stood only in terms of the development of Chri:tian worship-aview which has won increasingly WIde acceptanc.e .m recent years-

it is clear that the rise of Christian literary activity must also beunderstood in relation to the experience of worship. In m~ opinion.

the significance of the early Christian tradition of \~orslllP. for the

process of which the literature of the Gospels came Into being can-

not possibly be exaggerated?'

Schmidt carefully studied the entire Synoptic tradition ~om

the perspective of the framework which the Gospel wnters

gave to the life of Jesus. He also ga,:,es.o~e helpf~l suggestions

as to the nature and origin of the mdlVldual umts ma.k~ngup

the Synoptic tradition. But Schmidt did not really ulIh~e the

tools of form criticism to pry back into the oral penod of

Gospel origins. This task was left for Martin Dibelius and

Rudolf Bultmann." ' * ' DibeliYs...was. the firsUo apply ~orro critici~m .to the Sy- /

no tic tradition. Indeed tl,e term _form cnticlSm [Formge:.- - - ~ '''''

j

Mlbid., p. 317."Ibid., p. 31.

15

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 13/48

-,

==

=

THE ORIGINS OF FORM CRlTlCISM

.§Chlchte~came to be used in biblical studies because the title

of his I11I9volume was Die.J:0rmgeschlchte des Evangeli!:,ffl!.:.

Dibelius's p~~_~ explain b =reco~truction-and analy-

s~gm of th!Ltrad~pon about Jesus, and_tlius to pene-l trate into a eriod revious to that in which our Gospels and

t eir written_sources wer';; recOraed" and "to make clear the

~ illention and real interest of the earliest tradition."23

~ - Bultma~'; vollliQ«J!!~.~pl'.eare_d_in 1921, two y~ a£t~-~a.toIIJ1~,~~ witl>.Jll« ,purpose of "discovering what theoriginal units-of the synopties were, boili sa in s and stories,

(' to try to establish what their hi:;toric setting was, whether

iliey bel!!.!!g"'.d.1O' !-I1 Jlm ;m : or ~cond!l!Y tradition or whether

tliey wer':.,~ product of editorial activif:y."24 Bultmann sub-

mitted the entire Synoptic tradition to a searching analysis;

and. although Dibelius was the first of the two writers, Bult-

mann's name and method of analysis have been more closely

associated with foJ:!l1..Cl'ilieismthan has the name of Dibelius,

Because of the signiflcance of Dibelius and Bultmann in NewTestament form criticism, ilie whole of the following chapter will deal with the meiliod of these men.

"Marttn Dibelius, From Tradilion 10 Go."el trans Bertram Lee Woolf (l t ew York: Scribner's, 1935), p. iii. ' .

Rudolf Bultmann, H/.rtory of Ihe Synoplic Tradition, trans. J o h nMarsh (New York: Harper, 1963), pp. 2-3.

16

\I

T h e D i s c i p l i n e A p p l i e d b y

D i b e l i u s a n d B u l t m a n n

Form criticism has not remained static. Because o.fits

very nature it has changed as new in~ights have been g~me~

into New Testament literature and history. Yet ili~ m.odi£cad . h b . line with the initial work of Dtbelius an

tions ave een in f hBultmann: therefore knowledge and general acceptance 0 t e

work of these men is presupposed and ne~~s~ary for under-standing and using the discipline of form crittcism.

PRESUPPOSITIONS

Form criticism moves from the existing text of ~e Synoptic

Gospels to an earlier stage which does not now eXISt. In orde~

to do this certain iliings must be established or presurpose.1. ' .' and transmission of the matenals.

about we nature, ongm.

Source Criticism .

The early form crities accept and build uPd onthe cfo~~lusG'Ons

h lit interdepen ence 0 UJe os-of source criticism. Tel erary . . . W

I ld US

wiili a profitable tool for form enticlSm. e pe S provi es I' tr t d by Matthew b how Marean and Q ma~.rj,! IS ea e

:~ °L~~~e and ~e ~y ';'-;'m-;'- that ilie sa~e pri:tl~:a':~ Iwork during ilie written period were operafhve ~n M k nd

b f 't as "'ven its orm m ar ational material even e ore 1': b' I tl ~ starting point for Q 'ti°' however IS mere)' 1......

. Source en elsm, '. ..' as ilie task of f

: .,. f when form cnticlSm IS seenorm cnhclSm, or. . . the S 0 tic tradition and of

discovering the ongmal umts off ili y n . J ilie written source "(-establishing the earlier history 0 e . um "

_of any particular unit is a matter of mdiHerence. .

17

p:co

-' r . .,'.: ~ /'

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 14/48

=

TIIE DISCIPLINE APPLIED BY DIBELIUS AND BULTMANN

Independent Unit, of Tradition

The "funQ~Illental assumption," and in some sense the

assumption which makes form criticism both necessary and pos-

sible, is that the tradition consists basically of individual sayings

\

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 15/48

THE DISCIPLINE APPLIED BY DffiELillS AND BULTMANN

optic tradition. But his approach does not demand as detailed

a picture of the church as does the approach of Dibelius.

Hence Bultmann is satisfied to divide early Christianity into

two basic phases: Palestinian Christianity and HellenisticChristianity.

Classification of Form

Dibelius and Bultmann assume that the materials can be

; !classified as to fo~ and that the form enables the students to

reconstruct the history of the tradition. Dibelius says that a

careful critical reading of the Gospels shows that the Gospel

,/ writers took over unit~ial which already Eoss!'-ill'd a

~. form of their own. Dibelius is not speaking of aesthetic stan-

Sp{~\l" ~ar s"created by' a gifted. individual when he speaks of theform of a tradition. He IS speaking of the "style" of a unit-

a style or form that has been created by its use among early

Christians. The specific use to which a unit is put determines

its form, and in the case of the early church the forms devel-

oped out of primitive Christian life itself. The units, there-fore, have a fq!J!l ..l\'hich i§~~eir_ pla~ in-!h.e life

VOf the church. "':Ve are concerned ... not with things remem-

ered complete inthemselves, though without form, and thus

passed on, b.ut, from the very beginning, with recollections

ful.1 of e~otional power to bring about repentance and togam be~levers. Thus the things which were remembered

automatically took On a definite form, for it is only ~hen such

matters have received a form that they are able to bringabouL

repentance and .gain converts.'" Form criticism, then, must in-

qUlre into the life and worship of early Christianity and ask

wh~t categories are possible Or probable in this community of

unliterary people.Bultmann is in complete accord with this assumption. "The

proper undersbnding of form-criticism rests upon the judg-

~~~t that the literatu~e ... springs out of quite definite con-ns and wants of life from which grows up a quite definite

- style and quite ~pecific :orms and categories."' Every literary

.I cat~go,?, then Willhave Its own "life situation" [Sitz im Leben]which IS a typical situation in the life of the early Christiancommunity.

'JbU/., pp. 1a-14.'BultmanD, Hl#Of1I of the S f/1IO P Iic Tradillon, p. 4-

20

LITERARY FORMS AND THEm SITZ 1M LEBEN

L I TE R A RY F OR M S A N D T H EI R S ITZ 1M LEBEN

Both Dibelius aud Bultmann, following the example of a

form critical study of the Old Testament, find a variety of

forms in the Synoptic Gospels.

The Farms of Dibelius

~Jillll:9.ncero..Qf .lli!:>~liusis.with .the-narrative material ..of the Gos els, and he fin_<!~three major categories of nar.r a-tive materiafIn- addition to the Passion narrative. The PaSSiOn

';iOry 'c a m e first. ItwaS told relatively early as a connect~d

story. Then paradigms developed. These were short sto....es

which told of isolated events in the life of Jesus and which

were suitable for sermons. When pleasure in the narrative

for its own sake arose, the technique of the tale [Novelle]

developed. Also, legendary narratives gr?wing out of per-

sonal interest in the individuals involved WIth Jesus developed

and joined themselves to the periphery of the tradition.

Paradig~he sermons...2f t . h < l . ef!!'ly._Christians did notco~;simply the bare message of the gospel "but. rather

the message as explained, illustrated and supported With ref-

erences and otherwise developed.'" The narratives of the

deeds of Jesus were introduced as examples to illustrate and

support the message. These examples constitute the oldest \ .,/

Christian narrative style, and hence Dibe~ius suggests the

name "paradigm" for this category of narrative. .

The-!ribute m.,?ney (Mark 12:13-17) is a pure paradigm:

And th sent to him some of the Pharisees and some of.the He.ro-di ey him' his talk And they came and said to him,

tans, to entrap m· f . f "Teacher we know that you are true. and care or no man, fr~odu

do not re' ard the position of men, but truly teach the way 0 .

Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, or not? S.houIhdwe.dPato

yththem," len' their hypocnsy e Sal em,

or should we not? But o~g . d 'let me look at it.·

~>;!.;t ::u~h:h:n~~Sf..~I;'~ s:d Soili~~::~?seJ~u:n:~;,,~

inscription is this?" They sal~ i l i : : t or: Caes:..r's and to Go d them "Render to Caesar the gs zed t b u nthe things that are God's." And they were ama a .

The following units (with parallels in other Gospels at times)

are also judged to be pure paradigms. Mark 2:1-12, 18-22,

'Dlbelius, From TradUlon to e;"spel, p. 25.

/

"-

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 16/48

I

=

THE DISCIPUNE APPLIED BY DIBELIUS AND BULTMANN

23-28,3:1-5,20--30,31-35; 10:13-16; 12:13-11; 14:3-9. Other

less pure paradigms include: Mark 1:23-27; 2:13-11, 6:1-.Q;

10:17-22, 35-40, 46-52; 11:15-19; 12:18--23, Luke 9:51-56;

14:1--{j.

From a study of the paradigms themselves Dibelius finds

.!~ess~.ntial characteristics: (I) independence from the liter-

ary ,:,ntext, (2) firevity-:aif't s!rI)£liC:iD'~li'[trse as.examples illa sermon, (3) religious rather than artistic coloring and style~

(qr::a.@.~ctic style often causing'th~' words of J eSlls to"~and.

~ut S.l.~!!~ly,and (5) an ending in a thought useful for I'~g~s!!:w g. . :" . word or act of Jesus,01'''the reaction of the onlooke!:~

Jalf', . The tales in the Gospels are stories of Jesus' miracles

which originate in their present form not ,~rrh preachers but

WIth storytellers and teachers who related the stories from the

life of Jesus "broadly, with colour, and not without art," In-

deed, ·'1itera.':-!i4tYl",i!Lre'portin~miraelfy, a-fea~e which we

nllsse'! on the whole from. Paradigms, ... appears inthe T ,tle s -'

with a certain regularity."lO The style of the tales comparesWIth the style of similar stories from ancient to modern times:

First ~omes the history of the illness, then the technique of

~e miracle, and finally the success of the miraculous act.

'Tales belong to a.higher grade of literature than paradigms."!'

. The first tale ill Mark is the healing of a leper (Mark

1.40-45). (The miracle recounted in 1 :23-27 is a paradigm,not a tale.)

~~d a leper came to him beseeching him, and kneeling said to him,you will, ~ou can make me clean." Moved with pity, he

stretched"out hI .s hand and touched him) and said to him, "I will;

bf clean. And Immediately the leprosy left him and he was made

c edan.'dAndhhiesternly charged him, and sent h i m away at onceanswto'''S I '

hm, ee t 'at you say nothing to anyone' but go

s ow yourself to t h ' t d fI "d d e pnes . an 0 er for your cleansing what Moses

Cornman e I for a proof to the people." But he went out and be-

ga~Jo ta~ freely about it, and to spread the news, so that J e s u scod DO Ianger openly enter a town, but was out in the COWltry·

an peop e came to him from every quarter. '

'Ibid., p. 70. Hlbid., p. 82.ulbid., p.I03.

22

-

LITERARY FORMS AND THEIR srrz 1M LEBEN

Other Synoptic tales are found in the following units: Mark

4:35-41; 5:1-20, 21--43; 6:35--44, 45-52; 7:32-31; 8:22-26;

9: 14-29, Luke 1: 11-16.The tales are similar to paradigms in that they are individual I. .

stories complete in themselves." But in almost every ?ther

way they differ. The tales are much longer than paradigms,

and they contain a greater breadth of description due to story-tellers and teachers "who understand their art and who love

to exercise it."13There is also a " lack g U k . .Q Q !.i J ).n a l Q JQ tiQ es..rm d

~ad.':'!!!....r..~i.!£!!! .. }? 'L ~t ':' !! !!! !f .o f J ! ! . E E . . . . 9 ! _ g~"!'!a~.Ea!1J{14in the tales. The conclusions do not contain material useful

for preaching such as we find in paradigms. Clear~y the tales

do not playa part in the sermon ~ d~ the paradIgms. They

exist for the pleasure of the narr~elf.

-Tales or~~ted!.~accordi?g to D~belius, ~n three .ways: by

.....Ef..IJding p~ra:I..ig!,~. by" mb:o~UClI~.~.J~elgp .J!',!h~,_.or ..!!y

borrowi!J.gJo!.~~~~Lfhe process of extending para-

. igms was somewhat automatic when the paradigms were set

free from their context in a sermon. The storytellers and teach-ers, "men who were accustomed to narrate according to the

plan of the usual miracle-stories or in the style of. current

anecdotes.T" introduced a richer miracle content mto the

paradig~ and they employed all the usual ?arrat.ive elem~nts

to make the tales lively. Also, brief paradlgmahc narratives

were extended by employing motifs perhaps strange to the

original paradigm. For example, Dibelius feels that the story

of Jesus walking on the water (Mark 6:45-52 and pa.rallel

passage, Matt. 14:22-33) may hav~ resul.ted from th.e. intro-

duction of an epiphany motif (mamfesta:lOn of ~e divine on

earth) into a primitive narrative of Jesus mten:enmg helpful.ly

in a difficulty caused by winds and waves. At times non-Chris-

tian stories were simply taken over as wholes.

f t h healin of the woman with the issue and the.!he account 0 e. gouse of Jai rus i s an exception. liThe at·

lalSIJ:lg from the dead In the1d

I t ly destroy the structure of thetempt to separate them wou com p e e. ., lb·d 72main, together with the subsidiary narrative. I., p. .

ulbid., p. 76.ulbid., p. 79.ulbid., p. 99.

"-I -

/"

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 17/48

I

==

==

THE DISCIPUNE APPLIED BY DIBELIUS AND BULTMANN

~gends. Legends, "religious narratives of a saintly man inwhose works and fate intereSt is taken ';'-a;:;'-;;e-iil-ih,;cnurcrr

to satisfy .. double-d';-;ir;:}he'deSire t;-=~ow something of the

~.E:'an vlftueunc!.J"t of the hol)L.Illi:JLJlna-wo'"ii'Wnill )lj

/ ,.l~ry_oiJesu~and th~ desire which gradually developed to

~know ~.!!LlnJl1'i~11mJhis_way. The story of Jesus when he

IStwe ve years old (Luke 2:41-49) is the story of Jesus whichshow~ most clearly the qualities of legend.

Itl~ natural to think of legend as entirely unhistorical, and

Dibellus a?knowledges that the religious interests of the nar-

rator may lead to an unhistorical accentuation of the miracu-

lous~l~oa glorifyi~g of the hero and to a transfiguration of his

li~e. . Yet, Dibeltus stresses that it would be wrong to dcny

~Istoncal content to every legend in the Synoptic Gospels.

A narrator of legends is certainly not interested in historical

confirmah.on, nor does he offer any opposition to increasing

~,e material by analogies. But how much historical tradition he

ania:,~n illa legend depends on the charactcr of his tradition

Ony.

i Myth. D~belius is convinced that the story of Jesus is not

o mythologICal origin; the £..aradigms, the oldest witness of

teprocess of formation of the tradition, do not tell of a mytho-

;gl~a~.~ero: __ A Christ mythology, evident in the letters of

a~:b ;. ans~ late ,in.the process of the tr'l,dition's formation.

. 1 e , 1~SJ U ges that only to the small~tent is the Svnop'.tic tradItIOn of a mvtholo«t I h 'who h d lb =-,gJ~,!c_amcter. The only narratives

lC escn e a mytholog' I "ti b t ica event, a many·sided interac-

On e ween mythological but not human persons"" are the

records of the ba tismal miracle, (Mark 1:9-11 and arallel

PIalssages),~mptation of [esus (Mark 1'12-13 andPparale passages I, ana fh-- -",,--.-.:.:: . • passages). ~ e t.!;,!s.!!J~1!lation(Mark 9:2-8 and parallel

Saying.. Although D'b I'terra1orthe"'S t' GI e IUSemphasizes the narrative rna.

ynop IC ospeIs, he does deal with ~SJ\Y!!1gs_

"Ibrd.• p. 104,"Ibrd., p. 108."I bid., p. 109"Ibid., p, 271:

LITERARY FORMS AND THEm SITZ 1M LEBEN

. . . . Q ! J esus. He finds preaching, especially catechetical instruc-

tion, as the place of formulation of such teachings, but he pre-

supposes a law different from the law concerning narrative

material to be at work in the sayings of Jesus. Just as the Jews

of Jesus' day took the rules of life and worship more seriously

than they took historical and theological tradition, so the Chrts-j; <>(

tians treated the sayings of Jesus more senously than the nar- ~ratives. The sayings of Jesus were important, for they dealt

with Christian life and worship, and, when the early Christian

teachers transmitted the early exhortation, the words of Jesus

were naturally included. Dibelius reminds us in this connec-

tion that "all the sayings of Christian exhortation were regarded

as inspired by the Spirit or by the Lord. Thus all of them ap-

peared as exhortations 'in the Lord', if not as exhortations of

the Lord."2.

As the sayings of Jesus were transmitted, however, some

modification took place. The tradition emphasized and

strengthened the hortatory character of the words of Jesus and

thereby altered the meaning and emphasis of words whichwere not originally hortatory. There was also a tendency to

include ehrtstological sayings so as "to obtain from the ,words

of Jesus not only solutions of problems o.r rulesJor ones own

life but also to derive from them some Indications about the, d 1 "21

nature of the Person who had uttere t rem,

TheFormsof~

Bultmann does a detailed analysis of all the Syooptic ma-

terial within the two generalAjvj.<;iOj1.§of the discourses of

Jesus and the narrative material. !he discoursesof JeSIlf~7are

divided into two main groups:. apophthegms and ~~l:~

sayings; but Bultrnann also gives a separate treatment of J . ji'Xl~gs" and parables although by content they belong ~o.the

dominical sayings ..1!'.~2!,!!,!ati~~?,aterials. are. also dlVl?:d into two major groups: mirllcJe stones and hlstoncal llaf rativ s

and.Iegends~

Apophthegms. Bultmann's category "afophtheg.ms" Is basi·

cally the same as Dibelius's "paradigms. Itapplies to short

"Ibid., p. 241."Ibid., p. 246,

/

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 18/48

J

THE DISCIPLINE APPUED BY DlliELIUS AND BULTMANN

sayings of Jesus set in a brief context. But Bultmann doe§ not

agree that the form arose in preaching in eve!y"sase. Because

'Oltll~he-uses the" term"apophlhegm" instead of "paradigm"

for it is a category from Greek literature denoting merely a

short, pithy, and instructive saying which does not prejudge

the matter of origin. Bultmann sees three different types of

apophthegms characterized by the different settings or causesfor the sayings. C~tr~rsy dialogues are occasioned by con-

flict over such matters as Jesus' healings or the conduct of

Jesus and the disciples; scholastic dialogues arise through

questions asked by opponents; biographical apophthegms arein the form of historical reports, --- -,-

The Sabbath healing of the man with the withered hand in

Mark 3: 1-6 is an example of a controversy dialogue. Bultmann

sees the controversy dialogues as literary devices arising in

the discussions which the church had with its opponents and within itself on questions of law.

The question concerning the chief commandment in Mark

12:28-34 is a schplastic dialogue, There is a close relationship between the scholastic dialogue and the controversy dialogue,

The essential difference between them, as the title indicates, is

that in the scholastic dialogue a oontroversy is not the starting

point, but for the most part the starting point is a question

asked the Master by someone seeking knowledge.

The account in Luke 9:57-{l2 is ~ ~iQgr. 'H'.hica lapophtM gm-'-.

Biographical apophthegms are so named because the apoph-

thegm purports to contain information about Jesus. The spe-

effic starting point of the biographical apophthegm, although

not of the controversy and scholastic dialogue, is the sermon.

"The biographical apophthegms are best thought of as edify-

ing paradigms for sermons. They help to present the Master as a liVing oontemporary, and to comfort and admonish theChurch in her hope.""

In Bultmann's opinion all three types of apophthegms are

./ ~41ear-constru~Q!lUlf_th<r-churclt.-They are not historical

reports. Itis true that Jesus engaged indisputations and was

asked questions about the way to life, the greatest command.

ment, and other matters. Itis also true that the apophthegms

could easily oontain a histOrical reminiscence and that the

-Bultmann, HIstOfV o f th e s~1IOpI/c T,aditkm, p. 61.

28

LITERARY FORMS AND THEIR srrz 1M LEBEN

f dialogue may go back to Jesus himself. <,decisive saying 0 a 1 th t d are church constructions-But the apophthegms as e~ S an a be seen by eompari-

Palestinian church co~structlOns as; ~e most of the apoph-

son with similar rabbinic stor~esilie ~;e of the church.

thegms were develop~~ e~i6e~us that the apophthegm beganBultmann agrees WI . th h an interest in history

to develop novel"li~e tend:n~~e~e r:u!phthegm is affected by

or in storytellmg. As soo I d f telling we meet with

an interest. in history or d'~2~e~: ~u~7tioners in the apoph-more preCIse statements. d ill lly They are char.

thegm, for example, are describe sP:~hac;s e~en as disciples,

acterized as opponent~ ~f l~su:.n~r ;effied individuals for thew he re as th ey we re on gm a y p

most part,

, h in s of Jesus are divided by Dominical Sall'n~. T e §flYl g ch' fly according to their

h in groups reBultmann into tree mOl

f I d'ff rences are also involved.

actual content, although anna b 1 :ophetic and apocalypticThe three groups are: prover. s, p uI ti s

d mumty reg a Ion .sayings, and laws an com as the teacl}!!!....Qf_"lisllQlllcom-

The "'rocerb shqws~~'~-'--'~-"-';--II J ud ai sm a nd -- t::-_~--"h-- £ wisdom m srae J '

parable with teac ers 0 basi "constitutive" forms areth 0' t Three asic th

throughout e nen. diti ed by the sayings em-f h rbs forms eon 1Ion I

u se d o r t e p ro ve ' . , a ll r ov er bi al l it er at ur e, n ot o n yselves. These forms .exlSt,10 t 0 tic Gospels. The proverb

in the proverbial saY10gsm :h~h yo !rinciIlle o,_.a...de/;];u:'ltjgn

in a declarative f O , 1 J ! l sets _."I ,. a 1'''-- Ex';'ples from the

co;C;;::em;;:;-g";n;;te;.JaUhings. 9r~ers~f:..cL b ndance of the,- . -"" . I d ' "For out 0 tne au,

Synoptic tradition me u "e. 12,34)' "Let the days own

heart the mouth speaks (~;~t." (~1att: 6:34); "The laborer

trouble be sufficient for th 7Y)' d "Many are called, buthi " (Luke 10: ,an 1 d'

deserves 15 wa!fes 22, 14) Exhortations a re pace mfew are chosen (M~tt. .., , hei'L ourself' (Luke 4:23);animp'era@ejorm' l'hysJJ<~aQ,, 'd Y -

d " (Matt. 8:22). Prov-

7're;~e ilie dead to bury thelr own (i~~'"And which of you

erbs also exist In_tI}p t2J;l9~0f,.-4~~Stohi~ span of lifer' (Matt. by being anxious can add one cu ~ t while the bridegroom is6:27); "Can the wedding guests as

with them?" (Mark 2:19).

-IInd., p. trT.

'" " '- .

8/22/2019 What is Form Criticism, Edgar McKnight

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/what-is-form-criticism-edgar-mcknight 19/48

THE DISCIPLINE APPLIED BY DIBELIUS AND BULTMANN

Bultmann shows that there were developments in the prov-

e~bs even after they were written down, and that it is impos-

sible to evade the question whether all proverbs go back to

~he earthly Jesus. The question is especially difficult when it

IS. observed that Synoptic proverbs have parallels in '[ewish

WIsdom hterature. (Compare Luke 14:7-12 with Proverbs 25:

6--7, for example.) In regard to the genuinencss of the prov-er~s, Bultmann sees several possibilities: that Jesus himself

~med some of the proverbs which the Synoptics attribute to

h~m,.that Jesus occasionally made use of pnpular proverbs of

~s tIme: and that the primitive church placed in Jesus' mouth

any Wisdom saymgs that were rcally derived from the store-

house. of Jewish proverbial lore. Bultmann's judgment is that

the Wisdomsayings are "least guaranteed to be authentic words

o.f J:sus; and they are likewise the least characteristic and significant for historical interpretation.""

.Pr Q p,IW tiI! -,!- ,!da pJJ 9!, lyp tic say ing s are those sayings in which

Jesus proclU1med~thearrival of tile Heizn of God and preached the call to repentan~e ., ~l ~....-.,.-. ',"'; , promIsmg sa yahoo lor tnose who were

pr:pared and threatening woes upon the unrepentant."" To

this c~tegory belong sayings like: "The time is fulfilled, and

the kmgdom of Cod is at band; repent and believe in the

gospel" I(Mark 1:15); "Blessed are the ~yes which see what

you see, For 1tell you that many prophets and kinds desired to see what you see d did 'h ' ' an 1 not see It, and to hear what you

ear, and did not hear it" (Luke 10'23--34) "Bl d f' '; esse are you~oor, or yours IS the kingdom of Cod. Blessed are you that

unger now, for you shall be satisfied. Blessed are ou that

weep now, for you shall laugh" (Luke 6:20-21) are Jearl inthis category of sayings. y

thBtuJltm~nhnsees proof in the little apocalypse of Mark 13:5-27a ewis matenal has b ib d d

h k een ascn e to Jesus by the church

an e as s to what ext t th f h '. 'I I . d en e rest 0 t e material must be

SImi ar y J U ged In s . h10 ical " ,orne saymgs t e immediacy of eschato-

Je~us h:~~~~ousness ISso different from jewish tradition thatmust have been the origin. (Luke 10:23-24;

~Rudolf Bultmann "The Stud f hcism , ed. and trans: Frederick b 0Ct e Syn(optic Cospels.~ Form CrfU·

p. 55. . rant New York, Harper 1962)-Ibid., p,56. ' ,

=

28

LITERARY FORMS AND THEIR SlTZ 1M LEBEN

Matt. 11:5-6; Luke 11:31--32; and Luke 12:54-56.) But there

are other passages which contain nothing specifically charac-

teristic of Jesus and where it is most likely that there was a

Jewish origin (Matt. 24:37-41, 43-44, 45-51; Matt. 24:10-12;

Luke 6:24--36; Luke 6:20-21.) Not all sayings which are

judged unlikely to have originated in Judaism come from