Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

Transcript of Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

1/19

JOURNAL OF URBAN ECONOMICS 2, 85-103 (1975)

Racism and Urban Structure ISUSAN ROSE-ACKERMAN

Institution for Social and Policy Studies and Department of Economics,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520Received October 12. 1973

This paper begins the task of integrating models of racist behavior into generaltheories of urban land use. The paper derives equilibrium prices for a racist cityand demonstrates that the city is less dense at the core, more dense in the suburbs,and covers a larger area than an unprejudiced city. A more complex theory ofhousing supply is then developed, and it is shown that racisms impact on theghetto depends upon the ease with which maintenance can be reduced, the costof replacing abandoned housing, and the nature of legal controls on housingquality.I. INTRODUCTION

With few exceptions, economic analyses of racial discrimination in housingmarkets have not been systematically integrated into a theory of urban struc-ture and land use.2 ndeed, much of the literature assumeswithout sustainedanalysis that blacks pay more for housing because prejudice restricts supplyand simply attempts to estimate the size of the price mark-up. Richard Muth[ 12, pp. 106-l 121, following a suggestion of Martin Bailey [2], has madeone of the few attempts to develop a logically consistent model of the demandside of a racist housing market.3 Using this model, Muth argues that racialprejudice lowers the price of housing available to blacks. Muth, however,fails to consider explicitly how suppliers respond to racial prejudice and henceignores racisms broader consequencesupon the distribution and density ofthe urban population. The first half of this paper (Sections II-IV) formalizesMuths theory of racist behavior in the context of a general urban housing

1This paper was financed by NSF Grant No. GS-39,671. The author thanks BruceAckerman, Edwin Mills, Richard Muth and Robert Pollak for helpful comments on anearlier draft.2The exceptions stress the importance of housing market discrimination in restrictingthe employment choices of blacks. See [5] and [B].3 Muths theory of racial discrimination is not the only one which is plausible. Othertheoretical attempts that take a different perspective include [3], [7], [15], [16], and [17].For empirical work that is closely related to Muths model see [9] and [lo].

85Copyright 0 1975 by Academic Press. Inc.All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

2/19

86 SUSAN ROSE ACKERMANmodel of the type commonly used in recent work. After showing how theprice-distance function for housing is affected by racial prejudice, the paperdemonstrates that a prejudiced city is less dense at the core, more dense inthe suburbs and covers a larger area than its unbigoted counterpart. In thesecond half of the paper (Sections V and VI), a model is developed whichtakes into account the fact that most of the housing stock consists of oldunits depreciating over time. This model makes it possible to refine the analy-sis of supplier behavior and to discuss the impact of racism on the density,quality and price levels of housing in the ghetto. Two variants of the modelare compared-one in which maintenance can be varied and one in which ahousing code determines the maintenance inputs required. It is shown thatwhen the law requires suppliers to maintain a minimum level of housingservices, blacks gain more from prejudice than when suppliers are free toadjust maintenance levels or abandon properties.

II. THE MUTH FRAMEWORKMuths model (like all other theoretical discussions of racial prejudice)assumes that bigotry per se has no impact upon the supply of housing. Hisdemand oriented model focuses upon two types of people: whites who havean aversion to living near blacks and blacks who do not care where they live.4Thus, whites bid more than blacks for housing in predominantly white areas,leading to two racially distinct neighborhoods with a common border. Exceptalong the black-white border the black neighborhood is assumed to besurrounded by land that cannot be used for housing. If quality adjustedhousing prices are initially equal in the interior of the white and black neigh-borhoods, blacks can outbid whites along the border. If landlords are profitmaximizers, and if there are no costs of converting housing from white toblack use and no collusion, housing changes hands and the border movesaway from the center of the black neighborhood until the prices that blacksand whites are willing to pay are equal at the border. In equilibrium, whenprices are equal at the border, white interior prices must be higher than whiteborder prices since whites prefer to be surrounded by households of theirown race. It follows that rents in the black neighborhood are lower than in thewhite interior, and lower also than equilibrium prices in the absence ofprejudice.

III. A MODEL OF THE HOUSING MARKET WITHNO RACIAL PREJUDICEIn the present section, a simple model of the housing market in an un-prejudiced city is developed to provide the groundwork for introducingracism in Section IV.4 One could also assume, as Muth does [12, p. 1081, that blacks prefer to live next towhites, but this assumption is not necessary if the black market area is restricted.

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

3/19

RACISM AND URBAN STRUCTURE 87A. Demand

The simple model explicated here uses some standard assumptions em-ployed by many workers in the field and exemplified in [12]. Thus it is as-sumed that a households utility level depends upon its consumption of twomutually exclusive groups of commodities-housing and all other goodsexcept location; that the prices of other goods do not vary by location; thatthe variable cost of transport increasesat a nonincreasing rate with distancefrom the central business district (CBD); that each household makes a fixednumber of trips to and from the CBD per unit of time; that transport costsare the same n all directions, and that all jobs are located in the CBD withina small circle of radius v miles.5 If housing services per unit of time can berepresented by a single variable, q, that is a weighted average of housingattributesfi then the individual household chooses ts residential location bymaximizing its utility function U = L/(x, q) subject to the constraintx + p(k)q + w, y) - y = 0.

whereX = spending per unit of time on all commodities except housing andtransportation but including leisure.4 = consumption of housing per unit of time.k = distance from V, the boundary of the CBD. Transportation isassumed o be costless within the CBD.p(k) = price per unit of housing at k.T = cost of travel to and from the CBD per unit of time, Tk > 0,(T includes both out-of-pocket costs and the opportunity costof time).Y = income per unit of time.

The maximum occurs whereand Uz = U,/p(k) (1)

- pk = Tn or pk = (- l/q)T, < 0. (2)In order for an equilibrium to exist, the price of housing must fall with dis-tance, and stability requires that -qpk fall more rapidly then Tk. Otherwise,households could benefit from moving either closer to or further from thecity [12, pp. 24-251.

6 Muth [12, pp. 17-211 drops some of these simplifying assumptions in later portions ofhis book, but these modifications will not concern us here.6This formulation follows Mills [ll, p. 2011 and Muth [12, pp. 18-191.7 Muth [12, pp. 21-221. The following paragraph reproduces Muths results for readersunfamiliar with his work. Muths formulation differs from the slightly more complex modelof Alonso [l] where distance, k, enters the utility function directly.

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

4/19

88 SUSAN ROSE~ACKERMAN

The supply side is also derived from Muth [12, pp. 47-491 and is a simplecompetitive market in which all housing inputs are variable. Suppliers ateach k combine three inputs: land, L, structural inputs, S, and maintenanceinputs, M, in order to produce housing. Housing is not divided into discreteunits, so that supplier i located at distance k can costlessly subdivide thetotal @(k) he supplies to provide any q(k) desired by an individual household.All land beyond v is zoned for residential or agricultural use. Since there areno alternative uses or land beyond v except farming, profits per unit of timefor producer i at k arez-i(k) = p(k)Qi(k) - r@&(k) - s&(k) - mMi(k),so long as r(k) > Pwhere

(3)

Qi(k) = Q&W), S(k), M(W),r(k) = land rent per acre at k,p = maximum rent per acre obtainable from agriculture,s = price of structural inputs, andm = price of maintenance inputs.The prices ?, s, and m are independent of k. Producers maximize profits byequating the price of each factor to the value of its marginal product. Hence,

r(k) = Ak)QL,, (da)m = p(k)QM,, (4b)s = p(k)Qsi. (4c)

Where QL~, QM~and Q,si are the marginal products to the ith producer ofL, M, and S, respectively. In a competitive market profits must be equal forproducers at all k, a fact which, as Muth has shown in a similar model[12, p. 491, makes it possible to specify the relationship between land rentand housing price as

rk/r = (dPL)(Pk/p), where pi = lands share. (5)C. Market Equilibrium: Incomes Equal

Market equilibrium occurs when total demand for housing equals thetotal supply. This equilibrium can be specified f strong assumptions are madeabout consumers. If the number of workers is exogenous, if every householdcontains a single worker, and if all households have equal incomes and iden-tical tastes, then the equilibrium price at each k must be one such that house-holds are indifferent between ocations. If pi(k) is the pattern of prices which

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

5/19

RACISM AND URBAN STRUCTURE 89would prevail if consumers attain utility level Uj, then the housing demandedby each household at k, qj(k), is uniquely determined. Every household hasa family of bid-rent lines pi(k) with pk < 0, each corresponding to a differentlevel of utility. (The higher is pj(k) the lower is utility).8The supply of housing at k when pj(k) represents he market price is

where Qij(k) is the quantity supplied by the ith producer at distance kgivenpi(k), and nk is the number of producers at k. The maximum number ofhouseholds that can be accommodatedat any k is then, Ni(k) = (Qj(k)/qj(k)).Assuming that i& is the distance at which rj(L) = P when pi(k) holds, themaximum number of households that can be accommodated for somepi(k) is

sLjNj = Nj(k)dk.

0

Equilibrium in the housing market occurs for pi(k) such that H = Nj whereH = number of households. If H > Nj, there is excess demand and pj(k)must rise and conversely, for H < Nj.

IV. RACIAL PREJUDICE IN THE HOUSING MARKETA. The Location of Blacks in a City Without Prejudice

In order to introduce racial prejudice into the model it is necessary tospecify the behavior of black households in a city with unprejudiced whites.The notion of a city without prejudice is, however, ambiguous. On the onehand, if no prejudice has ever existed in any area in life, and if blacks andwhites are equally productive, members of both races have equal incomes, andso long as they have equivalent tastes, blacks are distributed randomlythroughout the housing stock. On the other hand, if blacks are discriminatedagainst in education and in jobs but not in the housing market, they havelower average incomes and hence trade off accessibility and housing differ-ently from whites.The impact of introducing prejudice in the housing market differs in eachcase. In the first case since black income levels equal white levels, Muthsanalysis implies that blacks occupy a self-contained section of the city whichcould be either a pie shaped wedge or an annulus. Blacks, however, paylower rents at each distance than whites living at the samedistance but locatedin the white interior. Although blacks are indifferent to the location of their

8The best discussion of bid-rent lines is found in Alonso [l].

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

6/19

90 SUSAN ROSGACKERMANself-contained neighborhood, whites prefer to have blacks living in a ringaround the CBD in order to minimize the length of the black-white border.

In the second case, even if the tastes of blacks and whites are identical,blacks have different bid-rent functions from whites because of the blackslower income. Empirical work indicates that the income elasticity of thedemand for housing is greater than one9 which, under plausible assumptions,implies that the bid-rent functions of the wealthy are flatter (i.e., the absolutevalue of the slope is lower) than those of the poor [12. p. 291. As a conse-quence, the blacks, because of their relative poverty, would live closer to thecenter of the city than the whites. Hence blacks occupy a compact section ofthe city even if no prejudice exists in the housing market. When white pre-judice is introduced, the black neighborhood includes additional housing atthe border between the black and white neighborhoods. In this paper it isassumed that blacks would live in the city center even if no prejudice existedin the housing market. Such an assumption is reasonable since average blackincome levels are lower than those of whites, with the difference plausiblyattributed to discrimination in education and jobs.B. Market Equilibrium with Lower Class Blacks

(1) The unprejudiced city. In an unprejudiced city where low income blacksoccupy the city center, the equilibrium pattern of prices can be determined ina simple manner. Given any bid-rent curve for blacks, pj(k), with corre-sponding household demands, q,R(k), and housing supplies, Qj(k), we have:Nj(k) = Q,(k)/qJR(k), where N,R(k) is the number of black householdsthat can be accommodated at k. Given H, the total number of black house-holds, the edge of the black neighborhood is at bj (where bj is measured inmiles from the border of the CBD) such that

Jbi

H = NiB(k)dk.0Let pjW(k) be the white bid-rent function that passes through [bj, pjB(bj)].This bid-rent function implies a particular qJU3(k),Qj(k) and Nj(k) = Q j(k)/q(k) for each k > bj. Because of higher white incomes, white demand isgreater at any price than black demand, and therefore density of settlementfalls discontinuously at the black-white border. Letting

.IiiNjw = Njlli(k)dk,bj

and P = number of white households, the bid-rent lines pjB(k), pj(k) are9 Muth [ 131 and Reid [ 141 find income elasticities between one and two. Not all wealthyhouseholds, however, have a high income elasticity of demand. See [4].

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

7/19

RACISM AND URBAN STRUCTURE 91the equilibrium price lines if NjzL Hw. If Njw > Hw, excess supply existsand p(k) and pB(k) must fall (b must rise) to establish equilibrium. Con-versely, if Njw < Hw excessdemand exists and prices must rise (b will fall).(2) The racist city. If white households are prejudiced, they are both at-tracted to and repelled from the CBD. Although the utility function for blackshas the same form as that assumed above, UB = .P(x, q), whites utilityfunctions include the distance to the black-white border as an argument:Uw = Uw(x, q, k - b). The whites budget constraint is

x + p(klq + T(k, v) - Y = 0.Maximizing Uw subject to the budget constraint yields

uz = uq/P = Uk-b/(pkq + Tk), (6)orpk = - Tdq + [Uk-b/Uz]/q. (7)

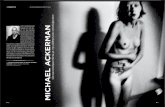

Since U&-b > 0 and U, > 0, prices in the white neighborhood fall moreslowly than in the unprejudiced city and may even rise with k over a certainrange beyond the black-white border. Ifpk > 0 at b, then white prices ncreasewith k until Tk = uk-b/uz. Beyond this point they fall with k, approachingthe rate of change of white housing prices in an unprejudiced city so long asthe marginal utility of moving an extra mile away from the black-whiteborder falls as k increases. f p?(k), pow(k), and b. in Fig. 1are the equilibriumprice lines and border with no prejudice and if poR(k) is the price schedulefor prejudiced whites such that at bo, poR(bo) = poB(bo) = pow(bo), thenNoR > Hw i.e., there is excesssupply ifpoR(k) holds, and equilibrium can onlybe established through a fall in pB(k) and pR(k) and an increase n b to accom-modate the increased black demand. The equilibrium white bid-rent function,

I Ib., kFIGIJRE 1.

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

8/19

92 SUSAN ROSE- ACKERMANp ik,

FIGURE 2.

plR(k) in Fig. 2, cannot, however, be below p,,(k) for all k or else NIR < Hw.Therefore, plR(k) must cross pow(k) at some point, kr, and racist whites paylower prices in border regions than whites in a city without prejudice, but payhigher prices in outlying areas. The price difference between a racist and anonracist city is larger the more intense is white prejudice and the moreslowly Uk-,, falls with distance from the border.It follows that the area of a racist city is larger than that of a nonracist onesince the higher equilibrium level of housing prices beyond kl in a prejudicedcity implies that f is greater.OFurthermore density is lower in the ghetto ofa racist city and also in the white area between bl and kl, but is higher inthe white suburbs beyond kl, since prices are lower in the first two regionsand higher in the third. Density between b. and b1 is likely to be higher aswell because of the shift from high income white to lower income blackoccupancy. However, the population could be less concentrated in this regionif blacks have a very high elasticity of demand for housing, or have incomesclose to white levels and if prices are much below those that would prevailin an unprejudiced city.

i If the production function is Cobb-Douglas, the price of housing, p, where r(lr) = i is in-dependent of the particular bid-rent line which prevails. Let Q,(k)=ao~,(k)Uls,(k)lM,(k)3where al + ap + a3 = I. Solving for the marginal products of L, S and M, and substitutingin 4a, b and c, gives expressions for p(k), S&r) and M,(k). Substituting for Si and Mi inQi and for Qi m p(k), we obtainP(k) = (.,,~~:,::.~:~,,.,,,)r(k~l.

I* (5) implies that land rents follow the same pattern as housing prices. They rise if p(k)rises and fall i f pH(k) falls. However, the land rent gradient is steeper than the housing pricegradient and is steeper the smaller is lands share in producers revenues.

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

9/19

RACISM AND URBAN STRUCTURE 93V. A MORE SOPHISTICATED MODEL OF THE HOUSING MARKETA. Introduction

The racist city was introduced in Section IV, using a simple model in whichall housing inputs are variable. At any point in time, however, most of thestructural characteristics of the housing stock are fixed by earlier constructiondecisions.12 Thus owners of older housing are faced with the choice of varyingmaintenance levels, demolishing their buildings, or abandoning their property.If these facts are taken into account, the magnitude of the price benefits ob-tained by blacks depends upon the ease with which suppliers can react tolower prices by spending less on maintenance or by abandoning unprofitableunits. To make this point precise, this section presents a model of the behaviorof owners of old housing in a city without prejudice. Prejudice is introducedinto the model in Section VI.

To develop the problem further, the operation of the housing market willbe considered under two hypotheses about supplier behavior. First, ownersare assumed to be legally permitted to reduce maintenance levels in any waythat maximizes profits. Second, the existence of a housing code is posited,requiring landlords to maintain quality despite the aging of their housingunits. It is then possible to define the conditions under which a legal effortto maintain housing quality redounds to the advantage of blacks. Throughoutthe discussion an effort is made to show how consideration of the existinghousing stock modifies the earlier results using a more conventional supplymodel.B. Basic Assumptions

In order to contrast a housing code model with one in which maintenancecan be varied, a general framework is required for dealing with a housingstock composed principally of old structures. In the model developed belowthe age of dwelling units falls with distance from the CBD. The city is assumedto consist of a central circle containing all jobs surrounded by a series ofrings, each ring containing housing built in a particular year. No vacantland exists except in the urban fringe beyond some distance k*. There aretwo groups of suppliers: landlords owning existing housing who (unlessprevented by law) choose the level of maintenance that maximizes profits, andbuilders of new housing who operate beyond k*. All producers have Cobb-Douglas production functions for housing services in the three inputs:

I2 Long run equilibrium models such as those developed by Mills [I I] and Muth [12] donot deal explicitly with the existing housing stock. The fullest current consideration ofexisting supply is found in the urban simulation model in [6].

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

10/19

94 SUSAN ROSE-ACKERMANL, S, and M. Output at time t for producer i at k is

Q,(k, t) = aoLi(k)ulS,(k)az(k,Mi(k, t)as. (8)Producers of new housing at k > k* have identical constant returns to scale(CRTS) production functions where & = 1 - aI - a:+ Owners of old hous-ing have decreasing returns to scale production functions where al + az(k)+ u3 < 1. The exponent on S(k), an(k), depends upon the age of the struc-ture and falls as age ncreases.Since age and distance are inversely correlated,this implies duZ/dk > 0. Producers of new housing maximize the discountedpresent value of profits. Since L and S must be fixed when the housing isbuilt, if we assume that payments to L and S continue over time and thatbuilders expect all prices to remain constant, the present value of profits toproducer i at k is;13

sccri(k) = p(k)Qi(k,t)eewldt - (rLi(k) + sSi(k)),!w

0

im-m Mi(k,t)e-wtdt, (9)

0

where w = the interest rate.C. The Variable Maintenance Model

1. Profit maximizing conditions. Equilibrium conditions can now bespecified for builders of new homes and for owners of older structures whenlandlords are permitted to vary maintenance to maximize profits.First, consider new construction. Builders beyond k* maximize (9) withrespect to (8). This maximum occurs whereQi(k,t)eewtdt - * = 0,W

u2(t)Q,(k,t)e-wtdt - = 0,W

~&)Qi(k,t>~i(k,t) - m = 0 for all t.

Wa)

(lk)Owners of old housing, however, need only consider returns in the currenttime period if demolition and new construction are assumed o be impossible.Since S and L are fixed, landlords maximize profits where (IOc) holds forI3We ignorehere he question f the optimal ife of a housingunit.

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

11/19

RACISM AND URBAN STRUCTURE 95t = 0. Equation (1Oc) implies that Mi(k) is an increasing function of p(k).This can be proved by substituting for Qi(k) from (8) and solving for Mi(k):

[a3a1 1/a3M,(k)-p(k)Li(k)"hsi(kp(")m (11)

The partial derivative of Mi(k) with respect to p(k) is obviously positive.Having specified the landlords profit maximizing expenditure on main-tenance, the returns to L can be determined given that the returns to S arefixed at s&(k). If vigorous competition prevails throughout the housingmarket so that profits are forced to zero on all housing, the returns to land arer(k)L;(k) = (1 - a&(k)Q@) - LX(~). (12)

2. The rate of change of land rent. Since land is not necessarily paid thevalue of its marginal product, the relationship between and rents and housingprices is more complicated than in the conventional model presented inSection II.From (12)

Hence,r(k) = (1 - a )p(keo - sick>3

L(k) L(k)

Andrk = (1 _ a3)[ IpkG + p(k$L] - $?!?.dk dk

rk Pk- = (1 - a:

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

12/19

96 SUSAN ROSE-ACKERMANall fixed costs only occurs if the required payments to S are so large as tomore than exhaust the revenue remaining after maintenance expenses havebeen paid. In this case nonnegative profits can only be obtained with r(k) < 0.This can occur ifp(k) has fallen over time so payments to S, are large relativeto what they would be if the housing were newly built.Even before the abandonment point is reached, however, landowners mayinduce the owners of older housing to demolish their structures and buildnew ones. If demolition is inexpensive enough, landowners create incentivesfor new construction by raising land rents to the level that would be obtainableif demolition occurred. If D is the cost of demolition per unit of land, thenlandowners set rents atr(k) = max[z [ Qi(k,t)e-J%i9 - D\rv,

Qt(k,O) s&(k)(1 - ns)p(k)- L(k) 1i(k) (14)where QQ is the profit maximizing quantity of new housing. and Q* is thecorresponding quantity of old housing.4. Equilibrium. Given the quantity supplied for every p/(k), pjtc(k) whenover all profits are zero, equilibrium in this model is established in the sameway as the conventional one (Section IV B(l)), except that new housing isonly built beyond k* on land such that r(k) < F. If total demand grows withthe passage of time because population or income increases, the equilibriumprice line must rise over time, with new construction occurring at the fringesof the urban region. Thus, assuming that no vacant land exists in the interiorand that demolition-followed-by-new-construction is not profitable, themodel generates a pattern of construction over time that is consistent withthe earlier assumption of an inverse correlation between age and distancefrom the CBD.D. The Housing Code Model

Assume now that a housing code requires owners to provide a minimumlevel of Q even though profits are maximized at lower maintanence levels.To introduce this housing code model, assume that owners are forbiddento abandon their properties and are required to compensate for the fallingproductivity of structural inputs by a corresponding increase in M so thatQi(k, t) 2 &i(k) for k 5 k*, where &(k) is the level of housing output pro-vided when the unit was new. Landlords are required to substitute M for Sas housing ages in order to maintain this minimum Q. Similarly, new con-struction can occur beyond k* as a means of establishing market equilibrium.If producers of new housing assume that the housing code will be in force in

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

13/19

RACISM AND URBAN STRUCTURE 97the future, then given

Mi(k,/) =ao~i(k)alSi(k)zc l/o3~ 1i(k) their profits are maximized where

ulp(k)!i(k) - r(k) = 0,L(k) Wa)

s

maxp(k) &i(k) Mi(k,t)-e-dt - 2 = 0. (15c)

0 W

Since this model is identical to the variable supply version when Ql(k)> Qi(k), it is only necessary to consider the case in which the housing codeis binding. When no racial prejudice exists but blacks have lower incomes thanwhites, the equilibrium bid-rent lines for the housing code model must bebelow the equilibrium bid-rent lines when M is variable because &(k) > Q(k)for all k < k* and hence, if prices were not lower under the housing codemodel, supply would outstrip demand. l4If, however, code enforcement generates abandonment, prices may behigher under a housing code model, especially when the negative externalitiesgenerated by vacant dwellings are taken into account. If housing adjoiningabandoned housing is judged by households to provide a fraction of thehousing services provided by other housing, then if housing at k - e isabandoned, e a small number, the quantity of housing at k becomes A&(k),0 < X < 1. If X is low enough i.e., if the externalities generated by vacantunits are high, then, in equilibrium, housing at k may be abandoned alsobecause the M(k) that would provide zero profits is less the A4 required toproduce &(k) units of housing.Of course, if the cost of demolition is low enough, the externalities ofabandonment may be eliminated by new construction. This occurs if the r(k)that satisfies

wag(k) .=r(k) = ~- J,(k) oQt(k,t)e-Wt - Dw

is greater than or equal to zero.I4 While black and white tenants will pay less for each unit o f housing service, they maypay more or less for each unit of srructural input provided (measured, for example, as rentper square foot).

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

14/19

98 SUSAN ROSE ACKERMANRegardless of whether housing codes generate higher or lower prices, theyinduce a pattern of settlement that is different from that prevailing under the

variable supply model. When M is variable, blacks live in housing with higherratios of L and S to M relative to the ratios than would obtain with fixed Q.Moreover, when code enforcement generates abandonment, regions close tothe CBD are vacant while blacks are densely settled in the adjoining sector inold housing with relatively high levels of maintenance.VI. THE IMPACT OF RACISM IN A CITY WITH ANAGING HOUSING STOCK

A. Variable SupplyWhen landlords can vary M, the magnitude of the price benefits obtainedby blacks from racial prejudice depends upon the price elasticity of main-tenance spending for older housing in ghetto and border regions. The morelandlords reduce maintenance in response to lower prices the less differencethere is between the equilibrium bid-rent lines for blacks with and withoutracism.The shape of the equilibrium bid-rent lines is the same as those under thesimple supply model (e.g., pP(k), plR(k) in Fig. 2). In the present case,

however, new construction only occurs between k* and L1. The ratios of Land S to M are higher than those prevailing in the simple supply model, butthe basic result is analogous: less supply in the central section and more inthe suburbs. Speaking more loosely, under the variable supply modelracism leads to lower quality housing in the ghetto as well as lower pricesper unit of both Q and space.B. Housing Codes

When housing codes require landlords either to maintain Q(k) at some fixedlevel &(k) or to abandon their property, the price benefits of racism are smallerthe higher the cost of maintaining old housing to code levels, the greater theexpense of demolishing old units and replacing them with new construction,and the larger the externalities from abandoned units. The shape of theequilibrium bid-rent lines will be the same as pP(k), plR(k), but there maybe a zone of empty houses close to the CBD.C. Variable Supply and Housing Codes Compared

While it is relatively easy to demonstrate that blacks pay less for housingwhen racism exists in either the variable supply or housing code model, asecond issue requires a more sustained argument. This section specifies theconditions under which housing code enforcement generates a larger welfare

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

15/19

RACISM AND URBAN STRUCTURE 99gain for black tenants than a free market regime under which landlords arefree to vary maintenance. The argument proceeds n three stages.First, it isdemonstrated that, when abandonment does not occur, equilibrium utilitylevels under a housing code cannot be equivalent to those that prevail underthe variable supply model. Second, it is shown that, in the absence ofabandonment, blacks in a racist city are almost certain to be better offunder a regime of housing code enforcement while whites could be worseoff. Third, if abandonment with its accompanying externalities occurs, thenno definitive welfare statements are possible.1. The nonequivalenceof equilibrium in the two models. Assume that plB(k)and plR(k) in Fig. 3 are the equilibrium bid-rent lines under the variablesupply model. To prove that the utility levels representedby these price linescannot be the ones prevailing in equilibrium under a housing code model whenno abandonment occurs, this section assumes hat the contrary holds anddemonstrates that a contradiction exists.Imagine, then, thatplB(k) is also the equilibrium bid-rent line in the housingcode model. Since abandonment does not occur, Ql(k) < &(k) for k < bl.Therefore, with code enforcement, total black demand can be accommodatedbetween the border of the CBD and some b2 where bz < bl.Consider now the white bid-rent line that passes hrough b2 which giveswhites the same evel of utility as plR(k). This bid-rent line, pzR(k) in Fig. 3,is above plR(k) for all k since at every k blacks are further away.Given these bid-rent lines it is possible to establish the contradiction in-volved in assuming that plB(k) and p&k) establish equilibrium prices inthe housing code model. Beyond bl, supply to whites under the housing codemodel is greater than under the variable supply model since the existence ofthe housing code implies that &(k) 2 Ql(k) for k < k* and since the higherprices beyond k* induce more new construction. White demand, however,

P k)

I Ib, b, k k, i,

FIGURE 3.

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

16/19

loo SUSAN ROSE--ACKERMANis lower at every k > 61.: Hence the total white population, H, could beaccommodated between hl and some k < k,. Therefore, the contradictionis established: either pi(k) or p2R(k) or both must shift to establish equi-librium at some p,:(k), p,(k) where am = plK(b,) and supply equalsdemand.2. Relative prices under the two models. It is now possible to specify con-ditions sufficient to guarantee that black tenants are better off under a housingcode than under a variable supply model provided that no abandonmentoccurs. To do this it is only necessary to determine conditions sufficient forpzR(bz) < plB(b2) (as shown in Fig. 3), since when this inequality holds,equilibrium can only be established with a housing code at piB(k) < pP(k).

If only two assumptions are made, the desired outcome can be established.First, assume that pBu < pkB in a city without prejudice. Second, assume that,when prejudice is introduced, the bid-rent functions of whites are separablein the sense that they can be divided into a portion that depends on k - b anda portion that depends on k, p(k). The sufficiency of these conditions can beshown by writingpzR(bz) : plB(bz),

aspgR(bz) - plR(bl) $ pP(bz) - ,oP(bl). (16)Since k - b is unchanged between bl and bS, we can write (16) aspl(bz) - pl(bl) : pP(bz) - pP(bl). (17)

Since by hypothesis whites have higher incomes than blacks and have flatterbid-rent functions in the absence of prejudice, this implies,pl(bz) - pl(bl) < pP(bz) - plB(bl),

and thus,pzR(bz) < plB@d. (18)

The importance of this proof depends upon the plausibility of our twoconditions, especially the separability assumption. In fact pure separa-bility does not obtain, although conditions can be defined in which it isapproached. From (7), the rate of change of white prices depends on a term-Tkw/q(k), that equals pkW in the absence of prejudice plus a second term(l/q(k))(U&U,) that depends on k - b but is not independent of k.The impact of changes in k on this second term, however, is smaller the lowerI5We assume hroughout that given k and p(k), white households demand for q isindependent of the location of the black-white border although their overall satisfactionlevel is lower the smaller is k-b. Furthermore, we assume that the impact o f a housing codeon new construction is not substantial enough to revise the result in the text.

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

17/19

RACISM AND URBAN STRUCTURE 101

b, h b. kFIGURE 4.

the elasticity of white housing demand and the smaller white householdsincome elasticity of demand for x. Of course, even when separability is notapproximated, it is possible for (18) to hold. Ceterisparibus, thus occurs whenthe difference in the slopes of the black and white bid-rent functions in theabsence of prejudice is relatively large.The condition of the white tenancy must now also be considered. While ina housing market without prejudice, both races gain from code enforcement,once prejudice is introduced this result does not necessarily follow. Twoequilibrium cases are possible and are illustrated in Fig. 4 as 1 and II.16 Whilewhites benefit relative to a variable supply model in Case I, since prices arelower and ba < bl, they do not necessarily gain in Case II for, although heretoo whites gain from reduced prices, this may be cancelled by the fact thatthe black ghetto is closer. (If whites are, in fact, worse off under Case IIthan with a variable supply model, ~~fi(k) must intersect plR(k) at somedistant k). I73. Abandonment. If owners of old housing can choose either to provide &or to abandon their property, then, as has been shown for the nonracist city,the equilibrium price lines under a fixed supply model could be above orbelow pP(k), plR(k). Blacks are therefore less likely to find a housing codesuperior to a free market in which landlords can vary M.

I6 If ~@(6~)>~i~(b~), then a third case is possible in which equilibrium is established fora pB(k) greater than plB(/r). In this situation blacks would be worse off and whites betteroff under a fixed supply model than under a variable supply formulation.I7 Under Case I density in the ghetto will be higher with a housing code model whileunder Case II it will be lower. In both cases maintenance levels are necessarily higher atevery k although in Case I black families who would have lived in relatively new housingbetween ba and bi are now accommodated in older housing at k _< bl.

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

18/19

102 SUSAN ROSE-ACKERMANVII. CONCLUSIONS

The limitations of the model developed here should be emphasized. Thepaper deals only with equilibrium conditions and therefore does not contra-dict the empirical evidence indicating higher housing prices for blacks incities where disequilibrium conditions obtain as a result of a rapid black in-migration. Moreover, the model requires several assumptions which do notnecessarily hold in fact. First, the ghetto is assumed o be capable of expan-sion. It is not surrounded by nonresidential properties or by suburbs practic-ing exclusionary zoning. Second, suppliers are always willing to rent to thehighest bidder and are incapable of collusive activity. Finally, the fact thatmany jobs are located in the suburbs far from concentrations of old housinghas been ignored.Proceeding from this simplified model, the paper has developed Muthstheory of racist behavior by showing that the impact of prejudice on price,quality and density dependsupon the nature of supplier response.The magni-tude of black price gains from racism are smaller the higher the price elasticityof maintenance spending for older housing in ghetto and border regions, thehigher the costs of demolition and new construction and the larger the ex-ternalities from abandoned or poorly maintained housing units. Nevertheless,there does remain a basic asymmetry between the impact of prejudice in ourhypothetical urban housing market and discrimination in other areas, notablythe job market. While blacks benefit somewhat from white racism in housing,they most certainly lose in the job market. Thus, the net impact of prejudiceupon blacks in the city hypothesized by Richard Muth may be either positiveor negative.

REFERENCES1. W. Alonso, Location and Land Use, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

(1964).2. M. Bailey, Note on the economics of residential zoning and urban renewal, Larzd Econ.35, 288-W (1959).

3. B. Cohen, Another theory of residential segregation, Land Econ. 47, 314-315 (1971).4. M. Edel, Planning, market or welfare?-Recent land use conflict in American cities,in Readings in Urban Economics (Edel and Rothenberg, Eds.), Macmillan,New York (1972).5. R. A. Haugen and A. J. Heins, A market separation theory of rent differentials inmetropolitan areas, Quart. J. Econ. 83, 660-673 (1969).6. G. F. Ingram, J. F. Kain, and J. R. Ginn, with contributions by H. J. Brown, andS. P. Dresch, The Detroit Prototype of the N.B.E.R. Urban Simulation Model,National Bureau of Economic Research, New York (1972).7. J. F. Kain, Effect of housing market segregation on urban development, Savings andresidential&awing: 1969 confhence proceedings, U. S. Savings and Loan League.8. J. F. Kain, The journey-to-work as a determinant of residential location, Papers of theRegionaI Science Association 9, 137-160 (1972), Reprinted in Urban Analysis,(Page and Seyfried, Eds.) Scott, Foresman. New York (1970).

-

7/30/2019 Racism and Urban Structure Rose-Ackerman 1975

19/19

RACISM AND URBAN STRUCTURE 1039. A. T. King and P. Mieszkowski, Racial discrimination, segregation, and the price ofhousing, J. Polit. Econ. 81, 590-606 (1973).10. V. Lapham, Do Blacks Pay More for Housing ?, J. Polit. Econ. 79, 1244-1257 (1971).

11. E. S. Mills, An aggregative model of resource allocation in a metropolitan area,American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 57, 197-210 (1967).12. R. Muth, Cities and Housing, University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1969).13. R. Muth, The Demand for Non-Farm Housing, in The Demand for Durable Goods(Harberger, Ed,), University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1960).14. M. Reid, Housing and Income, University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1962).15. T. Schelling, Models of Segregation, Memorandum RM-6014-RC, The RANDCorporation (1969).16. T. Schelling, Neighborhood Tipping, in Racial Discrimination in Economic Life,(Pascal, Ed.) D. C. Heath, Lexington, MA (1972).17. E. Smolensky, S. Becker, and H. Molotch, The prisoners dilemma and ghetto expan-sion, Lund Econ. 44, 420 (1968).