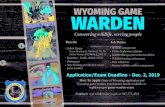

The Warden

description

Transcript of The Warden