Spontaneus Pneumothorax

Transcript of Spontaneus Pneumothorax

-

8/10/2019 Spontaneus Pneumothorax

1/2

SPONTANEOUS PNEUMOTHORAX

Acute onset of unilateral chest pain and dyspnea.

Minimal physical findings in mild cases; unilateral chest expansion, decreasedtactile fremitus, hyperresonance, diminished breath sounds, mediastinal shift,cyanosis and hypotension in tension pneumothorax.

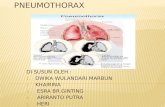

Presence of pleural air on chest radiograph.Esse ntials of diagnosisGeneral ConsiderationsPneumothorax, or accumulation of air in the pleural space, is classified as spontaneous

(primary or secondary) or traumatic. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in the

absence of an underlying lung disease, whereas secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is a

complication of preexisting pulmonary disease. Traumatic pneumothorax results from

penetrating or blunt trauma. Iatrogenic pneumothorax may follow procedures such as

thoracentesis, pleural biopsy, subclavian or internal jugular vein catheterplacement,

percutaneous lung biopsy, bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy, and positive-pressure

mechanical ventilation. Tension pneumothorax usually occurs in the setting of penetrating

trauma, lung infection, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or positive-pressure mechanicalventilation. In tension pneumothorax, the pressure of air in the pleural space exceeds ambient

pressure throughout the respiratory cycle. A check-valve mechanism allows air to enter the

pleural space on inspiration and prevents egress of air on expiration. Primary pneumothorax

affects mainly tall, thin boys and men between the ages of 10 and 30 years. It is thought to

occur from rupture of subpleural apical blebs in response to high negative intrapleural

pressures. Family history and cigarette smoking may also be important factors. Secondary

pneumothorax occurs as a complication of COPD, asthma, cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis,

Pneumocystis pneumonia, menstruation (catamenial pneumothorax), and a wide variety of

interstitial lung diseases including sarcoidosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Langerhans cell

histiocytosis, and tuberous sclerosis. Aerosolized pentamidine and a prior history of

Pneumocystis pneumonia are considered risk factors for the development of pneumothorax.

One-half of patients with pneumothorax in the setting of recurrent (but not primary)

Pneumocystispneumonia will develop pneumothorax on the contralateral side. The mortality

rate of pneumothorax inPneumocystispneumonia is high.

Clinical FindingsA. Symptoms and SignsChest pain ranging from minimal to severe on the affected side and dyspnea occur in nearly

all patients. Symptoms usually begin during rest and usually resolve within 24 hours even if

the pneumothorax persists. Alternatively, pneumothorax may present with life-threatening

respiratory failure if underlying COPD or asthma is present. If pneumothorax is small ( 15%

of a hemithorax), physical findings, other than mild tachycardia, are normal. If pneumothoraxis large, diminished breath sounds, decreased tactile fremitus, and decreased movement of the

chest are often noted. Tension pneumothorax should be suspected in the presence of marked

tachycardia, hypotension, and mediastinal or tracheal shift.

B. Laboratory FindingsArterial blood gas analysis is often unnecessary but reveals hypoxemia and acute respiratory

alkalosis in most patients. Left-sided primary pneumothorax may produce QRS axis and

precordial T wave changes on the ECG that may be misinterpreted as acute myocardial

infarction.

C. ImagingDemonstration of a visceral pleural line on chest radiograph is diagnostic and may only be

seen on an expiratory film. A few patients have secondary pleural effusion that demonstrates acharacteristic air-fluid level on chest radiography. In supine patients, pneumothorax on a

-

8/10/2019 Spontaneus Pneumothorax

2/2

conventional chest radiograph may appear as an abnormally radiolucentcostophrenic sulcus

(the deep sulcus sign). In patients with tension pneumothorax, chest radiographs show a

large amount of air in the affected hemithorax and contralateral shift of the mediastinum.

Differential DiagnosisIf the patient is a young, tall, thin, cigarette-smoking man, the diagnosis of primary

spontaneous pneumothorax is usually obvious and can be confirmed by chest radiograph. Insecondary pneumothorax, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish loculated pneumothorax

from an emphysematous bleb. Occasionally, pneumothorax may mimic myocardial infarction,

pulmonary embolism, or pneumonia.

ComplicationsTension pneumothorax may be life-threatening. Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous

emphysema may occur as complications of spontaneous pneumothorax. If

pneumomediastinum is detected, rupture of the esophagus or a bronchus should be

considered.

TreatmentTreatment depends on the severity of pneumothorax and the nature of the underlying disease.

In a reliable patient with a small ( 15% of a hemithorax), stable spontaneous primarypneumothorax, observation alone may be appropriate. Many small pneumothoraces resolve

spontaneously as air is absorbed from the pleural space; supplemental oxygen therapy may

increase the rate of reabsorption. Simple aspiration drainage of pleural air with a small-bore

catheter (eg, 16 gauge angiocatheter or larger drainage catheter) can be performed for

spontaneous primary pneumothoraces that are large or progressive. Placement of a small-bore

chest tube (7F to 14F) attached to a one-way Heimlich valve provides protection against

development of tension pneumothorax and may permit observation from home. The patient

should be treated symptomatically for cough and chest pain, and followed with serial chest

radiographs every 24 hours. Patients with secondary pneumothorax, large pneumothorax,

tension pneumothorax, or severe symptoms or those who have a pneumothorax on mechanical

ventilation should undergo chest tube placement (tube thoracostomy). The chest tube is placed

under water-seal drainage, and suction is applied until the lung expands. The chest tube can be

removed after the air leak subsides. All patients who smoke should be advised to discontinue

smoking and warned that the risk of recurrence is 50%. Future exposure to high altitudes,

flying in unpressurized aircraft, and scuba diving should be avoided. Indications for

thoracoscopy or open thoracotomy include recurrences of spontaneous pneumothorax, any

occurrence of bilateral pneumothorax, and failure of tube thoracostomy for the first episode

(failure of lung to reexpand or persistent air leak). Surgery permits resection of blebs

responsible for the pneumothorax and pleurodesis by mechanical abrasion and insufflation of

talc. Management of pneumothorax in patients with Pneumocystispneumonia is challenging

because of a tendency toward recurrence, and there is no consensus on the best approach. Useof a small chest tube attached to a Heimlich valve has been proposed to allow the patient to

leave the hospital. Some clinicians favor its insertion early in the course.

PrognosisAn average of 30% of patients with spontaneous pneumothorax experience recurrence of the

disorder after either observation or tube thoracostomy for the first episode. Recurrence after

surgical therapy is less frequent. Following successful therapy, there are no long-term

complications.