RSPB reserves 2012 · 2016. 10. 24. · RSPB RESERVES 2012 3 Our vision Our vision is to help...

Transcript of RSPB reserves 2012 · 2016. 10. 24. · RSPB RESERVES 2012 3 Our vision Our vision is to help...

The RSPB

UK Headquarters

The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2DL

Tel: 01767 680551

Northern Ireland Headquarters

Belvoir Park Forest, Belfast BT8 7QT

Tel: 028 9049 1547

Scotland Headquarters

2 Lochside View, Edinburgh Park, Edinburgh EH12 9DH

Tel 0131 317 4104

Wales Headquarters

Sutherland House, Castlebridge, Cowbridge Road East, Cardiff CF11 9AB

Tel: 029 2035 3000

www.rspb.org.uk

The RSPB speaks out for birds and wildlife, tackling the

problems that threaten our environment. Nature is amazing

– help us keep it that way.

As a charity, the RSPB is dependent on the goodwill and financial support

of people like you. Please visit www.rspb.org.uk/supporting or call

01767 680551 to find out more.

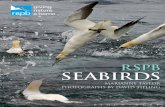

Front cover: Red-necked phalarope by Steve Knell (rspb-images.com)The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) is a registered charity: England & Walesno. 207076, Scotland no. SC037654 120-1639-11-12

I N T E R N A T I O N A LBirdLife

We belong to BirdLife International, the global

partnership of bird conservation organisations. RSPB RESERVES 2012

Abernethy

Vane Farm

Lochwinnoch

Rathlin

Belfast Lough Mersehead

Haweswater

Leighton Moss & Morecambe Bay Bempton Cliffs

Fairburn IngsBlacktoft Sands

VDearne alley – Old Moor and Bolton IngsSouth Stack Cliffs

Conwy

Freiston ShoreLake Vyrnwy

Ynys-hir Sandwell Valley

Minsmere

The Lodge

Rye Meads

Ramsey Island

Rainham Marshes

Dungeness

Radipole Lake

Arne

Titchwell Marsh

Mid Yare Valley

Lyth Valley

The Crannach

Dove Stone

Eastern Moors

Fetlar

Mousa

Sumburgh Head

North Hill

Mill Dam

Hobbister

Forsinard Flows

Culbin Sands

Loch Ruthven

Insh Marshes

Fowlsheugh

Loch of KinnordyGlenborrodale

Inversnaid

Loch Gruinart/Ardnave

The Oa

Lough Foyle

Portmore LoughLower Lough Erne Islands

Baron’s Haugh

Coquet IslandAilsa Craig

Hodbarrow

Marshside

Exe Estuary

Hayle Estuary

Mawddach Woodlands

Valley Wetlands

Marazion Marsh

Frampton Marsh

Ken-Dee Marshes

St Bees Head

Campfield Marsh

Mull of Galloway & Scar Rocks

Dee Estuary

Coombes & Churnet Valleys

Carngafallt

Gwenffrwd/Dinas

Cwm Clydach Nagshead Otmoor

FowlmereNorth Warren

Stour Estuary

ElmleyMarshes

Harty Marshes

Blean Woods

Cliffe Pools

Shorne Marshes

TudeleyWoods

Northward HillNor Marsh & Motney Hill

Havergate Island & Boyton Marshes

Wolves & Ramsey Woods

Farnham Heath

Fore WoodAdur Estuary

Langstone HarbourPilsey Island

Garston Wood

Lodmoor

Ham Wall

West Sedgemoor

Aylesbeare Common

HighnamWoods

Snettisham

Lakenheath FenOuse Washes

Berney Marshes & Breydon Water

Wood of Cree

Coll

Ardmore

Balranald

Loch of Strathbeg

Corrimony

Nigg and Udale Bays

HoyCottasgarth & Rendall Moss

Marwick Head

The Loons and Loch of BanksBirsay Moors Trumland

Onziebust

Troup Head

Grange Heath

Bracklesham Bay

Lewes Brooks

Broadwater Warren

South Essex Marshes

Fen Drayton Lakes

Saltholme

Wallasea Island

Newport Wetlands

Tay

Meikle Loch

Seasalter Levels

Lydden Valley

Labrador Bay

Langford Lowfields

Vallay

Great Bells Farm

Crook of Baldoon

Yell

Ramna Stacks & Gruney

Loch of Spiggie

Noup Cliffs

BrodgarCopinsay

Priest Island

Eileanan Dubha Ballinlaggan

The Reef

Oronsay

Smaull Farm

Horse Island

Aird’s Moss

Kirkconnell Merse

GeltsdaleLarne Lough Islands

Read’s Island

Tetney Marshes

Dingle Marshes

Nene Washes

Ouse Fen (Hanson-RSPB project)

Church Wood

Grassholm

Chapel Wood Greylake

WarehamMeadows

Brading Marshes

Pulborough Brooks and Amberley Wildbrooks

StoboroughHeath

Normanton Down

Barfold CopseIsley Marsh

Old Hall Marshes

The Skerries

Aghatirourke

Carlingford Lough Islands

Strangford Bay & Sandy Island

Inner ClydeFannyside

Skinflats

Inchmickery

Fidra

Edderton Sands

Fairy Glen

Eilean HoanLoch na Muilne

Colonsay

Hesketh Out Marsh

Malltraeth MarshMorfa Dinlle

Middleton Lakes

Beckingham Marshes

Sutton Fen

Winterbourne Downs

Snape

Dunnet Head

Broubster Leans

Bogside Flats

Durness

Locations of RSPB reservesFeatured reserves

1

RSPB Reserves 2012A review of our work

COMPILED BY MALCOLM AUSDEN AND JO GILBERT

ContentsOur vision 3

Introduction 5

Reserves and wildlife – a review of 2011 7Progress towards bird species targets 8Wildlife discoveries 12Land acquisition 14Condition of RSPB-managed SSSIs/ASSIs 15

Saving nature 17Re-introducing lost species to RSPB nature reserves 18Farming with nature 22Management of reedbeds for bitterns and other wildlife 24Lusty More island – restoration management for curlews in Fermanagh 28Our amazing Orkney reserves 32Meet some of our special species 36Increasing the breeding success of lowland wet grassland waders using predator exclusion fences 40Re-wetting Wolves Wood 44Managing coastal erosion – the Titchwell Coastal Change Project 46What future for our wintering geese? 50

Working in Partnership 55Reversing habitat loss at Dove Stone – from bare peat to a green recovery 56The Strathspey Wader Futurescape 60

Reserves and people – a review of 2011 65People on reserves in 2011 66Access to Nature – the South Essex People and Wildlife Programme 70Springwatch at Ynys-hir 74Nature Counts 78The economic benefits of nature reserves 82

Supporting partners around the world 87The Gola Rainforest: Sierra Leone’s first Rainforest National Park 88

Thank you to our supporters 92

2

Andy H

ay (rspb-images.co

m)

Stone-curlews continue to increase on habitat created for themat Winterbourne Downs and Minsmere.

3RSPB RESERVES 2 012

Our visionOur vision is to help achieve a wildlife-rich future

by doubling the area of land managed as RSPB nature

reserves by 2030; protecting our most special places for

birds and all wildlife; and redressing past losses through

habitat restoration and creation.

Our reserves will be wonderful places, rich in wildlife,

where everyone can enjoy, learn about and be inspired

by the wealth of nature. Working with neighbouring

landowners, we will help enhance the quality of the

surrounding countryside through our Futurescapes

programme.

Increasingly, we will focus on restoring land of low

ecological interest to that of high quality. We set

challenging targets, but more is needed given the

size of the task facing all of us.

4 RSPB RESERVES 2 012

Andy H

ay (rspb-images.co

m)

Our new nature reserve at Middleton Lakes – a place for people to connect with nature.

5I NTRODUCT ION

Over the centuries, humans have

altered our natural environment

beyond all recognition: woodlands

have been felled, heathlands

ploughed or afforested and

wetlands drained. And with these

changes, our collective memory of

what our natural environment was

like fades too. Each succeeding

generation tends to accept “their”

time as a baseline against which

further change is benchmarked.

As a conservation body, the RSPB’s

role can be captured quite simply as

trying to create a world richer in

wildlife, and wanting our children to

inherit the environment in a better state

than we found it. So we will protect the

best of our natural environment, but we

also want to restore what we have lost.

We conserve wildlife for its own sake,

and for our benefit, by providing

ecosystem services that we all

accept from the natural environment,

knowingly or not. These include clean

water, carbon storage, food, flood

defence and natural space to enjoy, to

name but a few.

During 2011, we were pleased to open

our new reserve at Middleton Lakes,

near Tamworth on the north-east edge

of the Birmingham conurbation. In this

area of wetland remodelled from old

gravel workings, we are putting

something back into an area which has

suffered huge ecological loss. Over

time, we hope that Middleton will

become a gateway site for people to

connect with nature; to enjoy, learn

and, on their return home, perhaps

commit to taking individual actions to

benefit nature.

Another site where we have been

restoring nature is at The Lodge – the

RSPB’s UK headquarters. The Lodge

protects remnant heath, once part of a

much larger sweep of heathland along

the Greensand Ridge of Bedfordshire

and Cambridgeshire. In recent years,

we have removed 44 hectares of

conifers and spread heather seed. It is

incredibly rewarding to see heather

steadily colonising the restored area.

The two sites are connected in

rather a special way. Middleton is an

important place in the ecological

history of Britain, as Middleton Hall

was home to Francis Willughby and

John Ray, who produced the first

truly scientific attempt at plant

classification. Ray’s Cambridge

Catalogue of plants, published in

1660 and researched whilst he was a

Fellow at Trinity College, describes

the botany of a now largely lost

landscape, including the Lower

Greensand ridge. He gives a vivid

insight into what we might aim for as

part of the restoration: for example,

shepherd’s cress Teesdalia

nudicaulis, found "in a sandy lay near

the windmills beyond Gamlingay

towards Sandy", is now only present

in a few small colonies. It would be

good to see its former abundance

restored. Lamb’s succory Arnoseris

minima, is now extinct and would

require reintroduction, probably to

areas of disturbed ground.

We now take the ability to identify

the plants and animals around us for

granted. But this obviously depends

on successive generations wanting

to learn how to identify plants and

animals, and having the right training

to do so.

We are clear that there are people

who wish to learn, and the creation

of identification guides, whether in

print or on-line, has done much to

support this. But the emphasis on

ecosystem processes, rather than

more traditional approaches to botany

and zoology, mean that access to

formal learning is declining. We have

been delighted to play a small role in

trying to address this skills gap

through "Nature Counts", a Heritage

Lottery Fund (HLF) supported project

under which we are supporting 12

ecologists over three years to work

with RSPB ecologists to develop their

taxonomic and identification skills,

focusing on more difficult, under-

recorded groups of species. We hope

the result will add to a new

generation of ecologists, better

equipped to help us understand and

contribute to the conservation of a

rapidly changing world, as well as

helping the RSPB to manage

reserves better in the short-term.

IntroductionSaving Nature

Martin HarperDirector of Conservation

Gwyn WilliamsHead of Reserves & Protected Areas

6

Andy H

ay (rspb-images.co

m)

RSPB nature reserves support about 7% of the UK breeding population of hen harriers.

7RSPB RESERVES 2 012

There are several strategic aims within the RSPB’s Reserves

Conservation Strategy:

• We have set ambitious targets for key bird species: to

increase the populations of 15 species and maintain

population of 11 others.

• To ensure that wildlife thrives on our reserves, we aim

to maintain rare and scarce species of plants, fungi and

animals and to enhance numbers of some of the most

threatened species.

• We will continue to create important new habitats on

existing reserves and to acquire further land where this

helps us to conserve priority species and habitats.

• For those areas of reserves designated as Sites and Areas

of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs and ASSIs) where the

RSPB is responsible for delivery of Favourable Condition,

our aim is that all are classified as in Favourable

Condition or Unfavourable-Recovering Condition.

This chapter reports on progress made towards these aims

during 2011.

Reserves and wildlifea review of 2011

8 RESERVES AND W I LDL I F E – A REV I EW OF 2 011

Andy H

ay (rspb-images.co

m)

Progress towards bird species targets

We aim to maintain the populations of

11 key bird species at or above their

2005 levels on reserves. Ambitious

targets have been set to increase

populations of a further 15 key species

breeding on our reserves by 2012

(see table, page 11).

Figures for 2011 show mixed

progress, with populations of a

range of species declining on RSPB

nature reserves in 2011, probably for

a variety of reasons. Four species

are making good progress towards

achieving their ambitious increase

targets, and eleven species are

expected to maintain their existing

numbers on reserves. Seven

species appear unlikely to achieve

their existing targets on reserves,

with an additional two species

likely to fail to colonise, or

re-colonise, RSPB reserves. The

remaining two priority species are

not monitored regularly on RSPB

nature reserves.

Numbers of black grouse have almost doubled on RSPB nature reserves since 2005.

Species making good progresstowards achieving their 2012“increase” targetsFour species are currently on track to

achieve their 2012 increase targets:

bittern, black grouse, crane, and

stone-curlew.

Numbers of booming bitterns on

reserves continued to increase, with

our strategy of creating reedbed for

bitterns and other species away from

vulnerable coastal areas continuing to

pay off. The increase was particularly

pleasing, especially given the severity

of the previous winter. At Ham Wall

(see page 26), there were 10 booming

bitterns and seven nests (eight

boomers and eight nests in 2010).

At Lakenheath Fen, there were seven

boomers and seven or eight nests

(six boomers and five nests in 2010).

Black grouse also increased, despite

the winter conditions. At Geltsdale,

there were 45 lekking males. This

compares with 38 in 2010, and 18 in

2009. Numbers of lekking male black

grouse also increased from 10 to 19

at Lake Vyrnwy.

Cranes nested successfully at

Lakenheath Fen for the third year

running. There were two pairs and

these fledged one young. A pair of

cranes bred for the second year

running at the Nene Washes, and

again fledged one young. Of the 21

cranes released into the Somerset

Levels in 2011, 18 survived their first

winter. A further 17 have been

released in 2011, and these two age

groups are interacting well together.

Numbers of breeding stone-curlews

continued to increase at

Winterbourne Downs, and on the

acid grassland created at Minsmere.

There were 13 pairs of stone-

curlews breeding at these two sites

in 2011, compared with just two

pairs in 2005.

9RESERVES AND W I LDL I F E – A REV I EW OF 2 011

Species making good progresstowards achieving their 2012“maintain” targetsEleven priority species are expected

to achieve their 2012 Reserves

Conservation Strategy “maintain”

targets: Slavonian grebe, common

scoter, hen harrier, spotted crake,

corncrake, black-tailed godwit

(limosa race), whimbrel, woodlark,

chough and, on lowland wet

grassland, redshank and lapwing.

Some of these remain on track

overall, despite recent declines.

Slavonian grebes are maintaining

their numbers on the RSPB reserve

at Loch Ruthven, but have declined

on the rest of the loch. Numbers of

Slavonian grebes increased on the

loch as a whole in 2011. Slavonian

grebes had a good breeding season

at Loch Ruthven in 2011, raising 11

young on the whole loch. This bodes

well for 2012.

Numbers of lapwings, redshanks

and snipe breeding on our lowland

wet grassland reserves declined for

a second year running. Some of

these declines were probably at

least in part due to the dry weather

conditions in spring, and might also

be the result of a second hard

winter reducing overwinter survival.

Numbers of breeding black-tailed

godwits remained fairly stable at the

Nene Washes RSPB Reserve (43 in

2011, compared to 44 in 2010).

Efforts to maintain wet grassland-

breeding waders in the countryside

outside nature reserves, through our

Futurescapes programme, are

described on pages 60-63. These

contrast with the more extreme

interventions that are now having to

be used to maintain isolated core

breeding populations of lapwings in

areas where their numbers have

collapsed in the surrounding

countryside (pages 40-43).

Numbers of spotted crakes were

particularly low in 2011, but numbers

arriving in the UK are known to often

fluctuate greatly from year to year.

Total numbers of choughs breeding

on RSPB reserves have only

declined slightly since 2005, but

have shown a large decline at The

Oa, from seven pairs in 2006 to just

two in 2011 (but with another two

pairs nesting just off the reserve).

A key problem for these choughs is

low first year survival. A project is

underway to look at foraging and

food preferences during the post-

fledging period.

Mark H

amblin (rsp

b-images.co

m)

Common scoters breeding on RSPB reserves have remained fairly

stable since 2005.

10 RESERVES AND W I LDL I F E – A REV I EW OF 2 011

Ben Hall (rsp

b-images.co

m)

Dartford warblers declined on some RSPB nature

reserves in 2011, almost certainly due to the hard winter.

Species making unsatisfactoryprogress towards achievingtheir 2012 “maintain” targetsSeven species are currently not on

track to achieve their 2012 “maintain”

targets: snipe (on lowland wet

grassland), red-necked phalarope,

capercaillie, little tern, nightjar,

Dartford warbler and golden oriole.

An additional two species, cirl

bunting and black-necked grebe,

have failed to achieve our target of,

respectively, colonising and re-

colonising RSPB nature reserves

(although single pairs of black-necked

grebes have bred for single years at

three sites during the five years).

Numbers of male red-necked

phalaropes on the RSPB’s managed

mires on Fetlar remained the same

as in 2010 (eight males). This follows

two years of increases following the

clearance of existing pools, and

creation of new pools in these mires,

prior to the 2009 breeding season.

Numbers of returning males to the

UK are thought to be determined to a

large extent by off-site factors related

to conditions at sea in their (as yet

unknown) wintering grounds. Despite

this, we still need to maintain good

habitat conditions for them on our

nature reserves, so that returning

birds can breed successfully.

There were 40 lekking male

capercaillie at Abernethy, up from 31

last year. This increase follows good

productivity in 2010, when 23 chicks

were recorded from 25 hens.

Productivity was lower in 2011 (12

chicks recorded from 34 hens).

Little terns declined slightly on

RSPB nature reserves in 2011, and

productivity was generally low at their

main RSPB sites. This low productivity

was due principally to predation and/or

storms washing out nests. The long-

term prospects for little terns in the UK

appear poor, unless improvements to

their breeding sites can be made on a

large scale. This species has suffered a

long-term decline in Britain, explained

by low breeding productivity. Pressure

on breeding little terns is likely to

increase further, as a result of sea-level

rise, and possibly increases in

recreational use of coastal areas.

Numbers of Dartford warblers breeding

on RSPB reserves declined sharply in

2011, due to reductions in numbers at

Arne (from 52 pairs in 2010, to 17 pairs

in 2011) and Aylesbeare Common (from

13 pairs in 2010 to three pairs in 2011),

both no doubt caused by the prolonged

cold period during the previous winter.

Numbers of Dartford warblers remained

fairly stable at other RSPB sites.

The decline in numbers and likely

imminent extinction of breeding golden

orioles in the UK (Lakenheath Fen has

probably been their only regular

breeding site in the UK), mirrors their

decline on the near-Continent. There is

nothing to suggest that it is due to

changes in the extent or quality of

breeding habitat in the UK.

11RESERVES AND W I LDL I F E – A REV I EW OF 2 011

Steve K

nell (rsp

b-images.co

m)

Species 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012target

Slavonian grebe 2 2 3 4 4 2 3 2

Black-necked grebe 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 5

Bittern (booming males) 18 19 20 26 29 34 37 34

Common scoter 11 14 10 10 12 11 11 11

Hen harrier (nests)* 53 - - 43 56 47 48 59

Black grouse (lekking males) 104 151 189 174 141 169 195 170

Capercaillie (lekking males) 48 39 47 41 32 31 40 60

Spotted crake (calling males) 10 13 14 12 12 10 5 10

Corncrake (calling males) 242 266 294 240 289 246 245 330

Crane 0 0 1-2 2 2 3 3 3

Stone-curlew 7 7 6 10 12 17** 20** 20

Lapwing (on lowland wet grassland) 1,311 1,366 1,392 1,458 1,500 1,402 1,249 1,650

Snipe (drumming males on lowland wet grassland) 542 579 495 565 568 507 357 700

Black-tailed godwit race limosa 46 50 43 43 43 45 44 46

Whimbrel 10 - >8 8 - 8 - 10

Redshank (on lowland wet grassland) 1,070 1,128 1,180 1,196 1,192 1,178 1,057 1,300

Red-necked phalarope (males) 18 12 8 6 11 13 11 18

Little tern 191 127 137 113 122 122 106 191

Nightjar*** 71 75 68 65 59 63 60 71

Woodlark*** 38 51 53 50 50 33 33 38

Dartford warbler*** 139 108 c 125 c 147 c 85 100 59 165

Crested tit c 200 - - - - - - c 200

Golden oriole 2 2 3 2 2 0-1 0 4

Chough 31 34 37 34 33 32 29 40

Scottish crossbill (individuals) - - - 23 - - - -

Cirl bunting 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

Note: Figures are pairs except where stated otherwise. * The original target has been revised because of changes in recording area at one of their key sites, Forsinard Flows.** Includes two females, which both laid in the same nest, and which we have counted as separate “pairs”.*** The original target has been revised because one of the sites at which they breed, Avon Heath, is no longer an RSPB reserve, and because of changesin recording at North Warren.

Populations of priority bird species on RSPB reserves present in 2005In some cases the population on the entire RSPB reserve network is higher than this, because birds on land acquired

since 2005 have not been included in this table.

Slavonian grebes enjoyed a good breeding season at Loch Ruthven in 2011,

but their status as a breeding species in the UK remains precarious.

12 RESERVES AND W I LDL I F E – A REV I EW OF 2 011

Wildlife discoveriesIn 2011, RSPB ecologists discovered

a population of the beetle Omophron

limbatum in a new area of East

Anglia. This is one of the rare beetles

found at the margins of pools at

Dungeness. For many years Rye

Harbour and Dungeness were long

thought to be the only British

localities for this species, but several

new sites were found in Breckland in

Norfolk and Suffolk in the first few

years of the 2000s. It seems that

Omophron limbatum has colonised

Britain at least twice, because the

beetles in East Anglia are darker and

more extensively marked than those

in Kent and Sussex. The beetles at

the new site match those from

Breckland, so they are likely to have

come from the same source.

One of the RSPB's Nature Counts

trainees (see page 78) made a very

unexpected discovery at South Stack

Cliffs. The beetle, Calosoma inquisitor,

known as the caterpillar-hunter, is

associated with ancient woodlands.

It is a scarce and spectacular beetle,

but it has been lost from a number

of its former sites. Colin Lucas found

one walking across the maritime

heathland at South Stack, several

kilometres from the nearest sizeable

wood. Calosoma inquisitor does not

seem to have been recorded from

Anglesey before; the nearest

locations in the provisional atlas of

ground beetles are on the Welsh

mainland. So if this was a wanderer

it was very lost indeed, but there is

the exciting possibility that there is

a resident population of Calosoma

inquisitor on Holy Island in a

heathland habitat. We shall look for

it again in 2012.

The trainees in Scotland, Clare

Rickerby and Ndurie Abah, found

a new colony of Orthotrichum

obtusifolium at Insh Marshes. This

rare moss is found on tree trunks

in eastern Scotland. It was lost from

England more than a hundred years

ago, but it has recently been found

in a few places in East Anglia, so it

might be recolonising.

Genetic analysis of tooth fungi from

Abernethy has confirmed two new

species for Britain. In 2010,

mycologists Martyn Ainsworth and

Alan Lucas collected some

specimens with the help of former

Discovery of a new site for the beetle Omophron limbatum

was one of the highlights of 2011.

Mark G

urney

13RESERVES AND W I LDL I F E – A REV I EW OF 2 011

One of the mystery tooth

fungi at Abernethy has

been identified as

Hydnellum cumulatum,

a new species for Britain.

Mark G

urney

site manager Stewart Taylor, who has

mapped the distribution of tooth

fungi at the reserve every autumn for

the last five years (see RSPB

Reserves 2009). The results of their

analysis of these confusing fungi

show that Hydnellum cumulatum and

Hydnellum gracilipes grow in several

places at Abernethy and in nearby

pinewoods. Several other collections

from Abernethy are still being

analysed, and they appear to include

some undescribed species, so there

should be more new records to

report in future.

In 2011 the BTO staff and the RSPB

staff challenged each other to find as

many species as possible on their

headquarters nature reserves. Here

at The Lodge we found and identified

2,025 species, of which more than a

third had not been recorded before.

Several species were added to the

county list, and among the additions

to the reserve list were 45 rare or

scarce species, including a new moth,

the square-spotted clay; a distinctive

dead-wood beetle Tomoxia

bucephala; and Theridion pinastri, a

handsome spider associated with

heaths and open woods.

Five-spot ladybird Coccinella

quinquepunctata is known from a

number of places in the Spey Valley.

Steve Wilkinson, a long-term volunteer

at Insh Marshes, set out to try to find

it on the reserve in April 2011. His

search was successful, and he added

this unusual ladybird, which lives

among river shingle, to the reserve

list. Also new to Insh Marshes, and to

Scotland, was the conformist, a

spring-flying moth found by Matthew

Deans and Paul Bryant. This extremely

rare species used to be resident in

South Wales, but it has recently been

recorded only as a vagrant in Britain.

Matthew and Paul also found Kentish

glory, Rannoch sprawler and sword-

grass on the reserve.

More than 15,200 native species have

now been found on RSPB reserves;

just under one third (32%) of all UK

land and freshwater wildlife. We look

after many threatened species, from

sand-dwelling beetles on the sea

shore to rare sedges on the top of

Cairn Gorm. You can help us by telling

reserve staff if you find anything

unusual when you visit our reserves.

14 RESERVES AND W I LDL I F E – A REV I EW OF 2 011

Land acquisitionDuring 2010/11, the Society acquired

8,446 hectares to add to its land

holding. This area comprised four new

nature reserves totalling 6,658 ha

(78.8% of the total) and the extension

of 13 reserves (21.2% of the total).

On 1 April 2011, the RSPB managed

141,833 ha at 211 reserves, of which

57% is owned, with the remainder

leased or under management

agreement. The new reserves were:

� Great Bells Farm, Isle of Sheppey,

Kent (lowland wet grassland

restoration in partnership with the

Environment Agency)

� Dove Stone, Greater Manchester

(upland heath in partnership with

United Utilities – see pages 56–59)

� Eastern Moors, Derbyshire (upland

heath and woodland in partnership

with the National Trust and Peak

District National Park)

� The Crannach, Deeside (upland

heath and Caledonian pinewood)

At Ouse Fen, Cambridgeshire, the

first transfer of land from Hanson to

the RSPB occurred and significant

extensions were added to Wallasea

Island, Essex; Dearne Valley, South

Yorkshire; Saltholme, Cleveland, and

at Forsinard Flows, Highland.

Our supportersIn 2010/11, we received £1,234,300 in

grants for land acquisition. A number

of these were from private donations,

particularly at Forsinard Flows,

Highlands, and Wallasea Island, Essex.

We are grateful to all our supporters –

a comprehensive list and

acknowledgement is published in the

RSPB 2010–11 Annual Review.

Ben Hall (rsp

b-images.co

m)

Our new nature reserve at Dove Stone in Greater Manchester,

managed in partnership with United Utilities.

15RESERVES AND W I LDL I F E – A REV I EW OF 2 011

Condition of RSPB-managed SSSIs and ASSIs

Almost three-quarters of the land

managed by the RSPB is designated

as SSSI/ASSI (Site/Area of Special

Scientific Interest), reflecting the high

value of the RSPB’s reserve network.

In England, 93.4% of the area of

SSSIs managed by the RSPB is in

Favourable Condition or Unfavourable-

Recovering Condition. Remedies have

been agreed with Natural England for

99.996% of the area of SSSI land

which is in Unfavourable Condition,

and for which the RSPB is

responsible for its management.

Chris G

omersall (rsp

b-images.co

m)

RSPB nature reserves support approximately 700,000 wintering and passage waders

and wildfowl, including large numbers of knots and dunlins.

We do not have recent data on the

condition of RSPB-managed SSSIs in

Scotland. As of April 2010 (for which

the most recent data are available), of

802 features assessed, 660 (82.3%)

were assessed as being in Favourable

or Unfavourable-Recovering Condition.

The 142 features assessed as being

in Unfavourable-Declining or

Unfavourable-No-Change include a

large number not in RSPB

management control. This reflects, in

particular, the large number of

breeding seabird SSSI and SPA

features on the RSPB’s reserve

holdings in Scotland, as well as a

more widespread attribution of

Unfavourable Condition of bird

features to influences with no

“on-site” remedy. Taking this into

account, 95% of the features for

which there are considered to be on-

site remedies are now in Favourable

Condition.

Information on the condition of

RSPB-managed units in Wales and

Northern Ireland is not available

from the statutory conservation

organisations.

16

Roseate tern

by Chris G

omersall an

d heath

fritillary by Jackie C

ooper (b

oth rsp

b-images.co

m). G

round beetle b

y Roy Anderso

n. Fen

orchid, an

t-lion and fungus by M

ark Gurney.

Just a few of the many fabulous species for which RSPB

nature reserves support a large proportion of their UK

population. Clockwise from top left: roseate tern, heath

fritillary, the ground beetle Badister meridionalis, fen orchid,

ant-lion, and the fungus Stereopsis vitellina.

17RSPB RESERVES 2 012

Saving natureAn amazing variety of birds, plants, animals and fungi depend on

RSPB nature reserves for their survival, particularly species with

small UK populations that have specialised requirements. Over the

last half century, RSPB reserves have played an important part in

preventing the extinction of several UK breeding birds, such as

marsh harriers and Dartford warblers, and have greatly aided the

recovery of others, such as bitterns, avocets and corncrakes.

Increasingly, we are managing habitats for other wildlife and are

focusing attention on rare and threatened species with important

populations on our reserves, and those threatened through loss of

habitat elsewhere.

18

Ellen

Rotheray

The RSPB’s role in reintroduction projects for birds is

widely recognised, but fewer people are aware of our

work translocating other animals and plants to our

reserves. As translocation of species has become more

widely regarded as a valuable tool for conservation, so

the number of translocation projects on RSPB nature

reserves has increased.

JANE SEARS, BIODIVERSITY PROJECTS OFFICER

Reintroducing lost species to RSPB nature reserves

The pine hoverfly is arguably

the most endangered hoverfly

in the UK.

19SAV ING NATURE

As long ago as the early 1980s,

natterjack toads were translocated to

The Lodge and Minsmere nature

reserves, and in the 1990s we

helped establish a silver-studded blue

colony at Aldingham Walks in Suffolk.

Now we are helping to secure the

future for some of the UK’s most

threatened species. By providing

continuity of suitable habitat

conditions, our reserves can help

maintain and enhance existing

populations of vulnerable species

that are confined to very few sites,

or help restore populations of

species that have gone extinct

in the UK.

We consider that reintroduction

should be used judiciously and

should never be a substitute for

conserving species through habitat

conservation at their existing sites,

or encouraging natural colonisation

of suitable alternative sites.

We recognise the opportunity that

habitat creation schemes provide to

restore species to their former

ranges, or to provide alternative sites

when their existing habitat is

threatened through changes, such as

sea level rise. All of our projects are

carried out in partnership with other

organisations, and proposals are

assessed against IUCN guidance.

The following three cases illustrate

our approach to wildlife translocation

projects.

Pine hoverfly – an unwillingcolonistThe pine hoverfly Blera fallax is

arguably the most endangered

hoverfly in the UK, having been

confined to just two Scottish native

pinewoods in Strathspey since the

1990s. It was previously known from

eight sites including the RSPB’s

Abernethy reserve, where it was last

recorded in 1982. The species is

saproxylic or “rot-loving”, requiring

wet decay in holes naturally found in

dead and decaying trees, or within

the stumps of trees cut for forestry.

It is thought to have declined due to

changes in forestry practices, and a

lack of over-mature, senescent or

dead trees in Scottish native

pinewoods.

Since 1999, the RSPB has been

working with Scottish Natural

Heritage (SNH) and the Malloch

Society to increase populations at the

two known sites, and to provide

suitable habitat at neighbouring sites,

including Abernethy, hoping that the

hoverfly would expand its range

naturally through dispersion. Having

studied the hoverfly’s ecological

requirements, we found that by

cutting slots in cut stumps and filling

them with wood chips, we could

increase the amount of breeding

habitat available (see photograph).

Although the population at one of the

sites increased, after five years none

of the neighbouring sites had been

colonised, so reintroduction was

considered necessary.

In 2007, the pine hoverfly was

included in SNH’s Species Action

Framework (SAF) with a target to

“achieve an increase in range to five

sites by 2012”. Captive breeding of a

saproxylic hoverfly had not been

attempted before, so a technique

was developed by Ellie Rotheray, a

PhD student at Stirling University.

Reintroductions to historic sites

commenced in 2009, with the first

Ellen

Rotheray

of three years of releases at

Rothiemurchus Estate, and then in

2010 and 2011 to the RSPB’s

Abernethy reserve. Each year at

Abernethy, through our “deadwood

creation programme”, a few plantation

pines will be felled and stumps cut to

provide continuity of habitat for the

hoverfly, and to benefit other species

too. After three years of releases,

larvae will be monitored annually in

the hope that a self-sustaining

population of the pine hoverfly will

become established.

Slots are cut into pine stumps to

provide extra breeding habitat for

pine hoverflies.

I. MacG

owan

The female pine

hoverfly has a

lighter tail than

the red-tailed male

(shown opposite).

20 SAV ING NATURE

emergency measures were called for,

so a programme of reintroductions

commenced, supported by Natural

England’s Species Recovery

Programme. Since then, populations

have been established at four sites

within the species’ historic range in

southern England, and there are

Rowan Edwards

Field cricket – new homes onrecreated heathlandIn the early 1990s the endangered

field cricket, Gryllus campestris, a

flightless “true cricket”, numbered

fewer than 100 individuals in the UK,

all present at one site in West Sussex.

With very limited dispersal powers,

ongoing reintroductions to several

others to increase connectivity

between the sites.

We are contributing to this programme

through heathland recreation work at

two of our reserves; Pulborough

Brooks in Sussex and Farnham Heath

in Surrey. By removing trees from the

former heathland, we are restoring the

type of conditions the field cricket

requires for burrowing and foraging:

warm, tussocky grasslands with light

soil and up to 50% bare ground. Field

cricket nymphs were released in 2010

and 2011, and adult calling males were

heard at both sites during 2011. Further

releases will be made to suitable

habitat in adjacent areas to extend the

occupied range at each site, and the

habitat will be managed to retain the

early successional conditions.

Jane Sears (R

SPB)

Male field crickets call from their “sun-beds” of warm bare ground.

Once released,the field cricketsquickly digburrows.

21SAV ING NATURE

Short-haired bumblebee –benefiting other declining beesRestoring species that have gone

extinct in a country is never easy,

especially when the life-cycle of the

source population is six months out of

sync with the season where it is being

re-introduced, and on the other side of

the world! That was the challenge

facing us when we joined with Natural

England, Bumblebee Conservation

Trust and Hymettus in an ambitious

programme to restore a native

population of the short-haired

bumblebee Bombus subterraneus to

the UK. Once widespread across the

south of England, occurring as far

north as Humberside, the short-haired

bumblebee suffered a major decline

from the 1960s onwards and was

declared extinct in the UK in 2000. Its

decline was almost certainly the result

of the loss of the species-rich

grassland on which it depends. It was

last recorded near the RSPB’s

Dungeness reserve in 1988, but a

population of UK origin survives in

New Zealand, where it was introduced

in 1895 to pollinate red clover.

The project has assisted in the

creation and restoration of more than

550 ha of flower-rich habitat within the

Dungeness and Romney Marsh area.

This includes 4 ha of arable reversion

on the RSPB’s Dungeness reserve,

which has benefited other declining

bumblebee species, such as the shrill

carder bee Bombus sylvarum and the

large garden bumblebee Bombus

ruderatus, recorded there for the first

time in 2010. Two attempts to captive

breed the bee in New Zealand were

unsuccessful, and a genetic study

suggested high levels of inbreeding.

The decision was therefore made to

source the bees from Sweden, rather

Nikki G

ammans

than attempt to return bees of UK

origin. Subject to satisfactory disease

screening, we anticipate the first

release of queen bees at the RSPB’s

Dungeness reserve in spring 2012.

In future, we anticipate an increasing

need for translocations as populations

become more threatened and

fragmented, and vulnerable to the

impacts of climate change. We need

to learn from past and current

experience, and develop the expertise

to ensure the greatest chances of

their success.

Nikki G

ammans

A farm day event to learn about bumblebees.

Short-haired bees are to return to the UK after an

absence of nearly 25 years.

If asked, most people will say that the RSPB’s

involvement in farming is confined to advising

farmers and landowners on the management of their

land for birds and other wildlife, or carrying out bird

surveys on their land. This is far from the truth,

however – yes, the advisory function is a big part of

our work, but the Society is also very much involved

with farming by letting land to farmers, and farming

on its own account alongside, and with, nature.

IAN BAKER, HEAD OF LAND AGENCY

Farming with nature

Many of our reserves, as here at West Sedgemoor, provide grazing for local farmers’ livestock.

Malco

lm Ausden

22

23SAV ING NATURE

The RSPB manages more than

140,000 ha of land for nature

conservation, a significant proportion

of which depends on agricultural

management, particularly grazing by

sheep and cattle. We carry out farming

at a large scale, working within the

boundaries of the EU Single Farm

Payment and agri-environment

schemes. Our farmed estate is varied,

and we take on different roles to suit

local circumstances.

We carry out in-hand farming,

involving managing our own livestock,

at a number of reserves where it

makes sense both economically

and ecologically. Practical farming

experience is therefore important

as it helps inform our approach

through agricultural policy to matters

such as Common Agricultural Policy

(CAP) reform.

We also let out large areas of land to

local graziers. Sometimes a

shepherding service is provided either

by skilled RSPB staff or local farmers.

This is the most cost-efficient way of

managing vegetation on reserves, and

avoids the Society investing in

livestock at a high capital cost.

To help tailor the sometimes unusual

demands of nature conservation with

commercial farming, the RSPB has

developed incentivised tenancies.

These offer a rebate from the agreed

rent upon delivery of features

beneficial for nature conservation.

These features can be a specified

grass height, or the application of

farmyard manure.

In 2011, there were 350 farmers with

640 agreements with the Society,

farming more than 23,000 ha on our

nature reserves across the UK.

Agreements vary from terms of one

grazing season to five year tenancies,

and are drawn up according to the

circumstances and needs of the

reserve. In all cases, we try to ensure

the farmer and the RSPB benefit from

the EU Single Farm Payment and

agri-environment schemes. Indeed

agri-environment grant is essential

to help support the costs of

management, especially in keeping

Natura 2000 sites in favourable

condition. This also requires the RSPB

to meet the rigorous requirements

of cross compliance (meeting certain

statutory and management

conditions) across all its reserves in

order to receive that money. Sites

and livestock are regularly inspected

by government agencies to ensure

these standards are met.

Latterly, the RSPB has become more

involved in the management of large

scale farming operations, for example

at Lake Vyrnwy for the last 15 years,

but more recently at Dove Stone, on

the moors in north west Derbyshire,

and at Haweswater, in the Lake

District. These schemes are managed

in conjunction with public utility

companies who have a legal

requirement to meet EU targets on

water quality at the lowest cost

commercially. The work at Dove Stone

is described on page 56.

Farming and Natura 2000 sites

In places, our farming activities

take place within, and are

essential to the management of

“Natura 2000” sites – Special

Protection Areas and Special

Areas of Conservation which are

the most important sites in

Europe for wildlife.

Within these areas, management

practices are required to maintain

(or where necessary to restore)

the value of the habitats that they

protect. The protection afforded to

these special places does not

prevent their ongoing agricultural

use. But it does ensure that these

special places are managed with

wildlife in mind, and provides a

focus for both partnerships and

funding to deliver innovative

agricultural management.

RSPB also carries out

large-scale, in-house

farming operations, such

as here at Loch Gruinart.

Andy H

ay (rspb-images.co

m)

Management of reedbeds for bitternsand other wildlife

A view across the reedbed at Ham Wall towards Glastonbury Tor.

Although well known for their bird life, reedbeds also

support a wide variety of invertebrates, including rare and

specialised species dependent on reed. They also provide

important refuges for water voles from mink predation.

The RSPB is working closely with others to develop and

promote reedbed management for all of its special

wildlife interest.

MATT SELF, RESERVES ECOLOGIST; STEVE HUGHES, SITE MANAGER, HAM WALL;

JANE SEARS, BIODIVERSITY PROJECTS OFFICER

David

Kjaer (rsp

b-images.co

m)

24

25SAV ING NATURE

Reedbed is a rare habitat with only

an estimated 6,600 ha in the UK.

Since the RSPB leased its first

reedbed at Minsmere in 1947, we

have majored on restoring and

re-creating reedbeds and now

manage approximately 1,600 ha of

the habitat.

Much of the reedbed creation and

management has been led by the

requirements of bitterns. Despite

targeted management work through

the 1990s, bittern numbers declined

to a low of only 11 boomers at just

seven sites in 1997. This led to a

re-energised campaign of reedbed

restoration and re-creation with other

organisations and agencies, helped

by EC LIFE-Nature and informed by

detailed research work on the

behaviour and requirements of

bitterns. The results have been

favourable with an impressive

increase in bittern numbers.

Numbers of booming bitternsin 2011

The graph shows the increase in

numbers of booming bitterns since

the start of reedbed creation, at Ham

Wall in 1994, and at Lakenheath Fen

in 1996. These, and other reedbeds,

have been created to compensate for

the loss of coastal freshwater

reedbeds due to rising sea levels. Of

the 12 RSPB sites with bittern nests

in 2011, five (with 12 nests) are at risk

of imminent coastal flooding. Inland

reedbeds, such as at Ham Wall and

Lakenheath Fen, will become

increasingly important.

There were 10 booming

bitterns at Ham Wall in

2011, just one fewer than

the total number of

booming bitterns in the

whole of the UK in 1997.

Richard

Revels (rsp

b-images.co

m)

2

4

6

8

10

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Year

Nu

mb

er o

f b

oo

mer

s

Ham Wall

Lakenheath Fen

0

26 SAV ING NATURE

Creation and management ofreedbed at Ham WallOne of the key sites for bitterns is

Ham Wall. This was created from

former peat extraction areas in the

Somerset Levels, starting in 1994,

and is one of the best examples of

how a degraded industrial site can be

turned into good wildlife habitat. In

18 years, the site has expanded to

230 ha, of which at least 153 ha is a

diverse mix of reed, mixed swamp

and inundation communities, pools

and ditches.

Ham Wall was acquired in phases, as

peat extraction was completed in

each block of around 20 ha. The mix

of vertical banks and deep pools was

re-worked with diggers to create a

network of channels, open water

bodies and reed blocks. With deep

voids and relatively little material to

rework, most areas have more open

water and more deeply-flooded reed

than in a typical reedbed. This has

proved to be ideal fish habitat, and

the very wet reedbeds have turned

out to be very resistant to the

accumulation of litter and debris, and

the succession process. Rudd were

introduced to the site to increase

food availability, and they have

thrived. More recently, an eel pass

(provided by the Environment

Agency) has been installed to allow

access to the reedbeds from the

separate main drain nearby.

It is often difficult to keep up with the

scale of reed management at large

reedbed sites, and with the disposal

of arisings from reed cutting. Ham

Wall has managed particularly large

areas of reed, typically over 5 ha per

year, and has developed innovative

approaches to these problems. Much

of this has been tackled with a

specialised low ground pressure flail

harvester (based on a “Softrak”

platform), supplying “pods” which

turn cut reed into garden compost.

An alternative to this traditional cut-

and-remove process is also being

trialled at Ham Wall, aiming to

“rejuvenate” a block of reed by

lowering water levels, undertaking

an initial cut, then introducing hardy

cattle (Highlands) to the developing

grass sward. The first rejuvenated

block is due to be re-flooded in 2012.

Work at Ham Wall started in 1994,

but it took until 2003 for the first

booming bittern to be heard. No

nesting attempts took place until

2008, when there were two boomers

and two nests. Since then numbers

have increased greatly, to 10

boomers and seven nests in 2011.

Bringing Reedbeds to LifeAn understanding of reedbed design

and management for birds has been

developed over many years, but there

is less information on the

requirements of other wildlife.

Within the RSPB and Natural England

Steve H

ughes

The Softrak cutter in action, cutting and removing reed.

27S AV I N G N AT U R E

Matt S

elf

Reed re-growing in the rejuvenation areas following lowering of water levels and cutting.

The vigour of the re-growth is further reduced by grazing.

(NE) Bringing Reedbeds to Life

project, a range of taxa and their

microhabitats were surveyed in detail

at Norfolk Wildlife Trust’s Hickling

Broad, NE’s Stodmarsh National

Nature Reserve (NNR) and the

RSPB’s Ham Wall reserve, to

improve our understanding of the

value of reedbeds and develop

suitable management

recommendations. The importance

of dry areas within reedbeds for

invertebrate diversity was

re-confirmed, but the value of wet,

early successional reedbed for

specialist invertebrates was also

demonstrated. Seasonally flooded

pools were important for common

frogs, and well vegetated ditches

were important for smooth newts.

Water voles and mink were found to

be co-existing at all the sites,

reinforcing the belief that reedbeds

provide refuges for water voles

from mink predation.

As a relatively new restoration site

on degraded peat excavations, it was

expected that Ham Wall would have a

poorer fauna than the mature and

long-established reedbeds at Hickling

Broad and Stodmarsh. However, a

respectable 552 species of

invertebrate were identified at Ham

Wall. This was similar to the numbers

recorded at the other sites. Numbers

of wetland specialists and reedbed

specialists (those dependent on reed,

reared from reed or only found in

reedbed habitats) were also similar at

the three sites. Seventeen Nationally

Rare or Nationally Scarce flies were

recorded at Ham Wall. Two are

classed as Vulnerable (the ornate

brigadier soldierfly Odontomyia ornata

and the hoverfly Sphaerophoria loewi)

and one Near-Threatened (the

dancefly Poecilobothrus ducalis),

together with eight UK BAP species

of moths. Ham Wall also supported

good numbers of common and marsh

frogs and smooth newts were

recorded even within pure reed.

All parts of the hydrological gradient

within reedbeds have biodiversity

and conservation value, and dynamic

management that maintains a range

of successional stages is key to

maintaining a high diversity of

wetland species. We have also

demonstrated the value of re-created

reedbeds for a range of species in

addition to bitterns. Combined with

an extensive programme of reedbed

auditing and the provision of advice,

it is hoped this work will result in

a coherent strategy for reedbed

conservation for the next decade.

Thanks to:

EC LIFE-Nature for funding reedbed

creation work, and to NE for

supporting the Bringing Reedbeds to

Life project, via the Countdown 2010

Biodiversity Action Fund.

28 RSPB RESERVES 2 01128

The Lower Lough Erne Islands Reserve in County Fermanagh

is the RSPB’s most westerly reserve and comprises 39 islands

in the UK’s third largest freshwater lake. It is home to an

important population of breeding waders, and targeted

management over the past 11 years has reversed declines in

breeding lapwings and redshanks. Work is currently

underway on the largest of the islands to benefit the

curlew, a species in rapid decline as a breeding bird

across the whole of Ireland.

BRAD ROBSON, FERMANAGH AREA MANAGER

Lusty More Island – restoration managementfor curlews in Fermanagh

The once widespread curlew is now confined to a smallnumber of islands and wetland sites in Fermanagh.

Steve R

ound (rsp

b-images.co

m)

29SAV ING NATURE

The curlew is familiar to many people,

having been a widespread breeding

species in both meadows and bogs.

However, this distinctive wader is in

serious trouble on its Irish breeding

grounds, both in the north and south.

In 2011, BirdWatch Ireland, the BirdLife

partner in the Republic of Ireland (ROI),

estimated the breeding population of

curlews in ROI to be fewer than 200

pairs. In Northern Ireland, the breeding

population was estimated at 5–6,000

pairs in 1986–87 (Partridge 1988). By

2000, this population had decreased

by 60% across both key breeding

wader sites and the countryside

outside these areas (Stanbury et al.

2000). Although there is not a more

recent estimate, evidence suggests

that the population is now at a critically

low level. The breeding population on

the reserve has declined from 57 pairs

in 1994 but has remained stable at

34–35 pairs since 2007.

Lusty More Island is, at 38 ha, the

largest island on the reserve, and the

most varied. More than 230 species

of vascular plant have been recorded

including cowbane and purging

buckthorn. The woodland is home to

several species of fungi found

nowhere else in Ireland; marsh

fritillary has been recorded and otters

are regularly seen along the shore. It

is owned by Fermanagh District

Council and the RSPB manages it in

partnership with a local farmer. It is a

wonderful example of a low input

grazing system benefiting a wide

variety of wildlife.

The open grassland of the interior is

hidden from the lough by an

encircling belt of oak and ash

woodland, making the meadows

unattractive to breeding lapwings and

redshanks. However, up to three

pairs of curlews and five pairs of

snipe have bred on the island for

many years. Curlew productivity has

been poor, with young only fledging

in two of the past 14 years of

monitoring. The dense woodland and

close proximity to a neighbouring

island, where foxes regularly take

© Crown Copyrig

ht, Lan

d and Pro

perty S

ervices,Licen

ce number 1548, M

ay 2012

The removal of field boundary trees and encroaching scrub will createa large open centre to the island suitable for breeding curlews and freefrom disturbance.

Ray K

ennedy (rsp

b-images.co

m)

Redshanks do not breed on Lusty More although targeted management onother reserve islands has increased the population from 23 to 52 pairs.

30 SAV ING NATURE

food handed out from a restaurant,

have hampered efforts at control.

An aerial photograph from 1969

shows the island at a time when the

then owner had cleared trees after

many years of abandonment, in an

attempt to revive the working farm.

However, this project ran into

difficulties and after the initial work it

was abandoned to a low level of

cattle grazing and consequently

scrub re-invaded the edges of the

meadows. In 2011, funds were

secured from SWARD through the

NI Rural Development Programme

2010 and, where appropriate, stumps

have been painted with glyphosate

immediately after felling to minimise

re-growth. All felling has been done

using chainsaws, with cut materials

stacked close to existing woodland,

removed or burnt where appropriate.

A 20-minute boat journey from the

mainland has added to the logistical

complexity of the operation; the

RSPB cot, usually used to transport

livestock, has been used to transport

machinery and materials.

With habitat restoration nearing

completion, the second phase of the

project will begin in August 2012. A

2 km solar-powered electric predator-

proof fence will be erected around

the meadows to exclude foxes. On

the reserve’s Rabbit Island, curlews

breed at a density of 1.2 pairs per

hectare. Lusty More is quite different

from that site but it is hoped that

following restoration, and in the

absence of fox predation, it could

support 10 pairs of breeding curlews

and an increased breeding snipe

population. If a productive population

becomes established, then young

curlews could repopulate some of

the other islands and mainland sites

around Lower Lough Erne, bringing

the bubbling sounds of spring to a

much wider audience once more.

Brad

Robson

Brad

Robson

We manage our Western Atlantic oakwoods for

pied flycatchers and other summer migrants.

The wet meadows with naturally undulating topography generate softground conditions and a large amount of invertebrate prey throughoutthe breeding season.

By 2010 nesting habitat for curlews andsnipe had deteriorated due to scrubencroachment and rush infestation.

Exposed limestone and shallow soilsat the eastern end of the island are richin vascular plants and invertebrates.

Brad Robson

and from Fermanagh District Council

to remove 2 ha of invasive alder, birch

and blackthorn scrub from the

island’s meadows, to flail a further 2

ha of bramble and gorse and to

remove 2 km of field boundary trees

to recreate nearly 20 ha of

unimpeded open meadows.

Work began in October 2011, with

local contractors flailing bramble and

gorse using low ground pressure

machinery to minimise the impact on

the sward and soils. The standing

trees were all injected with undiluted

glyphosate by reserve staff in autumn

31SAV ING NATURE

Brad

Robson

Low density cattle grazing fromApril to December creates suitableconditions for both nestingcurlews and a high diversity offlowering plants.

Thanks to:This project has been supported by

SWARD through the NI Rural

Development Programme, Fermanagh

District Council and the Northern

Ireland Environment Agency.

ReferencesPartridge JK. (1988). Breeding waders

in Northern Ireland. RSPB

Conservation Review 2:69-71.

Stanbury A, O’Brien M and Donaghy

A. (2000). Trends in breeding wader

populations in key areas within

Northern Ireland between 1986 and

2000. Irish Birds, 6, 513-526.

Orkney is a very special place, containing high densities of

breeding hen harriers, amazing seabird colonies and

archaeology, and still hosting good numbers of farmland

birds. In this article we describe some of the special

features of the birdlife of Orkney, and what we are doing

to help maintain its unique bird life – crucial for an area

where so many of the visitors come to enjoy the natural

environment.

ANDY KNIGHT, ORKNEY RESERVES MANAGER

Our amazing Orkney reserves

Numbers of hen harriers have recovered well, with RSPB nature reservescurrently holding a third of the Orkney population.

32

Mark H

amblin (rsp

b-images.co

m)

33S AV I N G N AT U R E

The RSPB manages 13 nature

reserves on Orkney, covering 8,439 ha.

The majority of their area comprises

upland heath and montane habitat,

together with smaller areas of

marginal and agriculturally improved

farmland, wetland and a range of

coastal habitats. Our nature reserves

contain 41 known archaeological

features, including six Scheduled

Ancient Monuments.

Management of the RSPB’s nature reserves on OrkneyAbout a third of the area of our nature reserves is open to grazing. Our reserves

support five common grazings, and 21 grazing lets. This arrangement provides

benefits to local farmers and contractors (see also the article on pages 22–23).

In terms of management of all of these habitats, there has been a general

move towards more of a landscape scale approach. It has become increasingly

important to incorporate management on nature reserves with advisory and

advocacy work outside reserves. Reserve boundaries blur more into the

countryside outside these days – this applies to management of moorland,

arable, farmland and wetland habitats. Management for corncrakes, waders and

songbirds is all combined into integrated farmland bird management.

For farmland and wetland habitats, agri-environment agreements have been

important in supporting grazing of hard to graze wader habitats, the use of

specialist cutting equipment, and delayed mowing for corncrakes.

0

5

10

15

30

Year

Nu

mb

er o

f ap

par

entl

y o

ccu

pie

d t

erri

tori

es

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

20

25

In ornithological terms, Orkney is

perhaps best known for its hen

harriers (as well as Eddie Balfour who

studied hen harriers on Orkney in the

1950s) and seabirds. Harrier numbers

declined from their 1970s heyday to

just 30 territories in the early 1990s.

This prompted an RSPB-sponsored

study into the causes of this decline.

The study linked the decline of hen

harriers to low availability of their main

prey, Orkney voles, in late winter and

early spring. This low food availability

was itself correlated with high

numbers of sheep, whose intensive

Numbers of hen harrier apparently occupied territories on the RSPB’s Orkney West

Mainland reserves

grazing reduced the area of ranker

grassland in which the voles live. Bad

weather in spring also has a negative

impact and accounted for annual

variations in productivity. A

combination of reserve management,

the Natura 2000 Hen Harrier Scheme

and agri-environment schemes

encouraging reduced sheep stocking

on hill land, has resulted in a stunning

recovery of hen harriers back to the

levels seen in the 1970s. In 2011, there

were 103 sites occupied by hen

harriers on Orkney, 37 of which were

on RSPB nature reserves.

The situation regarding seabirds

remains of high concern. For example,

34 SAV ING NATURE

numbers of seabirds at Marwick Head

have declined by 53% since Seabird

2000, and by a further 22% since

2006. The situation has vividly struck

home to fieldworkers, who now visit

productivity monitoring plots that no

longer have any birds in them. Despite

these declines, the seabird spectacles

at Noup Cliffs, Marwick Head and

Copinsay still remain impressive. The

spectacle at Noup Cliffs is heightened

by its burgeoning gannet population.

Gannets first bred in 2000 and there

are now 600 nests. Puffins, black

guillemots (tysties), great skuas and

red-throated divers have not suffered

the big declines or fluxes of the other

seabirds. Research is being carried out

to increase our understanding of

seabird feeding behaviour to help

identify the location of important

seabird feeding areas, and the

potential effects of marine renewable

energy developments (see boxes). �

Orkney is also becoming one of those

ever decreasing places where

farmland birds (perhaps still taken for

granted by us locally) are a feature for

visitors, with large numbers of

curlews, lapwings and skylarks, birds

once regarded as typical of many

areas of farmland on the mainland.

RSPB sites contribute significantly to

this, achieving wader densities of two

pairs per hectare on wetland habitats

such as at the Loons, and one pair per

hectare on farmland mosaic habitats

such as at Onziebust. Most reserve

wader populations have increased or

remained stable, but moorland-

breeding curlews are showing signs

of a decline. The reasons for this are

unclear, but we are focusing on

adjusting our grazing, cutting and

burning management to try to ensure

that we cater for their requirements.

Tracking bonxies on Hoy

The movements and foraging behaviour of great

skuas – also known as “bonxies” – are being

tracked on Hoy by Helen Wade, from North

Highland College – University of the Highlands and Islands. The aim of this

research is to increase our understanding of the potential effects of marine

renewable energy developments on this species.

Initial findings show that during the breeding season some individuals

undertake foraging trips of more than 1,300 km, travelling farther north than

the Faroe Islands. The average foraging trip, however, was 85 km, with birds

making trips to the Caithness coast and down to the Moray Firth.

Continuing FAME

FAME – Future of the Atlantic Marine Environment –

is a project to monitor and track seabirds across the

western seaboard of Europe, in order to help us

understand their feeding behaviour.

We had a really successful year tagging seabirds in Orkney in 2011. This

allowed us to see if the long journeys that some birds were making in 2010

were unusual. In 2011, some birds again travelled long distances to find

suitable feeding areas, as did their neighbours on Fair Isle.

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)

Mark Sisson (rspb-images.com)

Movements of breeding razorbills from Orkney in 2010 (left) and 2011 (right).

Further details of FAME can be found in RSPB Reserves 2011 or at

www.rspb.org.uk/FAME.

35SAV ING NATURE

Thanks to:Tracking of bonxies

was funded by the

Marine Renewable

Energy and the

Environment

(MaREE) project,

European Regional

Development Fund,

Highlands and

Islands Enterprise,

Scottish Funding

Council, British Trust

for Ornithology

(BTO), Department

of Energy and

Climate Change

(DECC).

FAME is 65%

funded by the

European Regional

Development Fund

Atlantic Area

Transnational

Programme.

Orkney Reserve SnippetsHoy – 3,962 ha of mountain and moor, home to Britain’s

most northerly native woodland. A new (to Orkney) UKBAP

solitary bee species, the tormentil mining bee Andrena

tarsata was found this year, and has since been evaluated

as one of the largest aggregations now known in the UK.

Brodgar – surrounds the famous stone circle, the Ring of

Brodgar, part of the Heart of Neolithic Orkney World

Heritage Site. A great short walk with skylarks and

farmland waders for company. An easy place to see the

rare great yellow bumble bee in August.

The Loons – a great wetland with great views of wetland

birds all year round, brilliant for water rails in the early

Autumn.

Marwick and Noup – the classic seabird cities in the most

magnificent of seascapes.

RSPB nature reserves on Orkney

Mainland Moors (Birsay Moors, Hobbister and Rendall

Moss and Cottascarth) – for the best views of nesting

red-throated divers, and the core of the hen harrier

population.

Mill Dam – a jewel of a wetland, with our favourite hide

providing an almost aerial view over the reserve. Great at

any time of the year.

North Hill on Papa Westray – a coastal heath supporting

skuas and the enigmatic Scottish primrose.

Trumland – a hearty walk rewards with stunning views

across Orkney between ducking bonxies.

Onziebust – principally managed for corncrakes, this reserve

surprises most people with its abundance of farmland

waders, skylarks and botanically species-rich meadows.

Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyrightand database right 2012.

RSPB nature reserves are home to more than 15,000 species.

Here are some of the rarest, found in only a few places in

Britain. From high mountain tops to coastal marshes, our

nature reserves are important refuges for these plants,

animals, and fungi. Some may be the last survivors from

ancient times, living archaeology that can tell us about our

past. Others may be the vanguard of lost species that are

trying to return. Although some seem always to have been

rare, others have now retreated to nature reserves as their

habitat has been lost from the countryside.

MARK GURNEY, RESERVES ECOLOGIST

Meet some of our special species

36

Tim Strudwick

The mason wasp Odynerus simillimus is a globally rare species found on RSPB nature reserves.

It catches weevil larvae and brings them down its chimney.

37SAV ING NATURE

From Scotland to theHimalayas with only one stopJoergensen’s notchwort

Anastrophyllum joergensenii lives

under heather on boulder covered

slopes at Abernethy. It is a rare

species, found at a few other places

in the Cairngorms and north-west

Scotland. Its nearest neighbours are

across the North Sea on a mountain

in the rugged Fjordlands of southern

Norway, but the only other

populations of this liverwort are

thousands of miles away in the

majestic peaks of the Himalayas.

Traveller in time or space?Issler's clubmoss Diphasiastrum

issleri is an enigma. It is of hybrid

origin, and while one of its ancestors,

Alpine clubmoss Diphasiastrum

alpinum is a common plant in the

uplands of Britain, the other,

Diphasiastrum complanatum, has

never been found here. How can two

plants that have never met leave their

progeny growing in a steep valley at

our Abernethy reserve in Scotland?

Perhaps fine spores have been

carried on the wind across the sea

from one of the areas where

Diphasiastrum issleri grows on the

continent with both its parents. Or

perhaps Diphasiastrum complanatum

once grew in Scotland but became

extinct as the climate and landscape

changed, leaving its genes in Issler's

clubmoss as a time capsule and the

only reminder that it was ever here.

Snake in the grassDespite its English name, viper's-

grass Scorzonera humilis is a

member of the daisy family, with

yellow flowers like a dandelion. Noel

Sandwith added this plant to the

British flora when he was only 12

years old, and he was rewarded with

a day off school to show the plant to

the doyen of British botany a couple

of years later. Viper's-grass still grows

in the field at our Wareham Meadows

reserve, which has the only large