St Pete's booklet

-

Upload

strelka-institute-for-media-architecture-and-design -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

1

description

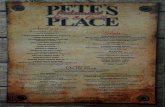

Transcript of St Pete's booklet

Director

Rem Koolhaas

Anastassia SmirnovaNikita Tokarev

Tamara MuradovaAnna ShevchenkoOlga KhokhlovaYefim Freidine Dasha ParamonovaDenis LeontievKuba SnopekShi Yang

Shi Yang

Anatoly Kovalev

Supervisors

Students

Designer

Editor

Essay on Boris Yeltsin presidential library 3

What could be said about the renovation? 10Essay on communication museum 14Declaration of St-Petersburg and its suburbs as world heritage 18

The lecture by Kira Dolinina 30Conservation strategy of the stationary system 33

Two faces 41Historic city transformed 50

Program

March 7, Monday

March 8, Tuesday

March 5, Saturday

March 6, Sunday

photo by Shi Yang

11.00 – 12.30 The Grand Museums of St. Petersburg: Imperial ambitions, territorial expansion, and the trial by contemporary art lecture by Kira Dolinina (art-critic, Kommersant correspondent, professor at the European University of St. Petersburg);

12.00 - 14.30 Excursion The State of the Hermitage: transformations, mutations, reconstructions by Elena Entsina and Anna Trofimova (department of the antiquities)

16.30 – 18.00 Preservation Strategy 2006 in St. Petersburg: How it works today? lecture by N. Kirikov, preservation expert, former member of the Strategy work-ing team (tbc)

10.00– 11.30 Visit to the Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library in the former parliament building by Carlo Rossi. Large-scale reconstruction project in the very centre of St. Petersburg as a representation of the new grand style.

12.00 – 13.30 Lecture Genius Loci: New St. Petersburg declaration for Unesco by Alexander Margolis, member of the St. Petersburg governmental committee for historic preservation; Q&A

15. 00 - 22.00 Field work. 4 teams of students are going to film four architectural offices of their choice actively building in St.Petersburg. The outcome of this shooting session will be a short movie composed of four 3-minute stories (free format) that show architects’ ambitions in the historical cities.

12.00-1.30 Excursion to the General Staff Building Highly acclaimed by the Russian professional press, the project by Yaveyn architects will be assessed by the members of the Hermitage museum staff.

14.00 – 15.30 Excursion to the Museum of Communica-tion in the former Besborodko palace “Adjusting the 18th century palace to the needs of the contemporary museum of technology”. Winner of the prize “Changing museum in the changing world. 2009”, considered to be one of the most successful preservation projects in Russia.

Library

“ This library will become the unique intel-lectual resource that represents more fully the history of the Russian State at every historical stage, including the present day”------ Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev, President of Russia.

The main purpose of establishing the Presi-dential Library is to create a single informa-tion field which would promote: respect for the country’s history and Russian Statehood and popularization of the government institu-tions activity and strengthening their link with the public.

Library includes electronic reading rooms (contain more than 60 thousand of storage units, electronic copies of old manuscripts, maps, photo albums, newspapers, mono-graphs and scientific works), multimedia center and exhibition halls.

Building

Located in the historical building of Synod, architectural monument of the late Neoclas-sical

In 1829-36, the total reconstruction of the old Senate building and neighbouring house of Kusovnikova was executed following architectural plans drawn up by architect K.I. Rossi, after that the buildings were occupied by the Governmental Senate (building No.1) and Holy Synod (building No.3).

Sculptors N.S. and S.S. Pimenov, V.I. Demut-Malinovsky, P.P. Sokolov, N.A. Tokarev, I. Leppe, N.A. Ustinov, P.V. Svintsov took part in the creation of the sculptural decor; paint-ers B. Medici, F. Richter, A.I. Solovyev, V.G. Shiryaev and others executed the interior decoration.

2

Essay on Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library

We arrived early in the morning. Saint Petersburg greeted us with its extremely dark atmosphere, its normal state. Deserted streets and imperial architecture created a feeling of a mysterious expectation. As we crossed the streets one by one, each time a wonderful perspective was opening to us. I was thinking that Saint-Petersburg was mostly a city of the past, because it perfectly preserved its intan-gible and elusive charm.

I remember how many years ago, when I was preparing to apply to the Moscow Architectural School, I got to know the name of the architect Carlo Rossi for the first time. In our huge family library, which occupied half of the room, I found one book which instantly attracted my attention. It was an archi-tectural album dedicated to the works of the famous Russian architect: Carlo Rossi. He had a great influence on the image of Saint Petersburg, as a city of imperial and sublime architecture. Endless squares, monumentality and grandeur—this is how I had imagined the city. From this book I had got the image of the city, and only after 8 years I visited it for the first time.

By coincidence, the first place of our destination was Boris Yeltsin’s Presidential Library, opened in September 2009. It is located in the historic Synod building by Carlo Rossi, in one of the oldest and most beautiful squares of the city—Senatskaya Square. On the way to this place, we had an amazing walk through the park near the Admiralty buildings. Snow covered the alley leading to a beautiful building. It was a fantastic picture, which might be an image on a postcard.

To enter Boris Yeltsin’s Presidential Library, one needs to pass the strict security system. Inside, at the entrance hall we met a guide—a representative of the architectural firm which had carried out the restoration. That was an architect named A. Mikhailov. He looked very proud of this work. All restora-tion and construction works took one and a half year to be completed and consumed an enormous budget.

At first glance it looks ambiguous: I wonder if the idea was to recreate it in the former palace style or to substitute all the old beauty with new materials? In my personal opinion, which may be quite subjective, buildings are like people. And when talking about preservation, I perceive the total de-struction of the inner structure as a kind of murder. Artificial plaster, artificial marble, artificial reality, artificial atmosphere and artificial memory—these feelings create the interior.

An interesting fact: after the restoration, only 80 fireplaces and a few windowsills survived. Fire-places and windowsills—is that a rudiment of the past or a tribute to the past times?

Boris Yeltsin’s Library is more Russian president’s pride than a library. It is a social and cultural center, where all the president’s events are held. The building has the following structure: on the first floor there is a space for visitors, on the second, ceremonial exhibition halls. On the third, the library proper, the fourth is occupied by technical facilities. As an additional feature, it houses 20 apartments, including one suite for the president, and one for the patriarch. All restoration work was inspired by two historical styles—empire and the old Russian style. To increase the total area of the building, a decision was made to cover the inner courtyard with a glass roof and thus create an atrium. After archaeological excavations, remains from the late 18th century were found on the underground level. The architect’s main pride is the principal staircase and the restored dome, pos-sibly based on Carlo Rossi’s sketches. It was made using grisaille technique. Yet, we are not sure, if it was made on the basis of Rossi’s sketches. In this case, the value of the word “reconstruction” is jeopardized one more time.

text by Tamara Muradova

3

For me, the time patina is one of the most important things in restoration. If that fluid disappears, buildings start to look as if they have just been erected. The value of such a building, for me, reaches its nadir. I think that, during a restoration project, it is very important to leave the “traces of time”: small pieces of the past, like brick masonry, antique wooden floors, original doors and windows, not recovered parts of paintings and fretwork. All that has its authenticity and a value difficult to esti-mate. All that underlines an inspiring charm of the past. Deceptive is that restoration which removes all that dust layer—an important visual time cycle.

The restoration of the great Carlo Rossi’s historic Synod building was a big disappointment for me. Walking inside that building I had a feeling that I am at a luxury hotel, somewhere in an Asian country. It is a mix of disgust and terrifying feelings which are fatal for a young architect. I survived. But, if it is a long-term tendency, I doubt that I will.

photo by Dasha Paramonova

4

!

8

The General Staff Building is an edifice with a 580 m long bow-shaped facade, situated on Palace Square in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in front of the Winter Palace.

The building was designed by Carlo Rossi in the Empire style and built in 1819–1829. It consists of two wings, which are separated by a tripartite triumphal arch and commemorating the Russian victory over Napoleonic France in the Patriotic War of 1812. The arch links Palace Square through Bolshaya Mor-skaya St. to Nevsky Prospekt. Until the capital was transferred to Moscow in 1918, the building served as the headquarters of the General Staff (Western wing), Foreign Ministry and Finance Ministry (Eastern wing) and as the headquarters of the Leningrad Military District.

The Eastern wing was handed over to the Hermitage Museum in 1989. The Grand Hermitage program was developed for the renovation and widening of the museum complex. It proposes adding a large part of historical buildings of Palace Square to the existing museum spaces. In 2001, there was a competition for the right to carry out the reconstruction organized by World Bank. Brothers Yavein won the tender and became the project’s official architects.

The General Staff Building is a city block of complex structure with five inner courtyards. The design of the Yavein brothers is well-known—the interior courtyards are turned into a large enfilade with a roof of glass. Half of work is already done, the remaining part should be finished in 2014. According to the project, the ground level is for city use and the upper floors are for the Hermitage exposition which will consist of the Impres-sionists’ and Post-Impressionists’ art.

As for OMA, it acts as consultant to the Guggenheim-Hermitage foundation from 2001. Apart of this, Koolhaas also tends to put forward his own ideas for developing the biggest Russian museum.

What could be said about the renovation?

In the Yaveins project the huge staircase that appears to embody the way to the sublime, as if the sublime needs to be introduced through such solemn means, operates more like a cheap scenery. Here we’re faced with the main problem of the local mindset: the notion of quality with regard to its outward presentation. Quality in Russia equals opulence that is usually expressed in visual pomposity. But any attempt to reach the same quality as seen in historical environ-ment through modern technologies is doomed to failure. Carefully painted walls of the newly renovated General Staff Building remind us of European-style renovation that provides maximum commonisation of quality and thereby is in contradiction to the uniqueness of the Hermitage.

If there’s no possibility to eliminate the notion of opulence, we have to change its concept. The project of OMA, “The Hermitage-2014: Master Plan,” called for modesty and cost reduction, it proposed minor modifications (reconstruction of only two courtyards instead of five). It also suggested such futuristic ideas as giving one room to a young artist for a year or using new technologies to operate within the intricate space of the museum.

The project lost competition, since no one here understands why decrease the cost of such an ambitious project. Russians don’t think in terms of sustainability and cost reduction: it works the other way around—a show of wealth, privileges and power is synonymous with beauty. If we need to have renovation, then it ought to demonstrate pompos-ity and imperial ambitions rather than modesty and delicacy. Hence the massive staircase from which you can see nothing, the huge portals 14 meters high as if made for colossi and not for normal people, the major interior modifica-tions of the building that ignore its structure. Because of lack of expenses on real quality, the final result resembles only fake settings for a B-grade movie. The fact that the Impressionists have to be exposed in paper decorations witnesses the hidden hatred towards any modernistic movement (for example, an old lady—the museum worker whom we asked about the location of Malevich’s Black Square—was highly displeased by the question).

We have to comment that the postmodernist style is only too suitable for representing imperial ambition—the 1970s style that was forgotten in the West but suddenly brought back to life by Russian architects. While the paradigm has changed and the West is concerned with effectiveness of building industry, we still associate effectiveness with Khru-shev’s era mass construction, so we tend to return to the previous phase of pseudo-historical exuberance. We always take two steps back. We can’t be deceived by effectiveness, we know from experience—effectiveness equals shortage.

We have to notice that, although OMA lost the competition, its participation has left a significant mark—if not on material representation, then on the minds of the younger architects’ generation. The main challenge is widening our perception of ways of working with historical environment, new renovation strategies and understanding of contem-porary notion of quality, not connected to the demonstration of power but directed towards improving environmental performance. If the notion itself changes, the reality also changes, as reality always reflects our beliefs.

text by Anna Shevchenko

10

Museum of Communication

The A. S. Popov Central Museum of Communications, one of the oldest museums of science and technology in the world, is located in the historic centre of St. Peters-burg, near Isaac Square.The building of the Museum is a former palace of Prince A. Bezborodko, the Chancellor of the Russian Empire, and a wonderful monument of architecture of the 18th century by the architect Giacomo Quarenghi. The construction started in the 1780s. The palace amazed the contemporaries by its splendour—Chancellor Bezborodko was a very rich person and a connoisseur of art. Art Academy even elected him as an Honourable Fancier of Art in 1974.

After Bezborodko’s death, the collection of art was divided by his family, contrary to his last will. In 1829, the palace was bought by the Postal Department.

The Museum was founded by Carl Carlovich Luders—the head of the Telegraph Department of Russia, on the 11th of September, 1872: “…For the purpose of familiari-sation of all the telegraph workers and other interested persons with all innovations and improvements in the field of telegraphy.”Since 1945, the Museum bears the name of an outstand-ing Russian scientist and inventor, Professor Aleksandr Stepanovich Popov, who was first to demonstrate the transmission of radio signals over distance.

The building of the Museum suffered a lot during World War II. In 1974, it was closed because of the construc-tion emergency condition.The Museum’s revival in the year of the 300th an-niversary of St. Petersburg became possible due to the initiative and continuous support of the Russian Federation Ministry of Communications and Information, the Russian Fund for the History of Communications, the “Svyazinvest” company, and various sponsors.

Nowadays, archives and collections contain over 8 million items, they consist of authentic documents and objects relating to the history of the postal system, telegraph and telephone, radio and broadcasting, space communication and all modern means of telecom-munication. The Museum preserves 15,000 pieces of equipment, 50,000 archival documents, vast collections of postage stamps, including the eight-million items Rus-sian National Collection of Philately, and a specialised research library with 50,000 books and periodicals. Among the exhibited items are old travelling papers, royal decrees, the first radio set invented by A. Popov, and the first civil communication satellite “Luch-15.”

New large rooms of the reconstructed Museum building, its expositions and modern technology make it pos-sible to hold corporate and international conferences, seminars, round tables devoted to museums and other special subjects. Over the years, it can be of much inter-est for sponsors, specialists of different spheres, and general public.

In 2009, the Museum became the “Changing museum in the changing world” prize winner. The prize was awarded for the project “Pedestrian walks for the citizens along the Post Town of Saint Petersburg.”

12

Information is taken from the websiteshttp://www.rustelecom-museum.ru/ and http://www.worldwalk.info

Essay on communication museum

Have you ever been to the Polytechnic Museum in Moscow? If not, snatch an hour to visit it; in view of the Museum’s impending closure for refurbishment, this could be doubly important. You’ll see a lot of items of incomprehensible use standing in transparent cases and on pedestals, all in the hollow sounding halls of the 19th century building.

And now, imagine such kind of institution in Saint Petersburg—I’m talking about the A. S. Popov Central Museum of Communications which stands close to Isaac Cathedral. The Museum positions itself as a perfect example of combination of old and new: the 18th century palace of Chancellor Bezborodko and the brand new museum of communications. We were invited there to see a good example of adjusting an architectural monu-ment to the needs of a contemporary museum of technology.

One can’t say that this example is not good. But I left the museum with the feeling that what I had seen failed to live up to my expectations. It appeared as an eclectic analogue of Moscow Polytechnic Museum with the same transparent boxes with objects. Eclectic— because of the exhibition design style that was chosen for the latest retrofit.

The Museum’s director—L. N. Bakayutova—mentioned that, right before the reconstruction started, she re-ceived a piece of advice from Ralph Appelbaum during his seminar for museums’ directors in Saint Petersburg in 2000. Mrs. Bakayutova showed him the photos of the Museum’s building, and he said that “you’ll gain a lot if you make high-tech in an 18th century building.” This opinion was taken as a guideline, and the Saint Peters-burg design office “Dizart” was invited to make this idea come true.

Suffice it to recollect Mr. Appelbaum’s high-tech projects of that period of time—Intel Museum (Santa-Clara, CA), Liberty Science Centre (Jersey City, NJ), Newseum (Arlington, VA)—to assume that he meant something different from what one can see in the Museum of Communications now: strange, unattractive constructions placed without any connection to the palace’s environment. It’s clear that the designers wanted to play with contraposition of old and new, but in the end all parts look discretely, sometimes dowdily. What seemed “cool high-tech design” at the time, looks over-detailed and even naïve 10 years later.

One of the reasons of such a state could be a very tight schedule to which the reconstruction project had to work. The whole work—from the concept till the installation of equipment—took only 1 year and 8 months. It was an initiative timed for the celebration of the 300th anniversary of Saint Petersburg and everything was done in a rush. To give an example: the “Luch” satellite had to be put in the Modern Communications Room, but the arch was closed up so quickly that the satellite was left at the entrance atrium.

Of course, there are several great examples of well-preserved spaces which are integral part of the Museum’s everyday life. These are the Main Gala Room (500 m2) and a small room with a rare double dome. Both have an authentic décor and are used for holding events of different scale. The “Treasury”—a storeroom for the unique collection of pre-1923 postage stamps—can be named as a good example of modern intervention into a historic monument. Nevertheless, the Museum of Communications leaves a general impression of uncoordinated spaces of widely varying quality. The surviving parts of original decoration, framed by modern finishing, look like incongruous patches and don’t convey the image of former environment.

Naturally, a lot of problems are connected with poor funding—the collection of items was not renewed since 2003, the construction cracked a little due to the nearby underground works, some exhibition spaces are left unfinished. According to the director’s words, the Museum gained a Potanin Foundation grant for projecting the image of former interior décor on the walls using modern technologies. Who knows, maybe this means will make the spaces of the palace more coherent? Anyway, it will take a full revision of all exhibition rooms to make the Popov Museum of Communications a truly perfect example of the coexistence of an old shell and a modern filling.

text by Olga Khokhlova

1. Director of the world’s largest museum exhibition design firm (offices in New York, London, Beijing).2. A good example of such work, in my opinion, can be seen in Neues Museum, Berlin.

14

1

2

Alexander Margolis, Scientific information center “Memorial”, Co-chairman of Saint Peters-burg City Branch of National Historic Society of Protection of Historic Monuments and Culture. In 1990 the historical center of St. Petersburg together with the palace-garden complexes of the suburbs was entered in the World Heritage List of UNESCO as “ the unique and perfect implementation of the European idea of a regular city harmonized with the landscape on a vast territory during a period of 200 years”.

After summer of 2010 the process of renomination for Unesco list was started to establish common plan or organisation method of management such protected object. The result of re-inventory should be presented on nearest Unesco session in 2011. New application will be based not only on imperial and revolutionnary history of city, but on the Blocade during WWII and cultural background. St.Peterburg isn’t only historical city centre listed by Unesco, there are nearly 50 other sites, some of them like Avignon (France) and Vienna (Austria) include related particular monuments. Political problem of preservation in Spb consists in cross-border position of its object both in the city and region, which are different administrative subdivisions of Russia (this probably relevant for Rome and Albanian sites of Be-rat and Gjirokastra). New actualisation of state of the histori-cal part connected with recent projects of Gazprom-center, Mariinsky theatre and probable delisting of Spb from historical settlements

17

The lecture of Alexander Margolis was a significant

event related to the recently started difficult process

of re-evaluation and renomination of St. Petersburg

as a world heritage site and highlighting the exciting

field trip of the Strelka Studio—an important organi-

zation of Russian and International architectural and

media communities of the opening decades of the

21st century. The renomination of St. Petersburg

could be a perfect model example for other expert

communities in the matter of application for the

UNESCO list. The lecture was concerned both with

St. Petersburg as a heritage and the declaration of

its world value. It also covered the particularly inter-

esting and complex process of analysis and group

work in this field.

The lecture was delivered on March 6, 2011, at

the office of the international Memorial foundation,

whose work is dedicated to the problem of post-

Soviet memory of Stalin’s repressions and post-war

rehabilitations. This combination of the event, place

and participators is yet to be evaluated properly in

the future.

The process of preparation of the momentous

document started with a conflict between the exist-

ing declaration and the new requirements for it. It

began with the sudden and cheerful agreement of

a group of fifteen prominent independent experts to

work—for free and to a very tight schedule—on an

alternative declaration by order of the city adminis-

tration. The uniqueness of this declaration is that St.

Petersburg is the biggest site in the world heritage

list. It is preserved as a great example of natural

and architectural consensus and a perfect one-off

created city and its agglomeration. The commission

has to have a concordance on each item men-

tioned in the declaration: ranging from its descrip-

tion to a list of monuments. borders, buffer zones,

etc. Another problem is to gather all this information

in short time: from December 2010 to March 2011.

Details of the process of application are also very

interesting from the standpoint of the crucial role

of UNESCO in the accounting and popularizing

of the world heritage. What really significant in

St. Petersburg’s history and architecture could

be made known to the international community?

Could St. Petersburg win something as a result of

being included in the list? What would it lose if it

were excluded? All these questions were answered

during that great Alexander Margolis’s lecture at the

Memorial office during the Strelka Studio field trip.

(i) The lecture is a great example of free speech

by a highly professional lecturer with an historian’s

background, the head of prominent preservation-

ist organizations, mainly independent, an expert of

state commission for the protection of heritage, a

representative of UNESCO, ICOMOS, the co-chair-

man of St. Petersburg branch of VOOPIK. His con-

versation is a perfect representation of intellectual

and humanitarian culture of Russia of the late 1980s

and of the contemporary academic community.

The lecture’s topics ranged from discussion of

formal requirements of UNESCO to the history of

St. Petersburg listing as a site in 1990, and internal

problems of application. Margolis was also asked

about his preferences in contemporary architecture

and current preservation practice. He artistically

combined in his speech a great sense of humor

with serious facts and even displayed peaceful

reaction to seemingly provocative and silly ques-

tions, which he received before from amateurs. All

these specifics represent the masterpiece of human

creative genius, produced both by studio supervi-

sors and Mr. Margolis.

(ii) An oral representation of the declaration’s proj-

ect was made, created during endless and impor-

tant discussions of expert society, which included

historians, architects, economists and other

“Declaring St. Petersburg and Its Suburbs a World Heritage” Lecture by the historian Alexander Margolis (A draft)

text by Efim Freydin

18

1

2

3

4

scientists and specialists, highly valued in St.

Petersburg and on the international level as a

multidisciplinary group, working on the most im-

portant project of our time, correcting the mistakes

made during the 1990 listing and relevant to other

UNESCO sites as well as to the Russian ones. The

declaration is like a resolution of an internal conflict

between highly professional groups in Russia and

world wide. The consensus and process itself is a

recurrent repetition of the joint work started in 1930

(the Athens meeting), continued in the 1960s (the

Venice meeting) and then in 2007 (the St. Peters-

burg meeting). This dialogue between intellectu-

ally free, independent of the state experts is a trait

specific to Russia. Not all proposed ideas were

accepted during that process. It’s highly significant

to show that it is still unclear whether the post-revo-

lution history and architecture of the 1920s could be

considered relevant part of the world heritage—per-

haps we must not preserve unanimously everything

that somehow got listed, and international experts

are skeptical of certain proposed exponents of

culture, like the Russian absurdist writer D. Kharms

(Charms) who was considered unfit for wide publi-

cation.

(iii) Exceptional impact on cultural tradition is pro-

duced by the fact of collaboration—rather than the

traditional “war”—between experts and the state

commission. Another important thing is the capac-

ity to carry out the decisions prepared by UNESCO

and local experts without the consent of a ruling

party—experts and representatives of international

organizations collaborate and prepare documen-

tation for the government, and the state simply

presents it to UN. The building of this “structure

of interaction” as well as the public presentation

(during this lecture) of reasons for the inclusion/

non-inclusion of cultural items in the lists show the

event’s extraordinary significance. Margolis told us

that listing and delisting as world heritage directly

depended on two spheres—tourist exchange

through the UNESCO system and the political repu-

tation of a state with regard how it met obligations it

took upon itself.

(iv) This type of lecture, combined with discussion

and interviews, gives us another perfect example of

contemporary rhetoric which is typical both of the

preservationist community and intellectual circles.

It is like a combination of the military argot and the

pharmaceutical slang. He speaks of the city and

its relation to architecture from the standpoint of a

“doctor.” In terms of “war” he discusses the inter-

action between the state and society, real-estate

developers and other opponents. The present

situation is described by him as revenge after long

years of fighting. At the same time, he uses expres-

sions like “the parallelogram of forces,” “balance”;

Kibovsky, the head of “Moskomnasledie” used the

same wording, but with different shades of mean-

ing.

(v) Traditional part of this lecture is the subject of

“Memorial” as an active organization defending

the memory of Stalin’s victims, the initiator of many

researches, including those of historical archives

and sites. One of the presented initiatives was to list

forests (in Russia) where people were killed as his-

torical sites. In relation to the UNESCO declaration,

Margolis mentioned the proposition to consider

in this connection the Green Belt, which was cre-

ated during the Leningrad Siege and consisted of

defenses and battlefields (a perfectly tangible site).

This connection between a public group or founda-

tion based on national or historical memory and

heritage preservation activity is typical of Russian

practice in this field. In the context of the lecture,

this link was also partly represented through the

locality.

(vi) “Memorial,” as well as Margolis himself, and

the above-mentioned old “war” between experts

(like Kirikov and others) and the government (and

experts themselves likewise) represent the cultural

layer of this lecture as a cultural heritage. This

process of preserving St. Petersburg, re-listing it in

the UN context, creating a new type of declaration

and the resolving of the ongoing conflict create

extremely interesting content descriptive of such

activity particularly important for Russian and inter-

national heritage preservation experience.

19

5

photo by Dasha Paramonova

20

1. The actual report about the lecture is presented in the form of a UNESCO declaration, following its traditional structure of description of cultural heritage: his tory of site, evaluation of criteria (i–vi). The author tried to preserve the vigor of speech present in such declarations. The nominated properties shall there fore: (i) represent a masterpiece of human creative genius; (ii) exhibit an important interchange of values, (iii) bear a unique testimony to a cultural tradition; (iv) be an outstanding example of a type of building, which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in history; (v) be an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement, which is representative of a culture (or cultures); (vi) be directly or tangibly associated with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance. (The Committee considers that this criterion should preferably be used in conjunction with other criteria).

2. Address: 23, Rubinstein Str., St. Petersburg (additional info: http://memorial-nic.org/).

3. The conflict caused both by 20 years of inactivity on the part of the Russian state in this field and by the develop ment of UNESCO documentation.

4. The All-Russian Society for the Protection of Cultural and Historic Heritage, established in 1966.

5. I must point out that St. Petersburg is not considered in the context of “intangible” heritage—cf. properties listed in Section (vi) from the world heritage list.

In the last 20 years a big economical pres-sure was put on the precious historical center of Saint Petersburg. This lead in many cases to destruction of the original atmosphere of the city. In the interview Alexei criticizes the ways how the city was developed in the last years. He totally rejects spatial policies from the nineties. He also suggests his solutions, how to deal with preservation issues in Sankt Petersburg in the future.

INTERVIEWS

“At a certain moment there rises a question: why do we need this old junk?

It’s not clear what exactly we’re saving in this building, which values are in it? So we’re preserving what is prescribed “to preserve a façade”.

Interviewer Dasha Paramonova Kuba Snopek

Interviewer Anna Shevchenko Shi Yang23

Alexey Levchukauthor of numerous projects of public and residential interiors and buildings in St. Petersburg;Holder of the Grand Prix, 1 st Prize, two 3-x interior awards in competition Moscomarchitecture /2001-2006/. He introduced the concept of 2-D and 3-D architecture during the lecture, organized by the Moscow Center of Contemporary Architecture /2008/.Education: Academy of Fine Arts, Faculty of Architecture.

Ekaterina LarinaArchitect, teacher, partner of u:lab spb group. Studied at SPb GASU and the AA. Member of the Anonymous Architects Society, Studio M, Gustafson&Porter.Daniyar YusupovStudied at SPb GASU. Member of Project Baltia 2008 editorial staff. Member of the Anonymous Architects Society, Cultural Urbanistics and u:lab spb. Teacher at the SPb GASU 2004, winner of a number of architectural competitions, participator of many project seminars. Author of articles in professional press.

24

Oskar MaderaArchitecture, public art, installations1998: Entrance to the meeting street - installation2002-2003: Peterburg of the future2005: showroom of “ROSAN” (active outdoor stuff) - interior2009: Mechanical forest - installation

Elena DeshinovaDimitri Goldenberg

25

“If we try to preserve the city and to use the originality of its environment, we should not address to it as an object. Approach as an object – that is the modernist method.”“May be I’m not a good one to answer this, because I don’t adhere any position from a certain moment…. Why? Because when we come to the plane of notions, it turns that it’s possible to do like this or like that”.

Russian architect is a “genius”. Genius and an artist. As a genius he is in constant search for his individual “genious” ways, what gives birth to “monsters”.

26

Interviewer Yefim Fredine Olga Khokhlova

Interviewer Denis Leontiev Tamara Muradova

The lecture by Kira Dolinina ‘Great’ St.Petersburg museums: imperial ambitions, territorial expansions, the test for contemporary art. The 7th of March 2011

photo by Dasha Paramonova

29

Kira Dolinina is the author of more than 400 critical articles and essays in Rus-sian and foreign publications, a participant and organizer of several international academic conferences and seminars. She is an art historian, critic and profes-sor at the department of art history of the European University at St. Petersburg (EUSP). Currently she is also working as a journalist in the Kommersant newspa-per.

Her research interest covers many areas, i.e. French art of the 19th century, symbolism in Russia and France, political iconography of monumental painting of the 19th century, and the history, formation and development of museums in Russia. In general, her sphere of interests lies where culture, power and issues of cultural life in modern Russia are overlapping.

Her lecture took place at the EUSP. It is necessary to say a few words about the place itself. The European University is an NGO, it was founded in 1994 and began its work with a post-graduate program in social sciences in 1996. It is an example of a post-graduate university, a type of institution very rare in Russia.

Unlike most of the typical PHD institutes, the EUSP educational curriculum lasts for 3–4 years and consists of lectures, seminars and conferences. It is famous for its critical attitude to the current government. This non-conformist attitude was even a reason for which the university was closed for a short period of time.

text by Dasha Paramonova

30

The university is located in a beautiful historic building which was donated at the time of Anatoliy Sobchak administration (1991–96). At that moment giving away such a building was a solution to protect it against the capture by private developers. Some original interiors are well preserved, some were totally destroyed in the Soviet period by the previous owner, the In-stitute of Occupational Safety and Health. This constant struggle, in which the building and its content become inseparably entangled, is, by and large, a major trend in the entire city.

In her lecture, Ms. Dolinina described the exis-tence of academic museums, their dependence on political regime and coexistence with con-temporary art.

The first part of the lecture was dedicated to the territorial expansion of the museum. Since the 1980s, the Russian Museum grew five times bigger. The Hermitage consists of six historic buildings, a few exhibition centres abroad and the General Staff Building, currently under reconstruction. Huge amount of square meters is not always used properly, but the museum’s self-confidence continuously grows. Paintings in the Russian Museum could be described in a few words: “big,” “political,” “popular.” Since the reign of Catherine II, the Hermitage has barely changed, even the position of each vase was written down and is still preserved untouched.

31

photo by Dasha Paramonova

Moreover, the Hermitage employees exist in a sealed world protected from any encroachment of the outside universe. It results in the emer-gence of a special caste of people—a specific kind of aristocracy. The museums are full of well-educated people who are not able to gen-erate a new approach to contemporary content. It is a very complex task to combine the impe-rial atmosphere with contemporary art. In other words, contemporary art is simply engulfed by vast spaces of the museums. There are only few curators capable of juxtaposing the space of a palace with modern content. As a result, the reception of contemporary art by the gener-al public is unfavourable. But, at the same time, modern art is not exhibited by other institutions because of the huge ambitions of the “great” museums and the lack of private funding.

However, capturing square meters in fact equals capturing people’s minds. Throughout the times of Mr. Putin, places related to impe-rial past became the paragons to be imitated by New Russia. Imperial ambition, as a con-sequence, became one of the most popular political trend in the past 20 years. I assume that this imperial awareness has spread—the physical bigness of the Hermitage reflects the geographical vastness of the whole country. This hypnotic bigness masks the absence of content, the stratification of society and the retrograde mood.

32

Conservation Strategy for a stationary system

The Heritage Conservation Strategy for St. Petersburg was developed by the State Committee of Control, Use and Protec-tion of Historical and Cultural Monuments (KGIOP) in 2005.This text analyzes Heritage Conservation Strategy as an intermediate document between two UNESCO declarations: those of 1990 and of 2011.

The first UNESCO declaration

In 1989, the Council of Ministers of the USSR started the application procedure to include Soviet monuments into the world heritage list. Leningrad was included in it in 1990. The application form listed the historic city center, the centers of small towns, suburban palaces and parks, the city and suburban highways, railway, land-scaped areas, landscapes along the Neva, its embankments, waterways, etc.ICOMOS reported: “The need for the inclusion of Leningrad into the World Heritage List is so obvious that a detailed substantiation seems unnecessary…” (S. Gorbatenko, one of the developers of the application). Using Prigozhin’s terminology (“order out of chaos”), one can say that preservation specialists saw Leningrad as a stationary system. Such a deterministic system treats the city as a mechanism that operates in linear conditions of order, stability and balance. “We serve a concept developed by UNESCO for our city as a single and unique urban development and historical-cultural monument, structurally divisible into systems and subsystems…” (A. Alekseev). On the one hand, the lack of tools to maintain such concept has led to increased conflicts between the public, experts on preservation, development businesses and politicians.

On the other hand, the city officials em-braced the Declaration as a political ges-ture which does not entail any aftereffects.

Institutions

I need to clarify that such institutions as construction and development organi-zations or government investment and construction bodies do not agree to preserve the city as a stationary system. At the same time, they advocate the basic principles of stationary systems.There are no significant changes in most of them for at least the last decade. For example, the “United Architectural Work-shops” were created in 1999. That union consists of 16 architectural companies which almost completely control the market of architectural services in St. Petersburg. The city council consisting of government and semi-government figures includes the same architects.

Conservation strategy

Heritage conservation strategy was initi-ated and developed with the direct par-ticipation of Vera Dementieva who is the KGIOP chairperson from 2003.According to Boris Kirikov’s words (at the time the first deputy chairman KGIOP), the general idea of the document was to bal-ance the current contradictions between society, business and bureaucracy.At the same time, the above-mentioned institutions weren’t involved in this pro-cess. The document is mostly a theory: it describes the benefits of the selected preservation pattern of city development, but suggests no practical steps towards its implementation.

text by Denis Leontiev

33

The contradictions are also in the fact that the preservation concept was developed during the time when the committee was supervised by St. Petersburg’s vice-gover-nor, whose main task was “urban devel-opment, investment in real estate, capital construction and reconstruction” (from the website of the city government).Governor signed the Preservation Strategy in 2005. This didn’t not lead to any chang-es in approaches to the development of the historical environment of the city. We can say that two relatively stationary sys-tems continue to ignore each other.Since the internal capabilities of such systems for change are very limited, they can’t resist the influence of open systems.World economic growth has provided the advantages of investment for the “con-struction system,” whereas the global economic crisis has provided benefits for the “preservation system.”Boris Kirikov said: “An economic crisis is a much better way to keep the historic cen-ter from destruction than any preservation declaration.”This partly explains the reason why the government asked the preservation com-munity to prepare a new UNESCO decla-ration.

The new declaration

Specialists involved in the preparation of a new application form are trying—as they did twenty years ago—to maximize the historic site area.Since, from 1989 on, the city found no adequate development mechanisms in the historic environment, this will lead to a new aggravation of contradictions in the new economic reality.

34

photo by Shi Yang

The State Hermitage is a museum of art and culture in Saint Petersburg, Russia. One of the largest and oldest museums of the world, it was founded in 1764 by Cath-erine the Great and open to the public since 1852. Its collections, of which only a small part is on permanent display, com-prise nearly 3 million items, including the largest collection of paintings in the world. The collections occupy a large complex of six historic buildings along Palace Em-bankment, including the Winter Palace, a former residence of Russian emperors. Apart from them, the Menshikov Palace, Museum of Porcelain, Storage Facility at Staraya Derevnya and the eastern wing of the General Staff Building are also part of the museum. The museum has several exhibition centers abroad. The Hermitage is a federal state property. Since 1990, the director of the museum has been Mikhail Piotrovsky.

37

photo by Dasha Paramonova

The Great HermitageIt was built in 1771-87 to the order of Catherine II and was intended to house the palace art collections and library. Yury Velten designed the three-storey building in such a way that it naturally completed the existing palace ensemble. The strictness and simplicity of the appearance of the Great Hermitge reflected the spirit of 18th-century Classicism.

The Winter PalaceIt is the biggest building in the entire museum complex of the Hermitage. It was commissioned by the daughter of Peter the Great, Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, in 1754 as an official royal residence. Construction went on until 1762. The design was prepared by an outstanding architect of the Baroque style, Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli.

The Small HermitageTo the order of Empress Catherine II, the Southern Pavilion of the Small Hermitage was erected in 1765-66 according to a design by the architect Yury Velten. The ap-pearance of this building organically combined the features of the Late Baroque style with Early Classicism. Later, in 1767- 69, the architect Jean Baptist Vallin de la Mothe constructed the Northern Pavilion on the bank of the Neva using the Early Classicism style.

38

Two Faces

“Renovation of historic spaces brings certain new qualities, but may also strip the buildings of their magical aura.” On

the photo: “The General Staff Building before and after renovation.”

Tremendous amount of renovations is quickly changing the image of Saint Petersburg. Yet it is not obvious if the effect of the ongoing changes is positive.

Architectural modifications which triggered the most interesting discussions during our excur-sion were mostly renovations of old courtyards. The space of a yard is relatively small, yet extremely important in the structure of this particular city. Its significance seems even more evi-dent after a renovation, which drastically changes its function and appearance. In a courtyard, one may see, as through a lens, the threats and opportunities of renovation.

A renovation of the space of an internal yard is seemingly a logical and natural step. An open space, so far used primarily for lighting, obtains a new function. Furthermore, renovation en-hances the functionality of a building and profitability of the plot. Refurbished walls of the inter-nal space finally become equally representative as the street façade. Covering the yard with a glass roof protects the interior space against the Saint Petersburg weather, while still providing enough sunlight.

text by Kuba Snopek

41

On the other hand, the fragmented process of renovation of small spaces does not necessarily add up to the improvement of the city as a whole. The consequences may be even opposite. It can lead to the disappearance of what is intriguing in Saint Petersburg’s layout: its dualism.

The primary public spaces of Saint Petersburg are streets, avenues and squares. They are representative, glamorous, pompous—as public spaces of an empire’s capital should be. But just few steps behind the street façade bring us to a different world: a labyrinth consisting of small irregular courtyards. This face of the city is dark, gloomy; it is in a permanent penumbra. Mysterious, dangerous and therefore inspirational. This sharp contrast between the calming beauty of the exterior and the seductive evil of the interior is an uncommon quality which has been exploited by writers, movie directors, artists.

An unwise massive renovation may lead to the irreversible loss of this quality. An architect dealing with this kind of refurbishment will always face series of inevitable contradictions. Is it right to convert a space of secondary importance into a main highlight of a building? Won’t it deprive the city from its unique dualism? Isn’t it a huge intrusion into the structure of the entire city to totally close spaces that, once being partially open, constituted part of a bigger system? Is it appropriate to totally replace the patina and imperfection of decay with perfect contempo-rary materials? Finally, is it worth, instead of ultimately turning St. Petersburg into a place full of glamorous perfection, allowing it to remain a city with two faces?

photos by Dasha Paramonova

42

Historic City Transformed

It is a fact that urban transformation processes have always existed, and the challenges of historic cities

like St. Petersburg are unique and varied. St. Petersburg is an incredible city founded by Peter the Great

on a desolate swamp, uninhabited no-man’s-land. From the 18th century on, the city has undergone

different transformations—just like its name, from St. Petersburg to Petrograd, and then from Leningrad

back to St. Petersburg. The old city center with its numerous monuments, squares and palaces shows

the splendid history of imperial Russia, while the Soviet power constructed its own center in the southern

outskirts of the city in the 1930s. We could clearly observe how St. Petersburg grew layer by layer, after

the manner of annual rings of a tree. Preserving the balance between preservation and transformation

during the growing process is a crucial issue.

Buildings possess a historic value that must be preserved; however, only a few of them having a really

high historic value or special importance stand a chance of being conserved as architectural monuments.

How could they be preserved? Renewing their physical substance is not enough; we need to consider

further how to revitalize their spirit. Except for a limited number of vintage structures that could serve as

architectural showcases, parks, museums, etc., most of them face some form of transformation to adapt

them to the current conditions of urban development: like housing, commercial centers or offices. Interior

refurbishment, substitution of materials, extension of existing structures, and other various modifications

are implemented in historic buildings.

The slice of St. Petersburg that I selected for my field trip, Moskovsky Avenue, covers a 10 km area from

city center to the outskirts. It runs from Sennaya Square and Sadovaya Street to the Victory Square, and

ultimately leads to Moscow. Basically, the avenue is divided into three sections, the first one from Sen-

naya Square to Obvodny Canal, which is the core of historic center. The second one starts from Moscow

Triumphal Arch to Victory Square which is mostly covered with Stalin period structures and monuments

built during the Soviet era. The third one is a “buffer zone” between the imperial center and the Soviet

city.

photo and text by Shi Yang

PALACE SQUAREDistrict Council of Moscow

1930-35

Triumphal Arch

Industrial

1834 -1838 1950’s

Frunze Department

1934-38

Institute of Technology

1828

Sennaya Square

1737

Stalinist Block

1930s

New Russian National Library

1998

Luxury Housing

2011

Luxury Housing

2011

House of Soviets Victory Square

1930’s1975

Due to the large ratio of preserved historic buildings—including monuments, entire blocks, pieces of

environment, etc.—in the center, it’s impossible to implement large-scale urban transformation. Recently,

experts started to discuss including the Soviet portion of the city into the list of protected monuments, so

that there would be less and less room for new spatial modifications. There are several ways of transfor-

mation that were applied to Moskovsky Avenue. One of them involves renovating historic buildings with

a view of using them for new urban functions. For instance, the House of Soviets located at the southern

part of the avenue used to be a local commanding center of the Red Army, becoming later a research in-

stitute that focused on the design of electronic components for military objects. Currently, the office space

of the building is rented out to various businesses. The facade and decorations still preserve their original

Stalinist style, but the interior is a totally different world. Another way of urban transformation in Mosk-

ovsky Avenue is inserting entirely new elements into its historic urban context. There are two large luxury

quarters under construction now; one is next to the House of Soviets, the other one, near the historical

center.

Will there be restrictions or special requirements for construction works and design modifications in the

vicinity of historic buildings? As new “slices” of the St. Petersburg “pie” are being added to the protection

list, will currently new neighborhoods be declared heritage in the future?

Transformation is inevitable in the city that grows in both tangible and intangible ways. For the historic cit-

ies, preservation and transformation are complementary to each other. It is through preservation that we

can change the mechanism of urban development, and it is through new design and certain restrained

modifications that we can revitalize the historical center.

PALACE SQUAREDistrict Council of Moscow

1930-35

Triumphal Arch

Industrial

1834 -1838 1950’s

Frunze Department

1934-38

Institute of Technology

1828

Sennaya Square

1737

Stalinist Block

1930s

New Russian National Library

1998

Luxury Housing

2011

Luxury Housing

2011

House of Soviets Victory Square

1930’s1975