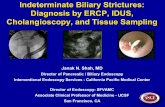

Obstructive Biliary Tract Disease - Europe PubMed Central

Transcript of Obstructive Biliary Tract Disease - Europe PubMed Central

Refer to: White TT: Obstructive biliary tract disease (MedicalAl'edical Progress Progress). West J Med 1982 Jun; 136:484-504

Obstructive Biliary Tract DiseaseTHOMAS TAYLOR WHITE, MD, Seattle

The techniques that have come into general use for diagnosing problems ofobstructive jaundice, particularly in the past ten years, have been ultra-sonography, computerized tomography, radionuclide imaging, transhepaticpercutaneous cholangiography using a long thin needle, transhepatic per-cutaneous drainage for obstructive jaundice due to malignancy, endoscopicretrograde cannulation of the papilla (ERCP), endoscopic sphincterotomy andcholedochoscopy. It is helpful to review obstructive jaundice due to gallstonesfrom a clinical point of view and the use of the directable stone basket for theretrieval of retained stones, choledochoscopy for the same purpose using therigid versus flexible choledochoscopes and dissolution of stones using variousfluids through a T tube.

The use of dilation of the sphincter for the treatment of stenosis or strictureof the bile duct is now frowned on; rather, treatment choices are between theuse of sphincteroplasty versus choledochoduodenostomy and choledochojeju-nostomy. Any patient with obstructive jaundice or anyone undergoing manipu-lation of the bile ducts should have prophylactic antibiotic therapy.

The current literature regarding treatment of cancer of the bile ducts isprincipally devoted to the new ideas relative to treatment of tumors of theupper third, especially the bifurcation tumors that are now being resectedrather than bypassed. Tumors of the distal bile duct are still being resectedby focal operations. Finally, it is now felt that early operation for congenitalbiliary atresia and choledochal cysts gives the best prognosis, with preoper-ative diagnosis now possible with the use of ultrasonography and ERCP.

THE CAUSES of extrahepatic obstruction to the Ascaris lumbricoides. Because jaundice due to bilebile duct include gallstones in the extrahepatic duct obstruction in no way differs from that ofductal system, tumors of the bile ducts and pan- intrahepatic cholestasis, we will begin with a verycreas, bile duct atresia and stricture, choledochal brief discussion of the traditional methods of dif-cysts and parasites such as Clonorchis sinesis and ferentiating a diagnosis of obstructive from otherFrom the Departments of Surgery, Swedish and Northwest Hos- types of jaundice by clinical laboratory analyses

pitals and the University of Washington School of Medicine, that are still in use.Seattle.Reprint requests to: Thomas Taylor White, MD, 1221 Madison Obstructive jaundice begins insidiously andStreet (1411), Seattle, WA 98104.

484 JUNE 1982 * 136 * 6

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

steadily worsens without preliminary gastrointes-tinal disturbances. Patients with gallstones may

have had previous attacks of colic or even an

episode of jaundice with the passage of a stone.Some patients with calculi may have painlessjaundice. Most patients with carcinoma of the pan-

creas have back and epigastric pain. Cancer ofthe pancreas is usually preceded by pain and lossof weight and at times accompanied by steator-rhea.

Other possible diagnoses are ampullary or bileduct carcinomas. About a million new cases ofcholelithiasis are discovered in the United Stateseach year, of which about 80,000 (8 percent)have common bile duct stones. There are about25,000 new cases of carinoma of the pancreas

each year, about half of which are accompaniedby jaundice, and 7,000 to 8,000 new cases of bileduct tumors. We are recognizing increasing num-

bers of new cases of jaundice due to parasitic in-festation of the bile ducts in Asian refugees to theUnited States. We are also seeing strictures of thebile duct due to surgical injury at the rate of 1 or

2 per 1,000 operations on the extrahepatic biliarysystem. 1-3

The liver swells considerably when the mainbile ducts are obstructed, with the result that thisenlargement of the liver strongly suggests mechan-ical obstruction rather than hepatitis or drug-in-duced jaundice. A palpably enlarged gallbladdersuggests malignant extrahepatic obstruction ratherthan gallstones.

Physiologic Tests

Jaundice due to conjugated bilirubin is accom-

panied by bilirubinuria. This is due to reflux ofconjugated bilirubin into the circulation usuallydue to obstruction of the bile ducts that, whencomplete, is accompanied by white stools devoidof bilirubin metabolites and characterized by the

disappearance of urobilin from the urine. Refluxcan also be caused by lesions of the liver cells dueto hepatitis or cirrhosis. Liver cells continue toconjugate the bilirubin, but the excretion of con-jugated bilirubin in the bile is diminished.

Serum alkaline phosphatases hydrolyze phos-phoric acid esters in an alkaline medium. Thelevels of serum alkaline phosphatase are expressedin conventional units: their normal concentrationis between 1.5 and 4 Bodansky units (BU), 3 to15 King-Armstrong units or 20 to 85 IU per dl.The serum alkaline phosphatase levels are elevatedin obstructive jaundice and infiltrative lesions ofthe liver. The mechanism of this increase isthought to be an increased production of phos-phatases by the liver cells. One sees a moderateelevation of serum alkaline phosphatase in thecourse of cirrhosis or acute hepatitis. An elevatedalkaline phosphatase level is not specific for liverdiseases as it also occurs in association with lesionsof the bones. The concentrations of the other twoserum enzymes, 5-nucleotidase and leucine amino-peptidase, parallel that of the alkaline phosphatasesin liver disease but their concentrations do notincrease in bone disease. The isoenzymes of phos-phatase can be easily identified by electrophoresisif there is doubt as to their origin.

The liver synthesizes and esterifies most choles-terol but some esterification also takes place in theplasma. The latter esterification depends on thelecithin-cholesterol-acyltransferase synthesized bythe hepatocyte and released into the circulation.The serum concentration of cholesterol usually isbetween 180 and 250 mg per dl, with 40 percentunesterified and 60 percent esterified. The level ofserum cholesterol rises in cases of obstructivejaundice because, as with the serum alkaline phos-phatases, the hepatocyte produces increased quan-tities of this material. An elevated serum choles-terol level is not found in all cases of obstructivejaundice, and it may be elevated in some casesdue to effects of drugs. The proportion of esteri-fied cholesterol diminishes in liver failure.

Transaminases catalyze the transfer of aminegroups to ketoacids. Glutamic-pyruvic transami-nase (GPT), or alanine aminotransferase, andglutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), or as-partate aminotransferase, are present in the serum.The normal values vary from laboratory to labo-ratory depending on method. These enzymes arepresent in an abundance in body tissues. Theliver contains more GPT than GOT but the muscles,particularly those of the heart, contain more GOT.

THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 485

ABBREVIATIONS USED IN TEXT

ACMI=American Cystoscope Makers, Inc.CT=computerized tomographyERCP= endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatographyGOT=glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (now

aspartate aminotransferase)GPT= glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (now alanine

aminotransferaseHIDA=USAN code designation for N-substituted

iminodiacetic acid (Lidofenin)PTC=percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

The transaminases pass in large quantities intothe serum in liver necrosis. Serum GPT levels areinitially more elevated than GOT. The plasmalevels of GOT later will be higher than those ofGPT because of the prolonged survival of GOT.'5

Thus, in cholestasis there is an elevation ofserum concentration of conjugated bilirubin, cho-lesterol and alkaline phosphatase. The pro-thrombin time is prolonged due to reduced ab-sorption of vitamin K, but becomes normal afterparenteral administration of this vitamin.

Imaging TechniquesThe simplest imaging technique for diagnosing

obstructive jaundice is that of taking a plain x-rayfilm of the abdomen. This technique is very usefuldiagnostically when stones can be seen but, unfor-tunately, only 10 percent to 15 percent of gall-stones contain enough calcium to be radiopaque.This approach is also valuable in the unusual in-stance where gas can be seen in the gallbladder orcalcium appears in the wall of the gallbladder. Aplain abdominal film should be made before anyother type of study.6

UltrasonographyDiagnostic ultrasonography uses sound waves

that are reflected from interfaces between tissues,which produces differences in acoustic impedance.At first these instruments were capable of produc-ing only black and white images but now can pro-duce images with eight or more shades of grey(B mode) so that a much clearer picture of ana-tomic and pathologic structures can be obtained.This approach can show sonolucent bile in thegallbladder lumen and a collection of echoes inthe dependent portion of the gallbladder producedby the stones, with acoustic shadows posterior toeach calculus. Using ultrasonography it is possibleto detect more dilated bile ducts and thus we candetermine whether we are dealing with obstructiveor hepatocellular jaundice. Dilatation of the extra-hepatic bile ducts tends to occur in obstructivejaundice before any changes occur in the intra-hepatic ducts and can be presented even beforeabnormalities are seen in liver function tests. Anormal-sized common hepatic duct and the proxi-mal portion of the common bile duct can be de-tected in oblique views anterior to the portal veinin most patients. The distal portion of the commonbile duct can be seen less often. Stones are usuallynot seen in the enlarged distal common bile duct.Enlargement of the head of the pancreas can be

detected, but it is impossible to use this techniqueto differentiate between cancer and pancreatitis.7-'3It must be remembered that normal-sized ductsmay be obstructed and dilated ducts may be un-obstructed (Figures 1 and 2).

Computed TomographyComputerized tomography (CT) is an x-ray

technique wherein differences in tissue densitycan be identified with the use of a computer. The

Figure 1.-Ultrasonography image showing the dilatedcommon bile duct (arrow) adjacent to the portal veinin a patient with carcinoma of the distal bile duct.

Figure 2.-Ultrasonography image showing the dilatedcommon bile duct adjacent to the portal vein (arrow)in the same patient as Figure 1, but from another angle.

486 JUNE 1982 * 136 * 6

.*Awiw.

ki. 1.

4.11. q:..

".k. 416 1%

N.

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

ducts and accumulation in the gallbladder and itsdrainage into the intestine. It is possible to iden-tify the gallbladder and bile ducts even in thepresence of impaired liver function and serumbilirubin concentrations up to 7 to 8 mg per dl.This substance has a relatively short half-life,absence of beta emission and an ideal photon peakso that it can be given safely in high enough dosesto obtain good images in a short time. The tech-

Figure 3.-CT scan image showing dilated hepaticducts in a patient who has had resection of a tumorof the bifurcation of the hepatic ducts.

anatomic definition is much more precise thinwith ultrasonography but the equipment needed tocarry out this type of study is very expensive andaccompanied by considerable irradiation (Figure3). This technique is more effective than ultra-sonography, especially in patients afflicted withmuch intestinal gas and those who are extremelyfat. But the absence of fat in poorly nourishedpatients reduces the quality of the CT image. Bothultrasonography and CT scan play an importantrole in the evaluation of jaundice. Identification ofdilated bile ducts usually, but not always, indicatesthe presence of bile duct obstruction and helpsdistinguish between obstructive and hepatocellularjaundice. Both of these techniques can be carriedout in instances where oral and intravenousmethods of cholangiography are useless. Mostauthorities prefer to use ultrasonography first,using computed tomography when inadequateimages have been obtained by the other tech-nique.'4"5 The fact that a CT scan study costsabout four times that of an ultrasound study isanother point in favor of ultrasonography.

Radionuclide ImagingAn important new tool for functional and

anatomic imaging of the liver and biliary tree,especially in jaundiced patients, has been tech-netium 99m-labeled N-substituted iminodiaceticacid (Lidofenin, or HIDA). This substance israpidly taken up by the liver and excreted in thebile ducts in sufficient concentrations so that thegallbladder and bile ducts can be seen as it ac-cumulates there. One can evaluate the pickup ofthis substance in the liver, excretion by the bile

.:'A....4p

:..f

Figure 4.-Normal HIDA (Lidofenin) scan showing ra-dioactive uptake appearing not only in the biliary tractbut also in the duodenum.

Figure 5.-HIDA (Lidofenin) scan showing an ob-structed distal bile duct and gallbladder with no radio-active uptake seen in the duodenum.

THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 487

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

- _ ' _ S e

Figure 6.-Photograph of a percutaneous cholangio-gram done on the same patient as in Figure 3, showinga dilated left hepatic duct.

nique's greatest value is in the evaluation of acutegallbladder attacks in which an image of the bileducts appears and the gallbladder does not. It is90 percent to 95 percent accurate in detectingacute cholecystitis in this situation. It also is use-ful in determining the presence of obstructivejaundice, wherein the material accumulates in thebiliary tree and does not appear in the intestine,with an accuracy of 30 percent to 50 percent infour hours (Figures 4 and 5). In biliary atresia,it does not appear outside of the liver and a largeimage of the choledochus appears in choledochalcysts.15~-18

Transhepatic CholangiographyPercutaneous transhepatic cholangiography

(I'TC) was first carried out by Huard and Do-Xuan-Hop in 1937. Over the next 35 to 40 yearsit was rarely done because of the frequent com-plications of bile peritonitis, cholangitis and sepsis.Carter and SaypolP9 in 1952 placed a No. 17spinal needle in the hepatic ducts, took x-rayfilms and used this needle as a drain. Ten yearslater, Arner and associates29 were able to use animage intensifier so that even nondilated intra-hepatic ducts in many situations can be seen.A number of other approaches have been de-

veloped since then but a modified procedure thatuses a long thin needle through the entire thicknessof the right lobe of the liver appears to be the mostsuitable for nonsurgical patients and to have theleast complications. Okuda and colleagues2' at theChiba University of Medicine carried out a largescale study using a 23-gauge needle with an outerdiameter of 0.7 mm and a length of 15 cm that

could be inserted into the liver percutaneouslyfrom the right midaxillary line. It was directedfrom the flank toward an area slightly above thejunction of the right and left hepatic ducts with apatient on an image-intensification table, parallelto the table until the tip of the needle is positionedin the hepatic parenchyma to the right of the 12ththoracic vertebra. Contrast material is then in-jected slowly as the needle is withdrawn underimage intensification. Contrast material runs awayquickly when injected into the hepatic or portalveins, but persists in the hepatic ducts, outlines theducts and moves slowly toward the commonhepatic ducts. Insertion of the needle can be re-peated safely several times until the bile ducts areseen. When the bile ducts are identified, enoughcontrast material is injected to fill the biliary treeand take multiple x-ray films (Figure 6).Okuda and co-workers21 in their initial series

were able to examine the ducts of 54 of 80 pa-tients with hepatobiliary problems and nondilatedducts. Sepsis developed in 11 of the 314 patientsstudied and the gallbladder was punctured in onepatient. In studies carried out by Elias and col-leagues,22 cholangitis developed in two patientsand in one a major leak of bile into the peritoneumafter percutaneous cholangiography using thisneedle, both of these patients having marked dila-tation of the biliary system. They were somewhatmore successful in defining extrahepatic ratherthan intrahepatic cholestasis by percutaneous cho-langiography. The group with intrahepatic cho-lestasis could be better defined using endoscopicapproaches. Juler and associates23 used percu-taneous cholangiography in 30 patients with bileduct obstruction. They observed that 40 percenthad bile leakage of 5 to 500 ml at laparotomy orautopsy and nine had peritonitis. They also ob-served that bacteremia developed in 23 percent.This study suggested that PTC with Chiba needlehad little advantage over the larger sheathedneedles and that surgical standby was required insuspected cases of obstructive jaundice. These pa-tients should be given prestudy antibiotic agentssuch as cephalosporins.

Percutaneous DrainageAt this point, several authors24-28 suggested that

intubation of the hepatic ducts using a combina-tion of the percutaneous transhepatic cholangiog-raphy technique and the Seldinger angiographycatheter was satisfactory and the complicationswere few. A PTC using a 23-gauge needle was

488 JUNE 1982 * 136 * 6

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

carried out first. The needle was removed and an18-cm long needle with an overlying thin-wallpolyethylene catheter was installed, either in thesame direction into one of the right intrahepaticduct branches or using a frontal approach underfluoroscopic control into one of the intrahepaticbile ducts of the left lobe of the liver. After bilewas obtained, the needle was withdrawn and thesheath catheter was left in place through which aguide wire was inserted and positioned in one ofthe larger bile ducts at a suitable distance from itsentry into the ductal system. The catheter wasthen withdrawn and a Seldinger catheter with sev-eral side holes at the tip, such as a Kifa Greencatheter 1.2 mm in inner diameter, was introducedover the guide wire. The guide wire was thenwithdrawn and the catheter advanced farther downinto the common hepatic duct.A very large number of patients have now been

reported on who had PTC of this nature with sub-sequent external bile drainage through tubes. Thistechnique allows recovery of liver function andimprovement in a patient's general condition be-fore radical or palliative surgical intervention andnonsurgical palliation in advanced cases of ma-lignancy; it also prevents postcholangiographyleakage from the liver. In a series from Lund,Sweden,25 emergency operation because of bileleakage despite established drainage of the bileducts was necessary in only 3 out of 105 patients.In a series from Philadelphia,24 the biliary treewas successfully catheterized in 41 of 43 cases ofobstructive jaundice. Both of the failures could betraced to extensive occlusion of the intrahepaticductal system by tumor. Once drainage was es-tablished, 22 of 39 patients had considerable re-ductions in total serum bilirubin at the rate of 2mg per dl a day, with improvement in symptoms.Mean total serum bilirubin level dropped from19.9 to 4.7 mg per dl. The major complication ofpercutaneous transhepatic catheterization was exa-cerbation of a preexisting infection with bactere-mia in the obstructed ductal system despite anti-biotic coverage after a "golden" period of three tofive days.

Recent studies published by Ferrucci and col-leagues29 from the Massachusetts General Hos-pital advocate a variation of the techniques origin-ally described by Hoevels, Ring, Nakayama andtheir associates.°0 They point out that guidewires of adequate caliber to support catheter ex-changes will not fit the Chiba needle. For thisreason, standard fine needle puncture should be

followed by puncture with a special 15-cm 18-gauge sheathed cannula in a separate step. Theseauthors have found the biliary catheter especiallydesigned by Ring and co-workers,30 a 40-cm long8.3 French multiple-side-hole catheter with atapered tip and a pigtail terminus, is most suitablefor introducing into the distal duct or all the wayinto the duodenum. Complications occurred in 15out of 62 patients, of which three were major.Other complications included one case of delayedsubphrenic abscess and two cases of bleeding.The complications of catheter occlusion, bleed-ing through the catheter, unrelieved jaundice andsepsis due to dislodgement of the catheter havebeen discussed at some length.A recent study3l showed a 29 percent operative

mortality in 148 severely jaundiced patients under-going operation without prior decompression, incontrast to an 8 percent operative mortality in69 patients undergoing preoperative transhepaticdrainage. Further refinement of the above tech-nique has made it possible to manipulate percu-taneous transhepatic catheters through an ob-structing lesion into the distal segment of the bileduct or the duodenum24 to facilitate combined ex-ternal bile drainage.

Based on this experience with temporary cath-eters, a nonsurgical technique of introducing apermanent Teflon bile duct endoprosthesis hasbeen developed25'26 This endoprosthesis is insertedfollowing percutaneous transhepatic puncture andinsertion of catheters into the bile duct system andcan be left in place for long periods. They can bereplaced if obstructed, displaced or compromisedby cholangitis, all frequently occurring complica-tions. It appears that nonsurgical insertion of abile duct endoprosthesis may be the only palliativeprocedure in situations where there is a cytologic-ally verified malignant tumor obstructing the ex-trahepatic bile ducts.2 It is probably best suitedfor elderly patients with poor general condition,those with generalized malignant disease, thosewith metastatic tumor obstructing the bile ductsand those patients in whom a surgical procedurewould be impossible for technical reasons.

Endoscopic RetrogradeCholangiopancreatogrvphy

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatog-raphy (ERCP) was first described in 1968 by Mc-Cune and colleagues32 but did not become widelyavailable until a year later when Oi and associates,"using a new duodenoscope, were able to cannu-

THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 489

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

late the papilla of Vater with greater ease using aright-angle viewer rather than a straight-aheadinstrument. A cannula is introduced from below,rather than above as in percutaneous cholangiog-raphy, for injection of radiopaque medium (Fig-

..

Figure 7.-Drawing showing the technique of endo-scopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)from T. T. White and F. Silverstein (Cancer 1976 Jan;37:449-461).

Figure 8.-Photograph taken during endoscopic retro-grade cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showing sev-eral stones in the distal bile duct.

ures 7 and 8). This is primarily an imaging pro-cedure for obtaining good x-ray studies of thebiliary system.

Sepsis and pancreatitis are the two main hazardsof retrograde injection, chiefly because of the in-creased pressure with injection.34'85 Pancreatitiswith some degree of elevation of serum amylaselevel occurs in most patients in whom the pan-creas is opacified, especially when overopacifica-tion of the acini occurs. Sepsis occurs primarilyin patients with poor drainage of the biliary tree.Many of the patients with stasis were alreadyinfected before the injection, with sepsis and cho-langitis occurring because of dissemination of bac-teria into the circulation as a result of the injec-tion.36 When there is poor drainage of the biliarytree, injection of contrast medium should be keptto a minimum with the aim of reducing the riskof cholangitis. Otherwise, injection should con-tinue until the biliary tree and gallbladder arefilled. Tilting the patient helps to fill the hepatictree. A number of pictures should be taken be-cause the radiopaque medium tends to layer,which produces distortion. Calculi float up theduct. Sclerosing cholangitis, strictures, carcinomaof the bile ducts and compression of the distal bileduct by carcinoma of the pancreas or chronicpancreatitis can be seen in the cholangiograms. Itmay be possible to diagnose lesions high in thebiliary system by inserting a brush into the biliarytree by this route to obtain specimens for cyto-logic examination. Cancers of the lower bile ductor papilla are easily diagnosed by visual examina-tion at endoscopy and easily confirmed by ex-amination of cytology or biopsy specimens.37'38

This is an excellent approach for differentiatingobstructive from hepatocellular jaundice and forobserving both jaundiced and nonjaundiced pa-tients after biliary surgical procedure for stricture,stone or normality. Evidence obtained in thismanner can serve as a guide to the treatment of anobstructed bile duct, whether by surgical or en-doscopic papillotomy, surgical drainage, othertypes of drainage procedures or medical therapy.38A good review article on this subject was writtenin 1977 by Cotton.36

Cephaloridine, cefazolin sodium, and gentami-cin sulfate are useful prophylactic agents whengiven in conjunction with these procedures. Re-tained dye in the biliary tract or pancreas shouldbe drained immediately.

490 JUNE 1982 * 136 * 6

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

Endoscopic SphincterotomyRetained and recurrent common bile duct

stones through the years have required surgicaltreatment. Endoscopic sphincterotomy is an ex-tension of ERCP first described in 1974 by Kawaiand co-workers39 and Classen and Demling,40 andseveral thousand such procedures have since beencarried out.41-43 The key to doing this procedureis the use of a right-angle fiberduodenoscope suchas is used for ERCP through which a sphinctero-tome, consisting of a wire drawn through thecatheter used for papillary cannulation, is insertedinto the papilla (Figure 9). The distal end of thewire is fixed to the tip of the catheter so that whenit is pulled, the tip of the catheter bends so thata segment of the wire separates from the catheter,producing a sawlike wire that can be used as acautery. A mixed cutting and coagulating currentis used for sphincterotomy.

The first step of the procedure is selective retro-grade cannulation of the biliary tract and injectionof radiopaque medium for x-ray studies. Afterobserving the ampulla and clarifying the anatomyof the biliary system, one advances the sphinctero.tome into the bile duct, establishing its position byfluoroscopy. The sphincterotome is then drawnback under visual control until the proximal endof the free portion of the wire is just outside thepapilla. The direction of incision should then beupwards at the 10 or 11 o'clock position whenfacing the papilla. The average length of the in-cision in the bile duct should be 17 mm.Common bile duct stones are removed with a

Dormia basket catheter. The closed catheter isadvanced beyond the calculi under fluoroscopiccontrol, then the basket is opened and an attemptmade to capture the stone and remove it from thebile duct. A captured stone can be pulled out ofthe duodenum along with the endoscope. Theoverall success rate of this technique is reportedto be between 90 percent and 95 percent.

The main complications have been bleeding,retroperitoneal perforation, pancreatitis, cholangi-tis with an impacted stone and an impactedDormia basket, with the total incidence of com-plications occurring in less than 7 percent ofoperations done. Emergency laparotomy has beenrequired in somewhat less than 2 percent and theoverall mortality of this procedure is less than 1percent.

Endoscopic sphincterotomy was initially usedonly for postcholecystectomy patients who were

elderly, poor risks or in whom there were tech-nical problems. At present, high risk patients whostill have their gallbladder and in whom acuteobstructive cholangitis or obstructive jaundice canbe relieved before cholecystectomy are beingdrained in this fashion. This converts a high riskpatient to one who is a candidate for an electivecholecystectomy, with well-defined biliary anatomyshowing residual stones that can be flushed out.This technique, however, should be carried outonly in the hands of skilled endoscopists.41-44

CholedochoscopyCholedochoscopy has gradually developed since

Bakes designed a speculum in 1923 for examin-ing the interior of the bile ducts at operation. Heused an instrument somewhat like the ones usedto examine the vocal cords today. Later attemptswere made in the 1930's to look at the interiorof the gallbladder using a cystoscope. The firstcholedochoscope was described by McIver in194145 and manufactured by the American Cys-

Figure 9.-Photograph taken during retrograde cholan-giopancreatography showing endoscopic cannulation ofthe distal bile duct with the cutting wires in place forendoscopic sphincterotomy in the same patient as inFigure 8. The stones shown in Figure 8 were latersuccessfully removed.

THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 491

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

toscope Makers, Inc. (ACMI). This had a ratherdim light with the intraductal portion of the in-strument at right angles to the viewing arm. An-other choledochoscope described by Wildegansand manufactured by Wolf had a 60-degree ratherthan a 90-degree angle. The most recent choledo-choscope of this type was introduced by Storz-using the Hopkins rod lens optical system, whichgives a more effective optical function and uses afiberopticlike carrier to furnish light. This rigidright-angle choledochoscope measures 3 mm indiameter and is 4 or 6 mm in length, dependingon the model. An instrument guide channel canbe attached for the passage of stone-retrieval in-struments or biopsy forceps.The first flexible fiberoptic choledochoscope

was introduced by ACMI in 1965,4 with an opticalperformance somewhat inferior to that of the rigidscopes previously introduced. More recently, sev-eral new models of flexible instruments with direc-table tips have been introduced by OlympusOptical Co., Fuji, Machida and ACMI4' that canbe used both at operation and through a T-tubetract. These instruments have been greatly im-proved over the early ACMI scope.

i

: \

\.

ir 1

I.e

.I

*

Figure 10.-Illustration of one of the several types ofavailable flexible endoscopes for examining the interiorof the bile duct. This particular one was manufacturedby American Cystoscope Makers, Inc. (ACMI).

Techniques that not only locate gallstones inthe common and hepatic ducts but also reliablyensure that no stones have been left behind areessential in the treatment of benign and malig-nant obstructive jaundice. Intravenous cholangiog-raphy, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiographyand ERCP have been used for these proceduresand for operative cholangiography.48-50 The bileduct is explored when cholangiograms show thepresence of filling defects or bile duct obstruction.The common bile duct has been blindly exploredfor years with a number of different types offorceps and probes that also gauge the diameterof the ampulla by feel. These instruments caneasily extract a stone from the duct. Flushing hasbeen used to help remove stones. One cannotpalpate extremely small stones. The rigid choledo-choscopes manufactured by Storz and Wolf havethe advantage of good optics and good light, to-gether with ease of use in determining visuallywhether or not further sludge, stones or calculiremain in the bile duct after instrumental re-moval. They also are useful in taking biopsy speci-mens from the interior of the ducts in cases ofsuspected malignancy. They cannot, however,reach far up into the hepatic ducts in search ofstones and cannot be used during the postopera-tive period through a T-tube tract. The flexiblecholedochoscopes vary from 5 mm (ACMI) to 6or 7 mm (Olympus, Fuji and Machida) and canbe passed down a T-tube tract following T-tubedrainage of the common duct.The operative Olympus CHF-B3 flexible cho-

ledochoscope, which has appeared recently, is aconsiderable improvement over the earlier flexiblescopes but it is difficult to advance down the duct,as are the instruments made by ACMI, Fuji andMachida. All four types of instruments havegraded amounts of flexibility and directabletips.47 51 This type of instrument appears to bemuch more useful for looking high up into theliver and into the bile ducts through a T-tubetract during the postoperative period followingcommon bile duct exploration,47'5253 than forroutine choledochoscopy at operation where thebulk of the stones are between the bifurcation ofthe hepatic ducts and the ampulla (Figure 10).

The fiberoptic flexible scopes cost from $4,000(ACMI) to $6,000 to $7,500 each (Olympus, Fuji,Machida). The rigid choledochoscopes cost$1,500 to $2,000 each. These instruments can beused only once every 24 to 72 hours because ofthe nced for gas sterilization and aeration.

492 JUNE 1982 * 136 * 6

II

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

Obstructive Jaundice Due to GallstonesGallstone disease is thought to occur in about

10 percent of the adult population in the UnitedStates and in about 20 percent of people over theage of 40. The incidence of cholelithiasis in-creases progressively with aging. Thus, gallstonedisease is one of our most common illnesses, withabout 500,000 cholecystectomies carried outyearly for this disease. The most common seriousproblem of gallstone disease is that of calculi inthe extrahepatic biliary ducts causing obstructivejaundice and its complications. The overall inci-dence of bile duct calculi in patients undergoingcholecystectomy ranges from 7 percent to 15 per-cent in different series, so that approximately oneout of ten patients with gallstone disease hascholedocholithiasis at the time of the primarybiliary operation. The treatment of obstructivebiliary disease with or without cholangitis orjaundice has been simplified by the addition ofultrasonography and HIDA and CT scans, ERCPand percutaneous cholangiography, which providea clearer definition of the problems faced byclinicians and surgeons. The routine managementof stone-related jaundice still involves cholecys-tectomy, cholangiography, common duct explora-tion with removal of stones and drainage of thebiliary tree.

Measurements of intrabiliary pressure duringoperation or manometric cholangiography havebeen carried out in Europe for years but haveonly recently been added to the armamentarium

of American surgeons.54'55 These techniques showsmall obstructions to outflow of the biliary systemwhereas x-ray studies show layer deformities andfilling defects caused by the presence of stones.56'57Flow and pressure studies are easy to do and areuseful in making a diagnosis of pathology of thedistal bile duct, but still need to be standardized.The various types of choledochoscopes de-

scribed above have all been developed in the lastten years and are useful for locating stones in theduct system not ordinarily found by the blindtechniques used in the past. The rigid choledo-choscopes are useful for more routine cases wherethe stones are in the common hepatic and commonbile ducts. The flexible types made by ACMI,Olympus and others are especially valuable foridentification of stones in more remote areas ofthe biliary systems, such as high in the liver.47-53A useful adjunct in the postoperative period

has been the possibility of removing stonesthrough a T-tube tract that have been misseddespite careful exploration. Cholic acid58 and,more recently, Capmul (a solvent manufacturedby Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. and currently underinvestigation) have been introduced in an effortto dissolve cholesterol stones that have beenleft behind after common duct exploration. Also,simple irrigation of the T tube with saline orheparin will dislodge many of these stones intothe duodenum. At the same time, as these newsolutions have emerged it has become possibleto pass steerable catheters down into the common

- ;- r'. 72- .- 3zc " - "ter3-eler r' r-eIe .rCDe-rtcn a_rtj r-enc r fe reerj' - r r p'

Figure 11.-Diagrammatic representation of removing stones by a directable stone basket (from White and Harrison2).

THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 493

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

bile duct under fluoroscopic guidance so thatstones can be trapped with a Dormia basket andpulled out through a T-tube tract to the surface(Figure 11). This technique requires that the Ttube left in the common bile duct following ex-ploration be large enough to allow passage ofinstruments to the bile duct. At first this was doneby putting a large catheter over the outside of thevertical arm of the T tube.59,60 T tubes are nowavailable in which the vertical arm is four sizeslarger than the part inserted into the duct, allow-ing a relatively small tube to be placed in the ductwith a larger branch extending to the surface. Apart of this technique requires that the verticalarm be run laterally so that with a patient in asupine position a radiologist can see the instru-ment passing through the tract without overlap-ping the bile duct. With this approach one mustwait six to eight weeks after the operative pro-cedure to allow formation of a solid tract thatwill not be damaged by instruments.At the same time that this technique was being

developed, surgeons, internists and radiologistsdiscovered that a fiberoptic bronchoscope couldbe passed down through a T-tube tract into thecommon bile duct for extraction of stones. Thespecial choledochoscopes described above areuseful for extracting stones under direct vision inthe postoperative period.5' At present, it appearsthat the mechanical methods of extraction ofstones in the postoperative period are more effici-ent than those of chemical dissolution.

The nonoperative approaches to decompressionin patients with advanced obstructive jaundice,cholangitis or both constitute additional spectacu-lar advances in the past ten years.233' Percutane-ous drainage of the biliary tree and endoscopicsphincterotomy and drainage of this system haveprogressed to the point that this approach is avail-able in a great many major centers of the UnitedStates by physicians faced with the emergencytreatment of a severely debilitated patient withoverwhelming jaundice and sepsis. Definitiveoperative procedures can be carried out when apatient is in reasonably good general condition.

Less severely ill patients are treated as before.We have the alternative, however, of doing endo-scopic sphincterotomy and drainage of the biliarytree postoperatively and in unoperated patientswho do not have a T tube in place, as well as inthose with stones that cannot be extracted througha T-tube tract. The approach used should bedictated by the availability of experts in the use

of these techniques. Standard techniques of cho-lecystectomy or drainage of the common bileducts should be used whenever the newer tech-niques are not available. Whichever method isused, emergency drainage of the common bile ductfor septic cholangitis should always be carriedout. Orloff"' reports that "the exact incidence ofretained and recurrent bile duct stones is notknown because most patients who undergo cho-lecystectomy with or without choledocholithotomyare rapidly restored to good health. There havebeen no thorough long-term postoperative studieson selected patients with gallstone disease. Mostof the available data on the incidence of residualstones has been obtained during the early post-operative period and most of it has been based oncholangiography performed through a T tube inthe common bile duct within two weeks of opera-tion. "61(p404)

The rate of retained calculi following a com-mon bile duct exploration has been consistent,ranging from 10 percent to 13 percent of patients,while that following negative findings at choledo-chotomy has been substantially lower. Becausethese observations have been confined to the im-mediate postoperative period, the true incidenceof retained and recurrent bile duct stones is un-doubtedly higher. The incidence of residual cho-ledocholithiasis following cholecystectomy withoutcommon bile duct exploration is unknown, but itappears to be quite low. Thus, there continues tobe a prevalence of residual common bile ductstones found from several days to several yearsafter the initial operative procedure despite morethan adequate critical experience throughout theworld pertaining to the removal of common bilestones. Most of these stones have been thoughtto be retained. For this reason, efforts should bemade to discover the actual incidence of retainedstones by carrying out cholangiography, manom-etry, choledochoscopy and other procedures. Theincidence of secondary operations at various in-stitutions varies from 2 percent to 7 percent, thegreatest incidence being for retained and commonbile duct stones and strictures, followed closelyby cancer and pancreatitis.

Biliary obstruction due to either benign ormalignant disease has been relieved by four majorapproaches, cholecystenterostomy, choledochoen-terostomy, dilatation of the sphincter of Oddi andtransduodenal sphincteroplasty. The gallbladderhas been used as a drainage route for over 100years. A recent study carried out by Dayton and

494 JUNE 1982 * 136 * 6

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

colleagues';2 showed that cholecystenterostomyfailed in 5 out of 59 cases of malignancy and 4out of 17 of benign disease for an overall failurerate of 12 percent. Our own studies suggest aneven higher failure rate of nearly 20 percent.

Bakes' hoped that ampullary dilatation using aseries of dilators bearing his name would allowany retained stones to pass after exploration of thecommon bile duct. Whereas early studies indicatedthat dilatation practically eliminated the possibilityof residual stones, later authors such as Jones andSmith,'; Kune and Sali5 and Heimbach and White';4have noted the ineffectiveness of dilatation in pre-venting retained and recurrent stones and havefelt that transduodenal sphincteroplasty of cho-ledochoduodenostomy were preferable to dilata-tion of the sphincter. Lateral choledochoduode-nostomy has been reported by Rodney Smith65 toresult in a sump syndrome in over half of 250cases reported on by another London surgeon. Hehas carried out transduodenal sphincteroplasty onthose patients, with considerable long-term suc-cess. Kune and Sali5 and this author have notedsimilar problems and solved them in the same way.These and other procedures on the biliary tracthave never really been studied in a prospectivefashion. It appears now, however, that it may bepossible to eliminate most of the retained andresidual stones appearing in the late postoperativeperiod using endoscopic sphincterotomy. This ap-proach has been used with increasing frequency,with the result that some recent publications sug-gest that endoscopic sphincterotomy is the pro-cedure of choice for retained and residualstones.41-44

Strictures of the ampulla of Vater and the lowerend of the common bile duct are usually sequelaeof the passage of multiple stones from the biliarysystem into the intestine. Such strictures can bethe cause of primary common bile duct stoneswith secondary jaundice, dilatation and cholangitisand may occur both primarily and after commonduct exploration. Stenosis of the sphincter of Oddihas been described in two different ways, onesuggesting that actual fibrosis of the sphincter hasoccurred and the other that there is inflammationof the sphincter and spasm.

The diagnosis is made frequently in Europeand South America and much less frequently inNorth America.2 There is considerable ambiguityas to what this condition actually consists of.Names such as ampullary fibrosis, distal stricture,fibrosis of the sphincter, vaterian segment obstruc-

tion, phimosis of the ampulla, chronic odditis andchronic papillitis have been used. Patients with thissyndrome usually have a common bile duct morethan 15 mm in diameter and intermittently mayhave elevated serum bilirubin or serum alkalinephosphatase levels or both, especially after theinjection of a stimulus to bile secretion such assecretin. The ducts are found to be dilated onultrasound studies and percutaneous cholangio-grams, the ampulla can be cannulated only withdifficulty on ERCP and there are common bile ductstones present in about half of the cases. Patientswith spasm or dyskinesia, however, have a normalduct size with easy cannulation by ERCP and with-out jaundice, chemical abnormality or stones inthe bile duct. Attempts have been made in recentyears to measure sphincteric pressure using bal-loons or perfusion with saline during ERCP can-nulation. It is not clear as yet what the besttreatment of spasm or dyskinesia is and whether itis necessary to go as far as in the treatment ofpapillary stricture and stenosis.

Cases of clear-cut stenosis or stricture of thebile duct are now usually evaluated preoperativelyby percutaneous cholangiography or ERCP. Mano-metric cholangiography can be carried out intra-operatively and will show intrabiliary pressure ofover 20 cm of water, low flow and obstruction inthe distal bile duct. It will also be difficult or im-possible to pass a No. 3 Bake's dilator through thesphincter. There has been considerable discussionas to whether these secondary patients are besttreated by choledochoduodenostomy, transduo-denal sphincteroplasty or endoscopic sphincterot-omy. Most patients are being treated with oneor the other of the two former procedures, withsome physicians advocating endoscopic sphinc-terotomy for more debilitated patients.43'44

If an operative procedure is to be carried out,there are certain special considerations that causeone to choose a sphincteroplasty rather than acholedochoduodenostomy (Figure 12).6366 67 Apatient found at exploration to have not only astricture of the ampulla but also coexistent pan-creatitis that is not constricting the intrapancre-atic portion of the bile duct should have a sphinc-teroplasty with division of the pancreatic ductsphincters.A patient with substantial narrowing of the

intrapancreatic bile duct should have a choledo-choduodenostomy because the sphincteroplastywould in this situation be below the point ofbiliary obstruction. Sphincteroplasty is preferable

THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 495

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

/

I _

Figure 12.-Artist's drawing of a technique of choledo-choduodenostomy.

.~~~~~~e C , Litt.t,; ,,

Figure 13.-Papillotomy is a quicker method of remov-ing small stones. An incision of about 2.5 cm is re-quired to cut the entire sphincter mechanism.

when the duodenum must be explored because ofsuspicion of some form of intraduodenal malig-nancy or because a stone is impacted in the distalend of the bile duct and cannot be retrievedotherwise (Figure 13). It is also the preferred pro-cedure when there is associated pancreatitis with-out compression of the distal duct. A choledocho-duodenostomy is preferable whenever the distalintrapancreatic bile duct is narrowed. We preferto do a sphincteroplasty when the duct is less than15 mm in diameter, a choledochoduodenostomyor sphincteroplasty when it is between 16 and 25mm in diameter and a choledochoduodenostomyin larger ducts.869A sphincteroplasty must be long enough to

make the opening between the bile duct and theduodenum roughly the same as the largest diam-eter of the bile duct above. Under these circum-stances one of these operations is preferred tocholedochojejunostomy, because of the metabolicconsequences of placing the anastomosis lower.

This approach is valuable, however, for stricture.The most catastrophic complication of a

straightforward cholecystectomy is that of acci-dental ligature of or injury to the common orhepatic bile duct. This usually preventable tech-nical error is fairly rare, having occurred in 336of 63,252 cholecystectomies done in 1973 in thestate of Ohio.70 This diagnosis should be madeduring or immediately after the operation but theremay be no jaundice or biliary fistula and severalweeks and, uncommonly, several months oryears may go by before stenosis develops to thepoint that stricture or jaundice occurs and reopera-tion is required. Most such injuries are evidentearly by the presence of a bile fistula with ac-companying jaundice, rather than jaundice alone,so that most repairs can be done during the firstfour to six weeks after the initial procedure. Apatient who is reexplored during the first four tosix weeks is often debilitated because of cholangi-tis and occasionally abscess formation. Underthese circumstances, the biliary tract should bedecompressed with catheters or a T tube and thedefinitive repairs postponed until infection andjaundice have subsided.

Only in rare instances where there is redundantduct that allows an end-to-end anastomosis shoulda biliary anastomosis be carried out. Longmire68reported that 11 of his 22 end-to-end anastomosesfailed. The preferred approach, therefore, appearsto be to anastomose the damaged bile duct to aRoux-en-Y jejunal loop both early and late (Fig-ure 14). The anastomosis is made with eitherend of the bile duct to the side of the jejunum orend to end, most surgeons preferring the former.This is relatively simple when the bile duct pro-jects sufficiently below the liver so that a goodextrahepatic anastomosis can be carried out.

The anastomosis is drained internally andsplinted by means of a T tube placed through thebile duct where there is enough bile duct availablebelow the bifurcation. If the suture line is closerto the junction of the right and left hepatic ducts,the upper portion of the tube can be split. Alter-natively, transhepatic tubes can be placed throughboth the right and left hepatic ducts where theproximal portion of the tube has been brought outthrough the liver parenchyma and out through theabdominal wall, as described by Cameron andco-workers,-' Praderi, Saypol and Kurian73 andSmith.74 These approaches have worked best whena very large tube ( I cm in diameter) was passedthrough the damaged or strictured area but have

496 JUNE 1982 * 136 * 6

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

Figure 14.-Artist's drawing showing technique of choledochojejunostomy for decompression of bile duct stricturesin which the damaged bile duct is anastomosed to a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop. (Reproduced with permission fromWhite and Harrison.4)

/@- 5f \ Hes3-: .z.e-.W. .e z;W:+ # \

N _ R w A _ ^N t tw';..... :V 't,S

e,.

,.1 / ,

;t

\s':x- ' '} "f< \ s tv rJ -a .' -.=

z /, :

, 8 i Z

f fot^ L _ffi > : F ^. t i s

Figure 15.-The Longmire operation for high bile ductstrictures. (Reproduced with permission from Whiteand Harrison.4)

the disadvantage of requiring daily injections toflush out debris. Further, they are often compli-cated by cholangitis and bleeding.

Another approach suggested by Longmire 8 isof Roux-en-Y anastomosis of one of the lateralintrahepatic ducts to a jejunal limb after a lateralsegment of liver has been resected (Figure 15).We prefer removing either the entire central por-tion of the liver and then making an anastomosisto the several hepatic branches (Figure 16),X7 orusing the technique devised by Bismuth andCorlette7; of removing a portion of the liver to

Figure 16.-Technique of central hepatic resection forbifurcation tumors and strictures. (Reproduced withpermission from Hart and White."')

expose the main hepatic ducts away from the

hilus, then making the anastomosis.

Cholangitis and SepsisHuman bile is normally sterile but has been

found to be contaminated in most patients withobstructive jaundice, common duct stones withoutjaundice, acute cholecystitis and patients over 60years of age regardless of the type of pathologic

THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 497

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

condition found.77 Positive bile cultures are foundat an increasing rate with advancing age evenwhen only uncomplicated gallstones are present,with the result that 33 percent of patients over 70have positive bile cultures.78 There appears to begeneral agreement that patients with obstructivejaundice or anyone undergoing manipulation ofthe bile ducts, whether by common bile duct ex-ploration, percutaneous cholangiography or ERCP,should have prophylactic antibiotic therapy. Ceph-aloridine given just before the procedure has beenproved effective in reducing wound sepsis andsepticemia.79 Other effective regimens have beendescribed using cefazolin80'81 and gentamicin.82 Asingle-dose regimen seems adequate in routinecases, rather than the three doses originally pro-posed by Polk and Lopez-Mayor,83 but shouldobviously be continued for a long course in septicpatients.

Sclerosing CholangitisAnother type of obstructive jaundice that is

confused with both primary biliary cirrhosis andcarcinoma of the hepatic ducts is sclerosing cho-langitis. This is an uncommon disease character-ized by obliterative inflammatory fibrosis of theextrahepatic ducts, with or without involvementof intrahepatic ducts.84'85 Patients with the follow-ing conditions are eliminated from this classifica-tion: jaundice due to drug or viral hepatitis, pro-gressive obstructive jaundice, common duct stones,prior bile duct surgery or malignancy. All of thesepatients have thickening and fibrosis of the extra-hepatic and sometimes the intrahepatic bile ducts.Most patients are between ages 30 and 50. Mostpatients are men, rather than women, as seen inprimary biliary cirrhosis.

Tests of antimitochondrial antibody will showlow antibody levels with sclerosing cholangitis,unlike levels found with primary biliary cirrhosis.Diagnosis has been made chiefly at surgical pro-cedures in the past86'87 but now can be readilymade by either ERCP or transhepatic cholangiog-raphy.88 The association of this disease with in-flammatory bowel disease was reported by Warrenand associates89 and is increasingly reported to beso, with 54 percent of Wiesner and LaRusso'spatients and 75 percent of Chapman and co-work-ers'90 patients having associated inflammatorybowel disease.

Elevated serum copper levels are also reportedwith this disease, the role of which is unknown.91Jaundice and pruritus can be alleviated with the

use of cholestyramine resin, which binds with bileand prevents its recirculation, and with cortico-steroids.92 Drainage by choledochoenterostomy orT tube is effective if appropriately established. Ithas been suggested recently (S. I. Schwartz, MD,oral communication, May 21, 1981) that per-cutaneous transhepatic drainage of the biliary sys-tem combined with the administration of corti-costeroid, antibiotic and immunosuppressant drugsmight be quite successful in treating these patients.It has also been suggested that colectomy might beof benefit in the treatment of sclerosing cholangitisin patients with associated inflammatory boweldisease, but the number of patients this has beendone on is small. Dickson and associates93 havesuggested that penicillamine might be effective.Most authors now think that this condition is

an autoimmune reaction in the wall of the bileduct, rather than a bacterial or viral infectiousdisease. Association with retroperitoneal fibrosis,Riedel's thyroiditis, ulcerative colitis and regionalileitis suggest that this may indeed be the cause ofthe process. Positive diagnosis unfortunately re-quires a full-thickness biopsy specimen of thebile duct wall. Again unfortunately, most patientswho have been observed for long periods die, butthis may have been due to the fact that in the pastonly those in advanced stages of the disease wereseen. Earlier cases are now being found by ERCPand percutaneous cholangiography.

Cancers of the Extrahepatic Bile Ducts andHead of the Pancreas

Cancers of the extrahepatic bile ducts occurrelatively infrequently, consisting of less than 1percent of all carcinomas and about 3 percent ofgastrointestinal malignancies. A special handicapto the study of biliary cancer has been the failureof the International Classification of Diseases todistinguish between cancers of the liver and biliarysystem until the seventh revision in 1958. Sincethen about 4,500 deaths from cancers of thebiliary tree have been reported yearly in theUnited States, as contrasted with 18,000 frompancreatic cancer. It appears that the incidence ofbiliary tract cancer is much higher among someracial groups than others, with Japanese havingabout five times the incidence of Caucasians.94'95The true epidemiologic makeup of this diseasestill remains to be clarified.

These tumors have been grouped anatomicallyinto the following three groups according to therelative difference in prognosis of the lesions:

498 JUNE 1982 * 136 * 6

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

group 1, the upper region, including the left andright hepatic ducts and the confluence of the com-mon hepatic duct; group 2, the common bile ductand the region of the cystic duct down to thepancreas; and group 3, the intrapancreatic portionof the common bile duct, including tumors of theampulla of Vater.90Group 3 carcinomas of the distal bile duct and

pancreas may arise from the ampulla of Vater orduodenal epithelium. They may appear grossly asa polypoid growth replacing the ampulla or as anulcer involving the same area. It is this groupabout which the most is known from the point ofview of prognosis and treatment. They have oftenbeen grouped with carcinomas of the head of thepancreas. While they were originally treated bylocal resection and reimplantation into the duo-denum, pancreaticoduodenectomy was first recom-mended for this lesion by Whipple and co-workers97 in 1935 as a two-stage procedure. Atpresent it is usually carried out in one stage,sometimes preceded by endoscopic sphincterotomyor by percutaneous drainage of the liver.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is not an indicatedtreatment for the tumor in patients with metastasesto the liver or regional lymph nodes. The mortal-ity from this procedure has been as high as 50percent as recently as ten years ago but showssigns of falling to about 10 percent in the handsof groups carrying out fairly large numbers ofthese procedures. Long-term survival over fiveyears has been observed in around 35 percent ofpatients undergoing resection, which is the bestoutlook for survival of the various biliary tractcancers. In cases with long-term survival enoughsteatorrhea usually develops to require pancreatinsupplements. Marginal ulcers at the site of gas-tric resection have developed in a number of pa-tients and diabetes is an occasional complication.

Cases of group 2 and 3 carcinomas involvingthe area above the pancreas present different diag-nostic and technical problems from those of theperiampullary area. These have been confusedwith cases of gallstone disease and sclerosingcholangitis in the past, before the advent of ultra-sonography, ERCP and percutaneous cholangiog-raphy.

Malignant tumors of the extrahepatic biliarytree have been noted in the past for late diagnosisin which radical cure was the exception and theprognosis was very bad. A series of 77 patientsreported by Warren and colleagues98 showed thatonly a third (24) had a radical procedure, 17

patients survived for more than a year and fivewere alive after three years. A disappointinglylow survival rate has been reported in severalother series.95'99-102 Information has been scant asto the overall resectability, but some authors havereported that only a tenth to a quarter of patientsare resectable at the time of laparotomy.

Jaundice has been the most important symptomof bile duct tumor and occurs quite early. Thetumors are generally quite small because the lumenof the bile duct is relatively small to begin with.Other symptoms of bile duct cancer are insignifi-cant compared with those of jaundice. Patientsalso have right upper quadrant abdominal painand sometimes colic. The average duration ofsymptoms is two to three months. Physical ex-amination will show an enlarged firm liver with alarge gallbladder when the tumor is distal to thecystic duct or obstructing the cystic duct, causinghydrops of the gallbladder rather than Courvoisier-Terrier syndrome. Laboratory examination willshow extrahepatic ductal obstruction. Ultrasonog-raphy shows dilated common hepatic and intra-hepatic ducts. Both percutaneous cholangiographyand retrograde cannulation of the ampulla of Vaterwill show the location of the tumor.

Particular attention was directed to tumors ofthe bifurcation of the hepatic duct by Klatskin in1965.103 At that time he reported 13 cases ofadenocarcinoma of the hepatic duct, with ad-vanced liver failure terminating in coma as theimmediate cause of death, and he pointed out thathepatobiliary infection was the major factor in thedeaths of most of these patients. He also notedthat only 5 of the 13 patients had clinical evidenceof metastasis at the time the diagnosis of carci-noma was made. He also pointed out that patientswhose livers were decompressed lived an averageof 23.3 months, as opposed to 9.9 months whenthe liver was not decompressed. Some authorshave emphasized that these tumors should be by-passed or excised to prevent cholangitis,104 andother publications have appeared describingmethods of palliation or resection, including com-plete excision with end-to-end anastomosis andreconstruction of the biliary tree.'05The most common type of palliation in the past

has been dilatation of the lesion with probes andsplinting over a T tube, with resection being pos-sible in only a relatively small number of patients,though major hepatic resection was possible insome patients.'06"107 The problem with this ap-proach was that the T tubes became occluded

THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 499

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

over a period and could not be replaced withoutreoperation. Terblanche'05 described the path ofa U tube through the bile duct tumor and outthrough the liver, which could be replaced at willin a physician's office or in an x-ray departmentby simple railroading without the need for furtheroperative procedure. This simple operative pro-cedure resulted in the survival of some of hispatients for six years or longer.Tumors treated by the placement of U tubes

extending through the liver and brought outthrough a Roux-en-Y loop have been offeringfairly good palliation for periods of one to sixyears in reports from Cameron and colleagues.71We have found, however, that these tubes need toto be changed frequently, with considerable dis-comfort to the patient, and that it is possible tolocally resect tumors of the hepatic ducts andbifurcation of the hepatic ducts and extend theexcision up into the secondary hepatic ducts soas to achieve not only palliation but potentialcures in some of these patients (Figure 16). Trans-hepatic tubes are used as a stent..

Attempts to excise these tumors have met withvarious success, with reports coming from Japan,France and the United States the past five yearsand articles by Corlette and Bookwalter'08 andHart and White,7; as well as several others.'07'109At the present time a number of surgeons (includ-ing this author) are carrying out resection of themiddle portion of the liver high up into thesecondary ducts with bilateral hepaticojejunos-tomy, with some patients surviving without evi-dence of disease for as long as five years (Figure16). Other authors are advocating resection of theright or left lobe of the liver, together with theportion of the upper bile ducts involved by tumor,and a third group of individuals is advocating re-moval of a portion of segment four or five in theright lobe. Also, many patients are still beingtreated with a U tube placed through the commonand hepatic bile ducts to the anterior surface ofthe liver. Finally, percutanleous drainage is beingused to decompress some patients in whom thediagnosis of carcinoma of the bile ducts has beenmade on the basis of percutaneous biopsies intumors that appear very large on CT scan andultrasound studies.

All of these approaches include decompressionof the biliary tree, which results in fewer prob-lems of sepsis, cholangitis and liver failure. Thethird, fourth and fifth approaches can be supple-mented by radiation therapy, which appears to

offer short-term palliation to these individuals,lengthening life for as long as six months to ayear. Intraoperative radiotherapy has been advo-cated for patients with carcinoma at the hilus ofthe hepatic bile duct that involves the commonhepatic artery or portal vein or that spreads toboth right and left intrahepatic bile ducts (when itssize does not extend beyond the field of radiation).Under these circumstances, laparotomy is carriedout and external drainage is applied to relievejaundice. A treatment cone is then positioneddirectly at the site of the tumor, the correct posi-tion is determined and radiotherapy is adminis-tered with an electron beam from a Betatron orlinear accelerator, with a single dose of 3,000rads and 11 to 18 meV delivered to the lesion.All patients treated thus by Iwasaki and associ-ates'06 had slight relief of bile duct obstruction.

Another approach is that of placing radioactivegold seeds around the tumor at the time of opera-tion. Combined with external radiotherapy, thismay be of some value. The place of radiationtherapy in cancer of the extrahepatic biliary sys-tem is being evaluated, both in the United Statesand Japan, from the point of view of curativetherapy postoperatively to decrease local recur-rences and increase the length and quality of sur-vival and to treat incisional recurrences. In ad-vanced disease management the aim is to increasethe effectiveness and length of palliation and, inconjunction with chemotherapy, to further con-solidate therapeutic gains made with radiotherapyalone.10"-113

Pancreatic Cancer and PancreatitisCancer of the pancreas is asymptomatic in its

earliest stages; later it is evident by epigastric orback pain, jaundice and weight loss. Jaundice anda palpable gallbladder are usually the only physi-cal findings in early cases. The same type ofstudies are used to diagnose obstructive jaundiceon this basis as are used for the diagnosis of pan-creatic cancer. A number of collaborative studieshave been carried out on the diagnosis of pan-creatic cancer using ultrasonography, computer-ized tomography, radionuclide scanning, ERCP,selective celiac and superior mesenteric angiog-raphy, duodenal drtinage studies, cytologic studiesand serum carcinoembryonic antigen and pan-creatic oncofetal antigen assays. Most test findingshave shown that a patient had either pancreaticcancer or pancreatitis. Cytologic examination witha positive result confirmed the presence of cancer

500 JUNE 1982 * 136 * 6

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

but only about a third of patients were therebycorrectly diagnosed. If a negative result is takento indicate pancreatitis, then 99 percent of all pa-tients were diagnosed with a 75 percent accuracy.

Comparative results between ultrasound andCT scans have shown little difference. Ultrasonog-raphy is preferred on the basis of cost effectivenessbut a combination may be more useful. ERCP wasmore accurate than duodenal drainage studies.Angiography is invasive and time-consuming andthere is some difficulty with it in distinguishingbetween cancer and pancreatitis. Blood tests havebeen largely nonspecific. Therefore, gray-scaleultrasonography is probably the best noninvasivetest for differentiating between pancreatic cancerand pancreatitis. CT scans are as good or su-perior but are more expensive. Other types ofimaging procedures contribute little to this differ-entiation. ERCP is probably even more accurateand better at differentiating among the diagnosesof chronic pancreatitis, cancer and other lesionsin this area."14-"7 The general treatment of pan-creatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis is outsidethe realm of this paper, but jaundice in advancedcases can be treated as described earlier. Thejaundice due to compression of the distal duct bychronic pancreatitis can be treated by choledocho-duodenostomy or choledochojejunostomy.

Congenital Diseases of the Biliary TractBiliary A tresia

Congenital biliary atresia had been poorly de-fined up until 30 years ago. In 1953 Gross"8 re-viewed 198 patients with obstructive jaundice, 183of which were treated surgically, 26 successfully,for inspissated mucus or bile in the ducts that wastreated by manipulation and irrigation of theducts.68 Only 12 of these patients had adequatebiliary drainage achieved by duct-enteric anasto-mosis. Only 53 (26 percent) were relieved bymedical or surgical therapy for a year or more.

There has been considerable question as to thecause of this type of lesion, whether it was due toarrested development during a solid stage, to avariety of congenital or developmental anomalyor to some type of hepatitis or cholangitis. Treat-ment in former years was one of delay of operationuntil the jaundice, if due to hepatitis, could havecleared. After the introduction in 1959 of a pro-cedure for hepatic portoenterostomy by Kasaiand associates,119 emphasis has been on earlyoperation, preferably in the first one to two monthsat a time when it is still impossible to differentiate

the hepatitis of newborn from congenital biliaryatresia.

Experience with this operation has encouragedthe notion that neonatal hepatitis and extrahepaticatresia are different results of a single basic processoccurring immediately after birth.'20 The sugges-tion is that the process is probably viral in origin,causing inflammation with varying degrees of livercell and duct epithelial injury, followed by obliter-ation of the bile ducts and later scarring. Thesuggestion is that the progressive scarring of theductal system may be halted or even reversed byresection of the extrahepatic ducts, combined witha bile drainage procedure such as has been pro-posed by Professor Kasai and co-workers.119 Thepossibility that many of these cases are the resultof an obstructive cholangitis of varying degreesrather than an unalterable developmental anomalygives a different point of view relative to the out-come.

It is difficult to separate the congenital fromthe inflammatory type of biliary atresia at thepresent time. Kasai attempts to enhance biliarydrainage by removing all of the obstructed or po-tentially obstructed extrahepatic ductal systemand draining the hepatic ducts into a defunction-alized loop of jejunum. Lilly,'12 A. H. Bill, MD (per-sonal communication, April 28, 1981) and manyother surgeons throughout the world have con-firmed the presence of bile duct drainage from theliver following this procedure for jaundice of new-borns. Kasai and associates' first patient was aliveand well 18 years later. Twenty out of Kasai's 80patients were alive without jaundice, 14 for morethan two years after operation in one recent re-port.119 The main problem with this procedure hasbeen one of postoperative cholangitis that in turnmay lead to cirrhosis and portal hypertension evenafter decompression and relief of jaundice.

Miyata and colleagues'22 reported that 15 of 51patients were completely relieved of jaundice,portal hypertension developed in 7 of the 15 and4 died. Most of the patients later showed transientepisodes of cholangitis. Also, in a substantial num-ber of patients who were relieved -of jaundice cir-rhosis of the liver later developed and they diedof their disease. It is still unclear as to the dividingline between true extrahepatic atresia on a con-genital basis with intrahepatic changes compar-able with acquired biliary obstruction in olderpeople, biliary hypoplasia with varying degrees ofreduction in size of the extrahepatic ducts withintrahepatic cirrhosis and those with inflammatory

THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 501

OBSTRUCTIVE BILIARY TRACT DISEASE

neonatal hepatitis. It seems logical that most casesof neonatal jaundice, excluding rare, truly devel-opmental anomalies, are the result of an ongoingor dynamic process, possibly similar to sclerosingcholangitis in adults. The overlap between hepato-biliary pathology and the clinical course makes itvery difficult to clearly differentiate those patientswith inflammatory neonatal hepatitis from thosewith congenital atresic malformations.

Biliary Cystic Dilatation

The current classification of cystic dilatationsof the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary sys-tems was suggested by Alonso-Lej in 1959, dis-cussed by Flanigan'23 in 1975. In this classifica-tion, type I cysts, or about 80 percent of the total,include dilatations of the common bile duct andcommon hepatic duct. Subgroups IA, IB and ICwere described later. The rare type II cysts arediverticula of the common bile duct.123 Type IIIcysts, or choledochoceles, are intraduodenal cysticdilatations of the terminal common bile duct thatmay be lined by either duodenal or bile ductmucosa. Intrahepatic cystic dilatations that pre-sent alone or in combination with extrahepaticdilatation are now called Caroli's disease.124 Cho-ledochal cysts with clinical signs of right upperquadrant pain, obstructive jaundice and a massare obvious in about a third of patients and thediagnosis is obscure in the others.125'126 About athird of reported cases come from Japan; threequarters of patients are female. A fourth of suchcysts are discovered before the age of one and60 percent before the age of ten. The diagnosiswas formerly made chiefly at operation but, withthe advent of ultrasound and ERCP, most suchpatients are now diagnosed preoperatively.124"27

Type II and III cysts have been and are stillsimply excised and managed by internal drainage.Type I cysts were formerly treated mainly by in-ternal drainage procedures to the stomach duode-num but now are treated by excision and anasto-mosis to a jejunal loop.'25"28 The complicationsthat arise in unoperated patients includecholangitis, common bile duct stone formation,common bile duct stricture, obstructive jaundice,portal hypertension, biliary cirrhosis, rupture ofcysts, development of bile duct cancer and pan-creatitis.12'9.10 It is for this reason that externalrather than internal drainage and excision withanastomosis to a Roux-en-Y loop are now carriedout. This procedure seems at the present time tobe the treatment of choice. It is possible, how-

ever, to leave the posterior wall of the cyst in placeto avoid injury to the structure. In this case thecyst wall is opened anteriorly and the lining of thecyst in the anterior and lateral walls is removed.Reconstruction is then carried out with an hepa-ticojejunostomy or choledochojejunostomy.125"129

REFERENCES1. Schein CJ: Postcholecystectomy Syndromes-A Clinical Ap-

proach to Etiology, Diagnosis & Management. Hagerstown, MD,Harper & Row, 1978

2. White TT, Sarles H, Benhamou J-P: Liver, Bile Ducts, andPancreas. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1977

3. Bouchier IAD (Ed): Diseases of the biliary tract. ClinGastroenterol 1973; 2:1-215

4. White 1T, Harrison RC: Reoperative Gastrointestinal Sur-gery, 2nd Ed. Boston, Little, Brown, 1979

5. Kune G, Sali A: Current Practice of Biliary Surgery, 2nd Ed.Boston, Blackwell Scientific, 1980

6. Berk RN, Clemett AR: Radiology of the Gallbladder andBile Ducts. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1977

7. Ferrucci JT Jr: Body ultrasonography. N Engl J Med 1979Mar 8, Mar 15; 300 (10,11):538-542; 590-602

8. Behan M, Kazam E: Sonography of the common bile duct:Value of the right anterior oblique view. AJR 1978 Apr; 130:701-709

9. Cooperberg PL, Li D, Wong P, et al: Accuracy of commonhepatic duct size in the evaluation of extrahepatic biliary obstruc-tion. Radiology 1980 Apr; 135:141-144

10. Deitch EA: The reliability and clinical limitations of sono-graphic scanning of the biliary ducts. Ann Surg 1981; 194:167-170

11. Ulreich S, Foster KW, Stier SA, et al: Acute cholecystitis-Comparison of ultrasound and intravenous cholangiography. ArchSurg 1980 Feb; 115:158-160

12. Sample WF, Sarti DA, Goldstein LI, et al: Gray-scale ultra-sonography of the jaundiced patient. Radiology 1978 Sep; 128(3):719-725

13. Gregg JA, McDonald DG: Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography and gray-scale abdominal ultrasound in the diag-nosis of jaundice. Am J Surg 1979 May; 137:611-615

14. Goldberg HI, Filly RA, Korobkin M, et al: Capability ofCT body scanning and ultrasonography to demonstrate the statusof the biliary ductal system in patients with jaundice. Radiology1978 Dec; 129:731-737

15. Weissmann HS, Frank M, Rosenblatt R, et al: Cholescin-tigraphy, ultrasonography and computerized tomography in theevaluation of biliary tract disorders. Semin Nuct Med 1979 Jan;9: 22-35

16. Weissmann HS, Frank MS, Bernstein LH, et al: Rapid andaccurate diagnosis of acute cholecystitis with 99mTc-HIDA cho-lescintigraphy. AJR 1979 Apr; 132:523-528

17. Suarez CA, Block F, Bernstein D, et al: The role of HIDA/PIPIDA scanning in diagnosing cystic duct obstruction. Ann Surg1980 Apr; 191:391-396

18. Szlabick RE, Catto JA, Fink-Bennett D, et al: Hepatobiliaryscanning in the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. Arch Surg 1980Apr; 115:540-544

19. Carter RF, Saypol GM: Transabdominal cholangiography.JAMA 1952; 148:253-255

20. Arner 0, Hagberg S, Seldinger SI: Percutaneous transhepaticcholangiography: Puncture of dilated and nondilated bile ductsunder roentgen television control. Surgery 1962; 52:561-571

21. Okuda K, Tanikawa K, Emura T, et al: Nonsurgical, per-cutaneous transhepatic cholangiography-Diagnostic significance inmedical problems of the liver. Am J Dig Dis 1974 Jan; 19:21-36

22. Elias E, Hamlyn AN, Jain S, et al: A randomized trial ofpercutaneous transhepatic cholangiography with the Chiba needleversus endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for bile duct visual-ization in jaundice. Gastroenterology 1976 Sep; 71(3):439-443

23. Juler GL, Conroy RM, Fuelleman RW: Bile leakage follow-ing percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography with the Chibaneedle. Arch Surg 1977 Aug; 112:954-958

24. Pollock TW, Ring ER, Oleaga JA, et al: Percutaneous de-compression of benign and malignant biliary obstruction. ArchSurg 1979 Feb; 114:148-151

25. Hansson JA, Hoevels J, Simert G, et al: Clinical aspects ofnonsurgical percutaneous transhepatic bile drainage in obstructivelesions of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Ann Surg 1979 Jan; 189:58-61

26. Hoevels J, Ihse I: Percutaneous transhepatic insertion of apermanent endoprosthesis in obstructive lesions of the extrahepaticbile ducts. Gastrointest Radiol 1979 Nov 15; 4(4):367-377