Operation Save A Duck -...

Transcript of Operation Save A Duck -...

Stephen J. Lee

Duck. These events spurred some ofthe state’s earliest legislative debateon controlling pollution to protectthe environment.

The winter of 1962–63 was cold.On Friday, December 7, 1962, work-ers at the Richards Oil Companyplant on the Minnesota River inSavage pumped “cutter” oil from railcars into a storage tank through along, 10-inch-diameter steel pipe -line. (Cutter oil is thin, like keroseneor diesel fuel, and used to makeheavy oils pumpable.) When the

workers left for the evening, theyneglected to close the valve betweenthe pipeline and a large abovegroundstorage tank. They also forgot toopen steam lines that kept the oil inthe pipeline warm and flowing.1

During the weekend, when even -ing temperatures dipped below zero,the uninsulated, unheated pipe con-tracted and broke in three places.Some one million gallons of oil, theentire contents of the tank, drainedfrom the broken pipeline over 30acres of ground.2

Catastrophes often trigger

advances in environmental protec-tion. This was true in Minnesota inthe winter of 1962–63, when morethan three million gallons of soybeanoil spilled in Mankato and floweddown the Minnesota River to joinmore than one million gallons ofindustrial oil spilled in Savage. Thegooey mess killed an estimated10,000 ducks near Red Wing andHastings and prompted GovernorKarl Rolvaag to activate the NationalGuard in the futile Operation Save a

105

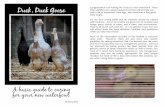

A canvasback duck immobilized by soybean oil near Hastings; thick oil trails inthe Mississippi River near South St. Paul, April 1, 1963.

AND THELEGACY OFMINNESOTA’S1962–63 OIL SPILLS

Operation Save A Duck

Stephen Lee is the emergency responsesupervisor of the Minnesota PollutionControl Agency.

106 Minnesota History

Because the family-ownedRichards plant was unstaffed duringthe weekend, the spill was not dis-covered until Monday morning. Bythen, the oil was draining onto theice of the Minnesota River througha culvert that pierced a dike builtbetween the plant and the river. Theculvert had a one-way flap valve thatprevented river water from floodingthe plant but allowed storm-waterrunoff—or oil—to pass through tothe river. Oil spread downstream ontop of and under the ice.3

By the end of December, therewere numerous sightings of oil ontop of river ice. The downstreampower plant at Black Dog reportedthat oily water was interfering withits turbine condensers. Fresh snow-falls and poor access to the rivermade it difficult to assess the scopeof the oiling, but a stretch of icethree-to-four miles long contained apool of oil. Game wardens and statehealth-department staff tracked theoil back to the Richards property.4

Richards employees and ownersrepeatedly denied any problems atthe plant beyond drips from leakingpumps and routine, minor spillage.For a time, state officials were ex -pelled from the site. It was not untilMarch 18, 1963, that a plant owneradmitted the million-gallon Decem -ber spill. He said that attempts topump up the oil had been made, butonly 2,000–10,000 gallons had beenrecovered. In this time before thefederal Environmental Protection

Agency or a state Pollution ControlAgency, it was the Department ofHealth’s Water Pollution ControlCommission that requestedRichards to halt the continuing oildrainage into the river. This wasdone after some delay, but by lateMarch the ice had gone out and thebulk of the oil had already moveddown the Minnesota River into theMississippi.5

Meanwhile, back in January,another cold spell had settled overthe Minnesota River valley. Over -night lows fell to -25° F. in Mankato,home of Honeymead Products Com -pany, the largest soybean-processingplant in the world. Honeymeadstored its soybean oil, which has theconsistency of cooking oil, at a tem-perature of 50°–70° F. in large,aboveground storage tanks. One ofthese steel tanks had been boughtused in Texas, disassembled, andreconstructed in Mankato. This 40-foot-high, 100-foot-diameter, 3.4million-gallon-capacity tank hadbeen further modified by welding an8-by-8-foot steel panel near its bot-tom for entry and cleaning.6

In severe cold, a phenomenoncalled brittle fracture can cause thesudden collapse of steel tanks. Inaddition, inserting a flat panel in thecurved circumference creates mech -anical strains on the steel and welds.On the cold morning of January 23,Honeymead’s reconstructed storagetank failed, “unzipping” from theupper corner of the square plate tothe top of the tank. A tidal wave of2.5 million gallons of crude soybeanoil washed over nearby tanks andrailroad tracks, flooding severalblocks of southwest Mankato. The

powerful force of escaping oilpushed the hull of the big tank back-ward into five smaller tanks contain-ing another .5 million gallons ofsalad oil. When the piping to thesetanks broke, their contents amplifiedthe spill to about 3 million gallons.7

Cars, homes, and businesses weresurrounded by the pool. Several cityblocks flooded three feet deep in oil.When the tank failed, Herbert Kurth,the boss of one group of employeeseating lunch huddled around a stovein a nearby brick building, went tothe door to investigate the bang thatsounded like rail cars coupling at toogreat a speed. He saw a 40- or 50-foot-tall storage tank riding towardhim on a wave of oil. Running to theback of the building, he kicked out awindow to enable employees toescape. (He was reportedly crankyafterwards, because the employeesdove out the window first, leavinghim behind in two feet of oil.) It was“every man for himself,” recalledemployee Edward Ward.8

Harvey (Choppy) Fortney wasdriv ing a truck through the yardwhen the tank burst. He saw the 30-foot-high wave of yellow oil comingtoward him and thought it was fire.Propelled through the air above theoil was a tank trailer that, along withthe oil, slammed Harvey’s truck intoa pile of beams. The terrified, semi-conscious, and oily Fortney slippedfrom rescuers’ grasps twice while hewas being extricated from his truck.9

Standing in the path of the oilwave were 300 to 400 barrels oflecithin and other products. HaroldHartwell outran the oil but got hit bya flying barrel. David Wilmes hadjust left his post when it was deluged

Summer 2002 107

Aerial view before the spill of Honeymead Products Company, the largest soybean-processing company in the world in 1963.The large tank at lower right ruptured, and its oil gushed into Mankato and the Blue Earth River.

(Above) The crumpled shell of a Honeymead tank with a damaged tank behind it;(below) lecithin drums and one of the railroad cars (at right) tossed by the tidal waveof oil toward the Minnesota River.

108 Minnesota History

by a wave of oil that piled barrelsonto his work station. Co-workersfrantically pulled barrels off the pilelooking for Wilmes’s body until hereported in from the lab. Gerald Erkeland others were in the extractionbuilding when the oil ripped off thedoors and flooded it. Men climbedstairs and ladders to escape thechurning wave, some of which camein through windows and stainedrafters six stories above ground.

Evelyn Herman watched from thewindow of her home near the plantas two loaded railcars, estimated toweigh 80 to 90 tons each, washed offthe tracks, traveled about 300 feet,and plunged into the Blue EarthRiver. One railcar broke though theice, allowing oil to drain directly intothe water. Her house was surroundedby the oil, which quickly cooled to agooey, lardlike consistency. She andher children were ma rooned in thehouse for several days. At the Man -kato sewage-treatment plant, em -ploy ees discharged raw sewage direct-ly into the Min ne sota River to preventoil from gumming the works.10

About half of the 3.5 million gallonsof oil spilled directly into the BlueEarth River. As for the rest, on thefirst day employees used graders andloaders to push oil off roads intoditches, so that it could eventuallyflow into the river. That practice wasquickly halted by request of the De -partment of Health. Over the nextfew weeks Honeymead and city em -ployees continued to scrape, pump,and push the sticky mass of oil anddebris. An estimated 700,000 to800,000 gallons were recovered andpumped into railway tanker cars.Following common practice in the

Summer 2002 109

1960s, a large amount was carted offand dumped in a ravine two mileseast of Rapidan, Minnesota, alongthe Le Sueur River. Some recoveredoil was fed to hogs.11

About a month after the

Honeymead spill, and almost threemonths after the Richards spill, theice went out on the Minnesota River,releasing more oil into the water atboth sites. It moved quickly down-stream into the Mississippi River,where, on March 25, it was seenbetween St. Paul and Newport. In -spectors visiting the plants on March

22 and 28 discovered continuingdis charges of oil. On March 29 ob -servers reported the first oil-covereddead ducks south of St. Paul.12

As serious spill problems becameapparent late in March, Minnesota’sWater Pollution Control Com mis -sion and Department of Conser va -tion and the U.S. Army Corps ofEngineers pressured Richards andHoneymead to stop further pollutionby constructing berms, excavatingdirt, and burning pooled oil. Richardspersonnel and the local fire depart-ment began open burning of oil fromthe ditch on their property.13

As temperatures rose, oil in thedebris Honeymead had dumpedbegan to flow to the Le Sueur River,then to the Blue Earth River, passingthe Honeymead plant where it hadoriginated, and finally to the Minne -sota River. In response, the companydispatched bulldozers to dike theupstream ravine.14

From St. Paul, the Mississippiflows rapidly south then turns east-ward in the Pine Bend area that in -cludes extensive backwaters such asSpring Lake, largely formed by theconstruction of the Hastings lockand dam in the 1930s. Past Hast -

Oil that spilled at Richards Oil Company in December 1962 and Honeymead Products Company in January 1963 flowed downthe Minnesota River and into the Mississippi.

110 Minnesota History

ings, just south of Red Wing, thechannel widens to create Lake Pepin.In late March, unmelted ice at thehead of Lake Pepin dammed up thefloating oil, which backed up to RedWing and Hastings. This coincidedwith the peak of waterfowl migration.15

It was on March 28 that 16-year-old John Serbesku first noticed“dark blobs struggling in the murkywaters” of the Mississippi near PineBend. They were ducks caught infloating oil. He, his father, George,and his mother, Dorothy, decided torescue as many ducks as they could.By midnight they had hand washed38 in their basement. Then GeorgeSerbesku, a stockyard livestock-weigher, carried two bushel-basketsfull of dead and oily ducks to thestate capitol and asked for help. He

called newspapers and television sta-tions, making a plea for volunteers,boats, and governmental action. Atfirst, federal fish and wildlife officersthreatened to arrest him for han-dling wild birds, but soon they is -sued capture permits and joined therescue operation.16

Oiled ducks die from drowning(because coated feathers lose buoy-ancy), from exposure (because bodyheat is lost through oiled feathers),from starvation and predation(because mobility is reduced), fromintestinal lesions and acute oil toxic-ity, and from suffocation (when oillodges in nostrils and throats). OnSaturday March 31, rescuers found172 oil-soaked dead ducks in theriver near Hastings. Another 300were caught and washed. Dead

beavers, geese, and muskrats werealso found. Each day the death tollfor ducks mounted.17

Conservation officers attributedmost of the duck mortality to thesoybean oil. Being more volatile andbuoyant, the petroleum oil bothevaporated and moved more rapidlydownstream. The soybean oil, whichbegan as “thick, orange-coloredslicks,” changed to sticky, “pliablegrayish and somewhat rubbery float-ing masses.” Blown to shore, it sankin quiet-water areas or weathered toa taffylike material.18

The November 1962 race for

governor had been a cliffhanger. Itwas not until March 25, 1963, thatKarl Rolvaag was sworn in after aseries of recounts. On April 1 heordered state agencies to try rescu-ing and rehabilitating the oiledducks. Wardens were called in fromas far as 200 miles away. “Ducklaundries” were set up at the ComoZoo in St. Paul and Carlos AveryGame Farm.19

The Department of Conservationmade intensive duck-rescue attemptsin the first days of April. Some 88Game and Fish employees and 15U.S. Fish and Wildlife workerslabored at the duck laundries. Byhand, they washed Duz-brand deter-gent into feathers of birds coveredwith oil that had set to a shellac-likeconsistency. (Dawn is the currentduck-washing detergent of choice).They followed this with a several-minute soak in a solution of trisodi-um phosphate and Calgon watersoftener and then a clean-waterrinse. After washing, the 1,369 res-cued ducks were housed until the fall

Citizen duck rescuers L. W. Rollins and George Serbesku show St. Paul legislatorWilliam L. Shovell some oiled ducks on the steps of the Capitol

Summer 2002 111

when they molted and grew newfeathers. Some 350 survived andflew away.20

On April 3 State Health commis-sioner Robert N. Barr discussed theemergency with the governor’s office.He described the need for legislationgiving a state agency the authorityto prevent such disastrous eventsinstead of merely reacting to them.That same day Rolvaag toured thewildlife area and stated: “We willfind the funds to care for the prob-lem. Certainly a society as affluent asours can spare a buck to save a duck.”The governor appointed MichaelCasey, a regional game manager, totake charge of operations. Whencon cerns rose about the threat to600–1,000 swans in the WeaverBottoms backwater below Wabashain Lake Pepin once the ice dambroke, the governor continued, “Thisdemonstrates the need for strongerwater pollution control legislation.I will throw my weight behind it.”Rolvaag was joining the state’s on -going, contentious debate sparkedby deteriorating river quality andchanging expectations about the useof natural resources.21

Strong public and editorial opin-ion erupted after the duck devasta-tion became known. Writers for andto the Red Wing Republican Eaglewere especially outspoken: “Thesilent death now floating down theMississippi calls for strong action.”“No one who has seen the vast de -struction carved by these floatingsheets of oil could possibly opposelegislation to prevent such carnagein the future.” An April 12 editorialurged: “What’s needed is to give astate commission, possibly the water

George Serbesku shows Governor Karl Rolvaag the spills’s effects on ducks at SpringLake on the Mississippi River, April 2

112 Minnesota History

pollution control unit, the power torequire industries and communitiesto take adequate safeguards againstsuch examples of pollution.” Thenext day, the paper continued, “TheState is like a toothless old sow witha hard ear of corn.” Many Minne -sotans began sending money to thegovernor’s “Buck for a Duck” fund.Donors included schoolchildren anda woman who mailed $5.00 previ-ously earmarked for an Easter bon-net. She said she could not enjoy thehat while thinking of the dying ducks.22

Amid the heated rhetoric, Gov -ernor Rolvaag on April 4 issued thefirst executive order of his new ad min-istration. It activated the Nation alGuard to rescue ducks and recoveroil, capping expenses at $14,000.Fifty men of Northfield’s CompanyD of the 682nd Engineers Battalionwere mobilized under Lt. Col. Don -ald Crowe, who said, “We’re playingit by ear, no one has written a bookon it yet.” On April 6, another 75men from Company A, as well asmembers of the Coast Guard, joinedthem. Eventually 24 officers and 124enlisted men were brought in for oiland duck operations.23

Oil spilled on water floats,

hence the saying, “Oil and waterdon’t mix.” But over time, somefloating oil dissolves into water—andthe most toxic constituents of petro-leum oil are generally the most solu-ble. The most volatile constituentsevaporate, sometimes creating a firehazard and leaving gummier oilbehind. Oil will also emulsify intowater, especially in wind or overrapids or a dam. This turbulencecreates a semifloating, gelatinous

goo or “mousse,” which is very hardto recover. With continued weather-ing, this oil can sink or be strandedin a band along shorelines. Overmonths or years, the action of natur-al microbes will eventually degrademost oils.

In 1963 little was known abouthow to respond to oil spills, soAmerican ingenuity was called intoplay. National Guardsmen and vol-unteers tried fashioning contain-ment booms by tying together logsand poles. They chained togetherfloating oil drums and hung burlapfrom the chains to absorb and de -flect the floating oil. They spreadstraw on water to sop up oil andstuffed straw into wire netting tomake sorbent booms. They pumpedoil from the water using small port -able pumps on shore or in boats,temporarily storing oil in drums orin metal culverts suspended vertical-ly in the water. Crews tried industri-al detergents to disperse oil. Theyhazed waterfowl with airplanes andgunshots and dropped corn in cleanareas to move them away from oilyspots. They tried burning off the oil,including on-land burning at theRichards plant. A proposal to sus-pend a natural-gas-fired jet over theriver to burn oil as it floated past wasconsidered but rejected.24

By the weekend of April 6–7, how-ever, only a few days after Rolvaag’sexecutive order, the National Guardconcluded that it had been called intoo late and was having no apprecia-ble success at removing oil from themain channel of the MississippiRiver or at saving birds. Thereafter,it concentrated on keeping oil out ofbackwater nesting areas in Sturgeon

Lake, North Lake, Spring Lake, andWeaver Bottoms.25

An April 12 letter from NationalGuard Sgt. Stanley J. Hille to Rol -vaag described the frustration ofguardsmen who were assigned torecover oil that had already done itsdamage and gone downriver. He rec-ommended that they be pulled off“Operation Quack Quack” andallowed to return to their jobs. Theguard deactivated on April 16.26

Follow-up studies showed that theoil eventually moved as far down-stream as La Crosse, Wisconsin,approximately 250 river miles fromMankato. Dissolved soybean oil wasdetected at Rock Island, Illinois.Among the most heavily oiled areaswere the Red Wing Boat Marina andthe Wisconsin side of Lake Pepin,where winds blew oil to shore.27

Some 2,745 dead ducks had beenremoved from the water: Two-thirdswere lesser scaup, one-sixth ring-necked ducks, and one-tenth cootsand grebes. The total of dead ducks“seen but not collected” was 8,003.More than 10,000 waterfowl proba-bly were killed, along with 26 beaver,177 muskrats, and turtles, songbirds,and fish.28

As April continued, oil moved on,sank, or became less sticky, andwaterfowl mortality waned. Overallcosts of the state’s response to thespills eventually totaled $35,000.The conservation department set thenumber of provable duck deaths at3,211. Using a federal “duck value” of$12, the provable wildlife damagetotaled $38,532.29

Pollution laws today require

companies to take steps to prevent

Summer 2002 113

spills and to be prepared to deal withthem, both by reporting the spillsimmediately and by recovering thespilled material. Most abovegroundstorage tanks are now surrounded bydikes that prevent liquids from run-ning to water or seeping into soiland groundwater. In 1963, however,there were no regulations for spillprevention or protection. There wasno requirement that spills be report-ed to health or pollution authorities,or even cleaned up unless there werean immediate public-health threat.

It was several months after theRichards and Honeymead spills,then, that the state’s Water PollutionControl Commission (WPCC) meton March 28 to consider possibleaction against the companies. Legalcounsel for the commission and theDepartment of Conservation advisedthat Minnesota’s Water PollutionControl Act of 1945 did not apply,since the spills were an accidentalloss of a valuable commodity, not acontinuing discharge of industrialwaste. Public-health laws did not

apply either, since no drinking-water supply was affected. Criminalstatutes related to harming wild ani-mals or creating a public nuisancerequired proof that some personknowingly caused the discharge ofoil. WPCC commissioners were alsoreluctant to enforce any action forfear that the companies would haltthe modest voluntary measures they

National Guardsmen fashion collection booms from barrels and burlap bags, April 7

114 Minnesota History

were now taking to prevent acciden-tal oil spills. Walter Mondale, Min -nesota’s attorney general who wouldbe elected U.S. senator that year,later recalled that the obvious lackof pollution laws and programsdemonstrated to him the need forstrong federal water-pollution legis-lation.30

At the time, federal laws were asweak as state laws. The 1899 Riverand Harbor Act, commonly calledthe Refuse Act, was intended to pre-vent the dumping of material intostreams where it might impede navi-gation. It remained largely unen-forced until the mid-1960s, whenactivists began to press for federalpollution prosecutions.31

The death of 10,000 ducks re -vealed the weakness of Minnesota’slaws to a public whose expectationsof environmental quality were rapid-ly changing. Rachel Carson’s SilentSpring, an exposé of the pesticidepoisoning of the water supply andbird population, had jolted thenation’s ecological consciousness in1962. Sweeping changes in environ-mental regulation—in part triggeredby these two spills and the dyingducks—were clearly in the cards.

Throughout the nineteenth

century, much of Minnesota’s sew -age, garbage, and industrial wastehad been dumped directly into theground or into streams and rivers tomake it “go away.” Privies, cesspools,night-soil carts, and dumping in thegutters, however, caused sickness,noxious odors, and polluted wells.A number of severe waterborne epi-demics in Minnesota led to the cre-ation in 1872 of the State Board of

Health and the state’s first water-pollution legislation in 1885. Still,sawdust from Minneapolis millsclogged landings and impeded navi-gation in St. Paul and farther down-stream. By the late 1880s Minne -apolis and St. Paul were each dump-ing 500 or more tons of garbage intothe Mississippi River each day.32

Four decades later, the Twin Citieswere discharging raw sewage fromabout 680,000 people directly intothe Mississippi. Industrial wastesand offal from slaughterhouses inSouth St. Paul increased river pollu-tion. Nevertheless, as late as 1928,state sanitation engineers and healthofficials declared: “One of the impor-tant uses of a stream is to care forthe liquid wastes of a communityand it is only natural that the largercities and industries are located onthe banks of streams so that theirwastes may be disposed of in themost economical manner.”33

Ironically, during the first decadesof the century a public-health victorypostponed progress in pollution con-trol. Improved techniques of purify-ing drinking water by filtration andchlorination dramatically reducedwaterborne disease. In effect, thislessened the urgency of aggressivelyregulating waste disposal intorivers.34

Exacerbating the Twin Cities’ pol-lution problem were the locks anddams on the Mississippi River.Locks and Dam #1 built in 1914 nearSt. Paul’s Ford plant created a poolof water that backed up as far asdowntown Minneapolis. Sewage dis-charged into this quiet water settledout in massive sludge deposits 15 ormore feet deep and estimated to be

3 million cubic yards in volume in1928. Most river species cannot tol-erate gross pollution, but somethrive on it. That year an estimatedquarter-million tubificid worms persquare yard inhabited the septicsludges above the Ford dam; fewother species tolerated the toxic,oxygen-poor water of the metropoli-tan river. Farther upstream near theWashington and Franklin Avenuebridges, even these species wereabsent, apparently killed by wastefrom the coal gasification plant justupstream (near the current Inter -state 35W crossing).35

The metropolitan area’s sole majortreatment facility was completed in1938 at Pigs Eye Lake south of St.Paul. By 1945 only one-fifth ofMinnesota’s population was servedby sewage-treatment works with sec-ondary treatment (considered basictoday). Just one-third of 700 indus-trial plants in the state that dumpedwaste directly into surface watershad any treatment.36

In 1945 the legislature passed theWater Pollution Control Act thatcreated the Department of Health’sWater Pollution Control Commis -sion (WPCC). Authorized to reviewplans and issue permits for sewageor waste-disposal systems and ordersfor pollution abatement, the com-mission worked on an “informal andad hoc basis,” staffed at the begin-ning by four professionals and oneclerical from the health department.37

In the first half of the century,

when public-health officials and san-itary engineers had sought only toeliminate waterborne disease andtreat sewage so that water could be

Summer 2002 115

disinfected for drinking, little thoughtor value was given to protectingwaterways for their own sake. Asliving standards increased, the grow-ing outdoor-recreation movementbroadened the desired uses of streamsto include fishing, camping, andpleasure boating. Conservation andsportsmens’ groups such as the IzaakWalton League (formed in 1922)began to press for tougher pollutionregulation to support hunting andfishing while still permitting indus-trial uses of waterways such as papermilling.38

By the 1950s, however, even withinterceptor sewers and the Pigs Eye

treatment plant, a burgeoning popu-lation and industrial operations ledto worsening conditions in Minne -sota’s rivers. The metropolitan Mis -sis sippi River was still a stinkingstream devoid of fish, with floatingsludge mats, bottom sludge severalfeet deep, and gasses rising to thesurface. Inadequate septic tanks pol-luted shallow wells. Not surprisingly,the WPCC came under increasingcriticism for failure to stem pollution,especially in the Twin Cities whereits treatment plant had reached vol-ume capacity.39

In addition, writes historianThomas Huffman, WPCC officials

were “infused with a professionalethic that characterized pollution asa technological matter best resolvedby quiet mediation over a period oftime.” They believed, as ChesterWilson, former commissioner ofconservation and attorney for theWPCC, opined, “An ounce of cooper-ation is worth a pound of compul-sion.” Considering its tiny size andthe daunting challenges, the WPCCstaff probably did yeoman’s work ina difficult situation.40

Among the commission’s harshestcritics were Senator Gordon Rosen -meier of Little Falls and Repre sent a -tive Donald Wozniak of St. Paul.

Constructing sewers, a link to the Twin Cities’ treatment plant at Pig’s Eye, 1937–38, under the railroad tracks near downtown St. Paul

116 Minnesota History

Rosenmeier, a conservative conser-vationist, was a highly influentialmember of the legislature. Wozniakwas the attorney for the Minneapolis-St. Paul Sanitary District. The legis-lators’ efforts to create a metropolitan-wide sewer authority and to buildthe strength of the WPCC had fal-tered in 1961. Rosenmeier was espe-cially frustrated by the WPCC’s lackof aggressive action.41

Two years of hearings in the stateSenate followed the legislature’s1961 failure to strengthen water-pollution-control laws. Differencesbetween urban and growing subur-ban interests were stalling consen-sus. According to the MinneapolisStar, on one occasion, committeemembers exploring a bill came outof the hearings

awed by the sort of suburban devel-

opment that had been permitted to

take place and by the failure of . . .

state health authorities and the local

governments to prevent the near-

crisis that had been reached . . . with

tens of millions of dollars invested

in utterly inadequate on-site facili-

ties, and with some 300,000 people

trying at the same time to bury their

sewage in their back yards and to

draw their water from increasingly

polluted shallow wells.

Almost half of 63,000 wells sampledin the unsewered areas of the TwinCities in 1960 were contaminated bysewage.42

On January 30, 1963, Rosen -meier’s pollution-control bill wasformally introduced as Senate File243. It authorized the WPCC toorder the abatement of sewage and

industrial wastes. If a municipalityfailed to comply, the commissioncould secure a court order or thestate could take over the city’s sewage-treatment function. The state wouldthen design facilities, levy local taxesand assessments, acquire property,and supervise construction of theneeded facilities. The bill containedprovisions on waste-water dischargeto protect the recreational use of thewaters, included groundwater pro-tections for the first time, and madeit possible to revoke permits. Despitethe Richards spill one month earlier,however, the bill did not mentionsafeguards for storage tanks, spillreporting, or spill cleanup.43

Charles Horn’s Minnesota Emer -gency Conservation Committee, aprivate initiative, persistently criti-cized the state’s weak water pollution-control programs. It later describedthe draft Rosenmeier bill favorably:

“It precludes any more stalling. . . .The Commission will have no roomfor alibis for inaction.”44

It was at this point in the debatethat ducks began to die, but SenatorRosenmeier did not seem imme -diately to grasp the opportunityhanded him by the Honeymead andRichards spills. On April 3, Rosen -meier replied to Rolvaag’s inquiryabout whether his bill could prevent“situations like that which occurredthe other day when a burst pipelinecaused extensive damage to waterand wildlife” by saying, “Accidentswhich cannot reasonably be foreseenare not within the focus of the billeven though pollution might result.”Rosenmeier believed his bill “wentabout as far as practicable” but in -vited the governor to suggest ways tostrengthen it.45

Public opinion seemed to disagreewith Rosenmeier’s limited assess-ment. A WTCN television editorialdecried the oil pollution, while not-ing that sewage pollution was “lessspectacular but more dangerous.” Iturged passage of the “vitally needed”Rosenmeier bill. The Red WingWildlife Protective League praisedthe Rosenmeier bill and asked thelegislature to go even further in “get-tough” legislation to curb pollution.The Grand Rapids Herald observedthat Minnesota had “weak laws gov-erning pollution,” while the SwiftCounty News proclaimed, “Perhapsthe dead ducks along the Mississippiwill bring action on the continuingpollution problem that is a shameshared by everyone in the State.” AMankato Free Press article head-lined “Death of Ducks ‘Blessing inDisguise’” quoted Representative

Gordon Rosenmeier, the state senatorfrom Little Falls whose pollution-controlbill became law

Summer 2002 117

Arlen I. Erdahl as saying: “Perhapsthe legislature will now pass a pollu-tion bill with some teeth in it.”46

Agitating for stronger state guide-lines, citizens criticized governmentand industry. An editorial in theWabasha Herald declared that thepeople who are responsible “shouldbe here running our ‘duck laundries’and cleaning up our shorelines.Aren’t the oil tank farms responsiblefor letting this stuff get away?” TheRed Wing Republican Eagle pushedfurther, observing: “What’s needed isto give a state commission. . . . thepower to require industries and com -munities to take adequate safeguardsagainst such examples of pollution.”47

Governor Rolvaag received manyletters supporting pollution-controlprograms, including petitions fromseventh-grade classes. One letterwriter claimed, “We wait until disas-ter strikes to become alarmed. Thisis the Atomic bomb for wildlife andwe allowed it to happen.” Rolvaagresponded to one Red Wing writerthat state agencies were powerless toprevent these disasters but that “newlegislation should ideally change thissituation completely.”48

On April 5, 1963, the Rosenmeierbill passed the Senate for the firsttime without language coveringspills or spill prevention, but newbills introduced on April 22 and 23squarely addressed prevention andresponsibility for spills. HF 1907authored by Samuel R. Barr ofOrtonville and SF 1783 authored byBenjamin B. Patterson of Deer Riverdeclared a stored polluting substanceto be a “dangerous instrumentality”and provided that the owner of thesubstance and the storage facility

Representative Donald D. Wozniak (with Rep. Richard W. O’Dea, standing), leader ofthe fight for pollution-control legislation in the House

would be liable jointly to the statefor expenses incurred to remove pol-luting substances from waters or toconfine the area of pollution. Whilethese bills did not get out of theirfirst committee meetings, theirassign ment of liability to owners ofsubstances and facilities presagedthe federal and state “Superfund”cleanup laws by some 17 years.49

On May 2, Representative Woz -niak introduced HF 1969, a bill withsimilar features that required a per-mit for storing more than 25,000gallons of liquid. It likewise did notpass out of committee.50

The next day Wozniak offered asuccessful amendment to theHouse’s version of Rosenmeier’sSenate bill authorizing the WPCC to

require safeguards at liquid-storagesites. The amendment authorizedthe commission to issue orders“prohibiting the storage of any liquidin a manner which does not reason-ably assure proper retention againstentry into any waters of the state.”51

Concerns about the state usurpingthe power of local sewer authoritiescontinued, and an amendment limit-ing the Rosenmeier bill to Ramsey,Hennepin, St. Louis, and contiguouscounties was introduced but failed.On May 22, 1963, Rosenmeier’s billbecame law, passing the Senate by aresounding 59 to 1 and the House by83 to 44. The final law contained therequirements for liquid-storage safe-guards. It also included the conten -tious municipal sewage-treatment

118 Minnesota History

takeover provisions and expandedthe definition of state waters to in -clude underground waters. Accord -ing to one press release, “There weredetermined efforts to amend the billto death, but the calamitous oil pol-lution disaster in the Minnesota andMississippi Rivers made it top mustlegislation.”52

Even after passage of the new law,Wozniak remained skeptical of theWPCC’s willingness and ability toregulate potential pollution sources.During the summer of 1963 he

arranged for volunteers to surveystorage-tank facilities in order topressure the commission to enactaggressive regulations that carriedout the intent of the new law. Hisvolunteer crew found a number ofsites along the river in St. Paul withno dikes or with inadequate diking,and a commission field survey ofaboveground storage facilities acrossthe state showed that 93 percentlacked diking. While the largest weremore likely to be diked, many ofthose without dikes were near sur-

Doing business in the Senate chamber, mid-1960s

face waters or municipal drinking-water intakes.53

The state legislature frequently

passes laws that create a basic regu-latory framework, allowing depart-ments to conduct hearings and writethe details into rules. In the monthsthat followed passage of the law,stakeholders in the debate continuedto lobby for their interests. The Min -nesota Petroleum Council, for exam-ple, urged that industry be permittedto set its own storage-tank standards.

MODERN OIL-SPILLSTRATEGIES

■ Floating plastic booms made oflong sections of plastic-wrappedfloat chained together. A “skirt”hangs down from the float intothe water to contain the oil.

■ Skimming devices, includingvacuum trucks (like a giant shopvacuum) or floating weirs.

■ Oleophilic (oil-loving) sorbentplastics fabricated into floatingpads, sausage-shaped booms, orpillows that soak up oil.

■ Dispersants, or detergents thatdissolve floating oil in oceanwater. This is an extreme lastresort in bodies of fresh water,many of which are used fordrinking.

■ Intentionally set fires thatquickly remove large amountsof oil from water but create airpollution and leave a sticky,difficult-to-manage residue.

Cleanup worker lifting stringy oilaccumulation, Mississippi River

The WPCC declined this proposaland, instead, after meeting withvarious industrial and agriculturalinterests, drafted detailed rules forliquid-storage safeguards. Further,at a St. Paul rule-making hearingon April 8, 1964, the commissiondescribed potential surface-waterpollution from uncontained spillsand also noted that rules protectinggroundwater from seepage of spillsmight be even more important thanthose protecting lakes and streams.54

The citizens’ organization ClearAir—Clear Water Unlimited, oncevery critical, now complimented thecommission on its draft liquid-storagerules. The City of St. Paul testi fied infavor, while the St. Paul Port Au thor -ity, which managed the city’s river-front, opposed the rules. Rail road andagricultural interests also challengedthem, indicating concern about costand the effectiveness of dikes.55

The Petroleum Council, represent-ing operators of large storage andtransportation facilities, touted the“near perfect record maintained bythe petroleum industry” in prevent-ing water pollution in Minnesotaand elsewhere. The council testifiedthat because the state fire marshal’sflammable-liquids code requireddikes and because other industrypractices designed to prevent tanksfrom leaking were more appropriateand effective, there was a “completelack of need for the sealing of dikedareas.”56

On June 26, 1964, the WPCCnonetheless adopted a set of rules,known as Regulation WPC4. It pro-hibited storage of liquid material“without reasonable safeguards ade-quate to prevent the escape or move-

ment of the substance” when pollu-tion of any state waters might result.Facility owners were required toobtain a permit from the WPCC,and minimum safeguards were toinclude a continuous dike or wallenclosing an area sufficient to con-tain the largest tank’s contents and“a reasonably impervious bottom”under the entire site. While the regu-lation was silent on the constructionand operation of tanks, it re quiredthe owner of a liquid-storage facilityto notify the WPCC of “any loss ofstored liquids either by accident orotherwise” if the substance would belikely to enter any state waters.57

The value of aboveground storage-tank diking was soon demonstrated.In December 1964, heavy rain fell inSt. Paul. Water collected in the dikedarea surrounding a 4-million-gallondiesel-oil tank at the Mobil Oil tankfarm off West Seventh Street. In the

Summer 2002 119

MINNESOTA’SBIG SPILLS

The damage ultimately caused by aspill is a unique combination ofmaterial and amount spilled, loca-tion, and good or bad luck.

■ A 1964 spill at the Mobil Oiltank farm in St. Paul that dis-charged 4 million gallons into adiked area appears to have beenthe largest, but it created far lessdamage than the Richards andHoneymead spills of 1962–63.

■ In 1986 the Williams Pipelineleaked 22,000 gallons of gaso-line in a residential section of theTwin Cities suburb of MoundsView. The gasoline ignited, kill -ing two people, injuring severalothers, and causing extensiveproperty damage.

■ In 1991, 1.7 million gallons ofcrude oil flowed out of the Lake -head Pipeline in Grand Rapids.Occurring between a communitycollege and an apartment build-ing, this break had tremendouspotential for loss of life and envi-ronmental disaster, but littlelong-lasting damage resulted.

■ In 1992, 27,000 gallons of vola -tile chemicals spilled in a trainwreck in Superior, Wisconsin.This caused the evacuation ofSuperior and Duluth, surely themost disruptive spill in Min ne -sota’s history.

Source: Minnesota PollutionControl Agency, EmergencyResponse Team files.

bitter cold that followed on Decem -ber 16, a 20-foot crack developed inthe tank, and its entire contentsgushed out. The dikes held, however,preventing a flood of oil from run-ning into the Mississippi River. Theice that coated the diked area pre-vented the oil from immediatelyseeping into the ground. Expertspaddled a boat on the oil pool andwaded through chest-deep oil to in -vestigate the cause of the leak. Emer-gency responders set up portablepumps that, over four days, pumpedthe oil into intact tanks. Thus, whatwas probably the largest oil spill inMinnesota created little immediateenvironmental damage.58

In the years following the rule’sadoption, most large operators pro-vided big aboveground storage tankswith dikes constructed of nearbysoil. These native-soil dikes did notoffer much protection against seep-age, however. Inadequate seals under -neath the tanks often allowed oil todrain into the ground undetected.

Most new tanks constructed after1964 had dikes that provided asealed containment area made ofconcrete or clay soils brought to thesite. Poor maintenance and theinherent shortcomings of earthendikes often meant that even thesefacilities eventually became contami-nated. Few state staff were consis-tently assigned to enforce the rule orpermit requirements.

Under the 1963 Rosenmeier Act,the WPCC had been given broadnew powers to compel municipali-ties to act and to usurp local sewage-treatment control, if necessary.Rosenmeier soon concluded that thelaw was “too strong and too broad

for implementation by the existingunaggressive Water Pollution Com -mission.” Commissioner ChesterWilson himself described it as hav-ing “drastic provisions, but meagerappropriations.” In November 1963the Upper Mississippi PollutionControl Committee, a citizens’ groupwith the motto “We Can’t All LiveUpstream,” organized a meeting inWabasha, Minnesota, attended by150 citizens and state and federalofficials. The group found “an appal -ling lack of a program” and conclud-ed that there was need for a “statepollution control agency whose full-time staff people are dedicated cru-saders for clean water.”59

By the end of 1963, GovernorsJohn W. Reynolds of Wisconsin andRolvaag of Minnesota were, in fact,requesting federal help in evaluatingand cleaning the upper MississippiRiver. A Minnesota-Wisconsin-federal pollution conference heldin St. Paul in 1964 was followed bythe formation of the Minnesota-Wisconsin Boundary Area Com mis -sion to coordinate water-pollutionprograms and plans. In December1964 an internal governor’s officememo lamented the “continuinginadequacies of the MinnesotaWPCC and its administrative arm,the Minnesota Department ofHealth under Dr. Barr.”60

During the 1965 session, legisla-tors debated a bill to create an inde-pendent pollution-control agency.Although vigorously opposed bythe health department and severalothers, it passed both houses. Ulti -mate ly, though, the bill failed in thesession’s final midnight hour as Rep -re sentative Wozniak and Senator

120 Minnesota History

Summer 2002 121

Notes1. Information on the Richards spill is

from: Minnesota Dept. of Health, Environ -mental Sanitation Div., “Oil Pollution ofMinnesota and Mississippi Rivers Duringthe Winter of 1962 and Spring of 1963,”Apr. 17, 1963 [hereinafter, MDH Oil Pol -lution], 1–4, and Appendix 2, Exhibit 9B—both in “Water Pollution Control-4 LiquidStorage, Apr. 15, 1964” folder, Hearing files[hereinafter, WPC-4 hearing], MinnesotaPollution Control Agency (PCA), WaterQuality Div., State Archives, MinnesotaHistorical Society (MHS), St. Paul; GordonC. Moosbrugger to Walter F. Mondale,“Chronology of Richards Oil CompanyPollution”, Apr. 19, 1963 [hereinafter, Apr.19 Richards memo], “Water Pollution—Operation Duck Rescue” folder [herein -after, Duck Rescue folder], ConservationDept., 1963, Gov. Karl F. Rolvaag Papers,State Archives; Moosbrugger to Mondale,

“Richards Oil Company Pollution Prob -lem,” Apr. 10, 1963 [hereinafter, Apr. 10Richards memo], Water Pollution ControlCommission (WPCC) folder, Subject Files:1962–63, Minnesota Attorney General,State Archives; U. S. Dept. of Health, Edu -cation and Welfare, “Report on Oil SpillsAffecting the Minnesota and MississippiRivers, Winter of 1962–63” [hereinafter,HEW Report on Oil Spills], 2—4, Exhibit9D, WPC-4 hearing.

2. MDH Oil Pollution, 1; HEW Reporton Oil Spills, 3.

3. MDH Oil Pollution, 2; HEW Reporton Oil Spills, 3; Apr. 19 Richards memo;Apr. 10 Richards memo.

4. MDH Oil Pollution, 2; HEW Reporton Oil Spills, 4; Apr. 19 Richards memo,1–3; Apr. 10 Richards memo.

5. MDH Oil Pollution, 2–4, andAppendix 2; Apr. 10 Richards memo.

6. Information on the Honeymead spillis from MDH Oil Pollution, 2–6, and App.2; Moosbrugger to Mondale, “Collapse ofHoneymead Products Inc. soybean oil stor-age tank at Mankato, Minnesota,” Apr. 19,1963 [hereinafter, Apr. 19 Honeymeadmemo], Duck Rescue folder, Rolvaagpapers; HEW Report on Oil Spills, 4–6;Mankato Free Press, Jan. 23, 1963, p. 1, 2,19; Edward Ward, interview by author,May 9 (telephone), June 1, 2000, Mankato.Harvest States still operates the Honey -mead plant.

7. Paul Andersen, University of Minne -sota Institute of Technology, to Moos brug -ger, Apr. 24, 1963, in Duck Rescue folder,Rolvaag papers; Ward interviews; HEWReport on Oil Spills, 5; Apr. 19 Honeymeadmemo.

8. Ward interviews.9. Gerald Erkel, interview by author,

Rosenmeier could not agree onwhether the state’s conservationcommissioner would serve on thenew pollution-control board andwhether former WPCC staff wouldbe part of the new agency.61

In 1967, the fight over the fate ofthe WPCC resumed. In defense of thecommission, Chester Wilson arguedthat it was “an outrageous injustice”to blame the commission whenthings went wrong because the legis-lature “won’t provide adequate funds”and because it “tries to cover up itsshort-comings by reorganizing.” Afterfour months of hearings and meet-ings, the legislature on May 18 passedSF 845, creating the Min nesota Pol -lution Control Agency (PCA). Votestallied at 129-0 in the House, where itwas sponsored by conservative AlfredFrance of Du luth, and 63-0 in theSenate, sponsored by Rosenmeier.The bill severed the connection ofthe health department from the newpollution-control agency, strength-

ened water-pollution provisions, andauthorized programs to control airpollution. Representative France andother House members worried thatauthorized salary levels might notattract an adequate staff but notedthat the proposed $1 million two-yearbudget would be more than threetimes the amount appropriated to theWPCC. Although some, includingRosen meier, were disappointed whenthe staff from the old WPCC wastransferred to the new PCA, theauthorities and staffing for the newagency far exceeded those everaccorded the WPCC.62

The summer after the failed

Operation Save a Duck, WPCCCommissioner Wilson reflected:

Oil made a nasty mess while it

lasted, but it was soon up and soon

over. . . . However, there is a highly

significant lesson to be drawn from

these events. It is that . . . action on

public affairs that cost much money

is seldom taken unless the people

and their representatives . . . are

stirred to move by some heavy loss

or calamity. . . . If the loss of a few

thousand ducks should result in

impelling the Minnesota Legislature

to put up what it takes for a really

effective water pollution control

program, it will be a very small

price to pay for such a momentous

achievement.63

Individual incidents producingpub lic outrage have triggered mostbroad state and federal environmen-tal-protection programs. Such wasthe case with the Minnesota legisla-ture’s response to oiled ducks on theMississippi River. Although theRichards and Honeymead spills ofthe cold winter of 1962–63 are nowlargely forgotten, they played a largerole in framing the structure ofenviron ment al protection inMinnesota today. ;

122 Minnesota History

Apr. 24 (telephone), June 1, 2000, NorthMankato.

10. Erkel interview; Evelyn Herman,telephone interview by author, May 9,2000; Mankato Free Press, Jan. 23, 1963,p. 1.

11. MDH Oil Pollution, 4, 5; HEWReport on Oil Spills, 6; Apr. 19 Honeymeadmemo; Mankato Free Press, Jan. 23, 1963,p. 1, and Jan. 24, 1963, p. 1.

12. Information on the duck rescue andmortality is from HEW Report on OilSpills, 30–36; MDH Oil Pollution, 4–10,and App. 2; Minnesota Dept. of Conser va -tion, Game and Fish Div., “Report onWaterfowl Mortality Caused by Oil Pollu -tion of the Minnesota and MississippiRivers in 1963,” Jan. 1, 1964 [hereinafter,Waterfowl Mortality report], 1–2, “Pollu -tion (2)” folder, Dept. of Conservation,State Archives.

13. Apr. 19 Richards memo, 3; Minne -apolis Tribune, Apr. 1, 1963, p. 1; MDH OilPollution, App. 2.

14. Mankato Free Press, Apr. 1, 1963, p.19; MDH Oil Pollution, 6–7; HEW Reporton Oil Spills, 5, 31; Apr. 19 Honeymeadmemo, 2.

15. Mike Korneskie, interview byauthor, Oct. 13, 2000, Hastings; HEWReport on Oil Spills, vi.

16. Edith Peller, “Operation Duck Res -cue,” Audubon Magazine 65 (Nov. 1963):365–67; George Serbesku, telephone inter-view, Aug. 31, 2000. Serbesku related thatGovernor Rolvaag said he had come toobserve the rescue operation to “see whohad pushed him off of the front pages.”

17. HEW Report on Oil Spills, 9;Mankato Free Press, Apr. 1, 1963, p. 19.

18. Waterfowl Mortality report, p. 219. Mankato Free Press, Mar. 22, 1963,

p. 11, and Mar. 25, 1963, p. 1; MinneapolisTribune, Apr. 2, 1963, p. 1; MDH Oil Pol -lution, 4–6, and App. 2; HEW Report onOil Spills, 4–6; Waterfowl Mortality report,1–2; Peller, “Operation Duck Rescue,”365–67.

20. Waterfowl Mortality report, 1–5;Peller, “Operation Duck Rescue,” 365–67.Controversy continues about whethercleaning and rehabilitating oiled ducks andwildlife is worth the cost, effort, and suffer-ing. Only a minority survives. In Canadaeuthanasia is routinely practiced.

21. Duck Rescue folder, Rolvaag papers;Peller, “Operation Duck Rescue,” 365–67;Minneapolis Tribune, Apr. 3, 1963, p. 1.

22. Red Wing Republican Eagle, Apr. 1,1963, p. 1, Apr. 4, 1963, p. 1, Apr. 12, 1963,p. 1; Waterfowl Mortality report, 5.

23. Minneapolis Tribune, Apr. 4, 1963,p. 1; Dept. of Military Affairs, Minnesota

National Guard, “Final Report to GovernorRolvaag” and “After Action Report of Lt.Col. Donald Crowe,” Apr. 24, 1963, [here-inafter, Military Affairs Reports], Exh. 2A,WPC-4 hearing.

24. See Minneapolis Tribune, Apr. 2,1963, p. 1B, Apr. 3, 1963, p. 1, 10, Apr. 4,1963, p. 1, 8, Apr. 6, 1963, p. 5, Apr. 7,1963, p. 18; Mankato Free Press, Apr. 4,1963, p. 1; Military Affairs Reports; Peller,“Operation Duck Rescue,” 365–67; HEWReport on Oil Spills, 8–9; proposal, DuckRescue folder, Rolvaag papers.

25. Military Affairs Reports.26. Stanley Hille to Governor Rolvaag,

Apr. 12, 1963, and Governor’s Office, pressrelease, Apr. 16, 1963, in Duck Rescue fold-er, Rolvaag papers. Even today, a recoveryrate of less than 20 percent is common.

27. HEW Report on Oil Spills, 13–22;Mankato Free Press, Apr. 4, 1963, p. 1;Minneapolis Tribune, Apr. 7, 1963, p. 1B;Military Affairs Reports.

28. Waterfowl Mortality report, 5;Peller, “Operation Duck Rescue,” 365–67.

29. Military Affairs Reports; Clear AirClear Water Unlimited Newsletter (SouthSt. Paul), Feb. 1964, in “Pollution (2)” fold-er, Dept. of Conservation.

30. WPCC, Statement for Conferenceon Interstate Pollution of the MississippiRiver, Minnesota Dept. of Health, Feb. 6,1964, Water Pollution folder, Legislativefiles, 1963, Gordon Rosenmeier papers,MHS; WPCC, “Long Range Water Pollu -tion Control Plan and Program, 1963,” Exh.9G, WPC-4 hearing; Apr. 19 Richardsmemo; Apr. 10 Richards memo.

According to Richards’ family lore,when Mondale visited the Richards site inthe spring of 1964 to observe the cleanup,he was “cold-cocked” (knocked out) by oneof the Richards brothers for loudly criticiz-ing the company. Mondale does not recallvisiting the site or being the victim of anassault. Jeff Richards, telephone interview,Feb. 28, 2000; Walter Mondale, telephoneinterview, May 9, 2000.

31. Although several Refuse Act prose-cutions around the country succeeded, theproblems of implementing the act led topassage of the federal Water PollutionControl Act of 1972, which represented abroad expansion of federal powers. Minne -sota Congressman John Blatnik is consid-ered the “father” of the federal act in theHouse. See Harvey Lieber, Federalism andClean Waters (Lexington MA: D.C. Heath,1975), 24; Joan C. Kovalic, The CleanWater Act of 1987 (Alexandria, VA: WaterPollution Control Federation, 1987), 9.

32. Joseph Petrula, EnvironmentalProtection in the United States (San Fran -

cisco: San Francisco Study Center, 1989),copy in Dept. of Natural Resources library,St. Paul; Terence Kehoe, Cleaning Up theGreat Lakes—From Cooperation to Con -frontation (DeKalb, IL: Northern IllinoisUniversity Press, 1997), 18–19; PCA, Min -nesota Pollution Control Agency, 1967–76(St. Paul: MPCA, 1977), 1, copy in PCAlibrary, St. Paul; Minneapolis Star Tribune,Apr. 5, 1999, p. A8; WPCC, “Long-rangeplan and program to be submitted to the1965 Legislature,” 1963, p. 1 [hereinafter,“Long-range Plan”], preliminary draft,Exh. 9G, WPC-4 hearing.

33. Minnesota State Board of Health,“Report of the Investigation of the Pollu -tion of the Mississippi River, 1928” [here-inafter, “Report of Pollution, 1928”], 9–10,in Metropolitan Drainage Commission ofMinneapolis and St. Paul, Second AnnualReport, 1928, Metropolitan Waste ControlCommission, Annual and Biennial Reports,State Archives.

34. Kehoe, Cleaning Up the GreatLakes, 18–19.

35. “Report of Pollution, 1928,” 31, 66, 68.36. MPCA 1967–1976, p. 2; WPCC,

“Long-range plan,” 5–6, Exh. 9G, WPC-4hearing.

37. Lovell Richie, telephone interviewby author, Jan. 24, 2000.

38. Thomas R. Huffman, Protectors ofthe Land and Water: Environmentalism inWisconsin, 1961–68 (Chapel Hill: Univer -sity of North Carolina Press, 1994), 7–8;Kehoe, Cleaning Up the Great Lakes,18–19.

39. WPCC, Statement for Conferenceon Interstate Pollution, Rosenmeierpapers; WPCC, “Long-range Plan,” 11–14,17, Exh. 9G, WPC-4 hearing.

40. Huffman, Protectors of Land andWater, 66; Water Pollution—Old Bills fold-er, Chester S. Wilson Papers, MHS. Wilsonwas Minnesota’s first commissioner of con-servation (1943–55) and chairman of theWPCC (1945–52); his papers are invaluablefor studying the history of Minnesotawater-pollution control.

41. MPCA 1967–76; WPCC, Statementfor the Conference on Interstate Pollution,Feb. 7, 1964; Mankato Free Press, Mar. 1,1963, p. 1; Donald Wozniak, telephoneinterview by author, Apr. 22, 2000.

42. Minneapolis Star, undated clipping,“Water Pollution—1963(1)” folder, Rosen -meier papers; Frank L. Woodward, Frank -lin J. Kilpatrick, and Paul B. Johnson,“Experiences with Ground Water Contam i -nation in Unsewered Areas in Minnesota,”Ground Water Contamination 1960 folder,Wilson papers.

43. Minnesota, Jour nal of the Senate,

Summer 2002 123

papers; “Pollution Control—1963” folder,Wilson papers; Upper Mississippi Pollu -tion Control Committee, undated pressrelease, “Water Pollution—1963” folder,Legislative files, Rolvaag papers.

60. “Mike” to Governor, memo, Apr. 20,1964, Duck Rescue folder, Rolvaag papers;Chester Wilson, undated defense of WPCC,“Water Pollution(1)” folder, Rosenmeierpapers; “Pollution Control—1963” folder,Wilson papers.

61. Senate Journal, 1965, SF 1963, p.2818; House Journal, 1965, HF 2192, p.3318; Minnesota Legislature, House, CivilAdministration Committee, records, 1965,and Legislature, Senate, Record of Bills,1965, both State Archives; MinneapolisTribune, May 27, 1965, p. 14B; ElizabethH. Haskell and Victoria S. Price, StateEnvironmental Management: Case Studiesof Nine States (New York: Praeger Publish -ers, 1973), 46.

62. St. Paul Pioneer Press, Mar. 1, 1967,p. 13, May 19, 1967, p. 13; Senate Journal,1967, p. 540, 2417; House Journal, 1967, p.2988, Minneapolis Tribune, May 19, 1967,p. 17. Senator Rosenmeier wrote GovernorHarold LeVander that the legislature didnot intend for the PCA to have a staff “foist-ed on them”; Rosenmeier to LeVander, Aug.15, 1967, “Pollution 1967–68” folder,Rosenmeier papers.

Today, PCA’s roles have expanded toinclude wastewater-treatment enforcement,air-pollution control, hazardous- and solid-waste management, and spill and past-dis-posals cleanup. PCA also provides educationand assistance on pollution prevention.

63. Chester S. Wilson to Upper Mis -sissippi Pollution Control Committee,Red Wing, Feb. 3, 1964, “Water Pollution,1963” folder, Legislative files, Rosenmeierpapers.

1963, SF 243, p. 2515; Minnesota, Journalof the House, 1963, HF 481, p. 2802;“Water Pollution—1963” folder, Rosen -meier papers.

44. Minnesota Emergency ConservationCommittee, press release, June 11, 1963,“Water Pollution—1963(2)” folder, Rosen -meier papers. Charles Horn, president ofthe Federal Cartridge Corporation, formedthis small committee in 1940 after becom-ing frustrated by lack of leadership in theconservation movement.

45. Office memo, Apr. 3, 1963, DuckRescue folder, Rolvaag papers; Rosenmeierto Rolvaag, Apr. 3, 1963, “Water Pollu -tion—1963(1)” folder, Rosenmeier papers.

46. WTCN editorial, “Water Pollution—1963(1)” folder, Rosenmeier papers; RedWing Republican Eagle, Apr. 4, 1963, p. 1,4, 12; Minneapolis Tribune, Apr. 8, 1963,p. 6, including quote from Grand RapidsHerald and Swift County News; MankatoFree Press, Apr. 10, 1963, p. 11.

47. Red Wing Republican Eagle, Apr. 6,1963, p. 1, quoting Wabasha Herald, Apr.2, 1963.

48. Wallace H. Jagusch to Gov. Rolvaag,Apr. 1, 1963, and Rolvaag to M. Davis, RedWing, Apr. 5, 1963, Water Pollution folder,Legislative files, Rolvaag papers.

49. Senate Journal, 1963, SF 1783, p.2710; House Journal, 1963, HF 1907, v. 2,p. 2967.

50. House Journal, 1963, HF 1969, p.2975.

51. House Journal, 1963, SF 243, p.2045; draft legislation, “Water Pollution—1963(2)” folder, Rosenmeier papers; Lawsof Minnesota, 1963, Chap. 874, SF 243, p.1643–44.

52. House Journal, 1963, SF 243, p.2720–23; Senate Journal, 1963, SF 243, p.2443–47; Minnesota Emergency Con ser -

vation Committee, press release, June 11,1963, O. L. Kaupanger, Sec., “Water Pollu -tion—1963(2)” folder, Rosenmeier papers.

53. Wozniak to WPCC, Oct. 4, 1963,and “Summary of Inspection Reports,”Exh. 9I, both WPC-4 hearing; St. PaulDispatch, Apr. 15, 1964, p. 16.

54. Lyle Smith, Statement of Need,WPC-4 hearing.

55. Testimony, William Soules,Minnesota Petroleum Council, Exh. F,WPC-4 hearing. Clear Air-Clear WaterUnlimited, founded by Tom Savage, Mrs.Pearson, and George Serbesku, “agitated”for pollution control; Serbesku interview.

56. Soules testimony, Exh. F, WPC-4hearing. In the 1990s, many large, 1950s-era, aboveground storage-tank facilities(including the area’s two refineries and sev-eral pipeline terminals) were checked andfound to have significant soil and ground-water contamination from spills, overfills,leaks through tank floors, and leaks inpipes and valves.

57. Exh. 2, WPC-4 hearing. While the1964 rules required owners to report spillsfrom tanks, they did not address spills fromother sources such as trucks or pipelines.In 1969 the legislature passed HF 2312/SF2023 as Minnesota Stat. Sec. 115.061,which closed that legal gap, covering spillsfrom trucks, trains, pipelines, barrels, orother containers. Sec. 115.061 also requiredprompt cleanup, closing another gap madeapparent by the Richards spill.

58. Jim Determan, interview by author,Apr. 27 (telephone), Apr. 29, 1999, Fridley;Department of Conservation memo, Dec.22, 1964, in author’s MPCA files; St. PaulPioneer Press, Dec. 19, 1964, p. 13.

59. “The Legislative Interest in OurLakes,” n.d., 43–48, Subject Files, Pollu -tion, 1968–72, Legislative files, Rosenmeier

The aerial view on p. 107 is from the Blue Earth County Historical Society, Mankato. The photos on p. 108 are by Gerald Erkel, North Mankato. The map is by Matt Kania, St. Paul. The following photos are from

the MHS collections: p. 119 from the U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, St. Paul; p. 105 (by TAS), p. 110 (by Sully), and p. 111 (by Buzz), in the St. Paul Dispatch-Pioneer Press News Negative Collection; p. 105 (by Kimball), and p.113 (by Seubert),

in the Minneapolis Star—Tribune News Negative Collection; p. 115 in the Metropolitan Waste Control Commission records, State Archives. The photo on p. 117 is by Jerome Liebling.

Copyright of Minnesota History is the property of the Minnesota Historical Society and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s express written permission. Users may print, download, or email articles, however, for individual use. To request permission for educational or commercial use, contact us.

www.mnhs.org/mnhistory