Skull Base fractures

Transcript of Skull Base fractures

Basilar Skull Fractures Leonel Martinez, M.D.

Faculty Advisor: Farrah Siddiqui, M.D. The University of Texas Medical Branch

Department of Otolaryngology Grand Rounds Presentation

December 11, 2013

http://vi.sualize.us/tumblr_blood_pography_head_paint_picture_2qxb.html

Incidence- overall

Anatomy- Each section

Evaluation

Management

Objectives

No drugs will cure skull base fractures.

I do not own stock in medical equipment.

However, I do drive a car, own a baseball bat and work at the TDC hospital.

Disclosure for CME

In US, 2 million head injuries occur yearly.

Leading cause of death and disability of children.

Motor vehicle accidents are leading cause of head trauma in industrialized countries.

Up to 1/3 of motor vehicle injuries involve head and neck injuries and 28% of all fractures of involving MVA are of the head and neck region.

Incidence

cElhaney JH, Hopper RH Jr, Nightingale RW, Myers BS. Mechanisms of basilar skull fracture. J Neurotrauma. 1995 Aug;12(4):669-78. PubMed PMID: 8683618.

Skull base fractures occur in 3.5-24 % of head injuries.

Traumatic Coma Data Bank states 25% of severe head injuries

Incidence

Eisenberg, Howard M., et al. "Initial CT findings in 753 patients with severe head injury: a report from the NIH Traumatic Coma Data Bank.” Journal of neurosurgery 73.5 (1990): 688-698.

http://www.nelsonbarry.com/car-accident/what-are-the-5-most-common-car-accident-injuries-in-san-francisco/

They account for 2% of all traumas

Behbahani 2013- Retrospective study 1606 pt. in Tuscon.

Incidence

Skull base fracture incidence is increased with orbital wall/rim fractures (36%) and ZMC Fractures (29.9%).

Infrequent with nasal bone (7.7%) and mandible fractures (4.0%).

The incidence of skull base fracture was directly associated with the number of facial fractures per patient; one facial fracture (21.0%), two facial fractures (30.4%), and three or more facial fractures (33.3%).

Temporal bone fractures are associated 18-40% of the time.

Frontal sinus fractures occur 15-20% of the time.

Incidence with other fracture(s)

Slupchynskyj, O. S., Berkower, A. S., Byrne, D. W. and Cayten, C. G. (1992), Association of skull base and facial fractures. The Laryngoscope, 102: 1247–1250 Temporal bone fracture: evaluation and management in the modern era. Johnson F - Otolaryngol Clin North Am - 01-JUN-2008; 41(3): 597-618 Gerbino G, Roccia F, Benech A, Caldarelli C. Analysis of 158 frontal sinus fractures: current surgical management and complications. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000;28:133–139.

Anatomy

Examination of the skull and brain: method of removing the brain after it is severed from the body Henry W. Cattell, 1903

Anatomy

Anatomy

https://www2.aofoundation.org/wps/portal/!ut/p/c0/04_SB8K8xLLM9MSSzPy8xBz9CP0os3hng7BARydDRwN3QwMDA08zTzdvvxBjI wN_I_2CbEdFADiM_QM!/?segment=Cranium&bone=CMF&classification=93-Skull%20base%2C%20Skull%20base%20fractures&teaserTitle= &showPage=diagnosis&contentUrl=/srg/93/01-Diagnosis/skull_base-skull_base.jsp

Anatomy

https://www2.aofoundation.org/wps/portal/!ut/p/c0/04_SB8K8xLLM9MSSzPy8xBz9CP0os3hng7BARydDRwN3QwMDA08zTzdvvxBjI wN_I_2CbEdFADiM_QM!/?segment=Cranium&bone=CMF&classification=93-Skull%20base%2C%20Skull%20base%20fractures&teaserTitle= &showPage=diagnosis&contentUrl=/srg/93/01-Diagnosis/skull_base-skull_base.jsp

Anatomy

Base of skull: above,” ©2012 Icon Learning Systems, Plate # [11]. Netter Images. Used under NEOMED License. Accessed on [12-11-2013].

Anatomy

Anatomy

Base of skull: above,” ©2012 Icon Learning Systems, Plate # [11]. Netter Images. Used under NEOMED License. Accessed on [12-11-2013].

Anatomy

Anatomy

Base of skull: above,” ©2012 Icon Learning Systems, Plate # [11]. Netter Images. Used under NEOMED License. Accessed on [12-11-2013].

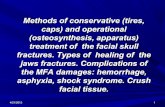

Anatomy: Fractures

Anatomy: Fractures

Anatomy: Fractures

Anatomy: Fractures

RK Jackler Atlas of Skull Base Surgery and Neurotology 2009

This includes posterior frontal sinus, roof of ethmoid, cribriform and orbital roof.

Classification (Damianos):

Type 1- Cribriform fractures- linear through cribriform.

Type 2- Frontoethmoid fracture- Ethmoids and medial frontal sinus walls.

Type 3- Lateral frontal fracture- Through the lateral frontal sinus to the superomedial wall of orbit.

Type 4- Mixed- any combination of above.

Anatomy: Anterior Skull Base Fractures

Damianos SA, David BJ, Ameen AA, et al. Compound anterior cranial base fractures: classification using computerized tomography scanning as a basis for selection of patients for dural repair. J Neurosurg 1998;88:471-477

Anatomy: Anterior Skull Base Fractures Type I Fractures

Damianos SA, David BJ, Ameen AA, et al. Compound anterior cranial base fractures: classification using computerized tomography scanning as a basis for selection of patients for dural repair. J Neurosurg 1998;88:471-477

Anatomy: Anterior Skull Base Fractures

Type II fractures

Damianos SA, David BJ, Ameen AA, et al. Compound anterior cranial base fractures: classification using computerized tomography scanning as a basis for selection of patients for dural repair. J Neurosurg 1998;88:471-477

Anatomy: Anterior Skull Base Fractures

Type III fractures

Damianos SA, David BJ, Ameen AA, et al. Compound anterior cranial base fractures: classification using computerized tomography scanning as a basis for selection of patients for dural repair. J Neurosurg 1998;88:471-477

Anatomy: Middle Skull Base

Anatomy: Middle Skull Base: Temporal Bone

Anatomy: Middle Skull Base: Temporal Bone

Anatomy: Middle Skull Base: Temporal Bone

Collins JM, Krishnamoorthy AK, Kubal WS, Johnson MH, Poon CS. Multidetector CT of temporal bone fractures. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2012 Oct;33(5):418-31

Anatomy: Middle Skull Base: Temporal Bone

Collins JM, Krishnamoorthy AK, Kubal WS, Johnson MH, Poon CS. Multidetector CT of temporal bone fractures. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2012 Oct;33(5):418-31

2011-Kang-Seoul 128 patients 2003-2010.

Hearing loss noted 78 pt.

9 otic violating- with 8 (88.9%) having SNHL.

68 otic sparing- with 18 (26.1%) having SNHL.

Anatomy: Middle Skull Base: Temporal Bone

Kang HM, Kim MG, Boo SH, Kim KH, Yeo EK, Lee SK, Yeo SG. Comparison of the clinical relevance of traditional and new classification systems of temporal bone fractures. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Aug;269(8):1893-9

Little and Kesser 2006- Showed 5 fold increase in facial nerve injury, 25 fold increase in SNHL and 8 fold increase in CSF leaks with otic capsule violating fractures.

They also showed a correlation among OCV fracture and facial nerve paresis or paralysis, In a large series of 820 temporal bone fractures facial nerve paralysis occurred in 48% of OCV fractures versus only 6% in OCS fractures.

The incidence of otic capsule violating fracture is 2.5% to 5.6%.

Anatomy: Middle Skull Base: Temporal Bone

Uncommon, 9/25000 (0.39%) recorded in one case series over 5 years.

All patients had cranial nerve defects (II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VII), with VI and VII most common (66%).

Longitudinal fractures have worse prognosis, with 3 out of 5 patients died from verebrobasilar injury.

Transverse had 1 out of 4 die from carotid artery injury.

Posterior Fossa: Clivus fractures

Clivus fractures: clinical presentations and courses Neurosurg Rev (2004) 27:194–198 DOI 10.1007/s10143-004-0320-

Posterior Fossa: Clivus fractures

Clivus fractures: clinical presentations and courses Neurosurg Rev (2004) 27:194–198

DOI 10.1007/s10143-004-0320-2

Posterior Fossa: Clivus fractures

Clivus fractures: clinical presentations and courses Neurosurg Rev (2004) 27:194–198

DOI 10.1007/s10143-004-0320-2

High energy blunt trauma with compression, rotational or lateral bending injuries to head.

Type I- Axial compression with comminution of occipital condyle-stable injury with no displacement.

Type II- Direct blow that occurs with skull base and occipital condyle- intact alar ligaments.

Type III- Avulsion with lateral or rotational forces with torn alar ligaments and fractures.

Posterior Fossa: Occipital condylar fracture

Posterior Fossa: Occipital condylar fracture

Posterior Fossa: Occipital condylar fracture

Posterior Fossa: Occipital condylar fracture

Evaluation

http://www.missmassacre.net/?p=2460

Periorbital ecchymosis (raccoon eyes) Conjunctival hemorrhage Anosmia Mastoid ecchymosis (Battles sign) Vision changes CSF rhinorrhea or otorrhea Step off of supraorbital ridge Hearing loss Facial paralysis Facial numbness

Physical Exam

Frontal bone fractures had the most clinical signs.

Battle’s sign (100%) and unilateral Periorbital ecchymosis (90%), bloody otorrhea (70%) are highest predictive value for skull base fracture.

Patients with GCS of 13-15, PPV for intracranial lesions was (78%) periorbital ecchymosis, (66%) Battle’s sign and (41%) bloody otorrhea.

Clinical signs

Positive predictive values of selected clinical signs associated with skull base fractures. (PMID:11105835) Pretto Flores L, De Almeida CS, Casulari LA Journal of Neurosurgical Sciences [2000, 44(2):77-82; discussion 82-3]

Periorbital Ecchymosis

http://rlbatesmd.blogspot.com/2010/07/blepharoplasty-complications-article.html

Battle sign - Think Basilar Skull Fracture

Battle sign

http://www.dooey.net/OMFS/

CSF Rhinorrhea

http://amandela.sg/a-runny-nose-may-not-just-be-a-runny-nose/

Eighty percent of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks occur following nonsurgical trauma (16% surgical).

Occur in 2% of all head traumas, and 12% to 30% of all basilar skull fractures, M>F.

50% appear in first 2 days, 70% in one week, and almost all seen in 3 months.

CSF Rhinorrhea

CSF Rhinorrhea

REtRoSPECtivE StuDY oF SKuLL BASE FRACtuRE: A StuDY oF iNCiDENtS, ComPLiCAtioNS, mANAgEmENt, AND outComE ovERviEW FRom tRAumA-oNE-LEvEL iNStitutE ovER FivE YEARS – Michael lemole, Md, Mandana Behbahani, Ba (presenter), university of arizona college of Medicine

Cranial nerve injuries

http://kevinpremed.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/cranial-nerves.jpg

CN I- anosmia- from anterior fossa injuries (cribriform). Sense of smell may return over several months. Workup is limited with CT scan.

CN II- Blindness worst outcome- from damage to the optic canal or orbit. Sphenoid body with sella turcica damage can cause injury to the optic chiasm, causing bitemporal blindness.

Cranial nerve injuries: Anterior Cranial Fossa

Gjerris F. Traumatic lesions of the visual pathways. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, eds. Handbook of Neurology. Vol 24. New York: Elsevier; 1976:27–57. Kline LB, Morawetz RB, Swaid SN. Indirect injury of the optic nerve. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:756–764.

CN III- Diplopia, impaired EOM.

Noted dilated pupil, inability to move eye medially, superiorly, or inferiorly (down and out). Usually from direct frontal blow, which stretches the nerve at the posterior cavernous sinus as it enters the brain.

Treatment consists of wearing a patch over the affected eye, as spontaneous recovery usually occurs in 4-6 weeks.

Cranial nerve injuries: Middle Cranial Fossa

Gjerris F. Traumatic lesions of the visual pathways. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, eds. Handbook of Neurology. Vol 24. New York: Elsevier; 1976:27–57. Kline LB, Morawetz RB, Swaid SN. Indirect injury of the optic nerve. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:756–764.

CN IV- diplopia-

Least common injury site. Cause from stretching of nerve as it exits from the dorsal midbrain.

Treatment same as CN III, with patch and spontaneous recovery.

CN V- Sensory deficits to the face. V1-supraorbital, V2- maxillary, V3-mandibular.

V1 most commonly damaged portion, with injury at supraorbital notch.

Cranial nerve injuries: Middle Cranial Fossa

CN VI- diplopia. Damage to the clivus. Also stretched or avulsed when leaving the pons. Unable to abduct. Conservative treatment with spontaneous recovery.

Superior orbital fissure fractures can damage CN III, IV, VI and V1- known as superior orbital fissure syndrome. When accompanied by blindness, it is known as orbital apex syndrome and involves optic foramen.

Cranial nerve injuries: Middle Cranial Fossa

Gjerris F. Traumatic lesions of the visual pathways. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, eds. Handbook of Neurology. Vol 24. New York: Elsevier; 1976:27–57. Kline LB, Morawetz RB, Swaid SN. Indirect injury of the optic nerve. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:756–764.

CN VII- facial paralysis. Most common temporal bone, 50% of transverse and 25% of longitudinal fractures as injuries. ENoG of 90% denervation should undergo surgery.

CN VIII- Hearing loss, vestibular damage. Cochlear and vestibular nerve damage, or damage to otic capsule can lead to total degeneration with deafness and labyrinthine dysfunction. Workup with Audiogram, ABR, and ENG. Cochlear implants have 84% success rate of return to speech understanding.

Cranial nerve injuries: Middle Cranial Fossa

Gjerris F. Traumatic lesions of the visual pathways. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, eds. Handbook of Neurology. Vol 24. New York: Elsevier; 1976:27–57. Kline LB, Morawetz RB, Swaid SN. Indirect injury of the optic nerve. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:756–764.

CN IX, X, XI- exit out of jugular foramen and CN XII exit out of hypoglossal foramen.

Glossopharyngeal injury leads to dysphagia and loss of gag

Vagus nerve results in ipsilateral cord or palate weakness with hoarseness.

Spinal accessory nerve causes weakness with head rotation and shoulder elevation. Hypoglossal nerve injury causes atrophy of ipsilateral tongue.

Treatment is usually supportive with therapy.

Cranial nerve injuries: Posterior Cranial Fossa

Gjerris F. Traumatic lesions of the visual pathways. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, eds. Handbook of Neurology. Vol 24. New York: Elsevier; 1976:27–57. Kline LB, Morawetz RB, Swaid SN. Indirect injury of the optic nerve. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:756–764.

New Orleans criteria

CT required for minor head trauma (Loss of consciousness with normal neurologic exam) if the following apply:

Headache, vomit, >60 yo, Drug/alcohol, seizure witness, anterograde amnesia, soft tissue injury

Evaluation: Imaging

Smits M, Dippel DW, de Haan GG, Dekker HM, Vos PE, Kool DR, Nederkoorn PJ, Hofman PA, Twijnstra A, Tanghe HL, Hunink MG. External validation of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria for CT scanning in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005 Sep 28;294(12):1519-25. PubMed PMID: 16189365.

X-Ray skull: Not recommended; delays diagnosis of intracranial injury.

It is not recommended for most head traumas. It has some benefit for non accidental trauma in children.

Evaluation: Imaging

hornbury JR, Masters SJ, Campbell JA. Imaging recommendations for head trauma: a new comprehensive strategy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. Oct 1987;149(4):781-3

HRCT scan is the gold standard for skull base injury. It has the best modality to evaluate bony fractures.

The slices should be 1-1.5 mm thick at the most.

Helical CT scans are useful in the evaluation of occipital condylar fractures.

CT Angiography is an excellent, quick, non-invasive technique for the assessment of cerebral vasculature.

Evaluation: Imaging: CT

Evaluation: Imaging: CT

http://www.jaypeejournals.com/eJournals/ShowText.aspx?ID=3093&Type=FREE&TYP=TOP&IN=_eJournals/images/JPLOGO.gif&IID=238&isPDF=NO

Imaging: CT

Imaging: CT

Textbook of Head Injury Raj Kumar, A. K. Mahapatra JP Medical Ltd, 2012 - Medical - 320 pages

Imaging: CT

Multidetector CT of Temporal Bone Fractures John M. Collins, Aswin K. Krishnamoorthy, Wayne S. Kubal, Michele H. Johnson , Colin S. Poon Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR 1 October 2012 (volume 33 issue 5 Pages 418-431

Imaging: CT

Multidetector CT of Temporal Bone Fractures John M. Collins, Aswin K. Krishnamoorthy, Wayne S. Kubal, Michele H. Johnson , Colin S. Poon Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR 1 October 2012 (volume 33 issue 5 Pages 418-431

Imaging: CT

Multidetector CT of Temporal Bone Fractures John M. Collins, Aswin K. Krishnamoorthy, Wayne S. Kubal, Michele H. Johnson , Colin S. Poon Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR 1 October 2012 (volume 33 issue 5 Pages 418-431

Approximately 50% of patients with skull base fractures present with delayed ischemic brain damage. Carotid injuries include carotid disruption, compression by fracture fragments or associated hematoma, arterial wall contusion or hematoma, arterial dissection, carotid cavernous fistula, and occlusion.

Behbahani 2013- Retrospective study 1606 pt. in Tuscan, 16 patients had fractures extending to carotid canal, but no carotid injures noted on angiographic studies.

Evaluation: Vascular injuries

Samii M, Tatagiba M. Skull base trauma: diagnosis and management. Neurol Res 2002;24:147-156

Biffl et all (1999)

A total of 249 patients underwent arteriography; 85 (34%) had injuries.

Independent predictors of carotid arterial injury were: Glasgow coma score ≤6, petrous bone fracture, diffuse axonal brain injury, and LeFort II or III fracture. Having one of these factors in the setting of a high-risk mechanism was associated with 41% risk of injury.

Evaluation: Vascular injuries

Biffl WL, Moore EE, Offner PJ, Brega KE, Franciose RJ, Elliott JP, Burch JM. Optimizing screening for blunt cerebrovascular injuries. Am J Surg. 1999

Evaluation: Vascular injuries

Sliker CW. Blunt cerebrovascular injuries: imaging with multidetector CT angiography. RadioGraphics 2008;28(6):1689–1708; discussion 1709–1710

Evaluation: Vascular injuries

Provides greater soft tissue detail but less bony detail compared to CT.

FSE T-1 or T-2 with post contrast enhancement are preferred methods to evaluate skull base.

T-2 fat suppression with image reversal is used to highlight CSF.

T2 weighted thin sliced images (FIESTA) is used to evaluate cranial nerves.

Imaging: MRI

Skull Base, Orbits, Temporal Bone, and Cranial Nerves: Anatomy on MR Imaging Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 19 (2011) 439–456doi:10.1016/j.mric.2011.05.006

Imaging: MRI

CSF evaluation

Halo or Ring Sign Bloody CSF placed on a piece of filter paper Blood will separate out from the CSF (central blood

with clear ring). The ring sign is not specific to bloody CSF Blood mixed with water, saline, and other mucus will

also produce a ring sign.

Evaluation: CSF Rhinorrhea/Otorrhea

Dula, DJ, MD and Fales, F, MD. The 'Ring Sign': Is It a Reliable Indicator for Cerebral Spinal Fluid? Annals of Emergency Medicine, 1993;22:718-720

Evaluation: CSF Rhinorrhea/Otorrhea

Beta-2-transferrin Protein produced by enzymes only in CNS.

Test requires 0.5cc of fluid. Highly sensitive and specific for CSF.

Beta-trace protein Found in CSF, heart, and serum. Not routinely ordered as it may be altered in many cases.

○ Elevated with renal insufficiency, multiple sclerosis, cerebral infarctions, and some CNS tumors.

Evaluation: CSF Rhinorrhea/Otorrhea

Moyer, P. Beta-Trace Protein Shows Promise as a Marker for Diagnosing CSF Leaks. Doctor’s Guide. Online[Available]: http://www.docguide.com/dg.nsf/PrintPrint/5DF097A1EB04B3FA85256C3E00731E65, 2002

Useful in detection of CSF leaks.

Involve intrathecal administration of radiopaque contrast (metrizamide, iohexol, or iopamido) followed by CT scan.

Up to 80% sensitivity.

However results vary with intermittent leaks, and contrast may obscure visualization of leak site.

Imaging: CT cisternograms

Meco C, Oberascher G, Arrer E, et al. Beta-trace protein test: new guidelines for the reliable diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129:508–17

CSF Rhinorrhea

CSF Rhinorrhea

http://www.chatrath.com/featuredcases.html

CSF Rhinorrhea

Treatment begins with conservative management of strict bed rest, HOB >30 degrees, no cough, sneezing, straining.

Currently, after two separate meta-analysis showed conflicting data, a Cochrane review was done for evaluation of prophylactic antibiotics for CSF leaks.

The analysis concluded that the evidence does not support the use of prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the risk of meningitis in patients with basilar skull fractures or basilar skull fractures with active CSF leak.

CSF Rhinorrhea

Ratilal BO, Costa J, Sampaio C. Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing meningitis in patients with basilar skull fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1): CD004884.

Conservative management for 7 days has resolutions rate of 85%.

Continued leakage is then treated with lumbar drainage of 10 ml/hr. This increases resolution rate to 90%.

Therefore, surgical intervention is reserved for patients who do not resolve with the above measures.

CSF Rhinorrhea

Bell RB, Dierks EJ, Homer L, et al. Management of cerebrospinal fluid leak associated with craniomaxillofacial trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;62(6):676–84.

Skull base injuries offer complex fractures that require thorough evaluations.

Division in 3 cranial vaults provides a reasonable way for evaluation.

Radiographic evaluation is important, along with history and physical exam.

Treatment measure typically begin with conservative treatment, with surgical intervention saved for severe or persistent disease.

Conclusion

Slupchynskyj, O. S., Berkower, A. S., Byrne, D. W. and Cayten, C. G. (1992), Association of skull base and facial fractures. The Laryngoscope, 102: 1247–1250

Eisenberg, Howard M., et al. "Initial CT findings in 753 patients with severe head injury: a report from the NIH Traumatic Coma Data Bank." Journal of neurosurgery 73.5 (1990): 688-698.

http://www.nelsonbarry.com/car-accident/what-are-the-5-most-common-car-accident-injuries-in-san-francisco/ Positive predictive values of selected clinical signs associated with skull base fractures. (PMID:11105835) Pretto Flores L, De Almeida CS, Casulari LA

Journal of Neurosurgical Sciences [2000, 44(2):77-82; discussion 82-3] http://rlbatesmd.blogspot.com/2010/07/blepharoplasty-complications-article.html https://www2.aofoundation.org/wps/portal/!ut/p/c0/04_SB8K8xLLM9MSSzPy8xBz9CP0os3hng7BARydDRwN3QwMD

A08zTzdvvxBjIwN_I_2CbEdFADiM_QM!/?segment=Cranium&bone=CMF&classification=93-Skull%20base%2C%20Skull%20base%20fractures&teaserTitle=&showPage=diagnosis&contentUrl=/srg/93/01-Diagnosis/skull_base-skull_base.jsp

Textbook of Head Injury Raj Kumar, A. K. Mahapatra JP Medical Ltd, 2012 - Medical - 320 pages Driscoll CL, Lane JI. Advances in skull base imaging. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2007 Jun;40(3) cElhaney JH, Hopper RH Jr, Nightingale RW, Myers BS. Mechanisms of basilar skull fracture. J Neurotrauma. 1995

Aug;12(4):669-78. PubMed PMID: 8683618.:439-54, vii. Review. PubMed PMID: 17544690. http://www.lhsc.on.ca/Health_Professionals/CCTC/edubriefs/baseskull.htm Gjerris F. Traumatic lesions of the visual pathways. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, eds. Handbook of Neurology. Vol 24. New

York: Elsevier; 1976:27–57. Base of skull: above,” ©2012 Icon Learning Systems, Plate # [11]. Netter Images. Used under NEOMED License.

Accessed on [12-11-2013]. Kline LB, Morawetz RB, Swaid SN. Indirect injury of the optic nerve. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:756–764.

References

Temporal bone fracture: evaluation and management in the modern era. Johnson F - Otolaryngol Clin North Am - 01-JUN-2008; 41(3): 597-618

Gerbino G, Roccia F, Benech A, Caldarelli C. Analysis of 158 frontal sinus fractures: current surgical management and complications. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000;28:133–139.

REtRoSPECtivE StuDY oF SKuLL BASE FRACtuRE: A StuDY oF iNCiDENtS, ComPLiCAtioNS, mANAgEmENt, AND outComE ovERviEW FRom tRAumA-oNE-LEvEL iNStitutE ovER FivE YEARS – Michael lemole, Md, Mandana Behbahani, Ba (presenter), university of arizona college of Medicine

Little SC, Kesser BW. Radiographic classification of temporal bone fractures: clinical predictability using a new system. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;132(12):1300–4

Sliker CW. Blunt cerebrovascular injuries: imaging with multidetector CT angiography. RadioGraphics

2008;28(6):1689–1708; discussion 1709–1710

Kang HM, Kim MG, Boo SH, Kim KH, Yeo EK, Lee SK, Yeo SG. Comparison of the clinical relevance of traditional and new classification systems of temporal bone fractures. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Aug;269(8):1893-9

Multidetector CT of Temporal Bone Fractures John M. Collins, Aswin K. Krishnamoorthy, Wayne S. Kubal, Michele H. Johnson, Colin S. Poon Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR 1 October 2012 (volume 33 issue 5 Pages 418-431

The analysis concluded that the evidence does not support the use of

prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the risk of meningitis in patients with basilar skull

fractures or basilar skull fractures with active CSF leak

Bell RB, Dierks EJ, Homer L, et al. Management of cerebrospinal fluid leak associated

with craniomaxillofacial trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;62(6):676–84.

References