The Mycophile 47:5 September/October 2006 - North American

Transcript of The Mycophile 47:5 September/October 2006 - North American

1 The Mycophile, September/October 2006

Volume 47:5 September ⁄ October 2006 www.namyco.org

Continued on page 11

by Andrus Voitk

Within the genus Omphalina there are two kinds ofmushrooms—those that exist as mushrooms alone andthose that exist as the fungal component of a lichen.Genetic studies of the genus showed that the lichenizedmushrooms shared DNA similarity different from therest of the genus. Therefore, Canadian mycologist ScottRedhead proposed splitting these into a separate genus,Lichenomphalia.

Lichens are very interesting organisms composed oftwo or more other organisms. One of these is always afungus and the other(s) is/are either one (or more) algaor a cyanobacterium. The fungus is by far the majorcomponent of any lichen, gives its thallus shape, andthe lichen is known by the name of the fungus. Insome instances, both component organisms existseparately as well as in their combined lichenizedform. Of the thousands of lichens, very few have abasidiomycete as the fungal partner. Only about 20species are formed with agarics (mushrooms with cap,stem and gills). It seems that in these uncommoncases, over time the basidiomycete has lost its ability tolive independently and is an obligate lichen component,found only in its lichenized form. The associated algamay not be similarly limited and may live indepen-dently as an alga or with a host of fungi as a lichen.

The method of association between fungus andalga varies. Some seemingly obligate “lichens” are

actually not true lichens, for they are loosely associatedonly, with no intermingling of components—i.e., thealga grows freely and the fungus grows freely but onlytogether with the alga. For example, Multiclavulacannot exist without its algal partner, although it is notstructurally linked to the latter. True lichenized fungihave their algal partner(s) trapped inside a film orpocket of fungal tissue. Thus it is a somewhat unbal-anced partnership: the partner that cannot exist withoutthe other encapsulates the latter and lives off itsproduce.

The poor soils of barrens, including mountaintops,are preferred habitats for many lichenized agarics.Three species of the genus Lichenomphalia wereencountered on top of Gros Morne Mountain July 4,2006. All three are associated with the same alga,

Three Lichenomphalias fromthe Top of Gros Morne Mountain

President’s Message ................................................. 2

Fungi in the News ...................................................... 3

2006 NAMA Fellowship Recipient Announced ......... 4

Book Review ............................................................... 5

Mushroom Cultivation . . . in a Glovebox! ................ 6

Recent Additions to the Mycophilic Library ............. 8

Forays and Announcements ................................... 10

Mushroom of the Month ......................................... 12

In this issue:

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

2The Mycophile, September/October 2006

The Mycophile is published bimonthlyby the North American MycologicalAssociation, 6615 Tudor Court,Gladstone, OR 97027-1032.

NAMA is a nonprofit corporation;contributions may be tax-deductible.

Web site: www.namyco.orgIsaac Forester, NAMA PresidentP.O. Box 1107North Wilkesboro, NC 28659-1107<[email protected]>

Judy Roger, Executive Secretary6615 Tudor CourtGladstone, OR 97027-1032<[email protected]><[email protected]>

Britt Bunyard, Content EditorW184 N12633 Fond du Lac AvenueGermantown, WI 53022<[email protected]>

Judith Caulfield, Production Editor927 Lansing DriveMt. Pleasant, SC 29464<[email protected]>

NAMA is a 501(c)(3) charitableorganization. Contributions to supportthe scientific and educational activi-ties of the Association are alwayswelcome and may be deductible asallowed by law. Gifts of any amountmay be made for special occasions,such as birthdays, anniversaries, andfor memorials.Special categories include

Friend of NAMA: $500–900Benefactor: $1000–4900Patron: $5000 and up

Send contributions toJudith McCandless, Treasurer330 Wildwood PlaceLouisville, KY40206-2523<[email protected]>

Moving?Please send your new address,two weeks before you move, to

Ann BornsteinNAMA Membership Secretary336 Lenox AvenueOakland, CA 94610-4675<[email protected]>

Otherwise—you may not be gettingyour newsletter for a while. Eachissue, several Mycophiles arereturned as undeliverable because ofno forwarding address on file. NAMAis charged seventy cents for eachreturned or forwarded newsletter.

The NAMA Foray in Hinton is a couple of weeks away as I write this. Imust admit that I’m looking forward to getting out of this late-July heathere in the Southeast and into those big mountains of Alberta.

This year’s foray will be different for many of us. For one of only a fewtimes since I became interested in mushrooms will I be at a NAMA foraywithout Dr. Orson Miller. He and Hope have been such regulars at theforays that you can truly say they have become fixtures. And it’s not justthe national forays but the NAMA regional and even club forays where youcould count on spending many wonderful moments with the Millers. Orsonpassed away in June after becoming ill while hunting mushrooms.

I first met Orson and Hope at just such a club foray. The year was 1987,and I had been interested in fungi for only about a year when our newlyformed Blue Ridge Mushroom Club invited Orson and Hope to join us inthe mountains of North Carolina for our first official club foray. Theyjumped at the invitation. My knowledge of mushrooms at the time mighthave taken up one page of Orson’s book—double-spaced! So here was thisignorant CPA (a term you see in the news too much these days) pickingeverything he saw, hoping for the chance for the man who “wrote the book”to help me identify the collection. I didn’t have to ask. Suddenly there heand Hope were going through my basket, taking the time to show me everylittle characteristic of each of my mushrooms. While my interest in fungihad already been sparked, they truly fanned the flames.

Continued on page 10

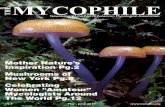

Lichen and diptera (photo courtesy J. N. Dell). See Lichenomphalias article,continued on page 11.

P R E S I D E N T ‘ S M E S S A G E

3 The Mycophile, September/October 2006

F U N G I I N T H E N E W S

Continued on page 4

By now, you’ve no doubt heard thesad news of Orson Miller’s passing.He was among the greatest NorthAmerican mycologists of all timeand will be greatly missed. Ike’swords echo the sentiments of us all.

On a happier note, a void has beenfilled in the mycological world, asour own journal, McIlvainea, hasbeen reborn. By now all members ofNAMA should have received theircopies. I greatly appreciate all thekind words of praise I’ve receivedover the past few weeks. Most ofthe praise should go to JudithCaulfield as she is the reason itlooks so good! I also am thrilled byall the requests for copies andauthor instructions from futureauthors. With such interest andenthusiasm from the mycologicalcommunity, I’m confident thatMcIlvainea is back on track and hereto stay. The next issue is scheduledfor an on-time delivery in the fall.Stay tuned!

From the British MycologicalSociety’s The Mycologist (vol. 20, part2) comes a review of AlbertHofmann’s life and involvementwith the discovery of LSD, derivedfrom a plant pathogenic funguscalled Claviceps purpurea (a.k.a.ergot). The review is actually asynopsis of an article that appearedin the International Herald Tribune tocoincide with the 100th birthday ofthe “father of LSD.”

The same issue has a reviewarticle that I highly recommend toall those somewhat puzzled by allthe discussion of DNA technologyfor the investigation of fungal diver-sity and evolution. “Sequences, theenvironment and fungi” by Mitchelland Zuccaro (20[2]: 62–74) discussesmolecular techniques ranging fromDNA extraction to PCR amplificationto DNA sequence analysis, and allthings in between: everythingyou’ve wanted to know but wereafraid to ask.

On a disappointing note, theeditorial of the same issue explainsthat at the end of the year, BMS willcease publication of The Mycologist.It will be replaced by a new journal,titled Fungal Biology Reviews. While Ilook forward to reading informativereview articles in the latter, I willgreatly miss The Mycologist. Nodoubt, regular features like “Myco-logical Dispatches” and “Profiles ofFungi” (where a different plantpathogen or other interesting gardenor woodland fungus is discussed)will be dropped. Other pertinentarticles will likely find a home inField Mycology. Of course, thisverifies the importance and timelinessof the resurrection of McIlvainea.I’m confident the members ofNAMA will welcome all mycologicalrefugees left stranded by TheMycologist’s demise.

From the Mycological Society ofAmerica’s Mycologia comes anumber of interesting articles. TheMar/Apr issue (vol. 98, no. 2) is thecurrent one; mine arrived today.

“Species diversity of polyporoidand corticioid fungi in northernhardwood forests with differingmanagement histories” by DanLindner, Hal Burdsall, and Glen R.Stanosz (98[2]: 195–217) describeshow the effects of forest manage-ment on fungal diversity wereinvestigated by sampling fruit bodiesof polyporoid and corticioid fungi inforest stands that have differentmanagement histories.

Fruit bodies were sampled in 15northern hardwood stands innorthern Wisconsin and the upperpeninsula of Michigan. Samplingwas conducted in five old-growthstands, five uneven-age stands, threeeven-age unthinned stands and twoeven-age thinned stands, during thesummers of 1996 and 1997. A totalof 255 polyporoid and corticioidmorphological species were iden-tified, 46 (≈ 18%) of which could notbe assigned to a described species.

Ten species had abundance levelsthat varied by management class.Two of these species, Cystostereummurraii and Rigidoporus crocatus,were most abundant in old growthand might be good indicators ofstands with old-growth characteris-tics. Oxyporus populinus, animportant pathogen of Acer spp., wasmost abundant in even-age stands.

As you might expect, variabilityfrom year to year suggests that morethan two years of sampling areneeded to characterize annualvariation. Changes in the diversityand species composition of thewood-inhabiting fungal communitycould have significant implicationsfor the diversity, health, and produc-tivity of forest ecosystems.

How many nuclei are present ina mushroom spore? Think it’s a trickquestion? You’ve probably alwaysjust assumed it was one. And whywould the number of nuclei perspore matter to the mushroom any-way? Thomas Horton explains(98[2]: 233–38) that the production ofeven a limited number of hetero-karyotic spores would be advanta-geous for establishing new indi-viduals after long-distance dispersal.(This strategy is analogous to self-fertilization in plants. Whileinbreeding is bad for the population,it can be beneficial to the species byestablishing new populations after along-distance dispersal event, whichcould leave an individual far awayfrom any possible mates. Think TomHanks in the movie Cast Away here.)While Suillus and Laccaria speciesare known to produce binucleate,heterokaryotic spores, this conditionis poorly studied for most ecto-mycorrhizal fungi. To begin address-ing this matter, the number of nucleiin basidiospores was recorded from142 sporocarps in 63 species and 20genera of ectomycorrhizal (EM)fungi. The mean proportion ofbinucleate basidiospores produced by

4The Mycophile, September/October 2006

Fungi in the News,cont. from page 3

sporocarps within a species rangedfrom 0.00 to 1.00 (or 100%), withmost genera within a familyshowing similar patterns. Basidio-spores from fungi in Amanita,Cortinariaceae, and Laccaria wereprimarily binucleate but were likelystill homokaryotic. Basidiosporesfrom fungi in Boletaceae, Cantha-rellus, Rhizopogonaceae, Russula-ceae, Thelephorales, and Tricholomawere primarily uninucleate, butbinucleate basidiospores wereobserved in many genera and inhigh levels in Boletus. Furtherresearch is needed to relate basidio-spore nuclear number to reproduc-tive potential in ectomycorrhizalspecies.

Back to the BMS for a look into thepages of Mycological Research.Richard Winder’s paper on “Culturalstudies of Morchella elata “ (110[5]:612–23) caught my attention. The invitro growth of Morchella elata wascharacterized with respect to theeffects of a variety of substrates,isolates, developmental status of theparental ascoma, temperature, andpH. All sorts of combinations ofdifferent carbohydrates, tempera-tures, and other factors were tested.If you’re planning to grow morels,in culture, you may want to readthis article in depth. Among all thesedata, I found it intriguing that whencalcium carbonate was used toadjust pH, optimal growth shifted topH 7.7 or above, suggesting thatwood ash and other calcium com-pounds may not only stimulategrowth in natural settings, but mayalso alter the optimal pH forproliferation of M. elata. Of course,further studies with other substratecombinations and incubation con-ditions will be necessary to fully

understand the connections betweenin vitro growth and the ecologicalbehavior of the fungus.

Taylor, et al. (110[6]: 628–32)report a new fossil fungus discovery.Well, okay, it’s not technically afungus; they determined it was mostlikely an Oomycete (based on theputative presence of oogonia andantheridia reproductive structures).

David Moore, et al. (110[6]: 626–27) sound the alarm that there is a“Crisis in teaching future genera-tions about fungi” and cite statisticsfrom colleagues around the globe,showing that schoolchildren are notbeing taught anything about fungiother than that they are decom-posers and degraders. (The fungi,not the children.) In many surveys,from several different countries,most people thought fungi andbacteria to be the same organisms.It’s time to redouble our efforts! Ithink that education of the publicshould begin at the club level. Clubmembers—get out there and spreadthe word about fungi!

From Genetics (171[1]: 101–8) comesa paper by a team of researchersthat has found that the inky capmushroom, Coprinus cinereus,exhibits remarkable photomorpho-genesis during fruiting-bodydevelopment. That is, the fungusneeds light to make mushrooms.Under proper light conditions,fruiting-body primordia proceed tothe maturation phase in whichbasidia in the pileus undergomeiosis, producing sexual spores,followed by stipe elongation andpileus expansion for efficientdispersal of the spores. And ifthere’s no light during mushroomformation? In the continuous dark-ness, the primordia do not proceed tothe maturation phase but are etio-lated: the pileus and stipe tissues atthe upper part of the primordiumremain rudimentary and the basalpart of the primordium elongates,producing “dark stipe.” In this studya gene called dst1 was discoveredand may code for a blue-lightreceptor of C. cinereus. Illuminating!

Congratulations, Bryn Dentinger!Bryn will receive $2000 and theopportunity either to contribute amanuscript for publication inMcIlvainea, or to serve as a presenterat next year’s Annual Foray.

Bryn earned a B.A. in Biologyfrom Macalester College and in 2001began working on a Ph.D. in PlantBiological Sciences with DavidMcLaughlin at the University ofMinnesota. Bryn has served as ateaching assistant in several coursesat U of M. According to one referee,“he has the ability to turn studentson to the excitement of studying thefungi” and has a “talent not only forgood science but for communicatingit to the public.”

Bryn has been involved inseveral research projects, includingecological surveys of ectomycorrhi-zal mushrooms that examinedresponses to nitrogen fertilizationand fire frequencies, ultrastructuralanalysis of subcellular characters aspart of the Assembling the FungalTree of Life project, and molecularphylogenetic analysis of clavarioidand bolete mushrooms.

Bryn’s dissertation researchfocuses on rates and causes ofspeciation in porcini mushrooms.He is the author on five publicationsand has won numerous awards,including a prestigious doctoraldissertation fellowship from the Uof M graduate school and the 2005Backus Award from the MycologicalSociety of America.

According to his referees, Bryn is“a truly exceptional student” whowill be “a major contributor tomycology, a fact already becomingevident by the many publications towhich he has made significantcontributions.”

2006 NAMA FellowshipRecipient Announced

Taylor Lockwood’s entertaining visual guide to mushroom identificationexplains all the basics with photos, illustrations, and video footage of realmushrooms. DVD ( approx. 1 hr.) includes Introduction, Into the Details, andInto the Woods. QuickTime preview at www.fungiphoto.com/treasurechest/MIT/mit.html. Reviewed in Mar/Apr ‘06 Mycophile.

Mushroom Identification Trilogy Available

5 The Mycophile, September/October 2006

The spring 2006 issue of Mushroomthe Journal has been out for a whilenow. I was relieved to read thatLeon has finished his other business(he recently earned a Ph.D. in musicfrom the University of Chicago!) andwill have that magazine “back on anormal schedule from here on out.”As always, MTJ is packed withinteresting and enlightening reads.There is a story on “HeavenlyHedgehogs” with several accom-panying recipes. The fun stories onpoisonous mushroom lore kept meriveted. Larry Evans makes a strongcase in “How to Harvest a Forest”for the preservation of forests. Itmakes financial sense, as themushroom harvests (in the West,anyway) are worth more moneythan the harvested timber. And nougly clear cuts are left as a result ofmushroom harvesting. I wasenthralled with “Mushroom-huntingwith Headhunters,” an encounterwith mushrooms in Borneo. Thenthere’s the ever-entertaining ram-blings of Maggie Rogers in “KeepingUp,” mushrooms stamps fromaround the world, and a crosswordpuzzle. If you don’t subscribe toMushroom the Journal you’re missingout on the best mycologicalmagazine out there! —Britt

B O O K R E V I E W

Fungal Disease Resistance inPlants: Biochemistry, MolecularBiology, and Genetic Engineering.Zamir K. Punja,ed. New York:Haworth, 2004. ISBN 1-56022-960-8

The diversity of fungal plant patho-gens is mind-boggling. And yet,most of the time, plants are able towithstand the onslaught of would-beinvaders. Throughout history,pathogen resistance has brokendown with noteworthy or evencatastrophic results. How plants areable to fend off fungal invasion—and how research has led to

enhanced resistance in plants—isthe topic of this highly informativebook. Plant pathology graduatestudents and professionals alike willfind Fungal Disease Resistance inPlants a very useful and illuminatingbook. Up-to-date, accurate informa-tion on recent developments in cropprotection is discussed in topicalchapters written by experts in thefield.

Fungal Disease Resistance inPlants highlights the various barriersthat plants have evolved to protectthemselves from invading fungalpathogens. These defenses includephysical barriers such as thickenedcell walls and chemical compoundsexpressed by the plant whenattacked. Still other plants haveacquired proteins that play animportant role in defense. FungalDisease Resistance in Plants discussesthese evolutionary traits and intro-duces new scientific techniques toengineer resistance in plants thathave no such protection. The editor,Zamir K. Punja, currently editor-in-chief of the Canadian Journal ofPlant Pathology, is to be congratu-lated on assembling a who’s who ofleading experts in botany, plantbreeding, and plant pathology whoshare their knowledge of the latestdevelopments in crop protection

from fungal infection to help reduceand possibly prevent new outbreaksof devastating crop epidemics causedby fungi, and fungi-like organisms.

Without intense research andscientific study, catastrophic harvestfailures due to fungal diseases willcontinue to cause food shortages,human and animal poisonings, andeconomic loss throughout the world.On-going research in this field isimportant and timely—new andemerging fungal diseases of plantscontinue to wreak devastation onforest and other economicallyimportant plants (recent examplesinclude sudden oak death, soybeanrust, and karnal bunt).

What I like most about this textis that each chapter begins with ageneral introduction to a specialsubject, followed by a compre-hensive overviews of current issuessurrounding the subject, thendiscussion of key advances and thecurrent state of knowledge for thetopic. Topics covered in the chaptersof Fungal Disease Resistance in Plantsinclude cellular expression ofresistance to fungal pathogens; thehypersensitive response and its rolein disease resistance; induced plantresistance to fungal pathogens—mechanisms and practical applica-tions; pathogenesis-related proteinsand their roles in resistance tofungal pathogens; signal trans-duction—plant networks, delivery,and response to fungal infection;and fungus genes as they relate todisease susceptibility and resistance.

With its exciting new advancesin molecular biology, biochemistry,and genetic engineering, this infor-mative book will help researchers,professors, and students furthertheir understanding of plantdefenses. —Britt A. Bunyard

[This article originally appeared inMSA’s Inoculum (57 [1]:18–19). It isreprinted here with permission.]

Fungi in the News, cont. from page 4

6The Mycophile, September/October 2006

Mushroom Cultivation . . . in a Glovebox!by James Tunney

I live in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,and am a member of the WesternPennsylvania Mushroom Club. As awalk identifier, I can safely identifyabout 120 species of mushrooms. Iam also the chairman of the Educa-tional Committee for the club.

I have had an interest in mush-rooms since I was a child. Therewas a Golden Guide mushroombook in our house when I grew up.Mostly, I just looked at the picturesin this book; I learned what aRussula was and a few other genera,as well, from having it around.

In the summer of 1996 I startedlooking for mushrooms, with aborrowed copy of the Audubon FieldGuide by Lincoff. About nine yearsago I bought a few other fieldguides, including The MushroomCultivator by Stamets. I read it andin the back of the book found a listof possible contaminants. The list atthe back of the book is somethingyou don’t want to dwell on if youare going to grow mushrooms.Thinking about that list delayed myculture work for, like, five years. Igave away my copy of TMC.

I grew a few things in themeantime with kits: shiitake andoysters. I grew blewits and shaggyparasols by adding the bases tomulch. I grew oyster by addingpieces of oysters to coffee groundsand reishi by adding pieces of it to aplum stump.

I bought another copy of TMCand started playing with agar inbaby-food jars. I use baby-food jarsfor agar mostly, as it eliminates one

place contamination can occur:pouring plates. If you don’t have aflow hood, I recommend thistechnique. Last year I gave a talk atone of the club meetings anddemonstrated how I do transfers in aglovebox using agar in baby-foodjars. I’m hoping more people in theclub do some cultivating.

What I like most about mush-room cultivation is getting a new (tome) species to fruit. (What I don’tlike is when one won’t fruit!) If I didnot care so much about failing atthis, it wouldn’t be as much fun.

Starting from either a clone orspores, and getting it to fruitSo what have I successfully culti-vated? I have grown Pleurotusostreatus on coffee grounds, card-board, tea, straw, cottonseed hulls,and logs; P. eryngii on cotton seedhulls; P. djamor on cotton seed hulls,cardboard and cocoa hulls; Panellusseratonus on sawdust and straw;Panellus stipticus on sawdust andmaple logs; Grifola frondosa on grainand agar; Shiitake on grain; Hericiumon sawdust; Agrocybe aegerita oncottonseed hulls; Lepista nuda onleaf mold outside; Hypsizygustessulatus on sawdust and buriedcardboard; Stropharia rugosoannulataon wood chips, stable bedding, andstraw. Additionally, I’ve tried to growthree times this many species.

Last winter I grew some mush-rooms I thought were going to glowin the dark. I wanted to have someglow-in-the-dark mycelium to give tomy nephews at Christmas. A friendgave me culture of Panellus stipticus

Pleurotus eryngii on cottonseed hulls.

Panellus serotinus on sawdust inpint container.

Pleurotus djamor on cardboard andcocoa hulls in a milk carton.

Pleurotus on cottonseed hulls.

Pleurotus on cotton seed hulls.

on agar. I transferred it to more agarjars after I received it. Then Iinoculated some wood shavingsmixed with bran in mason jars thathad been sterilized. None of thecultures—neither the ones on agarnor the ones on wood shavings—glowed. I told my friend about it,and he said that they were P.stipticus, which did not glow in thedark. This I could not accept,because every time I have foundone and checked it to see if itglowed, it did.

7 The Mycophile, September/October 2006

When spring came around, I hadgotten rid of some of the cultures,but I still had a few jars on woodshavings. The wood shavingscultures looked happy so I inocu-lated an 18”-long maple log 4” indiameter with some of the colonizedshavings. I cut the log halfwaythough in four places with a chain-saw and stuffed the shavings in thecuts, then wrapped duct tape aroundthe log and over the cuts andshavings to protect the myceliumfrom drying out. This was in latespring.

In the fall (five and a halfmonths later) I found some fruits onthe base of the logs. There had been

a couple of frosts, so I was sort ofsurprised to see them. The log wasin tall grass, though, so it wassomewhat protected from theweather. I posted some pictures onthe NAMA Yahoo cultivation site andsaid that since it didn’t glow, Ithought it was Panus rudis. I hadalready been told once about it notglowing in the dark; sometimes ittakes me a while to catch on. Amember of the group said that itlooked like Panellus stipticus and thatsome races of P. stipticus did notglow. Another member agreed withhim. I measured the spores; andturns out they were indeed P.stipticus.

All you need are baby-food jars anda gloveboxI have provided two pretty standardrecipes for agar media for growingmushrooms in Petri dishes (see page9). The ingredients are poured into anarrow-mouthed, closed but ventedcontainer (like a flask) and sterilizedin an autoclave for 35–45 minutes.Then you take your sterilized mediaand pour it into your Petri dishes ina sterile environment like a flowhood or a still-air environment like aglovebox.

When I first started growingmushrooms, I was looking for analternative to Petri dishes. I cameacross this technique growing inbaby-food jars. A few people hadmentioned to me that agar could bedone in jars, and when looking forthe best way to make and use aglovebox, I found a site on the webthat described using baby-food jarsto start orchids on sterile agar

media. I really like this technique. Iteliminates the need to pour plates(agar-filled Petri dishes). Pouringplates is THE step where moldspores or bacteria can get into yourmedia and contaminate it. I use thesame recipes that would be used forpouring plates. Instead of pressure-cooking a flask, I put the ingredientsinto a pot and heat till the agar isdissolved. Next I pour about 1/4 to3/8 inch of media into a jar. Ipuncture holes in the metal lids and

Continued on page 9

Blewit on straw.

Hypsizygus tessulatusfruiting on straw.

Kitty and pressure cooker.Agar jars in pressure cooker.

Stropharia rugosoannulata mycellium onchipped spruce in a box.

Wine cap with two-liter bottle.

Wine cap on wood chips and straw.

8The Mycophile, September/October 2006

Here is a helpful (I hope) index of all the books and othermedia reviewed in The Mycophile since I became editorfour years ago. The list is alphabetical by author. If youcannot find a back issue of The Mycophile with a reviewof interest to you, send me an e-mail and I will see that youget a copy of the review. My thanks to all the reviewers andespecially Steve Trudell, who has handled about 95% ofthe load! —Britt

Fungi non Delineati: Raro vel Haud Perspecte etExplorate Descripti aut Definite Picti. 26-volumeseries, individually pricedEdizioni Candusso, Via Ottone Primo 90, I-17021-Alassio-SV Italy; e-mail <[email protected]>http://edizionicandusso.itReviewed Sep/Oct 2004

Fungi in Forest Ecosystems: Systematics, Diversity,and Ecology, ed. by Cathy L. Cripps2004. Volume 89, Memoirs of the New York BotanicalGarden. NYBG Order #MEM-89; eee.nynh.othISBN 0-89327-459-3Reviewed May/June 2005

Fungi of the Antarctic: Evolution under ExtremeConditions, ed. by G. S. de Hoog.Studies in Mycology 51:1–79.2005. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht,The NetherlandsISBN 90-70351-55-2Reviewed July/August 2006

Fungi in Ecosystem Processes, by John DightonMycology Volume 172003. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York; www.dekker.comISBN 0-8247-4244-3 (hardbound)Reviewed July/August 2006

Fungi Fimicoli Italici, by Francesco Doveri2004. Associazione Micologica Bresadola, FondazioneCentro Studi Micologici dell’A.M.B., P.O. Box 296, 36100Vicenza, ItalyReviewed Sep/Oct 2004

Die Pilzflora des Ulmer Raumes (Fungus Flora of theUlm Area), by Manfred Enderle2004. Order from www.manfred-enderle.de/pilzbuch.htmISBN 3-88294-336-X; 521 ppReviewed Sep/Oct 2005

Fungal Boogie, by Larry Evans and Zoe Woodyear. Fungal Boogie, P.O. Box 7306, Missoula, MT59807Reviewed July/Aug 2005

The Secret Lives of Mushrooms: An Interactive CD-ROM, by Joel Greene2002. Toadstool Workshop, P.O. Box 1853, Flagstaff, AZ86002; www.toadstoolworkshopReviewed Nov/Dec 2003

Edible and Poisonous Mushrooms of the World, by IanR. Hall, Steven L. Stephenson, Peter K. Buchanan,Wang Yun, and Anthony L. J. Cole2003, Timber Press, Inc., Portland, ORISBN 0-88192-586-1Reviewed May/June 2004

Common Mushrooms of the Talamanca Mountains,Costa Rica: Memoirs of the New York BotanicalGarden, Volume 90Roy E. Halling and Gregory M. Mueller2005. NYBG, New York, NYISBN 0-89327-460-7; 195 ppReviewed Mar/Apr 2006

Edible Mycorrhizal Mushrooms and Their Cultivation.Proceedings of the Second International Conference onEdible Mycorrhizal Mushrooms (CD-ROM), ed. by Ian R.Hall, Wang Yun, Alessandra Zambonelli, and Eric Danell2002. New Zealand Institute for Crop and FoodResearch, Ltd., Christchurch; www.crop.cri.nz/psp/products/Emushroom.htmReviewed Nov/Dec 2003

Tanzanian Mushrooms: Edible, Harmful and OtherFungi. Norrlinia 10:1–200.Marja Härkönen, Tuomo Niemelä and LeonardMwasumbi2003. Secretary of the Botanical Museum, P.O. Box 7,University of Helsinki, Helsinki, FIN-00014 FinlandReviewed May/June 2004

The Grim Grotto (A Series of Unfortunate Events,Book 11) by Lemony Snicket, by Brett Helquist2004. HarperCollinsISBN 0-06-441014-5Reviewed Mar/Apr 2005

Fungi of Switzerland, Volume 6 (Russulaceae), byFred Kränzlin2005. Edition Mykologia LucerneISBN 3-85604-260-1 (Eng.); 317 ppReviewed July/August 2006

Morels, by Michael Kuo2005. The University of Michigan Press, Ann ArborISBN 0-472-03036-1; 206 ppReviewed May/June 2006

The Advance of the Fungi, ed. by E. C. Large, withnew introductory material by Karen-Beth Scholthof,Paul D. Peterson, and Clay S. Griffith2003, APS Press, St. Paul, MNISBN: 0-89054-308-9; 488 ppReviewed Nov/Dec 2004

Carpet Monsters and Killer Spores: A Natural Historyof Toxic Mold, by Nicholas P. Money2004, Oxford University PressISBN 0-19-517227-2Reviewed Mar/Apr 2005

Recent Additions to the Mycophilic Library

9 The Mycophile, September/October 2006

Flora Agaricina Neerlandica (Mushroom Flora of theNetherlands. Vol. 5: Agaricaceae, ed. by M. E.Noordeloos, Th. W. Kuyper, amd E. C. Vellinga2001, A. A. Balkema Publishers, RotterdamISBN 90-5410-494-5Reviewed May/June 2006

Mycorrhizas: Anatomy and Cell Biology, by R. LarryPeterson, Hughes B. Massicotte, and Lewis H. Melville2004. National Research Council of Canada, NRCResearch Press, Ottawa, Ontario K1A OR6, CanadaISBN 0-660-19087-7; 173 ppReviewed July/Aug 2005

Black Mold: Your Health and Your Home, by Richard F.Progovitz2003. The Forager Press, Cleveland, NYISBN 0-9743943-9-4; 199 ppReviewed Sep/Oct 2005

Fungal Disease Resistance in Plants: Biochemistry,Molecular Biology, and Genetic Engineering, ed. byZamir K. Punja2004. The Haworth Press, Inc., New York, NYISBN 1-56022-960-8Reviewed Sep/Oct 2006

Pathogenic Fungi: Structural Biology and Taxonomy,ed. by Gioconda San-Blas and Richard A. Calderone2004. Caister Academic Press, 32 Hewitts Lane,Wymondham, Norfolk, NR18 0JA, UKISBN 0-9542464-7-0; 371 ppReviewed Jan/Feb 2006

Pathogenic Fungi: Host Interactions and EmergingStrategies for Control, ed. by Gioconda San-Blas andRichard A. Calderone2004. Caister Academic Press, 32 Hewitts Lane,Wymondham, Norfolk, NR18 0JA, UKwww. caister.comISBN 0-9542464-8-9Reviewed Jan/Feb 2006

Fungi, by Brian Spooner and Peter Roberts2005. The New Naturalist Series; Collins, New YorkISBN 0-00-220153-4 (paper); 594 ppReviewed July/Aug 2006

A Color Guidebook to Common Rocky MountainLichens, by Larry L. St. Clair1999. The ML Bean Life Science Museum and the U.S.Forest Service, San Juan National Forest, ML Bean LifeScience Museum, 290 MLBM, Brigham YoungUniversity, Provo, Utah 84602ISBN 0-8425-2454-1; 242 ppReviewed Sep/Oct 2005

Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Savethe World, by Paul Stamets2005, Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, CAISBN 1-58008-579-2 (paper); 339 ppReviewed Mar/Apr 2006

Insect-Fungal Associations: Ecology and Evolution, ed.by Fernando E. Vega and Meredith Blackwell2005, Oxford University Press, New York, NY 10016ISBN 0-19-516652-3; 333 ppReviewed July/Aug 2005

Fungi, by Roy Watling2003, Natural World Series; Smithsonian Books (inassociation with The Natural History Museum,London), Smithsonian Institution Press, Suite 4300; 750Ninth Street NW, Washington, DC 20560-0950,www.sipress.si.eduISBN 18834-082-1Reviewed Jan/Feb 2006

MykoCD v2003.08.2, by Michael Wood14856 Saturn Dr., San Leandro, CA 94578-1349Reviewed Mar/Apr 2004

melt holes in the plastic lids about 3/16 of an inch indiameter that act as vents for air exchange for theculture. The hole is either stuffed with polyfill stuffingor taped over with tyvek. (Plastic lids should be #5plastic, which can withstand the temperatures of 15 psi.Both tyvek and polyfill can withstand the temperaturesof sterilization.) Lids are put on the jars. Jars are thenput in a pressure cooker or autoclave and pressure-cooked at 15 psi. for 15 to 20 minutes. Once the jarshave cooled, the media in these jars can be used togrow cultures by cloning from a fresh mushroom,transferring from another culture, or by adding sporesto the media. Instead of baby-food jars I now use 8-oz.jars with screw lids. I found the problem with the baby-food jars was that while the lids on baby-food jarsscrew off easily, they need to be pressed down to besealed and they don’t screw back on easily. Thispressing-down motion can cause turbulence in the airof the glovebox, which is not good.

[James can be reached at <aminitam@hotmail. com>.]

Standard agar media recipes

#1 500 ml of water10 grams of potato flakes10 grams of agar2 grams of fructose1 gram of nutrayeast

#2 500 ml of water10 grams of malt10 grams of agar

Cultivation, continued from page 7

10The Mycophile, September/October 2006

Orson will without a doubt begreatly missed at the forays,especially by those of us attendingthe Trustees’ meeting where hiscalm, level-headed approach to eachproblem always helped steer thediscussions and decisions in theright direction.

I never forgot that first meetingand how much Orson and Hopemade me feel like an old friend—something many of us can say, I’msure. I’ve had the privilege of manyforays with Orson and Hope sincethat day, and I’m sure that when-ever I’m in the woods, mushroombasket in hand, a big part of theexperience can be traced back to aremembrance of something Orsonshowed me or said. He’s not reallygone. —Ike

Ike’s message, cont. from page 2

F O R A Y S A N D A N N O U N C E M E N T S

Regional NAMA ForayWildacres, North CarolinaSeptember 28–October 1

Information and registration formcan be found in the July/Aug issueof The Mycophile or at the NAMAWeb site, www.namyco.org. Foradditional information contact AlleinStanley at <[email protected]>.

Breitenbush MushroomConferenceDetroit, OregonOctober 8–11

The 2006 Mushroom Conference atBreitenbush Hot Springs Resort incentral Oregon, near Detroit, willfeature the edible mushrooms of thePacific Northwest. Our expertmycologists will teach you how topositively identify the more deliciousmushrooms, and our expert chefsand mycophagists will teach youhow to prepare and preserve our

delectable forest and field fungi.Guided field trips, lectures, cookingand preservation, and mycopyrog-raphy demonstrations will fill thetime between sessions of soaking inthe hot waters of the naturalsprings. The practitioners of healingarts at Breitenbush can soothe yourtired muscles after hiking to collectfungi for both the identification anddinner tables. Treat yourself to aneducational, delicious, and relaxingautumnal event in the midst of theold growth forests of Oregon!

Reservations and informationcan be found on the Web site(www.breitenbush.com), or call503-854-3320 Monday throughSaturday, 9 a.m.–4 p.m. Reserva-tions are required for overnight staysand day use. Costs of the mushroomconference are $145 plus three dayslodging. Breitenbush rates vary withthe type of cabin requested. Forgeneral information by e-mail write<[email protected]>. Please

indicate your phone # in your e-mail.) For further information aboutthe conference e-mail or call PatriceBenson at <[email protected]> or 206-819-4842.

Laos in October 2006

An exciting two-week foray to exoticLaos is planned for late October! Formore information about the tour,including proposed itinerary, see theMay/June Mycophile or e-mail<[email protected]>.Please note that biological materialcannot be removed from Thailand orLaos without prior permission.

Thailand Mushroom Ecotour

For more information e-mail Dr.Edward Grand at <[email protected]>, visit the Web site(www.mushroomresearchcentre.net),or see the March/April 2006 issue ofThe Mycophile.

Hope and Orson Miller with Cathy Cripps. Photo courtesy of S. Trudell.

11 The Mycophile, September/October 2006

Coccomyxa. All are white-spored mushrooms with asimilar (omphalinoid) appearance—dimpled, wavy cap,decurrent gills, central stem. Our commonest Lichenom-phalia is L. umbellifera (a.k.a. Omphalina umbellifera,Omphalina ericetorum), found uncommonly in ourwoods and commonly on barrens. In richer habitats, itis considerably larger and lusher. Figure 1 shows somefound on the trail to Gros Morne Mountain in 2003.Figure 2, photographed on top of Gros Morne Moun-tain, shows the smaller specimen typically encounteredon the barrens. Color varies from nearly white to tan,the latter being more common on barrenland speci-mens; the stem is usually darker than the cap. Thelichen thallus is a crust of green granules. If it growson bare soil, the crust may be extensive, but in moss orother vegetation it is often not noticeable, as in theillustrations. It is found from early spring to late fall,but less commonly during the warmer part of latesummer. It is a very Canadian mushroom, with acircumpolar distribution, roughly north of the 49thparallel. Most striking of the three is L. hudsoniana withits white stem and yellow cap (Figure 3). Its foliose,green, scaly or leaf-like lichen thallus, seen at the footof the specimen on the left, is diagnostic. By conven-tion the lichen bears the name of the fungus, butbefore the connection between this thallus and L.hudsoniana was known, the thallus was known asCorsicum viride, and it can be found still under thatname in most lichen books.

A bit smaller in stature with a shorter stem is L.alpina (Figure 4). This mushroom is a deeper or moreorange yellow, superficially resembling a tiny chan-terelle in color and shape. Cap, gills, and stem are thesame color. Its lichen thallus resembles that of L.umbellifera, a green granular crust, called Botyrodiavulgaris, well seen in the photo. Both yellow Lichenom-phalias fruit in the early summer with a range con-siderably more northerly than L. umbellifera. Theclassical habitat for both is alpine, on top of barrenmountains, more so for L. alpina than L. hudsoniana.Both are also found in heaths along coastal barrens and

on barren northern coastal islands. Both are commonfinds in July along the Labrador coast, L. hudsonianasomewhat more southerly than L. alpina.

Of these three, L. umbellifera is the only one thatexists outside the specialized habitats and is thereforethe only one of the three to have made it into main-stream mushroom books. This is not because the othersare not common—no, they are quite common in thedescribed season and habitat. and because we have alot of both coastal and alpine barrens, they are verycommon mushrooms in Newfoundland and Labrador.Most people have not seen them because most peopledon’t look for small mushrooms in the summer on topof mountains or on barren coastal islands. They havenot made it to mushroom books because authors ofsame are remarkably uncommon in said habitats.

Most people consider them uncommon to rare andsomewhat exotic. Mycophiles are thrilled to encounterthese pretty mushrooms, and many are willing to bearthe cost of significant travel to do so. We are privilegedto enjoy access to them and have something worth-while to offer to mycophiles the world over. These littletreasures are worth preserving and cherishing.

Lichenomphalias, continued from page 1

For 20 years, MTJ has provided information ofvalue to those who like to hunt, name, cook, study,and photograph wild mushrooms. We’re proud ofthe job we do of reviewing books of interest tothe amateur mycologist. Our Letters column letsyou speak out and contact others to seek thatspecial book or sell that historic mushroom basket.So check us out at

www.mushroomthejournal.com

4 issues (1 yr) = $25; 12 issues (3 yrs) = $65 (save $10)

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

12The Mycophile, September/October 2006

North American Mycological Association336 Lenox AvenueOakland, CA 94610-4675

Address Service Requested

NONPROFIT ORG.U.S. POSTAGE

PAIDPERMIT NO. 1260CHAS. WV 25301

This month’s photo of oyster mushroomsfruiting from a burlap sack comes from PaulStamets’s terrific book Mycelium Running. Foran interesting twist on cultivation techniques,dig into this issue!

Mushroom of the Month