Analisis Pengaruh Economic Value Added, Market Value Added ...

Electronics: A case study of economic value added in ...

Transcript of Electronics: A case study of economic value added in ...

E

Ma

b

c

a

KTPEC

1

cpAr(ulOmo

L

ieSa

1h

Management Accounting Research 23 (2012) 261– 277

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Management Accounting Research

jo u rn al hom epage : w ww.elsev ier .com/ locate /mar

lectronics: A case study of economic value added in target costing

argaret Woodsa,∗, Lynda Taylorb, Gloria Cheng Ge Fangc

Aston University, Birmingham B4 7ET, United KingdomNottingham University, Nottingham NG8 1BB, United KingdomHenderson Global Investors, Singapore 049909, Singapore

r t i c l e i n f o

eywords:arget costingerformance managementVAase study

a b s t r a c t

Whilst target costing and strategic management accounting (SMA) continue to be of con-siderable interest to academic accountants, both suffer from a relative dearth of empiricallybased research. Simultaneously, the subject of economic value added (EVA) has also beenthe subject of little research at the level of the individual firm.

The aim of this paper is to contribute to both the management accounting and value basedmanagement literatures by analysing how one major European based MNC introduced EVAinto its target costing system. The case raises important questions about both the feasi-

bility of cascading EVA down to product level and the compatibility of customer facingversus shareholder focused systems of performance management. We provide preliminaryevidence that target costing can be used to align both of these perspectives, and when com-bined with other SMA techniques it can serve as “the bridge connecting strategy formulationwith strategy execution and profit generation” (Ansari et al., 2007, p. 512).

. Introduction

Strategic management accounting (SMA) has receivedonsiderable attention in recent years (see for exam-le, Langfield-Smith, 2008; Cadez and Guilding, 2008;nderson, 2007; Gosselin, 2007; Shank, 2007), yet thereemains a relative dearth of empirically based researchCadez and Guilding, 2008) and limited evidence on these of SMA techniques (Langfield-Smith, 2008), particu-

arly target costing (Ansari et al., 2007). Simultaneously,

tley (2001) highlights economic value added1 as a perfor-ance measure worthy of further research in the contextf a wider organisational control system, and Gleadle and

∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 1212045282.E-mail addresses: [email protected] (M. Woods),

[email protected] (L. Taylor).1 EVA is used throughout the paper in recognition of the fact that this

s the terminology used within the case study company. It is clear, how-ver, that their model is very different from EVA® as marketed by Sterntewart. Section 2 includes discussion of residual income and alternativepproaches to EVA.

044-5005/$ – see front matter © 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.ttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2012.09.002

© 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Cornelius (2008) note that EVA has been little researchedat the level of the individual firm. These calls for empiricalresearch provide the broad motivation for this paper, whichuses a case study to illustrate how EVA can be integratedinto a target costing system.

The case study analyses how a European multinationalpilots a refinement of its target costing system from oneframed around profit (NOPAT) targets to one based uponproduct level EVA targets within one of its strategic busi-ness units (SBUs). The new target costing system appliessolely to modifications to an existing, highly profitable andstrategically significant product line.

The paper is a direct response to Ansari et al.’s (2007)observation that there is little research addressing thedetermination of the target rate of return in target cost-ing and their question as to whether the use of ROA or avariant of EVA might be a preferable metric to the com-monly used return on sales. Hartman (2000) and Shrieves

and Wachowicz (2001) provide a theoretical justificationfor pushing EVA from corporate down to product level, bydemonstrating that a product’s value added, when basedprimarily on its accounting income rather than cash flows,

ccountin

262 M. Woods et al. / Management Acan be used to measure its NPV. Our case evidence indi-cates, however, that whilst using EVA at product level istheoretically attractive, it remains highly problematic inpractice. Zimmerman (1997) highlights both the financialcosts and the problems of dealing with shared costs andbenefits when using EVA for divisional performance mea-surement, and his criticisms are reiterated by Francis andMinchington (2002) in their study of the introduction ofEVA into a UK water company. Our paper extends theircomments on joint costs and synergies from divisionaldown to product level, and also details the additional com-plexities introduced by calculating multi-period EVA overa product’s life cycle.

We find that where a company reports EVA externallyto the market and also uses it as the primary performancemetric for internal control and decision making, then itis useful in providing a common language to translatecorporate strategy into operational practice. This findingindicates that Otley’s (2001, p. 245) suggestion that “EVA®

pays no explicit attention to strategy” does not always holdtrue.

The case study demonstrates how the introductionof value added measures at product level changes theway that cost reduction strategies are evaluated in tar-get costing by drawing attention to capital costs. Weshow that EVA based target costs encourage more carefulevaluation of make versus buy decisions, and direct man-agement attention to working capital control at productlevel, especially via the introduction of vendor manage-ment systems. This evidence complements Kee and Lane’s(2005) observation that when capital costs are excludedfrom product cost, there is a risk of sub optimal allocation ofcapital.

The study also builds on the broader SMA literatureby exploring the interface between cost management andperformance management. Ansari et al. (2007) noted thattarget costing and performance management systems suchas the balanced scorecard are very similar as they bothstart with the voice of the customer and the shareholderand refine organisational processes to meet the needs ofboth parties. In practice, however, Dodd and Johns (1999)found that the adoption of EVA can cause companies tomove away from customer related performance meas-ures. Our case provides initial evidence of how targetcosting can be used to align customer and shareholderinterests in practice. We conclude that customer valueand shareholder value are not necessarily conflicting andthat Schonberger (1996) is consequently incorrect in hiscontention that management accounting is irrelevant forcontrolling the processes underlying enhanced customervalue.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Sec-tion 2 reviews the interface between target costing andperformance management and presents the theoreticalcase for using economic based profit measures insteadof return on sales in the target costing process. Section3 details the methodology and Section 4 describes the

case study in detail. The concluding discussion addressesthe lessons to be gleaned from the case, and the ongo-ing challenges for management accounting research andpractice.

g Research 23 (2012) 261– 277

2. Target costing and performance management

2.1. Target costing literature

Target costing has been used in Japan since the 1960s,although it was not mentioned in the literature until thelate 1970s (Feil et al., 2004). The literature has since evolvedto include descriptions of target costing principles and pro-cess (Ansari et al., 2005; Cooper and Slagmulder, 1999),descriptions and case studies of target costing use andbest practice within companies (Hiromoto, 1988; Sakurai,1990; Monden and Hamada, 1991; Kato, 1993; Yoshikawaet al., 1995; Cooper and Chew, 1996; Ansari and Bell, 1997;Mouritsen et al., 2001; Swenson et al., 2003; Ellram, 2006;Ibusuki and Kaminski, 2007), and surveys of the tech-nique’s adoption in various countries (Tani et al., 1994;Chenhall and Langfield-Smith, 1998; Dekker and Smidt,2003; Rattray et al., 2007).

The above studies address a range of issues including theuse of market information in price setting, methods usedto identify and meet customer requirements and exam-ples of the initiatives used to reduce costs. There is verylittle discussion in the literature, however, of the way inwhich target costing links into corporate level decisions onperformance management.

In this section we debate these issues by addressingtwo distinct questions. Firstly, which stakeholder interestgroups are served by target costing and to what extent canshareholder and customer interests be seen as complemen-tary? Secondly, what are the pros and cons of alternativeperformance measures for the target rate of return (returnon sales, RI or EVA) that can be used in target costing?

2.2. Stakeholder interests

Ansari et al. (2007) describe target costing as a marketoriented tool used for profit planning and cost manage-ment. Product target cost, calculated as the expected saleprice less target profit, using expected sales price as thestarting point, reflects the market orientation of the costingprocess (Hiromoto, 1988). The target profit for a product istypically based on the strategic plan for the business whichforms the foundation for a corporate profit plan (Kato,1993). The profit plans incorporate a return on capital mea-sure because capital investment is viewed as integral toproduct development.

Target costing therefore appears to explicitly takeaccount of both shareholder (profit) and customer (priceand functionality) needs. This raises questions about howthese potentially conflicting demands can be simulta-neously met, even within a broad based performancemanagement system such as the balanced scorecard (BSC).Bourguignon (2005) notes that Kaplan and Norton’s think-ing about the BSC has shifted from a position whichemphasised customer value (Kaplan and Norton, 1992), toone which proclaims the need to also integrate shareholdervalue management (Kaplan and Norton, 2001). She quotes

Kaplan and Norton as stating that “organisations will getthe greatest benefit” (Kaplan and Norton, 2001, p. 156) fromcombining the BSC with activity based costing and share-holder value management. It could be argued that further

ccountin

btBhtawcmu

ctabItwprh2abcmeap

asitc

2

mutpmmGlsttt

d(rr

pW

M. Woods et al. / Management A

enefit would come from combining target costing withhe BSC. Indeed the overlap between target costing and theSC is recognised by Ansari et al. (2007). This view is not,owever, universally supported. McNair et al. (2001) arguehat target costing does not prioritise customer value at allnd merely exists to control and reduce costs. Similarly,hilst Schonberger (1996) recommends the use of target

osting for product development, he argues that manage-ent accounting is irrelevant for controlling the processes

nderlying enhanced customer value.Bourguignon (2005) critically reviews the potential for

onvergence of customer and shareholder values withinhe BSC. She argues that the BSC assumes that customernd shareholder values are linked by cause and effect2

ut uses the critique of Nørreklit (2000) and the work ofttner and Larcker (1998) and Pascail (2000), to suggesthat this link does not necessarily hold true. For instance,hilst customers may be satisfied, they are not alwaysrofitable (Nørreklit, 2000). Additionally, companies arearely able to prove that better non-financial performanceas any impact on financial results (Ittner and Larcker,001). Based on survey evidence, they found that man-gement relied heavily on preconceptions of what theyelieved was important to stakeholders but did not proveausal links between non-financial and financial perfor-ance. Bourguignon (2005) concludes that there is little

mpirical evidence to prove the view that customer valuend shareholder value are mutually reinforcing and com-lementary performance objectives.

The case study in this paper challenges this perspectivend provides initial evidence that target costing directlyupports the integration of customer and shareholdernterests. A related issue is the question of how to measurehe financial returns from a new product/product modifi-ation.

.3. Target rate of return

A key element in the target costing formula is the profitetric that determines the allowable cost of the prod-

ct. Kato (1993) suggests that in Japanese companies thearget profit is driven by medium term corporate profitlans, which reflect the returns demanded by the financialarkets. Evidence linking product profitability margins toedium/long term corporate profit targets is provided byagne and Discenza (1995) and Kato et al. (1995). Simi-

arly, Cooper and Slagmulder (1997) found that the typicaltarting point for determining the target profit margin ishe historic margin earned by similar products, adjustedo reflect the relative strength of competitive offerings andhe company’s long term profit plan.

The macro level target corporate profit is disaggregatedown to product level to give a target return on sales

ROS) which is an important determinant of the financialeturn generated by investing in a product. The financialeturn may be measured as return on assets, return on

2 Customer satisfaction as a driver of shareholder value has often beenosited within the management literature (e.g. Drucker, 1973; Peters andaterman, 1982; Webster, 1988).

g Research 23 (2012) 261– 277 263

equity, residual income or economic value added. The cap-ital invested, and the associated cost of that capital areaccounted for in different ways by these individual meas-ures. Additionally, the choice of measure can be shown toaffect management behaviour.

The use of accounting measures such as ROS and returnon assets is not ideal because they do not include any chargefor the cost of the capital being used to make a product. Theconcept of residual income (Solomons, 1965) was devel-oped to overcome this problem. In target costing, residualincome (RI) would equal the surplus earned by a productafter deducting all expenses including the cost of equitycapital. This is calculated by reducing operating profits(excluding interest payable) via a capital charge calculatedas (invested capital × WACC). RI is particularly appealingas a performance measure because it is also a valuationtool. The present value of long term cash flows from aninvestment (or product) equals the initial capital invest-ment plus the present value of all future residual incomestreams (O’Hanlon and Peasnell, 1998).

There are two potential challenges to the use of RI as thetarget profit measure in target costing. The first arises fromthe need to identify the capital invested in a product and thecreation of product level balance sheets. This is potentiallyproblematic, particularly where there are multiple prod-ucts and shared production lines. At the same time, whilstit has the advantage of imputing a cost of capital, the RI cal-culation uses traditional accounting profit, which may bedistorted by accounting policies. Partly in response to suchconcerns over accounting distortions, Stern Stewart devel-oped a refined version of RI, marketed under the name ofEVA® (Stewart, 1991).

Stern Stewart argue that RI is a distorted measure offinancial return because it is based on non-cash accrualaccounting figures, and ignores the impact of policieswhich underestimate the “true” capital of a business. Toovercome these problems, EVA® adjusts both the net oper-ating profit and capital figures in published GAAP accounts.The Stern Stewart model requires 164 adjustments to bemade in order to compute EVA®, but they suggest that mostcompanies require only about ten adjustments (Stern et al.,1995). There are wide variations in the precise interpreta-tion of economic value added in practice, with individualfirms making their own decisions about the extent andnature of accounting adjustments.

Whilst EVA may be theoretically superior to either RI orROS, it is seen as difficult to implement in practice (CIMA,2004) and the problems can be expected to be compoundedwhen it is applied at product level. There is a need to main-tain a separate set of GAAP adjusted accounts solely for EVAuse (Zimmerman, 1997; Francis and Minchington, 2002),so for EVA based target costing this includes product levelbalance sheets and income statements. Zimmerman (1997)discusses the problem of capturing the impact of syner-gies in an EVA calculation at divisional level. The design ofsystems to allocate joint costs, shared assets and sharedbenefits down to product level is even more daunting.

There is also a risk of using overly simple or arbitrary allo-cation tools.A further problem arises because different cost of cap-ital may be used to reflect the variations in the risks of

ccounting Research 23 (2012) 261– 277

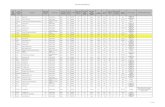

Source: Vinten, 1994.

Compl ete

partic ipation

Particip ation as

observer

Observer as

participant

Compl ete

observer

264 M. Woods et al. / Management A

different divisions/products. In computing divisional EVAfigures, Mills et al. (1996) found that 71% of companiesadopted a simple approach and used a single company widerate. This may seem simplistic, but whilst differential riskweights may be appealing in principle, they are open to therisk of bias and subjective judgement in practice.

The last technical issue raised by the use of EVA appliesonly to large entities where transfer pricing is widelyused, and divisions or strategic business units may nothave full control over the factors driving product prices orcosts. Transfer pricing systems make it difficult to assesseconomic profit at lower level in an organisation, and elimi-nating inter-company transactions at product level is likelyto be resource intensive, tedious and subjective.

The case study which follows looks at both why and howone company addressed the challenge of refining its targetcosting system to one based on EVA. The evidence revealsthat for this company at least, pragmatism serves to tempertheoretical purity.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Explanatory case study

Electronics (real name disguised) is one of the world’slargest electronics and electrical engineering companiesand has an international presence in six core businessareas. Each business has its own CEO and is supported byregional subgroups designed to ensure global market cov-erage. The business CEOs are responsible for performancewithin multiple strategic business units (SBUs) straddlingseveral geographic regions.

The case looks at the processes used and challengesfaced by the multidisciplinary team responsible for theintroduction of product level EVA for one product groupTest. The analysis focuses on the internal structures andproduct costing arrangements within Electronics, and thecase approach used is explanatory (Scapens, 2004). Weuse the data to both examine changing accounting practiceand also link theories relating to value based managementand strategic management accounting. More specifically,we demonstrate the way that SMA techniques such as lifecycle costing, Kaizen costing, attribute (functional) costingand ABC can be combined to form an integrated cost man-agement system (Cooper and Slagmulder, 2004) that alsoserves the interests of shareholders through value basedmanagement.

The research was interventionist in form (Jönsson andLukka, 2005). One of the research team served as a per-manent employee of the SBU, working as a managementaccountant directly involved in the implementation of thenew, EVA product costing system. Action research, in whicha researcher is totally immersed in the organisation, is use-ful for case study work as it provides a richness of insightthat would be difficult to obtain as a complete observer(Whyte, 1991). Additionally, it is well suited to settingswhich link theory and practice (Eden and Huxham, 1996).

The employee researcher, as an active participant in theresearch topic, was able to adopt an emic perspective (Pike,1967) on the accounting changes being introduced. The riskthat an internal perspective might introduce biases into

Fig. 1. Participation and observation continuum.Source: Vinten (1994).

the research was balanced by the remaining research teammembers. These were external to Electronics and played acritical role in defining the theoretical framework for theresearch and also providing a balancing etic perspective(Pike, 1967).

The precise role played by researchers can be rep-resented as a spectrum ranging from the researcher asa complete observer, through to a position of completeparticipation, where the researcher is an employee. Thisspectrum is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Applying Fig. 1, the research was conducted by a teammade up of one complete participant plus two com-plete observers. Most importantly, the research team’scomposition enabled us to move between the logic ofacademia and the logic of accounting practice, enrichingour understanding of strategic management accountingpractice.

Jönsson and Lukka (2005) identify criteria for actionresearch, all of which are fulfilled in this case. The embed-ded researcher was an insider directly involved in theEVA target costing process throughout the period of studyand did not seek to avoid having an impact withinElectronics; participant observation dominated the datacollection process and the study of what participants didand how they behaved under different circumstances;the research was longitudinal and detailed field diarieswere used to log research events over an initial 18 monthtime frame. Further data on the outcomes of the targetcosting process extended the overall research period tofour years.

3.2. Data sources

The study adopted standard methodologies for caseresearch as outlined in Otley and Berry (2004). Researchevidence was collected using multiple sources. Participantobservation in meetings, training sessions, and brain-storming sessions were the primary sources of data,supplemented by internal documentary evidence on thecosting system design, minutes of costing team meetingsplus publicly available evidence from both historic andconcurrent annual reports, broker presentations and webbased information. Semi-structured interviews were con-ducted with nine project staff employed at all levels of theorganisational hierarchy, as well as structured interviewswith relevant departmental managers and shop floor staff.A full list of senior interviewees can be found in AppendixA. The interviewees straddled a wide range of functions

and included the managing director, finance director, stafffrom research and development, and the factory costingmanager.

ccountin

3

abddtaiddp

4

4

ssm

taSrSpshaaelac

rEuogAcKi

tpdatrrcctei

M. Woods et al. / Management A

.3. Data analysis and interpretative validity

The distinct roles played by the embedded employeend other research team members, each with differingackgrounds and levels of practical accounting and aca-emic experience serve to strengthen the validity of theata interpretation. The range of practical experience in theeam ranged from zero to twenty years, and the range ofcademic experience was similar. The resulting differencesn perspectives generated what we would describe as “pro-uctive tension” which took the form of sometimes heatedebates about both theory and practice. These mixed view-oints are directly reflected in this paper.

. Case study

.1. Background

Electronics is a German based multinational with atrong global presence and a long tradition of pursuing atrategy of developing superior products through invest-ent in precision engineering.The case looks at the target costing process used for

he Test product group, which is an upgraded version ofn existing product made by Tweeter, one of the twelveBUs within the highly profitable business area Speaker,enowned for its innovative products. Tweeter, based inouth East Asia, aims to become the number one globalrovider of a product range positioned at the mid end of atandardised market. Test’s mid-market segment is seen asaving huge potential. The aim is to gain 30% of the forecastnnual business, but the market is intensively competitivend dominated by a small number of major global play-rs. Many of Tweeter’s products have long development andong life cycles, combined with rapid initial sales growthnd tough global competition, making cost optimisationritical to business success.

In describing target costing for a product refinementather than a new product, the case demonstrates thatlectronics places a strong, ongoing emphasis on contin-ous product development and highlights the life cyclerientation of the cost management system. Using tar-et costing for continuous improvement is described bynsari and Bell (1997) as akin to Kaizen costing and thease shows that the boundaries between target costing,aizen costing and lifecycle costing are somewhat blurred

n practice.The case study covers four years, which includes both

he pre and post production costing processes for Test’sroduct modification. Long product lives mean that theevelopment time may represent just 10% of the over-ll life cycle. Long term management and redesign effortshroughout the product lifecycle are therefore essential toetaining strong customer orientation and ongoing costeductions after a product’s release. Continuous supplyhain management is also important to the product life

ycle management system, and all businesses within Elec-ronics work with their suppliers in a form of “extendednterprise” aimed at reducing life cycle costs whilst retain-ng customer value.

g Research 23 (2012) 261– 277 265

4.1.1. Historical contextAs a German based multinational, Electronics is exposed

to pressure from both its German cultural heritage andthe broader global economy. Its management accountingpractices can be analysed in the context of the ongoingdebate about the extent to which management account-ing practices have become globalised or remain subjectto national and institutional cultural influences (Jones andLuther, 2006; Becker and Saxl, 2007). This debate is com-plicated by the possibility that even if a specific techniqueis shown to be international in scope, it may still be subjectto local adaptation(s). As Jones and Dugdale (2001) suggest,accounting techniques both shape and are shaped by localcontexts.

In their seminal text on the varieties of capitalism, Halland Soskice (2001) categorise the political economies ofdeveloped nations under the headings of Liberal MarketEconomy (LME) or Co-ordinated Market Economy (CME).Within both types of economy, companies are a centralinfluence on technological change, international compet-itiveness and overall economic performance. Companybehaviour in LMEs is driven largely by competitive marketforces, and the market dominates and co-ordinates eco-nomic relations. In contrast, within CMEs companies makegreater use of networks of relationships outside the formalmarket place as a way of developing expertise and eco-nomic success. Germany, Electronics’ home base, is classedby Hall and Soskice (2001) as a CME.

Companies within CMEs are characterised by theiraccess to what is sometimes termed “patient capital”, asthey are less dependent upon current profits and the AngloAmerican emphasis on shareholder value is less preva-lent. Consequently, one might expect some differences inthe performance measurement and management controlsystems used in CME versus LME based companies. Thedevelopment of a product level EVA within a CME basedcompany, is therefore of particular interest.

The description of Germany as a CME has been chal-lenged by some who consider that there has been a seachange in both corporate governance and managementcontrol structures there in recent years (Jones and Luther,2006). With its economy weakened in the 1990s by unifica-tion, Germany faced increasing international competitionand a period of weak growth. In their interviews with Ger-man managers, Jones and Luther (2006) found a consistentview that the turn of the century marked a pivotal point ofchange in management accounting practice, as traditionaltechniques were discarded in favour of more “modern”ones. A key shift that was observed was a move in favourof Anglo American thinking and greater emphasis on theuse of financial information for decision making. Ahrens(1999) noted that German management accountants (con-trollers) remained distant from decision making but thetwenty first century reality suggested by Jones and Luther(2006), appears different. Our case evidence indicates asimilar shift in thinking within Electronics as evidencedby its adoption (in 1997) of market focused, number

based controls based around shareholder value and EVA.Similarly, the case details the growing involvement of man-agement accountants in the operational activity of thebusiness.

ccountin

of value added.The EVA methodology chosen by Electronics was, and

remains, an individualised variant3 of the EVA® version

266 M. Woods et al. / Management A

4.1.2. Organisational structureFig. 2 contains a summary organisation chart for

Speaker, indicating the areas of responsibility at differentlevels of the business.

Speaker’s CEO is accountable to corporate HQ and heldresponsible for performance within multiple SBUs locatedin several geographic regions. For each business area,Electronics operates regional headquarters in Asia Pacific,Europe and America which provide support and oversightfor the relevant SBUs. Regional headquarters supports thebusinesses through research and development, procure-ment, process design, co-ordination of quality control andproduction, and management of wholesale distribution.Additionally, it provides central HQ with oversight of theSBUs via its management accounting and internal controlfunction and monitoring of local manufacturing.

The SBUs, supported by the regional headquarters, holdresponsibility for all new product introduction, productinnovation/modification and associated research, devel-opment and marketing. The complementary roles of theregional HQ and the SBU mean that performance man-agement and control requires close co-operation betweenthem.

The structural arrangements within Electronics encour-age the lateral flow of information, whilst verticalstructures provide a framework through which theSBUs report to the business CEOs, who in turn reportto the group CEO. The lateral structures focus atten-tion on customer value, but satisfying customers whilstsimultaneously improving manufacturing efficiency andeffectiveness requires close interaction between staff atthe SBU and regional HQ. Product development and inno-vation processes are customer-centric (Galbraith, 2005)and in Electronics they are based around multi-functionalteams. The interlinking of business based vertical reportingstructures and multi-functional lateral teams in Electron-ics mirrors the organisational structures identified in bestpractice companies in the CAM-1 target costing research(Swenson et al., 2003).

4.1.3. A historical perspective on managementaccounting and costing in Electronics

In the early 1990s the company harmonised its financialand cost accounting systems, and introduced target costingacross the group. The motivations for introducing targetcosting are not fully documented but include referencesto rising costs resulting from growing product complexityand the challenges presented by increasing internationalcompetition. Such influences mirror those suggested byboth small sample studies (e.g. Swenson et al., 2003) andsurveys (e.g. Dekker and Smidt, 2003) which identify costreduction as the primary reason for the adoption of targetcosting. Other motives include cost disclosure and under-standing, continuous improvement and competitiveness,improving supplier communications and improving designand accountability (Ellram, 2006). Given the growing needto retain competitiveness and emphasise customer value,

these other motives may also apply within Electronics, evenif they are not formally recorded.

The use of target costing in Electronics from theearly 1990s onwards is confirmed by both internal

g Research 23 (2012) 261– 277

documentation and external evidence (including academicpapers). These show that the group regard it not just as acost control technique but a cross-disciplinary, customerfocused management process. From the very beginning,the design/re-design process, pushes the challenge of themarketplace back through the chain of production to prod-uct designers (Cooper and Chew, 1996). Target costing iswidely used across the whole group to reduce costs overthe entire product life cycle, whilst retaining focus on cus-tomers’ perception of product worth.

In the 1990s, in line with its group wide use of earnings(NOPAT) as the principal performance measure, the targetcosts were set using the formula:

target cost (allowable cost) = expected sales price

− target NOPAT

Target profit figures were cascaded down from thegroup Board of Directors to business areas, SBUs (withoversight from regional headquarters) and ultimatelydecomposed down to product level, by referencing historicmargins and the relative strength of competitor prod-ucts. This approach is in line with that observed by Gagneand Discenza (1995), Kato et al. (1995) and Cooper andSlagmulder (1997).

As competition began to erode profits, the challengefor the group was to find a way of balancing customerrequirements, market allowable prices and required profitmargins over the long term and across a wide array of dif-ferent businesses. In late 1997 Electronics recorded whatwas described as “unsatisfactory earnings quality and anincrease in business assets, primarily in working capital”(Annual report, 1998, p. 49). Cash flows were weak dueto substantial capital spending and a build up of workingcapital. Earnings were weakened by the fact that certainbusinesses (most notably Speaker) were highly profitablebut their profits cross-subsidised loss making areas of thegroup. Electronics acknowledged a group wide need forbetter asset management, and a strategic review of thebusiness portfolio, led to plans to improve long term groupwide financial performance. In late 1998 EVA became thebinding control and performance metric across the entireorganisation. A positive group level EVA by the end of thefiscal year 2001 was formally declared as the target.

Electronics were keen to externally report the group’sfinancial results in terms of both EVA and EBITDA (Earningsbefore Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation)whilst focusing the internal control system on EVA. The aimwas for the internal emphasis on making more efficient useof business assets to be used to leverage higher post taxoperating profits. Combined with capital restructuring anda reduced cost of capital the result would be higher levels

3 As per footnote 1 it is for this reason that the EVA® notation is notused with reference to Electronics. The precise definition and method ofcalculation has changed over time and the accounting adjustments do notexactly match those proposed by Stern Stewart. The in-house handbook

M. Woods et al. / Management Accounting Research 23 (2012) 261– 277 267

Central HQIntroduc�on of new prod ucts

-Marke�ng-Prod uct innova�on p lan ning-Prod uct deve lopment

Business Area 1 (EVA assessed)

Business Area 2:Speaker

(EVA assessed)

SBU 1SBU 2:Tweete r

America AffiliatesRegional sa les

Regio nal HQ-Manu fac turing- Global Procur ement-Process design-Produc�on/quality con trol-Research & dev elopment-Distribu �on to wholesal e-Management Ac coun�ng & Internal Con trol

Countr y A P lantManu fac turing

Asi a Pacifi c Affiliates

Regional Sa les

Countr y B PlantManu fac turing

Europe AffiliatesRegional sa les

SBU 3.. . ...SBU 12

Business Area 3.. .(EVA assessed)

...Business Area 6(EVA assessed)

ganisati

wttiecswtai4da

mirEt

jocbr

Fig. 2. Or

idely popularised by Stern Stewart in the 1990s. Elec-ronics measured EVA as the net operating profit afteraxes (before financing cost) minus an ‘appropriate’ cap-tal charge for the opportunity cost of all business assetsmployed to produce that profit. At group level, the capitalharge reflects the minimum return required to compen-ate equity and debt investors for bearing risk, i.e. theeighted average cost of capital. For operational units,

he capital figures are based on internally adjusted bal-nce sheet valuations and risk adjusted cost of capital ratesntended to reflect the differing business profiles. Section.2 includes discussion of the problems encountered inrafting product balance sheets and determining a riskdjusted cost of capital.

The decision to choose EVA as the core performanceetric can be explained by EVA’s popularity at the time,

ts widespread promotion by consultants, and the concur-

ent product and capital market pressures being faced bylectronics. Gleadle and Cornelius (2008) similarly foundhat market pressures act as powerful catalysts for theustifies the use of a simpler EVA for management accounting purposesn the basis that “we have deliberately limited these (theoretically con-eivable) adjustments to those relating to certain financing transactions,oth to make the calculation of EVA less complex and to ensure as close aelationship to external reporting as possible.”

on chart.

introduction of EVA. Convergence theorists argue that com-petitive pressures were encouraging reform of the Germancorporate governance system in the 1990s, and a switchtowards Anglo-Saxon governance models. The push forchange was particularly strong for Electronics, as its poorearnings record had led to a return on equity of less thanhalf that of its major competitors. With its widely dis-persed share ownership the result was that Electronic’sstock market valuation was subject to a hefty conglom-erate discount. Shifting to EVA was viewed as a usefulway of improving the group’s market value, as its pro-ponents argue that stock market performance is moreclosely related to EVA than accounting measures of income(Stewart, 1991; Tully, 1994). Value growth was partic-ularly important in the light of a planned NYSE listingwhich was central to the group’s financial improvementprogramme.

The company’s top executives expended significanteffort on promoting EVA as the internal financial perfor-mance metric. In the words of Speaker’s Finance Director“it’s actually a natural development to use target EVAinstead of target profit in defining the allowable cost of

a product, so that cost of capital can be considered incost avoidance and cost saving programmes. . .. our hold-ing company is assessed by EVA so we then need concreteaction to deploy it in all group companies.”

ccounting Research 23 (2012) 261– 277

Product Concept

Product

Prospec ts, Pro file

Pass?

Econo mic P roduct Plan

(EPP)

Approv ed?

Target EVA and ta rget

costs & risk mana gement

Phase 1mar ketin g and EPP

refinement

Pilot run

passed?

Released for serial

production

Customer use tes t and sales

test

End o f Su pport

Phas e out C oncept

No

No

Phase 2

Phase 1

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

268 M. Woods et al. / Management A

Seeking to align group and product level performancemetrics suggests that the decision-making and controlsystems in Electronics reflect what Chua (2007, p. 492)describes as “strategy-accounting talk”. That is, one inwhich corporate level strategies – in this case shareholdervalue added – are dispersed to local sites by specifying thefinancial templates that are to be used.

Product level EVA was piloted for the Test product range,selected because it was seen as a key driver for businessvalue creation in the group’s five year strategic plan. TheEVA target for Test products was set higher than the over-all group average, reflecting their strategic importance, andthe annual EVA target increased steadily over the five yearplanning cycle. Central HQ sets the annual EVA targets, andmanagement accounting staff in regional HQ are responsi-ble for monitoring both the actual EVA against budget andthe sensitivity of Test’s EVA to changes in price, volume,development cost and other cost changes. Actual EVA andforecasts for the remaining life cycle are reported annuallyto central HQ.

The remainder of the case describes the incorporationof EVA into the target costing system for Test products.

4.2. The target costing process

4.2.1. OverviewAn effective target costing system must be a highly

disciplined process (Cooper and Slagmulder, 1997). In Elec-tronics target costing aims to shape a product’s value indevelopment and reduce total costs over the life cyclethrough continual redesign. The company subdivided thesystem into two core phases: pre and post production.Phase 1, split into four stages, deals with the achievementof target cost during the product development (or mod-ification) stage, i.e. prior to the start of mass production.Phase 2, termed improvement costing, is similar to Kaizencosting and aimed at cost reductions via redesign after thestart of production. A breakdown of the stages in the prod-uct life cycle cost management process is given in Fig. 3. Theapproach used in Electronics fits with the definition sug-gested by Kato (1993, p. 36) in which there is no distinctionmade between target costing and life-cycle costing.4

The key change resulting from the use of EVA targetsfor Test was the incorporation of the cost of capital intoproduct costs and subsequent analysis of cost reductionopportunities as shown in Fig. 4.

The traditional use of NOPAT as the measure of targetprofit means that the cost of capital, including any capi-talised research and development costs, is ignored in thesetting of the target cost figure. Consequently, traditionaltarget costing focuses on seeking cost reductions throughchanges in the type/source of materials, and managementof labour and factory overheads via product or compo-nent redesign, or the reconfiguration of processes. Fig. 4

highlights the scope for additional cost reductions throughrethinking the capital that is being used in the manufac-ture of a product. For example, simple changes that increase

4 Guilding et al. (2000), Cadez and Guilding (2008), and Langfield-Smith(2008) are amongst those who differentiate between the two techniques.

Fig. 3. Product life cycle cost management process.

the extent of standardisation of either components or pro-cesses may lower capital costs and raise the unit valueadded.

This inclusion of capital costs into the target costingformula effectively increases the target cost above thatidentified in traditional target costing by the amount ofthe unit capital costs. Nonetheless, the expected sales priceremains the same under both approaches.

For Test products, the EVA target cost is based on “retailprice minus”, and setting the expected retail price is the

first stage in the process, as detailed in Section 4.2.3. Thissuggests that there is not necessarily any reason to expecta change in the emphasis or attention being given to cus-tomer value under an EVA based system as opposed to a

M. Woods et al. / Management Accounting Research 23 (2012) 261– 277 269

Capital Co st

Standard iza�on o f partsStandard iza�on o f produc�on equipment

Reduc�on in sto rage req uireme nts

Labour/O verhead Co stsSimpli fica�on of m anufacturing/a ssembly/s erv ici ng pro cesses via cha nges in:

designmaterial func �on

Mater ial Co stsCheap er Mater ials

Elimina�on of "ni ce to hav es"Integra�on of func�onal ity

uction

tmfwti

4

plt

Hae

TT

Fig. 4. Cost red

raditional system. If the expected sales price under bothethods is determined by customer value, the customer

ocus may, in principle, be retained. The key question ishether or not this focus is sacrificed at a later stage in

he costing process, when the search to reduce costs isntensified.

.2.2. The target costing teamSpeaker (the SBU) is accountable for its overall EVA

erformance, but overall responsibility for achieving theifelong EVA targets for Test rests with a cross-functionaleam led by the Managing Director of Speaker.

Team members are drawn from SBU and regional

Q staff and cover a range of functions including salesnd marketing, R&D, procurement, quality control, designngineers, manufacturing, logistic management corporateable 1arget costing team.

Job title/functional area SBU based Regional HQbased

Managing Director and Team leader√

Product Manager√

Research & Development√

Procurement√

Quality Control√

Manufacturing√

Logistics√

Sales & Marketing√

Management Accounting & Finance√

opportunities.

controlling (management accounting) and finance. Table 1shows that the team is not just cross-functional butalso structured to facilitate good vertical communicationbetween R&D and production units within Speaker andthe staff at the regional HQ. Team leaders and memberschanged over time, but a cross-functional target costingteam has now been in place for more than four years.

Team responsibilities include both product earningsmanagement and capital asset management. Changes incapital assets on the product balance sheet directly affectthe capital charge that is included in product cost. Con-sequently, if design modifications require asset purchasesabove a threshold level then the team recalculates theresulting manufacturing costs and their impact on productEVA (see Section 4.2.3.3 for details).

Fig. 5 details the areas of individual responsibility in thetarget costing team.

Fig. 5 shows that management accounting and financestaff take responsibility for cost of capital and indirectoverhead control (mainly corporate selling and administra-tion expense). R&D, engineering, purchasing, logistic andproduction-staff, under the leadership of the product man-ager, hold responsibility for reducing product related costs,some of which are also capital in nature, e.g. the R&D soft-ware development cost.

Performance related pay for senior executives at both

the SBU and regional HQ is tied to the EVA target of therelevant business arm of Electronics. The target costingteam’s performance related pay is based around the man-ufacturing cost savings achieved, not EVA. Management

270 M. Woods et al. / Management Accounting Research 23 (2012) 261– 277

Marke t Price

Target EV A per Unit

Target Ind irect Overhe ad – se lling,

admin ist rat ion e tc

Work ing capi tal control

R & D and tooling costs

Softwa re co sts

Mechanical design

Process d esign e.g. assembly

TARGET UNIT

MANUFACTU RING COST

LIFE CYC LE P RODUCT

MANAG EMENT

Corporate Ma rketing

Senior sta ff member in financ e and

controlli ng

Corporate financ e and cont rolling

Finance Directo r & factory

perfor manc e cont roller

Other tea m members e.g. d esign

engine ers, pro ces s d esigners and

quality cont rol s taf f unde r th e

direction of th e product manag er

WHOLE TEAM

onsibili

Fig. 5. Allocation of resp

accounting and finance staff are assessed by additional keyperformance indicators such as working capital turnover.This arrangement fits with the view from the literaturethat managerial performance should be assessed againstthe areas over which they have direct control.

4.2.3. Phase 1: target costing during productmodification4.2.3.1. Market and functional analysis. Fig. 3 shows thestages of product life cycle cost management within Elec-tronics. The first phase involves a conjoint analysis of theproduct specific market and customer requirements, con-ducted by the sales and marketing team together withdesign engineers. For Test products, the emphasis at thisstage is on the scope to modify existing designs. Thisincludes evaluation of current market conditions, competi-tors’ strategies, projected demand and market share for arange of potential prices over the full product life cycle.

The resulting findings become inputs into the devel-

opment process, aimed at understanding the functionalityand quality requirements of customers and the price theyare willing to pay for these features (Kee and Matherly,2006). The marketing team and design engineers solicitties in the costing team.

input from customers and use value analysis to analysehow much customers are willing to pay for design inno-vation(s) and other product features. Functional analysisand value engineering are used to decompose the productinto engineering sub-functions that are linked to customerrequirements, as illustrated in Table 2. In this way, theengineers’ view of the product is linked directly back tothe customer’s view, which is primarily functional in itsorientation.

Table 2 shows three core customer requirements –sound clarity, ease of use and aesthetic design. Each ofthese requirements and the associated sub-functions areranked to reflect the feedback from potential customersand measure their contribution to the product price. Theanalysis is similar to the “pricing by functions” used insome Japanese companies (Tanouchi, 1991) and its use byElectronics in product modification reflects Ansari et al’sobservation (2007) that value engineering in Japanese com-panies embraces several stages in a product’s life cycle,

namely concept, initial design and design development.Table 2 thus serves to open up the so-called “black box” ofcustomer value determination as described by Ansari et al.(2007).

M. Woods et al. / Management Accounting Research 23 (2012) 261– 277 271

Table 2Linking customer requirements to engineering functions.

Engineering function Ranking Customer requirements

Sound clarity Ease of use Design aesthetics

Overallquality

Frequencyrange

Level ofinterference

Switch Safety Soundadjustment

Size Weight Appearance

Acoustic performanceOutput xx xxRange of power xxx

Mechanical designOn/off switch xxx xx xVolume control xx xxxx xxInput/output points xx x xx

Mechanical designHousing xxx xxxx xxxxxColour xxxx

Software design

lted1dgmsoomps

aJuitErbpbdb

4pTsaTo

a

Compatability xxxxx xxSensitivity xxxNoise reduction xxxx xxx

Table 2 also shows how customer requirements areinked back to specific engineering functions and tied tohe product’s bill of material, so that the cost of bothngineering functions and sub components can be readilyetermined (Yoshikawa et al., 1994; Albright and Davis,998). The number of “x’s” in the function boxes in Table 2enote the engineers’ assessment of the importance of aiven engineering function to a specific customer require-ent. For example, the ease of sound adjustment that is

ought by the customer is largely determined by the designf the volume control switch. Similarly, the attractivenessf the design will be influenced by both the colour andaterial used for housing the product. In contrast, the

ositioning and design of input/output points is of limitedignificance to any of the core functions.

Ansari et al. (2007) suggest that most of the researchnd literature on functional analysis emanates from theapanese auto industry, where engineering expertise issed to translate customer valuations of product features

nto target cost indices.5 The case evidence illustrates thathe practice has spread into the regional subsidiaries of auropean multinational that is in a different business. Theesulting information ensures that the target price is firmlyased on customer evaluation of functions but also incor-orates an estimated manufacturing cost that provides aasis for detailed target cost splitting at a later stage. Thisata forms the basis for a financial product plan as detailedelow.

.2.3.2. The financial product plan. The financial productlan (FPP) is drafted by the product manager in Speaker.he FPP outlines the lifecycle pricing with projected ero-ion percentage, volume forecasts, target profit margin,

nd total capital investment over a five year timeframe.he SBU’s management accounting team prepare Returnn Investment (ROI) figures based on the FPP, along with5 See Albright and Davis (1998) for a detailed illustration of functionalnalysis in target costing at Mercedes Benz.

a multi-period EVA model that is then used for lifecyclemanagement of Test products. This extended timeframeincorporates capital investment considerations and mir-rors the Japanese approach to target costing described byAnsari et al. (1997). Target EVA is set at a fixed percentage ofproduct turnover, rising annually over the 5 year planningcycle.

The average original net asset base that is used for theEVA calculation includes capitalised research and devel-opment costs6 plus intangibles, as well as five yearsof working capital projections, i.e. accounts receivables,inventories and accounts payable using estimates based ontarget working capital ratios. The challenges of establish-ing the value of product level assets and the relevant costof capital are discussed more fully in the next sub-section.

The cost of capital rate used for Test products is theweighted average cost of capital (WACC) of the relevantbusiness arm within Electronics. By implication, the busi-ness specific WACC suggests that the capital charges reflectthe variation in risks across different business segmentswithin Electronics. It is recognised, however, that the riskweightings applied to each business reflect corporate levelperceptions that may be tarnished by subjectivity (Arnold,2002). The forecast EVA in the product plan is then calcu-lated by deducting the capital costs from NOPAT.

Both the ROI and EVA estimates are then subject tosenior management approval at group level, by compar-ing forecasts against targets for the overall business area.The target EVA for the Test product modification requiredproduct cost to be reduced by 46% from the estimates in theproduct plan simulation. The target costing team thereforehad just twelve months before start of production to closethe cost gap and bring EVA to the required level.

4.2.3.3. Closing the cost gap. The elimination of the costgap requires evaluation of the scope for and cost impact

6 For example, the cost of specialist software and estimated patent andtrademark charges.

ccountin

272 M. Woods et al. / Management Aof reducing and substituting components whilst leav-ing product features and benefits in line with customerrequirements. Central to this process is the informationcollected during the market and functional analysis, whichcan be used to confirm customer requirements, conducttarget cost splitting and also construct target cost indices.The engineers can then try to (re)design the product andits components to fulfil the desired quality, cost and func-tionality mix.

Fig. 6 shows the potential savings in unit manufacturingcosts that can be achieved for one of the Test products bychanging the supplier, altering the components or changingthe method of assembly. As already noted, the EVA tar-get costing approach extends the potential range of costreduction opportunities to include capital costs. For anysuggested solutions requiring more capital resource, suchas the option to make rather than buy, the capital cost (sub-ject to an investment threshold) is assessed by finance andthe management accounting and control section evaluatethe expected EVA Impact.

Standardisation of parts used in housing and othercomponents served to generate substantive savings, reduc-ing direct material costs and the tooling budget for Testproducts by around 20%. Tooling is capitalised and depre-ciated in the accounts, and so savings reduced the capitalemployed and raised the product EVA. This example illus-trates how EVA based performance measurement changedbehaviour and motivated product engineers to seek outways of reducing the capital base. Further savings, realis-able at later stages in the product life cycle were achievedby, for example, redesigning the on/off switch to enhancedurability and facilitate easier maintenance.

The team also considered opportunities to reduce coststhrough production process improvement, but were ham-pered by the existing costing system. The team simulatedthe direct costs for the modified product based on existingplatforms, but found that overhead savings from processenhancements, such as assembly rerouting, were ignoredbecause the system allocated fixed overhead to productsusing a standard volume based budget rate. The limitationsof the traditional costing system had long been recognisedwithin Electronics but the depth of the problem, and result-ing need for change, was highlighted by the need to collateproduct level net asset information in order to calculate theEVA for Test.

To resolve these issues, the Managing Director ofTweeter sent a memo to the target costing team firmly stat-ing that “the cost calculation approach has not changedyet.. . ..We need to change.” Consequently, the costing sys-tem for Test was refined in three ways. Firstly, a zerobased budgeting system was introduced, framed aroundthe assumption of starting a new business from scratchto produce Test products. Secondly, this system wassupported through the implementation of activity-basedcosting (ABC). Activities and cost drivers were identifiedfor overhead related processes in quality assurance, logis-tics, warehousing, industrial engineering, and distribution

centres under forecast output and operating conditions.A budget cost per activity was calculated, and overheadcosts allocated to each product in the Test range. Using datawarehousing, the IT department also designed a specific

g Research 23 (2012) 261– 277

programme to run actual unit cost reports for all of theTest products using the activity-based overhead allocationmethod. It took about three months for the whole costingteam (four staff including a costing manager) to work withdifferent departments to gather the necessary informationand modify the costing system.

In their case study of value based management in a UKwater company, Francis and Minchington (2002) found thecompany faced similar problems with existing costing sys-tems. Like Electronics, their case study company chose tointroduce an activity based system and the change wasviewed as fundamental to the success of the EVA initiative.

The last accounting change required identification of therelevant capital at product level. The problem could theo-retically be resolved by using activity based costing andmanagement to trace assets to products, or by tying cap-ital back to products (Hubbell, 1996; Kee, 1999) but thiswas not done in Electronics. Instead, volume based allo-cation was used for space costs, raw material stocks, andaccounts receivable and payable because it was considered“too complicated and not worth the cost” to use ABC. Whenasked how the capital in terms of floor area for Test productswas determined in the production and distribution centres,the centre managers gave different answers. In production,the floor area was calculated by adding the area occupied byspecific machines to the floor area used in assembly, test-ing lines etc., all of which was allocated using a standardannual production volume. The distribution centre simplyused a volume based allocation method to determine thefloor area required. In other words, for the “service” basedaspects of production – assembly, testing and distribution– volume is seen as the sole driver of space usage, whichmay seem simplistic but is a pragmatic answer to the prob-lem of capital allocation. Nonetheless, the accuracy of theresulting asset pool for the product is open to question.

Certain accounting adjustments recommended for thecalculation of EVA also affect the value of the product assetbase. For example, internally generated intangibles such asbrand name are added back to the capital value in the GAAPbalance sheet. Given the size of Electronics, any productlevel allocation of such benefits would be a “guesstimate”at best, and so no such adjustment was made. Similarly,the EVA calculation was further simplified by opting not tocapitalise the operating lease payments on equipment usedfor manufacturing Test products. Nor were one-off researchand development costs for Test capitalised.

Electronic’s approach matches the findings of Francisand Minchington (2002) in demonstrating that companiesfind it difficult and arbitrary to establish a value for capitalat divisional or product levels within the organisation.

The above changes made it possible to reflect certainoverhead savings within Test’s unit costs and more clearlyassess the impact of cost saving efforts on unit product costsand EVA. Savings on materials and components reduced thecost gap by 30% and changes to assembly processes andpartial relocation of some assembly activities resulted inthe target unit manufacturing cost for Test products being

successfully achieved prior to the start of mass productiontwelve months later.The way in which the EVA based target costing systemtriggered the introduction of ABC costing, a form of ZBB

M. Woods et al. / Management Accounting Research 23 (2012) 261– 277 273

er unit s

acSap1

4

ftaa(fiatb

7ctnEt

smimdpt

mtmmTmfwu

Fig. 6. Unit cost saving proposals. *P

nd product level balance sheets and income statements,learly illustrates the complementary nature of many of theMA techniques identified by Cadez and Guilding (2008). Itlso suggests that accounting practice is subservient to cor-orate strategy, rather than independent of it (Hiromoto,988).

.2.4. Phase 2: target costing post productionIn Phase 2, the project team faced the new challenge of

urther cost and EVA improvement. Post production costargets are used throughout Electronics to link the targetnd life cycle costing systems, in a similar way to thepplication of Kaizen costing in Japanese automobile firmsMonden and Hamada, 1991). SBU cost saving targets areormally set in the annual budget, and actual cost sav-ngs for each product family reported on a monthly basisnd compared against budget. Approximately 20–30% ofhe management team and target costing team’s annualonuses are tied to the achievement of these targets.

For Test products the cost reduction target was set at.5%, taking into account the lifespan service and repairosts, salvage costs and phase-out expenses. Achieving thearget was seen as central to the success of the overall busi-ess unit, and also directly impacted upon annual productVA through both cost savings and capital investment addi-ions/reductions.

The challenge for the project team was that limited costaving opportunities remained after mass production com-enced as 75–80% of the cost had already been determined

n Phase 1. Nonetheless, the long life cycle of Test productseant that the company viewed cost and capital control

uring the manufacturing stage as equally important to theursuit of both customer and shareholder value maximisa-ion.

Efforts were concentrated on continuous supply chainanagement, the relocation of service and repair processes

o Indonesia or China and tighter working capital manage-ent. For six months the target costing team held weeklyeetings, chaired by the R&D director, to monitor progress.

he meetings served as both the project management

echanism and also the formal communication channelor cross-functional teamwork. Monthly cost saving reportsere produced, with savings calculated against baselinenit manufacturing cost, i.e. the yearly standard unit cost

aving (Euros) in manufacturing cost.

applying the zero based budgeting approach introducedin Phase 1. The standard cost was revised downwardsannually to reflect the new figure which then became thebaseline cost for the subsequent year. In this way productcosts were managed downward throughout the whole lifecycle.

The involvement of suppliers was central to the achieve-ment of cost savings during this phase of target costing.Test products are “manufactured to stock” in order to meethigh levels of customer demand, and inventory representsa significant portion of the products’ net assets, whilstaccurate forecast sales and MRP planning are critical toensuring optimal stock levels under such a system. Histor-ically, uncertainty in customer forecasts had often resultedin excess stocks of both components and raw materials.

Electronics began working with suppliers to set themannual cost reduction targets. Such co-operation is partic-ularly important in an EVA based target costing system,because vendor management inventory systems can beused to transfer control of stock to the supplier. The resultis lower raw materials stocks and hence a reduced capitalcost of holding the inventory (Fry et al., 2000). As shown inFig. 5, control of capital cost (including working capital) isthe responsibility of the SBU’s Finance Director.

The importance attached to tight inventory controlwithin Electronics and the SBU is illustrated by the fact thatmonthly and yearly inventory turnover targets are assignedto the finance director, the management accountant andthe management team, and 50% of their variable bonusis tied to this inventory KPI. Additionally, Speaker taskedone management accountant with specific responsibilityfor factory level inventory management. Weekly inventorymanagement meetings are held, and chaired by financewith attendance from representatives in purchasing, logis-tics, warehouse and distribution. Most attendees are alsotarget costing team members.

The search for cost savings via relocation of assemblyand production processes for Test products proved moredifficult to achieve because of the technical complexitiesof incorporating the resulting changes in capital into the

product cost and EVA. One option, to sub-contract an oper-ation to a plant in China where labour and factory rentalcosts were lower, was initially rejected because the nec-essary substantive investment in new fixed assets resulted

ccountin

274 M. Woods et al. / Management Ain a reduction in the life cycle EVA for Test. The unit oper-ational cost saving was less than the unit cost of capitalincrease. The target costing team subsequently modifiedthe relocation proposal to shift only the most labour inten-sive portion of the assembly process. This required muchless capital injection, reduced unit manufacturing costsand increased the product level EVA. This illustrates howthe use of EVA based target costing can both extend butalso alter the mix of cost reduction opportunities that aresought. It is interesting to note, however, that investmentdecision making across the overall group is still based uponNPV analysis rather than discounted EVA.

Four years after the start of the target costing pro-gramme for Test products, the unit manufacturing cost hadbeen reduced by almost 50% and working capital improvedfrom 93 days to 60 days. As the products are still in pro-duction, cost savings efforts continue, new targets are setannually and Test products’ actual annual EVA, includingforecast to the end of the lifecycle is reported on a yearlybasis.

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1. Overview

The market and product characteristics of Test closelymirror the intensive competition, extensive supply chainsand long product development cycles that were classed ascharacterising the best practice target costing companiesin the CAM-1 study (Ansari et al., 1997). Furthermore, thesix key principles for target costing identified by Ansariet al. (1997) are systematically applied. Firstly, the cost-ing is price led, with target costs being established ona “retail price minus” basis. Functional analysis is com-bined with value engineering to decompose the productinto engineering sub-functions linked directly to cus-tomer requirements, as illustrated in Table 2. The resultis a target manufacturing cost that satisfies the requiredprofit margin. Secondly, the system is customer focused,with market and functional analysis being used to gainunderstanding of customer requirements and their will-ingness to pay for specific product features. Thirdly, theapproach places a strong focus on design, emphasisingcost avoidance in product and process design across theproduct life cycle. Fourthly, the organisational structurewithin Electronics illustrates cross-functional involvementby combining vertical reporting structures with horizon-tal cross-functional teams, such as the Test target costingteam. Table 1 shows that the team includes membersfrom a wide range of disciplines and their performance isevaluated on the basis of achievement of the target cost.Ansari and Bell’s (1997) principle of supply chain involve-ment is evidenced in Electronics by the close involvementof suppliers in cost saving initiatives, and the use ofvendor management inventory systems. Lastly, a key fea-ture of the target costing system within Electronics is itslife cycle orientation. Operating, maintenance, service and

repair and phase out costs (as shown in Fig. 3) as wellas economic profit are continuously re-estimated overthe full product lifecycle. The early stage redesign of theon/off switch is an example of how engineers incorporate

g Research 23 (2012) 261– 277

future maintenance considerations into early stages of thetarget costing process. Such a multi period perspectiveturns target costing into a three dimensional exercisein which capital cost, maintainability and sales/purchaseprice fluctuations are reviewed and balanced through aproduct’s life cycle.

The target costing system within Electronics thus fits thebroad profile of such systems as described in the existingliterature but is simultaneously highly distinctive in its useof EVA as the measure of financial return. Hartman (2000)and Shrieves and Wachowicz (2001) provide a theoreticaljustification for pushing EVA from corporate down to prod-uct level, by demonstrating that a product’s value added,when based primarily on its accounting income rather thancash flows, can be used to measure its NPV. Our case studyprovides an empirical perspective on the issue, and theimplications for strategic management accounting in fourkey areas. These are: the relationship between accountingpractice and corporate strategy; the impact of an EVA met-ric on cost reduction strategies; the technical problems ofaccounting for capital at product level, and the impact ofintroducing a shareholder value focus into a system whichis commonly seen a customer oriented. We now discusseach of these in turn.

5.2. Accounting practice and corporate strategy

The case study shows that using EVA at product levellinks group strategies with operational activity, reflectingwhat Chua (2007, p. 492) describes as “strategy-accountingtalk”. In the words of the R&D Director, product level EVAfor Test products “links the corporate target of value cre-ation to product management in a consistent manner. It isalso an attempt to get the shop floor to buy into the valuebased management concept as they are already aware ofthe target costing requirement.”

It is evident that accounting staff within Electronicsplay a very important role in connecting product levelperformance management to broader corporate strategy,providing empirical support for Bhimani and Bromwich’s(2010) suggestion of links and interaction between SMA,multi-functional team working and value based manage-ment. Test’s cross-disciplinary target costing team werecollectively responsible for delivering customer value andcontinuous performance improvement within a groupwide performance system that was EVA focused.

The organisational framework of Electronics supportsthis form of accounting involvement at operational level.Whilst the cross-disciplinary team held overall authorityfor product EVA, the functional expertise and oversight wasprovided via vertical structures. In other words, the casesuggests that certain types of organisational structure maybe particularly supportive of target costing.

The broad strategic focus of the accounting systemwithin Electronics also demonstrates the complementarynature of many of the SMA techniques identified by Cadezand Guilding (2008) and the potential oversimplifica-

tion associated with viewing them as independent of oneanother. The boundaries between target costing, Kaizencosting and life cycle costing appear to be very blurred inpractice.

ccountin

5

rTatcaupv2maptTuu

5

fimpcob

tEsfbsWopZfil

rpmtutopiaic

5

r

M. Woods et al. / Management A

.3. The impact of EVA on cost reduction strategies

The use of EVA as the measure of financial returnequires target cost to be redefined to include capital costs.his creates opportunities for savings through cuts in fixednd/or working capital that would not be identified in araditional target costing system. The case evidence indi-ates that EVA based target costing focused managementttention on capital costs. The result was more careful eval-ation of make or buy decisions and the routing of assemblyrocesses, through comparison of the marginal benefitersus marginal costs of the capital used (Kee and Lane,005). Working capital savings, for example via the vendoranagement inventory systems, were easily implemented

nd the inclusion of capital costs into cost saving pro-osals enhanced management control by directly linkinghe capital budgeting and product management systems.his would suggest that traditional target costing perhapsnderestimates the scale of potential cost savings, partic-larly in the area of working capital.

.4. Technical challenges of EVA target costing

The case confirms the extent to which product pro-tability management remains a problematic area foranagement accountants. In the case of Test, efforts to

ush EVA down to product level were hampered by techni-al accounting difficulties which required the constructionf product balance sheets and replacement of the volumeased overhead costing system with one based on ABC.

Kaplan and Cooper (1998) suggest driving EVA downo product level by integrating it with ABC costing, and inlectronics a new ABC system proved fundamental to theuccess of the EVA initiative. ABC was only used, however,or estimating certain product costs and not, as suggestedy Hubbell (1996), to trace assets back to products. The rea-on given was that ABC was too complex and expensive.

ithin a large group such as Electronics, the prevalencef shared assets and transfer pricing added to the com-lexity of the EVA calculation, confirming and extendingimmerman (1997) and Francis and Minchington’s (2002)ndings that synergies make the application of EVA at

ower levels of an organisation highly problematic.Ultimately, the accounting staff within Electronics

esolved the technical challenges of deriving an EVA for Testroducts by massively simplifying the accounting adjust-ents suggested by Stern et al. (1995) down to a level

hat meant the value added measure was closer to resid-al income than EVA. No intangibles were added back tohe product balance sheets and neither research and devel-pment nor operating leases were capitalised. Choosingragmatism over theoretical precision highlights the ongo-

ng divide between theory and practice in managementccounting and the need for further research into improv-ng the techniques currently available for identifying theapital used on a product by product basis.

.5. Shareholder value versus customer value

The use of EVA rather than earnings as the profit met-ic in target costing directly links SMA to shareholder

g Research 23 (2012) 261– 277 275

value based management. At the same time, the case studyaffirms Bourguignon’s (2005) contention that the inter-pretation of the term “value creation” has evolved withinmanagement accounting. Electronics is seeking to mergecustomer value and shareholder value perspectives into asingle performance management system. The shift towardsa shareholder value focus is of particular interest given thecultural context of the case study company and confirmsJones and Luther’s (2006) findings of a change in thinkingamongst German managers in favour of the Anglo Amer-ican approach and increased use of financial informationfor decision making.

The alignment of customer and shareholder interestsin a single target costing system is potentially problem-atic and raises fundamental questions about the extent towhich accounting, as a financially oriented discipline, canserve the needs of a customer focused organisation. TheTest target costing team were required to include mea-sure target cost by including a cost of capital, but the caseevidence suggests that whilst this refinement resulted inchanges to the product costing system – via the intro-duction of ZBB and ABC costing – it did not impact onthe attention given to customer value. In modifying Testproducts the target costing process began by analysing themarket, customer requirements and their willingness topay for new product features. The resulting target price,minus EVA, then generated the target costs, broken downinto functions and components. Post production, the pro-cess retained its focus on customer value, with cost savingsuggestions in both product and process design made sub-ject to customer value analysis. It would appear, therefore,that the exercise was not simply one of cost minimisation,but also of aligning costs with customer value.