Floaters Round Pondsofo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/naturalist-winter... · the South Fork...

Transcript of Floaters Round Pondsofo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/naturalist-winter... · the South Fork...

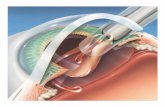

with the microscopic aquatic life, mostlyphytoplankton, which serves as its food. When itis time to reproduce, the male mussels releasesperm into the water column and the females usetheir siphons to draw the sperm in. Fertilizationtakes place internally, and the fertilized eggs areincubated in a tubed section of the mussels’ gillknown as a marsupial gill.

After growing into a larval stage calledglochidia, which takes several weeks to severalmonths, they are ready to leave the female mussel.At this time, the mussel extends a part of itsmantle flap outside the shell that resembles aworm, a small fish, or a tiny crayfish that will serveas bait to draw what will become a host fish to thegravid mussel. Imbedded in the modified flap is aconglutinate packet filled with glochidia, whichbursts when a fish bites the bait and releases thelarvae onto the fish. The larvae attach to the gills,fins, or scales of the fish and become encystedwhere they live as a parasite on the fish for two tothree weeks until they metamorphose intominiature mussels and drop off into the mudbelow.

It will take two to four years for the musselsto become sexually mature. This method ofreproduction insures good dispersal of the youngmussels throughout the body of water.

Some freshwater mussels are very hostspecific and can only use one species of fish for ahost. The Eastern Floater, however, is one thatuses a variety of fish. These include Bluegills,Pumpkinseeds, Yellow Perch, Three SpinedSticklebacks, and Common Carp, all species thatcan be found in the ponds of the Long PondGreenbelt. If for some reason the host fishdisappear from a body of water, it follows that themussel will disappear too.

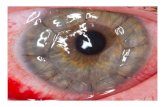

As I mentioned before, the Eastern Floateris a beautiful mussel possessing a shiny greenishexterior with brown and tan concentric bands andlight and dark bands radiating out across the shell

ecolinksFloaters atRound Pondby Jim Ash

If you visit Round Pond in the Long PondGreenbelt during a year when the water level is ata low stage you may find the shells of one of LongIsland’s more interesting bivalves. This freshwatercoastal plain pond, like the others in the greenbelt,is located south of Sag Harbor.

These ponds vary dramatically from year toyear depending on how much snow melt and rainwe get in a particular year. In wet years, the waterlevel can be so high that the water is right up intothe tree line, but in dry years, there is usually amargin wide enough to walk entirely around someof the ponds. It is during those dry years that theponds are most interesting, exhibiting a widevariety of plants that may have lain dormantunderwater for years waiting for the shoreline tore-emerge so they can bloom and set seed again.

It is also in these low water periods whenyou can find the bivalve known as the EasternFloater also called the Fragile Freshwater Mussel(Pyganodon cataracta).

T h e s es e l d o m - s e e nmussels have afascinating lifecycle and areoften thought ofas indicators ofthe quality ofwater in ponds,lakes, and rivers.North America ishome to almost

three hundred species of freshwater mussels andmany—if not most—are becoming uncommonand even endangered because of widespreadpollution and poor water quality in our country.

A beautiful mussel, the Eastern Floaterspends most of its life buried in mud underwaterwith enough of its shell exposed to extend itssiphons out, enabling it to draw in water filled

26 Y

EARS O

F NATURE EDUCATIO

NA quarterly publication of the South Fork Natural History Museum (SoFo) • Winter 2016

Each quarter SoFo features eco-links, written by a member or friend of the Museum. If you wish to submit an article please contact us.

continued on next page

Round Pond Photo: Friends of the Long Pond Greenbelt

Fragile Freshwater Mussel(Pyganodon cataracta)

Photo: Jim Ash

Freshwater Mussel Life CycleIllustration: Freshwater Mussels of Iowa

from the hinge. The inside is lined with nacre, ormother of pearl. In the early twentieth century,many freshwater mussels were harvestedextensively for the nacre, which was used to makebuttons. But it is unlikely that the Eastern Floaterwas used for this purpose because the shell is sothin—which inspired its other common name,Fragile Freshwater Mussel. It is a large musselreaching a length of seven to ten inches. Unlikesaltwater mussels, it is not a sedentary species anddoes not attach itself to hard objects or substrateusing Bissell threads. It moves freely around thepond using its large muscular foot which leaves atrail in the mud showing where it has wandered.

Almost invariably, the first time someonesees a freshwater mussel they say, “Are thesethings edible?” The short answer is yes; however,never having eaten one myself, I can only rely onwhat I have heard and read. The description isthat they have the texture and taste of an old pieceof shoe leather, so forget about freshwater musselsin white wine with garlic, lemon, and parsley. Onthe other hand examination of Native Americanmiddens shows that they harvested themextensively. Whether they were eating them orjust using the mother of pearl for decoration andjewelry is the question.

Unfortunately, 70 to 75 percent of thefreshwater mussels in North America areconsidered threatened or endangered, with a fewspecies possibly having become extinct, makingthem the most vulnerable and threatened groupof animals in the country. Because of the almost-never-ending effort by Congress to weaken and,in some cases, eliminate environmental laws likethe Clean Water Act, this circumstance can onlyget worse. Whether freshwater mussels have themuscles to survive this onslaught remains to beseen.Jim Ash is Vice President of the Board of Directors ofthe South Fork Natural History Museum (SoFo). Heis one of the seven founders of SoFo and served as themuseum’s first Executive Director.

ecolinks theNature

clubhouse

continued from page one

theNature

clubhouse

My Life as a Birder … so far

by Wyatt “Hawking” Case, Birder and SoFo MemberAt SoFo we are delightedto learn about youngpeople who take apassionate interest in thenatural world. Wyatt isone of these youngpeople. He has beenbirding since he was 8 andpossesses a prodigiousvisual and verbalornithological vocabulary.

Wyatt splits his time between Aspen, Colorado,and East Hampton on the East End of Long

Island, where he spends his summers. We wantedto learn more from Wyatt about his interest inbirding, so we asked him some questions aboutbirds and birding when he visited the museum inJune of last year.SoFo: So, Wyatt, as with most birders, a particularbird first caught your interest. Birders call that a “hookbird”, because getting to know or see that bird getsthem “hooked” on birding. What was your “hook bird”?Wyatt: My hook bird was a House Finch. Whathappened was my dog got hold of a House Finchand started to treat it roughly—actually tried to eatit—and I saved it’s life. So I sort of felt connectedto it. We took it to a wildlife rehabilitator and itspent the night there and then it was OK the nextday and they released it.SoFo: That’s very interesting; you really connectedwith that bird. So after that experience with the HouseFinch, did you discover other kinds of birds? What areyour favorite birds?Wyatt: My favorite birds are a Red-tailed Hawk,Barred Owl, Barn Owl, Elf Owl, Canada Goose,and King Eider. My most favorite is the Red-tailed Hawk. When I started birding, I was alwaysinterested in raptors, and the hawk has alwaysbeen a spiritual symbol. Since civilization started,people were always worshiping the hawk; I’m notsure why—maybe because it has power over otheranimals.

SoFo: You’re also interested in other birds besidesraptors, like the Canada Goose, is that right?Wyatt: Yes, I did a presentation at school when Iwas in third grade about the Canada Goose. Italked about their diet, scientific classification,habitat, things like that. We had to researchsomething, and I picked the Canada Goose, and Ipresented it to the other kids in the advancedprogram at my school. SoFo: How is birding in Aspen different from birdinghere?Wyatt: Here, everything is like forest and thebeach, so you can just walk around and see birds

Wyatt “Hawking” Case

Wyatt’s drawing of an Elf Owl drawn from memoryduring the interview.

SoFonews

We are pleased to introduce you to SoFo’s two new Nature EducatorsEleni Nikolopoulos and Xylia Serafy

Both are native East Enders

Growing up in Montaukby Eleni NikolopoulosAs anyone who has ever been to Montauk knows,it is a beautiful place filled with natural beauty.Growing up in Montauk, I’ve had a lot ofexperience with the outdoors. When I wasyounger, I didn’t realize that kids living in the citydidn’t have the same amazing opportunities toexplore the natural world. I didn’t realize howlucky I was to live in a place where I have a beachminutes from my home, an abundance of trees toclimb, forests to explore, and different plants andanimals to observe. My parents moved to Montauk in the 1980s—mymom grew up in Queens and my dad grew up in atiny village in Greece. After moving to Montauk, they bought a smalldiner and worked constantly. We lived in town, inan apartment just on the edge of Fort Pond. Therewere shadbush trees that grew on the edge of thepond that I loved climbing. I used to take anotebook with me and write down all the thingsthat I saw and what I was thinking, but it was

Growing up in Sag Harborby Xylia SerafyI can’t fathom how different I would be if I didn’tgrow up in one of the most beautiful places in theworld, specifically Sag Harbor. Of course in thesummertime, the towns come alive on the SouthFork with all of the summer visitors and beautifulbeach weather, but the time I connected most withnature was when the cold started to bite duringthe autumn and winter time. During this time, the“Hamptons’ mindset” dissipated with all of thestores and restaurants closing for the season, and Iwas left with nothing to do but explore theoutdoors. My parents are both naturalists, and during thewinter, we would tackle the bitter cold at the oceanbeach for walks and exploration. To this day, I keep these experiences alive. I visitedthe ocean every time I returned from college on aholiday vacation, sitting on top of the cold snowwith my layers of warm clothing, photographinghow the sun’s light bounced off the ice, collectingsand dollars that had been dredged inland. It

theNature

clubhouse

constantly when you look up. In Aspen, I like tobird on a mountain, right above my street, andthen you can see all the birds from miles around,you can see more there. In Aspen, we have a feeder,which we don’t have here, and we get a lot ofHouse Finches, Black-capped Chickadees, andsome—but not many—Mountain Chickadees. Weoccasionally get Cassins Finch. We have to godown the valley, to Glenwood, to see the rosy-finch; they get tanagers and migratory birds there,too.

SoFo: Bird migration is fascinating; what makes itspecial to you? Do you know why birds migrate?Wyatt: I don’t usually see the migration, but in thefall it’s great to see the Sandhill Cranes migratingin a giant flock; it’s kind of cool that they can rideon currents and on drafts, like Red-tailed Hawksand other raptors. Birds migrate for a variety ofreasons—to adjust to temperature, or they mightneed new food resources, or there might be toomany of a certain kind of predator that they needto avoid.SoFo: What birding field guides do you like, and whydo you like them?Wyatt: I like Sibley’s when I’m trying to learnabout a bird and I like the Audubon picture guideswhen I’m trying to identify a bird, because you cansee what the bird actually looks like. Sometimes Iuse Petersen’s Guide.SoFo: So, if you saw a new bird that you thoughtmight be a finch or a sparrow, how would you go aboutidentifying it?Wyatt: Well, I would look at the eye; finchesusually have a small circular eye, while sparroweyes are usually oval and tend to be morenoticeable and pop out more. And then I’d look atthe beak; sparrow’s beaks are curved at the top andtheir heads usually have a different pattern thantheir stomachs.We thanked Wyatt for talking with us, and we lookforward to his sharing many more of his birdingexperiences with us during the years to come.

Wyatt’s drawing of a Black-capped Chickadee drawnfrom memory during the interview.

26 Y

EARS O

F NATURE EDUCATIO

N

South ForkNatural HistoryMuseum (SoFo)

P.O. Box 455, Bridgehampton, NY 11932-0455(631) 537-9735 email: [email protected]

The SoFo Naturalist is published quarterly as a benefit of membership

Address Service Requested

Dated MaterialPrinted on Recycled Paper with Soy Ink

BULK RATENon-Profit

U.S. Postage PaidPermit #5

Bridgehampton,NY 11932

wasn’t until I left Sag Harbor to move ontoward my college degree at Ursinus Collegethat I realized how much I missed the variety of different habitats. In Collegeville,Pennsylvania, there are really only forests oragricultural land. I spent my four years workingtowards a Bachelor of Arts in bothEnvironmental Studies and Spanish,graduating with Departmental Honors inEnvironmental Studies due to my honorsthesis, “Conservation of the Antillean Manateein México.” My experiences at Ursinus Collegechanged my life for the better. That being said,I always knew that the nature there wasn’tenough for me. I craved the coastline and thesalt spray in the ocean breeze.

Returning home, and to SoFo again after havinga summer internship with them two years prior,was the best thing that could happen to me outof college. As a Nature Educator, I am learningso much about the relationships betweenhumans and the world around us. I plan tocontinue on to Graduate School in a few years,focusing on Wildlife Conservation in areaswhere there are conflicts with human culture.Finding the balance between indigenous cultureand conservation for the future is where mydreams will take me. I genuinely don’t think Iwould be following this dream if I didn’t growup out here on the East End of Long Island.With the hustle and bustle of summertime, it’seasy to forget nature is the reason this area issuch a desirable place to live.

more creative observation than scientific. As anonly child whose parents worked constantly, Ihad to entertain myself a lot.

When I was a teenager, my parents bought ahouse. Because Montauk is tiny, the new housewas actually less than a mile away from our oldapartment, but it felt like a world away. I hated itat first, but over time I grew to love it, especiallythe forest. Walking in the forest gave me solace.It was the place where I found the most peace,the most spirituality, and where I felt the mostcomfortable in my own skin. The forest hastaught me a lot throughtout my life, but I thinkthat the best lesson is that you don’t need to knoweverything or explain everything. Sometimesnature is unexplainable, sometimes the best thingis just being in the moment observing.When I was younger my father and I used towatch the nature programs on TV and he wouldalways tell me that I needed to get an educationand do something that I enjoy, something thathe didn’t have the opportunity to do. As I grewup, I realized that I wanted to work in a fieldwhere I could help to conserve the natural world,the places that I love so much. I graduated from Stony Brook University with a B.A in environmental studies and recently graduated from Macquarie University inSydney Australia, with a M.S. in Environmental Science/BiodiversityConservation. Now that I have come home, Icouldn’t be happier to be working at SoFo,sharing my love of the natural world with others.

Me and my dad (Stavros Nikolopoulos)

Me and my dad (Dr. Keith Serafy) and a DogfishShark onboard the Southampton L.I.U. Research Vessel