DAWES - 1996 - Interagency Information Sharing

-

Upload

ana-julia-possamai -

Category

Documents

-

view

39 -

download

2

Transcript of DAWES - 1996 - Interagency Information Sharing

-

Interagency Information Sharing: Expected Ben efit s , Manageable Risks

Sharon S. Dawes

Abstract The sharing of program information among government agencies can help achieve important public benefits: increased productivity; improved policy- making; and integrated public services. Information sharing, however, is often limited by technical, organizational, and political barriers. This study of the attitudes and opinions of state government managers shows that more than 8 in 10 judge information sharing to be moderately to highly beneficial. It also reveals specific concerns about the inherent professional, programmatic, and organizational risks. The study proposes a theoretical model for under- standing how policy, practice, and attitudes interact and suggests two policy principles, stewardship and usefulness, to promote the benefits and mitigate the risks of sharing.

INTERAGENCY INFORMATION SHARING: BENEFITS AND BARRIERS

Across the nation, public managers, elected officials, citizens, and businesses are seeking ways to redesign, streamline, and improve government operations and services [see, e.g., Osborne and Gaebler, 19923. Many initiatives are designed around the idea of service integration-a concept which often as- sumes a need to physically restructure organizations and processes. In the past, most such efforts have relied substantially on the reorganization of agencies and programs. Most have been expensive, and most have failed [Agranoff, 1991; Yessian, 1991; U.S. Department of Health and Human Ser- vice, 19831. The growing complexity of our society seems to defy structural reform.

Governments ever-growing store of information may offer an alternative way to deal with complexity [Strategic Computing, 1994; Andersen and Dawes, 19911. The information technologies of the 1990s offer a latent capac- ity to share information across agency and program boundaries, to discover patterns and interactions once hidden in millions of separate paper records, and to make decisions based on more complete data. For example, shared

Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Vol. 15, No. 3, 377-394 (1996) 0 1996 b the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management Publisheiby John Wiley & Sons, Inc. CCC 0276-8739/96/030377- I8

-

378 1 Interagency Information Sharing

Table 1. Categories of benefits and barriers associated with interagency information sharing.

Category Benefits Barriers

Technical Streamlines data management Incompatible technologies Contributes to information Inconsistent data structures

infrastructure

Organizational Supports problem solving Organizational self-interest Expands professional networks Dominant professional

frameworks

Political Supports domain-level action External influences over Improves public accountability decisionmaking Fosters program and service Power of agency discretion

coordination Primacy of programs

information could help different human services agencies view their common clinets as complete individuals of families rather than as unrelated sets of problems or needs [Andersen, Belardo, and Dawes, 19941. It could support comprehensive data for economic development, land use, infrastructure man- agement, or a host of other needs.

Despite such benefits, however, sharing is difficult to initiate or sustain. Discussions of information sharing almost always invoke turf, bureau- cracy, and power as reasons why agencies do not share information readily. These concepts are so pervasive and abstract that they present formi- dable obstacles.

BENEFITS

Proponents of information sharing can enumerate an extensive list of poten- tial benefits which offer advantages to policy makers, agencies, and the public (Table 1).

Technical Benefits

Streamlined Data Management. Sharing avoids duplicate data collection, processing, and storage and therefore reduces the heavy paperwork and data processing costs that attend every public program. By reducing and avoiding duplicate information handling, sharing improves productivity and can re- duce the overall cost of agency operations.

Information Infrastructure. To the extent that sharing encourages the devel- opment of technical standards, shared data centers, telecommunications net- works, metadata, and other technical resources, it helps to build an informa- tion infrastructure for government operations.

Organizational Benefits

More Comprehensive and Accurate Information for Problem Solving. Weiss [1987] found the pressure to solve internal problems to be a powerful incentive

-

Interagency Information Sharing f 379

for interagency cooperation. Because information is the foremost tool for problem solving, agencies benefit from cooperative activities that improye the quality, quantity, and availability of data. Comparing and augmenting internal agency data with external information can improve the accuracy and validity of the data in each agencys own programs. When information is compiled from several sources, the result is a more comprehensive picture of a problem or population. The agency is then in a better position to act effectively to achieve its program objectives.

Broadened Networks of Professional Contacts. The complexity and poten- tial for stalemate in the three-branch federal system demand that collabora- tive working relationships operate consistently at some level in order for the government to function. The behavior of experts in government is character- ized by building and maintaining networks of professional relationships [Heclo, 19771. The currency of these relationships is usually information about programs and the politics which surround them. Successful informa- tion sharing experiences reinforce these valuable professional relationships [Mosher, 1982; Wilensky, 19671.

Political Benefits

Broader Economic and Demographic Context for Programs. A collective infor- mation base helps the government and individual agencies identify and un- derstand broad economic and demographic trends leading to less insulated departments and a better appreciation for governmentwide policy goals. Sharing also supports more comprehensive identification and consideration of alternatives that in turn can improve budgetary and legislative delibera- tions regarding resource allocation decisions [U .S. Congress, Office of Tech- nology Assessment, 19931.

More Public Accountability and More Comprehensive Information for Pub- lic Use. Program information that is more complete and comprehensible to agencies can also be more valuable to the public, with direct benefits to those who depend on government information to make personal or business decisions. When program information is shared with the public, it forces government to be more accountable for its decisions [American Library Asso- ciation, 1986; Newcomer and Caudle, 19911.

Integrated Planning and Service Delivery. Combining or comparing the information of several organizations involved with the same people or prob- lems reveals overlaps, gaps, and interactions which no single organization may see on its own [Strategic Computing, 19941. Sharing existing data re- duces the information burden on program participants by cutting the number of times a person or organization must give the same information to different agencies and the number of times those agencies must reprocess duplicate information [Osborne and Gaebler, 19921. Sharing can lead to more accurate needs analysis, service definitions and planning, better program evaluation, and better integrated public services.

BARRIERS

Despite the potential benefits, successful interagency information sharing is difficult to achieve. A well-established body of research and experience sug- gests the following barriers to success (see Table 1).

-

380 1 Interagency Information Sharing

Technical Barriers

Incompatibile Hardware, Software, and Communications. The first barrier to sharing is technological incompatibility-the inability of different computer systems, networks, and software tools to talk to each other. Traditionally, computer manufacturers produced proprietary hardware to differentiate themselves and to attract and retain customers. The software that underlies applications systems is often custom-built or proprietary as well. Similarly, telecommunications networks often suffer from limitations that prevent orga- nizations from sharing information easily. Although so-called open systems and international standards are beginning to emerge, full technical compati- bility is still years away and remains a source of difficulty.

Mismatched Data Structures. Even in projects in which technology itself does not present barriers, sharing often remains problematic due to conflict- ing data definitions. For example, two units in a single organization may want to compare computerized information about the people receiving their services. Before they can accomplish this, however, they must both define and record key identifiers in the same way. A seemingly simple term like name or county can take many different forms and these differences can prevent effective sharing.

Organizational Barriers

Organizational Self-Interest. The self-interest concerns of individual organi- zations present another formidable barrier to information sharing. Because the benefits of organizational cooperation are often indirect and difficult to measure [Van de Ven, 19761, agencies will generally engage in cooperative action only when there is also some reasonable expectation of achieving self- interest goals [Van de Ven and Ferry, 19801. The relationships organizations develop with others may bring them considerable benefits, but they also create dependencies which exact a price in resources and lost autonomy [Pfeffer and Salancik, 19781.

Weiss [ 19871 identified three precursor conditions to interorganizational cooperation: the presence of a problem that would benefit from a cooperative solution; the existence of resources to address the common problem; and an institutional capacity to carry out a cooperative program. All three are necessary but not sufficient to cooperative action. Shared problems by them- selves do not launch cooperative solutions. An external catalyst is needed for cooperation to actually occur. Most commonly this takes the form of strong performance pressure, an active demand to do something [Weiss, 1987, p. 11 13. One powerful incentive is the need to solve a pressing internal problem. In other cases, a change agent or external crisis is needed to generate or crystallize issues, to mobilize a coalition, or to gain external support [Wam- sley and Zald, 19731.

Given all these factors, it is probably unreasonable to expect an organiza- tion to share its information resources without an expectation that it will gain internal benefits, improve its public image, or expand its influence over others.

Dominant Professional Frameworks. The emphasis on professional exper- tise is a key characteristic of bureaucratic organizations and is a second organizational barrier to information sharing. The overpowering influence of the professions in the public service has created what Mosher [ 19821 calls

-

Interagency Information Sharing 38 1

the professional state. The traditional professions (e.g., law, engineering, social work, medicine) set the standards for educational preparation and individual performance among the professional staff in agencies. The elite profession that is at the core of an agencys programs defines that agencys perspective on the world. Its ethical standards often dictate how information, especially information about people, may be used. Morevoer, that expert knowledge is a source of considerable power and stature [Lewis, 19801.

The professionals who work within agencies strive to impress their models of thinking and acting on the agencys programs. Each circle of experts shares assumptions, opinions, and core knowledge that is constantly reinforced by working within a closed system dominated by a single profession. As a result, specialists seldom consider program data for purposes beyond direct program operations [Wilensky, 19671, and few have used these data to analyze their own program performance [White, 19891.

Political Barriers

External Influences over Decisionmaking. One political barrier to information sharing centers on the complex web of influence over the decisions and deci- sionmaking processes of public agencies. These organizations share decision- making and implementation powers with a multitude of other powerful actors ranging from legislative committees [Warwick, 19751, to interest groups [Na- varro, 1984; Green, 19781, to the professions represented within the civil service [Mosher, 19821, to state and local officials who share responsibility for program operations and funding [Wright, 1978; Walker, 198 11. These interorganizational policy systems are loosely linked confederations of pub- lic and private organizations and individuals dependent on one another for resources and share an interest in certain classes of public policy [Milward, 19821.

This web of relationships exerts a constant pressure on agencies to attend to their direct constituencies, leaving little energy to devote to issues which transcend their boundaries or to build linkages with organizations outside the usual network.

The Power of Agency Discretion. A second political barrier is the drive to protect the policymaking power of administrative agencies. Executive departments have become a fourth branch of government with powers to shape and influence policy quite independently from the chief executive, legislature, and judiciary [Meier, 19791.

Because most programs are the product of inexact political compromises, they present ample opportunity for agencies to exercise both policy and administrative discretion [Pressman and Wildavsky, 1984; Moynihan, 19701. Agencies resist sharing information because information is a source of power and a symbol of their authority to make and implement decisions.

The Primacy of Programs. The primacy of programs [Rainey and Mil- ward, 19831 is a third political barrier to information sharing. Most govern- ment activity is defined and funded through legislation which creates specific programs and assigns responsibility for those programs to specific agencies. From an organizational perspective, programs reinforce vertical connections among the federal, state, local, and nonprofit agencies which deliver a particu- lar service to the public (e.g., Medicaid, drug abuse prevention, or highways). But these sharply defined program boundaries also act as barriers between

-

382 Interagency Informarion Sharing

agencies within a single level of government and, to some extent, create divisions within single agencies that administer multiple programs [Rainey and Milward, 19831. As a result, public officials see information as belonging to programs, rather than to agencies. They seldom regard program informa- tion as an asset of the whole agency, the entire government, or the public.

STUDY DESIGN

A 1990-1991 study in New York State sought to measure the extent to which the benefits and barriers suggested by the literature are reflected in the atti- tudes of practicing public managers. New York State agencies enjoy a high degree of autonomy in the way they use information resources. There is no central information management organization to oversee the actions of operating agencies. Information sharing projects develop out of the program- matic relationships between agencies, rather than from any central direction. This study focused on the shared use of program information produced or held by state government agencies. Program information included both paper- and machine-readable data that document the nature, content, and operation of public programs. Information sharing was defined to mean exchanging or otherwise giving other executive agencies access to program information. In all, 53 agencies were included in the study. The survey popula- tion consisted of 254 state government managers who are directors of informa- tion technology, research, planning, and mainline agency programs.

The self-administered mail survey achieved a 68 percent response rate (173 usable responses). A t least one person responded from all but one organiza- tion. Among the four professional job types, response rates were: 79.6 percent from information technology directors; 72.2 percent from research directors; 64.3 percent from program directors; and 62.5 percent from planning di- rectors.

Respondents were very experienced public managers, averaging 18 years of state service, usually concentrated in only one or two agencies. Respondents worked in agencies representing seven different policy groups: internal con- trol, economic affairs, education, general government, human services, infra- structure and environment, and law enforcement and criminal justice. Over 90 percent of the respondents had some direct experience in interagency information sharing projects, with 60 percent involved in a sharing project at the time of the survey.

The survey instrument consisted of several questions about the respon- dents experience with interagency information sharing; several demographic items; one open-ended question seeking commentary on sharing issues; and three sets of Likert-type scale items. The experience items asked how recently respondents had engaged in a sharing project and how much experience they had had with several kinds of sharing projects. These project types ranged from a simple project where one agency gives data to another for purposes of a particular program (like a social services department reporting welfare recipients wages to the tax department), to a very complex project where several agencies create a common data resource that they all use to conduct their programs (such as a computerized criminal history system used by all law enforcement and criminal justice agencies). The scale items measured: attitudes toward the benefits and barriers identified in the literature; opinions

-

Interagency Information Sharing 1 383

Table 2. Attitudes toward interagency information sharing.

Item Mean

1. Legislative or gubernatorial directives to share data in the interests of broad policy initiatives are needed

2. Sharing will strengthen existing relations with professionals in other agencies

3. Information sharing helps integrate the delivery of related public services

4. Sharing can enhance other forms of interagency relations 5 . Shared information contributes to the solution of multidimensional

public problems 6. One agency's information can help solve a program-specific

problem for another agency 7. Sharing data is a way to avoid unnecessary data collection 8. Outsiders better understand one agency's program in light of

9. Sharing is encouraged by personal knowledge about the information about the programs of other agencies

information resources of the state

information about the programs of other agencies

to respond

10. Agency staff better understand their own programs in light of

11. Sharing increases demands for access beyond the agency's capacity

12. Sharing diverts resources from other agency priorities 13. Differences between agency data sets causes political problems for

14. Shared data is misinterpreted or misused 15. The accuracy of validity of shared data will be challenged by other

16. Sharing invites unfounded criticism of programs by unsophisticated

17. Sharing erodes client confidence in agency programs 18. Sharing will encourage the substitution of political judgment for

19. Sharing is encouraged by personal knowledge about the

the involved agencies

agencies

outsiders

professional judgment in program decisions

information resources of one's own organization

5.74

5 S O

5.45

5.44 5.34

5.28

5.23 4.76

4.51

4.34

4.30

4.25 4.20

4.07 3.65

3.51

3.50 3.43

3.01

Note: 7 = strongly agree; 1 = strongly disagree.

about the importance of selected elements of sharing projects; and opinions about policies and tools used to govern sharing activities.

RESEARCH FINDINGS: ATTITUDES, CONCERNS, AND PREFERENCES

Attitudes Toward Interagency Information Sharing

Attitudes toward interagency information sharing were measured by asking respondents to agree or disagree with 19 statements about the usefulness of information sharing for problem solving, and about the benefits and problems sharing creates for the involved agencies. The full set of items and their mean scores are listed in Table 2.

Overall, respondents tended to agree that information sharing has a positive

-

384 1 Interagency Information Sharing

effect on problem solving and relationship building. They expressed strongest agreement with the ideas that information sharing supports broad policy initiatives, builds strong professional relationships, and supports integrated services. Weaker agreement was expressed about the ability of sharing to increase understanding of agency programs. Respondents also agreed that sharing would be encouraged by greater knowledge of statewide information resources, but not by better knowledge of their agencies own information.

On the negative side, respondents agreed that information sharing incurs administrative costs that may be unplanned or may divert resources from other activities. Their responses affirmed that shared data is misused and misinterpreted and that data discrepancies generate political problems for the involved agencies. There was also weak agreement that information shar- ing invities too many requests for access to agency data. Respondents did not agree, however, that sharing invites political interference in program management, that the accuracy of shared data is disputed, that sharing en- courages unfounded criticism, or that sharing weakens client confidence in agency programs.

A factor analysis was performed to identify the major components of atti- tude toward interagency information sharing. When grouped according to the factor solution, the survey items convey a broader underlying structure. Five key elements of attitude were suggested by the results. Respondents attitudes were influenced by the degree to which they perceived that sharing:

0 holds potential for solving domain-level problems; 0 reinforces valued relationships; 0 is aided by awareness of information resources; 0 threatens program integrity; and 0 generates costs to the participants.

Each of these attitudinal factors can be assigned to either a positive or a negative dimension. The problem-solving, relationship-building, and aware- ness factors have positive connotations. As a group, they represent the per- ceived or expected benefits of information sharing. The program-threatening and cost-related factors have negative implications and can be categorized as the perceived or expected risks.

To test whether these positive and negative groupings are valid ways to describe the dimensions of attitude, two additional seven-point scales were constructed and subjected to reliability analysis. The first scale, Benefits, consisted of individual survey items which loaded significantly on the three positive factors in the factor analysis. The second scale, Risks, consisted of items which loaded significantly on the negative factors.2 For each case,

I The factor analysis employed the principal components extraction technique and varimax rotation of the extracted factors. Individual items were considered to be associated with a factor if their loading on that factor was 0.40 or higher.

The results of the reliability procedures suggested that scale reliability would improve if one particular item was omitted from each scale. Accordingly, awareness of agency-level informa- tion resources was removed from the benefit scale and sharing weakens client confidence was removed from the risk scale. Removal of these items improved the reliability of each scale (Cronbachs alpha = 0.8423 for the benefit scale and 0.8171 for the risk scale), increased the number of cases for which both scores could be calculated (N = 1 1 S), and reduced the correlation between the scales (r = -0.1684, p > 0.05).

-

Interagency Information Sharing 385

I Individual survey items Factors Underlying dimensions 1 (3) Supports integrated services

(5) Helps solve complex problems

(1) Supports broad policy initiatives

(6) Improves my program (7) Avoids duplicate data

(8) Helps others understand my program

(10) Helps me understand my own program

(2) Helps pmfessional relations (4) Helps interagency relations

(9) Aided by knowledge of state info

(19) Aided by knowledge of agency info'

(1 3) Discrepancies cause political problems

(18) Invites political interference (1 5) Accuracy of shared data

is disputed (14) Shared data is

misinterpreted (16) Draws unfounded criticism :17) Weakens client confidence'

(12) Drains resources (11) Invites too many access

requests

Potential for solving domain-level problems -

Reinforcement of valued relationships

I I

Level of awareness

Benefits of interagency Information sharing

Threats to program integrity

Risks of interagency Information sharing

'Note: Omitted from final scale - see text note 2.

Figure 1. Translation of individual survey items into factors and underlying dimen- sions of attitude.

the risk score is the mean of the individual survey items which loaded on the negative factors; the benefit score is the mean of the individual items which loaded on the positive factors. In both scales the highest score is seven and the lowest is one. Figure 1 shows the correspondence of survey items to factors to underlying dimensions of attitude.

Some demographic differences were associated with the pattern of benefit and risk scores. Respondents with higher benefit scores tended to be female ( p < O.O5), to have had professional work experience outside state govern- ment, especially in an academic setting (both p < 0.05), to have had fewer

-

306 1 Interagency Information Sharing

Table 3. Distribution of benefit and risk scores.

Risk scores

Benefit scores High Low Total

High 33.1% 50.0% 83.1% Low 7.6% 4.2% 11.8% Total 40.7% 54.2%

years of service within state government, and to have had higher levels of formal education (both p < 0.01).

Higher scores on the risk scale were significantly associated with lower educational attainment ( p > O.Ol), an entire career spent in one professional specialty, a shorter term of service in the current agency, and past service in a larger number of different agencies (all p < 0.05).

In addition, higher scores on the benefit scale were significantly associated with more recent sharing experience, with greater amounts of information sharing experience, and with sharing experiences of greater complexity (all

Because most respondents answered all of the questions in both scales, it was possible to look at the intersection of their scores and to assess how they perceived both the risks and the benefits of sharing. A case plot was performed to graphically display the relationship between the two dimensions. Each individual was placed at the coordinates where his or her risk score and benefit score coincide. Table 3 summarizes the results. Table 3 displays a striking pattern. The vast majority of the respondents, more than 83 percent, scored in the upper half of the benefit scale while they were more evenly divided between the high and low segments of the risk dimension (40.7 percent and 54.2 percent, respectively). When the benefit and risk scores are matched for each respondent, we find that 50 percent viewed information sharing as a high benefit/low risk proposition and 33.1 percent viewed it as a high benefit/high risk undertaking. Very few cases fell into the lower (i.e., low benefit) quadrants of the plot.3 Cases whose scores fell exactly at the mid point of either scale are not shown in Table 3.

Since the Ns of the groups in the lower quadrants were so small (five cases and nine cases, respectively), they were discarded from further analysis. The two groups in the upper quadrants were the vast majority of the cases and they clearly agreed that sharing is beneficial. These groups were 1abeledconfident and cautious, implying that both groups recognized the benefits of sharing, but each group would approach it differently (i.e., confidently or cautiously) depending on how much risk they perceived to be attached to the sharing pro- cess. The confident group represents 60.2 percent and the cautious group repre- sents 39.8 percent of the cases used in the subsequent analyses.

There were two significant demographic differences between these groups.

Although 118 cases were plotted, 98 were used in the subsequent analyses. Six cases (5.2%) were discarded from further analysis since their risk scores Fell exactly at the neutral point (4.0). The t4 cases which were located in the two lower quadrants were also discarded because they represented groups that were t o o small to produce generalizable results.

p < 0.01).

-

Interagency Information Sharing 1 387

The confident group had substantially more doctoral level education than the cautious group. Twenty-eight percent of the confident group members held doctorates compared to 8 percent in the cautious group (chi-square, p < 0.05). Confident group members also had more recent interagency infor- mation sharing experience. Eight-four percent had experience that was no more than a year old. This was the case for 65.8 percent of the cautious group (chi-square p C 0.05).

Surprisingly, no significant differences were found between the two groups with respect to two other demographic characteristics. Neither professional affiliation nor agency policy type accounted for any statistically significant differences between the cautious and confident managers. The pattern of risk and benefit scores holds true regardless of membership in any of the four professional groups (program management, research, planning, and informa- tion services) or the seven agency policy types (internal control, economic affairs, education, general government, human services, infrastructure and environment, and law enforcement and criminal justice).

Confident and cautious managers gave very similar responses to the individ- ual survey items that make up the benefit scale. They assigned consistent and positive ratings to the potential benefits of sharing. There were no statistically significant differences on any of the 10 items. The two groups, however, differed significantly on every item in the risk scale. In each case, the cautious group saw substantial risks, whereas the confident group did not.

Members of the confident group were more likely to comment on the bene- fits of sharing-both for their own programs and for larger public policy needs. They often mentioned how shared information helps broaden the con- text for defining and analyzing issues and how it can free staff from tedious data collection tasks and allow them to spend more time on data analysis and problem solving. A respondent who scored 6.3 out of 7.0 on the benefit scale summed up the high benefit attitude in this commentary:

Except in specific instances where confidentiality is required or basic to program success, information should be readily available for sharing. The most important issues here are knowledge of what information is available, in what form, and how current and accurate it is; adequate resources to support an information system and an exchange network and mutual cooperation and assistance. The incentives to participate are long term cost reduction, [greater] efficiency, and a strengthened information base. The result is a more comprehensive ability to assess situations and develop program/project responses.

Many cautious respondents cited lack of common data definitions, inadequate planning and consultation about data use, and insufficient staff and technical resources as reasons why sharing efforts fail to achieve desired ends. They were also concerned about how shared data would be used and whether they could control or prevent misuse. The concerns or a respondent who scored 5.9 out of a possible 7.0 on the risk scale were stated in this way:

We need to know who will have access to the information and what it will be used for. Major costs include setting up an agreement, providing technical interpretation, organizing data into a translatable format, determining the accuracy of data received, and reviewing any summaries produced from the data.

-

388 1 Interagency Information Sharing

Table 4. Ratings of confident and cautious managers on the importance of selected elements of information sharing projects.

Variable

Extent of legal authority to share Need for expert data interpretation Potential to solve an internal program problem Administrative costs Involvement of outsiders

Confident group mean

6.02 5.98 5.46 4.95 4.19

Cautious group mean

6.49 6.35 5.95 5.62 5.34

p Value of t-test

< .05 < .05 < .05 < .05 . l o

Professional credibility of the other participants 5.51 5.65 >.lo Potential to solve anothers program problem 5.1 1 5.14 >.I0

multidimensional public problem

Note: 7 = extremely important; 1 = not at all important.

Planning and Defining Sharing Projects

In a second part of the survey, respondents were asked a set of questions about how information sharing projects are planned and defined. They rated the importance of eight items on a seven-point scale ranging from extremely important to not at all important. These items asked about the importance of expert data interpretation, the professional credibility of the participants, the potential for agency-specific and domain-level problem solving, the involvement of outsiders in agency programs, administrative costs, and legal authority to share information. As shown in Table 4, all the planning elements were considered important by both groups. There were significant differences, however, in the degree of importance expressed by each. The cautious and confident groups were in strong agreement about three of the eight elements. All managers confirmed that the potential to better understand a complex public problem was a powerful reason for undertaking an information sharing project. They also confirmed that i t would be worthwile to engage in sharing to help another agency with its programs. There was also strong agreement that the participants in the sharing process needed to have confidence in the professional credibility of their partners.

By contrast, the respondents displayed significant differences in their opin- ions about the importance of five of these eight elements. Cautious managers were far more concerned that information sharing might attract the un- wanted involvement of outsiders in their programs. These outsiders could be administrators from other program agencies, or, as indicated by many open-ended responses, from control agencies (such as a central budget office) that might exercise their own authority at the program agencys expense.

There were also differences between the two groups in the importance attached to legal authority. Cautious managers were more concerned that they have formal authority to share information outside their agencies. Most comments in this area were related to concerns for personal privacy and confidential treatment of sensitive information. These reflect reservations on two counts. First, that program clients and agency constituencies could suffer

-

Interagency Information Sharing 1 389

direct harm and, second, that general public trust in agencies and in govern- ment could be eroded.

The need for expert data interpretation was a third element of concern to cautious managers. Respondents cited the need for standard data definitions and for processes to resolve data discrepancies among different organizations. Several discussed their concerns ?bout poor information handling skills among the professionals and managers they work with and how these contrib- ute to misinterpretation and related problems. One noted, Most managers dont know the difference between data and information . . . [agencies pro- duce] infinite varieties of raw data with little or no explanatory material treating its meaning or usefulness.

Cautious managers were more concerned than their confident counterparts that information sharing should serve to solve their own agencys problems, not just help solve the problems of others. For this group, self-interest goals did not necessarily exclude mutual or external interests but it was clear that internal needs must figure prominently in any sharing arrangement. Some respondents cautioned that data sharing could become an end in itself unless it is related to a specific program goal. By contrast, those with a lower sensitivity to risk placed higher importance on solving an overarching domain-level problem.

Finally, cautious managers were more concerned about the administrative costs of information sharing. Many respondents cited unreimbursed adminis- trative effort as an important cost factor and barrier to information sharing. Some costs, such as programming and report preparation, are obvious and can be anticipated. Others are the byproduct of unexpected data or organiza- tional problems. One respondent reported in response to the open-ended question that the major cost is not the cost of information sharing itself, but the loss of time and resources (even when compensated) which would be normally applied to existing agency programs. He further noted that finan- cial compensation is of limited value because it cannot buy back the time or expertise of the experienced staff who were deployed to the sharing effort.

Preferred Forms of Authority

In a third set of scale items, respondents rated a set of nine hypothetical legislative proposals as a measure of their information sharing policy prefer- ences. The seven-point scale allowed for responses ranging from strongly oppose to strongly support. Four of the nine proposals had to do with the nature of authority to share. These ranged from the most permissive (general authority to share unless specifically prohibited) to the most restrictive (gen- eral prohibition against sharing unless specifically authorized).

As Table 5 shows, the preferred form of authority for both groups was the most permissive form-general statutory authority to share. General authority imparts legitimacy without mandating process. It is the most basic legal foundation for any agency action. Correspondingly, both groups strongly opposed the reverse proposal, a general prohibition against sharing. The two groups differed significantly, however, on the two other choices. While both opposed requiring specific legislation for each sharing project, the cautious group was significantly less opposed. On the matter of a mandatory inter- agency agreement to govern each project, the groups had opposite opinions. The confident group opposed this proposal; the cautious group supported it.

-

390 1 Interagency Information Sharing

Table 5. Preferences of confident and cautious managers regarding nature of authority to share information.

Variable

Confident Cautious group group p Value of mean mean t-test

Require a specific interagency agreement 3.09 4.26 co.01 for each sharing project

each sharing project Require specific legislative authority for 1.87 2.54 0.10 General legislative prohibition except where 1.58 1.92 >0.05

sharing is specifically authorized

Note: 7 = strongly support; 1 = strongly oppose

Both groups clearly wanted the legislature to affirm that their agencies have explicit authority to share information. The permissive nature of general legislative authority-the kind of statute whose operative term is agencies may rather than agencies shall-had universal appeal. It offers both legiti- macy and the flexibility to deal with the widest variety of information sharing opportunities and concerns.

As the above response pattern suggests, however, the confident group would be likely to use this authority to legitimize independent judgment. The cau- tious group would probably use it to create, through interagency agreements, a more formal and structured environment for sharing activities. In either case, the final form of a sharing project would be agency-determined. But, in the first case, that determination would rely more heavily on professional judgment and informal relationships. In the second, it would rest more on formally stated rules and fixed assignment of organizational responsibilities.

Preferred Management Tools

Five other hypothetical legislative proposals had to do with the creation of or obligation to use specific management tools in the process of sharing. These included: statewide and agency information inventories; common data definitions; technical standards for electronic data; and an information clear- inghouse mechanism. In every case, the mean response was positive. Like the items in the benefit scale, the management tools represented a related set of items for which there was no statistically significant difference of opinion between the two groups. Whether their approach to information sharing was cautious or confident, state managers uniformly said that they needed better practical tools to support it.

DISCUSSION: ACHIEVABLE BENEFITS, MANAGEABLE RISKS

This concluding discussion reviews the benefits and risks of sharing; outlines a general theory of interagency information sharing; and makes related rec- ommendations for policy, practice, and future research.

-

Interagency Information Sharing 391

Promote benefits

Pressing Expected . oroblem benefits information sharing Expected

risks

I Actual benefits

d Actual risks

Mitigate risks

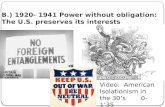

Figure 2. Theoretical model of interagency information sharing.

The Benefits and Risks of Interagency Information Shoring

The respondents in this study agree on the benefits of interagency information sharing. Although they represent different kinds of agencies and different professions, more than 8 in 10 respondents judged information sharing to be moderately to highly beneficial. Responses to both structured and open-ended questions produced an impressive list of benefits heavily weighted with expec- tations that information sharing can help solve both agency-specific and domain-level problems. Respondents said that sharing supports better, more integrated planning, policy development, and program implementation across agencies; contributes to more comprehensive and accurate informa- tion for decisionmaking and problem solving; makes more productive use of increasingly scarce staff resources; and helps build positive interagency and professional relationships. The data also show that the more experienced respondents were more likely to recognize and endorse these benefits.

The study also shows that a sizeable minority of these same managers (40 percent) are concerned about professional, programmatic, and organizational risks. According to this group, sharing can tend to discount the concentrated expertise and superior knowledge of policy professionals and therefore limit their discretion to make policy and program decisions. Because program information is complex and context-sensitive (and therefore easy to misinter- pret), they are reluctant to open it to a larger group of users and potential critics. Sharing is also a resource drain. It competes with internally driven demands for agency-specific resources while returning benefits that the agency must share with others. The study showed that the most risk-sensitive respondents tended to have less formal education, less variety in their profes- sional backgrounds, and shorter assignments in a larger number of agencies.

Finally, we have seen that public managers want a legal framework and formal policies to guide information sharing decisions and activities. They also uniformly want effective tools for managing public data and or sharing it effectively.

Taken together, the descriptive and analytical results of this study suggest a theoretical model for understanding interagency information sharing (Fig- ure 2). The study suggests that the pressure to solve an important public problem stimulates the use of information sharing. It also suggests that past

-

392 Interagency Information Sharing

sharing experience makes a difference in expectations about the benefits and that formal policy and management supports may mitigate the risks. The interaction of expectation, experience, and institutional supports appears to work in the manner shown in Figure 2.

This simplified model outlines what appear to be the main factors. A press- ing public problem is identified as a suitable candidate for information shar- ing. The participants enter the sharing experience with preconceived ideas about the benefits the experience will produce. They also have prior expecta- tions about the risks to which they, their programs, and their agencies will be exposed. The sharing process itself is influenced by the characteristics of the policy and management environment in which it is conducted. Sharing experiences produce actual benefits and actual risks which modify the expec- tations managers have for future sharing projects. Experience also produces lessons about how well the projects achieve their goals and how well they manage or avoid expected risks. To the extent that these lessons influence general sharing policies and management tools, they will shape future prac- tice, promote future benefits, and mitigate future risks. If the connection between experience and policy refinement is weak, sharing will continue to be an ad hoc practice, shaped largely by the experiences and expectations of the current participants. If the connection is strong, however, sharing can become a more formal, refined tool for public management.

Policy Principles

If the theory is correct, information sharing policies should help create an environment in which sharing is an effective, legitimate activity of public agencies. But the needed framework will not emerge automatically. Executive and legislative action are required. Government must adopt fundamental policy principles that will help agencies decide when sharing is appropriate, and must create standards and services that will help make sharing success- ful. A manager from an infrastructure and environment agency summarized these needs quite well:

In my estimation the most important information sharing issues are ( I ) legal context for sharing, (2) technical infrastructure and standards for sharing information, and (3) administrative structure for organizing sharing efforts and developing information policy. My sense is that (with these in place) the benefits could exceed any of the costs associated with a well-targeted sharing effort. . .

Successful sharing depends on an information policy which takes a global view of how information resources can support government services. It should convey an affirmative expectation that government information be used to increase knowledge, improve analysis, and inform decisions as well as to administer programs.

Any jurisdiction seeking the benefits of interagency information sharing must adopt policies which do more than simply make sharing possible. It needs policies which make it probable that appropriate problems will be identified and that reasonable effort will lead to success. Two such policy principles are suggested by this study:

Information Stewardship. A stewardship principle views agencies as stewards

-

Interagency Information Sharing / 393

of government information, not owners. Stewardship focuses on the accuracy, integrity, and preservation of information holdings. It does not fix a single point of responsibility for such issues as accuracy, validity, security, use, description, or preservation. Instead, stewardship conveys the idea that every government organization is responsible for handling information with care and integrity, regardless of its original source. It demands that government information be acquired, used, and cared for as a jurisdiction-wide resource. Information Use. A second policy principle would encourage information use. It would emphasize the value of information as a corporate asset or collective resource capable of and available for a wide variety of uses within the govern- ment. It would give agencies incentives to share data and other information resources; it would encourage investment in the information processing, anal- ysis, and presentation skills of the public workforce; and it would lay the foundation for organizational and financial mechanisms to support informa- tion sharing.

The stewardship and usefulness principles reinforce one another. Better stew- ardship should produce more reliable, more useable information. Better infor- mation should inspire greater confidence, which in turn should lead to more frequent and more effective information use.

In this study, the confident managers appear to place a high value on the implicit principle of information use. They understand the value of informa- tion content and focus most strongly on the benefits sharing can produce. They tend to think of information as a government-wide resource to be used wherever it can add value to public policy or program operations. The cau- tious managers illustrate the equally important stewardship principle. Their concerns for accuracy, integrity, context, cost, and legitimacy are reasonable and worthy of formal policy attention. These policy principles and the pro- posed theoretical framework offer guidance to both policymakers and prac- titioners. Together, they can help government reduce the barriers and achieve the benefits of information sharing.

SHARON S. DAWES is Director of the Center for Technology in Government, University at Albany, State University of New York.

REFERENCES

Agranoff, Robert (1991), Human Service Integration: Past and Present Challenges in Public Administration, Public Administration Review 51(6), p p . 533-542.

American Library Association ( 1 986), Freedom and Equality of Access to Information (Chicago: American Library Association).

Andersen, David F., Salvatore Belardo, and Sharon S. Dawes (1994), A Framework for Strategic Information Management in the Public Sector, Public Productivity and Management Review (Summer), p p . 335-353.

Andersen, David F. and Sharon S. Dawes (1991), Government Infomzation Management: A Primer and Casebook (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall).

Green, Mark J. (1978), The Other Government: The Unseen Powerof Washington Lawyers, Rev. ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co.).

Heclo, Hugh (1977), A Government ofstrangers: Executive Politics in Washington (Wash- ington, DC: The Brookings Institution).

-

394 I Interagency Information sharing

Lewis, Eugene (1980), Public Entreprenauship (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press). Meier, Kenneth J. (1979), Politics and the Bureaucracy: Policy Making in the Fourth

Branch of Government (North Scituate, MA: Duxbury Press). Milward, H. Brinton ( 1 982). Interorganizational Policy Systems and Research on

Public Organizations, Administration and Society 13(4), pp. 457-478. Mosher, Frederick C. (1982) Democracy and the Public Service, 2nd ed. (New York:

Oxford University Press). Moynihan, Daniel P. (1970), Maximum Feasible Misunderstanding (New York: The Free

Press). Navarro, Peter (1984), The Policy Game: How Special Interests and Ideologues are

Stealing America (New York: John Wiley & Sons). Newcomer, Kathryn E. and Sharon L. Caudle (1991), Evaluating Public Sector Infor-

mation Systems: More than Meets the Eye, Public Administration Review 5 l(S), pp. 377-384.

Osborne, David and Ted Gaebler (1992>, Reinventing Government (Reading, MA: Addi- son-Wesley).

Pfeffer, Jeffery and Gerald R. Salancik (1978), The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective (New York: Harper & Row).

Pressman, Jeffrey and Aaron Wildavsky ( 1 984), Implementation, 3rd ed. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press).

Rainey, Hal G. and H. Brinton Milward (1983), Policy Networks and Environments, in Richard H. Hall and Robert E. Quinn (eds.), Organizational Theory and Public Policy (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications).

Strategic Computing and Telecommunications in the Public Sector (1994), Customer Service Excellence (Cambridge, MA: John F. Kennedy School of Government, Har- vard University).

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment ( 1 993), Making Government Work: Electronic Delivery of Federal Services (Washington, DC: U .S. Superintendent of Docurnen ts) .

U S . Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Program Development (1983). A Review of the Conceptual Foundations and Current Status ofservice Integra- tion (Washington, DC: US. DHHS).

Van de Ven, Andrew H. (1976), On the Nature, Formation, and Maintenance of Relations among Organizations, American Management Review 1(4), pp. 24-36.

Van de Ven, Andrew H. and Diane Ferry (1980), Measuring and Assessing Organizations (New York: WiIey).

Walker, David B. (1981). Toward a Functioning Federalism (Cambridge, MA: Wintrop Publishers).

Walmsley,Gary and Meyer N. Zald (1973). The Political Economyof Pubtic Organiza- tions, Public Administration Review 33, pp. 62-73.

Warwick, Donald P. (1975), A Theory of Public Bureaucracy: Politics, Personality, and Organization in the State Department (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Weiss, Janet A. (1987), Pathways to Cooperation among Public Agencies, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 7 (Fall), pp. 94-1 17.

White, Louise (1989), Public Management in a Pluralistic Arena, Public Administra- tion Review 49(6), pp. 522-532.

Wilensky, Harold L. ( 1 967), Organizational Intelligence: Knowledge and Policy in Gov- ernment and Industry (New York: Basic Books).

Wright, Dell (1978), Understanding Intergovernmental Relations (North Scituate, MA: Duxbury Press).

Yessian, Mark R. (1991), Services Integration: A Twenty-YearRetrospective (Washington, DC: US. DHSS, Office of the Inspector General).