artikel pneumothorax

-

Upload

mariekewalen -

Category

Documents

-

view

235 -

download

4

Transcript of artikel pneumothorax

Spontaneous Pneumothorax Caused byPulmonary Blebs and Bullae in 12 Dogs

Spontaneous pneumothorax caused by pulmonary blebs and bullae was diagnosed in 12 dogsbased on history, clinical examination, thoracic radiographs, surgical findings, and histopathologi-cal examination of resected pulmonary lesions. Radiographic evidence of blebs or bullae wasseen in only one dog. None of the dogs responded to conservative treatment with thoracocente-sis or thoracostomy tube drainage. A median sternotomy approach was used to explore the tho-rax in all dogs. Pulmonary blebs and bullae were resected with partial or complete lunglobectomy. Ten of the dogs had more than one lesion, and seven of the dogs had bilaterallesions. The cranial lung lobes were most commonly affected. Histopathology results of the blebsand bullae were consistent in all dogs and resembled lesions found in humans with primary spon-taneous pneumothorax. None of the dogs developed recurrence of pneumothorax. Median fol-low-up time was 19 months. The outcome following resection of the pulmonary blebs and bullaewas excellent. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2003;39:435–445.

Victoria J. Lipscomb, MA, VetMB,MRCVS, CertSAS, Diplomate ECVS

Robert J. Hardie, DVM,Diplomate ACVS, Diplomate ECVS

Richard R. Dubielzig, DVM,Diplomate ACVP

IntroductionSpontaneous pneumothorax occurs when air or gas enters the pleuralspace in the absence of a traumatic or iatrogenic cause.1-4 The most com-mon source of air is the lung parenchyma; however, other sources includethe trachea, bronchi, and esophagus or gas-forming organisms within thepleural cavity.1 Spontaneous pneumothorax can be further classified aseither primary or secondary based on the history, clinical signs, andwhether an underlying cause can be determined from diagnostic tests,such as thoracic radiographs, thoracic computed tomography (CT), orthoracoscopy.4-7 Reported causes of spontaneous pneumothorax in dogsinclude bacterial pneumonia, pulmonary abscesses, dirofilariasis, pul-monary neoplasia, bullous emphysema, and pulmonary blebs and bullae.8

Based on previous reports, the most common cause of spontaneous pneu-mothorax is pulmonary blebs or bullae.2,3,7,9

Pulmonary blebs are accumulations of air within the layers of the vis-ceral pleura, most commonly located at the lung apices [Figure 1].6

They form when air escapes from within the lung parenchyma and trav-els to the surface of the lung and becomes trapped between the layers ofthe visceral pleura.6 Grossly, blebs appear as small “bubbles” or “blister-like” lesions on the surface of the lung that range in size up to severalcentimeters in diameter.

In contrast, pulmonary bullae are air-filled spaces within the lungparenchyma that result from the destruction, dilatation, and confluenceof adjacent alveoli.6 Bullae can vary in size, with some being small(involving only a few alveoli) and others being very large (involving amajority of the lung).10 Bullae are confined by the connective tissuesepta within the lung and the internal layer of the visceral pleura. Bullaehave been classified into three types based on the size and connectionwith surrounding lung tissue [Figure 1].6 Type 1 bullae are thin, withempty interiors and a small, narrow connection to the pulmonaryparenchyma. They are usually found at the apices of the lung andhave outer walls that may or may not be lined by mesothelial cells on the

JOURNAL of the American Animal Hospital Association 435

From the Department of Small AnimalMedicine and Surgery (Lipscomb),

Royal Veterinary College,University of London,

Hawkshead Lane, North Mymms,Hertfordshire, AL9 7TA England

and the Departments of Surgical Sciences (Hardie)

and Pathobiological Sciences (Dubielzig),School of Veterinary Medicine,

University of Wisconsin,2015 Linden Drive,

Madison, Wisconsin 53706.

Address all correspondence to Dr. Hardie.

RS

external surface. Type 2 bullae arise from the subpleuralparenchyma and are connected to the rest of pulmonaryparenchyma by a neck of emphysematous lung. The interiorof the bullae is filled with emphysematous lung tissue, and

the outer walls are formed by intact pleura lined bymesothelial cells. Type 3 bullae can be very large and maycontain emphysematous lung tissue that extends deep intothe pulmonary parenchyma.

436 JOURNAL of the American Animal Hospital Association September/October 2003, Vol. 39

Figure 1—Line drawings illustrating the apex of the lung (shaded box in top drawing) and a pulmonary bleb (A), type 1bulla (B), type 2 bulla (C), and type 3 bulla (D). Note the accumulation of air between the layers of the visceral pleura inthe pulmonary bleb and the different connections to the underlying pulmonary parenchyma in B, C, and D.

Several reports have described the clinical findings fromdogs with spontaneous pneumothorax due to pulmonaryblebs, bullae, or bullous emphysema; however, differencesin lesion terminology, lesion description, and histopatholog-ical interpretation have resulted in conflicting informationabout pulmonary bleb and bulla lesions.2,3,7,9 In particular,the terms bleb, bulla, and bullous emphysema have beenused interchangeably in some reports, making it difficult todetermine the specific lesion being described. Also, thelocation and extent of the pulmonary lesions were notalways reported, making it unclear as to whether lesionswere focal, multifocal, or diffuse. Finally, differing inter-pretations of the histopathological findings has resulted inuncertainty as to whether pulmonary blebs and bullaeshould be considered primary lesions or lesions thatdevelop secondary to some other underlying cause.

The purpose of this study is to describe the clinicalsigns, radiographic findings, surgical treatment, postopera-tive complications, histopathological findings, and long-term outcome of 12 dogs with spontaneous pneumothoraxcaused by focal pulmonary blebs and bullae. In addition,the findings of this study are compared to those describedfor humans with primary spontaneous pneumothorax due topulmonary blebs and bullae.

Materials and MethodsCase MaterialThe records of dogs diagnosed with spontaneous pneu-mothorax caused by pulmonary blebs and bullae at theRoyal Veterinary College, University of London, betweenMay 1991 and September 2000 were reviewed. The signal-ment, history, prior treatment, physical examination find-ings, complete blood count (CBC) and serum biochemicalprofile findings, initial management, radiographic findings,surgical technique, histopathological findings, postoperativecomplications, and long-term outcome were recorded. Anydog with a history of trauma or underlying pulmonary dis-ease, such as neoplasia or pneumonia, was excluded fromthe study.

Initial ManagementPhysical examination, CBC, and serum biochemical profilewere performed on all dogs. Pneumothorax was treated ini-tially with intermittent thoracocentesis or placement of athoracostomy tube. Serial lateral and dorsoventral radio-graphs of the thorax were made after thoracic drainage.Spontaneous pneumothorax was diagnosed if evidence oftrauma was excluded based on history, clinical signs, andthoracic radiographs. The duration and outcome of initialtreatment with thoracocentesis or thoracostomy tubedrainage were recorded.

Surgical TechniqueA median sternotomy was performed on all dogs, and thelungs were inspected for lesions. If the source of leakage wasnot readily identified, the thorax was filled with warm, sterilesaline and leaks were located during ventilation. All visible

lesions were removed by partial or complete lung lobectomy.Partial lung lobectomies were performed by stapling the lungparenchyma using an automatic stapling devicea and resect-ing the lesion distal to the staple line. Complete lung lobec-tomies were performed by double ligating the pulmonaryvasculature, staplinga the bronchus, and resecting the lungdistal to the staples. Staple lines were checked for leakage byfilling the thorax with warm, sterile saline and inflating thelungs. A thoracostomy tube was placed, and the thorax wasclosed with stainless steel wire placed around the sternebraein a cruciate pattern. The description and location of theresected lesions were recorded.

Postoperative ManagementThe dogs were monitored after surgery, and intramuscularmorphine,b intrapleural bupivacaine,c or both were given asrequired for analgesia. The thoracostomy tubes were aspi-rated as necessary, and the time of removal was recorded.The sternotomy incisions were monitored, and complica-tions were recorded.

Long-Term Follow-upFollow-up information was obtained by clinical examina-tion or by telephone conversation with the owner. Details ofexercise tolerance and respiratory effort were recorded. Ifthe dog was no longer alive, the cause of death and timesince the surgery were recorded.

Histopathological ExaminationThe resected lung tissue was preserved in 10% formalin,embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hema-toxylin and eosin. Histopathological examination was per-formed by the same pathologist (Dubielzig).

ResultsSignalment and HistoryTwelve dogs were identified with spontaneous pneumotho-rax caused by pulmonary blebs or bullae [Table 1]. Eightdogs were purebreds, and four were mixed-breed dogs. Alldogs were either large breed or had deep-chested conforma-tion. The median age was 7.5 years (range, 3.5 to 12 years),and the median weight was 25 kg (range, 9.9 to 42 kg).There were seven males and five females. Eleven of 12dogs had a history of intermittent or progressive dyspneathat was acute in onset for some dogs. Other clinical signsincluded lethargy, anorexia, depression, coughing, and exer-cise intolerance. Eight dogs were treated with thoracocente-sis, and one dog was treated with thoracostomy tubedrainage prior to referral.

Physical Examination, Radiography, and InitialManagementPhysical examination revealed varying degrees of tachycar-dia, tachypnea, increased respiratory effort, and respiratorydistress. Auscultation of the thorax revealed decreased lungsounds on one or both sides. Complete blood count andserum biochemical profile results were within reference

September/October 2003, Vol. 39 Pulmonary Blebs and Bullae 437

438 JOURNAL of the American Animal Hospital Association September/October 2003, Vol. 39

Tab

le 1

Sig

nalm

ent,

His

tory

, Ini

tial M

anag

emen

t, R

adio

grap

hic

Fin

ding

s, S

urge

ry, C

ompl

icat

ions

, and

Lon

g-Te

rm O

utco

me

in 1

2 D

ogs

With

Spo

ntan

eous

Pne

umot

hora

x

Cas

eIn

itia

lR

adio

gra

ph

icL

on

g-T

erm

No

.S

ign

alm

ent*

His

tory

Man

agem

ent

Fin

din

gs

Su

rger

yC

om

plic

atio

ns

Ou

tco

me

17-

yr, 1

5-kg

, MD

yspn

ea fo

rT

hora

cost

omy

Bila

tera

lB

ilate

ral l

esio

ns.

Non

eLo

st to

follo

w-u

p af

ter

2-m

osm

ixed

-bre

ed3

wee

ks,

tube

for

48 h

rspn

eum

otho

rax

Par

tial r

ight

mid

dle

reex

amin

atio

n. N

odo

gm

anag

ed b

yan

d co

mpl

ete

left

recu

rren

ce o

f clin

ical

sig

ns a

tth

orac

ocen

tesi

scr

ania

l lun

gth

at ti

me

lobe

ctom

y

27.

5-yr

, 35.

4-kg

,In

term

itten

tT

hora

cost

omy

Left

pneu

mot

hora

xB

ilate

ral l

esio

ns.

Non

eD

ied

of h

epat

ic d

isea

se a

fter

FS

Old

Eng

lish

dysp

nea

for

9tu

be fo

r 48

hrs

Par

tial r

ight

cra

nial

36 m

os; n

o re

curr

ence

of

shee

pdog

days

, man

aged

by

and

com

plet

e le

ftcl

inic

al s

igns

thor

acoc

ente

sis

cran

ial l

ung

lobe

ctom

y

37-

yr, 4

2-kg

, MN

Acu

te-o

nset

Tho

raco

cent

esis

Bila

tera

lB

ilate

ral l

esio

ns.

Rec

urre

ntD

ied

acut

ely

afte

r 36

mos

mix

ed-b

reed

dysp

nea,

man

aged

for

24 h

rspn

eum

otho

rax;

Par

tial r

ight

cra

nial

,pn

eum

otho

rax

afte

r(c

ause

of d

eath

unk

now

n); n

ow

olfh

ound

by d

aily

bulla

in le

ft ca

udal

part

ial l

eft c

auda

l,su

rger

y du

e to

recu

rren

ce o

f clin

ical

sig

nsth

orac

ocen

tesi

s fo

rlu

ng lo

bean

d co

mpl

ete

leak

age

from

a s

tapl

e7

days

acce

ssor

y lu

nglin

e; tr

eate

d by

lobe

ctom

yre

stap

ling

the

lung

46-

yr, 9

.9-k

g, F

Dys

pnea

and

Tho

raco

stom

yLe

ft pn

eum

otho

rax

Uni

late

ral l

esio

ns.

Non

eLo

st to

follo

w-u

p im

med

iate

lym

ixed

-bre

edex

erci

se in

tole

ranc

etu

be fo

r 6

days

and

Com

plet

e le

ftaf

ter

surg

ery

dog

for

6 w

eeks

,pn

eum

omed

iast

inum

cran

ial l

ung

man

aged

by

lobe

ctom

yth

orac

osto

my

tube

for

10 d

ays

59.

75-y

r, 31

.5-k

g,A

cute

-ons

etT

hora

cost

omy

Bila

tera

lU

nila

tera

l les

ions

.E

dem

a ar

ound

inci

sion

;D

ied

of g

astr

oent

eriti

s af

ter

M s

tand

ard

dysp

nea

and

tube

with

pneu

mot

hora

xC

ompl

ete

left

sutu

re r

emov

al d

elay

ed24

mos

; no

recu

rren

ce o

fpo

odle

coug

hing

, man

aged

cont

inuo

uscr

ania

l lun

gcl

inic

al s

igns

by th

orac

ocen

tesi

ssu

ctio

n ap

plie

dlo

bect

omy

and

emer

genc

yfo

r se

vera

l hou

rs,

refe

rral

cont

inue

dle

akag

e,em

erge

ncy

ster

noto

my

(co

nti

nu

ed o

n n

ext

pag

e)

September/October 2003, Vol. 39 Pulmonary Blebs and Bullae 439

Tab

le 1

(co

nt’d

)

Sig

nalm

ent,

His

tory

, Ini

tial M

anag

emen

t, R

adio

grap

hic

Fin

ding

s, S

urge

ry, C

ompl

icat

ions

, and

Lon

g-Te

rm O

utco

me

in 1

2 D

ogs

With

Spo

ntan

eous

Pne

umot

hora

x

Cas

eIn

itia

lR

adio

gra

ph

icL

on

g-t

erm

No

.S

ign

alm

ent*

His

tory

Man

agem

ent

Fin

din

gs

Su

rger

yC

om

plic

atio

ns

Ou

tco

me

66.

5-yr

, 22.

5-kg

,D

yspn

ea a

ndT

hora

cost

omy

Bila

tera

lB

ilate

ral l

esio

ns.

Non

eD

ied

of s

plen

icF

S G

erm

anex

erci

setu

be fo

r 24

hrs

pneu

mot

hora

xC

ompl

ete

right

hem

angi

osar

com

a af

ter

6 m

os;

shep

herd

dog

into

lera

nce

for

18cr

ania

l and

par

tial

no r

ecur

renc

e of

clin

ical

sig

nsda

ys, m

anag

ed b

yle

ft cr

ania

l lun

gth

orac

ocen

tesi

slo

bect

omy

710

-yr,

28.4

-kg,

Acu

te-o

nset

Tho

raco

stom

yB

ilate

ral

Uni

late

ral l

esio

ns.

Non

eD

ied

of n

eopl

asia

on

digi

t afte

r 8

M L

abor

ador

dysp

nea,

man

aged

tube

for

24 h

rspn

eum

otho

rax

Par

tial r

ight

cra

nial

mos

; no

recu

rren

ce o

f clin

ical

retr

ieve

rby

thor

acoc

ente

sis

lung

lobe

ctom

ysi

gns

for

5 da

ys

88.

6-yr

, 37.

6-kg

,D

yspn

ea a

ndT

hora

cost

omy

Bila

tera

lU

nila

tera

l les

ion.

Ser

oma

arou

nd in

cisi

on,

Aliv

e at

40

mos

; no

FS

Ger

man

anor

exia

for

5 da

ystu

be fo

r 4

days

pneu

mot

hora

xC

ompl

ete

right

reso

lved

ove

r 10

day

sre

curr

ence

of c

linic

al s

igns

shep

herd

dog

cran

ial l

ung

lobe

ctom

y

93.

5-yr

, 12-

kg, M

Dys

pnea

for

3 w

eeks

,T

hora

cost

omy

Left

pneu

mot

hora

x,B

ilate

ral l

esio

ns.

Ede

ma

with

Aliv

e at

22

mos

; no

recu

rren

ce o

fw

hipp

etm

anag

ed b

ytu

be fo

r 3

days

pneu

mom

edia

stin

um,

Par

tial l

eft c

rani

al,

sero

sang

uine

ous

clin

ical

sig

nsth

orac

ocen

tesi

sce

rvic

al/th

orac

icpa

rtia

l rig

ht c

rani

al,

disc

harg

e fr

om in

cisi

on,

subc

utan

eous

and

part

ial r

ight

reso

lved

with

ban

dagi

ngem

phys

ema

mid

dle

lung

and

antib

iotic

slo

bect

omy

103.

5-yr

, 38-

kg, F

Dys

pnea

for

3 w

eeks

,T

hora

cost

omy

Bila

tera

lU

nila

tera

l les

ion.

Ser

oma

arou

nd in

cisi

on,

Aliv

e at

16

mos

; no

recu

rren

ce o

fO

ld E

nglis

hm

anag

ed b

ytu

be fo

r 5

days

pneu

mot

hora

xP

artia

l rig

ht c

rani

alre

solv

ed o

ver

2 w

eeks

clin

ical

sig

nssh

eepd

ogth

orac

ocen

tesi

slu

ng lo

bect

omy

119.

6-yr

, 16.

7-kg

,P

oor

oxyg

enT

hora

coce

ntes

isR

ight

pne

umot

hora

xB

ilate

ral l

esio

ns.

Non

eA

live

at 1

0 m

os; n

o re

curr

ence

of

MN

rou

gh-c

oate

dsa

tura

tion

durin

gfo

r 3

days

Par

tial r

ight

and

left

clin

ical

sig

nsco

llie

rout

ine

anes

thes

iacr

ania

l lun

g lo

bect

omy

1212

-yr,

14-k

g, M

Acu

te-o

nset

dys

pnea

Tho

raco

stom

yB

ilate

ral

Bila

tera

l les

ions

.N

one

Aliv

e at

6 m

os; n

o re

curr

ence

of

mix

ed-b

reed

dog

over

1 d

aytu

be fo

r 2

days

pneu

mot

hora

xP

artia

l rig

ht a

nd le

ftsi

gns

cran

ial l

ung

lobe

ctom

y

*M

=m

ale;

FS

=fe

mal

e sp

ayed

; MN

=m

ale

neut

ered

; F=

fem

ale

ranges. Radiographs of the thorax revealed bilateral pneu-mothorax in eight dogs and unilateral pneumothorax in fourdogs [Table 1]. Two dogs had pneumomediastinum, and onedog had subcutaneous emphysema over the cervical and tho-racic areas. A 2-cm bulla was identified in the left caudal lunglobe on dorsoventral radiographs in case no. 3. None of theother dogs had pulmonary lesions identified on radiographs.

Initial treatment consisted of thoracostomy tube drainagefor 10 of the dogs and thoracocentesis for two dogs. Forcase no. 3, thoracocentesis was performed as necessary, andsurgery was performed the following day. For case no. 5,placement of a thoracostomy tube and the use of continuoussuction could not control the pneumothorax, and an emer-gency median sternotomy was performed the day of admis-sion. For the other 10 dogs, thoracostomy tubes were inplace for 1 to 5 days prior to surgery. Pneumothorax per-sisted in all of the dogs despite conservative treatment witheither thoracocentesis or thoracostomy tube drainage.

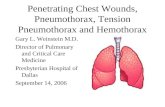

Surgical FindingsBleb and bulla lesions appeared as thin, focal, translucent,“bubble-like” lesions on the apical margins of the affectedlung lobes in all dogs, varying in size up to several centime-ters in diameter [Figure 2]. In some dogs, the bleb and bullalesions had a similar appearance, and it was not possible todistinguish the differences between the lesions on grossinspection. Ten of the 12 dogs had more than one lesion,and seven of 12 had bilateral lesions [Table 1]. In all of thedogs, one or both cranial lung lobes had lesions. The acces-sory lung lobe and left caudal lung lobe (bulla identified onradiographs) were also affected in case no. 3, and the rightmiddle lung lobe was also affected in case nos. 1 and 9. Indogs with multiple lesions, not all were leaking at the timeof surgery. The rest of the lungs appeared grossly normal.

Postoperative Management and ComplicationsPneumothorax occurred in the immediate postoperativeperiod in case no. 3 due to leakage from the staple line of apartial lung lobectomy. A second surgery was performed torestaple the lung, and the pneumothorax resolved. Thora-costomy tubes were removed between 1 and 6 days aftersurgery. A seroma developed at the sternotomy incision infour dogs. In three of the dogs, the seroma resolved withoutany treatment. In the fourth dog (case no. 9), the incisionwas bandaged and antibiotic therapy was continued for 2weeks before resolution. There were no recurrences ofpneumothorax due to pulmonary blebs or bullae in theimmediate postoperative period.

Histopathological FindingsHistopathological examination was performed on represen-tative samples of resected lung tissue from all dogs exceptcase nos. 3 and 7 [Table 2]. Histopathological findings ofthe pulmonary lesions were similar in all dogs. Focal bleblesions were identified in two dogs (case nos. 8, 10) [Figure3], focal bulla lesions were identified in six dogs (case nos.1, 5, 6, 10-12) [Figure 4], and multiple bullae were identi-fied in one dog (case no. 2). In two dogs (case nos. 4, 9),

disruption of the superficial portion of the lesion duringpreservation made it difficult to accurately determinewhether the lesion was a bleb or bulla, although the sur-rounding changes were similar to those found in the otherbleb and bulla lesions. Five dogs (case nos. 1, 2, 6, 11, 12)had bullae that most closely resembled the type 1 classifica-tion, and two dogs (case nos. 5, 10) had bullae that resem-bled the type 2 classification. The focal changessurrounding the bleb and bulla lesions included dilatedalveoli and peripheral emphysema, smooth-muscle hyper-trophy surrounding the respiratory ducts, mild to moderateperivascular lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, chronic col-lapse of adjacent parenchyma, and black foreign particulatematter. No underlying cause for the lesions was identifiedin any dog, although smooth-muscle hypertrophy was sug-gestive of a chronic change. The foreign particulate mate-rial present in the lungs was most likely carbon frominhaled smoke or other pollutants in the environment,which is often seen in the lungs of normal dogs.

440 JOURNAL of the American Animal Hospital Association September/October 2003, Vol. 39

Figures 2A, 2B—Intraoperative photographs of pulmonarybullae on the apical margin of the right and left cranial lunglobes from case no. 12.

A

B

Long-term OutcomeLong-term information was available from 10 of the dogs[Table 1]. Five dogs were still alive at the time of writing,with no recurrence of pneumothorax 6, 10, 16, 22, and 40months after surgery. Four dogs died from unrelated prob-lems, with no recurrence of pneumothorax 6, 8, 24, and 36months after surgery. One dog (case no. 3) collapsed anddied suddenly 36 months after surgery. The cause of deathwas unknown; however, signs of pneumothorax had notbeen reported previously. Information was not available fortwo dogs 1 week and 2 months after surgery. The medianfollow-up time for the 10 dogs with long-term informationwas 19 months (range, 6 to 40 months).

DiscussionDiagnosis and treatment of spontaneous pneumothoraxcaused by pulmonary blebs and bullae in dogs can be par-ticularly challenging since the source of air leakage is notusually evident from the history, clinical examination, orthoracic radiographs.2,3,7,9 Understanding the typical clini-cal signs, radiographic findings or lack thereof, response toconservative and surgical treatment, and gross andhistopathological characteristics is essential for making thediagnosis and providing appropriate treatment. In addition,understanding how bleb and bulla lesions in dogs compareto those found in humans is necessary so that diagnosticand treatment strategies developed for humans can beapplied appropriately to dogs.

Based on the results of this study, pulmonary blebs orbullae are found most often in healthy, middle-aged, large-breed or deep-chested dogs that have no previous history ofrespiratory problems or lung disease. The most commonclinical signs include lethargy, anorexia, depression, cough-ing, tachypnea, exercise intolerance, increased respiratoryeffort, and various degrees of respiratory distress. For somedogs, respiratory signs may develop rapidly and be veryobvious, whereas for other dogs, initial clinical signs maybe very nonspecific and respiratory signs may not developuntil the pneumothorax progresses over days.

Initial treatment should focus on stabilizing the dog withstrict rest, oxygen supplementation, and thoracic drainage.Thoracocentesis should be performed as often as necessaryto maintain adequate respiration. For dogs with more rapidaccumulation of air, a thoracostomy tube should be placedto allow more frequent drainage of the thorax or the use ofcontinuous suction.

Definitive diagnosis of pulmonary blebs and bullae canbe difficult since the lesions are not usually apparent onthoracic radiographs.2,7 Due to their relatively small sizeand location on the margins of the lungs, most blebs andbullae are not usually seen unless they become very large ordevelop thickened walls. Nevertheless, serial thoracic radio-graphs should be taken to identify other potential causes ofpneumothorax such as pulmonary neoplasia, abscesses, ordirofilariasis.2,7,8 In this study, all of the dogs had variousdegrees of unilateral or bilateral pneumothorax, and in onlyone dog (case no. 3) was a bulla identified on radiographs.The bulla was located in the left caudal lung lobe; however,at surgery, additional bullae were discovered on other lunglobes. The use of thoracic computed tomography (CT) orthoracoscopy for the diagnosis of pulmonary blebs and bul-lae has not been reported in a series of dogs; however, theiruse warrants investigation and may prove more accuratethan radiographs for identifying small pulmonary lesions.Other diagnostic tests, such as a CBC and serum biochemi-cal profile, are not usually helpful for determining the causeof pneumothorax, although they may identify other concur-rent problems.3,9

Conservative treatment with thoracocentesis or thoracos-tomy tube drainage was not effective in resolving the pneu-mothorax in any of the dogs in this study. Pneumothorax

September/October 2003, Vol. 39 Pulmonary Blebs and Bullae 441

Figure 3—Photomicrograph of a pulmonary bleb from caseno. 8. Air has accumulated between the layers of the vis-ceral pleura. There is marked pleural thickening but note thelack of an epithelial lining, and there is no indication of aconnection between the air-filled space and the pulmonaryparenchyma. There is peripheral emphysematous changeand muscular hypertrophy around the respiratory ducts(Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 200×).

Figure 4—Photomicrograph of a pulmonary bulla from caseno. 1. Note the connection between the bulla and the under-lying lung parenchyma and the presence of an epithelial lin-ing. There is marked peripheral emphysematous changeand focal atelectasis. There is muscular hypertrophy aroundrespiratory ducts and a moderate amount of particulate for-eign material around the bronchioles (Hematoxylin andeosin stain, 20×).

442 JOURNAL of the American Animal Hospital Association September/October 2003, Vol. 39

Tab

le 2

His

topa

thol

ogic

al F

indi

ngs

in 1

2 D

ogs

With

Pul

mon

ary

Ble

bs o

r B

ulla

e

Cas

e N

o.

His

top

ath

olo

gic

al F

ind

ing

s F

rom

Var

iou

s R

epre

sen

tati

ve L

esio

ns

Su

bm

itte

d fo

r E

xam

inat

ion

1B

ulla

(ty

pe 1

). P

erip

hera

l em

phys

emat

ous

chan

ge. E

xten

sive

ate

lect

asis

and

mod

erat

e m

uscu

lar

hype

rtro

phy

arou

nd a

irway

s. M

oder

ate

part

icul

ate

fore

ign

mat

eria

l sur

roun

ding

bro

nchi

oles

. Dila

ted,

blo

od-f

illed

vas

cula

r an

omal

y of

unk

now

n si

gnifi

canc

e.

2B

ulla

e (t

ype

1). E

xten

sive

per

iphe

ral e

mph

ysem

atou

s ch

ange

. Min

imal

per

ivas

cula

r ly

mph

ocyt

ic in

flam

mat

ion.

Mar

ked

cent

ral a

tele

ctas

is a

nd

prom

inen

t mus

cula

r hy

pert

roph

y ar

ound

airw

ays.

Mod

erat

e pa

rtic

ulat

e fo

reig

n m

ater

ial s

urro

undi

ng b

ronc

hiol

es.

3N

o hi

stop

atho

logy

obt

aine

d.

4M

ild p

erip

hera

l em

phys

emat

ous

chan

ge. E

xten

sive

ate

lect

asis

and

mild

mus

cula

r hy

pert

roph

y ar

ound

airw

ays.

Abu

ndan

t par

ticul

ate

fore

ign

mat

eria

l.S

uper

ficia

l por

tion

of b

ulla

or

bleb

not

incl

uded

in s

ectio

n.

5B

ulla

(ty

pe 2

) w

ith lo

w c

uboi

dal e

pith

elia

l lin

ing

and

mul

tifoc

al s

moo

th m

uscl

e in

dica

ting

cont

inui

ty w

ith r

espi

rato

ry d

ucts

. Mod

erat

e pe

riphe

ral

emph

ysem

atou

s ch

ange

. Mar

ked

atel

ecta

sis.

Mod

erat

e pa

rtic

ulat

e fo

reig

n m

ater

ial s

urro

undi

ng b

ronc

hiol

es. M

oder

ate

perib

ronc

hiol

arly

mph

opla

smac

ytic

infla

mm

ator

y in

filtr

ate

and

insp

issa

ted

muc

inou

s se

cret

ion

seen

in s

ome

airw

ays.

6B

ulla

(ty

pe 1

) w

ith lo

w c

uboi

dal e

pith

elia

l lin

ing

and

mul

tifoc

al s

moo

th m

uscl

e in

dica

ting

cont

inui

ty w

ith r

espi

rato

ry d

ucts

. Mar

ked

perip

hera

lem

phys

emat

ous

chan

ge. P

leur

al th

icke

ning

. Pro

min

ent a

tele

ctas

is a

nd m

uscu

lar

hype

rtro

phy

arou

nd a

irway

s. M

oder

ate

part

icul

ate

fore

ign

mat

eria

lsu

rrou

ndin

g br

onch

iole

s.

7N

o hi

stop

atho

logy

obt

aine

d.

8B

leb

diss

ectin

g w

ithin

the

pleu

ral c

apsu

le. E

xten

sive

per

iphe

ral e

mph

ysem

atou

s ch

ange

. Ext

ensi

ve c

entr

al a

tele

ctas

is a

nd p

rom

inen

t sm

ooth

mus

cle

hype

rtro

phy

arou

nd a

irway

s. M

oder

ate

part

icul

ate

fore

ign

mat

eria

l sur

roun

ding

bro

nchi

oles

.

9E

xten

sive

per

iphe

ral e

mph

ysem

atou

s ch

ange

. Min

imal

per

ivas

cula

r ly

mph

ocyt

ic in

flam

mat

ion.

Sm

all n

umbe

r of

per

iphe

ral l

ung

foci

with

lym

phoc

ytic

infil

trat

e an

d in

ters

titia

l fib

rosi

s. M

arke

d ce

ntra

l ate

lect

asis

and

min

imal

mus

cula

r hy

pert

roph

y ar

ound

airw

ays.

Sm

all a

mou

nt o

f par

ticul

ate

fore

ign

mat

eria

l sur

roun

ding

bro

nchi

oles

. Sup

erfic

ial p

ortio

n of

bul

la o

r bl

eb n

ot in

clud

ed in

sec

tion.

10B

ulla

(ty

pe 2

) an

d bl

eb. M

arke

d pe

riphe

ral e

mph

ysem

atou

s ch

ange

. Mar

ked

pleu

ral c

apsu

le fi

bros

is a

nd in

term

itten

t int

erst

itial

fibr

osis

.M

ultif

ocal

are

as o

f ext

ensi

ve a

tele

ctas

is. S

light

am

ount

of p

artic

ulat

e fo

reig

n m

ater

ial s

urro

undi

ng b

ronc

hiol

es.

11B

ulla

(ty

pe 1

) w

ith lo

w c

uboi

dal e

pith

elia

l lin

ing

and

mul

tifoc

al s

moo

th m

uscl

e in

dica

ting

cont

inui

ty w

ith r

espi

rato

ry d

ucts

. Ext

ensi

ve p

erip

hera

lem

phys

emat

ous

chan

ge. I

ncre

ased

per

ivas

cula

r ly

mph

opla

smac

ytic

infla

mm

atio

n w

ith in

spis

sate

d m

ucou

s se

cret

ions

in s

ome

bron

chi.

Pro

min

ent

mus

cula

r hy

pert

roph

y ar

ound

airw

ays

and

cent

ral a

tele

ctas

is. I

ncre

ased

par

ticul

ate

fore

ign

mat

eria

l sur

roun

ding

bro

nchi

oles

.

12B

ulla

(ty

pe 1

) w

ith lo

w c

uboi

dal e

pith

elia

l lin

ing

and

mul

tifoc

al s

moo

th m

uscl

e in

dica

ting

cont

inui

ty w

ith r

espi

rato

ry d

ucts

. Ext

ensi

ve p

erip

hera

lem

phys

emat

ous

chan

ge. M

oder

ate

mus

cula

r hy

pert

roph

y ar

ound

airw

ays

and

exte

nsiv

e ce

ntra

l ate

lect

asis

. Mod

erat

e pa

rtic

ulat

e fo

reig

n m

ater

ial

surr

ound

ing

bron

chio

les.

persisted in all of the dogs, despite 1 to 5 days of conserva-tive treatment. Similar results were also found in two previ-ous studies where pneumothorax persisted or recurred ineight of 11 (73%) and seven of eight (88%) dogs with con-firmed or presumed blebs and bullae after treatment withthoracocentesis or thoracostomy tube drainage.2,7 Based onthese results, conservative treatment should not be consid-ered a reliable means of treating pneumothorax caused bypulmonary blebs and bullae in dogs, and surgical treatmentshould be pursued once other obvious causes of pneumo-thorax have been ruled out. For dogs in which surgicaltreatment is not an option, prolonged conservative treatmentmay eventually resolve the pneumothorax; however, thispossibility must be balanced against the extended hospital-ization time and potential complications associated withrepeated thoracocentesis or thoracostomy tube drainage.Ultimately, the decision regarding how long to pursue con-servative treatment should be based on the severity of clini-cal signs, the rate of air accumulation, the ability to rule outunderlying lung disease, and the availability of appropriatesurgical expertise and postoperative care.

Definitive treatment for dogs involves resecting the pul-monary blebs and bullae with a partial or complete lunglobectomy. A median sternotomy approach is recommendedso that the entire thorax can be explored. Lesions may bepresent on multiple lung lobes, so each lobe should be thor-oughly examined. Bleb and bulla lesions typically appear asfocal, translucent, “bubble-like” lesions on the apices of thelungs, although they may be located anywhere within thelung. Blebs and type 1 and 2 bullae may look very similardepending upon their size and location, and in most cases itis not possible to distinguish the difference between thelesions on gross inspection.6 The size, number, and locationof the lesions on each lobe will determine the amount oflung tissue that needs to be removed. For dogs with lesionsinvolving multiple lobes, it may not be possible to com-pletely resect all of the lesions without significantly reduc-ing lung capacity. For these dogs, other treatments thatpreserve lung capacity such as mechanical or chemical pleu-rodesis may be of benefit; however, these treatments havehad limited success in creating pleural adhesions in experi-mental studies, and their use for the treatment of pneumo-thorax due to blebs and bullae has not been reported.

The use of an automatic stapling device is recommendedfor partial lung lobectomy, because it is faster and results infewer complications compared to conventional suturingtechniques.11 In this study, one dog (case no. 3) experi-enced leakage of air from a staple line after partial lobec-tomy. The precise reason for the leakage was notdetermined, although it was most likely due to staples fail-ing to engage tissue properly.11 Other treatments such asmechanical and chemical pleurodesis have been describedin dogs in both experimental studies and in a small numberof clinical cases. However, these treatments have had lim-ited success in creating pleural adhesions, and their use forthe specific treatment of pneumothorax due to blebs andbullae requires further investigation.12,13

Results of surgical treatment were considered excellentfor the dogs in this study. None of the dogs developedsigns of recurrent pneumothorax due to blebs or bullae inthe follow-up period. For the one dog (case no. 3) that col-lapsed and died suddenly 36 months after surgery, thecause of death was not determined; however, sudden deathwithout prior respiratory signs would not be typical forrecurrent pneumothorax due to pulmonary blebs or bullae.Unfortunately, necropsies were not performed on any ofthe dogs, so the condition of the lungs at the time of deathwas not known.

In humans, spontaneous pneumothorax due to pul-monary blebs and bullae is typically classified as primaryspontaneous pneumothorax.4,14,15 It occurs most com-monly in young men, between 20 and 40 years of age, whohave no previous history of lung disease.6,14,16 In contrastto dogs, the pneumothorax in humans is typically unilateraland does not usually progress or result in immediate respi-ratory compromise.4,16 Clinical signs include chest pain,tachypnea, and dyspnea, although some patients may beasymptomatic or only mildly affected.4,14 As is often thecase with dogs, thoracic radiographs in humans usually donot reveal any underlying pulmonary disease as a cause ofthe pneumothorax, although rarely bulla lesions may bedetected.14,15 In cases where thoracic CT has been per-formed, blebs or bullae have been identified on the marginsof the lungs and have been described as emphysema-likechanges.15,17

Treatment for humans with primary spontaneous pneu-mothorax caused by blebs or bullae is typically conserva-tive, involving strict rest and, if necessary, thoracic drainagewith thoracocentesis or, less commonly, a thoracostomytube.14,15,18 In contrast to dogs, conservative treatment inhumans is generally successful, with minimal morbidityand recurrence rates ranging between 16% and52%.14,15,18,19 The reason for the improved results withconservative treatment in humans compared to dogs is notknown; however, it may be related to differences in thethrombolytic and fibrinolytic systems that ultimately lead toadhesion formation and the sealing of bleb or bullalesions.12

For humans that do not respond to conservative treat-ment, conventional surgical treatment is performed byresecting pulmonary blebs and bullae through a thoracot-omy incision.15,18 In humans, the average recurrence ratefor pneumothorax after conventional surgical treatment is1.5%.14,15 More recently, the use of minimally invasive,video-assisted thoracoscopic techniques has been describedfor resection of pulmonary lesions.14,15,20 The averagerecurrence rate for video-assisted thoracoscopy techniquesis slightly higher (4%), but complication rates and surgicaltimes are reduced.15 Other forms of treatment that havebeen described for bleb and bulla lesions include chemicalpleurodesis, mechanical pleurodesis, and partial pleurec-tomy, with recurrence rates ranging from 8% to 25%.15,18

The bulla lesions from the dogs in this study most closelyresembled the type 1 and type 2 bullae described in Figure

September/October 2003, Vol. 39 Pulmonary Blebs and Bullae 443

1.6 Histopathological examination revealed a consistent pat-tern of focal abnormalities, including subpleural emphysema,atelectasis, muscular hypertrophy of the respiratory ducts,increased foreign particulate matter, and varying degrees ofinflammation. Similarly, bleb and bulla lesions from humanswith primary spontaneous pneumothorax exhibit consistentfocal changes, including emphysema, atelectasis, chronicinflammation, fibrosis, increased particulate foreign material,bronchial lesions, and vascular changes, with the remainderof the lungs appearing macroscopically normal.21-23 It is notclear whether the muscular hypertrophy found surroundingthe respiratory ducts in the dogs was the cause or result ofbleb and bullae formation; however, it does suggest a chronicchange and indicates that the lesions may exist for some timebefore clinical signs develop. In addition, the fact that noobvious cause for the lesions was identified in these sectionssupports the idea that focal blebs and bullae represent a dis-tinct or “primary” disease in dogs and that they are not theresult of some other disease process.

Previous veterinary reports have suggested that there aremarked differences between the histopathological findingsfrom bleb and bulla lesions in dogs compared to thosefound in humans with primary spontaneous pneumotho-rax.2,7,9 These comments were based on the idea that bleband bulla lesions in humans had no associated pathologicalchanges and that the pathological changes associated withthe bleb and bulla lesions in dogs represented significantunderlying disease such as diffuse emphysema.2,7,9 Thesefindings were not substantiated in the authors’ study, andthe histopathological findings from these dogs clearly illus-trate the similarities with bleb and bulla lesions observed inhumans with primary spontaneous pneumothorax.21-23

The pathogenesis of pulmonary bleb and bulla lesions inboth dogs and humans is not completely understood; how-ever, the histopathological similarities between species maysuggest a similar pathogenesis. In humans, one theory sug-gests that increased distensile forces generated at the apicesof the lungs in tall individuals are responsible for bleb andbulla formation.24 Increases in transpulmonary pressureresulting from changes in atmospheric pressure have alsobeen implicated as a potential cause for formation and rup-ture of pulmonary bleb and bulla lesions.25 Cigarette smok-ing has been determined to be a significant risk factor fordeveloping pulmonary bleb and bulla lesions in humans, dueto its effect on degradative enzymes in the alveoli andincreased inflammation in the lower airways.16 One studyrevealed a 22-fold increase in relative risk for developingpneumothorax in male smokers and a nine-fold increase inrelative risk in female smokers.16 Alpha-1 antitrypsin maybe inactivated by smoking, creating a focal imbalancebetween elastase and alpha-1 antitrypsin. This results inincreased elastase-induced degradation of elastic fibers andprogressive destruction of pulmonary parenchyma.26 Smok-ing also increases the number of macrophages and neu-trophils in the distal airways. This influx of inflammatorycells may create a partial obstruction that acts as a “check-valve” leading to increased pressures in the distal air spaces,

hyperinflation of alveoli, and eventual bulla formation.4

Influx of inflammatory cells has also been associated withbronchiolitis, bronchiolar wall fibrosis, and destruction ofpulmonary parenchyma leading to the formation of emphy-sematous-like changes.27 Bronchoalveolar lavage in humanswith primary spontaneous pneumothorax has shown a closerelationship between the total cell count, especiallymacrophages, and the extent of emphysematous-likechanges seen on CT.28 Another theory suggests that theremay be anatomical differences in the lower airways that pre-dispose humans who have never smoked to spontaneouspneumothorax. A significant number of bilateral airwayanomalies, including abnormal airway branching, smallerdiameter airways, and accessory airways, have been identi-fied with bronchoscopy in humans having spontaneouspneumothorax.29

In addition to the many theories regarding the formationof bleb and bulla lesions, the actual source of pneumotho-rax and the mechanism of leakage from the bleb and bullalesions are also debatable.22 It is generally accepted thatrupture of a bleb or bulla lesion is the cause of pneumotho-rax.4,18 However, the potential for leakage of air throughthe wall of a bulla, without actual rupture, has been sug-gested by a study that examined the interior and exteriorsurfaces of type 1 to 3 bullae using scanning electronmicroscopy.22 A marked absence of mesothelial cells on theexternal surface of type 1 bullae was found, supporting thetheory that air may diffuse between mesothelial cells andthat integrity of the mesothelial cell layer may play animportant role in the pathogenesis of spontaneous pneu-mothorax.22

Further investigation into the anatomical, biochemical,inflammatory, and epidemiological aspects of spontaneouspneumothorax in dogs is needed. Prospective examinationof the histopathology of multiple areas of grossly normaland abnormal lung is necessary to further define the originand distribution of the lesions. Analysis of degradativeenzymes present in the lung parenchyma may help deter-mine if an imbalance exists that may be responsible for pro-gressive weakening of the alveolar wall and bullaformation, as has been suggested in humans. Analysis ofbronchoalveolar lavage samples from affected and unaf-fected lobes may help determine if inflammation of the dis-tal airways is present that may potentially contribute to apartial obstruction and the “check-valve” effect. Also, epi-demiological evaluation of potential risk factors such as“second-hand” smoke in the environment or chest height-to-width ratios may help identify dogs at risk for develop-ing spontaneous pneumothorax.

ConclusionPulmonary blebs and bullae are the most common cause ofspontaneous pneumothorax in dogs. The lesions should besuspected in any dog with spontaneous pneumothorax whenno other obvious source of air leakage can be identifiedfrom the history, clinical examination, or thoracic radio-graphs. Affected dogs are typically healthy, middle-aged,

444 JOURNAL of the American Animal Hospital Association September/October 2003, Vol. 39

large breeds or have deep-chested conformation, with noprevious history of lung disease. Clinical signs include vari-ous degrees of respiratory distress that may progress overseveral hours to days. Bleb and bulla lesions are not usuallyevident on thoracic radiographs; however, the use of CT orpossibly diagnostic thoracoscopy may be more helpful fordetecting small pulmonary lesions. Persistence of pneu-mothorax is common after treatment with thoracocentesisor thoracostomy drainage. Surgical treatment involves par-tial or complete lung lobectomy. A median sternotomyapproach is recommended to allow thorough examinationof all the lungs. Multiple lesions are common and are usu-ally located on the apices of the cranial lung lobes.Histopathological findings are similar to those found inhumans with primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Althoughthe pathogenesis of bleb and bulla lesions is still not com-pletely understood, the long-term outcome appears to beexcellent after surgical resection of pulmonary lesions.

a Proximate Linear Cutter, 30-mm stapler; Ethicon Endosurgery, Inc.,Edinburgh, Scotland

b Numorph; Evans Medical Ltd, Slough, Berkshire, Englandc Marcaine; Astra Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Kings Langley, England

References11. Orton EC, ed. Small animal thoracic surgery. Philadelphia: Lea &

Febiger, 1995:107-113.12. Valentine A, Smeak D, Allen D, Mauterer J, Minihan A. Spontaneous

pneumothorax in dogs. Comp Cont Ed Pract Vet 1996;18:53-62.13. Yoshioka MM. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax in twelve

dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1982;18:57-62.14. O’Neill S. Spontaneous pneumothorax: aetiology, management and

complications. Ir Med J 1987;80:306-311.15. Tanaka F, Itoh M, Esaki H, Isobe J, Ueno Y, Inoue R. Secondary spon-

taneous pneumothorax. Ann Thor Surg 1993;55:372-376.16. Murphy DM, Fishman AP. Bullous disease of the lung. Pulmonary

diseases and disorders. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988:1219-2793.

17. Holtsinger RH, Beale BS, Bellah JR, King RR. Spontaneous pneu-mothorax in the dog: a retrospective analysis of 21 cases. J Am AnimHosp Assoc 1993;29:195-210.

18. Puerto DA, Brockman DJ, Lindquist C, Drobatz K. Surgical and non-surgical management of and selected risk factors for spontaneouspneumothorax in dogs: 64 cases (1986-1999). J Am Vet Med Assoc2002;220:1670-1674.

19. Kramek BA, Caywood DD, O’Brien TD. Bullous emphysema andrecurrent pneumothorax in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc1985;186:971-974.

10. Shamji F. Classification of cystic and bullous lung disease. Chest SurgClin North Am 1995;5:701-716.

11. LaRue SM, Withrow SJ, Wykes PM. Lung resection using surgicalstaples in dogs and cats. Vet Surg 1987;16:238-240.

12. Jerram RM, Fossum TW, Berridge BR, Steinheimer DN, Slatter MR.The efficacy of mechanical abrasion and talc slurry as methods ofpleurodesis in normal dogs. Vet Surg 1999;28:322-332.

13. Birchard SJ, Gallagher L. Use pleurodesis in treating selected pleuraldiseases. Comp Cont Ed Pract Vet 1988;10:826-832.

14. Sahn SA, Heffner JE. Spontaneous pneumothorax. N Engl J Med2000;342:868-874.

15. Schramel FMNH, Postmus PE, Vanderschueren RGJRA. Currentaspects of spontaneous pneumothorax. Eur Resp J 1997;10:1372-1379.

16. Bense L, Eklund G, Odont D, Wiman LG. Smoking and theincreased risk of contracting spontaneous pneumothorax. Chest1987;92:1009-1012.

17. Lesur O, Delorme N, Fromaget JM, Bernadac P, Polu JM. Computedtomography in the etiologic assessment of idiopathic spontaneouspneumothorax. Chest 1990;98:341-347.

18. Sassoon CSH. The aetiology and treatment of spontaneous pneumo-thorax. Curr Opin Pulmon Med 1995;1:331-338.

19. Sadikot RT, Greene T, Meadows K, Arnold AG. Recurrence of pri-mary spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorax 1997;52:805-809.

20. DeGiamocco T, Rendina EA, Venuta F, Ciriaco P, Lena A, Ricci C.Video-assisted thoracoscopy in the management of recurrent sponta-neous pneumothorax. Eur J Surg 1995;161:227-230.

21. Lichter I, Gwynne JF. Spontaneous pneumothorax in young subjects,a clinical and pathological study. Thorax 1971;26:409-417.

22. Ohata M, Suzuki H. Pathogenesis of spontaneous pneumothorax, withspecial reference to the ultrastructure of emphysematous bullae. Chest1980;77:771-777.

23. Taki T, Hatakenaka R, Kuwabara M, Matsubara Y, Nagase C, Ikeda S.Surgical treatment of the spontaneous pneumothoraces and its patho-logical findings. Communication presented at XXVI Congress ofA.I.B.P., Florence 1977:296-306.

24. Vawter DL, Matthews FL, West JB. Effect of shape and size of lungand chest wall on stresses in the lung. J Applied Phys 1975;39:9-17.

25. Scott GC, Berger R, McKean HE. The role of atmospheric pressurevariation in the development of spontaneous pneumothoraces. AmRev Resp Dis 1989;139:659-662.

26. Fukuda Y, Haraguchi S, Tanaka S, Yamanaka N. Pathogenesis of blebsand bullae of patients with spontaneous pneumothorax: an ultrastruc-tural and immunohistochemical study. Am J Resp Crit Care Med1994;149:A1022.

27. Adenisa AM, Vallyathan V, McQuillen EN, Weaver SO, Craighead JE.Bronchiolar inflammation and fibrosis associated with smoking: amorphologic cross-sectional population analysis. Am Rev Resp Dis1991;143:144-149.

28. Schramel FMNH, Meyer CJLM, Postmus PE. Inflammation as acause of spontaneous pneumothorax and emphysematous-likechanges: results of bronchoalveolar lavage. Eur Resp J 1995;8(suppl 19):397-402.

29. Bense L, Eklund G, Winan LG. Bilateral bronchial anomaly. A patho-genic factor in spontaneous pneumothorax. Am Rev Resp Dis1992;146:513-516.

September/October 2003, Vol. 39 Pulmonary Blebs and Bullae 445