195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

Transcript of 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

1/48

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

2/48

VACATION GUIDEDESERT RESORTS DESERT EVENTS GUIDED DESERT TRIPS

By February the 1955 desert sea-son will be well under way. Whynot become a part of it this year?Here are some suggestions on whatto do and where to stay on yourdesert holiday.

FURNACECREEK INNAMERICAN PLAN

FURNACE CREEKR A N C H /EUROPEAN PLAN ..!

Enjoy this luxurious desert oasisfor rest, quiet, recreation: golf,tennis, riding, swimming, tour-ing, andexploring. Sunny days,cool nights. Excellent highways.For folders and reservationswrite 5410Death Valley HotelCo., Death Valley, Calif. Orphone Furnace Creek Inn atDeath Valley. Orcall vour localtravel agencies.

S A N J U A N and C O L O R A D ORIVER EXPEDITIONSEnjoy exploralion safe adventure andscenic beamy in the gorgeous ccnyons olUtah and Arizona. Slrrinch boas, experi-enced rivormen. For I'sb5 summer scheduleor charier trips anytime write toJ . FRANK WRIGHTMEXICAN HAT EXPEDITIONSBlanding. Utah

Confirmed or ProspectiveRIVER RATSS H A R E THEEXPENSEEASTER WEEK SPECIALon Glen Canyon-Sunrise EasterService on South Rim of CanyonApril 2 through April 9

Phone PLY 5-3125Write to:GEORGIE AND WHITY

737 W. 101st STREETLOS ANGELES 44, CALIF.

GREEN PALM LODGEDON and ELIZABETH McNEILLY(Resident Owners)Hwy. I l l , Palm Desert, Californiamidway between lndio andPalm Springs.All Electric AccommodationsRooms andFully Equipped ApartmentsComplimentary BreakfastServed to your room or around Pool. Pooltemp, above 80 at all times. Beautifulscenery in a warm dry climate.Only few minutes from where PresidentEisenhower plays golf. Close to fine res-taurants, entertainment, golf, tennis,horses, shops. Members of fabulousShadow Mountain Club.(Rec. by So. Calif. Auto ClubNat. AutoClub. Also in most Blue Books.)For Reservations: Write P.O. Box 212,or phone Palm Desert 76-2041

SCOTTY'S LCASTLE Mi

DEATHVALLEY

HOURLY TOURSOF FABULOUS LUXURY

Overnight Accommodations:European from $6 dbl.M o d . Am. from $13 dbl.See your Travel Agent

or writeCASTLE HEAD OFFICE

1462 N. Stanley AveHollywood 46, Calif.NOW IS THE TIME

Home of the Famous AnnualBURRO-FLAPJACKCONTEST

Stove Pipe Wells Hotel wasuntil hisdeath in 1950owned andoperated byGeorge Palmer Putnam, renownedauthor andexplorer. It continues un-der the personal management of Mrs.George Palmer Putnam.Season: October 1 to June 1

M O T E L C A L I C OIs located in the cen ter of an area that helped make California his tory ,from 1880to 1896.T H I S IS A P H O T O G R A P H E R S P A R A D I S E9 miles East of Barstow, California, on H i g h w a y 91,at Daggett RoadFROM MOTEL CALICO IT IS:S Mi. to Silver Ores tam p mil l ru in s (Operated from 1880 to 1893)3.5 Mi. to Kn ott ' s Calico Ghost Town (Mining town being res tore d)3.5 Mi. to His to r ica l old cemeter ies4 Mi. to Odessa Canyon . . . (Original old s i lver mine t ipples s t i l l s tanding)4.5 Mi. to Mule Canyon (Original Bor ax Mines s t i l l ther e)7 Mi. to Sunr i se Canyon . .(A bri l l iant ly colored miniature Grand Canyon)15 Mi. to Fossi l Beds (TheFamous Pictorial l iOop)Pisgah Crater Volcano Close ByBRING YOUR CAMERAS AND S L I D E S(Projector and Screen furnished by the m a n a g e r )Z people $5.00 per n igh t 4 people $0.50 per n igh tPet's $3.00 extraElec t r ic k i tchens ava i lab le . You r e s t in quiet , insulated, ai r cooled andind iv idual ly hea ted un i t s . In fo rmat ive b rochure mai led on r e q u e s t .Phone Barstow 3467 Box 6105,Yermo, California

Greatest Festivaland Pageant in theDesert Southwest!6th Annual InternationalDESERTCAVALCADEof Imperial Valley

3 pleasure-packed days March 18, 19. 20. 1955

CALEXICO. CALIFORNIAAt this sunny border community peopleof two nations cooperate in the presenta-tion of a thr il l ing, authentic spectacle.Join in the festivities with friendly,thriving Imperial Valley as your host. Takea winter holiday in this desert agriculturalempire. Convenient modern accommoda-tions available.For reservations or free il lustrated bro-chure write now toDESERT CAVALCADEP.O. Box 187, Calexico, California

Stove Pipe Wells HotelDeath ValleyCalifornia

D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

3/48

D E S E R T C A L E N D A RThrough FebruarySpecial exhibit ofhistorical buildings of Californiaand portraits of personages notedin the State's history, SouthwestMuseum, Los Angeles.February 3Big Hat Day, opening1955 Rodeo Season, Tucson, Ari-February 3-5 Cattlemen's Conven-tion, Yuma, Arizona.February 3-6 Phoenix Open GolfTournament, Phoenix, Arizona.February 5-6Palm Springs AnnualWinter Western Celebration. Cali-fornia.February 5-6Sierra Club, RiversideChapter, hike into Anza DesertState Park, California.February 5-6Sierra Club CampingTrip into Cathedral Canyon, ArabyTrail, Cathedral City, California.February 6Don's Club Trip to Je-rome and Montezuma Castle, Phoe-nix, Arizona.February 7-13 Southwestern Live-stock Show and Rodeo, El Paso,Texas.February 12 Palm Springs DesertMuseum Field Trip to Wildcat Can-yon, near Palm Desert, California.Febru ary 12 Dedication of SaltonSea California State Park; all daypicnic with program.February 12-13Jaycee Silver SpurRodeo, Yuma, California.Feb ruary 17-22 Riverside Coun tyFair and National Date Festival,Indio, California.February 19 Palm Springs DesertMuseum Field Trip to MurrayCanyon, tributary of Palm Canyon,California.February 19-20Wickenburg HorseShow, Arizona.February 19-27 Maricopa CountyFair, Mesa Civic Center, Mesa,Arizona.February 20-March 6Southwest In-dian Arts and Crafts, Fine ArtsGallery, Tucson, Arizona.Februar y 24-27 Fiesta de L osVaqueros, Tucson, Arizona.February 26-27Sierra Club Camp-ing Trip, Thousand Palms, Pusha-walla Canyon, California.February 26 Palm Springs DesertMuseum, California, Field Trip.February 27 Don's Club AnnualTrek for Lost Gold in SuperstitionMountains, from Phoenix, Arizona.

DtAtfiL

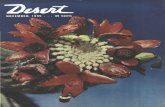

V o l u m e 18 F EBRU AR Y . 1955 N u m b e r 2C O V E R

C A L E N D A RF O R E C A S TBIRDSE X P L O R A T I O NN A T U R EHIKINGFIELD TRIPC O N T E S TC L O S E - U P SP H O T O G R A P H YEXPERIENCEDESERT QUIZR E C R E A T I O NLETTERSW I L D F L O W E R SF ICTIONP OETRYM I N I N GN E W SPRIZESH O B B YL A P I D A R YC O M M E N TB O O K S

The desert is a thirsty place. Badwater Billpauses at a waterhole, Death Valley, Cali-fornia. Photo by JOSEF MUENCH of S ant aBarbara, California.Febru ary events on the desert 3Tom orrow 's Desert, by HULBERT BURROUGHS . 4The Humm ingbird Cafeteria 8Cattle Ranch Among the PalmsBy RANDALL HENDERSON 9Scavengers of SonoraBy EDMUND C. JAEGER 12Three Tries to the Top of the Whipple RangeBy LOUISE T. WERNER 14Agate Hunters in the ApachesBy GILBERT L. EGGERT 18Prizes for desert pho togr aph s 20About those who write for Desert 20Pictures of the Month 21Life on the Desert, by TOM MAY 22A test of your desert know ledge 23Dwelling Place of the AncientsBy DOLORES BUTTERFIELD JEFFORDS . . 24Comment from Desert's read ers 26Flowering prediction s for Feb ruary 28Hard Rock Shorty of Dea th Va lley 28Desert Tracks, an d other poem s 29Current ne ws of desert min es 30From here and there on the desert 31For true desert exp erien ces 31Gem s and Minerals 37Am ateu r Gem Cutter, by LELANDE QUICK . . 45Just Between You and Me, by the Editor . . . 46Review s of Southw estern literature 47

The Desert Magazine is published monthly by the Desert Press, Inc., Palm Desert,California. Re-entered as second class ma tter Ju ly 17, 1948, at the postoffice at Pa lm D esert,California, und er th e Act of March 3, 1879. Title reg istere d No. 358865 in U. S. Pa ten t Office,and contents copyrighted 1955 by the Desert Press, Inc. Permission to reproduce contentsmust be secured from the editor in writing.RANDALL HENDERSO N, Edi tor BESS STACY, Business ManagerEVONNE RIDDELL, Circulation ManagerUnsolicited manuscripts and photographs submitted cannot be returned or acknowledgedunless full ret urn postage is enclosed. Desert Magazine assumes no responsibility fordamage or loss of manuscripts or photographs although due care will be exercised. Sub-scribers should send notice of change of address by the first of the month preceding issue.

SUBSCRIPTION RATESOne Year $3.50 Two Years $6.00Canadian Subscriptions 25c Extra, Foreign 50c ExtraSubscriptions to Army Personnel Outside U. S. A. Must Be Mailed in Conformity WithP . O. D. Order No. 19687Address Correspondence to Desert Magazine, Palm Desert, California

F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

4/48

At Travertine Point near the Salton Sea the ancientwaters of Lake Cahuilla encrusted the once submergedrocks with these deposits. In this area the prehistoricshore line is clearly visible for several miles. This inun-dation mav have occurred within the last 1000 years.

Library of the Ages. The lower Grand Canyon o f theColorado 5000 feet of rock strata whose giant pagesof stone lying one upon the other tell a fascinating storyof a changing world. View is from ancient travertinecave across Lake Mead toward E mery Falls.

Tomorrow's Deser t . . .By HULBERT BURROUGHSPhotographs by the author

E WERE industriously engagedone afternoon collecting fossiloyster shells in the Yuha Basinnear El Ce ntro, California. I was con-vinced that we had found the famousold Yuha Reef about which many ageologist had written a remarkablebed of Ostrea Heermani which hadlain practically undisturbed for some17,000,000 years since the living or-ganisms thrived in a once shallow sea.Time and again we picked up fossilspecimens with both halves of the bi-valves still in place.

17,000,000 years! It was difficultto comprehend such staggering lapsesof time, and as we marveled ourthoughts inevitably turned to the spec-ulative. He re was incontrov ertibleevidence that the desert we now knowwas once a very different place. Durin gPliocene timesand probably severaltimes before and since then it hadbeen covered by the sea. We remem -bered, too, the coral reefs not far tothe west in Carrizo Creek . To thenorth in the Borrego Badlands another

We live on an ever-changingearth. Over a period of millionsof years every part of the earth'ssurface has undergone radical al-terationsin temperatures, in rain-fall and in general topography.The deserts will not always re-main as they are now. No humanbeing can foretell just whatchanges will take placebut hereis a summary of what some of thescientists are thinking, in terms ofthe distant future.

fantastic story of the past had beendug from the red and brown claysskeletons of mastodons, camels, anci-ent horses, bisonanimals of a long-dead age that once roamed these plainsand hills. Again the nature of thoseanimals was prima facie evidence thatthe desert then was not what it is to-day. It must have supported a farricher flora to have nourished that vastherbivorous assemblage.

A few miles northeast of BorregoValley lies another silent and remark-able imprint of the changing world ofyesterdayan old shoreline clearly de-

fined along the cliffs high above theprese nt level of the Salton Sea. Soonour memories were groping for othereviden ce of a past far different fromour own familiar desert. Someo ne sug-gested ancient Lake Mo jave. Tha t cer-tainly meant an era when water wasmore plentiful. Wh at of the once greatPyramid Lake in Nevada? And Utah'sfamous Great Salt Lake? That wasonce a very much larger lake than itis today.

What of the very rocks of the desertitself? No m ore vivid story exists inthe world today than the awe-inspiringhistory of the ages written in the giantpages of stone lying one upon the otherin the Grand C anyon. And there aremany o thers like them indispu tablefacts, imprinted upon the ageless rocks,of a changing world that throbbed andteemed with life long before man ap-peared upon the scene.From these thoughts and specula-tions of what the desert had been inpast ages, our minds inevitably turnedto the prospects for the years andcountless ages to com e. W hat of thedesert's future? Wo uld that familiarlandscape remain as it is until the end

D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

5/48

Where hardly a tree stands today, this fallen jorest giant, now petrified, tells of along-gone day when a vastly wetter climate and a more abundant flora existedin Nevada's arid Valley of Fire.of time? Or would it, as it has d onecontinuously in the past, see manymore changes? Some might say thatthe desert has already changed in thepast 20 years. They po int to the effectsof irrigation upon the great ImperialValleynot long ago as much a partof the desert as the sandiest waste.They will point to the All-AmericanCanal and to Hoover Dam and LakeMead. These, they say, are greatchanges for the desert. Gre at changesperhaps for the very isolated locale inwhich they exist, but upon the vastexpanse of the entire desert they arebut drops of a fleeting winter rainswallowed up in the thirsty sands.

Some have gone to considerablelength to expound the theory that LakeMead, 115 miles long and the greatestartificial lake in the world, is boundto alter greatly the climate of the des-ert. Soon, they predict, lush vegeta-tion will spring up because of thehumidifying effect of Lake Mead'sevaporation upon the desert air. I havetalked personally to men of the Na-tional Park Service who are keepingmeteorological records at Lake Mead.Some of their instruments may be seenfloating on a great raft not far fromPierce Ferry . At only a few inchesabove the surface of the lake the hu-midity is practically as nil as it is overthe rest of the bro ad des ert. As oneof the rangers told me"Lake Meadhas about as much effect on the sur-rounding desert climate as a pitcher

of water on the speaker's stand at anational convention."For the future of the desert we mustlook not so much to man-made influ-ences as to great natural forces farbeyond our power to control. We musttake the long-run view. An d in doingthis we must put from our minds thepossibility of any great changes withinour lifetime or the lifetimes of ourchildren's children's children. If anychange is to come it will come slowlyas the result of vast natural forces act-ing over a period of thousands of years,perhaps millions. True, there may beoccasional slight variations in climatewhen the rainfall for a few years willbe either far above normal or far be-lowlike the great drouth in the years1275-1299 A.D. that so affected In-dian life in the American Southwest.But these variations are to be expectedbecause added together they are whatmake, in the long run, for the averageor normal conditions.The great forces of Nature are evennow at work changing our world. Theyare forces that are so infinitesimallyslow in progress that we are scarcelyconscious of their action. Fo r instance,geologists are fairly certain that thePacific Coa st in general is rising. It isalso known that the Atlantic Coast issinking. At certain points in Californiathere are very ancient wave-cut beacheshigh above the present sea level. Th ehills above San Pedro are good ex-amples. Soundings at the mouth of

the Hudson River show the ancientchannel gorge to extend several milesout beyond New York Harbor. Moun-tains are being eroded aw ay. Sea bot-toms are accumulating vast deposits ofsediment. Earth quak es, a more spec-tacular demonstration, are a sign ofthe shifting ever-moving earth-crust.All these processes are relentlessly atworktoday, now.It is difficult, however, adequately tomeasure or evaluate the snail-like prog-ress of all these present vast forces.Perhaps a clearer and more propheticpicture of a possible future is revealedin the fantastic story of the earth'sgreat geological past. It is a story ofvast changes occurring over incon-ceivably long periods of time. Of aonce molten earth gradually cooling;of a surface crust that began to shrinkand caused mountains to rise like thewrinkles on a dried prune. Large areasof land became submerged. Huge de-posits of sediment collected at the bot-toms of the resultant shallow seas.Later those same land areas rose againfrom the sea and with them came thesedimentary deposits that we now rec-ognize in the vast strata of the GrandCanyo n. The re were long eras of localaridity when various parts of our coun-try were desert landswhen wind andocean curre nts must have followed dif-ferent paths from those today. Fa rback in Silurian times New York andOntario were part of a desert. Again,in the Devonian period there was wide

F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

6/48

'" /} ' , ,'( , *

; !< V

7 'T ra p o/ ?/?e ,4 gey. Rubbles of gas still rise from the sticky pools of the LaBrea Asphalt pits as they did 100,000 years ago when many great mammalsof the Pleistocene became mired in their depths.

spread aridity in New York and Penn-sylvania, Qu ebec and Scotlan d. Stilllater, in the Permian Period, Kansas,Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexicowere a desert. In the Connecticut Val-ley there are evidences of desert de-posits over 10 ,000 feet thick. NewJersey has rocks of the same ageTriassic which are thought to beover 20,000 feet in thickness.In addition to these enormous forcesresulting in mountain building, erosion,and land submergence, there wereperiodic ice ages when large areas ofthe earth were covered by huge icesheets many thousands of feet thick.During Permo-Carboniferous times themost extensive glaciation of probablyall time covered tremendous expansesof every continent but Europe andNorth A me rica. Of all period s of gla-ciation, however, the one most affectingus occurred during the Great Ice Ageof the Pleistocene starting about a mil-lion years ago and lastingexcept forthree warmer interglacial periods -until only about 25,000 years agowhen the ice began its final retreat.During this remarkable era the vastice cap in North America covered all

of Canada and extended as far southas Kansas City and St. Lou is. In Eu -rope all of Scandinavia was ice coveredand the white mantle reached downinto North Germany (as of 1938) andWestern Russia. Except for the south-

ern edge of England, the British Isleswere entirely covered.Of important significance was thethickness of this gigantic ice field. TheCanadian pack, which reached downinto the U.S., is estimated to have at-tained a maximum thickness of 10,000feetpractically two miles of solid ice!This meant that an enormous amountof water was taken from the oceans inthe form of water vapor and added tothe ice pack in the form of snow andice. With all this frozen water piledhigh upon the lands the level of theoceans was lowered by some 200 feet.This naturally made dry land bridgesof large areas of shallow seas and en-abled all sorts of land animals to passback and forth from one continent tothe other. The wooly mam moth andhis contemporaries crossed the thendry Bering Sea between Siberia andAlaska. England was part of the con-tinent of Europe.Climatic conditions must have beensevere in our coun try. Th e High Si-erra for instance were crowned withlarge glaciers. Yosemite received itsartistic sculpturing by glaciers duringthe Pleistocen e. Ou r great Southwestsaw none of the aridity it knows today.Utah's Great Salt Lake is only theshriveled remnant of huge Lake Bon-neville which during the Great Tee Agewas nearly ten times its present size.The old shoreline of that lake is stillvisible a thousand feet higher up the

mountains. There were no deserts inthe United States in those years andgreat mammals roamed throughout theland south of the ice packs.Remembering that these were allnatural phenomena that took place inthe past, we justifiably wonder whatthe prospects are of any of them re-curring in the future. Wha t causedthe Great Ice Age? Are those samecauses likely to occu r again? No oneknows for sure what caused the iceages of the past. Th ere are manytheories and here are some of them:Some scientists attribute the markedclimatic change to variations of direc-tion in the polar axis of the earth.There are said to be definite indicationsthat the earth's poles are slowly shift-ing even now. Some claim that o ursun is a variable star and is subject tomarked changes in the amount ofheat it gives out. Sunspo t activity weknow influences our climate to a cer-tain extenthow we do not yet know.Other scientists point to changes inocean and wind currents, even to avariation of the temperature of spacethrough which our earth is travelling.Some say that ice ages result whenplant growths use up a substantialamount of the carbon dioxide in theatmosphere.One interesting theory to explain thefall in temperature that caused an iceage holds that the marked activity ofexplosive volcanoes during the Pleisto-

D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

7/48

cene filled the upper atmosphere withgreat clouds of fine volcanic dust whicheffectively blanketed the earth fromits normal quota of the sun's heat.Partially supporting this theory is theacknowledged fact that there was ex-tensive vulcanism during the Pleisto-cene. The terrific Krakatoa eruptionof 1883 gives us a fair idea of whatmay have happened on a large scaleduring the Pleistocene. When thisfamous volcano blew its top in whatwas probably the greatest explosion inthe history of man, volcanic dust shotinto the upper atmosphere and waseventually scattered over the entireglobe. The sound was heard more than200 0 miles away. Fo r three years af-terwards the dust in the upper atmos-phere caused strange and beautifulsunsets. An atmospheric pressure wavecircled the earth three and a half times.A fifty foot tidal wave killed more than30,000 people and wiped out countlessvillages.

The assumption of those who sup-port this theory is that if one volcanocould do all this, many volcanoes act-ing during the Pleistocene may havesent forth enough dust to have effec-tively screened out much of the sun'sheat.Whatever the cause or causes of anice age, our logical question is: Arethey likely to occur again in the future?Scientists do not venture too far along

the roads of proph ecy. Yet considerthis: During the Pleistocene therewere four separate glacial periods in-terspersed by three very long inter-glacial or warmer periods during whichtime the ice greatly receded. We areonly now in the process of thawing outof the last glacial period. Th e icestarted to recede about 25,000 yearsago. The 5,000,000 cubic miles of icestill piled up in Greenland and Antarc-tica indicate that we are not yet com-pletely out of the ice age. fs it notpossible then that after a long periodof warmer climate another ice age willcome? Some scientists think so.Sir James Jeans, eminent Britishscientist, offers several other interest-ing prosp ects for the future. Th e sun'sloss of weight due to dissipation of itsenergy, says Jeans, is allowing theearth to recede away from it at therate of about three feet a century. Thusafter a mere million million years theearth will be ten percent farther awayfrom its source of heat and light. Thiswill mean a 30 degree Centigrade dropin the earth 's surface temp eratu re. Allof our oceans, lakes and rivers willfreeze solidthe earth a vast frozendesert. Life, thinks Jeans, would prob-ably be able to survive this ordeal butit would not be easy.Jeans says there are accidents, how-ever, that might occur to the earth in

far less time than a million millionyears. Our sun might suddenly shrinkto a dwarf stara phenomenon whichastronomers have seen happen manytimes to other suns. This abru pt les-sening of heat and light would seal thedoom of all life on earth . Ocean swould freeze and the atmosphere wouldbecome liquid air.Another of Sir Jeans' optimisticpossibilities is that our sun will sud-denly flare up into a nova. As tron o-mers have seen these novae blossomquite often. They are ordinary starswhich for no apparent reason suddenlyflare up into tremendous intensity,burn brightly for a short time and theneither fade away completely or returnto their norma l state. This is all veryinnocent except that in the process alllife would be scorched from the faceof the earth . Every star in our galac-tic system, thinks Jeans, is subject tobecoming a playful nova at least onceevery 50,000 million years. The ques-tion we are interested in is: Does o ursun face the danger of becoming anova? Jean s thinks so thin ks thechances are that it will become a novaat least twenty times during the nextmillion million years. I offer the hum-ble suggestion, though, that in antici-pating this cataclysmic but uncertainevent there is little need to alter ourplans for next week-end.

To return to subjects more withinour grasp, geology tells us that by far

the longest periods of time have seenthe earth basking in a warm and humidclimate in which plant and animal lifeflourished from pole to pole. Th atcondition is the normal over millionsof years of the geological history ofthe earthno extreme cold, plenty ofrain, perfect environment for thegrowth and progress of life. The coldglacial periods, coming in irregularcycles, are the abnorm al. Over longperiods of time climate has swung pen-dulum-like from hot to cold. Everyknown geologic age shows signs ofthese alternating periods from normalto ice age. Altho ugh long in relationto man's reckoning of time, these coldspells are quite short in the history ofan era.

Whatever the primary cause of gla-ciation it is a period of fairly suddenand profound change in which life issubjected to the most rigorous of tests.Only the hardiest and most adaptablecan survive. Of the great Pleistocenemammal assemblage practically allhave died off. Th e elep han ts, rhino c-eroses, hippopotamuses, etc., of Africaand India are but a few scattered rem-nants. M an and his faithful satellitethe dog seem to have been the mostadaptable to the rigors of a changingworld.Because we arc only just emergingfrom the last ice age our climate is stillcolder than normal. If we are enteringone of the warm intcrglacial periods

The great American Lion (Felis atro.x Leidy) was nearly a third larger thantoday's African counterpart. Why did this magnificent King of Beastsbecome extinct? What changes in southwest climate wiped him from the faceof the Earth? Are those same changes and their motivating forces stillgoing on today?

F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

8/48

T h e H m m i n g b i t d C a f e t e r i aYEARS AGO, after a dry fall and winter and an almost rain-less spring, Laura Riffey appointed herself a one-woman disastercorps for the birds and wildlife which visited the isolated Riffey

ranch near Fred onia, Arizona. She scattered grain night and morning forGambel quail, white-crowned sparrows and house finches, and water wasalways available for all wild visitors.The second week of March, the black-chinned hummingbirds re-turned for their nesting season. It wasn't a very happy homecom ingthere were no flowers and only occasional insects.Providing emergency rations for the hungry hummingbirds proved aperplexing problem.First Mrs. Riffey rigged small evaporated milk cans, lids half open,with colored bits of cloth, filled them with a weak honey-water solutionand hung the improvised feeders in junipers and pinyons surroundingthe house.But, although they investigated thoroughly, the hummingbirds justdidn't get the idea. The honey water was untouched, and the birds con-tinued m ealless.A better advertising campaign was indicated, the Riffeys decided.A storage trunk yielded colorful artificial flowers, the medicine chest somesmall bottles. Alon g the wide window sills of the house, the bottles, brig htpaper flower pulled over each small neck, were "planted" in pebble-filledflower pots. Tipped at a slight angle, the glass vials allowed easy accessto the sugar liquid within.The row of rainbow-painted pots with their curious plantings at-tracted hummingbirds immediately, and within a few minutes the "Hum-mingbird Ca feteria" was doing a thriving business. Eac h year since, thebirds have returned to renew their patronage during nesting time.The Riffeys derive hours of enjoyment watching their tiny customers.At first they observe the courtship dives and swoops and the rivalries for

feeding vials. The n the young are born, and the paren t birds begin thecountless trips between window sill and nest, bringing sweet nourishmentto their babies. It is not long before the little ones acco mpan y M om andPop to the cafeteria, to perch on the flowers and dip long beaks into thesweet liquid within. La ter, like their pare nts, they drink from mid-a ir.The honey water attracted flies, moths and insects as well as birds,the Riffeys soon discovered. Eve ry mornin g they ha d to fish out deadinsects with a long nail. Th en suddenly the bug problem was solved. AScott's oriole which had watched the hummers at the cafeteria one morningdecided to investigate the flowers himself. He discovered the combinationand had a good sweetmeat breakfast. Soon he was bringing his wife toenjoy the sugar-preserved insects and, later, his young.The bottles are kept filled with a light solution of honey or sugar andwaterabout Wi tablespo ons of sweet per cup of wate r. To o heavy asugar concentration would present a sticky problem to birds preening theirfeathers after dining. Th e artificial flowers wore out tha t first season, andsince then small pieces of bright colored oilcloth have been substituted,cut in petal-like shapes and pulled over the bottle necks. The Riffeys havenoticed no color preference.

we may look to a more equable worldclimate in the centuries to come. Ifs o , what will that mean for our des-erts? More heat may mean more deso-lation a broadening of the desertwastes unless the changing climatebrings with it more rain.The late Professor Percival Lowell,famous for his study of the planetMars , intimates that the earth is fol-lowing along the evolutionary path ofthat dying world. He claims that oursister planet is much older and thatits atmosphere is slowly dissipating, itswater supply drying up, its surfaceeroded down to a nearly level plain.In short, it is a dying world fast be-coming a desert waste. He predictsthat will be our fate at some time inthe far distant futureour world avast waterless desert.John Van Dyke, in his little bookThe Desert, says: ". . . Have we notproof in our own moon that worldsdo die? . . . And how came it to die?What was the element that failed -fire, water, or atmosphere? Perhapsit was water. Per hap s it died throughthousands of years with the slow evap-oration of moisture and the slow growthof the dese rt. Is then this great ex-panse of sand and rock the beginningof the end? Is that the way our globeshall perish?"Yet as we have seen earlier, therehave been in past geological ages fargreater deserts than exist todayandin areas that are now lush with vege-tation. New York, New Jersey, Co n-necticut, Pennsylvania, Kansas allwere deserts at one time or anotherin the pas t. We have seen that our ownSouthwest once supported a formidablearray of animals ranging from camelsto mastod ons. We know that theseanimals no longer exist there. We knowthat the sea came and receded severaltimes in the pas t. The re is thus noindisputable evidence of a definitetrend for the future.All we can truthfully say of thedesert's future and the future of ourworld is that it is a dynamic ever-changing world. Wh at the ages to comewill hold, no living man can know.But of this at least we can be cer-tain, it is a world charged with tre-mendous forces that are even nowshaping the course of things to come.It is a world rich with infinite possi-bilities for man . W ould tha t we oftoday might be here to see it unfold!BIBLIOGRAPHY:Outlines of Historical Geology Schuchertand DunbarIce Ages Recent and AncientA. P. Cole-manThe Earth and Its RhythmsCharles Schu-chert and Clara M. LeVeneThe Universe Around UsSir James JeansThe Cause of an Ice AgeSir Robt. BallMars as the Abode of LifePercival LowellThe DesertJohn Van Dyke

D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

9/48

. . - . v^-' .:v.y

It is estimated there are 2500 native palms along Palomar Canyonbelow the hot mineral spring described in this story.C a t t l e R a n c hAmong the PalmsBy RANDALL HENDERSONMap by Norton Allen

/]N FEBRUARY, 1947, following/ an exploring trip into Baja Cali-fornia, I wrote a story for DesertMagazine titled "Palms of Palomar."It was a beautiful canyon of nativepalm trees 80 miles south of Mexicalion the desert side of the Sierra Juarez,that mountain backbone which sepa-rates the coastal from the desert por-tions of the Lower California peninsula.

I thought it was a very good storybut recently I learned that I hadmade a serious error. I gave the can-yon the wrong nam e. The story shouldhave been titled "Palms of Santa Isa-bel." For actually I was in Santa Isa-bel Canyon, three miles south of Palo-mar.

There are no official maps showingall the topographic features of BajaCalifornia. When Aries Adam s andBill Sherrill and I go down there tohike into the canyons which border theLaguna Salada dry lake, we dependon the word of the Indians and Mexi-can vaqueros for our place name in-formation. Somehow, we got crossedup on Palomar.Recently, Aries Adams called myattention to the error. "Wh en youhave the time, we'll make another tripdown there and get those place namesuntang led," he wrote me. "I 've beentalking with some of the Mexicans whorun cattle in those desert canyons, and

while there is a Palomar Canyon, it isnot the one we thought it was. Thecanyon you wrote about was SantaIsabel, and Palomar is the next maincanyon north of it."We arranged the trip for the week-end of M arch 13-14 last year. Inaddition to Aries and Bill, our two-jeep party included Jimmy Marshall,seed dealer, H. K. McCracken, schoolteacher, and Sterling Cowman, Jr.,student, all of El Centro, California.From the Mexicali port of entry wemotored west on the recently pavedhighway that connects with Tijuanaon the coast. Seventeen miles fromour starting point, at the base of Mt.

Signal, we left the pavement andturned south across the great smooth-surfaced playa marked on old mapsas Laguna de Maquata, and more re-cently as Laguna Salada. This inlandsea once had a greater surface areathan Salton Sea, but was never asdeep as Salton.We were following a road used byMexican woodcutters who make ameager living by bringing in ironwood.mesquite and palo verde for the fireplaces of Me xicali. La ter we passedone of the wood crews cutting fire-wood in an arroyo . It requires twodays for three men to cut and delivera load of wood in Mexicali. Fo r theload they receive 220 pesos, which atthe present rate of exchange is theequivalent of $17.60.

Petroglyphs were found on theserocks near the canyon entrance.Continuing his exploration of themany desert palm canyons southof the border in Baja California,Randall Henderson this monthwrites cf a remote catt le ranchwhere the mountain l ions ar e soplentiful, armed cowmen have toguard their calves at night.

We left the dry lakebed at PozoCenizo where a cattle outfit once hadits headq uarters. The old cementwatering troughs are still there, and20 feet down in an open well israther brackish waterbut there is noway to get it out unless one carrieshis own rope and bucket.From that point we followed awinding trail which leads eventuallyto the Pai-Pai Indian camp in ArroyoAgua Caliente (Desert Magazine, July' 5 1 ) . At 171/2 miles from Pozo Ce-nizo a little-traveled trail leads offtoward the rugged Sierra Juarez onthe west, and this was the road whichafter 10Vi more miles of sandy androcky travel brought us to the end ofour trail at the edge of Palomar Can-yon.Where our road ended we couldlook down on hundreds of native palmtrees, extended along the bottom ofthe arroyo as far as we could see inboth directions.Actually we had passed near themouth of the canyon some distanceback, and for seven miles had beentraveling across a mesa on a road thatran parallel to Palom ar. We hadstopped briefly and hiked to the can-yon's entrance to hunt for some Indianpetroglyphs we had been told were onthe rocks there. We found glyphs, andalso palms, although there was nosurface water at that point.We gathered firewood and made

F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

10/48

camp beside the arroyoin a naturalgarden of Sonoran desert vegetationironwood, palo verde, ocotillo, cats-claw, staghorn and bisnaga cactus, allplants found on the American side ofthe line. But there were two strangersheresenita or old man cactus, andelephant tree.With camp established, we hiked ahalf mile upstream along the rockyfloor of Palomar to the cow camp ofTomas Dowling, who has grazed cat-tle in this canyon for many years.Tom lives in a tent-like shelter madeof palm fronds, his only companionbeing 78-year-old Manuel Leon, agambucino (prospector) who hasturned cowhand.Until a year ago they had comfort-able quarters in an ancient adobe

house near the little cluster of palmswhere their camp is located. But a73-year-old cowhand died in theadobe, and like the Navajo Indians,Tomas and Manuel are a bit super-stitious about such things, and nowthey sleep under the palm fronds andcook in the shade of a group of tallWashington palms.They had been having trouble withmountain lions. To protect their chick-ens and pigs they have built stockadesof palm trunks, and at night they roundup the calves and keep watch overthem with a gun.Palomar Canyon has had no rainfor many months and the forage issparse. We saw evidence of this whenwe came upon some of the youngsteers eating palm fronds, chuparosa

and staghorn cactus. Livestock resortto such food only when no other vege-tation is available.Dowling told us that in a few dayshe would drive the herd up the 4000-foot trail to the top of the mountainsnear Laguna Hansen for summer for-age. But while the cattle were on shortration s, the pigs were fat. They eatroots and herbs, and when the datesare in fruit they feast on the sweet-skinned seeds.My estimate is that there are over2500 native palms along PalomarCanyon, about 10 percent of them theblue palm, Erythea armata, and theremainder Washingtonia filifera. Theblue palms carried great clusters ofgreen fruit, about the size of smallmarbles, when we were there.Dowling has a well among the palm

trees, and is trying to develop waterto irrigate a little field of forage forhis livestock. He was wrestling witha balky gas engine when we arrivedat his camp . Aries, who is a geniuswith mechanical gadgets, took overthe job and soon had the pump throw-ing a big stream of water.With the exception of the gas en-gine and a truck for occasional tripsto Mexicali, 74 miles away, for sup-plies, Dowling and Leon have onlythe most primitive tools for their cattlebusiness. After the pump was started,Tomas walked to a nearby tree andbegan braiding a cowhide lariat withbobbins of thong he had cut and curedhimself.Manuel told us about a hot springwhich bubbled out of the groundamong the palm trees three miles upthe canyon, and the next morning heguided us up there. The spring gushed130-degree water out of a grassy parkfringed with palms. If such a springhad been in the Santa Rosa or Cata-lina or Wasatch mountains, some onewould have built a million dollar sani-tarium around it long ago. We knewby the fumes it was mineral water, andno doubt it had medicinal value knownto the Indians of long ago, for therewere many grinding holes and metatesin the boulders in that vicinity.

The palms in the canyon had allbeen burned at a recent date, andManuel told us it was done by a Mexi-can boy who stayed at the camp sixyears ago. Apparently all the treeshad survived the fire, and had startedacquiring new skirts of dead fronds.Following down the stream to thecow camp later, I discovered thatDowling had built an earthen dam anda two-mile ditch in an effort to bringirrigation water to his cabinsite for agarden. But with only hand tools forthe construction it is very crude, and10 D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

11/48

A spring of 130-degree water gushesout of the ground in a natural parksurrounded by palms.the ditch delivers water only when themain stream is at a high level. It wasbecause of the unreliability of thiswater supply that Dowling bought thegas engine which he was trying to startwhen we arrived in his camp.

Tom Dowling definitely confirmedthe information that this was PalomarCanyon, and that the next canyon tothe south, which 1 previously had

With a stream fed by the hot min-eral spring, Palomar Canyon is aseries of lovely vistas.mapped as Palomar actually is SantaIsabel Canyon.Both of them have live streams ofwater, and forests of palm trees. La-guna Hansen, on the plateau above isbut 14 miles from Dowling's camp.Manuel told us of another canyon justa few miles to the north which alsohas many palmsAiamar Canyon, henamed it.With more and more desert motor-ists acquiring 4-wheel drive cars, there

Tom Dowling supplies his cowhandswith rawhide riatas which he braidsin his spare time.is increasing travel to the many lovelypalm canyons which gash the desertslope of the Sierra Jua rez ran ge. Noofficial maps arc available showing allof these canyons, but as a result ofmany scores of exploring trips intothat remote region, the map accom-panying this story is offered as themost complete record yet compiledof this fascinating portion of BajaCalifornia.

The old adobe ranch house was abandoned after one ofthe cowhands died in it a few months ago. Manu el Leon beside the palm-front lent which nowserves as home for him and Tom Dowling.

F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5. . .m

i i

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

12/48

ON DESERT TRAILS WITH A NA TU RA LIST - XI

Turkey Buzzards day-roosting on saguaro, Sonoran Desert, Mexico.

Scavengers o f SonoraBy EDMUND C. JAEGER, D.Sc.Curator of PlantsRivers ide Munic ipa l Museum

Photo and ske tch by the authorD YOU EVER see so manyhawks, or are they youngeagles, all sitting together?"exclaimed my traveling companion,Bill Wells of Riverside, California, aswe sped northward along a road of thedry Sonoran Desert of Mexico's westcoast. "W hy, there's six of them sit-ting on the branches of one organ-pipecactus! Never before have I seenhawks doing that ."

"Those aren' t hawks," I said, "al-though they may look like them toyou. Those are extraordinarily cleverbut odd looking birds called caracaras,near relatives of hawks but moreclosely related to falcons. Som etimesin the United States they are errone-ously called Mexican buzzards orMexican eagles; buzzards because oftheir carrion feeding habits, eagles,because of their appearance in flight.O ne of the birds was standing onthe ground, and as the car came nearer,we could note the birds' distinctivecolor markings black head-crown,whitish neck and breast, black to dark

One of the most c o m m o namong birds seen by the trav-eler in Sonora is the Caracaraa distant relative of the NorthAmerican Turkey Buzzard. Ina land where there are fewgarbage collectors, these car-rion birds serve a useful pur-pose and are protected byunwritten law . Naturalist Ed-mund Jaeger introduces anotherstrange denizen of the desert.brown back and belly and white dark-tipped tail. As we drew still nearerwe could see the eagle-like beak andred face. They seemed quite undis-turbed by our presence until we gotout of the auto; then one after an-other they took wing, their long un-feathered legs extending downward atan angle of about 45 degrees from thehorizon tal. We noted, too, their pe -culiarly outstretched necks and thepale patches of color at their wing tips.As we traveled northward the birdsbecame more and more common untilwe were counting 12 to 15 to the mile.All were readily seen silhouettedagainst the sky, perched atop roadsideorgan-pipe or giant cacti. Occasionallywe saw one perched bolt upright on

. .the topmost branches of an ironwoodtree.1 would say that caracaras are thesecond most frequently seen of thelarger birds of the region, the firstbeing the almost eagle sized zapalotesor turkey buzzards. Caracaras areprimarily carrion eaters, but also killmany small animalsskunks, rabbits,mice, fish, small birds and morehumble quarry such as beetles, cicadasand grassho ppers. Their long stronglegs make them rapid runners and onesometimes sees them running downtheir prey. The birds frequent high-ways where they find wounded or deadanimals which have been run down,especially at night, by speeding auto-mobiles.

Their aggressiveness when in pursuitof food makes them the respected foeof even larger birds. I once had the ex-citing experience of seeing a Red-tailedHawk swoop down and grasp a four-foot gop her snake in its talons . Nosooner had it taken wing than threecaracaras boldly gave chase, attackingthe hawk in mid-air by plunging downupon it from abov e. This they keptup for some minutes until they forcedthe hawk to relinquish hold upon itsreptile prize. As the snake drop ped12 D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

13/48

all three carac aras dash ed for it. Anaerial quarrel followed as each for amoment grasped the snake only tosurre nde r it to ano ther. Finally oneof the caracaras, bolder and moreadept in flight than the others, gothold of the squirming reptile and madeoff with it.This bird of the open country is anunusually quiet one, but if it is woundedor excited it stretches its neck, throwsits head back until the black crownalmost rests on the shoulders and givesa strange and prolonged raucous cry.This same peculiar call, somewhatvaried, may sometimes be heard earlyin the morning or just after sundown.The name caracara, given by Braziliansto one of its near relations, is supposedto be an imitation of this loud harshcall.Caracaras are said to mate for life.Families often live and hunt togetheruntil the young reach near-adulthood.Each pair has its separate nesting androosting place; these they occupy yearafter year. All the nests I have seenhave been built in large mesquite orironwood trees. They were large bulkystructures with a slight central depres-sion, made of small tree branches andlined with sticks, grass and roots.The caracara of the west coast des-ert of Mexico is Audubon's caracara,Polyborus cheriway auduboni. It oc-casionally comes into our deserts ofsouthern Arizona, southwestern NewMexico and Texas along the Mexicanborder. Strangely enough, this unusuallooking desert bird is found also inparts of Florida, Cuba, Guiana andEcuador in an environment as undes-ert-like as one could imagine.The carancha, so well and delight-fully described by W. H. Hudson inhis Birds of LaPlata is another speciesof caracara, Polyborus tharus, livingon the vast grassy plains of Argentina.Formerly another species, Polyboruslutosus, inhabited Guadalupe Island,175 miles off the west coast of LowerCalifornia. Its disap peara nce is atragic story that illustrates the follyand damage which may be done whenman interferes with the native faunaand flora by over-hunting and the in-troduction of domestic animals.When Dr. Edward Palmer visitedGuadalupe Island in 1875, the que-lelis, as the natives called the bird, wasto be seen in great numbers in spite ofa continual persecution waged againstit with poison and guns.Because of man's persecution, notonly has Guadalupe's caracara disap-peared, but due to his introduction offoreign animals the native vegetationof the once beautiful island has suf-fered immeasurably. Ma n brought inwith him not only his goats but alsocats. On boa ts visiting the island camethe domestic mou se. The mice con-

Caraca ras are easily recognized by their distinctive markings black headcrown, whitish neck and breast, black body and white-tipped tail. Itsraucous call is given with head thrown far back.sumed the seeds of many native plantsbringing them almost if not completelyto the point of extinction . Th e catsincreased and, since they were alwayshungry and crafty hunters, they helpedin the extermination of the small birds.The goats, ranging far and wide, allbut destroyed the native shrubs andtrees. Only on a few fog-drenched,isolated cliffs does the magnificentGuadalupe cypress yet maintain astand.The great food competitor of theMexican caracaras are the zapolotesor turkey buzzards. However they sel-dom if ever feed at the same "table,"although both are attracted by thesame carrion.The Turkey Buzzards are protectedin Mexico by a kind of unwritten law.The people seem to realize that theyare valuable scavengers and that in noway do they conflict with man's inter-ests; therefore, seldom do they molestthem. Under these conditions the birdsbecome very tam e. One sees themeverywhere sitting in groups on theground, roosting in trees, or circling

overhead, especially along the roadsidesand about the borders of country vil-lages where the native people dependon them for the disposal of dead ani-mals, from dogs to donkeys.I have seen as many as 20 buzzardsfeeding wholly undisturbed on a burrocarcass within a stone's throw of avillage entr anc e. On e frequently seessmall flocks of them partaking in anequally ignoble feast on the roadside.It is quite common to see a greatflock of these birds circling over atown. In fact, one can often d etectthe probable site of a village long be-fore one approaches it just by the sightof the circling buzzards.Last autumn I witnessed the unus-ual sight of at least a thousand ofthese birds bathing and resting at mid-day along the Maya River near Nava-joa. The sandy river bottom was lit-erally black with them as they sat inclose formation silently sunning them-selves after bathing in the broad shal-low stream. Man y had wings widelyoutspread the better to catch the fullbenefit of the sun's rays.

F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5 13

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

14/48

Desert Peakers named this peak "Whipple I" a f t e r spotting from its to p a highersummit still in the California range. The hikers missed a second t im e b e f o r evictory on Whipple III.Three Tries to the Topof the Whipple Range

One hundred years to the day after Lieutenant A. W. Whipplecamped beside the California range which today bears his name,m e m b e r s of the Sierra Club hiked to the mounta ins' highest p eak . Twofalse summits were reached before they finally stood on top. Here isthe story of a persevering group of mountaineers and the army officerwho played an important role in the scientific delineation and recordingof the geog rap hy of the W est.

By LOUISE T. WERNERPhotos by Richard L. KenyonMap by Norton Allen^ y y A S H I N G T O N S BIRTHDAYffl/ dawned chilly but clear atChambers Well in the south-west foothills of California's WhippleM ountains. It wasn 't a pretentious

campground, only a wash where halfa dozen cars of Sierra Club moun-taineers had stopped the night before.Our weekend goal was the highestpoint in the Whipples, a small desertrange 4131 feet above sea level lying

in a crook of the Colorado River 35miles south of Needles, California.Sleeping bags hugged the sandy des-ert floor like so many brown cocoons,stirring to life as their occupants tum-bled out. Fires flared in the half-lightas boiling coffee, bacon, corned beefhash, frying eggs and palo verde smokeperfumed the crisp cool air.It wasn't easy crawling out of downbags into the cold. But once bundled

in shirts, sweaters and parkas, huddledclose to small cooking fires and sippinghot coffee, everyone soon was awakeand cheerful.As I packed a noon lunch into aplastic bag, a small figure came scram-bling over the rocks, a miniature moun-taineer, complete with hooded parka,mittens and knapsac k. "My name isBetsy Bear," she volunteered. "What'syours? " She was four, she said, a ndwas "a Desert Peaker just like Mommyand Dad," Bob and Emily Bear.Light was beginning to silver thespines of giant cholla cactus on thewest bank of the wash when LeaderJohn Delmonte called: "starting in 10minutes!" Right on schedule, 6:30a.m., he started up a draw with 23hikers in tow.Assistant Leader Barbara Lilley fellin at line's enda hard assignment for

14 D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

15/48

a girl who usually leads the pac k. OnFriday evening Barbara had picked upNed Smith, Bryce Miller and MonteGriffin in San Diego, driven most ofthe night, climbed all day Saturday inthe Turtle Mountains, joined us Sat-urday evening at Chamber's Well forthe Sunday climb in the Whipples andplanned to drive home Sunday nightand be back at her office desk Mondaymorning! "I 'm m ore alert on the job ,"claims Ba rbara , ' 'after a strenuo usweekend outdoors."Judith and Jocelyn Delmonte, 9 and11 , scrambled up the rocks right ontheir father's heels. Behind themstrung Bernice and Walt Heninger, twomiddle-agers who can still outclimbmany youngsters, Dick Kenyon, pho-tographer and U.C.L.A. student, JackHudson, a Los Angeles fireman, Wil-lard Dean, vice-chairman of the Desert

Peaks Section, and others.We found n o trails. It was evidentthat miners had scratched here andthere for gold and copper, and it wasprobably they who had dug ChambersWell, a hole in the ground with mois-ture showing. Acco rding to a U. S.Water Supply Bulletin, the well wasfouled by dead animals and abandoned.We found no other water on our climb.In spite of our grumblings at get-ting out of bed, early morning on thedesert repaid us. We soon were warmedby the scramble up the draw, and the

fresh air was exhila rating. No colorfulsunrise this morning; it was too clear.The sun splashed over the ridge,glancing off yellow palo verde barkand the red metamorphic rocks on theslope.Over the next rise we crossed aclean-swept plateau hard with tiny vol-canic mosaic, then over several more,separated by gentle rises, and up a slopedense with man-sized cholla. We allwere familiar with this cactus porcu-pine and advanced warily, trying toavoid the ferocious spines. We had

met cholla often on desert hikes butnever in such sizes or numbe rs. Noneof us escaped unscathed. Jean s, socksand boot-leather were penetrated. WaltHeninger produced tweezers andpromptly became the most popularman in the party.On a volcanic outcropping we pausedto dig out the needles and to appreciatethe breeze that fanned the ridge. Oureyes followed the thread of the Colo-rad o River below. C ut off on the eastby the soaring ridge, it curved aroundthe north side of the range, then around

the south. High in the blue a jetwhined, pouring out a vapor trail. Twoagave stalks, leaning out from the slope,framed what Jack Hudson decidedfrom his topo map was Parker, Ari-zona.

Young Desert Peaker Betsy Bear, 4, daughter of Bob and Emily Bear,warms herself over a breakfast fire before starting on the morning's trek.We climbed and climbedmiles ofridge walking, constantly peering upthe soaring line in the hope of catch-ing sight of a summ it. "Is it the top,Daddy?" Jocelyn would call each timeher father topped a hill. After fourhours of climbing, we all waited anxi-ously for each answer and shared thedisappointment when it came.Suddenly, half a mile away, an ap-preciably higher point arose across a150-foot dip."That may be it," said John."Or maybe just the point from whichyou can see the point from which youview the summit," qualified pessimisticWalt.Two climbers decided to stay be-

hind while the rest of us scrambleddown over the smooth reddish bould-ers and up again. On our left thethread of the Colorado suddenly bulgedinto Lake Havasu, above Parker Dam.Desert peaks usually overlook chalkydry lakes. One of sparkling blue wasa novelty."If this isn't the top," puffed aclimber, "I 'm not going any farther."It wasn 't. Again the ridge dipped,swung right and continued to a pointhigher still."We'll leave everything here exceptcameras and make a dash for it," saidJoh n, eyeing the sun. It was alreadyan hour past noon . "I 'm afraid th at'sas far as we can explore today."

F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5 15

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

16/48

Th e c l i m b i n g D e l m o n t e family onWhippie II James, 15,Judith, 9,J ocel yn , 11, and Father John Delmonte, leader.Eight climbers decided to stay onwhat we named "Whipple II." Theother 14 followed John over great slabs

of redrock that had weathered out ofthe ridge. We swung tothe right, pull-ing slowly up the long steep incline.John's arm swept the air in victory ashe topped thepoint.

From "Whipple 111,"4131 feetabove sea level and thesummit at last,the terrain fell away in all directions.Lower ridges to theeast still blockedou t a part of the river's loop aroundthe range. Arizona ranges undulateddark brown as far as the eye couldtravel.

We stood onthe top of the WhippleMountains onFebruary 22, 1953. Ex-actly 100 years before, LieutenantAmiel Weeks Whipple was campedwith hisparty of engineers, topogra-phers, geologists, astronomers, botan-ists, artists, soldiers andIndian guidesin theChemehuevi Valley at the footof the Whipple R ange. They were sur-veying for arailroad which was roughlyto follow the35th parallel from FortSmith, Missouri, to thePacific Ocean.The valley which we viewed fromour pinnacle perch was far from deso-late when Whipple was there.

"The beautiful valley of the Cheme-hucvis Indians isabout five miles broadand eight or ten miles in length," hereported in his journal, published in1941 asAPathfinder inthe Southwest."A s weascended theeastern edge,wesaw numerous villages and a belt ofcultivated fields upon the oppositebank. Great numb ers of the nativesswam theriver andbrought loads ofgrain and vegetables. . . . After travel-ing between 11 and 12miles, we en-camped upon thecoarse butabundantgrass of thevalley." This was Whip-pie's Camp 130, February 23,1853.

One of themembers of Whipple'sparty was young Lieutenant Joseph C.Ives. A fewyears later, Ivescom-manded an army expedition ofhis own,exploring the Colorado River in theclumsy steamer, theExplorer. It washe who named TheMonument, mostprominent peak in theWhipple range."A slender andperfectly symmetricalspire that furnishes astriking landmark.as it can be seen from a greatwaydown the river in beautiful reliefTO NEEDLES

'^TURTLE.,.:: M TNS

DiSERT CENTER BO USE

16 DESERT MAGAZINE

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

17/48

I*

Final victory on the summit of Whipple 111, highest point in the Whipple range. Leftto right, standing Barbara Lilley, Louise Werner, Ned Smith, John Delmonte, Gar-ver Light, Willard Dean, Monte Griffin, Jack Hu dson, Bryce Miller, James Del-monte, Walt Heninger, Marvin Stevens; seated Mary Crothers, Bernice Heninger.against the sky," he described it in hisReport Upon the Colorado River ofthe West.The peak so impressed lves that hecalled the entire range the MonumentMountains. Another of the peaks hecalled Mount Whipple after his formercommander. When the GeologicalSurvey mapped the Parker Quadranglein 1902-03, it applied Whipple's nameto the entire mountain mass in thebend of the Colorado, preserving theold name in Monument Peak.We would have liked to linger longeron the top of the Whipples. Thewarmth of the sun bathed our pleas-antly aching muscles as we lunchedand enjoyed the view. "I ain't mad atnobody," remarked Walt .Reluctantly we started down. Pick-ing up our companions on WhipplesII and I, we jogged down a draw southof the ridge we had ascended.Suddenly a dry falls stopped ourrapid progress. Its granite trough,water polished in some past age, was

marble smooth. The rock climbingenthusiasts enjoyed hugging the slip-pery wall, groping for foot- and hand-holds. Others found it disconcertingto trust their weight on a tiny knob ofstone or a precariously slanting slabon the sheer rock face. With team -work, all soon were safely down.

Several dry falls later, we found our-selves in a deep, narrow canyo n. De -ciding we were a little off course, Johnheaded toward a saddle to our right.On its other side, an army of chollalay in am bus h. Sparring with chollain the fresh of the morning was onething; attacking it after a long day ofclimbing was quite another.But just over the next swell wedropped down into camp at ChambersWell. Mrs. Delmonte had water boil-ing and invited us to tea. It wasn 'tlong before dinner fires were blazingand plates heaped with food. Oh, theambrosial flavor of beans, frankfurters,canned peaches and billy-boiled coffeeafter 12 hours on the trail!

INTERNATIONAL BIG BENDP A R K I N P L A N N I N G S T A G E

First steps toward expanding BigBend National Park into an interna-tional park spanning the Rio Grandewere made at informal meetings be-tween Mexican and U. S. officials inMexico City. The proposed park hasbeen in the planning stage since 1935.It would join Big Bend's 700,000 acresto 500,00 0 acres in Mex ico. It wouldbe free of all customs and immigrationred tape, and tourists could cross fromTexas into Mexico without even tour-ist cards. Texas prop onents of theidea believe the addition of spectacularMexican scenery would draw more BigBend visitors. And Mexican officialshope that tourists would continue intothe Mexican interior. L on Garrison ,superintendent of Big Bend NationalPark, expressed optimism that the cur-rent talks would be successful. He wasto step up Janua ry 1 in the NationalPark Service through a transfer toWashington. Los Angeles Times.F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5 17

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

18/48

A gate H u nters in the A pachesAgate is where you find itandhere is the story of the discoveryof a rich new field in the Apache

Mountain country of western NewMexico.By GILBERT L. EGGERTMap by Norton Allen

WAS RE TU RN ING f rom huntingagate in Wilson Canyon when 1found the lost calf. The littlefellow was weak and obviously aban-doned by its mother.Up to this time the mineral hunthad gone from worse to terrible.Where I had hoped to find chalcedonyroses, there were slabs of drusy quartzstained a mottled yellow. The car hadgotten stuck in the deep sand of thearroyo, and it had taken hours to ex-

tricate it. Now 1 was faced with arescue operation which would take val-uable time from my budgeted allot-ment.Besides, 1 knew it was dang erous tobe carrying away calves in one's car.My noble intent could easily be mis-construed as cattle rustling.When I approached the calf my nat-ural sympathy for distressed animalsmade the decision for me. He was awhite-face Hereford, not a week old.When 1 hoisted him to my shoulders,he gave a plaintive '"moo-oo-oo." whichwas a good sign of life.After interrogating several ranchersin the vicinity, I learned that HoracePorter ran some stock in this canyon.I drove to the Porter ranch andshowed Horace my debilitated cargo.

G a 11 o -., -- , M t n s .

" - X < V v 5 APACHE'". V > > \ i C R E P '' y S ' / X V V ' 1 ' '"'

He was grateful. The dogie was grate-ful too; especially after a number ofwild pulls on the rubber nipple theexperienced rancher had affixed to aspigot in a bucket for such a purposeas this.When P orter learned that 1 hadcome 200 miles from Albuquerque tosearch for agate, and that I had beenunsuccessful, he volunteered to takeme to the place "where 1 have riddenover sparkling rock since I was a boy."This place he called Lea RussellCanyon.The rancher also invited me to anearly supper, a night's lodging, or anynum ber of nice things. Beca use I wasequipped for cam ping, 1 accepted acompromised generosity: 1 asked himto draw a map of this spectacular can-yon. He readily obliged, and my nextday's trip was planned.Apache Creek postottice, CatronCounty, New Mexico, is the center ofthe ranching activity along the Tula-rosa River. It is reach ed from U . S.Highway 60 by two routes: from theeast, New M exico State Roa d 12 leadssouthwest from Datil, across the plainsof San Augustine, past the tiny settle-ment of Aragon, to Apache Creek;from the West it is approached on U.S. 260, a graveled road akin to NewMexico State 12, the both of themlike mother's washboard, through Lunaand Reserve, New Mexico.The Tularosa River, which fre-quently carries a small stream of water,forms a deep canyon to which ApacheCreek, Wilson Canyon, and Largo Can-yon are tributary.The combination store, filling sta-tion and postoffice which is situated atthe juncture of Apache Creek and theTularosa comprises the entire settle-men t. This enterprise is the domain ofRomeo Price, one of the area's leadingcitizens and brother to DoughbellyPrice, a well known New Mexico figure.It was late afternoon when I arrivedat M r. Price's empo rium. During thecourse of servicing the automobile andpurchasing forgotten articles of supply,I chatted with the owner. When askedwhat I was doing in these parts, I in-formed the inquisitive gentleman thatI was rock hunting.He made the classic remark, "Well,you don't have to go any farther.There's a 'hull hillside full of rocks."He pointed to drab limestone screeacross the road.I tactfully qualified the purpose ofmy visit as being a search for agate.The attendant then said, seriously,"Why don't you go up Lea Russell

18 D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

19/48

entrance to Lea Russell Ca nyon is well concealed Beneath this limestone face the author found the biggestbehind a thicket of trees. agate he had ever seen.

Ca nyon ? It's got lots of spark lers allover it." This verification of Ho racePorter's directions was reassuring.I parked for the night in the ForestService campground across from thePrice store. As I was cooking sup per,Horace Porter drove up in a muddyJeep. He had come to the store forsupplies and had seen my campfire. Iasked him to share the grub with me.He accepted a cup of coffee, and settleddown for a neighborly chat.While the cool breeze fanned the

ashes to a glow, he and I talked aboutagate, the canyons of the area and thepeople."Most of the ranchers in this areaare Mormon," he informed me. "Theirgranddaddys were called by the Churchto settle these bottoms. A caravan ofsettlers left Utah in the early '70s,crossed the Colorado at Lee's Ferry,and settled at what was called MilliganPlaza, on the San Francisco River. Itis now Reserve. They spread out fromthere, settling the towns of Alma andPleasanton. My Granddaddy home-steaded our land in the '80s."I recall my father reading to usfrom th e family Bible. Th ere was apassage in Genesis in which is men-tioned bdellium and onyx occurring inthe Land of Havilah, near the Gardenof Eden," he continued."Bdellium is what we call opal to-day," I answered."I often wondered if it was some-thing like the agate we have here. Asa boy, whenever I rode across TurkeyFlat at the head of Lea Russell Can-yon and saw all that glittering stone. Icalled them diamonds," he said.He went on to tell how the Chirica-hua Apaches under Mangas Coloradashad raided this valley in the '80s, andhow many of the people in the outly-ing ranches had been killed. His people

had somehow escaped, to return andcommence where they had left off.Apache Springs, at the head ofApache Creek Canyon, had been head-quarters for Victorio and other famousleaders of these fiercest of all south-western Indians."You will find many places in thesecanyons where the Apaches had look-out stations, usually near springs. Ihave found arrow heads, axes, andother relics," Horace said.After being assured that 1 had mydirections straight to Lea Russell Can-yon, the friendly rancher departed forhome.The tall singing pines made this adelightful place for a night's camp.Next morning 1 headed for the "L andof Havilah."After driving five miles alongApache C reek, 1 remembered Porter'sdirections: "Th e mouth of the canyonis hidden behind some big trees butonce you get to the alfalfa field, walkacross the creek and you will be stand-ing in front of it. Th e Cany on boxesfast, then you come to a trickle ofwater. Follow it to a spring. Keepgoing until you bench out, then turnto the north. Th at is where the bestrock is fou nd. " These directions tookme to the right place.While I walked up the dry washwhich was the beginning of Lea Rus-sell Ca nyo n, 1 noticed a changed geol-ogy from W ilson Canyon. There thepredominant bedrock had been mica-specked granite: here the regular, hori-

zontal layers ol sedimentaries werelargely limestone, with thin layers ofsandstone imitating the cheese in thesandwich.After passing a turn in the narrowdraw, I came upon a trickle of runningwater. Beside it, and below a face oflimestone there lay the largest singlepiece of agate I had ever seen. Wh itebands, grading into rose-purple lines,traversed the broken face of the piece,forming swirls, triangles, bird's-eyes,and a potpourri of intricate patterns.

Tiny vugs glittered with a myriad ofmicroscopic quartz crystals. I esti-mated its weight at 20 to 30 pounds.After placing this prize where I couldpick it up on my return trip I con-tinued up the easy slope.I was watching the float which lit-tered the canyon floor. Th ere wasplenty of quartz crystal, but I searchedfor the banded agate.Two little red eyes looked at mefrom b eneath a twig. It was orbic ularjasper, as red as blood, with rosy but-tons promiscuously inlaid.1 haste ned up the trail. If these findswere droppings from the table, whatmust the mother lode be like?I passed the spring and, as directed,benched out to the north side of theshallow canyon . I almost fell into alarge depression in the ea rth before Tsaw it.Three such sunken pits geometricallydelineated the site of ancient Indianbuildings. This obviously was thedwelling of some Apache stone arti-ficer. Chip s of chalced ony and a gatelittered the grou nd. A corner of bluishopal protruded from the slit which filledthe holes . It was an axe hea d, roughlychipped, with the thong-grooves clearlyvisible. Perhaps impatience, or a for-aging and hostile band of neighbors,caused the Indian to abandon his labor.F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5 19

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

20/48

Entering the Apache Forest at Horse Springs.A short distance from the Indianruin, the rock became cracked andseamed. I stopped to examine a large

seam by inserting the point of my GIpick and prying it open. A chunk ofthe rock fell away, disclosing a mineral-

P r i z e s f o t P h o i o $ n p h e n . . .Along with snow in the high desert regions and a cool nip to theair, February brings to the desert sparkling clear skies to delight thephotographer. And there will be cloudsgreat frothy billows, delicatewisps, strange long streamers, and chubby puffsfor interesting back-grounds for black and white, spectacular sunsets for color film. Pho-tographers are invited to enter their best black-and-whites of desertsubjects in Desert Magazine's Picture-of-the-Month Contest.Entries for the February contest must be in the Desert Magazineoffice. Palm Desert, California, by February 20, and the winning printswill appear in the April issue. Pictures which arrive too late forone contest are held over for the next month. First prize is $10; secondprize $5.00. For non-winning pictures accepted for publication $3.00each will be paid.

HERE ARE THE RULES1Prints for monthly contests must be black and white, 5x7 or larger, printed

o n glossy paper.2Each photograph submitted should be fully labeled as to subject, time andplace . Also technical data: camera, shutter speed, hour of day, etc.3PRINTS WILL BE RETURNED WHEN RETURN POSTAGE IS ENCLOSED.4All entries must be in the Desert Magazine office by the 20th of the contestmonth.5Contests are open to both amateur and professional photographers. DesertMagazine requires first publication rights only of prize winning pictures.6Time and place of photograph are immaterial, except that it must be from thedesert Southwest.7Judges will be selected from Desert's editorial staff, and awards will be madeimmediately after the close of the contest each month.

Address All Entries to Photo EditortDe

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

21/48

D nu

Clinton L. Hoffman of Arcadia,California, won first prize in Desert'sDecember Picture-of-the-Month con-test with this close-up photographof a tarantu la haw k. It wa s takenwith an Eastman View camera, WAGoertz Dagor lens, 1/25 second atf. 22.

*e eHistory and humor of the Westernfrontier are combined in this second-prize photo taken at Wickenburg,Arizona. Photographer Ruth Mala-

tests of Sherman Oaks, California,used a Uniflex Universal camera,1/50 second at f. 16.

F E B R U A R Y , 1 9 5 5 21

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

22/48

Many treasures are said to be hidden in the grim canyons and waterless drawsof Arizona's Superstition Mountains.L I F E O N T H E D E S E R TBy TOM MAY

SHORTLY PAST seven o'clockone morning last May, I stopped

at the roadside park near Coo-lidge Dam, Arizona, to rest a fewminutes before continuing eastwardon my vacation trip . Getting out ofmy car to stretch my legs, 1 walkedover to a man who was eating a lonebreakfast at one of the trellis shadedpicnic tables.He ate slowly, taking sardines froma small flat can and hard bread froman old cloth sack and washing themdown with long draughts of waterpoured into his rusty flat-bottomedcup from a dirty waterba g. After fin-ishing the bread and fish, he openeda can of corn and ate its contentswithout bothering to heat or cook it.The stranger's clothes were dirtyand appeared to have been worn forweeks without changing. He had amonth's growth of bearda thick matof redbut underneath his face andneck were scrubbed, as though he hadbathed and put the same clothes backon. Parked nearby was a late modelpanel truck covered with desert dustand grime.He was shy and uncommunicativeat first, but my comments on the des-ert and mountains eventually drew himout. It wa sn't long before he wastalking freelyand rt was an interest-ing story he had to tell.

Tom May had heard too much about prospectors whohad lost their lives in the Superstition Mountains to spendan y time looking for the lost Spa nish m ine. But it wa s aninteresting yarn the stranger told him, about the poisonlode on Geranimo Head.He had been prospecting the Super-stition Mountains near Phoenix the

past four weeks, he said, but with nosuccess. It was his third or fourth tripinto the country.He had hiked up La Barge Canyonto the Reddish Hills, somewhere closeto where Boulder Canyon enters LaBarge. "Thos e Reddish Hills havebeen prospected so much," he said,"they look as though someone waspreparing to plant a vegetable gardenthere. Some of the 'scratch ings' I sawwere deep tunnels extending from 10to 100 feet back into the mountain."He had climbed to the top of Ge-ronimo Head Mountain. "I came upthe rough side," he said, "using mywalking stick to part the thorny brushand pulling myself up over ledgeswhere the canyon wall went nearlystraight up . Often I had to stretch andstrain every muscle to reach a project-ing shelf and pull myself onto it."One such ledge had a frighteningsurprise on top. I pulled my chinlevel to its floor to find myself staringa giant rattlesnake right in the eye.He lay coiled in the sun, his black

forked tongue shooting out at me. Likea tortoise back into his shell I jerkedmy head down and held on for dearlife while I steadied my precariousposition on the face of the mountainwall. T turned m y walking stick aroun d

so that the larger end was extendedand, raising up as far as I dared, struckthe snake what fortunately proved afatal blow squarely on the hea d. 1continued upward and before long wassitting on the summit, looking far outover the country."

Why had he undertaken such anarduous climb in such desolate coun-try, I asked. He was looking for anarrow hidden canyon, he replied, inwhich is supposed to be buried a for-tune in Spanish gold bullion, cachedthere by Apache Indians after they hadkilled the Spaniards who had beenmining the hidden canyon for sometime.

The stranger had heard about thecanyon from a young man he had metin La Barge Canyon who had failedin several attempts to reach the top ofthe mou ntain. This young man hada fine aerial photograph of the moun-tain as a guide, and had attemptedplotting a route from it. But the pho towas deceptive; promising canyons andarroyos too often led into narrow can-yons choked with brush or dead-endedat the base of sheer cliffs.As the man talked and gestured, Inoticed his left hand and forearm wereswollen to about three times the sizeof his right and appeared to be sorean d stiff. It looked painfully injured,and I asked him about it.

22 D E S E R T M A G A Z I N E

-

8/14/2019 195502 Desert Magazine 1955 February

23/48

He rested his elbow on the table andturned his hand from side to side so Icould see the injured lim b. How ithappened proved a long story."After the Apaches massacred Pe-dro Peralta's caravan," he began, "theIndians sent their squaws back intothe Superstitions to seal all the oldmines which the Spaniards had beenworkin g. While I was sitting on thetop of Geronimo Head, scanning thecountry below with binoculars, Ispotted what I thought might be oneof these mines. I climbed down to it.It proved to be an old cave, apparentlyman-madepossibly a mine."I set to work with chisels and handdrills trying to break through what Ithought must be the mortar used by theIndian women to seal the entrance. Iworked a day and a half and moved

about five tons of rock and dirt."The second morning I noticed myhand was beginning to swell and getstiff, and then I noticed these spots."He showed me four bluish redsplotches on the back of his hand,each about the circumference of a leadpencil, the four of them forming thecorners of a two and one-half inchsquare.He obviously was worried about thehand, but when I offered to get thefirst aid kit from my car, he declined,insisting he had already done all he

could for it. I told him whe re he couldprobably find a doctor, but he said heplanned to wait until he got home toDallas, Texas, and could see his familyphysician. He said that the hand andarm, though numb and stiff, were notin the least painful.He had made cam p at Torti l la Cam p,on Canyon Lake, but he would notreveal the exact location of the oldmine in which he had been working.He said only that it was in the vicinityof Geronimo Head Mountain.His equipment was far superior tothe average prospe ctor's. He had afine photographic outfit, but had ex-posed few plates. He had taken nonotes. His mining tools were of highquality and carefully selected with effi-ciency and weight in mind.