What lies beneath: Parenting style and implicit self-esteemwbeyers/scripties2013... · What lies...

Transcript of What lies beneath: Parenting style and implicit self-esteemwbeyers/scripties2013... · What lies...

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17

www.elsevier.com/locate/jesp

What lies beneath: Parenting style and implicit self-esteem �

Tracy DeHart a,¤, Brett W. Pelham b, Howard Tennen c

a Alcohol Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, University of Connecticut Health Center, MC 6325, 263 Farmington Avenue, Farmington, CT 06030, USA

b Department of Psychology, University at BuValo, State University of New York, USAc Department of Community Medicine, University of Connecticut Health Center, MC 6325, 263 Farmington Avenue, Farmington,

CT 06030, USA

Received 24 February 2004; revised 27 October 2004Available online 27 April 2005

Abstract

The current studies extend previous research on self-esteem by examining one of the likely origins of implicit self-esteem. Threestudies showed that young adult children who reported that their parents were more nurturing reported higher implicit self-esteemcompared with those whose parents were less nurturing. Studies 2 and 3 added a measure of overprotectiveness and revealed thatchildren who reported that their parents were overprotective also reported lower implicit self-esteem. Moreover, Study 3 revealedthat mothers’ independent reports of their early interactions with their children were also related to children’s level of implicit self-esteem. In all three studies, these Wndings remained reliable when we controlled statistically for participants’ explicit self-esteem.These Wndings contribute to a growing body of literature validating the construct of implicit self-esteem. 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Implicit; Unconscious; Self-esteem; Parent–child interactions; Name-letter

Introduction

In the history of research on the self-concept, no topichas been more heavily studied than self-esteem. Presum-ably this is the case because low self-esteem is a vulnera-bility that has been linked to susceptibility to mentalillness (Bardone, Vohs, Abramson, Heatherton, &

� A Mark Diamond Dissertation research award from the State Uni-versity of New York at BuValo provided funding for this research. Prep-aration of this article was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship fromthe Alcohol Research Center, University of Connecticut Health Center.Special thanks go to Ryan Brown, Craig Colder, Sander Koole, SandraMurray, and John Roberts for helpful comments and suggestions onthis research. In addition, Ron Crans programming of the implicit mea-sure used in Study 2 was invaluable. Finally, we thank Katie Beasman,Michelle Garnier, Debra Locastro, Mena Ryley, Jamie Shein, RichelleTordoV, and Diana Wardell for their help with data collection.

* Corresponding author. Fax: +1 860 679 5464.E-mail address: [email protected] (T. DeHart).

0022-1031/$ - see front matter 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2004.12.005

Joiner, 2000; Roberts & Monroe, 1994), relationship dis-satisfaction (DeHart, Murray, Pelham, & Rose, 2003;Murray, Holmes, & GriYn, 2000; Swann, Hixon, & DeLaRonde, 1992), and even physical illness (Brown &McGill, 1989). However, all of this research has focusedon people’s explicit (consciously considered and rela-tively controlled) self-evaluations.

In recent years, however, researchers have begun tosuspect that there may be more to self-esteem than meetsthe eye. SpeciWcally, researchers have begun to focus onpeople’s implicit (i.e., unconscious, relatively uncon-trolled, and overlearned) self-evaluations (see Green-wald & Banaji, 1995, for a review). Despite the recentinterest in implicit self-evaluation, some researchersquestion the reliability and validity of measures thatassess implicit self-esteem (Bosson, Swann, & Penne-baker, 2000). Importantly, Bosson et al. suggested thatmore studies needed to be conducted to validate the con-struct of implicit self-esteem.

2 T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17

Over the past few years, a growing body of literaturehas focused on the name-letter measure of implicit self-esteem (Baccus, Baldwin, & Packer, 2004; Bosson,Brown, Zeigler-Hill, & Swann, 2003; Dijksterhuis, 2004;Jones, Pelham, Mirenberg, & Hetts, 2002; Koole,Dijksterhuis, & van Knippenberg, 2001; Pelham et al.,2005; Shimizu & Pelham, 2004) which complements pre-vious research on the name-letter eVect (Kitayama &Karasawa, 1997; Koole, Smeets, van Knippenberg, &Dijksterhuis, 1999; Nuttin, 1985, 1987). For example,Koole et al. reported that name-letter preferences (i.e.,the tendency for people to rate their name-letters morefavorably than others rate these letters) demonstratedgood temporal stability over a 4-week period (also seeBosson et al., 2000). Koole et al. also provided evidencethat name-letter preferences reXect automatic self-evalu-ations. In addition, Jones et al. (2002) demonstrated thatname-letter preferences are predictably related to self-evaluation. After a mild self-concept threat, people highin explicit self-esteem show particularly pronouncedname-letter preferences. Moreover, Dijksterhuis (2004)found that subliminally pairing self-related words withpositively valenced words enhanced people’s name-letterratings (see also Baccus et al., 2004).

Recent research has also demonstrated that implicitself-esteem predicts important psychological and physi-cal behaviors above that of explicit self-esteem. Forexample, separate research using the Implicit Associa-tion Test (IAT) and the name-letter measures of implicitself-esteem has linked the combination of high explicitand low implicit self-esteem with greater defensivenessand higher levels of narcissism (see Bosson et al., 2003for name-letter Wndings and Jordan, Spencer, Zanna,Hoshino-Browne, & Correll, 2003 for IAT Wndings). Inaddition, implicit self-esteem has been associated withphysical health above and beyond the relation betweenexplicit self-esteem and health (Shimizu & Pelham,2004). Finally, implicit self-esteem has been found to bea better predictor than explicit self-esteem of people’snon-verbal anxiety (Spalding & Hardin, 1999). Becauseimplicit self-esteem has been linked to several outcomesit seems important to determine the likely origins ofimplicit self-esteem.

In the present research, we examine one potentialorigin of implicit self-esteem, early childhoodexperiences with parents. That is, we believe people’searly interactions with their parents are associated withtheir implicit as well as explicit self-esteem. Anothergoal of the current research is to contribute to a grow-ing body of literature assessing the construct validity ofimplicit self-esteem. That is, by showing that implicitself-esteem is associated with reports of early experi-ences that should be associated with positive or nega-tive self-evaluations, we hope to provide evidence thatimplicit self-esteem is a valid, psychologically meaning-ful construct.

Development of implicit self-esteem

Like people’s explicit self-evaluations, people’simplicit self-evaluations are presumably formed throughinteractions with signiWcant others (e.g., Bartholomew,1990; Bowlby, 1982; Cooley, 1902; Leary, Tambor, Ter-dal, & Downs, 1995; Mead, 1934). Theories in the tradi-tion of symbolic interactionism suggest that peopledevelop a sense of self on the basis of how other peopletreat them (Cooley, 1902; Mead, 1934). In addition, thesociometer theory of self-esteem suggests that people’sself-esteem is formed through their interactions withothers (Leary et al., 1995). SpeciWcally, individuals withlow self-esteem have repeatedly experienced perceivedinterpersonal rejection. Conversely, most people withhigh self-esteem have experienced many subjectively suc-cessful or non-rejecting interpersonal relationships. Itseems reasonable to assume that compared with peoplehigh in implicit self-esteem, people low in implicit self-esteem may have experienced repeated interpersonalrejection.

Parents—especially mothers—loom large in the psy-chological landscapes of most children (e.g., Baumrind,1971; Bowlby, 1982; Harter, 1993; Parker, Tupling, &Brown, 1979; Pomerantz & Newman, 2000; but cf. Har-ris, 1995). For example, attachment theorists argue thatpeople develop beliefs about the self on the basis of theresponsiveness and sensitivity of their primary caregiversin childhood (e.g., Bartholomew, 1990; Bowlby, 1982).Repeated interpersonal experiences within the familythus form the basis for mental representations of the selfin relation to others. Over time, how caretakers respondto infants presumably becomes internalized into work-ing mental models, which are a set of conscious andunconscious beliefs for organizing information aboutthe self in relation to other people.

In keeping with these theoretical perspectives, itseems reasonable that parenting style should be relatedto both implicit and explicit self-esteem (Baumrind,1971, 1983). Parents who make use of an authoritativeparenting style provide their children with love and emo-tional support, as well as clearly deWned rules for what isconsidered appropriate behavior. In contrast, parentswho use an authoritarian parenting style adopt a morepunitive approach to parenting that more typicallyinvolves threats, criticism, and enforcement of unilater-ally dictated rules. In addition, parents who adopt anauthoritarian strategy do not usually provide the loveand emotional support that is characteristic of anauthoritative strategy. Finally, parents who use a permis-sive parenting style typically provide inconsistent ruleenforcement (or lack of structure). Although permissiveparents may be aVectionate, their failure to regulate theirchildren’s behavior can lead to low self-esteem becausechildren fail to learn appropriate forms of self-regulation(e.g., they may experience social rejection when they

T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17 3

engage in behaviors with others that their parents toler-ate or ignore). Thus, according to Baumrind, people whoreport having had (1) less aVectionate or nurturing inter-actions with their parents or (2) a lack of guidance andstructure may have lower implicit as well as explicit self-esteem. Authoritative parenting has consistently beenrelated to greater adolescent adjustment and psychoso-cial maturity compared with authoritarian and permis-sive parenting (Steinberg & Morris, 2001).

Another perspective on parenting style posits thatcare (i.e., nurturance) and overprotectiveness are the twoprimary parenting dimensions (Parker et al., 1997, 1979).According to this perspective, the dimension of overpro-tectiveness reXects excessive control, which probablyinterferes with the child’s ability to develop a sense ofautonomy or competence (see Gilbert & Silvera, 1996;Ryan & Deci, 2000; for related perspectives). More spe-ciWcally, overhelping or overprotection may underminechildren’s ability to take full credit for their accomplish-ments, which may result in lower self-esteem (see alsoParker et al., 1997).

Dissociation between implicit and explicit self-esteem

Because both implicit and explicit self-esteem areformed based on interactions with signiWcant others, onemight expect a high degree of congruence between peo-ple’s explicit and implicit self-evaluations. However, theexisting evidence suggests that the correlation betweenimplicit and explicit self-esteem is small at best (e.g., Bos-son et al., 2000; Hetts, Sakuma, & Pelham, 1999; Pelham& Hetts, 1999; but cf. Pelham et al., 2005).

If both explicit and implicit self-esteem arise frominteractions with signiWcant others, why are they weaklyrelated to one another? The reasons presumably have todo with diVerences in the nature of implicit and explicitbeliefs (Epstein, 1994; Pelham & Hetts, 1999). First, peo-ple’s implicit beliefs about the self are believed todevelop at an earlier age than their explicit beliefs aboutthe self (e.g., Hetts & Pelham, 2001; Koole et al., 2001).Implicit beliefs that presumably have their origins inearly childhood experiences may become automatic overtime. Because the quality of people’s relationships maychange over time and be reXected in their explicit beliefsystem, their previously formed implicit beliefs may notbe available for conscious articulation, but may still beelicited automatically.

Second, the valence and emotional tone of people’ssocial interactions with close others should leave a clearmark on their implicit self-evaluations. However, when itcomes to explicit self-evaluations, the desire to view theself favorably may cause people to ignore or reinterpretnegative social experiences (Crocker & Major, 1989;Hetts & Pelham, 2003; Pelham, DeHart, & Carvallo,2003). For example, Hetts and Pelham (2003) found thatbeing overlooked on one’s birthday was associated with

low implicit, but not low explicit, self-esteem. A thirdreason for the potential dissociation between implicitand explicit self-esteem is that, once formed, implicitself-esteem appears to change much more slowly thanexplicit self-esteem. In a study of acculturation and self-esteem, Hetts et al. (1999) demonstrated that whereasAsian Americans’ explicit self-esteem changed veryquickly when they immigrated to the US, their traitimplicit self-esteem scores changed much more slowly. Infact, their trait implicit self-esteem scores appear to haveincreased slowly over a 10-year period.

Although the above evidence suggests that someexperiences (such as being overlooked on one’s birth-day) can be consciously explained away, experiencesthat are more pervasive (such as moving to a new cul-ture) can inXuence both explicit and implicit self-esteem (although change occurs more quickly forexplicit self-esteem). Consistent with this idea, the qual-ity of parent–child interactions, which are long lasting,begin early in life, and may be diYcult to explain away(especially for young children), should be uniquelyrelated to people’s implicit as well as explicit self-esteem.

Study 1

In Study 1, we hoped to extend previous work onimplicit self-esteem by assessing whether people’simplicit self-evaluations were related to their self-reported interactions with their parents. SpeciWcally, weexpected that people who reported more negative inter-actions with their parents would have lower implicit self-esteem compared with those who reported more positiveinteractions. We had the same expectations for explicitself-esteem. In addition, we wanted to extend previouswork on implicit self-esteem by taking multiple measuresof implicit self-esteem to help improve the reliability andpredictive validity of the measure (i.e., Bosson et al.,2000). This could prove to be very important because acommon criticism of research on implicit self-esteem(and implicit social cognition more broadly) is thatimplicit measures often suVer from questionablereliability.

Method

ParticipantsTwo hundred and nineteen students in an introduc-

tory social psychology course at the State University ofNew York at BuValo participated for course credit. Par-ticipation was voluntary and anonymous. Studentsreceived extra course credit for attending class on eachof the two occasions on which questionnaires wereadministered, even if they chose not to participate. Meanage was 21.25 years (SD D 2.42). We were unable to use

4 T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17

data from 60 students because they did not attend classthe day the second questionnaire was administered, leav-ing 110 women and 49 men in the sample.1

Overview of procedureDuring a regular class session, students took part in a

survey that focused on their “attitudes and family rela-tionships.” Participants completed an explicit measureof self-esteem, self-concept clarity, a name-letter mea-sure of implicit self-esteem, and a childhood experiencesquestionnaire. At the end of the survey, they reportedtheir Wrst and last name initials. Six weeks later, partici-pants completed a follow-up survey containing thesame explicit measure of self-esteem, name-letter mea-sure, and childhood experiences questionnaire. We kepttrack of participants’ responses using conWdential codenumbers.

MeasuresExplicit self-esteem. We used Rosenberg’s (1965) 10-item self-esteem scale that taps explicit global self-evalu-ations (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good quali-ties”). Participants responded using a seven-point scale(1 D completely true, 7 D not at all true). Negative itemswere reverse-scored, such that higher scores indicatedhigher self-esteem (see the top of Table 1 for the means,standard deviations, and reliabilities for this and thefollowing measures2).

Self-concept clarity scale. This 12-item scale measuresthe extent to which the contents of an individual’s self-concept are clearly and conWdently deWned, internallyconsistent, and temporally stable (Campbell et al., 1996).Responses were given on a seven-point scale(1 D strongly disagree, 7 D strongly agree). Negativelyworded items were reverse-scored so that higher scoresrepresent higher self-concept clarity.

Implicit self-esteem. The measure of implicit self-esteemwas based on research on the name-letter eVect (Kitay-ama & Karasawa, 1997; Nuttin, 1985, 1987). SpeciWcally,participants’ implicit evaluation of their name-letter ini-tials was assessed by asking them to rate their prefer-ences for all of the letters of the alphabet. Participantswere told that their ratings would be used to “developstimuli for future studies of linguistic and pictorial pref-erences.” Participants were further told to “trust yourintuitions, work quickly, and report your “gut impres-sions” (Jones et al., 2002). Preference ratings were madeon a nine-point scale (1 D dislike very much, 9 D like very

1 The students who provided complete data did not diVer signiWcant-ly from the students we had incomplete data from on any of the self-concept or parenting variables.

2 The implicit self-esteem measure has a slightly lower � than the oth-er measures because this indicator only has two items.

much). We computed people’s preference for their name-letters by computing a baseline liking for each letter forparticipants whose initials do not include that letter (forinformation on scoring and validity, see Koole et al.,2001). Next, we computed a liking score that was thediVerence between participants’ rating of their Wrst andlast name initials and the relevant baseline preferencescore (positive numbers indicate stronger name-letterpreferences). Participants’ name-letter preferences werecomputed by taking the average of their liking scores fortheir Wrst and last name initials. This name-letter mea-sure demonstrated acceptable test–retest reliability overthe 6-week period, r (145) D .60, p < .01. Thus, we aver-aged the Time 1 and Time 2 implicit self-esteem scores toproduce a single implicit self-esteem score (�D .75).

Childhood experiences measure. Participants completedmeasures that assessed the type of parenting style theirparents used when they were growing up. We con-structed these measures based on Baumrind’s (1971) the-ory of parenting styles (and we pilot tested them forreliability prior to their use in this study). Seven of thequestions focused on an authoritative parenting style(e.g., “My mother explained the reasons for the rules sheestablished”), seven focused on an authoritarian parent-ing style (e.g., “My mother withdrew her love when Imisbehaved or broke a rule”), and seven focused on apermissive parenting style (e.g., “My mother let me dopretty much what I pleased”). Participants answeredthese questions separately for their mothers and fathers

Table 1Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations for the mea-sures used in Study 1

¤ p < .05.¤¤ p < .01.

9 p < .10.

Measures Mean SD �

Time 1Explicit self-esteem 5.63 1.09 .90Self-concept clarity 4.30 1.28 .88Implicit self-esteem 1.52 1.53 .61Authoritative 6.61 1.77 .95Authoritarian 3.00 1.56 .88Permissive 3.55 1.29 .79

Time 2Explicit self-esteem 5.78 1.01 .91Implicit self-esteem 1.63 1.55 .52Authoritative 6.77 1.65 .96Authoritarian 3.00 1.58 .89Permissive 3.65 1.36 .83

CorrelationsVariables 1 2 3 4

1. Quality of parenting .21¤ .45¤¤ .45¤¤

2. Implicit self-esteem .159 .033. Explicit self-esteem .72¤¤

4. Self-concept clarity

T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17 5

using nine-point scales (1 D rarely or never; 9 D very fre-quently). Reports about mothers and fathers were aver-aged, and the authoritative, authoritarian, andpermissive scales demonstrated good test–retest reliabil-ity over the 6-week test period, respectively, rs D .91, .88,and .83, all ps < .01.

Results

To determine whether the parenting variables couldbe reduced to a smaller number of dimensions, we con-ducted an exploratory factor analysis on an average ofparticipants’ Time 1 and Time 2 reports of parenting.The factor analysis suggested that the parenting vari-ables could be reduced to a single factor that accountedfor 63.22% of the variance, which we labeled quality ofparenting. Next, scores on the authoritarian and permis-sive parenting dimensions were recoded (so that higherscores reXected a more favorable parenting style), andthe three parenting subscales were combined (� D .71) tocreate a single quality of parenting index.3

Was this quality of parenting score associated withchildren’s implicit self-esteem scores (see bottom ofTable 1 for the correlations between quality of parentingand the self-concept indicators)? Using AMOS, thestructural equation-modeling program within SPSS forWindows, we constructed a model that allowed anassessment of the unique association between quality ofparenting and participants’ implicit self-esteem indepen-dent of any association between parenting and explicitself-esteem (see Fig. 1 for a conceptually similar model).As expected, path a linking participants’ reports of theirparents’ parenting styles was related to their level ofimplicit self-esteem, B D .24, �D .21, z D 2.51, p D .01.Those who reported that they had more positive interac-tions with their parents had higher implicit self-esteem.More important, this relation was signiWcant controllingfor the path between parenting and explicit self-esteem(path b), B D .41, �D .44, z D 5.64, p < .01, and the pathbetween implicit and explicit self-esteem (path c),B D .02, � D .03, z D .33, p D .74.4 In addition, the samepattern emerged when we substituted participants’ self-concept clarity scores (a conceptually similar explicitself-concept indicator) for their explicit self-esteemscores.5

3 There was a moderate correlation between the students’ reports oftheir mothers’ and fathers’ quality of parenting, r (150) D .51, p < .01. Inaddition, separate factor analyses on the students’ reports of theirmothers’ and fathers’ parenting are identical to the one for the com-bined indicators.

4 We drew the causal arrow from implicit to explicit self-esteem becausetheory suggests that people’s implicit self-esteem develops earlier thantheir explicit self-esteem (Koole et al., 2001). If we draw the causal arrowfrom explicit to implicit self-esteem we see a similar pattern of results.

5 There were no signiWcant gender diVerences in the relation betweenparenting and implicit self-esteem across the three studies.

Discussion

Study 1 provides what we believe to be the Wrst evi-dence that people’s recollections of their early interac-tions with their parents are related to their level ofimplicit self-esteem. SpeciWcally, participants whorecalled having had more nurturing and caringinteractions with their parents also reported higherimplicit self-esteem. In addition, the relation betweenimplicit self-esteem and self-reported interactions withparents was signiWcant even after controlling for partici-pants’ level of explicit self-esteem and self-concept clarity.

One of the strengths of Study 1 is that we developed areliable, temporally stable indicator of perceived parent-ing style. The fact that our measure of parenting pre-dicted explicit as well as implicit self-esteem supports itsvalidity. On the other hand, we observed one parentingfactor rather than the three we anticipated. In Study 2, weemployed a measure of parenting style for which substan-tial validity data already exist, and we attempted to repli-cate and extend the Wndings of Study 1 by examining twoadditional dimensions of parenting—caring and overpro-tectiveness. Based on previous research on these parent-ing dimensions (Parker et al., 1979, 1997), we expectedthat people who reported that their parents engaged inmore caring (i.e., nurturing) behaviors would have higherimplicit self-esteem. In addition, we expected that peoplewho reported that their parents were more overprotectivethan most would have lower implicit self-esteem.

Study 2

In Study 2, we examined multiple indicators ofpeople’s interactions with their parents to try anddetermine which speciWc dimensions of parenting areassociated with people’s implicit self-esteem. Parkeret al. (1979) identiWed two factors that consistentlyemerged as core dimensions of parenting: (a) aVectionand warmth and (b) psychological control. In keepingwith these Wndings, we supplemented our original par-enting measures by adding Parker et al.’s well-vali-dated measures of each of these two parentingdimensions in Study 2.

Because we only assessed implicit self-esteem on oneoccasion in Study 2 we also assessed an additional indi-cator of implicit self-esteem—people’s birthday-numberpreferences (i.e., people’s liking for the numbers corre-sponding to the day and month they were born).Although diVerent measures of implicit self-esteem areoften uncorrelated with one another (Bosson et al.,2000), the available evidence suggests that name-letterpreferences and birthday-number preferences are signiW-cantly correlated (Bosson et al., 2000; Jones et al., 2002;Koole et al., 2001). The reason for this correlationbetween name-letter and birthday-number preferences is

6 T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17

likely due to the similarity in the type of cognitive pro-cessing required to complete the two measures (Koole &Pelham, 2002; see also Dijksterhuis, 2004).

Method

ParticipantsStudents (53 women and 32 men) enrolled in an intro-

ductory psychology course at Colgate University partici-pated in a study on close relationships in exchange forcourse credit. The students’ mean age was 19.5(SD D .72).

ProcedureUpon arriving at the laboratory, participants were

escorted to individual cubicles containing a Macin-tosh computer. Upon completing measures of explicitself-esteem and self-concept clarity, participants com-pleted computerized name-letter and birthday-number measures of implicit self-esteem. Participantswere then asked to report their Wrst and last name ini-tials as well as their birthdays on the computer.Finally, they completed the childhood experiencesquestionnaires.

MeasuresExplicit self-esteem and self-concept clarity. We used thesame explicit self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965) and thesame self-concept clarity scale (Campbell et al., 1996)that we used in Study 1 (respectively, �s D .89 and .90).

Implicit self-esteem. Study 2 made use of a computer-ized version of the name-letter measure used in Study 1as well as a birthday-number measure of implicit self-esteem. Participants Wrst reported their preferences forthe numbers 1–33. The numbers 33 and 32 were pre-sented Wrst, after which the other 31 numbers were pre-sented randomly. Next, participants reported theirpreferences for the 26 letters of the alphabet. The let-ters X and Z were always presented Wrst, after whichthe other letters were presented randomly. Participantsreported their liking for each individual characterusing the number pad on their computer keyboards(1 D dislike very much, 9 D like very much). To computeimplicit self-esteem we Wrst separately computedname-letter and birthday-number preferences (by aver-aging participants’ Wrst and last name initial prefer-ences as well as their month of birth and day of birthpreferences). Surprisingly, participants total name-let-ter liking scores were not signiWcantly correlated withtheir total birthday-number liking scores, r (79) D .17,p D .12. Nonetheless, because past research has typi-cally found a relation between these two implicit mea-sures (Bosson et al., 2000; Koole et al., 2001), andbecause they appear to behave in a very similar fashion(Jones et al., 2002) we combined them into a single

index of implicit self-esteem (see also Baccus et al.,2004).6

Childhood experiences measure. Study 2 made use of thesame parenting style measure used in Study 1. Theauthoritative, authoritarian, and permissive subscales allhad good internal reliability (respectively, �’s D .93, .84,and .70).

Parental bonding inventory. Participants also completedParker et al.’s (1979) 25-item measure of two dimensionsof parents’ interaction styles: caring (nurturance) andoverprotectiveness. The caring subscale consisted of 12items (e.g., “My mother spoke to me in a warm andfriendly voice”) and the overprotective subscale con-sisted of 13 items (e.g., “My mother tried to controleverything I did” and “My mother was overprotective ofme”). Participants answered these questions about theirmothers and fathers using four-point scales (1 D veryunlike, 4 D very like). Reports about mothers and fatherswere averaged, and the caring and overprotectivenesssubscales both had good internal reliability (respectively,�’s D .95 and .84).

Results

To determine whether the Wve scale scores that collec-tively made up the Parental Bonding Inventory and theChildhood Experiences Measure could be reduced to asmaller number of meaningful dimensions, we conducteda series of factor analyses. An exploratory factor analysiswith an oblique rotation suggested that the Wve parentingvariables could be reduced to two factors accounting for79.42% of the variance. The Wrst factor consisted of theauthoritative, authoritarian, caring, and overprotectivesubscales (with negative loadings for authoritarianismand overprotectiveness). The second factor was the per-missive parenting subscale, although the overprotectivesubscale also loaded highly on this factor. Because theoverprotective subscale loaded highly on both factors, weconducted a conWrmatory factor analysis on the authori-tative, authoritarian, caring, and overprotective subscalesthat made up the Wrst factor to determine whether a one-factor model adequately Wts these subscales. The resultssuggest that a one-factor model did not adequately Wt thedata, �2 (2) D 40.55, p < .01, �2/df D 20.28, CFI D .82,NFI D .82. An inspection of the factor loadings revealedthat the overprotective subscale failed to have an ade-quate loading on the parenting factor (e.g., standardized

6 We combined these two implicit measures because we believe thattwo weakly related variables can indeed both be assessing implicit self-esteem (for a related argument on implicit memory see Buchner &Wippich, 2000; Perruchet & Baveux, 1989). In addition, because pastresearch typically Wnds a signiWcant relation between these measureswe wanted to take a conservative approach and combine them.

T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17 7

loading D¡.32). Therefore, we removed the overprotec-tive subscale from the Wrst factor. In addition, because theoverprotective and permissive subscales were uncorre-lated with one another, r (80) D¡.08, p D .50, we treatedeach subscale as a separate factor. Nonetheless, it isworth noting that analyses in which we combined all Wvefactors into a single factor yielded results very similar tothose we report below.

The three resulting factors were labeled: (a) nurtur-ance, (b) overprotectiveness, and (c) permissiveness (seeTable 2 for the correlations between these parentingvariables and the self-concept indicators).7 Scores on theauthoritarian dimension were recoded (so that higherscores reXected a more favorable parenting style), andthe three subscales that made up the nurturance factor(authoritative, authoritarian, and caring) were standard-ized and then combined. The resulting scale had goodinternal reliability (�D .88).

Is parenting related to implicit self-esteem?Did the parenting variables predict children’s implicit

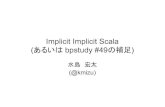

self-esteem? As summarized in Fig. 1, path a linkingparental nurturance to implicit self-esteem was signiW-cant. SpeciWcally, participants who reported that their

7 Students’ reports of their mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styleswere correlated with one another for nurturance, overprotectiveness,and permissive, respectively, rs D .51, .49, and .52, ps < .01. In addition,separate factor analyses on the students’ reports of their mothers andfathers parenting are identical to the ones we reported in the paper forthe combined indicators of parenting.

Table 2Correlations between the parenting and self-concept variables used inStudy 2

¤ p < .05.¤¤ p < .01.

9 p < .10.

Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6

1. Nurturance ¡.47¤¤ ¡.219 .33¤¤ .32¤¤ .39¤¤

2. Overprotectiveness ¡.08 ¡.28¤ ¡.16 ¡.29¤¤

3. Permissiveness ¡.05 ¡.29¤¤ ¡.154. Implicit self-esteem .22¤ .26¤

5. Explicit self-esteem .60¤¤

6. Self-concept clarity

Fig. 1. The relation between children’s reports of parental nurturanceand implicit self-esteem controlling for explicit self-esteem (Study 2).

parents were more nurturing had higher implicit self-esteem compared with those who reported that theirparents were less nurturing. Most important, this rela-tion was signiWcant controlling for the positive relationbetween parental nurturance and explicit self-esteem(path b) and the relation between implicit and explicitself-esteem (path c).

In addition, we found that participants’ level ofimplicit self-esteem was related to how overprotectivethey reported their parents were while they were growingup (see Fig. 2 for coeYcients). SpeciWcally, participantswho reported that their parents were more overprotec-tive had lower implicit self-esteem compared with chil-dren who reported that their parents were lessoverprotective. However, there was no signiWcant rela-tion between overprotectiveness and explicit self-esteem.The association between overprotectiveness and implicitself-esteem also remained signiWcant controlling forexplicit self-esteem.

Surprisingly, participants’ level of implicit self-esteemwas unrelated to their reports of how permissive theirparents were while they were growing up (see Fig. 3 forcoeYcients). However, their level of explicit self-esteemwas related to their reports of parental permissiveness(path b). That is, participants who reported that theirparents had been more permissive had lower explicitself-esteem compared with children who reported that

Fig. 2. The relation between children’s reports of parental overprotec-tiveness and implicit self-esteem controlling for explicit self-esteem(Study 2).

Fig. 3. The relation between children’s reports of parental permissivenessand implicit self-esteem controlling for explicit self-esteem (Study 2).

8 T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17

their parents had been less permissive. Consistent withthe Wndings from Study 1, the same pattern of resultsemerged for all three parenting variables when we substi-tuted participants’ self-concept clarity scores for theirexplicit self-esteem scores.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 replicate and extend the Wnd-ing that implicit self-esteem is related to people’sreports of their early experiences with their parents.Consistent with previous research on the structure ofparenting (Parker et al., 1979), the dimensions of nur-turance and overprotectiveness appeared to be the twomost important components of parenting. SpeciWcally,individuals who reported that their parents had beenmore nurturing had higher implicit and explicit self-esteem compared with people who recalled their par-ents had been less nurturing. In addition, students whoperceived that their parents had been more versus lessoverprotective had lower implicit self-esteem. How-ever, overprotectiveness was unrelated to explicit self-esteem. Surprisingly, parental permissiveness wasunrelated to implicit self-esteem. However, permissive-ness was signiWcantly, and negatively, related toexplicit self-esteem. Thus, the null Wndings for permis-siveness do not appear to reXect a limitation in themeasure of this component of parenting. Study 3 wasconducted in part to further examine this discrepancyin the associations between permissiveness and implicitversus explicit self-esteem.

Study 2 also raised some questions about the best wayto assess implicit self-esteem. That is, when we separatelylook at the Wndings for name-letter and birthday-num-ber preferences we only observed a signiWcant pattern ofresults when looking at birthday-number preferences.That is, the relation between students’ reports of paren-tal nurturance and birthday-number preferences was sig-niWcant, B D .59, � D .29, z D 2.65, p < .01 (controlling forexplicit self-esteem) as was the relation between stu-dents’ reports of parental overprotectiveness and birth-day-number preferences B D ¡1.10, �D ¡.26, z D ¡2.40,p < .05 (controlling for explicit self-esteem). When welooked only at the name-letter measure, we observed anon-signiWcant pattern of results in the same directionfor both nurturance, B D .25, �D .15, z D 1.34, p D .18,and overprotectiveness, B D ¡.20, � D ¡.06, z D ¡.52,p D .60. Consistent with our previous Wndings, students’reports of parental permissiveness were unrelated toimplicit self-esteem for both the birth-date and name-let-ter measures of implicit self-esteem.

The Wnding that the relation between parenting andimplicit self-esteem was weaker for the name-lettermeasure (alone) in Study 2 may seem inconsistent withthe Wndings from Study 1. However, in Study 1, weassessed name-letter ratings on two occasions. We

assume that although implicit self-esteem may varyfrom moment to moment, most people possess achronic level of implicit self-esteem (see Hetts & Pel-ham, 2001). At Wrst blush the idea that implicit self-esteem can be both highly stable and highly malleableseems paradoxical. Nonetheless, there are many physi-cal as well as psychological constructs that have theseproperties. For example, although blood pressure andpulse rate can vary dramatically from moment tomoment (e.g., because of exercise), everyone has achronic blood pressure level. In the case of implicitself-esteem, the easiest way to clarify this importantdistinction is to recognize the diVerence between anindividual’s trait versus state level of implicit self-esteem. Presumably, the ideal way to assess a person’slevel of trait implicit self-esteem would be to assessimplicit self-esteem on numerous occasions, taking anaverage across all of these occasions. Moreover,regardless of one’s view of the malleability of implicitself-esteem, basic psychometric considerations suggestthat researchers interested in assessing any trait woulddo well to assess this trait on multiple occasions. InStudy 3, we addressed this issue by assessingparticipants’ name-letter preferences on multipleoccasions.

Finally, although the results of Studies 1 and 2suggest that the quality of people’s early childhoodexperiences is related to their level of implicit self-esteem, there is an important alternative explanationfor these Wndings. SpeciWcally, people’s current beliefsand feelings about the self could tarnish their reportsof their childhood experiences with their parents. Thatis, there is good evidence that people’s current beliefsabout the self can inXuence the imagined appraisals ofothers (Kenny, 1994; Shrauger & Schoeneman, 1979).In addition, there is evidence that adult children withlow self-esteem underestimate how much their mothersactually love them (DeHart et al., 2003). Therefore, ifpeople’s explicit beliefs about the self can bias theirperceptions of their current or past relationships, it ispossible, in principle, that their implicit beliefs can dothe same. Therefore, in Study 3 we obtained indepen-dent parenting style reports from participants’ moth-ers, in addition to their own reports of her parentingstyle.

Study 3

In Study 3, we tried to replicate and extend the Wnd-ings from Studies 1 and 2 by repeatedly assessingimplicit and explicit self-esteem and making use of bothparticipants’ self-reports of their mothers’ parentingbehaviors and mothers’ reports of their own parentingbehaviors. Having multiple indicators of implicit andexplicit self-esteem, as well as the parenting variable we

T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17 9

labeled nurturance, allowed us to create latent variablesthat we could use to model the relation between parent-ing and self-esteem. In addition, we wanted to reassessthe structure of the parenting factors observed in Study2 and reassess the relation between these parenting fac-tors and implicit self-esteem. Finally, we wanted to repli-cate the Wndings of Study 2 by seeing if: (a) nurturancewould be related to both implicit and explicit self-esteem, (b) overprotectiveness would be related toimplicit, but not explicit self-esteem, and (c) permissive-ness would be related to explicit, but not implicit self-esteem.

Method

ParticipantsChildren. Students (190 women and 119 men) enrolled inan introductory social psychology course at the StateUniversity of New York at BuValo participated in theWrst phase of a study on close relationships. The stu-dent’s mean age was 21.9 (SD D 3.9). Participantsreceived extra course credit for participating.

Mothers. Two hundred and seventeen mothers of thechildren in our study participated in a study on closerelationships. Mothers’ mean age was 48.4 (SD D 6.6).

ProcedureChildren. During a regular class session, students pro-vided demographic information and completed mea-sures of explicit self-esteem and self-concept clarity, aname-letter measure of implicit self-esteem, and the twosets of parenting measures used in Study 2. Then, everyTuesday and Thursday for three consecutive weeks, par-ticipants completed a daily record that included a mea-sure of state explicit self-esteem and a name-lettermeasure of implicit self-esteem. At the end of the study,participants were asked to report their Wrst and lastname initials.

Mothers. On the day of the fourth assessment, all thoseattending lecture were asked to address an envelope totheir mothers (238 children did so). The mothers wereinformed that if they returned a conWdential question-naire, their child would receive one extra credit pointtoward the Wnal course grade. Two hundred and seven-teen mothers (91%) returned questionnaires. Themother’s surveys were patterned directly after the por-tion of the children’s surveys that focused on parenting.The data from 154 mother–child dyads were used for theanalyses.8

8 The children who provided complete data did not diVer signiWcant-ly from the children we had incomplete data from on any of the parent-ing or self-concept variables.

Background measuresTrait explicit self-esteem. Study 3 made use of the sameexplicit self-esteem measure used in Studies 1 and 2 (seeTable 3 for the means, standard deviations, and reliabili-ties for this and the following measures).

Childhood experiences measure. Children Wlled out thesame parenting style questionnaire used in Studies 1and 2. In addition, mothers completed rewordedversions of this measure (e.g., “I explained the reasonsfor the rules I established,” “I withdrew my lovewhen my child misbehaved or broke a rule,” and “I letmy child do pretty much anything she/he pleased”).Both children and mothers answered these questionson nine-point scales (1 D rarely or never; 9 D veryfrequently).

Parental bonding inventory. Children also completed thesame parents’ interaction styles survey used in Study 2(Parker et al., 1979). Mothers Wlled out reworded ver-sions of this measure (e.g., “I spoke to my child in awarm and friendly voice” and “I tried to control every-thing my child did”). Both children and mothersanswered these questions on a four-point scale (1 D veryunlike, 4 D very like).

Repeated measuresState self-esteem. An adapted version of the RosenbergSelf-esteem Scale was used to assess state self-esteem(Rosenberg, 1965) during each of the six classroom ses-sions (Kernis, Cornell, Sun, Berry, & Harlow, 1993).Participants were instructed to report how they werefeeling about themselves at this moment (e.g., “At thismoment, I feel that I have a number of good qualities),

Table 3Means, standard deviations, and reliabilities for the primary measuresused in Study 3

Measures Mean SD �

ChildrenTrait explicit self-esteem 5.65 1.08 .91Authoritative 6.79 1.94 .94Authoritarian 2.90 1.64 .82Permissive 3.58 1.43 .76Caring 3.30 .69 .94Overprotective 2.01 .56 .84

Children repeated measuresFirst initial liking 1.89 2.03 .90Last initial liking 1.42 2.16 .90State explicit self-esteem 5.87 1.11 .93

MothersAuthoritative 8.06 .87 .85Authoritarian 2.28 1.21 .79Permissive 3.28 1.27 .77Caring 3.62 .33 .73Overprotective 1.99 .40 .70

10 T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17

using a seven-point scale (1 D disagree very much,7 D agree very much). Negatively worded items werereverse-scored so that higher scores reXected higherstate self-esteem.

Implicit self-esteem. The name-letter measure of implicitself-esteem was administered during each of the six class-room sessions (Kitayama & Karasawa, 1997; Nuttin,1985, 1987). We averaged participants Wrst and lastinitial liking across the six assessments to produce singleindicators of these two scores.

Results

Factor analyses were conducted to determinewhether the Wve parenting subscales could be reducedto a smaller number of meaningful dimensions. The

same exploratory factor analysis we conducted inStudy 2 yielded a virtually identical factor structure,yielding two factors accounting for 79.42% of the vari-ance. The Wrst factor consisted of the authoritative,authoritarian, and caring subscales. The second factorincluded the overprotective and permissive parentingsubscales. Consistent with the Wndings of Study 2, theoverprotective and permissive parenting subscaleswere uncorrelated with one another r (152) D ¡.09,p D .25. Therefore, we again placed the overprotectiveand permissive subscales into two separate factorsreducing the parenting variables to three factorslabeled: (a) nurturance, (b) overprotectiveness, and (c)permissiveness.

We reduced the mother’s data to the same three fac-tors as the children’s data, and this factor structure wassupported with a factor analysis accounting for 68.92%

Table 4Correlations between children and mothers’ reports of parenting and children’s self-concept variables used in Study 3: children above the diagonal,mothers below the diagonal

¤ p < .05.¤¤ p < .01.9 p < .10.

Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6

1. Nurturance ¡.21¤¤ ¡.20¤ .23¤¤ .31¤¤ .19¤

2. Overprotectiveness ¡.23¤¤ ¡.09 ¡.20¤ ¡.29¤¤ ¡.23¤¤

3. Permissiveness ¡.34¤¤ .08 ¡.05 ¡.09 ¡.114. Implicit self-esteem .22¤¤ ¡.20¤ ¡.08 .18¤ .22¤¤

5. Explicit trait self-esteem .31¤¤ ¡.10 ¡.149 .18¤ .66¤¤

6. Self-concept clarity .21¤¤ ¡.16¤ ¡.03 .22¤ .66¤¤

Table 5Factor loadings and Wt indices for children’s hybrid models predicting implicit self-esteem from parenting controlling for explicit self-esteem (Study 3)

Note. GFI, Jöreskog-Sörbom Goodness of Fit Index; NFI, Bentler–Bonett Normed Fit Index; RMSEA, Browne and Cudeck Root Mean SquareError of Approximation.

a Standardized estimates are presented.

Latent factor Factor loadings for parenting modelsa

Nurturance Overprotectiveness Permissiveness

NurturanceAuthoritative .92Authoritarian ¡.76Caring .95

Implicit self-esteemAverage Wrst initial .61 .64 .56Average last initial .82 .77 .88

Explicit self-esteemTrait self-esteem .90 .83 .88State self-esteem .97 1.05 .99

Goodness of Wt summaryModel �2 df p �2/df GFI NFI RMSEA

Nurturance 17.07 11 .11 1.55 .97 .97 .06Overprotective 2.23 3 .53 .74 .99 .99 .00Permissive 1.24 3 .74 .41 1.0 .99 .00

T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17 11

of the data.9 Table 4 presents the correlations betweenchildren (above diagonal) and mothers’ (below diago-nal) reports of parenting and the children’s self-conceptvariables.

Children’s reports of parenting styles and implicit self-esteem

Because we had multiple parenting indicators forour nurturance parenting factor (authoritative,authoritarian, and the care subscales), two indicatorsof explicit self-esteem (trait self-esteem and the averageof the six explicit state self-esteem assessments), andtwo indicators of implicit self-esteem (average Wrstname liking across the six assessments and average lastname liking across the six assessments) we used theseindicators to create latent variables for nurturance,implicit self-esteem, and explicit self-esteem.10 UsingAMOS, we constructed a series of hybrid structuralequation models with latent variables (Kline, 1998) todetermine whether children’s report of their mother’s

9 Children’s reports of their mothers’ parenting styles were correlat-ed with the mothers’ reports of their own parenting styles for nurtur-ance, overprotectiveness, and permissive, respectively, rs D .55, .30, and.29, ps < .001.10 We did not include all six measures of state explicit self-esteem as

separate indicators in our latent model because only participants whowere present for all six assessments would have been included in ouranalyses—which would only have left slightly over half of our samplesize. Because we believe that participants have a fairly stable level oftrait self-esteem around which their state self-esteem Xuctuates, weused the average of each person’s state self-esteem scores in our model.We also followed this logic for our average Wrst and last name initialindicators of implicit self-esteem.

parenting styles were related to children’s implicitself-esteem. We Wrst predicted children’s implicit self-esteem from nurturance and their own explicit self-esteem (see the top left side of Table 5 for the factorloadings). Consistent with the results of Study 2, path alinking children’s reports of mothers’ nurturance toimplicit self-esteem was signiWcant, B D .16, � D .26,z D 1.98, p D .05. Latent scores on children’s reports ofthe nurturance dimension were positively associatedwith the latent score for implicit self-esteem. Mostimportant, this relation was signiWcant controlling forthe positive relation between nurturance and explicitself-esteem (path b), B D .22, � D .40, z D 4.45, p < .01,and the relation between implicit and explicit self-esteem (path c), B D .10, � D .11, z D 1.20, p D .23. Thebottom portion of Table 5 provides convergent evi-dence from several Wt indices suggesting that this andthe following hybrid models are a good Wt to the data.

The next model we constructed used our single indi-cator of overprotectiveness (see the middle of Table 5 forthe factor loadings). As expected, children who reportedthat their mothers were more overprotective had lowerimplicit self-esteem compared with children whoreported their mothers were less overprotective,B D ¡.47, �D ¡.23, z D ¡1.95, p D .05. Again, this rela-tion was signiWcant controlling for the negative relationbetween overprotectiveness and explicit self-esteem,B D ¡.54, �D ¡.34, z D ¡3.69, p < .01, and the relationbetween implicit and explicit self-esteem, B D .08, �D .10,z D 1.14, p D .26. The only diVerence between these Wnd-ings and those from Study 2 is that overprotectivenesswas related to explicit self-esteem.

Table 6Factor loadings and Wt indices for mother’s hybrid models predicting children’s implicit self-esteem from parenting controlling for explicit self-esteem (Study 3)

Note. GFI, Jöreskog-Sörbom Goodness of Fit Index; NFI, Bentler–Bonett Normed Fit Index; RMSEA, Browne and Cudeck Root Mean SquareError of Approximation.

a Standardized estimates are presented.

Latent factor Factor loadings for parenting modelsa

Nurturance Overprotectiveness Permissiveness

NurturanceAuthoritative .84Authoritarian ¡.63Caring .79

Implicit self-esteemAverage Wrst initial .77 .88 .52Average last initial .64 .56 .95

Explicit self-esteemTrait self-esteem .92 1.03 .79State self-esteem .95 .85 1.11

Goodness of Wt summaryModel �2 df p �2/df GFI NFI RMSEA

Nurturance 9.57 11 .57 .87 .98 .98 .00Overprotective 2.91 3 .41 .97 .99 .99 .00Permissive 2.83 3 .42 .94 .99 .99 .00

12 T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17

Finally, we constructed a model predicting implicitself-esteem from the permissiveness variable (see theright side of Table 5). Consistent with the Wndings fromStudy 2, children’s level of implicit self-esteem was unre-lated to their reports of how permissive their mother’swere, B D ¡.03, � D ¡.05, z D ¡.52, p D .60. However,unlike the results of Study 2, children’s reports of theirmothers’ permissiveness were not signiWcantly related totheir explicit self-esteem (though the trend was in thesame direction as in Study 2), B D ¡.07, � D ¡.12,z D ¡1.41, p D .16. However, the relation between chil-dren’s level of implicit and explicit self-esteem was mar-ginally signiWcant, B D .19, �D .19, z D 1.90, p D .06.

Mothers’ reports of parenting styles and their children’s implicit self-esteem

Did a parallel pattern of results emerge for mothers?With a few minor exceptions, the Wndings for motherswere identical to those for children (see Table 6 for all fac-tor loadings and Wt indices). Fig. 4 presents the standard-ized coeYcients for the relation between mother’s reportof their own level of nurturance and children’s implicitand explicit self-esteem scores. Mothers who reported thatthey were more nurturing had children with higherimplicit self-esteem. The path between mothers’ reports of

Fig. 4. The relation between mother’s reports of nurturance and chil-dren’s implicit self-esteem controlling for their explicit self-esteem(Study 3).

Fig. 5. The relation between mother’s reports of overprotectivenessand children’s implicit self-esteem controlling for their explicit self-esteem (Study 3).

nurturance and their children’s implicit self-esteem wassigniWcant controlling for children’s explicit self-esteem.

The results for mothers’ reports of overprotectiveness(see Fig. 5) and permissiveness (see Fig. 6) were alsoalmost identical to those for children. Mothers whoreported that they were more overprotective had chil-dren with lower implicit self-esteem compared withmothers who were less overprotective. However, unlikethe Wndings based on children’s report of parenting, andconsistent with the Wndings of Study 2, mothers’ reportsof overprotectiveness were not signiWcantly related totheir children’s level of explicit self-esteem. In addition,and also in keeping with the results of Study 2, mothers’reports of their own level of permissiveness were unre-lated to children’s level of implicit self-esteem. Further-more, mother’s reports of their own level ofpermissiveness were negatively related to children’sexplicit self-esteem. In short, the analyses of bothimplicit and explicit self-esteem based on mothers’ ownindependent reports of their parenting styles closely mir-rored the results of Study 2.

Discussion

Consistent with the Wndings of Studies 1 and 2, chil-dren who reported that their mothers were more nurtur-ing had higher implicit and explicit self-esteemcompared with children who reported their motherswere less nurturing. In addition, children who reportedthat their mothers were highly overprotective tended tohave low implicit self-esteem. These results replicatedusing the mothers’ own independent reports of their par-enting behavior. SpeciWcally, mothers who reported thatthey were more nurturing and less overprotective hadchildren with higher levels of implicit self-esteem.

Children and mothers’ reports of mothers’ permis-siveness were unrelated to children’s levels of implicitself-esteem, but were negatively associated with explicitself-esteem. This lack of a relation between permissiveparenting and implicit self-esteem may be due to the

Fig. 6. The relation between mother’s reports of permissiveness andchildren’s implicit self-esteem controlling for their explicit self-esteem(Study 3).

T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17 13

inconsistency in the messages that permissive parentssend to their children (Baumrind, 1971). For example,although permissive parents are likely to be openlywarm and caring, they may also send children the mes-sage that they do not care—because they do not botherto enforce rules or provide structure. Perhaps it is thisinconsistency in the feedback children receive thatexplains the lack of a relation between permissive par-enting and implicit self-esteem.

A limitation of Studies 1 and 2 was that people’s cur-rent beliefs and feelings about the self could tarnish theirreports of their childhood experiences with their parents.Study 3 minimized this possibility by showing that moth-ers’ reports of their parenting style were related to theiradult children’s implicit self-esteem levels. However, onemight expect that children with high self-esteem mayhave mothers who are also high in self-esteem (and thusalso show biased recall of parent–child interactions).However, we observed no correlation between mother’sand children’s implicit self-esteem, r (134) D¡.01, p D .95,and only a very small correlation for explicit self-esteem,r (152)D .17, p D .03 (see DeHart et al., 2003; who alsoobserved no correlation between children and theirmothers explicit self-esteem). Therefore, it seems unlikelythat we are observing this convergence in the associationbetween children and mothers’ reports of parenting andchildren’s implicit self-esteem because both are exhibitingbiased recall of early parent–child interactions. Nonethe-less, it is important to note that the list of traits thatmothers and their children could share is very long.Needless to say, other biasing inXuences shared by moth-ers and their children could threaten our preferred causalaccount of these Wndings. Our correlational design can-not allow us to rule out reverse causality.

General discussion

The current studies extend previous research on self-esteem by examining the potential origins of implicitself-esteem. In particular, reports of children’s earlyinteractions with their parents were related to the chil-dren’s levels of implicit self-esteem across all threestudies. In addition, Study 3 revealed that mothers’ ownindependent reports of their early interactions withtheir children were related to children’s level of traitimplicit self-esteem. SpeciWcally, our Wndings suggestthat: (a) nurturance was uniquely related to bothimplicit and explicit self-esteem, (b) overprotectivenesswas reliably related to implicit self-esteem, but was notreliably related to explicit self-esteem, and (c) permis-siveness was related to explicit, but not implicit, self-esteem. Finally, the associations between nurturanceand overprotectiveness and implicit self-esteemoccurred above and beyond similar associations involv-ing explicit self-esteem.

To our knowledge, this is the Wrst empirical evidencethat people’s early interactions with their parents arerelated to their level of implicit self-esteem as adults. Assuch, these Wndings constitute some of the Wrst theoreti-cally based, replicable evidence for the validity ofimplicit self-esteem (Bosson et al., 2000). For that matter,it is worth noting that we know of very little previousdata that address these same questions with regard toparenting and explicit self-esteem. People’s perceptionsof their interactions with their parents during childhoodare predictably related to both their implicit and theirexplicit self-esteem as young adults. These studies thusvalidate implicit self-esteem and help to distinguish itempirically from explicit self-esteem.

The current studies also document the methodologi-cal beneWts of repeatedly assessing implicit self-esteem.Apparently, the relation between parenting and implicitself-esteem was weak for the name-letter measure inStudy 2 because we only assessed name-letter likingonce in Study 2. Because implicit measures tend to besomewhat less reliable compared with explicit measures(see Kawakami and Dovidio, 2001; for a related discus-sion of measures of implicit stereotyping), assessingimplicit self-esteem multiple times is clearly the idealway to assess trait implicit self-esteem. Although earlywork in social cognition often took the position thatautomatic beliefs are cast in stone, more recent workhas emphasized the dynamic, Xexible nature of implicitbeliefs (e.g., see Dijksterhuis, 2004; Lowery, Hardin, &Sinclair, 2001). Thus, we believe that state implicit self-esteem can change based on current contextual inXu-ences (i.e., negative events, DeHart & Pelham, 2005),but we also believe that people possess a certain traitlevel of implicit self-esteem—around which their stateimplicit self-esteem Xuctuates (see Kernis et al., 1993,for a similar argument regarding explicit self-esteem).In short, due to the less reliable nature of measures ofimplicit beliefs as well as the meaningful short-termXuctuations that occur so readily for implicit self-esteem, assessing implicit self-esteem on multipleoccasions is likely the best way to assess trait implicitself-esteem. It is probably no accident that our resultsgenerally grew stronger when we assessed implicit self-esteem on more than one occasion or using more thanone implicit measure.

Although our Wndings answer several important ques-tions about the potential origins of both implicit andexplicit self-esteem, they also raise at least four ques-tions. First, we would like to argue that people’s implicitself-esteem is the outcome of the experiences they hadwith their parents while they were growing up. However,it is possible that people with higher implicit self-esteemreport more positive interactions with their parents.Although we cannot make causal claims on the basisof retrospective data, the convergence of children’sand mothers’ descriptions of mothers’ parenting style

14 T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17

provides additional support for these retrospectivereports. Nonetheless, determining the precise causal rela-tion between parenting and implicit self-esteem willrequire longitudinal research.

A second issue to consider is that the causal relationbetween implicit and explicit self-esteem may be diVer-ent than the one we depicted in our models. Forinstance, it is likely that implicit self-esteem is often aconsequence as well as a cause of explicit self-esteem.For example, it seems reasonable to assume that ifpeople repeatedly express positive explicit views aboutthemselves, over time these views may become auto-matized (Hetts et al., 1999). However, we drew thecausal arrow from implicit to explicit self-esteembecause theory suggests that implicit self-esteem devel-ops prior to explicit self-esteem (e.g., Bowlby, 1982;Koole et al., 2001). In fact, people’s implicit beliefspresumably begin to form before the development oflanguage and thus before the development of explicitbeliefs. Although we have no doubt that explicit self-esteem sometimes inXuences implicit self-esteem (seeJones et al., 2002), theory on the development ofimplicit self-esteem suggests that it is reasonable totreat implicit self-esteem as a predictor of explicit self-esteem.

A third important issue is whether name-letter pref-erences are in fact assessing people’s unconscious beliefsabout the self. Several investigators have noted that it isdiYcult to know whether measures of implicit self-esteem assess unconscious beliefs or assess consciousbeliefs in an indirect way (Fazio & Olson, 2003; Pelhamet al., 2005). Although we do not claim to have a simpleanswer to this question, we do know that the availableevidence suggests that people’s name-letter ratingsreXect their automatic beliefs about the self (Koole etal., 2001). For example, people who were asked to thinkdeliberately about their responses to the name-lettermeasure showed a disruption in name-letter biases. Inaddition, research shows that mildly threatening situa-tions appear to activate positive implicit associationsfor people high in explicit self-esteem (Dodgson &Wood, 1998; Jones et al., 2002). That is, some associa-tions may lie dormant until people experience threaten-ing situations that activate these beliefs (Bowlby, 1982;Pelham et al., 2005). Finally, recent research suggeststhat implicit beliefs are sensitive to at least some experi-ences that remain completely out of awareness(Dijksterhuis, 2004).

A fourth issue is whether these Wndings would extendto other measures of implicit self-esteem. The currentresearch relied on name-letter and birthday-numberpreferences (Bosson et al., 2000; Jones et al., 2002; Kooleet al., 2001). In fact, diVerent measures of implicit self-esteem are often weakly correlated with one another (asare diVerent measures of implicit memory, Buchner &Wippich, 2000; Perruchet & Baveux, 1989). However,

recent research has observed similar eVects on diVerentmeasures of implicit self-esteem that are typically uncor-related with one another (Baccus et al., 2004;Dijksterhuis, 2004; Pelham et al., 2005). For instance,separate research using the Implicit Association Testand the name-letter measure has linked high explicit andlow implicit self-esteem with greater defensiveness andhigher levels of narcissism (see Bosson et al., 2003, forname-letter Wndings; see Jordan et al., 2003, for IATWndings). Therefore, there is some evidence to suggest,albeit indirectly, that our results may extend to othermeasures of implicit self-esteem. However, futureresearch should extend the current Wndings to othermeasures.

Dissociation between implicit and explicit self-esteem

Our results support the construct validity of thename-letter measure of implicit self-esteem. In fact, toour knowledge these are some of the Wrst studies exam-ining the potential origins of people’s implicit beliefsabout the self. However, if we look at implicit socialbeliefs more broadly, a great deal of research suggeststhat implicit and explicit belief systems operate indepen-dently of one another (e.g., Banaji & Hardin, 1996;Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998; Hetts et al.,1999; Koole & Pelham, 2002). The Wnding that people’sperceptions of early experiences with caregivers areunique predictors of both explicit and implicit self-esteem is loosely consistent with this developing body ofresearch suggesting that implicit and explicit beliefs areoften dissociated.

Perhaps the most informative aspect of the currentwork is this Wnding: that diVerent aspects of parentingare diVerentially related to implicit and explicit self-esteem. For example, people’s perceptions of parentaloverprotectiveness were reliably related to implicit self-esteem but were not reliably related to explicit self-esteem. We suspect that this reXects changes in children’sability to make self-protective attributions as they growolder (e.g., see Wilson, Smith, Ross, & Ross, 2004).Because very young children are not as adept as theirolder counterparts at self-protection, the quality of veryearly parenting, such as being overprotective, might havea stronger impact on implicit than on explicit self-esteem. In other words, overprotectiveness may under-mine very young children’s (mostly implicit) sense ofautonomy or competence (see Gilbert & Silvera, 1996)but may be much less problematic once children are oldenough to engage in high levels of attributional correc-tion. When older children make such corrections forparental overprotectiveness they may protect theirexplicit self-esteem, but the damage to their implicit self-esteem may remain.

We think that the pattern of Wndings we observedbetween parenting and self-esteem may also be explained

T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17 15

if one assumes that early interactions with parents mat-ter more for implicit self-esteem and that later experi-ences with peers and close others matter more forexplicit self-esteem. In addition, these diVerent parentingvariables likely inXuence the types of interpersonal expe-riences children have with close others as they growolder. For example, as children with overprotective par-ents grow older, they presumably experience manydiVerent types of relationships that inXuence their self-esteem. That is, positive experiences with friends or otherfamily members during later childhood may be moreclosely related to young adults’ explicit than to theirimplicit self-esteem. Although people’s relationshipsmay change over time and may be reXected in theirexplicit belief system, people’s previously formedimplicit beliefs likely will remain intact (see also Hetts etal., 1999). Importantly, these negative implicit beliefsmay be elicited automatically and inXuence people’sbehavior (e.g., Jordan et al., 2003).

Our studies also showed that permissive parentingwas reliably related to explicit but not to implicit self-esteem. This lack of a relation for implicit self-esteemmay reXect the fact that although permissive parents arelikely to be openly warm and caring, they may also sendchildren the inconsistent message that they do notcare—because they do not bother to enforce rules orprovide structure. Alternately, the long term social prob-lems created by permissive parenting may leave theirmark more clearly on explicit self-esteem becauseexplicit self-esteem is more closely related to youngadults’ recent life experiences. Thus, the children of per-missive parents may receive increasingly negative feed-back from peers and authority Wgures as they grow olderbecause the impulsive or egocentric behaviors that weretolerated in children are no longer tolerated in adoles-cents or young adults.

Our results suggest that nurturance was uniquelyrelated to implicit as well as explicit self-esteem.Although at Wrst blush these results may seem inconsis-tent with models of dual attitudes that suggest thatimplicit and explicit beliefs develop from distinct experi-ences, we believe they are consistent with these models.First, our results are consistent with attachment theory,which suggests that people’s conscious and unconsciousworking models are based upon the same types of expe-riences with primary caretakers. Second, it is plausiblethat diVerent aspects of the same parenting style mayhave diVerential eVects on implicit and explicit self-esteem. SpeciWcally, parents who are nurturing mayinXuence their children’s implicit self-esteem throughnon-verbal channels, and their explicit self-esteemthrough verbal channels. Finally, unlike overprotective-ness and permissiveness, nurturance is likely to be expe-rienced as unambiguously positive by children of allages. Further, people who experience warm, positiverelationships with parents growing up may also translate

these experiences into positive relationships with friends,romantic partners, and others during later childhoodand early adulthood. Therefore, the children of nurtur-ing parents are likely to develop positive implicit as wellas explicit associations to the self.

The implicit sociometer

Are people’s implicit beliefs about the self related totheir well-being? Recent research suggests that implicitself-esteem is linked to a number of important physicaland emotional outcomes. For instance, consistent withresearch on explicit self-esteem (Brown & McGill,1989), people with low implicit self-esteem reportedmore negative health symptoms in response to positiveevents compared with people with high implicit self-esteem (Shimizu & Pelham, 2004). These eVects ofimplicit self-esteem on health were independent of con-ceptually identical eVects involving explicit self-esteem.In addition, having high implicit self-esteem seems tobuVer people from negative consequences associatedwith doing poorly (Dijksterhuis, 2004; Greenwald &Farnham, 2000), self-concept threats (Jones et al., 2002;Spalding & Hardin, 1999), unrealistic optimism (Bos-son et al., 2003), and negative daily experiences(DeHart & Pelham, 2005). Finally, assessing bothimplicit and explicit self-esteem can help identify peo-ple with secure high self-esteem versus people withdefensive or fragile high self-esteem (Bosson et al.,2003; Jordan et al., 2003).

The present studies are some of the Wrst to link peo-ple’s perceptions of early childhood experiences withimplicit self-esteem. A greater understanding of the con-ditions under which implicit self-esteem is formed willenhance our understanding of self-esteem and self-regu-lation. A great deal of additional work will be necessarybefore researchers know exactly how our experienceswith close others leave their mark on our implicit self-evaluations. For example, future research shouldexamine other parenting variables that may inXuence therelation between implicit and explicit self-esteem, such asparenting variables that have been linked to increasednarcissism and defensiveness (Jordan et al., 2003). None-theless, the present studies suggest that the time is ripefor examining both the origins and consequences ofimplicit self-esteem. If we wish to develop a better under-standing of self-esteem, it appears that we must begin totake a closer look at the unconscious. Researchers haveonly begun to scratch the surface of implicit self-esteem,and much more presumably lies beneath.

References

Baccus, J. R., Baldwin, M. W., & Packer, D. J. (2004). Increasingimplicit self-esteem through classical conditioning. PsychologicalScience, 15, 498–502.

16 T. DeHart et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 1–17

Banaji, M. R., & Hardin, C. D. (1996). Automatic stereotyping. Psycho-logical Science, 7, 136–141.

Bardone, A. M., Vohs, K. D., Abramson, L. Y., Heatherton, T. F., &Joiner, T. E., Jr. (2000). The conXuence of perfectionism, body dis-satisfaction, and low self-esteem predicts bulimic symptoms: Clini-cal implications. Behavior-Therapy, 31, 265–280.

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachmentperspective. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships, 7, 147–178.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Develop-mental Psychology Monographs, 4(1, Pt. 2), 1–103.

Baumrind, D. (1983). Rejoinder to Lewis’s reinterpretation of parentalWrm control eVects: Are authoritative families really harmonious?.Psychological Bulletin, 94, 132–142.

Bosson, J. K., Brown, R. P., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Swann, W. B. (2003).Self-enhancement tendencies among people with high explicit self-esteem: The moderating role of implicit self-esteem. Self and Iden-tity, 2, 169–187.

Bosson, J. K., Swann, W. B., Jr., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2000). Stalkingthe perfect measure of implicit self-esteem: The blind men and theelephant revisited?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,79, 631–643.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss (Volume 1: Attachment). Lon-don: Hogarth Press.

Brown, J. D., & McGill, K. L. (1989). The cost of good fortune: Whenpositive life events produce negative health consequences. Journalof Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1103–1110.

Buchner, A., & Wippich, W. (2000). On the reliability of implicitand explicit memory measures. Cognitive Psychology, 40, 227–259.

Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. M., Lavallee, L. F.,& Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, per-sonality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 70, 141–156.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York:Schocken.

Crocker, J., & Major, B. (1989). Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review, 96, 608–630.

DeHart, T., Murray, S. L., Pelham, B. W., & Rose, P. (2003). The regu-lation of dependency in parent-child relationships. Journal ofExperimental Social Psychology, 39, 59–67.

DeHart, T., & Pelham, B. W. (accepted contingent on minor revisions).Fluctuations in state implicit self-esteem in response to daily nega-tive events. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Dijksterhuis, A. (2004). I like myself but I don’t know why: Enhancingimplicit self-esteem by subliminal evaluative conditioning. Journalof Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 345–355.

Dodgson, P. G., & Wood, J. V. (1998). Self-esteem and the cognitiveaccessibility of strengths and weaknesses after failure. Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology, 75, 178–197.

Epstein, S. (1994). Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamicunconscious. American Psychologist, 49, 709–724.

Fazio, R. H., & Olson, M. A. (2003). Implicit measures in social cogni-tion research: Their meaning and use. Annual Review of Psychology,54, 297–327.

Gilbert, D. T., & Silvera, D. H. (1996). Overhelping. Journal of Person-ality and Social Psychology, 70, 678–690.

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition:Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102,4–27.

Greenwald, A. G., & Farnham, S. D. (2000). Using the implicit associa-tion test to measure self-esteem and self-concept. Journal of Person-ality and Social Psychology, 79, 1022–1038.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measur-ing individual diVerences in implicit cognition: The implicit associa-tion test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1464–1480.

Harris, J. R. (1995). Where is the child’s environment. A group sociali-zation theory of development. Psychological Review, 102, 458–489.

Harter, S. (1993). Causes and consequences of low self-esteem in chil-dren and adolescents. In R. Baumeister (Ed.), Self-esteem: The puz-zle of low self-regard. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Hetts, J. J., & Pelham, B. W. (2001). A case for the nonconscious self-concept. In G. Moskowitz (Ed.), Cognitive social psychology: ThePrinceton symposium on the legacy and future of social cognition (pp.105–123). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hetts, J. J., & Pelham, B. W. (2003). The ghosts of Christmas past:ReXected appraisals and the perils of near Christmas birthdays, man-uscript in preparation.

Hetts, J. J., Sakuma, M., & Pelham, B. W. (1999). Two roads to positiveregard: Implicit and explicit self-evaluation and culture. Journal ofExperimental Social Psychology, 1–48.