The Epidemiologic Transition Model- Accomplishments and Challenges

-

Upload

alvaro-marin -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of The Epidemiologic Transition Model- Accomplishments and Challenges

-

8/13/2019 The Epidemiologic Transition Model- Accomplishments and Challenges

1/3

The Epidemiologic Transition Model: Accomplishments and Challenges

MANNING FEINLEIB, MD, DRPH, FACE

Changes in population size and structure are determined bybasic processes that can be summarized by the demographicequation (Fig. 1). While demographers and those concernedwith population growth tend to emphasize fertility trends,and immigration policy is very much on the current politicalagenda, epidemiologists tend to concentrate their effortsstudying the factors associated with the third part of theequation.

Late in the nineteenth century, demographers, followingMalthusian principles, developed several theories to de-

scribe how populations change over long periods of time.Dudley Kirk (1) points out that,in 1929, Warren Thompsoncategorized populations on the basis of fertility and mortality(2), followed in 1934 by the first use of the term transitionby Adolphe Landry (3). But it is Frank Notestein who isgiven credit for the first full statement of the demographictransition model in 1945(4). This model was expanded byAbdel Omran in a seminal article in 1971 in which he re-named the model the epidemiologic transition model (5).

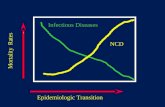

Whereas earlier demographers were concerned primarilywith changes in fertility, Omran emphasized the mortalityaspects. Omran renamed the four stages of the demogra-phers transition model for population evolution to empha-

size some epidemiologic aspects (Fig. 2): Stage 1, whichdemographers called pre-modern, he labeled the stage ofpestilence and famine characterized by high death ratesand high birth rates with low population size. Stage 2dur-banizing and industrializingdhe described as the stage of re-ceding pandemics resulting from a gradual conquest ofdisease primarily through better sanitation and nutritionand resulting in a reduction of mortality, especially childmortality, and a concomitant gradual increase in populationsize. Stage 3dmature industrialdhe called the stage of de-clining births with a peaking of the size of the population.Stage 4dpostindustrialdwas characterized as the stage of

degenerative and man-made disease with a balance betweenbirth and death rates, both at low levels, and a leveling off ofthe population size.

It should be pointed out that the model is an idealizedsummary of the stages in a populations development. Itfits fairly well the demographic changes which occurred inWestern Europe and the English-speaking countries during

the late eighteenth century through the mid-twentieth cen-tury, and there is evidence that the pattern is being followedby many developing countries, although the pace of thetransitions varies greatly.

My aim in this short essay is not to discuss the details ofthe various stages of the epidemiologic transition model butto use it as a platform to mention some of the major accom-plishments of epidemiology in the past and to highlight thechallenges and opportunities that lay ahead (Fig. 3).

I view epidemiology as the provider of the evidential

basis for public health action and for many clinical practices.Thus the accomplishments of epidemiology in preventingand controlling disease and enhancing longevity are intri-cately dependent on the implementation of its findings atthe individual patient level and through community publichealth programs.

During the pre-modern stage, epidemiology contributedlittle other than to emphasize the periodic increases in mor-tality resulting from epidemics, famine, and other hardships.But during stage 2, as epidemiologic and medical knowledgeand public health applications increased, there was a gradualdiminution of infectious diseases generally and some curtail-ment of epidemics. Infant mortality especially improved

while the birth rate remained high so that populations grad-ually increased in size.

The third stage is characterized in this model by a reduc-tion in the birth rate. The reasons for this decline are com-plex, involving many societal, cultural, and economicfactors(1), but some of the epidemiologic and public healthinfluences were the improved survival of children and, morerecently, the availability of effective birth control methods.This period also saw improvements in nutrition and greaterconcern with the health and safety of the labor force. Withboth mortality and birth rates at low levels the growth of thepopulation leveled off and the concerns of epidemiologists

and public health workers shifted to chronic diseases andtheir prevention. Many personal risk factors related to life-style and individual behaviors were identified. A greaterawareness of environmental hazards grew and many regula-tory and educational policies were instituted to reduce envi-ronmental risks. Omran dubbed this stage the age ofdegenerative and man-made disease (5).

I would like to propose that we should now recognizea fifth stage in the epidemiologic model. This stage is char-acterized by birth rates below the population replacementlevel, an aging population with many more elderly depen-dent on a diminishing working population for their

Address correspondence to: Dr. Manning Feinleib, Johns HopkinsBloomberg School of Public Health, Epidemiology, Bloomberg E6153,Baltimore, MD. Tel: (410) 614-0146. Fax: (410) 955-0863. E-mail:[email protected].

2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1047-2797/08/$see front matter360 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10010 doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.08.004

mailto:[email protected]:[email protected] -

8/13/2019 The Epidemiologic Transition Model- Accomplishments and Challenges

2/3

economic and healthcare support, and, medically, greaterdependence on advanced technological devices and proce-dures to diagnose and treat diseases. This newly proposedstage we may call that of aging and shrinking populations.Many developed nations are already well into this phase.

What can we look forward to in the twenty-first century?

I think that there is still much that epidemiologists and pub-lic health workers in general can contribute at every stage ofthe epidemiologic transition model (seeFig. 3,lower panel).

In those societies that are at the pre-modern stage, wheredisease levels are high and famine is still a constant threat,epidemiologists can contribute to improving health byadvocating for basic improvements in sanitation and widerimmunization of children. They can also urge the develop-ment of basic epidemiologic toolsdvital registration andhealth statistics systems. Lacking accurate and completedata, it is difficult to assess the magnitude of health prob-lems, identify vulnerable subgroups, or measure the impactof public health programs.

Although great progress has been made in controlling in-fectious diseases in virtually all developed nations, emerginginfections, exemplified by HIV/AIDS, are a major problemin urbanizing/industrializing areas. Combating these

diseases will engage epidemiologists for decades to come.There is also the opportunity for epidemiologists to guideplanners and policy makers in developing countries inavoiding some of the hazards that urbanized communitieshave experienced. Better city planning, avoidance of over-crowding, provision of adequate transportation systems,

safe work environments, and modern educational systemswould go far to preventing future health problems as wellas many other social ills.

In mature industrial societies epidemiologists will devotemost of their efforts to preventing chronic diseases, educat-ing the public about healthy lifestyles, assessing early detec-tion and treatment programs, and improving theavailability, accessibility, and utilization of health services.These activities will merge with evolving progress in thefields of genomics, immunology, and diagnostics to betterdefine and detect illnesses. Epidemiologists will broadentheir involvement in social diseases, including substance

abuse and violence. They will also be major players in under-standing and ameliorating subgroup disparities in health andlongevity.

As we enter the fifth stage of the epidemiologic transitionmodel, epidemiologists will become increasingly involvedwith the health conditions that prevail at both extremesof the age distribution. Providing for the health needs of old-er patients will encumber greater proportions of communi-ties resources. Broader aspects of the well-being of olderpersons, especially the oldest old, will necessitateexpanded information about their physical, social, economic,and psychologic environments, not only their biologic,physiologic, and cognitive functioning. As the birth rates

decrease, children will become increasingly precious. Therewill be ever-increasing devotion to the salubrious develop-ment of children in all aspects, including physical, mental,emotional, and societal.

Epidemiologic Transition Model

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Time

CDR CBR Population

1 2 3 4 5 1 - Pestilence and

famine

2 - Receding

pandemics

3 - Declining

births

4 - Degenerative

& man-madedisease

5 - Aging and

shrinking

population

FIGURE 2. The epidemiologic transition model.

The Demographic Equation

Family ValuesFecundity

Gender roles

Contraception

EconomicsPolitics

Persecution

Opportunities

Disease

Famine

War

Senescence

Suicide

Risky behavior

P = Births Migration - Deaths

FIGURE 1. The demographic equation.

Feinleib AEP Vol. 18, No. 11EPIDEMIOLOGIC TRANSITION November 2008: 865867

866

-

8/13/2019 The Epidemiologic Transition Model- Accomplishments and Challenges

3/3

This has been a wide view of the accomplishments ofepidemiology and some of the challenges we willencounter in coming decades. The American Collegeof Epidemiology has played an important role in encour-aging and recognizing epidemiologists in their endeavorsand will continue to provide leadership, guidance, andstimulation in the future. It has been a pleasure andan honor for me personally to have been a participantin these activities.

REFERENCES

1. Kirk D. Demographic transition theory. Population Studies. 1996;50:361387.

2. Thompson WS. Population. Am J Sociol. 1929;34:959975.

3. Landry A. La revolution demographique. Paris; 1934.

4. Notestein F. Population: the long view. In: Schultz T, ed. Food for theworld. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.; 1945. p. 3657.

5. Omran AR. The epidemiologic transition: a theory of the epidemiology ofpopulation change. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1971;49:509538.

Impact of Epidemiology

Elder care

physical,social,

economic,

psychologic,

Child

development

Genomics,

Education tomodify life

styles,

substance

abuse,

violence

Prevention

of chronicdiseases,

Health

services

HIV/AIDS,

emerginginfections,

city

planning

Sanitation,

immunization,Vital

registration &

Health

Statistics

Future

Injuries,

technological

fixes

Smoking &

other

riskfactors,

environmen-tal risks

Birth

control,

occupa-

tionalhealth,

nutrition

Reduced

infectious

diseases &

infantmortality

NilPast

54Post

Industrial

3Mature

industrial

2Urbanizing/

Industriali-

zing

1Pre-

modern

Stage

FIGURE 3. Impact of epidemiology.

AEP Vol. 18, No. 11 FeinleibNovember 2008: 865867 EPIDEMIOLOGIC TRANSITION

867