NCC Pediatrics Continuity Clinic Curriculum: Toxic Stress ... · of health, learning, and behavior...

Transcript of NCC Pediatrics Continuity Clinic Curriculum: Toxic Stress ... · of health, learning, and behavior...

NCC Pediatrics Continuity Clinic Curriculum:

Toxic Stress and Adverse Childhood

Experiences Faculty Guide

Goals & Objectives: To understand toxic stress, its adverse effects on children, and how children and their families

can overcome these negative health effects

Define toxic stress.

o How do stress responses differ?

What determines whether an adverse childhood experience (ACE) may be associated

with a toxic stress response?

What is the Adverse Childhood Experiences study?

How does toxic stress affect the developing brain?

What are the potential health consequences of toxic stress?

What is resilience?

Pre-Meeting Preparation: Please review the following enclosures: Watch the TEDTalk on ACEs by Nadine Burke-Harris, MD, MPH, FAAP:

https://youtu.be/95ovIJ3dsNk

Read AAP Technical Report “The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and

Toxic Stress”

Read Military Children and Families: Strengths and Challenges During Peace and War

(begin at “Strengths and Challenges Among Military Children and Families” pg. 66 and

stop at “Strengths-Based Approaches” pg. 68, or continue through for extra credit 😊)

Conference Agenda: Quiz

Cases

Extra Credit: ● ACEs study

© Developed by CPT Saira Ahmed, CPT Christin Folker, Edited by CPT W.

Aaron Adams, 2018. Updates Christin Folker, 2019.

TECHNICAL REPORT

The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity andToxic Stress

abstractAdvances in fields of inquiry as diverse as neuroscience, molecularbiology, genomics, developmental psychology, epidemiology, sociology,and economics are catalyzing an important paradigm shift in our un-derstanding of health and disease across the lifespan. This converging,multidisciplinary science of human development has profound impli-cations for our ability to enhance the life prospects of children and tostrengthen the social and economic fabric of society. Drawing on thesemultiple streams of investigation, this report presents an ecobiodeve-lopmental framework that illustrates how early experiences and envi-ronmental influences can leave a lasting signature on the geneticpredispositions that affect emerging brain architecture and long-termhealth. The report also examines extensive evidence of the disruptiveimpacts of toxic stress, offering intriguing insights into causal mech-anisms that link early adversity to later impairments in learning, be-havior, and both physical and mental well-being. The implications ofthis framework for the practice of medicine, in general, and pediatrics,specifically, are potentially transformational. They suggest that manyadult diseases should be viewed as developmental disorders that beginearly in life and that persistent health disparities associated with pov-erty, discrimination, or maltreatment could be reduced by the allevi-ation of toxic stress in childhood. An ecobiodevelopmental frameworkalso underscores the need for new thinking about the focus and bound-aries of pediatric practice. It calls for pediatricians to serve as bothfront-line guardians of healthy child development and strategically po-sitioned, community leaders to inform new science-based strategiesthat build strong foundations for educational achievement, economicproductivity, responsible citizenship, and lifelong health. Pediatrics2012;129:e232–e246

INTRODUCTIONOf a good beginning cometh a good end.

John Heywood, Proverbs (1546)

The United States, like all nations of the world, is facing a numberof social and economic challenges that must be met to securea promising future. Central to this task is the need to produce a well-educated and healthy adult population that is sufficiently skilled toparticipate effectively in a global economy and to become responsiblestakeholders in a productive society. As concerns continue to growabout the quality of public education and its capacity to prepare thenation’s future workforce, increasing investments are being made in

Jack P. Shonkoff, MD, Andrew S. Garner, MD, PhD, and THECOMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD ANDFAMILY HEALTH, COMMITTEE ON EARLY CHILDHOOD,ADOPTION, AND DEPENDENT CARE, AND SECTION ONDEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRICS

KEY WORDSecobiodevelopmental framework, new morbidity, toxic stress,social inequalities, health disparities, health promotion, diseaseprevention, advocacy, brain development, human capitaldevelopment, pediatric basic science

ABBREVIATIONSACE—adverse childhood experiencesCRH—corticotropin-releasing hormoneEBD—ecobiodevelopmentalPFC—prefrontal cortex

This document is copyrighted and is property of the AmericanAcademy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authorshave filed conflict of interest statements with the AmericanAcademy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved througha process approved by the Board of Directors. The AmericanAcademy of Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted anycommercial involvement in the development of the content ofthis publication.

The guidance in this report does not indicate an exclusivecourse of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care.Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may beappropriate.

All technical reports from the American Academy of Pediatricsautomatically expire 5 years after publication unless reaffirmed,revised, or retired at or before that time.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2011-2663

doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2012 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

e232 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICSby 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

the preschool years to promote thefoundations of learning. Althoughdebates about early childhood policyfocus almost entirely on educationalobjectives, science indicates thatsound investments in interventionsthat reduce adversity are also likely tostrengthen the foundations of physicaland mental health, which would gen-erate even larger returns to all ofsociety.1,2 This growing scientific un-derstanding about the common rootsof health, learning, and behavior inthe early years of life presents a po-tentially transformational opportunityfor the future of pediatrics.

Identifying the origins of adult diseaseand addressing them early in life arecritical steps toward changing ourcurrent health care system from a“sick-care” to a “well-care” model.3–5

Although new discoveries in basicscience, clinical subspecialties, andhigh-technology medical interventionscontinue to advance our capacity totreat patients who are ill, there isgrowing appreciation that a success-ful well-care system must expand itsscope beyond the traditional realm ofindividualized, clinical practice to ad-dress the complex social, economic,cultural, environmental, and devel-opmental influences that lead topopulation-based health disparitiesand unsustainable medical care ex-penditures.2,6,7 The science of earlychildhood development has much tooffer in the realization of this vision,and the well-being of young childrenand their families is emerging as apromising focus for creative invest-ment.

The history of pediatrics conveys a richnarrative of empirical investigationand pragmatic problem solving. Itsemergence as a specialized domainof clinical medicine in the late 19thcentury was dominated by concernsabout nutrition, infectious disease, andpremature death. In the middle of

the 20th century, as effective vaccines,antibiotics, hygiene, and other publichealth measures confronted the in-fectious etiologies of childhood illness,a variety of developmental, behavioral,and family difficulties became knownas the “new morbidities.”8 By the endof the century, mood disorders, pa-rental substance abuse, and exposureto violence, among other conditions,began to receive increasing attentionin the pediatric clinical setting andbecame known as the “newer mor-bidities.”9 Most recently, increasinglycomplex mental health concerns; theadverse effects of television viewing;the influence of new technologies; ep-idemic increases in obesity; and per-sistent economic, racial, and ethnicdisparities in health status have beencalled the “millennial morbidities.”10

Advances in the biological, develop-mental, and social sciences now offertools to write the next importantchapter. The overlapping and syner-gistic characteristics of the mostprevalent conditions and threats tochild well-being—combined with theremarkable pace of new discoveriesin developmental neuroscience, ge-nomics, and the behavioral and socialsciences—present an opportunity toconfront a number of important ques-tions with fresh information and anew perspective. What are the bi-ological mechanisms that explain thewell-documented association betweenchildhood adversity and adult healthimpairment? As these causal mecha-nisms are better elucidated, what canthe medical field, specifically, and so-ciety, more generally, do to reduce ormitigate the effects of disruptiveearly-life influences on the origins oflifelong disease? When is the optimaltime for those interventions to beimplemented?

This technical report addresses theseimportant questions in 3 ways. First,it presents a scientifically grounded,

ecobiodevelopmental (EBD) frameworkto stimulate fresh thinking about thepromotion of health and prevention ofdisease across the lifespan. Second, itapplies this EBD framework to betterunderstand the complex relationshipsamong adverse childhood circum-stances, toxic stress, brain architec-ture, and poor physical and mentalhealth well into adulthood. Third, itproposes a new role for pediatriciansto promote the development and im-plementation of science-based strate-gies to reduce toxic stress in earlychildhood as a means of preventingor reducing many of society’s mostcomplex and enduring problems,which are frequently associated withdisparities in learning, behavior, andhealth. The magnitude of this latterchallenge cannot be overstated. A re-cent technical report from the Amer-ican Academy of Pediatrics reviewed58 years of published studies andcharacterized racial and ethnic dis-parities in children’s health to be ex-tensive, pervasive, persistent, and, insome cases, worsening.11 Moreover,the report found only 2 studies thatevaluated interventions designed toreduce disparities in children’s healthstatus and health care that also com-pared the minority group to a whitegroup, and none used a randomizedcontrolled trial design.

The causal sequences of risk thatcontribute to demographic differencesin educational achievement and physi-cal well-being threaten our country’sdemocratic ideals by undermining thenational credo of equal opportunity.Unhealthy communities with too manyfast food franchises and liquor stores,yet far too few fresh food outletsand opportunities for physical activity,contribute to an unhealthy population.Unemployment and forced mobilitydisrupt the social networks that sta-bilize communities and families and,thereby, lead to higher rates of violence

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 1, January 2012 e233

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

by 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

and school dropout. The purpose ofthis technical report is to leverage newknowledge from the biological andsocial sciences to help achieve thepositive life outcomes that could beaccrued to all of society if more effec-tive strategies were developed to re-duce the exposure of young childrento significant adversity.

A NEW FRAMEWORK FORPROMOTING HEALTHYDEVELOPMENT

Advances in our understanding ofthe factors that either promote orundermine early human developmenthave set the stage for a significantparadigm shift.12 In simple terms, theprocess of development is now un-derstood as a function of “naturedancing with nurture over time,” incontrast to the longstanding but nowoutdated debate about the influenceof “nature versus nurture.”13 That isto say, beginning prenatally, continu-ing through infancy, and extendinginto childhood and beyond, develop-ment is driven by an ongoing, in-extricable interaction between biology(as defined by genetic predisposi-tions) and ecology (as defined by thesocial and physical environment)12,14,15

(see Fig 1).

Building on an ecological model thatexplains multiple levels of influenceon psychological development,16 and arecently proposed biodevelopmentalframework that offers an integrated,science-based approach to coordinated,early childhood policy making andpractice across sectors,17 this techni-cal report presents an EBD frameworkthat draws on a recent report fromthe Center on the Developing Child atHarvard University to help physiciansand policy makers think about howearly childhood adversity can lead tolifelong impairments in learning, be-havior, and both physical and mentalhealth.1,6

Some of the most compelling newevidence for this proposed frameworkcomes from the rapidly moving fieldof epigenetics, which investigates themolecular biological mechanisms (suchas DNA methylation and histone acet-ylation) that affect gene expressionwithout altering DNA sequence. Forexample, studies of maternal care inrats indicate that differences in thequality of nurturing affect neuralfunction in pups and negatively affectcognition and the expression of psy-chopathology later in life. Moreover,rats whose mothers showed increasedlevels of licking and grooming duringtheir first week of life also showed lessexaggerated stress responses as adultscompared with rats who were rearedby mothers with a low level of lickingand grooming, and the expression ofmother-pup interactions in the pups

has been demonstrated to be passedon to the next generation.18–22 Thisburgeoning area of research is chal-lenging us to look beyond geneticpredispositions to examine how envi-ronmental influences and early expe-riences affect when, how, and to whatdegree different genes are actuallyactivated, thereby elucidating themechanistic linkages through whichgene-environment interaction can af-fect lifelong behavior, development,and health (see Fig 1).

Additional evidence for the proposedframework comes from insights ac-crued during the “Decade of theBrain” in the 1990s, when the NationalInstitutes of Health invested signifi-cant resources into understandingboth normal and pathologic neuronaldevelopment and function. Subse-quent advances in developmentalneuroscience have begun to describefurther, in some cases at the molec-ular and cellular levels, how an in-tegrated, functioning network withbillions of neurons and trillions ofconnections is assembled. Becausethis network serves as the biologicalplatform for a child’s emerging social-emotional, linguistic, and cognitiveskills, developmental neuroscience isalso beginning to clarify the under-lying causal mechanisms that explainthe normative process of child de-velopment. In a parallel fashion, lon-gitudinal studies that document thelong-term consequences of childhoodadversity indicate that alterations ina child’s ecology can have measurableeffects on his or her developmentaltrajectory, with lifelong consequencesfor educational achievement, economicproductivity, health status, and lon-gevity.23–27

The EBD framework described in thisarticle presents a new way to thinkabout the underlying biological mech-anisms that explain this robust linkbetween early life adversities (ie, the

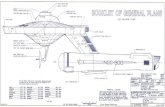

FIGURE 1The basic science of pediatrics. An emerging,multidisciplinary science of development sup-ports an EBD framework for understanding theevolution of human health and disease acrossthe life span. In recent decades, epidemiology,developmental psychology, and longitudinalstudies of early childhood interventions havedemonstrated significant associations (hashedred arrow) between the ecology of childhoodand a wide range of developmental outcomesand life course trajectories. Concurrently, ad-vances in the biological sciences, particularly indevelopmental neuroscience and epigenetics,have made parallel progress in beginning toelucidate the biological mechanisms (solidarrows) underlying these important associa-tions. The convergence of these diverse dis-ciplines defines a promising new basic scienceof pediatrics.

e234 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICSby 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

new morbidities of childhood) and im-portant adult outcomes. The innovationof this approach lies in its mobilizationof dramatic scientific advances in theservice of rethinking basic notions ofhealth promotion and disease pre-vention within a fully integrated, lifespan perspective from conception toold age.6 In this context, significantstress in the lives of young children isviewed as a risk factor for the genesisof health-threatening behaviors as wellas a catalyst for physiologic respon-ses that can lay the groundwork forchronic, stress-related diseases laterin life.

Understanding the Biology ofStress

Although genetic variability clearlyplays a role in stress reactivity, earlyexperiences and environmental influ-ences can have considerable impact.Beginning as early as the prenatal pe-riod, both animal28–30 and human31,32

studies suggest that fetal exposure tomaternal stress can influence laterstress responsiveness. In animals, thiseffect has been demonstrated notonly in the offspring of the studiedpregnancy but also in subsequentgenerations. The precise biologicalmechanisms that explain these find-ings remain to be elucidated, butepigenetic modifications of DNA ap-pear likely to play a role.31,33,34 Earlypostnatal experiences with adversityare also thought to affect future re-activity to stress, perhaps by alteringthe developing neural circuits con-trolling these neuroendocrine respon-ses.34,35 Although much researchremains to be performed in this area,there is a strong scientific consensusthat the ecological context modulatesthe expression of one’s genotype. Itis as if experiences confer a “sig-nature” on the genome to authorizecertain characteristics and behaviorsand to prohibit others. This concept

underscores the need for greater un-derstanding of how stress “gets underthe skin,” as well as the importanceof determining what external and in-ternal factors can be mobilized toprevent that embedding process orprotect against the consequences ofits activation.

Physiologic responses to stress arewell defined.36–38 The most exten-sively studied involve activation of thehypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocorticalaxis and the sympathetic-adrenomedullarysystem, which results in increasedlevels of stress hormones, such ascorticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH),cortisol, norepinephrine, and adrena-line. These changes co-occur witha network of other mediators thatinclude elevated inflammatory cyto-kines and the response of the para-sympathetic nervous system, whichcounterbalances both sympatheticactivation and inflammatory respon-ses. Whereas transient increases inthese stress hormones are protectiveand even essential for survival, ex-cessively high levels or prolongedexposures can be quite harmful orfrankly toxic,39–41 and the dysregulationof this network of physiologicmediators (eg, too much or too littlecortisol; too much or too little in-flammatory response) can lead toa chronic “wear and tear” effecton multiple organ systems, includingthe brain.39–41 This cumulative, stress-induced burden on overall body func-tioning and the aggregated costs, bothphysiologic and psychological, re-quired for coping and returning tohomeostatic balance, have been re-ferred to as “allostatic load.”38,42–44

The dynamics of these stress-mediatingsystems are such that their over-activation in the context of repeated orchronic adversity leads to alterationsin their regulation.

The National Scientific Council onthe Developing Child has proposed

a conceptual taxonomy comprising 3distinct types of stress responses (incontrast to the actual stressors them-selves) in young children—positive,tolerable, and toxic—on the basis ofpostulated differences in their po-tential to cause enduring physiologicdisruptions as a result of the intensityand duration of the response.17,45 Apositive stress response refers toa physiologic state that is brief andmild to moderate in magnitude. Cen-tral to the notion of positive stress isthe availability of a caring and re-sponsive adult who helps the childcope with the stressor, thereby pro-viding a protective effect that facili-tates the return of the stress responsesystems back to baseline status. Ex-amples of precipitants of a positivestress response in young children in-clude dealing with frustration, gettingan immunization, and the anxiety as-sociated with the first day at a childcare center. When buffered by an en-vironment of stable and supportiverelationships, positive stress respon-ses are a growth-promoting elementof normal development. As such, theyprovide important opportunities toobserve, learn, and practice healthy,adaptive responses to adverse expe-riences.

A tolerable stress response, in con-trast to positive stress, is associatedwith exposure to nonnormative expe-riences that present a greater magni-tude of adversity or threat. Precipitantsmay include the death of a familymember, a serious illness or injury,a contentious divorce, a natural di-saster, or an act of terrorism. Whenexperienced in the context of buffer-ing protection provided by suppor-tive adults, the risk that suchcircumstances will produce excessiveactivation of the stress responsesystems that leads to physiologicharm and long-term consequencesfor health and learning is greatly

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 1, January 2012 e235

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

by 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

reduced. Thus, the essential char-acteristic that makes this form ofstress response tolerable is theextent to which protective adultrelationships facilitate the child’s adap-tive coping and a sense of control,thereby reducing the physiologic stressresponse and promoting a return tobaseline status.

The third and most dangerous form ofstress response, toxic stress, can re-sult from strong, frequent, or pro-longed activation of the body’s stressresponse systems in the absence ofthe buffering protection of a supportive,adult relationship. The risk factorsstudied in the Adverse ChildhoodExperiences Study23 include examplesof multiple stressors (eg, child abuseor neglect, parental substance abuse,and maternal depression) that arecapable of inducing a toxic stress re-sponse. The essential characteristic ofthis phenomenon is the postulateddisruption of brain circuitry and otherorgan and metabolic systems dur-ing sensitive developmental periods.Such disruption may result in ana-tomic changes and/or physiologicdysregulations that are the precursorsof later impairments in learning andbehavior as well as the roots of chronic,stress-related physical and mental ill-ness. The potential role of toxic stressand early life adversity in the patho-genesis of health disparities under-scores the importance of effectivesurveillance for significant risk factorsin the primary health care setting. Moreimportant, however, is the need forclinical pediatrics to move beyond thelevel of risk factor identification and toleverage advances in the biology of ad-versity to contribute to the critical taskof developing, testing, and refining newand more effective strategies for re-ducing toxic stress and mitigating itseffects as early as possible, beforeirrevocable damage is done. Statedsimply, the next chapter of innovation

in pediatrics remains to be written,but the outline and plot are clear.

Toxic Stress and the DevelopingBrain

In addition to short-term changes inobservable behavior, toxic stress inyoung children can lead to less out-wardly visible yet permanent changesin brain structure and function.39,46

The plasticity of the fetal, infant, andearly childhood brain makes it par-ticularly sensitive to chemical influ-ences, and there is growing evidencefrom both animal and human studiesthat persistently elevated levels ofstress hormones can disrupt its de-veloping architecture.45 For example,abundant glucocorticoid receptors arefound in the amygdala, hippocampus,and prefrontal cortex (PFC), and ex-posure to stressful experiences hasbeen shown to alter the size andneuronal architecture of these areasas well as lead to functional differ-ences in learning, memory, and as-pects of executive functioning. Morespecifically, chronic stress is associ-ated with hypertrophy and overactivityin the amygdala and orbitofrontalcortex, whereas comparable levels ofadversity can lead to loss of neuronsand neural connections in the hippo-campus and medial PFC. The functionalconsequences of these structuralchanges include more anxiety relatedto both hyperactivation of the amyg-dala and less top-down control as aresult of PFC atrophy as well as im-paired memory and mood control asa consequence of hippocampal re-duction.47 Thus, the developing archi-tecture of the brain can be impairedin numerous ways that create a weakfoundation for later learning, behav-ior, and health.

Along with its role in mediating fearand anxiety, the amygdala is also anactivator of the physiologic stressresponse. Its stimulation activates

sympathetic activity and causes neu-rons in the hypothalamus to releaseCRH. CRH, in turn, signals the pituitaryto release adrenocorticotropic hor-mone, which then stimulates theadrenal glands to increase serumcortisol concentrations. The amygdalacontains large numbers of both CRHand glucocorticoid receptors, begin-ning early in life, which facilitate theestablishment of a positive feedbackloop. Significant stress in early child-hood can trigger amygdala hypertro-phy and result in a hyperresponsiveor chronically activated physiologicstress response, along with increasedpotential for fear and anxiety.48,49 It isin this way that a child’s environmentand early experiences get under theskin.

Although the hippocampus can turnoff elevated cortisol, chronic stressdiminishes its capacity to do so andcan lead to impairments in memoryand mood-related functions that arelocated in this brain region. Exposureto chronic stress and high levels ofcortisol also inhibit neurogenesis inthe hippocampus, which is believed toplay an important role in the encodingof memory and other functions. Fur-thermore, toxic stress limits the abilityof the hippocampus to promote con-textual learning, making it more dif-ficult to discriminate conditions forwhich there may be danger versussafety, as is common in posttraumaticstress disorder. Hence, altered brainarchitecture in response to toxic stressin early childhood could explain, atleast in part, the strong associationbetween early adverse experiencesand subsequent problems in the de-velopment of linguistic, cognitive, andsocial-emotional skills, all of which areinextricably intertwined in the wiringof the developing brain.45

The PFC also participates in turningoff the cortisol response and hasan important role in the top-down

e236 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICSby 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

regulation of autonomic balance (ie,sympathetic versus parasympatheticeffects), as well as in the develop-ment of executive functions, such asdecision-making, working memory,behavioral self-regulation, and moodand impulse control. The PFC is alsoknown to suppress amygdala activity,allowing for more adaptive responsesto potentially threatening or stress-ful experiences; however, exposure tostress and elevated cortisol results indramatic changes in the connectivitywithin the PFC, which may limit itsability to inhibit amygdala activity and,thereby, impair adaptive responses tostress. Because the hippocampus andPFC both play a significant role inmodulating the amygdala’s initiationof the stress response, toxic stress–induced changes in architecture andconnectivity within and between theseimportant areas might accountfor the variability seen in stress-responsiveness.50 This can then resultin some children appearing to be bothmore reactive to even mildly adverseexperiences and less capable of effec-tively coping with future stress.36,37,45,51

Toxic Stress and the EarlyChildhood Roots of LifelongImpairments in Physical andMental Health

As described in the previous section,stress-induced changes in the archi-tecture of different regions of thedeveloping brain (eg, amygdala, hip-pocampus, and PFC) can have poten-tially permanent effects on a range ofimportant functions, such as regulat-ing stress physiology, learning newskills, and developing the capacityto make healthy adaptations to futureadversity.52,53 As the scientific evi-dence for these associations has be-come better known and has beendisseminated more widely, its impli-cations for early childhood policy andprograms have become increasingly

appreciated by decision makersacross the political spectrum. Not-withstanding this growing awareness,however, discussions about earlybrain development in policy-makingcircles have focused almost entirelyon issues concerned with schoolreadiness as a prerequisite for lateracademic achievement and the de-velopment of a skilled adult work-force. Within this same context, thehealth dimension of early childhoodpolicy has focused largely on the tra-ditional components of primary pedi-atric care, such as immunizations,early identification of sensory im-pairments and developmental delays,and the prompt diagnosis and treat-ment of medical problems. That said,as advances in the biomedical scienceshave generated growing evidencelinking biological disruptions associ-ated with adverse childhood experi-ences (ACE) to greater risk for a varietyof chronic diseases well into the adultyears, the need to reconceptualizethe health dimension of early child-hood policy has become increasinglyclear.1,6 Stated simply, the time hascome to expand the public’s un-derstanding of brain developmentand shine a bright light on its re-lation to the early childhood rootsof adult disease and to examine thecompelling implications of this grow-ing knowledge base for the future ofpediatric practice.

The potential consequences of toxicstress in early childhood for thepathogenesis of adult disease areconsiderable. At the behavioral level,there is extensive evidence of a stronglink between early adversity and awide range of health-threatening be-haviors. At the biological level, there isgrowing documentation of the extentto which both the cumulative burdenof stress over time (eg, from chronicmaltreatment) and the timing ofspecific environmental insults during

sensitive developmental periods (eg,from first trimester rubella or pre-natal alcohol exposure) can createstructural and functional disruptionsthat lead to a wide range of physicaland mental illnesses later in adult life.1,6

A selective overview of this extensivescientific literature is provided below.

The association between ACE and un-healthy adult lifestyles has been welldocumented. Adolescents with a his-tory of multiple risk factors are morelikely to initiate drinking alcohol ata younger age and are more likely touse alcohol as a means of coping withstress than for social reasons.54 Theadoption of unhealthy lifestyles as acoping mechanism might also explainwhy higher ACE exposures are asso-ciated with tobacco use, illicit drugabuse, obesity, and promiscuity,55,56 aswell as why the risk of pathologicgambling is increased in adults whowere maltreated as children.57 Ado-lescents and adults who manifesthigher rates of risk-taking behaviorsare also more likely to have troublemaintaining supportive social net-works and are at higher risk of schoolfailure, gang membership, unemploy-ment, poverty, homelessness, violentcrime, incarceration, and becomingsingle parents. Furthermore, adultsin this high-risk group who becomeparents themselves are less likely tobe able to provide the kind of stableand supportive relationships that areneeded to protect their children fromthe damages of toxic stress. This in-tergenerational cycle of significantadversity, with its predictable repeti-tion of limited educational achieve-ment and poor health, is mediated, atleast in part, by the social inequalitiesand disrupted social networks thatcontribute to fragile families andparenting difficulties.7,58,59

The adoption of unhealthy lifestylesand associated exacerbation of so-cioeconomic inequalities are potent

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 1, January 2012 e237

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

by 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

risk factors for poor health. Up to 40%of early deaths have been estimatedto be the result of behavioral or life-style patterns,3 and 1 interpretation ofthe ACE study data is that toxic stressin childhood is associated with theadoption of unhealthy lifestyles as acoping mechanism.60 An additional 25%to 30% of early deaths are thought tobe attributable to either inadequaciesin medical care3 or socioeconomic cir-cumstances, many of which are knownto contribute to health care–relateddisparities.61–67

Beyond its strong association withlater risk-taking and generally un-healthy lifestyles, it is critically im-portant to underscore the extent towhich toxic stress in early childhoodhas also been shown to cause physi-ologic disruptions that persist intoadulthood and lead to frank disease,even in the absence of later health-threatening behaviors. For example,the biological manifestations of toxicstress can include alterations in im-mune function68 and measurable in-creases in inflammatory markers,69–72

which are known to be associatedwith poor health outcomes as diverseas cardiovascular disease,69,70,73 viralhepatitis,74 liver cancer,75 asthma,76

chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-ease,77 autoimmune diseases,78 poordental health,72 and depression.79–81

Thus, toxic stress in early childhoodnot only is a risk factor for later riskybehavior but also can be a directsource of biological injury or disrup-tion that may have lifelong conse-quences independent of whatevercircumstances might follow later inlife. In such cases, toxic stress can beviewed as the precipitant of a physio-logic memory or biological signaturethat confers lifelong risk well beyondits time of origin.38,42–44

Over and above its toll on individuals,it is also important to address theenormous social and economic costs

of toxic stress and its consequencesfor all of society. The multiple dimen-sions of these costs extend from dif-ferential levels of civic participationand their impacts on the quality ofcommunity life to the health and skillsof the nation’s workforce and itsability to participate successfully ina global economy. In the realm oflearning and behavior, economistsargue for early and sustained invest-ments in early care and educationprograms, particularly for childrenwhose parents have limited educationand low income, on the basis of per-suasive evidence from cost-benefitanalyses that reveal the costs of in-carceration and diminished economicproductivity associated with educa-tional failure.82–86 In view of the rela-tively scarce attention to healthoutcomes in these long-term follow-upstudies, the full return on investmentsthat reduce toxic stress in earlychildhood is likely to be much higher.Health care expenditures that arepaying for the consequences of un-healthy lifestyles (eg, obesity, tobacco,alcohol, and substance abuse) areenormous, and the costs of chronicdiseases that may have their originsearly in life include many conditionsthat consume a substantial percent-age of current state and federalbudgets. The potential savings inhealth care costs from even small,marginal reductions in the prevalenceof cardiovascular disease, hyperten-sion, diabetes, and depression are,therefore, likely to dwarf the consid-erable economic productivity andcriminal justice benefits that havebeen well documented for effectiveearly childhood interventions.

In summary, the EBD approach tochildhood adversity discussed in thisreport has 2 compelling implicationsfor a full, life span perspective onhealth promotion and disease pre-vention. First, it postulates that toxic

stress in early childhood plays animportant causal role in the inter-generational transmission of dispa-rities in educational achievement andhealth outcomes. Second, it under-scores the need for the entire medicalcommunity to focus more attention onthe roots of adult diseases that orig-inate during the prenatal and earlychildhood periods and to rethinkthe concept of preventive health carewithin a system that currently perpetu-ates a scientifically untenable wall be-tween pediatrics and internal medicine.

THE NEED FOR A NEW PEDIATRICPARADIGM TO PROMOTE HEALTHAND PREVENT DISEASE

In his 1966 Aldrich Award address,Dr Julius Richmond identified childdevelopment as the basic science ofpediatrics.87 It is now time to expandthe boundaries of that science by in-corporating more than 4 decades oftransformational research in neurosci-ence, molecular biology, and genomics,along with parallel advances in the be-havioral and social sciences (see Fig 1).This newly augmented, interdisciplinary,basic science of pediatrics offers apromising framework for a deeperunderstanding of the biology andecology of the developmental process.More importantly, it presents a com-pelling opportunity to leverage theserapidly advancing frontiers of knowl-edge to formulate more effective strat-egies to enhance lifelong outcomes inlearning, behavior, and health.

The time has come for a coordinatedeffort among basic scientists, pediat-ric subspecialists, and primary careclinicians to develop more effectivestrategies for addressing the origins ofsocial class, racial, and ethnic dis-parities in health and development.To this end, a unified, science-basedapproach to early childhood policyand practice across multiple sectors(including primary health care, early

e238 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICSby 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

care and education, and child welfare,among many others) could providea compelling framework for a new erain community-based investment inwhich coordinated efforts are drivenby a shared knowledge base ratherthan distracted by a diversity of tradi-tions, approaches, and funding streams.

Recognizing both the critical value andclear limitations of what can be ac-complished within the constraints ofan office visit, 21st century pediatricsis well positioned to serve as the pri-mary engine for a broader approachto health promotion and disease pre-vention that is guided by cutting-edgescience and expanded in scope be-yond individualized health care.88,89

The pediatric medical home of thefuture could offer more than the earlyidentification of concerns and timelyreferral to available programs, asenhanced collaboration between pedia-tricians and community-based agen-cies could be viewed as a vehiclefor testing promising new interven-tion strategies rather than simply

improving coordination among exist-ing services. With this goal in mind,science tells us that interventions thatstrengthen the capacities of familiesand communities to protect youngchildren from the disruptive effectsof toxic stress are likely to promotehealthier brain development and en-hanced physical and mental well-being. The EBD approach proposed inthis article is adapted from a science-based framework created by theCenter on the Developing Child atHarvard University to advance earlychildhood policies and programs thatsupport this vision (see Fig 2).1 Itsrationale, essential elements, and im-plications for pediatric practice aresummarized below.

Broadening the Framework forEarly Childhood Policy andPractice

Advances across the biological, be-havioral, and social sciences support2 clear and powerful messages forleaders who are searching for more

effective ways to improve the health ofthe nation.6 First, current health pro-motion and disease prevention poli-cies focused largely on adults wouldbe more effective if evidence-basedinvestments were also made tostrengthen the foundations of healthin the prenatal and early childhoodperiods. Second, significant reductionsin chronic disease could be achievedacross the life course by decreasingthe number and severity of adverseexperiences that threaten the well-being of young children and bystrengthening the protective relation-ships that help mitigate the harmfuleffects of toxic stress. The multipledomains that affect the biology ofhealth and development—includingthe foundations of healthy devel-opment, caregiver and communitycapacities, and public and private sec-tor policies and programs—providea rich array of targeted opportunitiesfor the introduction of innovativeinterventions, beginning in the earli-est years of life.1

FIGURE 2An ecobiodevelopmental framework for early childhood policies and programs. This was adapted from ref 1. See text for details.

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 1, January 2012 e239

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

by 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

The biology of health and develop-ment explains how experiences andenvironmental influences get underthe skin and interact with geneticpredispositions, which then result invarious combinations of physiologicadaptation and disruption that affectlifelong outcomes in learning, behavior,and both physical and mental well-being. These findings call for us toaugment adult-focused approaches tohealth promotion and disease preven-tion by addressing the early childhoodorigins of lifelong illness and disability.

The foundations of healthy devel-opment refers to 3 domains that es-tablish a context within which theearly roots of physical and mentalwell-being are nourished. These in-clude (1) a stable and responsiveenvironment of relationships, whichprovides young children with consis-tent, nurturing, and protective inter-actions with adults to enhance theirlearning and help them developadaptive capacities that promote well-regulated stress-response systems;(2) safe and supportive physical,chemical, and built environments,which provide physical and emotionalspaces that are free from toxins andfear, allow active exploration withoutsignificant risk of harm, and offersupport for families raising youngchildren; and (3) sound and appropri-ate nutrition, which includes health-promoting food intake and eatinghabits, beginning with the future moth-er’s preconception nutritional status.

Caregiver and community capaci-ties to promote health and preventdisease and disability refers to theability of family members, early child-hood program staff, and the social cap-ital provided through neighborhoods,voluntary associations, and the parents’workplaces to play a major supportiverole in strengthening the foundationsof child health. These capacities canbe grouped into 3 categories: (1) time

and commitment; (2) financial, psycho-logical, social, and institutional resour-ces; and (3) skills and knowledge.

Public and private sector policiesand programs can strengthen thefoundations of health through theirability to enhance the capacities ofcaregivers and communities in themultiple settings in which childrengrow up. Relevant policies includeboth legislative and administrativeactions that affect systems respon-sible for primary health care, publichealth, child care and early education,child welfare, early intervention, familyeconomic stability (including employ-ment support for parents and cashassistance), community development(including zoning regulations that in-fluence the availability of open spacesand sources of nutritious food), hous-ing, and environmental protection,among others. It is also important tounderscore the role that the privatesector can play in strengthening thecapacities of families to raise healthyand competent children, particularlythrough supportive workplace policies(such as paid parental leave, supportfor breastfeeding, and flexible workhours to attend school activities andmedical visits).

Defining a Distinctive Niche forPediatrics Among Multiple EarlyChildhood Disciplinesand Services

Notwithstanding the important goalof ensuring a medical home for allchildren, extensive evidence on thesocial determinants of health indicatesthat the reduction of disparities inphysical and mental well-being willdepend on more than access to high-quality medical care alone. Moreover,as noted previously, experience tellsus that continuing calls for enhancedcoordination of effort across servicesystems are unlikely to be sufficient ifthe systems are guided by different

values and bodies of knowledge andthe effects of their services are mod-est. With these caveats in mind,pediatricians are strategically situatedto mobilize the science of early child-hood development and its underly-ing neurobiology to stimulate freshthinking about both the scope of pri-mary health care and its relation toother programs serving young chil-dren and their families. Indeed, everysystem that touches the lives of chil-dren—as well as mothers before andduring pregnancy—offers an oppor-tunity to leverage this rapidly growingknowledge base to strengthen thefoundations and capacities that makelifelong healthy development possible.Toward this end, explicit investmentsin the early reduction of significantadversity are particularly likely togenerate positive returns.

The possibilities and limitations ofwell-child care within a multidimen-sional health system have been thefocus of a spirited and enduring dis-cussion within the pediatric com-munity.88,90,91 Over more than halfa century, this dialogue has focusedon the need for family-centered,community-based, culturally compe-tent care for children with develop-mental disabilities, behavior problems,and chronic health impairments, aswell as the need for a broader con-textual approach to the challenges ofproviding more effective interventionsfor children living under conditions ofpoverty, with or without the additionalcomplications of parental mental ill-ness, substance abuse, and exposureto violence.10 As the debate has con-tinued, the gap between the call forcomprehensive services and the re-alities of day-to-day practice has re-mained exceedingly difficult to reduce.Basic recommendations for routinedevelopmental screening and refer-rals to appropriate community-basedservices have been particularly difficult

e240 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICSby 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

to implement.92 The obstacles to prog-ress in this area have been formidableat both ends of the process—beginningwith the logistical and financial chal-lenges of conducting routine develop-mental screening in a busy officesetting and extending to significantlimitations in access to evidence-based services for children andfamilies who are identified as havingproblems that require intervention.

Despite long-standing calls for an ex-plicit, community-focused approach toprimary care, a recent national studyof pediatric practices identified per-sistent difficulties in achieving effec-tive linkages with community-basedresources as a major challenge.92 Aparallel survey of parents also notedthe limited communication that ex-ists between pediatric practices andcommunity-based services, such asSupplemental Nutrition Program forWomen, Infants, and Children; childcare providers; and schools.93 Per-haps most important, both groupsagreed that pediatricians cannot beexpected to meet all of a child’s needs.This challenge is further complicatedby the marked variability in qualityamong community-based services thatare available—ranging from evidence-based interventions that clearly im-prove child outcomes to programs thatappear to have only marginal effectsor no measurable impacts. Thus, al-though chronic difficulty in securingaccess to indicated services is animportant problem facing most prac-ticing pediatricians, the limited evi-dence of effectiveness for many of theoptions that are available (particu-larly in rural areas and many statesin which public investment in suchservices is more limited) presents aserious problem that must be acknowl-edged and afforded greater attention.

At this point in time, the design andsuccessful implementation of moreeffective models of health promotion

and disease prevention for childrenexperiencing significant adversity willrequire more than advocacy for in-creased funding. It will require a deepinvestment in the development, test-ing, continuous improvement, andbroad replication of innovative modelsof cross-disciplinary policy and pro-grammatic interventions that are guidedby scientific knowledge and led bypractitioners in the medical, educa-tional, and social services worlds whoare truly ready to work together (andto train the next generation of prac-titioners) in new ways.88,89 The sheernumber and complexity of under-addressed threats to child health thatare associated with toxic stressdemands bold, creative leadershipand the selection of strategic priori-ties for focused attention. To this end,science suggests that 2 areas areparticularly ripe for fresh thinking:the child welfare system and thetreatment of maternal depression.

For more than a century, child welfareservices have focused on physicalsafety, reduction of repeated injury,and child custody. Within this context,the role of the pediatrician is focusedlargely on the identification of sus-pected maltreatment and the docu-mentation and treatment of physicalinjuries. Advances in our understand-ing of the impact of toxic stress onlifelong health now underscore theneed for a broader pediatric approachto meet the needs of children who havebeen abused or neglected. In somecases, this could be provided withina medical home by skilled clinicianswith expertise in early childhoodmental health. In reality, however, themagnitude of needs in this area gen-erally exceeds the capacity of mostprimary care practice settings. A re-port from the Institute of Medicine andNational Research Council15 statedthat these needs could be addressedthrough regularized referrals from

the child welfare system to the earlyintervention system for children withdevelopmental delays or disabilities;subsequent federal reauthorizationsof the Keeping Children and FamiliesSafe Act and the Individuals with Dis-abilities Education Act (Part C) bothincluded requirements for establish-ing such linkages. The implementationof these federal requirements, how-ever, has moved slowly.

The growing availability of evidence-based interventions that have beenshown to improve outcomes for chil-dren in the child welfare system94

underscores the compelling need totransform “child protection” from itstraditional concern with physicalsafety and custody to a broader focuson the emotional, social, and cognitivecosts of maltreatment. The Centers forDisease Control and Prevention hastaken an important step forward bypromoting the prevention of childmaltreatment as a public health con-cern.95,96 The pediatric communitycould play a powerful role in leadingthe call for implementation of thenew requirement for linking childwelfare to early intervention programs,as well as bringing a strong, science-based perspective to the collaborativedevelopment and implementation ofmore effective intervention models.

The widespread absence of attentionto the mother-child relationship inthe treatment of depression in womenwith young children is another strikingexample of the gap between scienceand practice that could be reduced bytargeted pediatric advocacy.97 Exten-sive research has demonstrated theextent to which maternal depressioncompromises the contingent reciproc-ity between a mother and her youngchild that is essential for healthy cog-nitive, linguistic, social, and emotionaldevelopment.98 Despite that well-documented observation, the treat-ment of depression in women with

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 1, January 2012 e241

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

by 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

young children is typically viewed asan adult mental health service andrarely includes an explicit focus onthe mother-child relationship. This se-rious omission illustrates a lack ofunderstanding of the consequencesfor the developing brain of a youngchild when the required “serve andreturn” reciprocity of the mother-childrelationship is disrupted or incon-sistent. Consequently, and not sur-prisingly, abundant clinical researchindicates that the successful treat-ment of a mother’s depression doesnot generally translate into compara-ble recovery in her young child unlessthere is an explicit therapeutic focuson their dyadic relationship.98 Pedia-tricians are the natural authorities toshed light on this current deficiency inmental health service delivery. Advo-cating for payment mechanisms thatrequire (or provide incentives for) thecoordination of child and parent med-ical services (eg, through automaticcoverage for the parent-child dyadlinked to reimbursement for the treat-ment of maternal depression) offers 1promising strategy that AmericanAcademy of Pediatrics state chapterscould pursue. As noted previously,although some medical homes mayhave the expertise to provide thiskind of integrative treatment, mostpediatricians rely on the availabilityof other professionals with special-ized skills who are often difficult tofind. Whether such services are pro-vided within or connected to themedical home, it is clear that stan-dard pediatric practice must movebeyond screening for maternal de-pression and invest greater energy insecuring the provision of appropriateand effective treatment that meetsthe needs of both mothers and theiryoung children.

The targeted messages conveyed inthese 2 examples are illustrative ofthe kinds of specific actions that offer

promising new directions for the pe-diatric community beyond general callsfor comprehensive, family-centered,community-based services. Althoughthe practical constraints of office-basedpractice make it unlikely that manyprimary care clinicians will ever playa lead role in the treatment of childrenaffected by maltreatment or maternaldepression, pediatricians are still thebest positioned among all the pro-fessionals who care for young childrento provide the public voice and scientificleadership needed to catalyze the de-velopment and implementation of moreeffective strategies to reduce adver-sities that can lead to lifelong disparitiesin learning, behavior, and health.

A great deal has been said about howthe universality of pediatric primarycare makes it an ideal platform forcoordinating the services needed byvulnerable, young children and theirfamilies. In this respect, the medicalhome is strategically positioned toplay 2 important roles. The first is toensure that needs are identified, state-of-the-art management is provided asindicated, and credible evaluation isconducted to assess the effects of theservices that are being delivered. Thesecond and, ultimately, more trans-formational role is to mobilize the en-tire pediatric community (includingboth clinical specialists and basicscientists) to drive the design andtesting of much-needed, new, science-based interventions to reduce thesources and consequences of signifi-cant adversity in the lives of youngchildren.99 To this end, a powerful newrole awaits a new breed of pedia-tricians who are prepared to build onthe best of existing community-basedservices and to work closely withcreative leaders from a range of dis-ciplines and sectors to inform inno-vative approaches to health promotionand disease prevention that generategreater effects than existing efforts.

No other profession brings a compara-ble level of scientific expertise, profes-sional stature, and public trust—andnothing short of transformationalthinking beyond the hospital and of-fice settings is likely to create themagnitude of breakthroughs in healthpromotion that are needed to matchthe dramatic advances that are cur-rently emerging in the treatment ofdisease. This new direction must bepart of the new frontier in pediatrics—a frontier that brings cutting-edgescientific thinking to the multidimen-sional world of early childhood policyand practice for children who facesignificant adversity. Moving that fron-tier forward will benefit considerablyfrom pediatric leadership that pro-vides an intellectual and operationalbridge connecting the basic sciencesof neurobiology, molecular genetics,and developmental psychology to thebroad and diverse landscape of health,education, and human services.

SUMMARY

A vital and productive society with aprosperous and sustainable future isbuilt on a foundation of healthy childdevelopment. Health in the earliestyears—beginning with the futuremother’s well-being before she be-comes pregnant—lays the ground-work for a lifetime of the physical andmental vitality that is necessary fora strong workforce and responsibleparticipation in community life. Whendeveloping biological systems arestrengthened by positive early expe-riences, children are more likely tothrive and grow up to be healthy,contributing adults. Sound health inearly childhood provides a foundationfor the construction of sturdy brainarchitecture and the achievement ofa broad range of skills and learningcapacities. Together these constitutethe building blocks for a vital andsustainable society that invests in its

e242 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICSby 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

human capital and values the lives ofits children.

Advances in neuroscience, molecularbiology, and genomics have convergedon 3 compelling conclusions: (1) earlyexperiences are built into our bodies;(2) significant adversity can producephysiologic disruptions or biologicalmemories that undermine the devel-opment of the body’s stress responsesystems and affect the developingbrain, cardiovascular system, immunesystem, and metabolic regulatory con-trols; and (3) these physiologic dis-ruptions can persist far into adulthoodand lead to lifelong impairments inboth physical and mental health. Thistechnical report presents a frame-work for integrating recent advancesin our understanding of human de-velopment with a rich and growingbody of evidence regarding the dis-ruptive effects of childhood adversityand toxic stress. The EBD frameworkthat guides this report suggests thatmany adult diseases are, in fact, de-velopmental disorders that begin earlyin life. This framework indicates thatthe future of pediatrics lies in itsunique leadership position as a credi-ble and respected voice on behalf ofchildren, which provides a powerfulplatform for translating scientific ad-vances into more effective strategiesand creative interventions to reducethe early childhood adversities thatlead to lifelong impairments in learn-ing, behavior, and health.

CONCLUSIONS

1. Advances in a broad range ofinterdisciplinary fields, includingdevelopmental neuroscience, molec-ular biology, genomics, epigenetics,developmental psychology, epidemi-ology, and economics, are converg-ing on an integrated, basic scienceof pediatrics (see Fig 1).

2. Rooted in a deepening understand-ing of how brain architecture is

shaped by the interactive effectsof both genetic predisposition andenvironmental influence, and howits developing circuitry affects alifetime of learning, behavior, andhealth, advances in the biologicalsciences underscore the founda-tional importance of the earlyyears and support an EBD frame-work for understanding the evolu-tion of human health and diseaseacross the life span.

3. The biology of early childhood ad-versity reveals the important roleof toxic stress in disrupting devel-oping brain architecture and ad-versely affecting the concurrentdevelopment of other organ sys-tems and regulatory functions.

4. Toxic stress can lead to potentiallypermanent changes in learning(linguistic, cognitive, and social-emotional skills), behavior (adap-tive versus maladaptive responsesto future adversity), and physiology(a hyperresponsive or chronicallyactivated stress response) and cancause physiologic disruptions thatresult in higher levels of stress-related chronic diseases and in-crease the prevalence of unhealthylifestyles that lead to wideninghealth disparities.

5. The lifelong costs of childhoodtoxic stress are enormous, as man-ifested in adverse impacts on learn-ing, behavior, and health, andeffective early childhood interven-tions provide critical opportunitiesto prevent these undesirable out-comes and generate large eco-nomic returns for all of society.

6. The consequences of significant ad-versity early in life prompt an ur-gent call for innovative strategiesto reduce toxic stress within thecontext of a coordinated system ofpolicies and services guided by anintegrated science of early child-hood and early brain development.

7. An EBD framework, grounded in anintegrated basic science, providesa clear theory of change to helpleaders in policy and practice craftnew solutions to the challenges ofsocietal disparities in health, learn-ing, and behavior (see Fig 2).

8. Pediatrics provides a powerful yetunderused platform for translatingscientific advances into innovativeearly childhood policies, and prac-ticing pediatricians are ideally po-sitioned to participate “on theground” in the design, testing,and refinement of new models ofdisease prevention, health promo-tion, and developmental enhance-ment beginning in the earliestyears of life.

LEAD AUTHORSJack P. Shonkoff, MDAndrew S. Garner, MD, PhD

COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIALASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILYHEALTH, 2010–2011Benjamin S. Siegel, MD, ChairpersonMary I. Dobbins, MDMarian F. Earls, MDAndrew S. Garner, MD, PhDLaura McGuinn, MDJohn Pascoe, MD, MPHDavid L. Wood, MD

LIAISONSRobert T. Brown, PhD – Society of PediatricPsychologyTerry Carmichael, MSW – National Associationof Social WorkersMary Jo Kupst, PhD – Society of PediatricPsychologyD. Richard Martini, MD – American Academy ofChild and Adolescent PsychiatryMary Sheppard, MS, RN, PNP, BC – NationalAssociation of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners

CONSULTANTGeorge J. Cohen, MD

CONSULTANT AND LEAD AUTHORJack P. Shonkoff, MD

STAFFKaren S. Smith

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 1, January 2012 e243

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

by 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

COMMITTEE ON EARLY CHILDHOOD,ADOPTION, AND DEPENDENT CARE,2010–2011Pamela C. High, MD, ChairpersonElaine Donoghue, MDJill J. Fussell, MDMary Margaret Gleason, MDPaula K. Jaudes, MDVeronnie F. Jones, MDDavid M. Rubin, MDElaine E. Schulte, MD, MPH

STAFFMary Crane, PhD, LSW

SECTION ON DEVELOPMENTAL ANDBEHAVIORAL PEDIATRICS EXECUTIVECOMMITTEE, 2010–2011Michelle M. Macias, MD, Chairperson

Carolyn Bridgemohan, MDJill Fussell, MDEdward Goldson, MDLaura J. McGuinn, MDCarol Weitzman, MDLynn Mowbray Wegner, MD, Immediate PastChairperson

STAFFLinda B. Paul, MPH

REFERENCES

1. Center on the Developing Child at HarvardUniversity. The foundations of lifelonghealth are built in early childhood. Avail-able at: www.developingchild.harvard.edu.Accessed March 8, 2011

2. Knudsen EI, Heckman JJ, Cameron JL,Shonkoff JP. Economic, neurobiological,and behavioral perspectives on buildingAmerica’s future workforce. Proc Natl AcadSci U S A. 2006;103(27):10155–10162

3. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, KnickmanJR. The case for more active policy atten-tion to health promotion. Health Aff (Mill-wood). 2002;21(2):78–93

4. Schor EL, Abrams M, Shea K. Medicaid:health promotion and disease preventionfor school readiness. Health Aff (Millwood).2007;26(2):420–429

5. Wen CP, Tsai SP, Chung WS. A 10-year ex-perience with universal health insurancein Taiwan: measuring changes in healthand health disparity. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):258–267

6. Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuro-science, molecular biology, and the child-hood roots of health disparities: buildinga new framework for health promotion anddisease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301(21):2252–2259

7. Braveman P, Barclay C. Health disparities be-ginning in childhood: a life-course perspec-tive. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 3):S163–S175

8. Haggerty RJRK, Pless IB. Child Health andthe Community. New York, NY: John Wileyand Sons; 1975

9. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects ofChild and Family Health; American Acad-emy of Pediatrics. The new morbidityrevisited: a renewed commitment to thepsychosocial aspects of pediatric care.Pediatrics. 2001;108(5):1227–1230

10. Palfrey JS, Tonniges TF, Green M, RichmondJ. Introduction: addressing the millennialmorbidity—the context of community pe-diatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;115(suppl 4):1121–1123

11. Flores G, ; Committee On Pediatric Re-search. Technical report—racial and eth-nic disparities in the health and healthcare of children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4).Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/con-tent/full/125/4/e979

12. Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of HumanDevelopment: Experiments by Nature andDesign. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UniversityPress; 1979

13. Sameroff A. A unified theory of de-velopment: a dialectic integration of natureand nurture. Child Dev. 2010;81(1):6–22

14. Sameroff AJ, Chandler MJ. Reproductiverisk and the continuum of caretaking cau-sality. In: Horowitz FD, Hetherington M,Scarr-Salapatek S, Siegel G, eds. Review ofChild Development Research. Chicago, IL:University of Chicago; 1975:187–244

15. National Research Council, Institute ofMedicine, Committee on Integrating theScience of Early Childhood Development;Shonkoff JP, Phillips D, eds. From Neuronsto Neighborhoods: The Science of EarlyChildhood Development. Washington, DC:National Academies Press; 2000

16. Bronfenbrenner U. Making Human BeingsHuman: Bioecological Perspectives on Hu-man Development. Thousand Oaks, CA:Sage Publications; 2005

17. Shonkoff JP. Building a new bio-developmental framework to guide the fu-ture of early childhood policy. Child Dev.2010;81(1):357–367

18. Bagot RC, Meaney MJ. Epigenetics and thebiological basis of gene × environmentinteractions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psy-chiatry. 2010;49(8):752–771

19. National Scientific Council on the DevelopingChild. Early experiences can alter gene ex-pression and affect long-term development:working paper #10. Available at: www.developingchild.net. Accessed March 8, 2011

20. Meaney MJ. Epigenetics and the biologicaldefinition of gene × environment inter-actions. Child Dev. 2010;81(1):41–79

21. Meaney MJ, Szyf M. Environmental pro-gramming of stress responses through DNAmethylation: life at the interface betweena dynamic environment and a fixed genome.Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2005;7(2):103–123

22. Szyf M, McGowan P, Meaney MJ. The socialenvironment and the epigenome. EnvironMol Mutagen. 2008;49(1):46–60

23. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al.Relationship of childhood abuse andhousehold dysfunction to many of theleading causes of death in adults. The Ad-verse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study.Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258

24. Schweinhart LJ. Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age40. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press; 2005

25. Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ,et al. Effect of early childhood adversity onchild health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2006;160(12):1232–1238

26. Koenen KC, Moffitt TE, Poulton R, Martin J,Caspi A. Early childhood factors associatedwith the development of post-traumaticstress disorder: results from a longitudinalbirth cohort. Psychol Med. 2007;37(2):181–192

27. Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ,et al. Adverse childhood exposures andreported child health at age 12. AcadPediatr. 2009;9(3):150–156

28. Cottrell EC, Seckl JR. Prenatal stress, glu-cocorticoids and the programming of adultdisease. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:19

29. Darnaudéry M, Maccari S. Epigenetic pro-gramming of the stress response in maleand female rats by prenatal restraint stress.Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2008;57(2):571–585

30. Seckl JR, Meaney MJ. Glucocorticoid “pro-gramming” and PTSD risk. Ann N Y AcadSci. 2006;1071:351–378

31. Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M,Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM. Prenatal ex-posure to maternal depression, neonatalmethylation of human glucocorticoid re-ceptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol

e244 FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICSby 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

stress responses. Epigenetics. 2008;3(2):97–106

32. Brand SR, Engel SM, Canfield RL, Yehuda R.The effect of maternal PTSD following inutero trauma exposure on behavior andtemperament in the 9-month-old infant. AnnN Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:454–458

33. Murgatroyd C, Patchev AV, Wu Y, et al. Dy-namic DNA methylation programs persis-tent adverse effects of early-life stress. NatNeurosci. 2009;12(12):1559–1566

34. Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD.Lasting epigenetic influence of early-lifeadversity on the BDNF gene. Biol Psychiatry.2009;65(9):760–769

35. Szyf M. The early life environment and theepigenome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790(9):878–885

36. Compas BE. Psychobiological processes ofstress and coping: implications for resil-ience in children and adolescents—com-ments on the papers of Romeo & McEwenand Fisher et al. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:226–234

37. Gunnar M, Quevedo K. The neurobiology ofstress and development. Annu Rev Psychol.2007;58:145–173

38. McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology ofstress and adaptation: central role of thebrain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):873–904

39. McEwen BS. Stressed or stressed out: whatis the difference? J Psychiatry Neurosci.2005;30(5):315–318

40. McEwen BS, Seeman T. Protective anddamaging effects of mediators of stress.Elaborating and testing the concepts ofallostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y AcadSci. 1999;896:30–47

41. McEwen BS. Protective and damagingeffects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med.1998;338(3):171–179

42. Korte SM, Koolhaas JM, Wingfield JC, McE-wen BS. The Darwinian concept of stress:benefits of allostasis and costs of allostaticload and the trade-offs in health anddisease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(1):3–38

43. McEwen BS. Mood disorders and allostaticload. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):200–207

44. McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and dis-ease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N YAcad Sci. 1998;840:33–44

45. National Scientific Council on the Devel-oping Child. Excessive Stress Disrupts theArchitecture of the Developing Brain:Working Paper #3. Available at: developing-child.harvard.edu/resources/reports_and_working_papers/. Accessed March 8, 2011

46. McEwen BS. Protective and damagingeffects of stress mediators: central role of

the brain. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):367–381

47. McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Stress- andallostasis-induced brain plasticity. AnnuRev Med. 2011;62:431–445

48. National Scientific Council on the De-veloping Child. Persistent fear and anxietycan affect young children’s learning anddevelopment: working paper #9. Availableat: www.developingchild.net. AccessedMarch 8, 2011

49. Tottenham N, Hare TA, Quinn BT, et al. Pro-longed institutional rearing is associatedwith atypically large amygdala volume anddifficulties in emotion regulation. Dev Sci.2010;13(1):46–61

50. Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity tocontext: I. An evolutionary-developmentaltheory of the origins and functions ofstress reactivity. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17(2):271–301

51. Francis DD. Conceptualizing child healthdisparities: a role for developmental neu-rogenomics. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 3):S196–S202

52. Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostaticload biomarkers of chronic stress andimpact on health and cognition. NeurosciBiobehav Rev. 2010;35(1):2–16

53. McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of thebrain in stress and adaptation: links tosocioeconomic status, health, and disease.Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:190–222

54. Rothman EF, Edwards EM, Heeren T, HingsonRW. Adverse childhood experiences predictearlier age of drinking onset: results froma representative US sample of current orformer drinkers. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2).Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/2/e298

55. Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adversechildhood experiences and smoking duringadolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999;282(17):1652–1658

56. Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, et al. Theenduring effects of abuse and related ad-verse experiences in childhood. A conver-gence of evidence from neurobiology andepidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry ClinNeurosci. 2006;256(3):174–186

57. Scherrer JF, Xian H, Kapp JM, et al. Asso-ciation between exposure to childhood andlifetime traumatic events and lifetimepathological gambling in a twin cohort.J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(1):72–78

58. Wickrama KA, Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Jung T.Family antecedents and consequences oftrajectories of depressive symptoms fromadolescence to young adulthood: a lifecourse investigation. J Health Soc Behav.2008;49(4):468–483

59. Kahn RS, Brandt D, Whitaker RC. Combinedeffect of mothers’ and fathers’ mentalhealth symptoms on children’s behavioraland emotional well-being. Arch PediatrAdolesc Med. 2004;158(8):721–729

60. Felitti VJ. Adverse childhood experiencesand adult health. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(3):131–132

61. Althoff KN, Karpati A, Hero J, Matte TD.Secular changes in mortality disparities inNew York City: a reexamination. J UrbanHealth. 2009;86(5):729–744

62. Cheng TL, Jenkins RR. Health disparitiesacross the lifespan: where are the chil-dren? JAMA. 2009;301(23):2491–2492

63. DeVoe JE, Tillotson C, Wallace LS. Uninsuredchildren and adolescents with insuredparents. JAMA. 2008;300(16):1904–1913

64. Due P, Merlo J, Harel-Fisch Y, et al. Socio-economic inequality in exposure to bullyingduring adolescence: a comparative, cross-sectional, multilevel study in 35 countries.Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):907–914

65. Reid KW, Vittinghoff E, Kushel MB. Associa-tion between the level of housing in-stability, economic standing and healthcare access: a meta-regression. J HealthCare Poor Underserved. 2008;19(4):1212–1228

66. Stevens GD, Pickering TA, Seid M, Tsai KY.Disparities in the national prevalence ofa quality medical home for children withasthma. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(4):234–241

67. Williams DR, Sternthal M, Wright RJ. So-cial determinants: taking the social contextof asthma seriously. Pediatrics. 2009;123(suppl 3):S174–S184

68. Bierhaus A, Wolf J, Andrassy M, et al. Amechanism converting psychosocial stressinto mononuclear cell activation. Proc NatlAcad Sci U S A. 2003;100(4):1920–1925

69. Araújo JP, Lourenço P, Azevedo A, et al.Prognostic value of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in heart failure: a system-atic review. J Card Fail. 2009;15(3):256–266

70. Galkina E, Ley K. Immune and inflammatorymechanisms of atherosclerosis (*). AnnuRev Immunol. 2009;27:165–197

71. Miller GE, Chen E. Harsh family climate inearly life presages the emergence of aproinflammatory phenotype in adolescence.Psychol Sci. 2010;21(6):848–856

72. Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne BJ, et al. Associ-ation between children’s experience of so-cioeconomic disadvantage and adulthealth: a life-course study. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1640–1645

73. Ward JR, Wilson HL, Francis SE, CrossmanDC, Sabroe I. Translational mini-reviewseries on immunology of vascular dis-ease: inflammation, infections and Toll-like

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 1, January 2012 e245

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

by 1394751 on April 27, 2017Downloaded from

receptors in cardiovascular disease. ClinExp Immunol. 2009;156(3):386–394

74. Heydtmann M, Adams DH. Chemokines inthe immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C in-fection. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):676–688

75. Berasain C, Castillo J, Perugorria MJ,Latasa MU, Prieto J, Avila MA. Inflammationand liver cancer: new molecular links. AnnN Y Acad Sci. 2009;1155:206–221

76. Chen E, Miller GE. Stress and inflammationin exacerbations of asthma. Brain BehavImmun. 2007;21(8):993–999

77. Yao H, Rahman I. Current concepts on therole of inflammation in COPD and lungcancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9(4):375–383

78. Li M, Zhou Y, Feng G, Su SB. The critical roleof Toll-like receptor signaling pathways inthe induction and progression of autoim-mune diseases. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9(3):365–374

79. Danese A, Moffitt TE, Pariante CM, Ambler A,Poulton R, Caspi A. Elevated inflammationlevels in depressed adults with a history ofchildhood maltreatment. Arch Gen Psychi-atry. 2008;65(4):409–415

80. Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A,Poulton R. Childhood maltreatment pre-dicts adult inflammation in a life-coursestudy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(4):1319–1324

81. Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associa-tions of depression with C-reactive protein,IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. PsychosomMed. 2009;71(2):171–186

82. Cuhna F, Heckman JJ, Lochner LJ, MasterovDV. Interpreting the evidence on life cycleskill formation. In: Hanushek EA, Welch F, eds.Handbook of the Economics of Education.

Amsterdam, Netherlands: North-Holland; 2006:697–812

83. Heckman JJ, Stixrud J, Urzua S. The effectsof cognitive and non-cognitive abilities onlabor market outcomes and social behav-ior. J Labor Econ. 2006;24:411–482

84. Heckman JJ. Role of income and familyinfluence on child outcomes. Ann N Y AcadSci. 2008;1136:307–323

85. Heckman JJ. The case for investing in dis-advantaged young children. Available at:www.firstfocus.net/sites/default/files/r.2008-9.15.ff_.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2011

86. Heckman JJ, Masterov DV. The productivityargument for investing in young children.Available at: http://jenni.uchicago.edu/human-inequality/papers/Heckman_final_all_wp_2007-03-22c_jsb.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2011

87. Richmond JB. Child development: a basicscience for pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1967;39(5):649–658

88. Leslie LK, Slaw KM, Edwards A, Starmer AJ,Duby JC, ; Members of Vision of Pediatrics2020 Task Force. Peering into the future:pediatrics in a changing world. Pediatrics.2010;126(5):982–988

89. Starmer AJ, Duby JC, Slaw KM, Edwards A,Leslie LK, ; Members of Vision of Pediat-rics 2020 Task Force. Pediatrics in theyear 2020 and beyond: preparing forplausible futures. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):971–981

90. Halfon N, DuPlessis H, Inkelas M. Trans-forming the U.S. child health system. HealthAff (Millwood). 2007;26(2):315–330

91. Schor EL. The future pediatrician: pro-moting children’s health and development.J Pediatr. 2007;151(suppl 5):S11–S16

92. Tanner JL, Stein MT, Olson LM, Frintner MP,Radecki L. Reflections on well-child carepractice: a national study of pediatricclinicians. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):849–857

93. Radecki L, Olson LM, Frintner MP, Tanner JL,Stein MT. What do families want from well-child care? Including parents in the re-thinking discussion. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):858–865