Student-centered integrated anatomy resource sessions at Alfaisal University

-

Upload

michele-cowan -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

1

Transcript of Student-centered integrated anatomy resource sessions at Alfaisal University

SHORT COMMUNICATION

Student-Centered Integrated Anatomy Resource Sessions atAlfaisal University

Michele Cowan, Nasir Nisar Arain, Tawfic Samer Abu Assale, Abdulelah Hassan Assi, Raed Alwai Albar,Paul K. Ganguly*

Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh,Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Alfaisal University is a new medical school in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia thatmatriculates eligible students directly from high school and requires them to participate ina hybrid problem-based learning (PBL) curriculum. PBL is a well-established student-cen-tered approach, and the authors have sought to examine if a student-centered, integratedapproach to learn human structures leads to positive perceptions of learning outcomes. Tenstudents were divided into four groups to rotate through wet and dry laboratory stations(integrated resource sessions, IRSs) that engaged them in imaging techniques, embryology,histology, gross anatomy (dissections and prosections), surface anatomy, and self-directedlearning questions. All IRSs were primarily directed by students. During two second-semes-ter organ system blocks, forty students responded to a structured questionnaire designed topoll students’ perceptions of changes in their knowledge, skills, and attitudes as a result ofIRS. The majority (60%) of students felt that the student-centered approach to learningenhanced their medical knowledge. Most students also felt that the IRS approach was ad-vantageous for formulating clear learning objectives (55%) and in preparing for examina-tions (65%). Despite their positive feelings toward IRS, students did not view this learningapproach as an adequate replacement for the knowledge gained from lectures and text-books. Students’ performance on objective structured practical examinations improved sig-nificantly for the two curricular blocks that included IRS compared with earlier non-IRSblocks. A student-centered approach to teach human structure in a hybrid PBL curriculummay enhance understanding of the basic sciences in first-year medical students. Anat Sci Educ3:272–275. © 2010 American Association of Anatomists.

Key words: student-centered approach; integrated resource session; structured question-naire; PBL curriculum; Saudi Arabia; undergraduate anatomy

INTRODUCTION

In 2009, the College of Medicine at Alfaisal University in Riyadh,Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, enrolled its first medical class of 80

students, in which approximately 30 students entered directlyfrom high school. As at 60 percent of other medical schools inthe Gulf region, curriculum planners at Alfaisal Universityadopted a hybrid problem-based learning (PBL) curriculum(Khalid, 2008). The focus of this integrated program is primarilyon PBL sessions, supported by lectures, large-group discussions,tutorials, and e-learning (Azer, 2001; Whelan et al., 2002). ThePBL model is an instructional strategy in which students collabo-ratively solve problems presented to them through a variety ofclinical cases. PBL requires qualified facilitators, makes heavy useof small group sessions, and depends on students’ abilities forself-directed learning. The medical curriculum at Alfaisal Univer-sity was recently revised to include unique integrated resourcesessions (IRSs), including gross anatomy laboratory stations thatemphasize critical thinking, problem solving, and peer teaching.

*Correspondence to: Dr. Paul Ganguly, College of Medicine, AlfaisalUniversity, PO Box 50927, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 11533.E-mail: [email protected]

Received 24 May 2010; Revised 6 July 2010; Accepted 21 July 2010.

Published online 2 September 2010 in Wiley Online Library(wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI 10.1002/ase.176

© 2010 American Association of Anatomists

Anat Sci Educ 3:272–275 (2010) SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2010 Anatomical Sciences Education

Learning needs in anatomy education relate to both thestructure and function of the human body, and the curricu-lum at Alfaisal University addresses these dual objectivesthrough weekly small-group sessions during which studentsdiscuss clinical PBL cases and related anatomy content. Anat-omy is taught by region or organ system during a course thatspans three semesters (approximately seven hours/week) andincludes faculty instruction and self-directed study. Explora-tion of regional, systemic, and clinical anatomy follows fromtriggers incorporated into each week’s PBL cases. Significantefforts have been made to integrate gross anatomy with otherbasic and clinical sciences. For example, when students aredealing with the theme of limb movement, the PBL casesinvolve shoulder dislocation and myasthenia gravis, and atthe same time, gross anatomy of the shoulder joint and rota-tor cuff muscles is emphasized. Students’ learning objectivesat this point in the curriculum also relate to osteology andembryology of the upper limb; imaging of the shoulder jointwith X-ray, computed tomography, and magnetic resonancetechniques; histology of muscles and motor units; and nerveconduction, action potentials, and excitation-contraction cou-pling.

Scheduled curricular time is divided between faculty lec-tures (two to three hours/week) and anatomy laboratorysessions (four hours/week). Lectures are meant to explaindifficult concepts and consolidate them around broad themes.Laboratory sessions are geared toward allowing students todevelop their own learning objectives and work in a varietyof media to meet them. In favor of more active learning, theanatomy faculty designed the IRS to be a student-centered,hands-on experience, engaging students in problem-solvingexercises, that provides a wide range of modalities for learn-ing, and create opportunities for peer teaching (Moust et al.,1989; Ganguly et al., 2003). Thematic stations were devel-oped that include embryology, histology, radiologic imaging,surface anatomy, observation of prosected specimens, andpractical examination through cadaveric dissection. All IRSactivities are primarily directed by students and accompaniedby self-directed learning questions. The student-centered pro-cess of IRS is intended to facilitate development of knowl-edge, skills, and attitudes that can become the foundation ofclinical competence and professionalism. Students’ under-standing of anatomy is tested by several methods, includingmultiple choice questions, short answer questions, and objec-tive structured practical examinations (OSPE). Continuousassessment of tutorials and end-of-unit examinations providethe basis for evaluating students’ capabilities in the areas ofgroup dynamics, thought processing, and critical appraisal.

Evaluating students’ perception of IRS and their effectivenessin the learning process provides insight into the developmentof teaching modes outside the traditional didactic experience(Abu-Hijleh et al., 2004, 2005; Drake, 2007). We administereda nine-question survey to first-year medical students in anattempt to evaluate the effects of IRS on learning, recognizingthat no single method yet exists for effectively testing all threeaspects—knowledge, skills, and attitudes—of learning (Nendazand Tekian, 1999). Multiple choice questions generally assessknowledge; short answer questions, problem solving skills; andOSPE, clinical skills and attitudes (Chakravarty et al., 2005).The best measure of any teaching-learning outcome is continu-ous assessment, and our IRSs allow this type of ongoing feed-back for students and faculty.

This article discusses the unique structure of IRS as partof the gross anatomy course at Alfaisal University, their align-

ment with the hybrid PBL curriculum, and their implicationsfor medical students’ education and performance.

METHODS

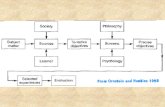

IRSs were introduced to the medical curriculum at AlfaisalUniversity in the 2009/2010 academic year. Sessions in thedry and wet laboratories occurred simultaneously, twice perweek in two-hour sessions. At the start of each week, aboutten students met with the instructor in the wet laboratory fora one-hour tutorial, reviewing and dissecting all the materialrelated to that week’s theme. These ten students then metwith the rest of their classmates in small groups for 15–30minutes of peer teaching through prosection examination andcadaveric dissection. In the dry laboratory, students workedin small groups to review diagrams, self-directed questions,anatomical models, plastinated specimens, histologic slides,radiologic images, and videos. An instructor was present atthe beginning of each session to clarify objectives, but themajority of scheduled time was for student-led and -centeredlearning. Figure 1 shows the organization of structured wetand dry laboratory sessions.

To examine the efficacy of our system, first-year studentswere asked to complete a structured questionnaire regardingtheir perception of the effect of IRS on their learning in themusculoskeletal and cardiovascular blocks. Although we rec-ognize the importance of faculty evaluations and students’ ex-amination scores in measuring learning outcomes, students’perception of outcomes may also be valuable and may relateto survey responses (Ganguly et al., 2003). Questionnaireswere administered voluntarily using an on-line course man-agement system, the modular object-oriented dynamic learn-ing environment (Moodle), version 1.8.10 (Moodle Pty Ltd.,Perth, Australia), and answers were collected anonymously.

Figure 1.

Organization of integrated resource sessions (IRSs). Groups A and B reviewcadaveric specimens in the wet laboratory, whereas Groups C and D work atdry laboratory stations. Groups spend 30 minutes at each station, which arepredominantly student-centered, and then rotate.

Anatomical Sciences Education SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2010 273

RESULTS

Forty students completed the Moodle survey during the mus-culoskeletal block (response rate was 56% as eight studentsdropped the course) and again during the cardiovascularblock (response rate was 55%). Most students reportedspending at least two hours per week in the laboratories(34.8% reported two to four hours/week; 43.5%, four to sixhours/week). Only 4.3 percent of students reported time inlaboratories of less than two hours per week, which suggeststhat IRSs may have been attractive learning opportunities forstudents. Survey responses indicate that first-year studentsgenerally perceived increases in their knowledge base andlevel of comfort with self-directed learning (Table 1).

The majority (60%) of students felt that the student-centeredapproach to learning enhanced their medical education. Moststudents also felt that the IRS approach was advantageous forformulating clear learning objectives (55%) and in preparing forexaminations (65%). Despite their positive feelings toward IRS,students did not view this learning approach as an adequatereplacement for the knowledge gained from lectures and text-books. From the faculty perspective, IRS allowed a large num-ber of students to access quality information in a student-cen-tered, small-group, theme-based laboratory setting.

Student responses to the second administration of the survey,during the cardiovascular block, were similar to the findingsdescribed above. Again the majority of students felt that IRSswere beneficial: There was a perception of increased knowledgeand more integrated objectives within each curricular theme.

We used results of OSPE before and after the introductionof IRS to evaluate their efficacy separate from the studentopinion surveys. Chakravarty and co-workers (2005) providea detailed description of OSPE. As IRSs were first introducedin the second semester of the most recent academic year (Feb-ruary 2010), the same students in the aforementioned muscu-loskeletal and cardiovascular blocks were not exposed to IRS

during their first semester. Statistically significant increaseswere observed in average OSPE scores for both the musculo-skeletal (12.6% 6 0.8, P < 0.05) and cardiovascular (17.2%6 1.0, P < 0.05) blocks (IRS) compared with the averageOSPE score in the first semester (non-IRS).

DISCUSSION

It has long been recognized that intensive efforts are needed toreform medical education worldwide to meet the future healthcare needs of the population (Parsell and Bligh, 1995; Drakeand Pawlina, 2010). Monitoring and fine-tuning curricula, ei-ther in whole or by parts, are essential for medical educationimprovement (Drake and Pawlina, 2010). While learning is themain goal in our hybrib PBL curiculum, the assessment of anynew intervention must take into account knowledge, skills,and attitudes and how these are modified. One of the majorchallenges of planning and developing a medical curriculum isto envision innovative teaching strategies that align with thehybrid PBL model (Whelan et al., 2002). Additionally, effi-ciency of time and space must be factored into curricular planswhose overarching goals are to provide the most relevant andhighest quality information in a small-group, peer-taught, stu-dent-centered approach (Ganguly et al., 2003; Chan andGanguly, 2008). At Alfaisal University, these challenges weremet through the development of IRS.

Alfaisal University was founded in 2008 in the Kingdomof Saudi Arabia. Students can apply to the medical programimmediately after completing high school, so our educationalefforts have needed to recognize that the target audienceincludes very novice adult learners. IRSs are one manifesta-tion of our attempts to integrate basic and clinical sciences,with limited resources and in a timely manner, while stillmaintaining the small group and peer teaching models of thehybrid PBL curriculum. Fundamental comprehension of basicsciences is a critical building block for the future development

Table 1.

Integrated Anatomy Resource Sessions Survey Results (Expressed as Percentages of n 5 40 Student Respondents)

Assessment statements Agree(%)

Disagree(%)

Neutral(%)

1 I have learned a lot from the laboratory sessions 67.5 17.5 15.0

2 The laboratory sessions provided me with a greater amount

of information than the textbook and PowerPoint presentations

27.0 47.0 26.0

3 The laboratory sessions made understanding the integrated course easier 55.0 20.0 25.0

4 The laboratory sessions made it easier to understand the theories and

concepts

65.0 13.0 22.0

5 I was more motivated to learn in the laboratory sessions 55.0 20.0 25.0

6 The laboratory sessions provided me with the opportunity to identifymy strengths and weaknesses

55.0 23.0 22.0

7 Attending the laboratory sessions made me feel more prepared

for the examination

65.0 20.0 15.0

8 The laboratory sessions helped me apply what I had learned

in other situations

60.0 17.5 22.5

9 The laboratory sessions helped me formulate clear learning objectives 55.0 28.0 17.0

274

of medical students. The concept-oriented, multidisciplinary,problem-based approach to learn has been shown to be effec-tive for first-year medical students studying human structure(El-Moamly, 2008; Wang et al., 2010).

Although not strictly adherent to the PBL format, ourIRSs echo the student-centered philosophy of that pedagogi-cal model. The IRSs at Alfaisal University have many novelattributes:

1. Sessions are highly adaptable, tailored to the needs of nov-ice adult learners.

2. Students are simultaneously exposed to gross anatomythrough cadaveric dissection and a wide variety of othermodalities in the concurrent wet and dry laboratory ses-sions.

3. Students define their own learning objectives and pursuethem after clarification from instructors.

4. Students are supervised in teaching peers from their owncadaveric dissections, generating interest in dissection andconfidence in teaching.

5. High level of activity, engagement and enthusiasm duringinteractive sessions prevents students with borderline aca-demic performance (minimum passing score 60%) frombeing lost to shy, silent nonparticipation.

Our study faces certain limitations. First, the relativelylow survey response rate of �56% may suggest that the sam-ple is not representative of the entire medical school class atAlfaisal University and may not be generalizable to other stu-dent populations. Second, our nine-item questionnaire is nei-ther focused exclusively on nor addresses all aspects of stu-dents’ learning. Next, knowledge, skills, and attitudes are notnumerical entities easily quantified and analyzed, but we havetried to capture students’ perceptions of changes in theselearning parameters as a result of a novel educational inter-vention, namely IRS. Finally, IRSs are a new teaching strategyat a young medical school. Though our findings suggest thatIRSs are beneficial to students’ learning, data so far only existfor two curricular blocks.

CONCLUSIONS

In the PBL approach to medical education, students areexpected to apply processes of reasoning rather than purelymemorize facts (Ganguly et al., 2003; Chakravarty et al.,2005; Chan and Ganguly, 2008; Kassirer, 2010). This appli-cation of process facilitates development of a more organized,conceptual knowledge base, with emphasis on body systemsand disease categories. IRSs are in line with the PBL con-struct of small group, student-centered, integrated approachesto develop long-lasting understanding of medicine. In thefuture, the role of IRS may expand to include preparing andassessing students’ clinical competence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions ofProfessor Khaled Al-Kattan, Dean of the College of Medicine,in helping to develop a state-of-the art anatomy resource cen-ter at Alfaisal University. The active participation of themany members of the anatomy teaching faculty in developingIRS activities is also greatly appreciated.

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

MICHELE M. COWAN, M.Sc., is an instructor in theDepartment of Anatomy and Cell Biology at the College ofMedicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Ara-bia. She teaches anatomy to medical students during the first,second, and third semesters of the medical curriculum.

NASIR NISAR ARAIN is a second-semester medical stu-dent at the College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh,Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He was involved in data collectionand analysis for this study.

TAWFIC SAMER ABU ASSALE is a second-semester med-ical student at the College of Medicine, Alfaisal University,Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He was involved in datacollection and analysis for this study.

ABDULELAH HASSAN ASSI is a second-semester medicalstudent at the College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Ri-yadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He was involved in data col-lection and analysis for this study.

RAED ALWAI ALBAR is a second-semester medical stu-dent at the College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh,Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He was involved in data collectionand analysis for this study.

PAUL K. GANGULY, M.B.B.S., M.D., F.A.C.A., is a pro-fessor of anatomy in the Department of Anatomy and CellBiology at the College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Ri-yadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He is an instructor and direc-tor of the anatomy course and head of the college assessmentcommittee. One of his research interests is medical education.

LITERATURE CITEDAbu-Hijleh MF, Kassab S, Al-Shboul Q, Ganguly PK. 2004. Evaluation of theteaching strategy of cardiovascular system in a problem-based curriculum: Stu-dent perception. Adv Physiol Edu 28:59–63.

Abu-Hijleh MF, Chakravarty M, Al-Shboul Q, Latif NA, Osman M, Bandara-nayake R, Ganguly PK. 2005. Structured problem-related anatomy demonstra-tion: Making order of random teaching events. Teach Learn Med 17:68–72.

Azer SA. 2001. Problem-based learning. A critical review of its educationalobjectives and the rationale for its use. Saudi Med J 22:299–305.

Chakravarty M, Latif NA, Abu-Hijleh MF, Osman M, Dharap AS, GangulyPK. 2005. Assessment of anatomy in a problem-based medical curriculum. ClinAnat 18:131–136.

Chan LK, Ganguly PK. 2008. Evaluation of small-group teaching in humangross anatomy in a Caribbean medical school. Anat Sci Educ 1:19–22.

Drake RL. 2007. A unique, innovative and clinically oriented approach toanatomy education. Acad Med 82:475–478.

Drake RL, Pawlina W. 2010. An interesting partnership: Undergraduate (col-lege) and medical education. Anat Sci Educ 3:73–76.

El-Moamly AA. 2008. Problem-based learning benefits for basic sciences edu-cation. Anat Sci Educ 1:189–190.

Ganguly PK, Chakrabarty M, Latif NA, Osman M, Abu-Hijleh M. 2003.Teaching of anatomy in a problem-based curriculum at the Arabian Gulf Uni-versity: The new face of the museum. Clin Anat 16:256–261.

Kassirer JP. 2010. Teaching clinical reasoning: Case-based and coached. AcadMed 85:1118–1124.

Khalid BA. 2008. The current status of medical education in the Gulf Coopera-tion Council countries. Ann Saudi Med 28:83–88.

Moodle. 2010. Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment.Course management system. Version 1.8.10. Moodle Pty Ltd., Perth, Australia.URL: http://moodle.com [accessed 6 July 2010].

Moust JHC, de Volder ML, Nuy HJP. 1989. Peer teaching and higher level cog-nitive learning outcomes in problem-based learning. High Educ 18:737–742.

Nendaz MR, Tekian A. 1999. Assessment in problem-based learning medicalschools: A literature review. Teach Learn Med 11:232–243.

Parsell GJ, Bligh J. 1995. The changing context of undergraduate medical edu-cation. Postgrad Med J 71:397–403.

Wang J, Zhang W, Qin L, Zhao J, Zhang S, Gu J, Zhou C. 2010. Problem-based learning in regional anatomy education at Peking University. Anat SciEduc 3:121–126.

Whelan AM, Mansour S, Farmer P. 2002. Outcomes-based integrated hybridPBL curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ 66:302–311.

Anatomical Sciences Education SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2010 275