Vit D Rehab AJPMR

-

Upload

atid-amanda -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Vit D Rehab AJPMR

Authors:Kelly Myriah Heath, MDElie Paul Elovic, MD

Affiliations:From the Department of PhysicalMedicine and Rehabilitation,University of Medicine and Dentistryof New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey(KMH, EPE); and the Kessler MedicalRehabilitation Research & EducationCorporation, West Orange, NewJersey (EPE).

Correspondence:All correspondence and requests forreprints should be addressed to Dr.Kelly Heath, University of Medicineand Denistry of New Jersey, Dept ofPM & R, Newark, NJ 07103.

0894-9115/06/8511-0916/0American Journal of PhysicalMedicine & RehabilitationCopyright © 2006 by LippincottWilliams & Wilkins

DOI: 10.1097/01.phm.0000242622.23195.61

Vitamin D DeficiencyImplications in the Rehabilitation Setting

ABSTRACT

Heath KM, Elovic EP: Vitamin D deficiency: implications in the rehabilitationsetting. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2006;85:916–923.

Objective: Vitamin D deficiency, which can result from inadequate sunexposure, dietary intake, or problems with absorption, is rarely docu-mented in the rehabilitation literature. Most likely, it is rarely thought of bythe rehabilitation profession. This is problematic because vitamin D defi-ciency can present as musculoskeletal pain, which is commonly seen inboth outpatient clinics and inpatient rehabilitation units. The populationswith the greatest risk include the homebound elderly, people with pig-mented skin, people with cultural and social avoidance of the sun, peoplewho live in wintertime in climates above and below latitudes of 35degrees, and people with gastrointestinal malabsorption.

Design: The review was done using PubMed, Ovid, and MDConsultusing the search terms pain, chronic pain, musculoskeletal pain, vitamin Ddeficiency, and osetomalacia. The search revealed 107 articles and wasnarrowed down to 51 articles that focused on vitamin D deficiency and itsmusculoskeletal manifestations.

Results: A direct correlation was noted between vitamin D deficiencyand musculoskeletal pain. At-risk populations are not acquiring enoughvitamin D through sun exposure, and the current recommended dailyallowances from dietary sources including supplements are too low tocompensate for this lack of sun exposure. Treatment of vitamin D defi-ciency produced an increase in muscle strength and a marked decreasein back and lower-limb pain within 6 mos.

Conclusion: Vitamin D deficiency should be included in the differentialdiagnosis in the evaluation of musculoskeletal pain complaints in therehabilitation setting, and treatment of any identified deficiency should beconsidered a potentially important component of the treatment regimen.

Key Words: Vitamin D Deficiency, Musculoskeletal Pain, Osteomalacia, Rehabilitation

916 Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. ● Vol. 85, No. 11

REVIEW & ANALYSIS

Musculoskeletal

According to the literature, the incidence ofvitamin D deficiency in the general population is25% in the United States and more than 40% in theelderly population.1,2 What is less commonlyknown, but widely reported in the literature, is thatvitamin D deficiency can initially present as mus-culoskeletal pain, a condition that is seen all toooften by rehabilitation professionals in both outpa-tient clinics and inpatient rehabilitation units.3–10

Numerous case studies have shown drastic im-provements in musculoskeletal symptoms includ-ing back pain when normalizing vitamin D lev-els.4,8,11 Because the rehabilitation professional islikely to encounter patients with vitamin D defi-ciency, it is essential to understand the mechanismof deficiency, the population affected, and the po-tential treatments.

Normally, an adequate supply of vitamin D isobtained from exposure to the sun, with even min-imal sun exposure providing 90–100% of the re-quired vitamin D.12 Vitamin D deficiency is a two-fold problem. The first component is that when sunexposure is limited, dietary intake of vitamin Doften falls below the recommended daily allowance(RDA) because vitamin D–rich sources such as eeland cod liver oil are not mainstays in many cul-tures’ diets. The second component is that thecurrent RDA does not assure vitamin D sufficiency.Gloth13 found that 32% of nursing home patientsremained deficient, even when consuming morethan 400 IU of vitamin D per day.

The populations that are most at risk are thosethat have decreased sun exposure. This includesthe homebound elderly, people with highly pig-mented skin, people who live in wintertime inclimates above and below latitudes of 35 degrees,and those whose cultural and societal beliefs limitsun exposure.14–22 Another group at risk for vita-min D deficiency is those who have a malabsorp-tion syndrome such as Crohn’s disease or gastricstapling. In these cases, vitamin D deficiency iscaused by a decrease in absorption in the smallintestine.23

There are numerous signs and symptoms thatresult from vitamin D deficiency. They includeproximal muscle weakness, back pain, and muscleand bone pain. Treating this deficiency resulted inclinical improvement,4,7,8,10,24 with studies show-ing marked increases in strength5,8,11 and patientsbecoming pain free within 6 mos of treatment withvitamin D.3,4 The risk of toxicity resulting from vi-tamin D replacement therapy is very low.25 This fa-vorable risk/benefit ratio, coupled with the ubiquity ofcomplaints of weakness and pain in the rehabilitationpopulation, make it incumbent on the rehabilitationphysician to be knowledgeable about the diagnosisand treatment of this condition.

METHODSThe articles for review were selected through

searches in PubMed, Ovid, and MDConsult usingthe terms pain, chronic pain, musculoskeletal pain,vitamin D deficiency, and osetomalacia. The searchrevealed 107 articles, which were narrowed downto 62 relevant articles. Articles rejected from thesearch were on other manifestations of vitamin Ddeficiency, review articles on osteomalacia andrickets, or in a language other than English. Theabstracts of the 15 articles that were not in Englishwere reviewed. Although nine of these were perti-nent, they added no new information to the discus-sion and were therefore not included. After reviewof the articles, 51 were included in this reviewpaper. The remaining 11 articles were excludedbecause they were either review articles or on man-ifestations of osteomalacia not pertaining to mus-culoskeletal pain.

The Mechanism of Vitamin D Absorptionand Activation

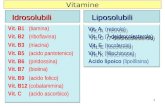

Vitamin D can be absorbed either through thedermis from sunlight or through enteral means viafood or vitamin supplements. Once absorbed by thebody, vitamin D must first be metabolized by boththe liver and the kidney before it reaches its finaluseable form of calcitriol. The ultraviolet B wave-lengths between 290 and 315 nm are the mostimportant when vitamin D is absorbed through thedermis. In the epidermis, precursor 7-dehydrocho-lesterol is activated and forms previtamin D3. Pre-vitamin D3 is then transported to the liver throughthe bloodstream and hydroxylated into 25 dehy-droxyvitamin D. It is then transported to the kidneyand hydroxylated again to 1, 25 dihydroxyvitaminD, otherwise known as calcitriol. In this form, itperforms its well-known function of calcium ho-meostasis. When ingested, vitamin D comes in twoforms, vitamin D2 and vitamin D3. Both forms arefat-soluble vitamins and are absorbed in the smallintestine. Then, the vitamin is transported to theliver and enters the same pathway of hydroxylationas sunlight sources.12 Of the oral sources, vitaminD3 has been found to yield 70% higher serum levelsthan vitamin D2 (Fig. 1).26

Daily IntakeThe Institute of Medicine17 defines the RDA for

vitamin intake to maintain vitamin D sufficiency inthe United States, and last revised the RDA in 1997.The current recommendations suggest that peopleget 5 �g (200 IU) of vitamin D from infancy to age50. For those aged 50–70, it is recommended thatintake be increased to 10 �g (400 IU), and thoseover 70 should take 15 �g (600 IU).17,27 To assesssufficiency, a serum vitamin D level is obtained.

November 2006 Vitamin D Deficiency 917

The most reliable method of determining serumvitamin D is the radioimmunoassay.28 Referencevalues for sufficiency and levels of deficiency havebeen defined in the literature, with clinical osteo-malacia defined as a serum 25 OH vitamin D �25nmol/liter, or 5 ng/ml.21,23,29 Because parathyroidhormone changes have been shown to occur atlevels of vitamin D at less than 40–50 nmol/liter,many studies use 30–40 nmol/liter, or �20 ng/ml,as the cutoff for vitamin D deficiency.7,16,21,30,31

To meet the required amount of vitamin D,one must gain adequate sun exposure or eat avitamin D–rich diet. Sun exposure has shown aprotective effect in many studies,13,14,21,32 and15–30 min of exposure can provide 90–100% of theRDA of vitamin D.12 The amount of sun exposurethat causes minimal redness of the head and hands,roughly 6% of total body surface area, will yield600–1000 IU of vitamin D.33 There is minimal riskof vitamin D intoxication resulting from overexpo-sure because ultraviolet B rays are turned into theinactive metabolites lumisterol and tachysterol,which do not circulate in the bloodstream.26 Evi-dence of sunlight’s protective effect was demon-strated by a large global study by Lips et al.,34 whofound that postmenopausal women farther fromthe equator had higher deficiency levels than thoseclose to the equator. The most striking result wasthat no women in Singapore (latitude: 1 degree)were deficient. Toss et al.35 demonstrated that ar-tificial sunlight may be an effective modality inmaintaining vitamin D levels in sun-deprived peo-ple. They demonstrated that homebound elderlywho were exposed to artificial ultraviolet radiation

once a week for 3 mins maintained their vitamin Dlevels.

Dietary sources of vitamin D include fish liveroils, the flesh of fatty fish, eggs obtained from hensthat have been fortified with vitamin D, and forti-fied milk and cereal.17 Zittermann26 reported that a100-g edible portion of either eel, salmon, or codliver oil would satisfy the RDA for vitamin intakefor all ages. However, the more commonly con-sumed foods such as eggs, butter, and milk all givefar less than 100 IU.27 Many populations worldwidedo not get enough dietary vitamin D because theirdiet contains few vitamin D–rich foods and thesupplemented foods are not sufficient. A study of417 women ages 20–80 in rural Iowa showed thatintake of vitamin D from food sources ranged from70 to 175 IU. Furthermore, this study showed thatthere was a significant correlation between sunexposure and serum vitamin D levels, but a similarrelationship was not found between food intake andserum levels.36 Many people erroneously believethat drinking milk will meet their vitamin D re-quirement, but research has shown that milkdrinkers have deficiency rates that are similar tothose of non–milk drinkers.20,21

It has also been shown that taking the RDA ofvitamin D from a multivitamin was not protectivefor the populations at risk. Despite supplementa-tion with 400 IU of multivitamin, 20% of Canadianwomen aged 18–35 were deficient in the winter.21

A study in Denmark lends further support to thisidea; 60% of Muslim women with an intake aver-aging 12 �g (500 IU) of vitamin supplementationwere still deficient.19 The above studies are remark-able in that all populations were taking the RDA ofvitamin D and still remained deficient, demonstrat-ing that even patients taking vitamin D supple-ments may still be at risk.

On the other hand, various studies have shownthat an intake greater than the RDA of vitamin D ina multivitamin has protective effects. Healthywhite women with an average age of 60 remainedvitamin D sufficient on 500 IU consumed dailyduring the winter.37 Ambulatory nursing home pa-tients showed an increase in vitamin D level of162% over placebo with treatment of 800 IU ofvitamin D3.38 Numerous studies have shown excel-lent clinical improvement of deficiency on 50,000IU or more of ergocalciferol per month, with noreported adverse effects (Table 1).4,8,13 Past workhas shown that larger doses of supplementationcannot only be tolerated but are essential to pre-vent and treat vitamin D deficiency.

At-Risk PopulationsMany different populations are at risk for vita-

min D deficiency, with a lack of sunlight often theunderlying cause. As a result, there has been great

FIGURE 1 Vitamin D metabolism. Vitamin D is ab-sorbed through the skin or small intestineand transported to the liver. From there,it is hydroxylated and sent to the kidney.It is further hydroxylated and then it cir-culates throughout the body.

918 Heath and Elovic Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. ● Vol. 85, No. 11

interest in comparing serum levels at the end ofwinter vs. summer and the beginning of fall.14,20,21,37

These studies would be expected to reflect sun-light’s effect on vitamin D because a change in oralintake is unlikely to be seasonally related. In addi-tion, vitamin D absorption from sunlight is re-duced during winter because of decreased exposureand the change in the angle of the sun duringwinter.33 In tropical countries, the angle of the sunis still adequate in the winter to provide sufficientvitamin D and also to create longer days and cli-mates that are more favorable to direct sunlightexposure. Studies performed at the equator sup-port this idea, with serum vitamin D levels rangingfrom 107 to 163 nmol/liter found during winter.26

The young, healthy population across the UnitedStates was examined for seasonal differences invitamin D. These are important studies becausemedical conditions as cofounders are reduced.These studies include internal medicine residentsin Portland with a 52% decrease in winter,39

healthcare professionals in Boston with a 35% de-crease,20 and adolescents in Bangor, ME with a48% decrease.40

Skin pigmentation has also been shown to playan important role in vitamin D deficiency.7,14,22

Melanin, which is found in higher levels in peoplewith more skin pigmentation, blocks the absorp-tion of ultraviolet B rays. Goswani et al.22 found adramatic difference between pigmented and depig-mented persons. During the winter in Delhi, India,depigmented persons received one fifth the amountof sunlight as others, yet they had significantlyhigher levels of serum vitamin D. The AfricanAmerican population is at great risk because of thelarge amount of melanin in their skin. When com-paring African American women with white Amer-ican women, Harris and Dawson-Hughes14 foundthat African American women’s levels of vitamin Dwere half those of age-matched white women re-gardless of season.

Many populations have decreased sun expo-sure regardless of climate. Cultural reasons playan important role for Muslim women who re-main veiled when outside and who, as a result,are at high risk of vitamin D deficiency. VeiledArab women living in Denmark had an averagevitamin D level of 7.1 nmol/liter compared with47.1 nmol/liter for native Danish women.19 El-derly people, especially homebound or nursinghome patients, are at increased risk because theyrarely get sunlight.13,15,16,32 This is exacerbatedby the fact that the elderly have a twofold de-crease in the ability to produce previtamin D3 inthe epidermis, placing them at even greater riskto develop deficiency if they do not double theirconsumption of vitamin D.41 Gloth et al.13,15

found that 48% of homebound elderly were vita-

TAB

LE1

Vita

min

Dde

ficie

ncy

and

mus

culo

skel

etal

pain

Aut

hors

Stud

yD

esig

nT

reat

men

tVi

tam

inD

Leve

lR

espo

nse

AlFa

raj

and

AlM

utai

ri3

Cas

eW

eigh

tba

sed:

3–22

.4nm

ol/li

ter

100%

ofpa

tien

tspa

infr

eein

3m

os(b

ack

pain

)�

50kg

:50

00IU

/day

;�

50kg

:10

,000

IU/d

ayC

hapu

yet

al.3

8R

CT

800

IUof

vita

min

D3;

1.2

gof

tric

alci

umph

osph

ate

16�

11ng

/ml

Dec

reas

eoc

curr

ence

offr

actu

re;

vita

min

Din

crea

sed

162%

deTo

rren

teet

al.4

Cas

e30

,000

IUof

chol

ecal

cife

rol

intr

amus

cula

rly,

twic

epe

rm

onth

;10

0m

gof

calc

ium

oral

ly4.

5–16

.2nm

ol/li

ter

Clin

ical

reso

luti

onin

3m

os(l

ow-b

ack

pain

and

low

er-l

imb

pain

)

Gle

rup

etal

.5R

CT

10,0

00IU

ofer

goca

lcife

rol

intr

amus

cula

rly

per

wee

kfo

r1

mo,

plus

one

inje

ctio

npe

rm

onth

for

5m

os;

daily

calc

ium

,12

00m

gor

ally

and

400–

600

IUof

ergo

calc

ifero

l

6.7

�0.

6nm

ol/li

ter

Clin

ical

impr

ovem

ent

in6

mos

wit

hle

vels

incr

ease

dto

34.5

�2.

0

Glo

thet

al.6

Cas

e50

,000

IUof

ergo

calc

ifero

lpe

rw

eek

or16

00IU

ofer

goca

lcife

rol

per

day

8–20

nmol

/lite

rC

linic

alim

prov

emen

tto

reso

luti

onof

sym

ptom

s(b

ack

and

low

er-l

egpa

in)

Prab

hala

etal

.8C

ase

50,0

00IU

ofer

goca

lcife

rol

per

wee

k12

–32

nmol

/lite

rC

linic

alim

prov

emen

tin

5–8

wks

(bac

kpa

in)

Rus

sell9

Cas

e50

,000

IUof

vita

min

D2

per

day

8pg

/dl

norm

al�

10Pa

infr

eein

1m

o(e

xert

iona

lth

igh

pain

)Zi

amba

ras

and

Dag

ogo-

Jack

10

Cas

e50

,000

IUof

ergo

calc

ifero

lpe

rda

y�

5ng

/ml

norm

al�

10N

orm

aliz

ed1–

2m

os(r

iban

dba

ckpa

in)

Trea

tmen

tof

vita

min

Dde

ficie

ncy

resu

lted

inre

lief

ofm

uscu

losk

elet

alpa

inco

mpl

aint

s.R

CT,

rand

omiz

edco

ntro

lled

tria

l.

November 2006 Vitamin D Deficiency 919

min D deficient, and a surprising 32% of nursinghome patients getting the recommended 400 IUof vitamin D were still deficient. Even younghealthy people who use sunscreen may be at risk.Sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 8 caneliminate 97.5% of vitamin D absorption fromultraviolet B rays. Those who applied sunscreen1 hr before ultraviolet B ray exposure did nothave any change in vitamin D as opposed tothose who did not apply protection. Without anysunscreen, vitamin D levels rose from 1.5–25.6ng/ml, with only one minimal erythema dose.42

Because vitamin D is absorbed by the ileum,many gastrointestinal disorders can cause defi-ciency. Malabsorption syndromes such as Crohn’sdisease and celiac sprue are important causes, andgastric stapling has also been correlated with vita-min D deficiency. As these weight-reducing proce-dures are becoming more common, the overallimportance of these conditions as a source of vita-min D deficiency is increasing. Clinicians must beaware that vitamin D deficiency should be consid-ered in the differential diagnosis in these patientpopulations when they present with skeletal symp-toms. A study evaluating gastrointestinal disordersvalidates this point. All 17 subjects with gastroin-testinal disorders had serum vitamin D levels lessthan 15 ng/ml, with 14 of them having levels lessthan 10.23 A final population that is considered atrisk is those who are obese. Obesity can also causevitamin D deficiency because the fat-soluble vita-min is stored in fat tissue rather than circulating inthe bloodstream.26

Musculoskeletal ManifestationVitamin D deficiency primarily presents with

musculoskeletal complaints and is an early warn-ing of osteomalacia. Osteomalacia is a mineraliza-tion defect in the skeleton that presents as diffusebone pain, polyarthralgias, and muscle weaknessaffecting the spine, rib cage, shoulders, andhips.29,43 As more research ensues, it seems thatbone pain and weakness may manifest with mini-mal vitamin D deficiency. Because these symptomsmirror the most commonly presenting symptomsin musculoskeletal and pain clinics, a more in-depth understanding of the populations at risk willhelp in the diagnosis and treatment of these symp-toms early in their progression.

Musculoskeletal PainEvidence for the correlation between muscu-

loskeletal pain syndromes and vitamin D deficiencyis mounting. Several studies have been reported inthe literature illustrating bone pain and/or musclepain. Ninety-three percent of patients presenting toa community health clinic with nonspecific mus-culoskeletal pain were found to have vitamin D

deficiency. It is remarkable to note that of thesepatients, 100% under the age of 30 with musculo-skeletal complaints were vitamin D deficient, with55% being severely deficient.7 Gloth et al.6 pre-sented five cases of severe lower-leg and back painas well as hyperesthesia after 6 mos or more ofconfinement to home or hospital. Al Faraj and AlMutairi3 did an extensive study on Muslim patientspresenting to internal medicine and spinal clinicswith back pain. The study of more than 300 pa-tients showed that 83% of patients had a serum 25OH vitamin D less than 22.4.

Russell’s9 astute observation that muscle painis a presenting symptom is evidenced by his exten-sive case study of 45 patients with exertional thighpain who underwent biopsy and showed severe type2 atrophy. Glerup et al.5,19 found that 96% of veiledArab women presenting to a primary health clinicin Denmark were vitamin D deficient, and 88% ofthem complained of muscle pain. They also re-ported that 35% complained of proximal muscleweakness, which manifested itself in difficulty ris-ing from a chair and climbing stairs. All of thesewomen were vitamin D deficient, with serum25-OH vitamin D levels averaging 6.7 nmol/liter.

Muscle weakness has been identified as asymptom of vitamin D deficiency.5,8,11,23 In a studyon gastrointestinal-related vitamin D deficiency,94% of patients had muscle weakness as well asbone pain for an average of 20 mos before a serumvitamin D was taken. Vitamin D levels were all lessthan 15 ng/ml, and the mean was a mere 5.4ng/ml.23 In the intensive care unit, a patient whohad an extended hospitalization was found to havemuscle weakness. All studies were normal exceptfor a very low serum vitamin D level of 3.7 nmol/liter.11 This and other studies demonstrate theimportance of considering vitamin D deficiency inat-risk populations.

Mechanism of Vitamin D–RelatedMusculoskeletal Symptoms

One proposed pain mechanism is that the in-sufficient calcium phosphate levels lead to the in-ability to mineralize the expanding collagen matrixof bone. This rubbery matrix is hydrated and ex-pands, causing an outward pressure under the peri-osteal covering. This area is richly innervated bysensory pain fibers and senses the increase in pres-sure as pain.44

A proposed mechanism for the muscle weak-ness associated with vitamin D deficiency is thatcalcidiol binds to vitamin D–dependent receptorsin muscle.18,45 In vitamin D deficiency, vitaminD–dependent receptors decrease and calcidiol hasfewer potential binding sites. Notably, treatmentwith 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D, calcitriol, did notshow an increase in muscle strength.46 Therefore,

920 Heath and Elovic Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. ● Vol. 85, No. 11

it seems that calcidiol rather than calcitriol is im-portant in maintaining muscle strength. Musclebiopsy studies have further supported this pro-posed mechanism. In clinical osteomalacia, musclebiopsy shows moderate atrophy in both type I andII fibers.47 Case studies have shown severe type IImuscle atrophy in patients presenting with muscleweakness and pain.9,10 An increase in type IIa fibernumber and size was shown after treatment withvitamin D.24 The ramifications of poor musclestrength are often seen in the rehabilitation set-ting. Past studies have shown that it leads to pos-tural and balance disturbances, contributing tofalls and fractures in the elderly.38,48,49

TreatmentNumerous case studies have shown improve-

ment of lower-extremity and back pain with thetreatment of vitamin D (Table 1).3,4,6,8–10 Al Farajand Al Mutairi3 found that 100% of patients withvitamin D deficiency had complete resolution ofpain when their vitamin D levels were normalized.However, the study excluded patients with discprolapse, spinal stenosis, and degenerative disc dis-ease found on CT and MRI. Treatment with 10,000IU/wk of ergocalciferol intramuscularly and 400–600 IU/day of ergocalciferol reduced symptomswithin one and a half months.5 Gloth et al.6 pre-sented five cases of severe lower-leg and back painand hyperesthesia after 6 mos or more of confine-ment to home or hospital. The pain was resistant toanalgesics but responded to treatment with ergo-calciferol. Three studies showed that 50,000 IU/wkof ergocalcieferol improved lower-extremity andback pain and also made the patients independentwith walking.4,6,9 If adequate levels of vitamin Dare not maintained, the symptoms will return. Onepatient with leg and foot pain returned 6 mos aftersuccessful treatment with ergocalciferol with thesame symptoms. She again had low levels of serum25 OH vitamin D (30 nmol/liter). After repeat treat-ment, her pain subsided. She ultimately required1200 IU/day of ergocalciferol.6

Numerous studies have shown improvementsin muscle strength after treatment with 25 OH-vitamin D.9–11,18,45,50,51 Bischoff-Ferrari et al.30

found that in both active and nonactive adults, thegreater the vitamin D level, the better the personwas able to perform on lower-extremity functiontesting. Activities such as time required to dress,time from sitting to standing, hand grip, and legextension power have all been shown to correlatewith 25-OH vitamin D levels.24,30,45,51 This wasfurther demonstrated in the third National Healthand Nutrition Examination Survey trials, whichshowed that an increase in vitamin D serum levelsfrom 22.5 to 40 nmol/liter yielded a significantincrease in lower-extremity function, tested by

timed sit-to-stand and walking tests.18 Ziambarasand Dagogo-Jack10 reported two patients withmuscle aches and lower-extremity weakness whohad undetectable levels of vitamin D but who im-proved within 2 mos of treatment with 50,000units of ergocalciferol orally per day.

When assessing a population of long-term carepatients in Switzerland, Bischoff et al.48 found a50% reduction in the number of falls in elderlypatients treated with 400 IU of vitamin D. The samestudy found a 9% increase in knee extensorstrength and an 11% increase in the timed up-and-go test.

DISCUSSIONMusculoskeletal pain is commonly seen in the

rehabilitation setting. In the inpatient setting,many patients arrive after weeks of hospitalization.They often arrive in poor nutritional status, rarelyhaving taken vitamin D supplementation, andmany are homebound before the onset of theirillness. As was discussed earlier in this paper, theseare populations that are at high risk for vitamin Ddeficiency.11,13,15,38,45 Many of these patients alsohave nonspecific pain complaints that could, inpart, be a result of vitamin D deficiency. Rectifyingthis problem with early intervention could poten-tially improve patients’ muscle strength and mo-bility and reduce morbidity from their condi-tions.48,50 It has already been shown that improvedmuscle strength is correlated with fewer falls andfractures.38,48,49 Outpatient rehabilitation medi-cine practices should also pay particular attentionto vitamin D status when evaluating musculoskel-etal pain complaints. Many patients present to thephysiatrist after having numerous tests related totheir pain or muscle weakness. In particular, vita-min D deficiency should be considered in patientswith low-back pain but with no MRI findings, or inhealthy patients with leg pain or unexplained prox-imal weakness.

CONCLUSIONDiagnosis of vitamin D deficiency is rarely

made by clinicians in the rehabilitation environ-ment. However, it is precisely this population thatmay be at particular risk for this diagnosis. More-over, many of the signs and symptoms that arefound in this patient population could, in part, be aresult of vitamin D deficiency, and these symptomsmight be ameliorated by vitamin D replacementtherapy. It is therefore incumbent on physicians toconsider this diagnosis in this population, obtainthe appropriate diagnostic evaluations, and ensurethat appropriate replacement therapy is offered toany patient requiring it. Clinicians should be espe-cially vigilant when treating at-risk populations andshould consider screening patients who present

November 2006 Vitamin D Deficiency 921

with skeletal complaints such as nonspecific mus-cle pain, bone pain, and muscle weakness.

The rehabilitation setting is the ideal setting tostudy vitamin D deficiency. Further research isneeded to address the prevalence of vitamin Ddeficiency in the pain population, including thosethat have MRI findings such as spinal stenosis anddegenerative disc disease. The inpatient rehabilita-tion population could also be invaluable in deter-mining the effect of vitamin D deficiency on mus-cle strength, pain, and recovery from extendedhospitalization. The effect of replacement therapyin this population could also shed considerablelight on the potential functional benefit that couldresult from the proper diagnosis and treatment ofvitamin D deficiency.

REFERENCES1. Gloth FM 3rd, Tobin JD: Vitamin D deficiency in older

people. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:822–8

2. van der Wielen RP, Lowik MR, van den Berg H, et al: Serumvitamin D concentrations among elderly people in Europe.Lancet 1995;346:207–10

3. Al Faraj S, Al Mutairi K: Vitamin D deficiency and chroniclow back pain in Saudi Arabia. Spine 2003;28:177–9

4. de Torrente de la Jara G, Pecound A, Favrat B: Musculo-skeletal pain in female asylum seekers and hypovitaminosisD3. Br Med J 2004;329:156–7

5. Glerup H, Mikkelsen K, Poulsen L, et al: HypovitaminosisD myopathy without biochemical signs of osteomalacicbone involvement. Calcif Tissue Int 2000;66:419–24

6. Gloth FM, Lindsay JM, Zelesnick LB, Greenough WB: Canvitamin D deficiency produce an unusual pain syndrome.Arch Intern Med 1991;151:1662–4

7. Plotnikoff GA, Quigley JM: Prevalence of severe hypovita-minosis d in patients with persistent, nonspecific muscu-loskeletal pain. Mayo Clin Proc 2003;78:1463–70

8. Prabhala A, Garg R, Dandona P: Severe myopathy associ-ated with vitamin D deficiency in western New York. ArchIntern Med 2000;160:1199–203

9. Russell JA: Osteomalacic myopathy. Muscle Nerve 1994;17:578–80

10. Ziambaras K, Dagogo-Jack S: Reversible muscle weaknessin patients with vitamin D deficiency. West J Med 1997;167:435–8

11. Rimaniol J, Authier F, Chariot P: Muscle weakness in in-tensive care patients: initial manifestation of vitamin Ddeficiency. Intensive Care Med 1994;20:591–2

12. Holick MF: Vitamin D. A millenium perspective. J CellBiochem 2003;88:296–307

13. Gloth FM, Tobin JD, Sherman SS, Hollis BW: Is the rec-ommended daily allowance for vitamin D too low for thehomebound elderly? J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:137–41

14. Harris SS, Dawson-Hughes B: Seasonal changes inplasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations of youngAmerican black and white women. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:1232–6

15. Gloth FM, Gundberg CM, Hollis BW, Haddad JG, Tobin JD:Vitamin D deficiency in homebound elderly persons. JAMA1995;274:1682–6

16. Semba RD, Garrett E, Johnson BA, Guralnik JM, Fried LP:Vitamin D deficiency among older women with and withoutdisability. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:1529–34

17. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Mag-nesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. Institute of Medicine ofThe National Academies, 1997.

18. Nesby-O’Dell S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, et al: Hypovita-minosis D prevalence and determinants among AfricanAmerican and white women of reproductive age: third Na-tional Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Clin Nutr 2002:187–92

19. Glerup H, Mikkelsen K, Poulsen L, et al: Commonlyrecommended daily intake of vitamin D is not sufficientif sunlight exposure is limited. J Intern Med 2000;247:260–8

20. Tangpricha V, Pearce E, Chen TC, Holick MF: Vitamin Dinsufficiency among free-living healthy young adults.Am J Med 2002;112:659–62

21. Vieth R, Cole D, Hawker G, Trang H, Rubin L: Wintertimevitamin D insufficiency is common in young Canadianwomen, and their vitamin D intake does not prevent it. EurJ Clin Nutr 2001;55:1091–7

22. Goswani R, Gupta N, Goswani D, Marwaha RK, Tandon N,Kochupillai N: Prevalence and significance of low 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in healthy subjects inDelhi. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:472–5

23. Basha B, Sudhaker Rao D, Han Z-H, Parfitt AM: Osteo-malacia due to vitamin D depletion: a neglected conse-quence of intestinal malabsorption. Am J Med 2000;108:296–300

24. Sorensen O, Lund B, Saltin BL BJ, et al : Myopathy in boneloss of ageing: Improvement by treatment with 1 alpha-hydroxycholecalciferol and calcium. Clin Sci 1979;56:157–61

25. Vieth R: Vitamin D supplementatiion, 25-hydroxyvitaminD concentrations and safety. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:842–56

26. Zittermann A: Vitamin D in preventive medicine: are weignoring the evidence? Br J Nutr 2003;89:552–72

27. Meyer C: Scientists probe role of vitamin D: deficiency asignificant problem, experts say. JAMA 2004:1416–8

28. Binkley N, Kreuger D, Cowgill C, et al: Assay variationconfounds the diagnosis of hypovitaminosis D: a call forstandardization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;89:3152–7

29. Reginato A: Muscoloskeletal manifestations of osteomalaciaand rickets. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2003;17:1063–80

30. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dietrich T, Orav EJ, et al: Higher25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated withbetter lower-extremity function in both active and inactivepersons aged �60 y. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:752–8

31. Kudlacek S, Schneider, B, Peterlik M, et al: Assessment ofvitamin D and calcium status in healthy adult Austrians.Eur J Clin Invest 2003;33:323–31

32. Dhsei J, Moniz C, Close JC, Jackson SH, Allain TJ: A rationalfor vitamin D prescribing in a falls clinic population. AgeAgeing 2002;31:267–71

33. Holick MF: Vitamin D. The underappreciated D-lightfulhormone that is important for skeletal and cellular health.Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes 2002;9:87–98

34. Lips P, Duong T, Oleksik A, et al: A global study of vitaminD status and parathyroid function in postmenopausalwomen with osteoporosis: baseline data from the multipleoutcomes of raloxifene evaluation clinical trial. J Clin En-docrinol Metab 2001;86:1212–21

35. Toss G, Andersson R, Diffey BL, Fall PA, Larko O, Larsson L:Oral vitamin D and ultraviolet radiation for the preventionof vitamin D deficiency in the elderly. Acta Med Scand1982;212:157–61

36. Sowers M, Wallace R, Hollis BW, Lemke J: Parametersrelated to 25-OH-D levels in population-based study ofwomen. Am J Clin Nutr 1986;43:621–8

37. Dawson-Hughes B, Dallal GE, Krall EA, Harris SS, SokollLJ, Falconer G: Effect of vitamin D supplementation onwintertime and overall bone loss in healthy postmenopausalwomen. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:505–12

922 Heath and Elovic Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. ● Vol. 85, No. 11

38. Chapuy MC, Arlot M, Duboeuf F, et al: Vitamin D3 andcalcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. NewEngl J Med 1992;327:1637–42

39. Haney EM, Stadler D, Bliziotes MM: Vitamin D insufficiency ininternal medicine residents. Calcif Tissue Int 2005;76:11–6

40. Sullivan SS, Rosen CJ, Halteman WA, Chen TC, HolickMF: Adolescent girls in Maine are at risk for vitamin Dinsufficiency. J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105:971–4

41. MacLaughlin J, Holick MF: Aging decreases the capacity ofhuman skin to produce vitamin D3. J Clin Invest 1985;76:1536–8

42. Matsuoka L, Ide L, Wortsman J, MacLaughlin J, Holick MF:Sunscreens supress cutaneous vitamin D3 synthesis. J ClinEndocrinol Metab 1987;64:1165–8

43. Schott G, Wills M: Muscle weakness in osteomalacia. Lancet1976:626–9

44. Mascarenhas C, Mobarhan S: Hypovitainosis D-inducedpain. Nutr Rev 2004;62:354–9

45. Mowe M, Haug E, Bohmer T: Low serum calcidiol concen-

tration in older adults with reduced muscular function.J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:220–6

46. Boonan S, Lysens R, Verbeke G, et al: Relationship betweenage-associated endocrine deficiencies and muscle functionin elderly women: a cross-sectional study. Age Ageing 1998;27:449–54

47. Golding D: Muscle pain and wasting in osteomalacia. J RSoc Med 1985;78:495–6

48. Bischoff HA, Stahelin HB, Dick W, et al: Effects of vitaminD and calcium supplementation on falls: a randomizedcontrolled trial. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18:343–51

49. Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW, et al: Vitamin D status,trunk muscle strength, body sway, falls, and fracturesamong 237 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. ExpClin Endocrinol Diabetes 2001;109:87–92

50. Janssen HC, Samson MM, Verhaar HJ: Vitamin D deficiency,muscle function, and falls in elderly people. Am J Clin Nutr2002;75:611–5

51. Bischoff HA, Stahelin HB, Urscheler N, et al: Musclestrength in the elderly: its relation to vitamin D metabo-lites. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999;80:54–8

November 2006 Vitamin D Deficiency 923