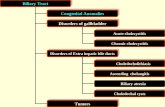

Congenital Absence of the Gallbladder

Transcript of Congenital Absence of the Gallbladder

Canad. Med. Ass. 3.July 17, 1965, vol. 93 CASE REPORT: CONGENrrAL ABSENCE OF fliF GALLBLADDER 123

Congenital Absence of the GallbladderEARLE WRIGHT, M.D.0 and PATRICK MADORE, M.D., Montreal

THE gallbladder has an irregular distribution inkingdom. It is present only in

vertebrates, being constant in amphibians andcarnivores but variable in fish, birds and herbivores.In the horse, camel and deer the organ is normallyabsent, while in the giraffe and elephant congenitalabsence of this structure is frequent. In the pigeonthe gallbladder is present in embryonic life butdisappears with later development.1

Congenital agenesis of the gallbladder in humansis extremely uncommon. An exact incidence is diffi-cult to determine, but some idea of its rarity isobtained from the fact that up to 1962 only 140authenticated cases have been reported in theworld literature. In approximately half of these theanomaly was an incidental finding at autopsy. Thisanomaly is generally accepted as being the resultof defective embryological development of the bili-ary bud. There is also a distinct possibility that ahereditary factor is implicated; Kobacker2 reportedthe condition in two sisters, and cholecystogramsfailed to demonstrate the gallbladder in three outof five other siblings in this family.

In view of the rarity of the condition and itsclinical significance, our experience with a recentcase of congenital absence of the gallbladder en-countered at laparotomy is presented and certainpertinent aspects of this anomaly, ascertained by areview of the literature, will be discussed.

A 50-year-old white woman was admitted becauseof right upper abdominal pain of three days' duration,associated with nausea and vomiting. She had sufferedperiodic attacks of a similar nature since 1958. Twoprevious cholecystograms carried out in 1958 and 1962had failed to demonstrate the gallbladder. There was nohistory of jaundice, and the family history was notcontributory. A hysterectomy and appendectomy hadbeen performed elsewhere 10 years before. The solepositive physical finding was slight tenderness in theright upper quadrant of the abdomen. An oral gall-bladder series revealed non-visualization of the gall-bladder without evidence of calculi (Fig. 1). A bariummeal examination, barium enema, intravenous pyelo-gram and an electrocardiogram were all normal.The association of the symptoms with the radiological

finding of a "non-functioning" gallbladder led to adiagnosis of chronic cholecystitis. Laparotomy was per-formed through a right subcostal incision. The gall-bladder fossa was not developed, and neither a gall-bladder nor cystic duct could be identified after carefulsearch which included the usual ectopic locations. The

From the Department of Surgery, St. Mary's MemorialHospital. Montreal. Quebec.*Chief Resident, St. Mary's Memorial Hospital.

SFig. 1.-Oral cholecystographic series revealing non-visuali-

zation of the gallbladder without evidence of calculi.

common bile duct was not dilated or indurated, and nostones could be palpated. An operative cholangiogramwas performed by direct injection of the dye into thecommon duct through a No. 22 gauge needle, afteraspiration had revealed clear yellow bile. Good visualiz-ation of the common duct and its hepatic branches wasobtained. There was no evidence of a cystic duct orgallbladder. Dye flowed freely into the duodenum andno biliary stones were noted (Fig. 2). In view of thelack of any demonstrable pathology it was decided notto explore the common bile duct. A liver biopsy per-formed with a Vim-Silvermann needle revealed normalfindings. The postoperative course was uneventful. Thepatient has been asymptomatic for three months sinceoperation.

DIscussIoNSeveral matters of clinical interest are illustrated

by the foregoing case and by other cases reportedin the literature. The diagnosis of congenital ab-sence of the gallbladder cannot be made preoperatively, except possibly in the rare familial casewhen it might be suspected. Approximately one-half of the patients with this anomaly have had alaparotomy performed because of a diagnosis ofchronic cholecystitis. This diagnosis was based onthe association of symptoms suggestive of biliary

124 CAsE REPORT: CONGENITAL ABSENCE OF THE GALLI3LADDER Canad. Med. Ass. J.July 17, 1965, vol. 93

duct has been found to be hypoplastic1' and thisprobably represents an associated developmentaldefect related to congenital atresia of the bile duct.The high incidence of biliary symptomatology,

jaundice and common duct stones is difficult toexplain. Pribram5 has noted that some cases ofcholecystectomy are followed by pressure changesin the bile ducts, disturbed kinetics of the sphincterof Oddi and altered biliary drainage. These changesmay become clinically manifest as colicky abdomi-nal pain, flatulence and fatty food intolerance. Thiswould explain cases of the so-called postchole-cystectomy syndrome and biiary dyskinesia inwhich residual pathology, such as overlookedcalculi, has been ruled out.The presence of common bile duct stones in

almost a third of the cases of congenital agenesisof the gallbladder provides convincing support forthe theory that stones can develop de novo outsidethe gallbladder. Factors which favour calculusformation include changes in the chemical composi-tion of the bile, though in most cases a combinationof factors is responsible. Cholecystectomy is fol-lowed by a rise in blood lipids,6 but there are nodata available on blood lipid concentration in pa-tients with congenital absence of the gallbladder.An additional factor in these cases may be bilestasis, as increased tonus of the sphincter of Oddican produce mechanical obstruction and biliaryretention.7 8 The physiological purpose of thesphincter of Oddi in individuals with congenitalagenesis of the gallbladder is *unknown, butsphincter dysfunction in these cases may exist andproduce biiary stasis. In view of the alreadymentioned fact that animals that do not have agallbladder also lack a sphincter of Oddi, the merepresence of such a sphincter in humans born with-out a gallbladder may be a physiological liability.The high incidence of jaundice in these persons isa reflection of the frequency of common duct stones.It has been reported, however, that obstructivejaundice will develop far more readily after removalof the gallbladder.9 With congenital absence of thisviscus, milder degrees of obstruction may produceclinical jaundice than in the normal person. Atoperation the problem can present difficulties. Be-cause of the rarity of the condition, treatment isnot standardized. It is essential to ensure first thatone is indeed dealing with congenital absence ofthe gallbladder. With the exception of a previouslyexcised gallbladder, the most likely causes of ap-parent absence are an atrophic organ buried inadhesions, an intrahepatic location, and a left-sidedgallbladder. For absolute confirmation an operativecholangiogram is a necessity. This is also of valuebecause of the frequent association with biiarycalculi. The associated pathology will dictate themeasures subsequenUy carried out. Obvious indica-tions for common duct exploration are the presence

Canad. Med. Ass. J.July 17, 1965, vol.93 CASE REPORT: CONGENITAL ABSENCE OF THE GALLBLADDER 125

of stones, duct dilatation and jaundice. Contrari-wise, in the absence of these indications the hypo-plastic type of duct should definitely not be ex-plored, since there is a considerable risk of produc-ing duct trauma and resulting biiary stricture.Mann10 has recommended transduodenal sphinc-terotomy because of the possibility of functionalobstruction at the sphincter of Oddi. This is acontroversial point, and few surgeons seem willingto perform such a procedure without more definiteevidence that such an obstruction is a reality.There has not been long-term follow-up in a

sufficient number of these patients to assess theresults of surgical and conservative treatment. Atthe present time the exact disturbances in dynamicsand physiology which predispose to biiary ductdisease in these cases are not clear.

SUMMARY

A case of congenital absence of the gallbladder isreported. This is an extremely rare anomaly. The diag-nosis was confirmed at laparotomy by means of anoperative cholangiogram.

This anomaly is frequently associated with ana-tomical, physiological and pathological derangementsof the remaining biliary system.The similarity of the symptom complex in these cases

to those occurring in functional biliary dyskinesia andthe postcholecystectomy syndrome supports the argu-ment that the latter conditions are real clinical entities.The underlying pathophysiology which predisposes

to biliary disease in these cases has not yet been eluci-dated.The surgical treatment depends on the associated

biliary pathology. The role of sphincterotomy in thiscondition is still controversial.

REFERENCES

1. MENTEER, S. H.: J. A. M. A., 93: 1273, 1929.2. KOBACKER, J. L.: Ann. Intern. Med., 33: 1008, 1950.3. DixoN, C. F. AND LICHTMAN, A. L.: Surgery, 17: 11. 1945.4. LICHTMAN, S. S.: Diseases of the liver, gallbladder and

bile ducts, vol. 2, 3rd ed., Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia,1953, p. 1180.

5. PRIBRAM, B. 0. C.: J A M A 142: 1262, 1950.6. ATKINSON, A. J. AND Ivy, A. d.: J. Lab. Olin. Med., 23:

441, 1938.7. BEST, R. R. AND HICKEN, N. F.: Surg. Gynec. Obstet., 61:

721, 1935.8. Ivy, A. C. AND SANDBLOM, P.: Ann. Intern. Med., 8: 115,

1934.9. MANN, F. C. AND BOLLMAN, J. L.: J. Lab. Olin. Med., 10:

540, 1925.10. MANN, A. S.: Och.sner Olin. Rep., 3: 30, 1957.11. WEDER, C. H.: Oanad. J. Sury., 5: 446, 1962.

PAGES OUT OF THE PAST: FROM THE JOURNAL OF FIFTY YEARS AGO

SYPHILIS OF THE HEART AND AORTAOf the advances in modern medicine few are of more

importance than those which have been made in ourknowledge of the morbid changes and symptoms causedby syphilis of the vascular system. Syphilis has been knownas a cause of aneurism for over two centuries, but it islittle more than half a century since it was shown to bea cause of arteritis. In 1856 Sir Samuel Willcs first drewattention to syphilitic affection of the heart, and in 1868Sir Clifford Allbutt gave the first description of the histo-logical changes of syphilitis of the arteries. The knowledgeof the subject increased rapidly, but it was not until thediscovery of the Treponema pallidum as the infectingorganism causing the disease that the great importance ofvascular syphilis came to be fully realized. It is probablythe most common cause of disease of the arteries, and ofthe heart it is at least only second to rheumatism. Aneurismoccurring before middle life is nearly always due to syphilis,and very often after also, if we exclude the later years oflife. In many cases no history of infection, or of symptomsdue to it, can be dbtained. It is of great importance to befully alive to this possibility in all cases, even in thosewith a history of rheumatism. The Wassermann test maysettle the matter. If there is syphilis in other structures,or the existence of disease at least frequently due tosyphilis, suc.h as tabes dorsalis, the syphilitic nature of thecardiac or arterial disease may usually be taken for granted.

Syphilitic lesions of the heart and aorta produce symp-toms identical with those arising from lesions in the sameparts from other causes. The invasion of the auriculo-ventricular bundle by a gumma, or fibrosis secondary tocoronary arteritis, is probably the most frequent cause ofheart-block Praecordial distress is common, and so isangina pectoris in cases in which there is sclerosis of theaorta and heart.

Next to prophylaxis early, vigorous and persistent treat-ment is of the greatest importance. Such treatment shouldcure every case. It is important to keep before our mindsthat the disease is caused by an infecting organism, the

Treponema or Spirochoeta pallidum, atid that it can bedestroyed in the blood and tissues by mercury, and byarsenic given in the form of diarsenol. The treatmentshould be continued until we are assured the organisms areall destroyed as shown by the Wassermann test. Even afterthe test gives no reaction the treatment should be con-tinued for several months less vigorously, with graduallylengthening intervals between the courses, and the testapplied at intervals to ensure the continued absence of thereaction. At the same time the general health should bemaintained in the best possible condition. If such a coursewere pursued in every case there would be in time nosyphilis nor cardio-vascular disease arising from it. The facts a so be emphasized that jodides in any form haveno effect on the virus of syphilis; they only affect theexudate arising from it; in this respect they are of greatbenefit, even in the early stages.

After the later signs of the disease manifest themselvesthe same course of treatment should be carried out andwith the greatest possible efficiency. With the giving ofmercury and cliarsenol to destroy the spirochaete, andiodide of soda or potash to promote absorption of anyexudate that may have formed, the outlook in earlier casesis good, and even in late cases it is not hopeless; therewill be improvement in most of the latter and they maybe restored to live a comfortable and useful life.The prophylaxis of the disease does not come within

the scope of this paper. It is a matter of the greatest im-portance to the pt.blic health of the country as the num-ber of the infected is increasing rapidly. Many of the im-migrants are infected and many of their children show theevidences of the disease. Those people are a grave menaceto the communities in which they settle. They constitute aconsiderable proportion of our hospital population, especi-ally in the larger cities, and are therefore a great burdenon our charitable funds. The matter calls for action by thegovernment, as it is quite as important that those infectedwith syphilis, as with tuberculosis, be excluded from thecountry.-Alexander McPhedran, Canad. Med. Ass. J., 5:680, 1915.