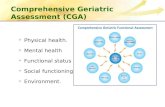

VII.3 The comprehensive geriatric assessment

Transcript of VII.3 The comprehensive geriatric assessment

S16 Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 60 (2006) Abstracts

– The task force cannot recommend any specific tool or approach aboveothers at this point and general geriatric experience should be used.

– It is worthy to note that CGA is an individualized assessment leadingto a true care program and management of older individuals. It requiresgeriatric skills. MGA and screening tools may help to detect problemsthat can possibly interfere with cancer treatment. MGA is more adaptedto population studies and clinical research programs.

13.00–14.15 Room: Jacob Pronk

Midday Session VII: Supportive care for the elderlycancer patient

VII.1 13.00–13.20Differences in supportive care for elderly cancer patients: differenceswith younger patients

G. Zulian.

Abstract not available at the time of printing.

VII.2 13.20–13.40Application of the G-CSF guidelines in elderly cancer patients

L. Repetto.

Abstract not available at the time of printing.

VII.3 13.40–14.00The comprehensive geriatric assessment

VII.4 14.00–14.15Limit-values for anaemia in elderly patients: theory and practice

14.30–15.15 Room: Jacob Pronk

Session VIII: SIOG GuidelinesModerator: Silvio Monfardini

VIII.1 14.30–14.45The use of bisphosphonates in elderly cancer patients: SIOGguidelines

R. Coleman. University of Sheffield, UK

Bone is the most common site for metastasis in cancer and is of particularclinical importance in breast and prostate cancers due to the prevalenceof these diseases. Bone metastases result in considerable morbidity andcomplex demands on health care resources. Additionally, in many patientsmetastatic bone disease is a chronic condition affecting their lives overyears rather than months. Bisphosphonates have been shown to reduceskeletal morbidity across a wide range of cancer types affecting bone.Quite appropriately, they are increasingly used alongside specific anti-cancer treatments to prevent skeletal complications. However specific rec-ommendations on their use in elderly patients is lacking. A SIOG task forcereviewed information from the literature (in PubMed) on bisphosphonatesin elderly patients with bone metastases published until December 2005.Additional pertinent data was obtained from the manufacturers.Bisphosphonates are recommended in the elderly with bone metastases toprevent skeletal-related events (SREs). Intravenous formulations are pre-ferred for the treatment of hypercalcemia. It is recognized that zoledronicacid, ibandronate and pamidronate can effectively contribute in relievingmetastatic bone pain. Creatinine clearance should be monitored in everypatient, and a less renally toxic agent should be used where evidence ofsimilar efficacy is available. The assessment and optimization of hydrationstatus is recommended. Due to the risk from osteonecrosis of the jaw,routine oral examination and treatment of dental problems by a dental teamis recommended before bisphosphonates and on a regular basis throughouttreatment.Physicians should choose the most appropriate bisphosphonate. Safetyprecautions are particularly important in elderly patients. Further researchis needed on the optimum use of bisphosphonates in elderly patients.

VIII.2 14.45–15.00SIOG guidelines: chemotherapy in elderly patients

S. Lichtman. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA

This presentation will summarize the work of the Chemotherapy Taskforceof the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. There has not been atruly systematic review of the literature with regard to patient age for overtwenty years. Much has changed since that time. The epidemiologic changeand its effect on medical oncology practice which was first recognized byYancik is now here. It is imperative that clinicians have a critical analysis ofthe available data to make important treatment decisions. The InternationalSociety of Geriatric Oncology has taken on a number of analyses ofthe literature with regard to patient age. This has included geriatricassessment, hematopoietic growth factors and surgery. It was thereforea natural extension of this work to develop a committee to systematicallyexplore the available literature with regard to chemotherapy and aging. Thisreview is to be comprehensive and hopefully will be able to developmentmeaningful guidelines and recommendations for the practicing clinicians.The committee is composed of physicians who have a recognized recordin geriatric oncology. After consultation with the committee members, itwas decided to break down the body of work by chemotherapy classesand explores issues regarding pharmacology, toxicity, drug interactionsand combinations. The committee members are:

Stuart M. Lichtman, MD Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New YorkDaniel Budman, MD North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System,

New YorkVicki Morrison, MD University of MinnesotaEtienne Chatelut, MD Institut Claudius Regaud, ToulouseHans Wildiers, MD UH Gasthuisberg, LeuvenChristopher Stiers, MD Murray Valley Private Hospital, Wodonga, Victoria,

AustraliaBrigitte Tranchand, MD Faculte Medecine Lyon-SudMatti Aapro, MD Multidisciplinary Oncology Institute, Genolier,

Switzerland

VIII.3 15.00–15.15Renal function and chemotherapy

V. Launay-Vacher. Department of Nephrology, Pitie-Salpetriere Hospital,Paris, France

Cancer patients receiving chemotherapy for their disease are at risk forrenal toxicity. Indeed, they often present with several risk factors suchas dehydration or old age that may favor anticancer drugs nephrotoxicity.Furthermore, the results of the IRMA study, a national observational studyincluding near 5000 French cancer patients from 14 oncology centers,showed that 57.4% with Cockcroft-Gault and 52.9% with aMDRD hadabnormal renal function according to the international K-DOQI definitionand stratification of renal insufficiency. Those patients with RI, togetherwith other known risk factors, are therefore at a high risk for drug-inducednephrotoxicity, and especially anticancer drugs.Anticancer drugs nephrotoxicity may result from different mechanisms.It may be induced by dehydration secondary to diarrhea or vomit-ing or by a direct toxicity to the glomerulus (adriamycin, mitomycin,pamidronate, . . . ) or to the tubule (cisplatin, methotrexate, ifosfamide,zoledronate, . . . ). In addition, hemolytic and uremic syndrome has alsobeen reported secondary to mitomycin, fluorouracil, or gemcitabine ther-apy. In those patients, identification and, whenever possible, eliminationof risk factors should be performed systematically prior to anticancertherapy. To reduce the renal risk, when two drugs with similar activitiesare available, the less nephrotoxic should be chosen. Furthermore, co-administration of other medications with potential nephrotoxicity shouldbe contra-indicated, and drugs withdrawn and/or replaced with a lessor non-nephrotoxic one. Specific procedures for preventing drug-inducednephrotoxicity should be used when necessary, eg. saline solution hy-dration during cisplatin therapy. Finally, evaluation of renal function byestimation of creatinine clearance with the Cockcroft-Gault or the aMDRDformulae should be routinely performed before and during the follow-up