Russian Navy's Regeneration Plans[1]

-

Upload

daniel-besson -

Category

Documents

-

view

533 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Russian Navy's Regeneration Plans[1]

![Page 1: Russian Navy's Regeneration Plans[1]](https://reader035.fdocuments.net/reader035/viewer/2022073014/553d90db4a79593c328b46c5/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

Russian navy's regeneration plans Receive Strategic Comments by Email

IISS Membership Strategic Comments Homepage

Editor: Alexander Nicoll

Assistant Editor: Jessica Delaney

__________________

Recent Strategic Comments

The OSCE's uncertain future

Stuxnet: targeting Iran's nuclear programme

China's J-20: future rival for air dominance?

WikiLeaks: the price of sharing data

North Korea's uranium programme heightens concern

__________________

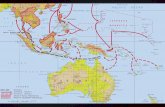

Map: Russia's military districts and fleet HQs

__________________

IISS Voices - End in sight for KC-X aircraft saga?

By Douglas Barrie, Senior Fellow for Military Aerospace

The United States Air Force is hoping to finally bring down the curtain on a long-running drama by the end of this month, as it prepares to announce who gets the contract to replace its ageing KC-135 tanker aircraft. The last competition, in 2008, was a case of winner takes nothing.

A recent deal under which Russia will buy four Mistral naval ships from France is an important

demonstration that Moscow is getting serious about building a modern navy. The first two landing

helicopter docks (LHDs) will be constructed in France and, in a significant boost to the Russian

shipbuilding industry, the other two will be built under licence in Russia. Agreed on 25 January, the deal

will mark the first time that a Western country has transferred any major weapons platform to Russia since

the end of the Second World War. However, it remains unclear whether it will kick-start a new phase of

modernisation, and whether the large-scale reform envisaged in Russia’s State Programme of Armaments

2011–2020 can be realised.

Boost to Russian industry

The agreement has wide-ranging implications for industry, for foreign aspirations to participate in the

Russian market, for military capabilities and for Russia’s longer-term modernisation plans.

It will have a considerable impact on Russia's currently stagnant shipbuilding industry. The purchase of the

Mistral in effect represents an admission that the industry lacks the technical expertise and capacity to

build such complex ships. In February, Chief of the General Staff General Nikolay Makarov admitted that it

would have taken Russian yards at least a decade to build a similar ship. However, they will play a

significant role in the Mistral deal. The first two ships will be built at the St Nazaire shipyard of STX Europe,

a subsidiary of a Korean shipbuilder which has acquired several European commercial shipyards. It will

execute the contract jointly with DCNS, the majority state-owned French naval shipbuilder. But a significant

portion of the components will be manufactured in Russia: 20% for the first and 40% for the second. The

remaining two ships will be built at a specially constructed shipyard on St Petersburg's Kotlin Island by

state-owned United Shipbuilding Corporation, with 80% of the manufacturing being of Russian origin.

Though the cost is not known, estimates suggest a price of approximately €400 million to €600m ($550m–

$820m) per boat. According to RIA Novosti, the Russian news agency, the first two ships will cost Russia a

total of €1.37 billion ($1.9bn).

This is the first time that Russia's armed forces have permitted serious foreign involvement in an otherwise

closed tendering system under which orders were previously guaranteed to be given to domestic

contractors. In light of the Mistral deal, foreign participation seems likely in future modernisation efforts.

The signature on 9 February of an agreement that will see Germany's Rheinmetall Defence build and

equip a troop-training centre in Russia was further evidence of Moscow's increased openness to foreign

competition in defence procurement. The Ministry of Defence has also confirmed that it will go ahead with

a joint enterprise with Italy's Iveco to manufacture Lynx armoured vehicles in Russia.

The injection of expertise and technology from France will aid a shipbuilding industry that has been held

back by yards that are unable to fulfil domestic and international orders. Only four new surface combatants

were launched between 2000 and 2010, all frigates and corvettes. Meanwhile, the Admiral Gorshkov

contract, which involves the refitting and conversion of a Kiev-class aircraft carrier from a short take-off and

vertical landing deck to a short take-off but arrested-recovery version for India, has suffered many

problems. A $1.5bn deal was originally signed in 2004 and delivery was scheduled for 2008. However, the

project was delayed as the scale of the conversion became apparent, and a new $2.3bn deal was signed

in 2010 for delivery to India in December 2012.

Enhanced amphibious capability

The procurement of four LHDs provides a much-needed fillip to Russia's maritime projection of air power.

The only other aircraft carrier of any sort in the navy is the Admiral Kuznetsov, a fixed- and rotary-wing

carrier that has been repeatedly laid up for repairs and seen little operational activity in its 20 years of

service. Russia has not operated any pure helicopter carriers since the Moskva-class ships were

decommissioned in the early 1990s, although the subsequent Kiev-class and the Admiral Kuznetsov-class

both mixed fixed-wing aircraft with helicopters.

The new LHDs will allow Russia to deploy up to 16 helicopters on each ship, probably including a

marinised variant of the Kamov Ka-52 Alligator attack helicopter. A Ka-52 was landed on the deck of

France's Mistral during a visit to St Petersburg in December 2009, in what now looks to have been a

prescient training exercise. Other assets that may be deployed on the Russian LHDs include anti-

submarine warfare or transport helicopters such as the Ka-27 and Ka-29 Helix.

![Page 2: Russian Navy's Regeneration Plans[1]](https://reader035.fdocuments.net/reader035/viewer/2022073014/553d90db4a79593c328b46c5/html5/thumbnails/2.jpg)

As well as helicopters, the Mistral can transport and land 60 armoured vehicles with 450 troops –

significantly more than the Ropucha- and Alligator-class landing ships in Russia's current fleet. The Mistral

will be the only vessel in active service with the Russian navy with a well deck. Currently, all vehicles

aboard Russia's amphibious vessels are loaded and unloaded via stern or bow doors, meaning the ship

has to approach within metres of the shoreline and expose itself to enemy fire. A well deck, on the other

hand, allows the disembarkation of troops and vehicles aboard smaller landing craft from over the horizon,

minimising the ship's vulnerability to missile strikes. It also allows for amphibious landings on more difficult

terrain, as the vessels that must approach the shoreline are much smaller.

Deployments subject to international scrutiny

Given this significant improvement in Russia's amphibious capability, the Mistral deal has raised concerns

among Russia's neighbours on the Black and Baltic Seas that the LHDs could be used in a conflict against

them. During the 2008 war with Georgia, Russia's Black Sea Fleet was able to blockade Poti and launch

an amphibious landing in Abkhazia involving several hundred naval infantry soldiers.

Washington is similarly concerned about the deal. In a November 2009 State Department cable published

via the WikiLeaks website, United States Ambassador to Georgia John R. Bass noted a request from the

Georgian foreign minister 'that the US push back against this sale'. According to another leaked cable, US

Secretary of Defense Robert Gates 'raised US concerns over the sale of a Mistral class helicopter carrier

to Russia' in a meeting with his French counterpart in Paris in February 2010.

But in a likely bid to assuage international concerns and particularly those of its neighbours, Moscow has

indicated that it will deploy the first two Mistrals to the Northern and Pacific Fleets (although some

conjecture remains on their destination). For the Northern Fleet vessel, the assignment suggests a focus

on projecting Russia's maritime air power in the Arctic, adding greater muscularity to its diplomatic efforts

in the disputed region, and swift access to the Atlantic should it be required. In the Pacific Fleet, the Mistral

would not only add an aerial element to any operations but would also greatly expand the fleet's

amphibious capabilities in a region that includes an unstable Korean Peninsula, a rapidly improving

Chinese navy and an ongoing dispute with Japan over the Kuril Islands. The Mistral could also have a role

to play in regional humanitarian-assistance and disaster-relief operations.

It remains open to Russia to deploy the third and fourth LHDs to the Black and Baltic Sea Fleets. Their

presence would facilitate swift deployments to crisis-hit regions, and would continue the legacy of the two

Moskva-class helicopter carriers that were deployed to the Black Sea in the 1970s and 1980s. Such a

decision would indicate the shifting priorities of Russia's navy compared to previous decades: all the Kiev-

class carriers were deployed with the Northern and Pacific Fleets, reflecting the perception of the US and

NATO as the primary threat.

However, given the dominance of Russia's armed forces over Georgia's, a Mistral seems an unnecessarily

large and capable ship for any bilateral conflict. And under a strict legal interpretation of the Montreux

Convention of 1936, the LHDs, as aircraft carriers, would not be able to enter or leave the Black Sea

through the Bosporus Strait. The Baltic would provide quicker access to the Atlantic, but the difference

would be marginal over the Northern Fleet and access would be through a narrow sea bordering several

NATO countries.

Modernisation drive

Whatever the likely future usage of the LHDs, their purchase raises the possibility that Russia's navy may

finally be emerging from a 20-year period of decline and stagnation.

Naval modernisation is an issue that has been debated extensively, particularly since the ascension to

power of Vladimir Putin. Just over a year after his inauguration as President in 2000, Putin signed the

Maritime Doctrine of the Russian Federation until the Year 2020, which highlighted the navy's role in

securing territorial sovereignty and protecting Russia's resources. The doctrine outlined a regional rather

than a global role for the navy, but greater emphasis was placed on issues such as the Arctic, territorial

disputes and undersea resources, highlighting the roles the navy could play in Russia's foreign policy.

Subsequently, two state armaments programmes (Gosudarstvennaya Programma Vooruzheniya [GPV])

have been published, detailing the defence-procurement plans of the Russian armed forces. The most

recent, the GPV 2007–2015 adopted in November 2006, allocated R5 trillion ($188bn at November 2006

exchange rate) to defence procurement over the nine-year period, with the navy supposed to build 17

surface vessels and six submarines. Even though the navy is still largely composed of Cold War-era

vessels, the government’s aspirations remain undimmed. President Dmitry Medvedev stated in March

2010 that he wished to see an annual equipment-renewal rate across the armed forces of 9–11%,

compared with the current 2%, in order to modernise 70% of military equipment by 2020.

US manufacturer Boeing came second in the two-horse race with a Northrop Grumman/EADS team and promptly appealed the decision; this was upheld, leading to the latest competitive round. Read More

__________________

Military Balance 2011

The Military Balance is

the International Institute for Strategic Studies’ annual assessment of the military capabilities and defence economics of 170 countries worldwide. It is an essential resource for those involved in security policymaking, analysis and research. The 2011 edition of the Military Balance will be launched on 8 March 2011. Order The Military Balance 2011

Order the 2011 Chart of Conflict

![Page 3: Russian Navy's Regeneration Plans[1]](https://reader035.fdocuments.net/reader035/viewer/2022073014/553d90db4a79593c328b46c5/html5/thumbnails/3.jpg)

The next GPV, which will outline defence procurement until 2020, is nearing completion. General Makarov

claimed in February 2011 that R23trn ($784.5bn) would be allocated for purchases. This is a substantial

figure, but tallies with other estimates: in September 2010 Minister of Defence Anatoly Serdyukov claimed

that the GPV 2011–2020 would have a budget of R22trn ($751bn), with R19trn ($649bn) allocated to the

Ministry of Defence and R3trn ($102bn) to other ministries. Such figures make it clear that Moscow intends

to increase procurement expenditure significantly over the coming decade.

According to Mikhail Lukanin, a correspondent for Russian newspaper Trud, of the R19trn allocated to the

Ministry of Defence, R5trn ($171bn) would go to the navy. This would be used to purchase more than 30

submarines and 42 surface combatants, representing a substantial turnover in Russia's fleet – it currently

maintains 67 submarines and 103 combat vessels of corvette size or larger. The new vessels would

include eight ballistic-missile submarines, 22 attack submarines, 12 frigates, 20 corvettes and ten landing

ships.

Lukanin's list omits any mention of a fixed-wing aircraft carrier, or the refurbishment or purchase of any

cruisers or destroyers. This may be because great uncertainty exists over such programmes, particularly a

future aircraft carrier: a statement by Medvedev in October 2008 claimed that Russian-built carriers would

be commissioned from 2013, but the GPV 2007–15 failed to mention the possibility. No carrier, cruiser or

destroyer is currently being built (though a destroyer is reportedly at the design stage), suggesting that

greater attention will be paid to smaller combatants that would prove more useful in smaller conflicts,

regional contingencies and constabulary roles such as counter-piracy. This further entrenches the shift in

Russia's naval focus, from the possibility of conflict with the US and NATO to perceived threats in East

Asia and the country's near-abroad.

Prospects for renewal

But even under favourable economic circumstances, the procurement plans to be laid out in the GPV

2011–2020 remain ambitious. The programme is expected to call for the commissioning of between eight

and ten combat vessels per year, a very tall order for a navy the size of Russia's – especially taking into

account the outdated machine tools and legacy refurbishment projects constraining its shipbuilding

capacity, as well as corruption and politicking. Problems besetting programmes such as the Bulava

submarine-launched ballistic missile also indicate challenges ahead for the navy's rebirth.

Nevertheless, by avoiding grandiose projects and facilitating overseas purchases, the GPV 2011–2020

could mark the beginning of a process of modest renewal for the navy. With various hulls already in the

water but not yet commissioned, including Borey-class ballistic-missile submarines, Yasen-class nuclear-

attack submarines, Stereguschiy- and Admiral Gorshkov-class frigates, there is likely to be a steady flow of

new vessels for the Russian navy in coming years.

Volume 17, Comment 8 – February 2011

Copyright © 2010 The International Institute For Strategic Studies

The International Institute For Strategic Studies