Paul Gauguin (First Impressions).pdf

-

Upload

gelgameh161 -

Category

Documents

-

view

46 -

download

8

Transcript of Paul Gauguin (First Impressions).pdf

-

was an

in France, he worked as a sailor in hi

traveling around the world, then settled

in Paris to pursue a dull career in bus in

first an amateur artist, he took up painting

seriously after losing his job. Unable to sup-

port his family, he still continued to paint,

working furiously to improve his technique,

to sell his work, and to give new meaning both

to the subjects and the styles of painting. In

search of themes and light and color, he trav-

eled to Copenhagen, to the French province

of Brittany, to the Caribbean island of

Martinique, to the southern French town of

Aries (where he worked with the unstable

genius Vincent van Gogh), and eventually he

abandoned his family to pursue his dream of

painting in the bright, natural world of Tahiti

in the South Pacific. There, among lush land-

scapes and beautiful people he painted some

of the most memorable images in the history

of art. Though life was by no means a par-

adise for him (he struggled with poverty and

illness for the rest of his life) Gauguin forged

a style of painting that was wholly original

and created a body of work that will last for-

ever. This is the world of art, where anything

is possible.

WCD OO C/>C/> Oo D3

9 "D

s ccr> oo p*K)

cr

o Q>

54 illu including 34,platt

-

26 i

rr\

-

tti^B

FIRST IMPRESSI

PaulGa

*i

HOWARD GREENFELD

Harry N. Abrams, Inc.. Publishers

7

-

f

-

Series Editor: Robert Morton

Editor: Ellen Rosefsky

Designer: Joan Lockhart

Photo Research: Colin Scott

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Greenfeld, Howard.

Paul Gauguin / Howard Greenfeld.

p. cm. (First Impressions)Summary: Examines the life and work of the nineteenth-century post-Impressionist

painter known for his use of bright colors and his depiction ofSouth Seas scenes.

ISBN 0-8109-3376-41. Gauguin, Paul, 1848-1903Criticism and inter-pretationJuvenile literature. [1. Gauguin, Paul,1848-1903. 2. Artists.] I. Title. II. Series.

ND553.G27G75 1993

759.4dc20

[B] 93-9454

CIP

ACText copyright 1993Howard GreenfeldIllustrations copyright 1993Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ^BPublished in 1993 by Harry N.

Abrams, Incorporated, New YorkA Times Mirror CompanyAll rights reserved. No part of thecontents of this book may bereproduced without the written

permission of the publisher

Printed and bound in Hong Kong

-

Chapter One

The Early 'Years 6

Chapter Two

A Momentous Decision 15Chapter Three

Early Struggles 22

Chapter Four

The Decisive 'Years 32

Chapter Five

To Tahiti and Back

Chapter Six

Exile 77

List of Illustrations 90

Index 92

50

-

Chapter One

The Early ^Kears

Paul Gauguin was a successful stockbroker in Paris, who, at the ageof thirty-five, made a dramatic decision to give up everythinghissecure future, comfortable home, and loving familyin order topursue a difficult career as a painter. He ended his life, twenty

years later, living as an outsider in lonely exile among the primitive societies

of the South seas.

His story is as exciting as it is colorful, but the truth is a little less exot-

ic and dramatic. Gauguin was, without doubt, a courageous man, who

relentlessly pursued his dream. Many considered him, primarily, a bold and

daring genius who refused to compromise, a sensitive artist with a deep

hatred of hypocrisy. For others, he was vain and arrogant, stubborn, some-

times violent, and totally insensitive to the needs of his family and friends.

In fact, he was all of these things, at different times. He was neither

loveable nor likeable, but there is no reason why a great artist must be love-

able or likeable. Nonetheless, his life waseven when the truth has beenseparated from the legenda marvelous one. Not a child genius likeLeonardo or Michelangelo or Picasso who showed extraordinary artistic

ability when very young, Gauguin developed new and profound interests

even when mature, and proved that it was possible, at any time, to change

one's career and goals and way of life. In the case of Gauguin, this change

resulted in the development of an innovative creative artist who gave every-

thing to his art and whose paintings and ideas have had a significant influ-

Self-Portrait for Carriere. 1888/89

This self-portrait of the artist shows him wearing the Breton vest

in which he was often photographed.

-

ence on the course of modern art.

Paul Gauguin's eccentricities, his passion for the exotic, and his stub-

bornness can be traced to his ancestors. Flora Tristan, his maternal grand-

mother, was an extraordinary woman. Born in 1 803 of a French mother and

a Peruvian father, she was a beautiful, passionate, and outspoken rebel who

devoted her entire life to fighting for revolutionary causes. Her personal

life, however, was tragic. Her marriage, at the age of seventeen, to a gifted

painter-lithographer, Andre Chazal, was a failure. When Flora Tristan died,

in 1844, she left her nineteen-year-old daughter, Aline, alone. Soon after her

mother's death, Aline married Clovis Gauguin. Eleven years older than his

bride, Clovis came from a comfortable family of shopkeepers in Orleans, a

city in the heart of France. He had come to Paris in his early twenties to

work as a political writer for Le National.

On April 29, 1847, their first child, Marie, was born. On June 7, 1848,

Aline gave birth to their second child, a son. Christened Eugene Henri Paul

Gauguin, he was to be simply known as Paul Gauguin. His birth took place

during a time of ugly violence and bitter street fighting.

For Clovis Gauguin this turmoil had a personal meaning. Foreseeing a

return to the monarchy he and his newspaper had vigorously opposed, he

decided it would be best to emigrate to Lima, Peru, where he might be able

to start a newspaper of his own with, he hoped, the help of his wife's influ-

ential and wealthy great-uncle.

The family left France for Peru on August 8, 1849. Their voyage ended

in tragedy even before they reached their destination. On October 30, Clovis

died of a ruptured blood vessel. Instead of arriving in Lima filled with

expectations of a bright future, Aline arrived as a poor widow, alone in a

strange land with two small children.

Aline need not have feared. Her mother's family welcomed her with

warmth and generosity. During her five years in Peru, Aline was treated like

the spoiled child of a large, wealthy family. She flourished and radiated a

new-found charm and self-confidence. In fact, it was not as a drab, sweet

housewife that Paul later remembered his mother in a portrait, but as a

noble and graceful Spanish lady, dressed colorfully in the native costume of

Peru; not merely gentle and pure, but quick tempered and fiery.

-

As for Paul, the years in Lima were remembered as an exotic fairy tale.

They were a source of perpetual enchantment. His life in semitropical Peru,

where it rarely rained but earthquakes were common, had a lasting effect

on him as did his association with a wide variety of people he would never

have known in FranceChinese, Indians, and blacks were a part of his dailylife. He never forgot the sight of a young Chinese servant ironing his fami-

ly's clothing, the grocery store where he would sit between two barrels of

molasses sucking on sugar cane, and the playful monkeys, Peru's most com-

mon domestic animals. All of this left an indelible impression on the boy.

In 1855, however, this splendid period came to an end when Aline and

her children returned to France at the request of her father-in-law, who was

dying. Matters of his estate and the family's inheritance had to be settled.

Even more important, as much as Aline enjoyed her sheltered life of luxury

in Peru, she missed France and knew it was time for her children to begin

school in their native country. Paul, seven years old at the time, didn't even

know his native language and spoke only Spanish.

The return to France, to Orleans, where the family first lived in order

to be near Paul's father's family, was difficult for the young boy. Life in the

gray, gloomy city of Orleans was far different from the life he had led in

the warm, lush tropics. In Lima he had been free to do as he pleased, while

in Orleans he had to submit to discipline and attend school with the chil-

dren of ordinary shopkeepers, boys and girls who shared neither his past

experiences nor his dreams of an exotic future.

After a few years, unable to make a decent living in Orleans, Gauguin's

mother moved to Paris, where she set up shop as a dressmaker. She had to

leave Paul behind in a church-supported boarding school until she could

take proper care of him in her new home.

Paul's schooling, in Orleans and in Paris, apparently made little impres-

sion on him. For the most part, he was a poor student, not because he

lacked intelligence but because he was an arrogant youngster. He was so

certain that he was better than all the other students that he never bothered

to study. Socially, he was a failure, too. He was unable to make friends, since

he did little to hide his opinion that most of his classmates were fools.

At the age of seventeen, Gauguin's formal education came to an end.

-

Though his grades had been poor, he had become an avid reader and a keen

observer of the world around him. Arrogance, not ignorance, was his prob-

lem. At a time when young men his age were in school, finding jobs, and set-

tling down, he had only one dream: to become a sailor. As a sailor he could

perhaps rediscover the enchanted world in which he had been raised.

To begin, he enlisted as an officer's candidate in the merchant marine

and, in December 1865, was assigned to a cargo ship bound from the port of

Le Havre, France, to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. This was the first of several voy-

ages he took over the next few years; voyages, as he had hoped, to give him

a chance to explore the world. Not surprisingly, he was most excited by the

charms of the tropics, which had been such a great part of his childhood.

Soon young Gauguin learned that his childhood had come to an end.

During a stopover in India, he received word that his mother, his only solid

link to his early years, had died in St. Cloud, near Paris, on July 7, 1867. She

was only forty years old. It was a tragedy that affected him deeply. In her

will, he learned later, Aline indicated that she knew her son well, suggesting

in her testament that he "get on his career, since he has made himself so dis-

Photos of Paul Gauguin (left)

and Mette Sophie Gad (right)

were taken in 1873, the year

of their marriage. At that

time, they seemed to be

ideally suited to one another.

10

-

liked by all my friends that he will one day find himself alone." Gauguin,

however, was not yet ready to get on with a serious career; there was more

of the world to be seen. In January' 1868, he left the merchant marine and

enlisted in the navy. Two months later, he was assigned to service aboard the

Jerome-Napoleon , a 450-horsepower corvette.

For more than three years, the Jerome-Napoleon cruised the Mediter-

ranean, the Black Sea, and the North Sea, making stops at London, Naples,

Corfu, the Dalmatian coast, Trieste, Venice, Bergen, and Copenhagen.

Gauguin grew tired of his life in the navy; he hated its discipline and the

roughness of his shipmates. In April 1871, he was discharged.

Though those final years at sea must have been unhappy ones, it was

during that period Gauguin grew up physically and emotionally. Still as

short as he had been throughout his childhood (he was barely five feet, four

inches tall when he joined the navy), he had become a powerfully built,

broad-shouldered young man who could, and often had to, hold his own in

a fight. His life as a sailor had taught him to take care of himself and be

more independent. In some ways, however, he had yet to mature. He was

11

-

still unable to decide how to make use of his abilities, and still unable, at the

age of twenty-three, to choose a career.

With this in mind, Gauguin traveled to St. Cloud immediately following

his discharge. There he was astonished to learn that his mother's house had

been burned down by the Prussians, then at war with the French, in 1870.

With that fire, the young man had lost not only a home but also part of a

legacypaintings and valuable objects that his mother had collected inPeru. But his mother had left him a far more important legacy, a wise and

cultured guardian, whose influence on Paul Gauguin would be invaluable.

That guardian, Gustave Arosa, was a wealthy businessman as well as a

talented photographer and a patron of the arts. His large collection includ-

ed several works by some of the finest painters of his timeDelacroix (whowas a close friend of his), Corot, Courbet, Daumier, and several artists who

would later become known as the Impressionists.

Arosa took the responsibility as Gauguin's guardian most seriously. As a

first step, he found him a position in Paris working for a stockbroker, Paul

Bertin. The job, acting as a middleman between stockbrokers and their

clients, was a good one, and Gauguin, though he had had no experience or

training in the field, soon became proficient at it. But he wasn't deeply sat-

isfied by it. Nonetheless, he had in a surprisingly short time found a career

that he could pursue. It was time to put other aspects of his life in order.

Life outside of his job was quiet. He was by nature a rather solitary man

who, when the day's work was done, would usually return to his modest

apartment where he would spend his evenings reading his favorite authors,

Edgar Allan Poe and the French writers Charles Baudelaire and Honore de

Balzac. On Saturdays, however, he would go out, most often to a dance hall.

He liked to dance, and he very much enjoyed the company of women.

It was a calm and pleasant life, far different from the life he had led dur-

ing his years as a sailor. Yet it was in many ways a lonely life for Gauguin,

who felt superior to his colleagues at the office as he had to his schoolmates

and made few friends. Among these few, however, was a fellow employee,

Emile Schuffenecker, who would play an important role in his life. Schuff,

as he was known, was a good-natured man, three-and-a-half years younger

than Gauguin. Schuff was merely a poorly paid clerk, whose future did not

12

-

seem nearly so bright as Gauguin's did. What drew the two men together

had nothing to do with their jobs; it was their common enthusiasm fordrawing and painting, which for Schuff was already a serious hobby and

had started to interest Gauguin through his friendship with Arosa.

Gauguin's position in the firm was an enviable one; his increasing

enthusiasm for art proved to be a stimulating distraction, and his friendship

with Schuff provided him with the male companionship he needed. Now hewas ready to take on the responsibilities of a wife, a home, and a family.

In the autumn of 1872, Gauguin met a woman with whom to share hislife. Her name was Mette Sophie Gad. Born on a small Danish island, Mette

and her siblings were brought up in Copenhagen by their widowed mother.

Even at an early age, Mette had shown signs of the independence and

strength that would characterize her behavior all of her life. At the age

of seventeen, she left home to take a position as governess to the children of

the prime minister of Denmark. This enabled her to come into contact with

a social and intellectual world she had never known in her conventional

middle-class home. Through the people she met, her outlook broadened and

her knowledge of the world beyond Denmark grew, so much so that, by the

time she was twenty-two years old, she was ready to accept an offer by the

wealthy father of one of her friends, Marie Heegaard, to join his daughter

as a companion and guide on an extended visit to Paris.

It was during this visit to the French capital that Gauguin met the two

Danish women. Though he was impressed by both of them, he was especial-

ly attracted to the vital young Mette who was so unlike the superficial French

women he had known. Mette's keen intelligence and forthrightness set her

apart from the others, as did her lack of pretensions.

In a very short time, their friendship grew. At first, Gauguin would meet

both women for lunch, but soon he and Mette began to meet alone. Their

talks became increasingly personal and intimate, and in January 1873, only

a few months after their first meetings, they made plans to marry.

The wedding took place on November 22, 1873; the bride was twenty-

three years old, and the groom twenty-five. They had the whole world before

them, and they delighted at the prospect. As they set up their house in a

comfortable apartment in Paris, their future seemed secure.

13

-

^

/

>*

M

-

Chapter Two

A Momentous Decision

Forthe first few years, their marriage seemed an ideal one. In spite

of the stock market crash in 1873 and a long period of unsettled

economic conditions in France and much of Europe, the young

stockbroker continued to prosper. Gauguin's investments had been

sound ones, and he was able to provide more than adequately for his fami-

ly. His family grew in number. Emile, a son, was born in 1874; a daughter,

Aline, was born in 1877; a second son, Clovis, was born in 1879. It was, on

the surface at least, the perfect householda loving husband and wife,happy, healthy children, and, for the head of the family, the anticipation of

a brilliant business career.

Nonetheless, during these first apparently tranquil years, a significant

change was taking place, one that Mette failed to recognize at the time, but

would deeply affect their lives. Even before the birth of their first child,

Gauguin's interest in art was developing into a passion and was gradually

beginning to dominate his thoughts.

His friendship with Schuff was partially responsible for this. At first, the

two men merely talked about art, but soon Gauguin's colleague encouraged

him to try a hand at painting. In the beginning, Gauguin was content to

enjoy this as a hobby. Often on Sundays, usually in the company of Schuff,

he would take his paint box and easel to the countryside outside Paris, and,

on occasional evenings, he would join his friend at a nearby school for

artists, the Academie Colarossi, where they would sketch and paint from

models. Gradually, however, encouraged by those who had seen his work

and had liked it, he began to take his own art more seriously and to devote

more time to it. By 1876, he felt so sure of himself that he sent one of his

landscape paintings to the Salon, the annual government-sponsored exhibi-

tion, where it was accepted by the jury and hung alongside the works of

15

-

experienced professional painters. The mere acceptance by this jury was a

surprise, since the Salon was by far the most important of all Parisian exhi-

bitions. Even more astounding was the fact that Gauguin's painting was

actually singled out by one critic as showing promise. The stockbroker who

had never formally studied art had every reason to be proud of himself. Yet,

for some reason, he told neither his wife nor his close friend Schuff of this

success.

Gauguin's passion for painting increased, and an even more profound

influence than Schuff was that of Gauguin's guardian, Gustave Arosa. Art

was a topic for lively discussion and debate at Arosa's homesin Paris andin St. Cloudwhich Gauguin visited frequently. The paintings that hung onthe walls of these homes stimulated him to visit museums and private art

The Impressionist painter Camille Pissatro was one of Gauguin's early

mentors, who gave the younger artist his time and his knowledge generously.

Pissano added his sketch of Gauguin (left) to one ofhimself that

Gauguin had presented to his mentor.

X

16

-

I ,_. SJJl^ntS

The Schuffenecker Family. 1889

Gauguin was staying at the home of the Schuffeneckers when he painted this

iniflattering portrait of the family. Louise Schuffenecker, whom Gauguin had

described as a "pest, " looks bitter and sad, while there is something pathetic and

servile about Schuff gazing at his wife.

galleries, where he sharpened his eye and developed a critical understand-

ing of the forms and techniques of painting. He learned from and liked

much of what he saw, but he was especially drawn to the paintings of a

small band of courageous artistsClaude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir,Alfred Sisley, and Camille Pissarrowho were to become known as theImpressionists.

The Impressionists had found a new method of artistic expression,

de\ eloping what at that time was considered a startling new technique.

17

-

They used small brush strokes, dabs of rich pure color, to capture on canvas

not a static scene but a fleeting impression. They worked in direct contact

with nature, unlike other painters who, even if they began work outside,

completed their canvases in their studios.

The results of their daring experiments were brilliant, yet their struggle

to have their works shown to the public was a long and difficult one. The

jury of the official Salonthe same one that accepted Gauguin's competentbut unexceptional landscaperejected the Impressionists' paintings as toorevolutionary, and very few private galleries were willing to show them.

Gauguin, at the beginning of his development as a painter, was far from

indifferent to these paintings. On the contrary, he was as excited by what he

saw in the galleries, as he was by those in Arosa's home. He began to buy

them, and by 1880 he had a collection of outstanding Impressionist works.

Furthermore, he had a chance, through Arosa, to meet many of the artists,

among them the man who would become his first mentor, Camille Pissarro.

Pissarro's background was as exotic as his own. Born in 1831 on the

island of St. Thomas in the West Indies, he was

the son of a Creole mother and a Portuguese-

Jewish father. At the age of twelve, his parents

sent him to Paris to be educated. It was there

that he first developed an interest in art,

and, in 1847, when he returned home to

work in his father's general store, he

spent more and more of his time

sketching local scenes. His family

was strongly opposed to his idea of

becoming a professional painter, but

the young man defied them. In

1852 he ran off to Venezuela to

escape the dreary prospect of a

future as a shopkeeper. A few

years later, his family gave in to

his wishes, giving him permis-

sion to return to Paris, where he

-

could best pursue his career as an artist. There, after his work was rejected

repeatedly by official circles, he joined forces with those painters who

would lead the Impressionist revolution.

It was Pissarro who guided Gauguin as he developed from a very gifted

amateur painter into a serious professional artist. During the summers of

1879, 1880, and 1881, the two men often painted together at Pontoise, a

small village near Paris, where Pissarro and his family had lived since 1866.

During these years, Pissarro taught Gauguin to change the colors of his

palette, to concentrate on the three primary colorsred, blue, and yellow

and their complementariesgreen, orange, and violet.In addition to serving as Gauguin's teacher, Pissarro introduced the

younger man to his circle of friends, among them the Impressionists. These

men took Gauguin seriously as an artist, and soon he was invited to show

his work at the exhibitions that they organized annually as a protest to the

official Salon which had shunned them. In 1879, Gauguin entered a marble

portrait head of his son Emile at the fourth

Impressionist Exhibition. (He had learned

the art of sculpture from a neighbor, a

marble cutter.) The following year he

showed another marble bust, this time of

Mette, as well as several canvasesland-scapes and scenes of Pontoise, which he

had painted the previous summer with

Pissarro. Gauguin's work was noted by crit-

ics of this last exhibition, as was his stylis-

tic indebtedness to Pissarro.

Gauguin's participation in the sixth

Impressionist Exhibition, which took

place in April 1881, marked a turning

point in his career. For the first

time, he was praised by an in-

fluential critic, J. K. Huysmans, Jm

a novelist and poet who was

among the first critics to

t

-

Snow Scene. 1883

Gauguin painted this large and ambitious painting while he was influenced by

the Impressionists. It is believed to show the garden ofa home Gauguin rented

in Paris from 1880 to 1883.

20

-

appreciate the paintings of the Impressionists. Huysmans singled out a

nude study which he felt revealed in Gauguin "a modern painter's tempera-

ment." He added: "among contemporary painters who have treated the

nude, none has yet given so passionate an expression of reality."

Understandably, these words from a powerful critic were of great

encouragement to Gauguin. Yet his doubts only increased the following

year, when thirteen of his works shown at the seventh Impressionist

Exhibition were coldly received, even by Huysmans.

Clearly, it was time to choose between his painting and his business

career. This choice was made easier by an event beyond Gauguin's control.

In January 1882, the stock market collapsed. Investors, large and small, lost

their money, companies were forced into bankruptcy, and stockbrokers

were fired. As a result, his job was in jeopardy. This seemed the right time

to make a move. He decided to give up his job in business and devote all of

his energy to painting, no matter what the consequences.

The news that her husband had left his job came as a shock to Mette. Of

course, she had been aware of his increasing passion for art, but she had

failed to recognize the depths of that passion. After all, he had a family to

support, and to do that he would have to find another job so that they could

continue to live in the comfortable manner to which she was accustomed.

Gauguin also worried. Another child was expected later that year, and

he had to make a living. He turned to Pissarro for help. "I find myself now

in inextricable difficulties," he wrote him. "I have a large family and a wife

who is incapable of enduring misery. Thus I cannot devote myself entirely

to painting without being assured of at least having half of the indispens-

able. ... it is absolutely necessary that I find my livelihood with painting."

Pissarro was sympathetic, but he could offer no help. He had known

what it was to struggle as an artist for many years, for he too had a large

family he was barely able to support. But he worried that Gauguin was too

concerned with making a living and too afraid of that struggle.

In this, Pissarro underestimated the determination of his friend. Gau-

guin had made up his mind: in his own eyes, he was already a painter. On

the birth certificate of his fifth child, Pola, a son born on December 6, 1 883,

he listed his occupation as "artist-painter." There would be no turning back.

21

-

Gauguin's decision to devote his life to his art, whether it wascourageous or irresponsible, brought about an enormous

change in the everyday life of his family. Their savings had

been depleted in the stock market crash, and their income was

practically nonexistent. Mette was especially distressed; instead of being the

wife of an affluent businessman, she would now have to adjust to being the

wife of a struggling artist.

The first change in their way of life involved moving out of their elegant

Parisian home, which they could obviously no longer afford. Instead of find-

ing more modest quarters in the capital, Gauguin decided, in early 1884, to

move his family to an apartment in the port city of Rouen in northern

France, where living would cost less than it did in Paris. Pissarro had lived

and painted there the previous year, apparently with considerable success,

and Gauguin felt that his art, too, might flourish away from Paris. He want-

ed to develop his own style and not imitate the Impressionists. Besides, he

was certain that he could sell his paintings to the citizens of Rouen and

receive lucrative portrait commissions from them.

Rouen, however, proved to be a disappointment. Living there was not as

inexpensive as Gauguin had expected, and the few residents who bought

paintings showed little or no interest in his portraits or his landscapes. As

an artist, in Rouen as in Paris, Gauguin found it extremely difficult to fur-

nish his family with even the bare necessities. Mette suffered, too. Her hus-

band, whose principles and goals now seemed so different from her own,

was becoming a stranger to her.

The situation worsened steadily. By July, little more than six months

after their arrival, they had become so desperate that Gauguin was forced

to sell his insurance policy for half its value. And by early autumn, Mette

22

-

was able to convince him that only a move to Copenhagen, her former

home, could save their marriage and enable them to find happiness again.

In October 1884, Mette set off for Denmark with their five children. A

month later, Gauguin joined them, bringing his art collection with him.

Before leaving France, in order to insure some income, he had found work

as the Danish representative for a manufacturer of waterproof canvas.

Life in Copenhagen was even worse than it had been in Rouen for

Gauguin. Upon his arrival, he had been optimistic, trying his best to learn

the new language and to sell enough canvas to support Mette and their chil-

dren. But, in spite of his

~

^

good intentions, Mette's

Gauguin spent three months in Pont-Aven, family made life unbearable

Brittany, beginning in July 1886. There he found for him. They showed noth-

colorful, picturesque subjects, such as these ing but contempt for this

women washing their clothes in the Aven, which so-called artist, who was

inspired some of his finest early paintings. un-able to make a living at

his painting or at anything

else. Soon Mette was forced

to give French lessons and

translate French novels in-

to Danish for money.

Worst of all, Gauguin

was unable to spend time

painting. "I am more tor-

mented by art here than

ever," he wrote to his

friend Schuffenecker in

Paris, "my money difficul-

ties as well as my search-

ing for business cannot turn me from it. . . . I'm broke, fed

up to the back teeth, that's why I console myself dreaming."

In May 1885, Gauguin complained in a letter to Pissarro that he was at

the end of his courage and resources. "Every day I ask myself whether it

wouldn't be better to go to the attic and put a rope around my neck," he

24

-

wrote. "What prevents me from doing so is painting, yet here precisely Liesthe stumbling block. My wife, the family, everybody reproaches me for thatconfounded art, pretending that it is a disgrace not to earn one's living. But

the faculties of a man cannot suffice for two things, and I can only do onething: Paint. Everything else renders me stupid. . . ."

In June 1885, Gauguin

returned to Paris accompa-

nied by his six-year-old son

Clovis. He was penniless

and he had little hope of

making a living. For one

year he was completely

dependent on the few

friends who occasionally

offered him hospitality

and lent him money. In

spite of his qualifications,

he was unable to get any

kind of job at the stock

exchange. A position as

assistant to a sculptor fell

through when the sculp-

tor's commission was

canceled. And all of his _^__^_^^_^__^_

efforts to sell his own

paintings had failed; Paul Durand-Ruel, the courageous dealer who had

helped the Impressionists in their early struggles and the only dealer he felt

might take an interest in his work, was himself near financial ruin.

As a result, Gauguin was not able to provide a home or even enough

food for his young son. The two moved wearily from one rented room to

another, carrying with them a trunk they had brought from Denmark. At

times, Gauguin found friends who would take Clovis in for a week or two,

but often the young boy slept on a rented bed, while his lather, wrapped in

a rug, slept on a mattress on the floor. At one point, all (hat Gauguin and his

Guests and staff in front ofthe Gloanec

Inn in Pont-Aven. Gauguin is seated in the

front row, second from left.

25

-

son had to eat was breadand the bread had been bought on credit.In December, near tragedy struck when Clovis took ill with smallpox, a

potentially fatal disease. Fortunately a generous neighbor looked after the

boy, while Gauguin, desperate, found work hanging posters in a railroad

station at a meager salary of five francs a day. Promotions followed

Gauguin was appointed inspector and then administrative secretaryandthese eased their financial situation. This was only a temporary solution to

his problem, however. Gauguin's mind was still first and foremost on his art.

Since his return to Paris, Gauguin had had little chance to paint and no

opportunity to show his work. For this reason, he was preoccupied during

the first months of 1886 with the first such opportunitythe forthcomingeighth Impressionist Exhibition. Perhaps the paintings he showed there

would gain him the recognition and sales he so badly needed.

That exhibition, however, was in many ways a failure. The Impression-

ist movement was falling apart. Its members quarreled, and three of them

Renoir, Monet, and Sisleyeven refused to take part in what was to be thelast group exhibition. All attention that year was focused on the work of a

new school of painters who had developed a technique known as Pointillism

the use of little specks of pure color which, when seen at a distance, blend

in the eyes of the viewer. Because of the excitement, both favorable and un-

favorable, generated by the masterpieces of this new movement, Gauguin's

nineteen paintings and one wood-relief were ignored by most viewers.

When the eighth Impressionist Exhibition came to an end in June 1886,

a year had passed since Gauguin had left his wife and four of their children

in Copenhagen. During that year, the couple had corresponded only spo-

radically. Mette's letters revealed her anger and bitterness. Their marriage

might possibly work, she felt, but only if he would give up the idea of mak-

ing a living as an artist and return to the world of business. Though he, too,

hoped for a reconciliation, Gauguin's letters were equally bitter. He accused

his wife of living in luxury while he struggled to make ends meet. He felt

that it was he who had been abandoned, that Mette had coldly rejected the

man he really wasan artist.During that year, despite the setbacks and humiliations, Gauguin never

wavered from his devotion to his art. He never doubted that he would some-

26

-

day receive the recognition he deserved. His failure, he felt, could be blamed

largely on the never ending struggle to overcome the economic and physical

deprivations that consumed so much of his strength and energy. If only he

could find the time to devote himself completely to his art . . .

Such a period came sooner than he had expected. In July, a generous

loan from a distant relative enabled him, temporarily at least, to set aside

his exhausting struggle to survive. After sending Clovis off to boarding

school, he set out for Brittany, an isolated primitive region in northwest

France. There he settled into the small picturesque village of Pont-Aven,

about twelve miles from the dramatic, rocky coast of the Atlantic Ocean,

where he hoped to remain for a few months.

Pont-Aven had, for some years, attracted to it artists from many parts of

the worldAmerica, Holland, England, and Scandinavia among them. Itsappeal was obvious. A remote community of proud and somber farmers,

millers, and fishermen, their way of life

seemed untouched by modern civilization. A

pious people, they observed their religious

festivals as they had for centuries. The

women continued to wear their native cos-

tumestheir smocks and bonnets and highlace headdresses. And, for a few francs, they

would pose for visiting artists.

Because of these qualities, Pont-Aven

provided the ideal setting for a painter eager

to capture on canvas the character of a

unique town, its citizens, and the gray, mys-

terious countryside that surrounded it. As a

This cylindrical vase, an example of the

collaboration between Gauguin and the ceramist

Ernest Chaplet, is dated 1886-87. The two

figures in the foreground are based on a painting

offour Breton women by the artist.

27

-

28

-

further attraction, living in Pont-Aven

was inexpensive, especially for those

who were fortunate to find a room at the

inn owned by Marie-Hoanne Gloanec,

who not only charged little rent but

never insisted that artists pay their bills

on time.

As soon as he arrived Gauguin took

a room in the attic of the Gloanec Inn.

For the first time in his life, he was free

to live the life of a painter. Aloof and

superior as ever, he made only one

friend, a Frenchman named Charles

Laval, who was fourteen years his

junior. The other painters remained

strangers to him; he kept his distance

from them, usually keeping silent when

in their company at the inn. He pre-

ferred to carve decorations on a walking

stick or on a pair of clogs while the oth-

ers passed their evenings in what he

considered idle conversation.

A solitary figure, wearing a blue

fisherman's jersey with a beret pulled

over one ear, Gauguin became known as

an eccentric, and not a very likable one.

Locusts and Ants, one of ten

lithographic drawings executed by

Gauguin in 1889, offers evidence that

the painter was able to master the use of

a new mediumlithography in aremarkably short time.

29

-

But he was soon respected for the boldness and vitality of his art, which

seemed revolutionary to most of the other painters in the village. Through

them, he gained self-confidence and boasted to Mette, "I am respected asthe best painter in Pont-Aven. . . . Everyone discusses my advice."

In the middle of October, this carefree period of creativity came to an

end. It was time to return to Paris. Gauguin had benefited greatly from liv-

ing among a quiet, simple people, whose culture differed in many ways

from his own. By moving further away from the influence of Pissarro and

the other Impressionists, his work began to develop a style which would,

during his next stay in Pont-Aven, become truly his own.

Back in Paris, Gauguin learned quickly that he still could not make a liv-

ing through his art alone. Faced with the need to support himself and Clovis

who had returned from boarding school, he turned his hand to ceramics.

But his attempts to "communicate to a vase the life of a figure, while retain-

ing the character of the material," as he wrote, were as impossible to sell as

were his paintings. His prospects were no better than they had been before

he went to Brittany. Once again nearly destitute and unable to take care of

his son, he wrote Mette that he had to escape and for the first time had

dreamed of going away to a primitive place in a warm climate, where he

could live inexpensively off the land. It was a dream that would haunt him

for the rest of his life.

At the end of what had been a harsh and trying winter in Paris, he

worked out a plan to make this dream come true. He would go to Panama,

where he had relatives, and move to a small, sparsely inhabited island off

the coast to live the simple life he so desperately needed.

In early April 1887, his wife arrived in Paris to take Clovis back to

Copenhagen. A few days later, Gauguin, accompanied by Charles Laval,

embarked for Panama. After a long, rough journey, the two men arrived at

their destination. They learned quickly that they would have more trouble

reaching "paradise" than they had expected, since Gauguin's relatives

showed no interest in helping them. And they also learned that the island,

where Gauguin hoped they could live like savages, "on fish and fruit for

nothing . . . without anxiety for the day and for the morrow," had already

been spoiled. The natives, anticipating an economic boom because of the

30

-

building of the Panama Canal, had raised the price of land so that it was far

beyond the reach of the two struggling artists.

One hope remained: to travel back to another island, Martinique, which

they had seen on their way to Panama. The two men set out to earn enough

money to pay for the tripLaval by painting portraits, and Gauguin by work-ing twelve-hour days helping to dig the Panama Canal.

A month later, they had earned the price of their passage to Martinique.

Upon arrival, they rented , ...

an abandoned hut a few/^i^P-)~

/^^miles from the village ) M

of Saint Pierre. Soon, NGauguin realized that he

had found the primitive

island he had been looking

for. The landscape, with its

brilliant colors, and the

warm, friendly natives

delighted him. "I can't de-

scribe for you my enthusi-

asm for life in the French

colonies," he wrote Mette.

If only he could find an

outlet in France for his

paintings, he assured his

wife, the whole family

could join him in Martinique where they would live happily together.

There was one serious flaw in what was otherwise an ideal existence.

The island's damp tropical climate proved to be devastating for Gauguin.

Already weakened from his journey from France and his exhausting physi-

cal labor on the Panama Canal, he developed dysentery and malaria. After

four months, he had to return to France for medical treatment, leaving his

hopes of finding a new life on Martinique behind. But all had not been lost.

During his time on the island, he completed twenty luminous paintings in a

style which would soon be recognized unmistakably as his own.

Gauguin sent this sketch ofone of his

most famous paintings, The Vision after the

Sermon, to Vincent van Gogh in a letter

ofSeptember 22, 1888.

31

-

Chapter Four

The Decisive ^fears

Having worked his passage home as a deckhand on a schooner,Gauguin arrived in France in November 1887 without Laval,

who remained in Martinique. Weak and thin, and still suffer-

ing from the effects of the illnesses, he was destitute, forced

to seek refuge in the home of his old friend Schuff until he found his own

small studio.

With very few exceptions, no one seemed interested in his paintings, but

among those enthusiastic about his progress was a Dutch painter, Vincent

van Gogh, whom he had met shortly before leaving for Panama. The twomen were temperamentally very different. Gauguin was cool headed and

reflective, while Van Gogh was more emotional and impulsive. But they had

a great deal in common. Van Gogh, five years younger than Gauguin, had

also taken up painting as a profession at the relatively late age of thirty,

although he had drawn and sketched long before then. He, like Gauguin,

was an artist with strong convictions, and both searched for new ways of

expressing themselves through their art. They were, because of this, united

by a feeling of isolation from the popular artistic movements of their time.

Van Gogh had come to Paris in 1886 to live with his devoted younger

brother, Theo, who worked in an art gallery. Theo, a kind and gentle man,

sold works of many contemporary painters. Sharing his brother's enthusi-

asm for Gauguin, he did his best to sell his paintings through his gallery. A

few did sellTheo himself bought three canvasesbut the money earned

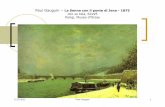

Tropical Vegetation. 1887

This painting with a view of the bay of Saint-Pierre was painted during Gauguin's

stay in Martinique. The volcano, Mount Pele'e, can be seen in the background.

32

-

33

-

was not nearly enough to support Gauguin. The best solution for the debt-

ridden artist was to return to Pont-Aven, where he could live cheaply and

take advantage of the generosity of Madame Gloanec.

Life in Pont-Aven was difficult during the winter of 1888. The climate

was harsh and the town was deserted. Members of the art world only visit-

ed during the spring and summer. Gauguin's health had not yet returned to

normal, and he was sometimes so poor that he couldn't afford canvas and

paints. He also worried about his family in Denmark; he had still not given

up hope of a reconciliation. In March, desperately lonely, he wrote to Mette:

"All alone in the room of an inn from morning till night, I have absolute

silence, nobody with whom I can exchange ideas." Yet he believed that hisart would reach its maturity in Pont-Aven. "I like Brittany, it is savage and

primitive," he wrote to Schuff. "The flat sound of my wooden clogs on the

cobblestones, deep, hollow, and powerful, is the note I seek in my painting."

During this period, he kept in contact with Theo and Vincent van Gogh.

The former continued to try to sell his paintings, but he had little luck.

Vincent wrote to Gauguin of his hopes to form an artists' cooperative to help

promote and sell their work. He suggested, too, that Gauguin come to live

and work with him in Aries, in the south of Fiance, where they would be

joined later by other struggling artists.

At first, Gauguin ignored this suggestion. But in the late spring Theo

came forth with a new and more feasible plan. Having just received a small

unexpected inheritance, the art dealer offered Gauguin a fixed monthly

allowance in exchange for one painting per monthon the condition thathe agree to join Vincent in Aries. The two men could keep one another com-

pany, while sharing expenses. This time Gauguin accepted the offer, agree-

ing to come to Aries as soon as he had settled his debts to Madame Gloanec

and to his doctor.

He was, however, in no hurry to leave Pont-Aven. As the warm weather

returned to Brittany and visiting painters took up temporary residence in

what had become a summer art colony, Pont-Aven again came to life.

Gauguin acquired a following of younger artists who came to look upon him

as their teacher and leader. It was a role he enjoyed, a recognition of his

power and strength as a painter.

34

-

Part of the credit for his growth as an artist during this period must be

given to Emile Bernard, a young Frenchman (he was only twenty years old

at the time) who arrived in Pont-Aven in August. The two found they had a

great deal in common. Bernard was as profoundly interested in literature,

music, and philosophy as he was in art. He and the older painter, whom helooked to as his master, soon became close friends and colleagues, enthusi-

astically working together and discussing their theories of art and their

methods of painting. It became clear that they had, independent of one

another, reached similar conclusions. Their goals were the same: to express

their inner feelings and visions through their painting rather than to depict

Early Flowers in Brittany. U

This light-filled landscape, painted at Pont-Aven in the springtime, was greatly

admired by Degas, who considered purchasing it when it was exhibited in Paris.

35

-

reality or portray nature like the Impressionists. Gauguin wrote Schuff:

"Don't copy nature too literally. Art is abstraction; draw art from nature as

you dream in nature's presence."

To reach these goals, Gauguin and Bernard developed a new style,

which came to be known as Symbolism or Synthetism. Influenced by

Japanese prints, as well as folk art, tapestries, and ancient frescoes, their

paintings rejected traditional perspective and made use of brilliant flat col-

The Vision after the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel). /