MICHAEL TIPPETT c - solearabiantreesolearabiantree.net/namingofparts/pdf/tls/greatmangone7...As a ....

Transcript of MICHAEL TIPPETT c - solearabiantreesolearabiantree.net/namingofparts/pdf/tls/greatmangone7...As a ....

(c) 1965, Times NewspapersDoc ref: TLS-1965-0107 Date: January 7, 1965

liTERARY SUPPLEMENT . LONDON PRINTING HOUSE SQUARE

Thursday JaJiuary 7 1965

CENTRAL 2000

A GREAT MAN GONE A great w.piter and a great presence has go.ne feom us. Mr. T. S. EJiJot was full of years and honours and, in poetry, in drama, i n social and religious commentary, and in cri:l1cism had wriLten W'ha.t ihe wanted 00 write. He might almost be said. with his mend .and contemporary, Mr. Ezra Pound, to have invented or oreated the "modern movement" .in An-gioAmerican poe::ry. He can be said, also, in a few seminal essays to have laid the foundations 'Of <'llhe view 'Of llhe English poetic tradition which has dominated universi.Ly teaching in En,gl.and and the United States Qver tOlC past thinly 'Or for-IY years. Dr. F. R. Lcavis's Revaluation, fer instance, owes very much, in its handling 'Of tihe ·ideas 'Of tradition and of tJhc .. Hoe 'Of wit ", to a few early essays of Mr. Eliot's. A good deaJ 'Of ourrenl Cl'iticism of pooLry reads like f'Oomotes 'to Mr. Eliot or expansions and illustrations of ideas which he condensed into a phrase. In his .socia l and reHgious writings he deliberate· Iy took up what he lhollght of as a stern and unpopular point of view, and certainly a conservative point of view. Yet, as a publisher. nobody gave more encouragement in the 19305 th an Mr, Eliot to young poets of the Left ~ikc Mr. Auden and Mr, Spender a nd Louis Mac Neice; and in trhe 1950s radical critics of litera ture and society, like Mr. Hoggart and Mr. Raymond Wi·~iams. saw that Mr. ELiot's notions of culture as rooted in communal habit and prejudice suited them far better 4lhan liberal individua lism. As a . dramatist, tbough he failed to establish a new tradition of verse drama. and though he seemed to some critics to be diluting his purely poetic gifts, he cstab· lished. late in life, a contact w!:h a far wider audience t:han had been won by (tis poems 01' his criLic.i.sms: and he did this without compromisin.g his digniliY, bltlrring the edge of his ideas, or showjng any fumbling or hesitation in a medium that was new to him. A cef'ltain openness, a sympathy, a readiness to Jearn Wa5

the obverse of waat appeared the rigid, Uhe dogmatic, and perhaps intolerant core of his attitudes.

Mr. Eliot was bolth 13. SJby and a proud man, and some cri Lics have thousfht t.hat his insistence .in early cdwcal eS53ys on the imperstonGlity of poetic art, 'On the irrelevance of the roman·tic ideal of the poem as spiriLua'l autobiogr·aphy and selfreveila.(ion, 'On the sharp d:istinction between the man who sutTers and the artist Who creatcs, was pa.rtly 3-

defensive manoeuvre, sprin.~i ng from an awareness of bow tbo-rou0h·ly, even in :his earlies.t work, he had unlocked his heart. From the same shyness may have sprung his dislike, up to Al'/J Wed,lesday, of appearing in person as (·he .. I" of one oflhis poems. CortainJy it is easy now to read tlhe whole sequence of his serious and major non-dramatic poems oaS' a kind of spiritual autobio· gra)lh.y, the earlies-t poems presentin.g sometimes fl ippantly a mood of scepticism and malaise deepen.ing into one of disgust and horror, The Waste Land and The Hollow Men mark.ing a poinJ. of spidtual ~risis, and Ash Wedllesday and Four Quartets recording a process o.f acceptance of rel·i@ious belief and sltow and painful disciplinin.g of the ,elf. Yet t-he very painfulness of this p rocess of self- revelation led Mr. Eiot, .in his later years, to the drnm:l. His dramas lioti.l:l reveal him, but with an indirectness w.bkh was congellJal to his tempe·rament.

He was a great critic. but his great_ ness was perhaps flawed by a certain evasiveness. He did not himself either write or re-read his cdtical prose with

THE TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT THURSDAY JANUARY 7 1965

. pleasure and, though it is both packed and gracef.ul, it is peculiarly elliptical or abrupt in the movement of its thought. Of two great Tory and C hristian poets and cri.tics whom he loved, Mr. Eliot resembled Dry~ den in Ule apparently casual and informal movement of his thought rather Ulan Dr. J ohnson in his orderly argumentation and combative briskness. He perhaps also resembled D ryden more as a person. Dryden, according to Congreve, had to be drawn out, and ha·ted to appear to intrude; nobody could be kinder and more patient than Mr. Eliot with young poets Who wanted to consult rum, but the coo,rteous reserve of his manner had something faintly deterrent about 31, and his close fr iendships were perhaps few. He lent himself generously to official social occasio ns, but had not the gift of easy and informal sociability. His conversation was slow, pondered, lapida ry, a conversation of hints and implications. Some o.f t hese personal characteristics come out in his criti. cat prose, w here he always preferred lIhe suggestive phrase or aphorism to the labor~ously explicit argument; where Mr. Eliot was laboriously explicit. usually, W1lS in defining wrhat he did 1101 want to say. H is earl~er, but not .so much his later, essays were enl'lVe·ned by touches of pert and waspish wit j even in the la4er essays, written as lecture scripts where the eartier o nes had been wr.itlen mainly as review-articles a ce rtain demure misc hievousn~ss oftcn lurks not very far unde r Ille srave surf-ace. In his cdt.ical prose, as in h is poetry, he appears as d,is· tinctly formidable by what hc holds in reserve.

Important though he was as a c ritic, social thinker, and drama tist, it is as a poet that Mr. Eliot made his deepest mark on his age. Probably 110 poem in literary history, certainly no poem of similar length, has been translated into so many languages as The Waste Land in the au thor's l ifet ime, or subjected to such exhaustive commentary. ]t is not Mr. Eliot's greatest poem. it is perhaps in some ways a flawed poem, for it s till arouses as much argument as Shakespeare's IImn/et; but it is Mr. Eliot's most interesting poem, as HamIel was Shakespeare's most interest ing play. Mr. Eliot's poems up to The Waste Land and through the convalescent whimperings oC The Hollow Men are poems of wbat he called in his las t and greatest long poem, Lillie Gidding, " the exasperated spirit ", poems of the wounded soul. Their vision o f the ":orld combines horror, bleak compassion, touches of hysterical gaiety, with brief moments of extraoruinary tenderness. They contained the voices of many enacted selves, were essentially dramatic. These early poems were the work of a writer almost torn to pieces by the incoherence and brutality of experience, the impossibil it y of knowJedge, and yet with rhe phra5es and the cadences of the great atlirmatjve poetry of the past echoing. often apparen tly meaninglessly, jarringly, or threaten ingly in his head. U the vision was new, so was the technique. The staid English iambic line was transformed by jazz syncopation or by an extraordinary mimicry of the rhetoric of Jacobean drama. ]n the diction authentic slang altern ated wi th scholarly pastiche. Some surly critics, like Richard Aldington.. have sugges ted that all Mr. Eliot's best Jines were written by other people. And yet, as in the first few lines of Al·/J Wednesday, where M,r. Bliot plays for three or four Hnes with a sl,ightly mistranSilrated phrase from Guido Cavakanti to lead up to a sHgh tl y misquoted line from S'hakespeare's sonnets, the real borrowed gold is transmuted into a new,

-equa"y real Ei.io t·ic gold. The reader wbo -s'pots the a,liIusions is given the cue that this long poem is to be about the ren uncia· lio n of earthly love and ambition, a renunciartion in some ways bitter and reluctant; and, here as e lsewhere, Mr. Eliot imposes even on the great poets whom he robs a rhythm, harsh, hesitant, subtly nuanced. abruptly changing in pacc. which is entirely his own.

Mr. Eliot's speak ing vcice, at least in his late( years, had a dry, creaking timbre, a faintly parsonical note. It belonged nowhere particularly, except in Mr. Eliot's moubh, was not distinctively American or typically English. Yet h is recordings of his poems catch perfectly the pauses, the hurryings and the slackenings, the premeditated or inspired shifts of pace and tone in which so much of bis art of composition lay. The dry sadness of that speaking voice, proud, resigned. shrewd, reverent, formally civil or subtly ironical, is built into the substan<:e of the poems. Mr. Eliot had a revolutionary effect on the gene ral techniques of AngloAmerican poetry, yet be leaves behind him nothing that could be called "ine sOOocl o'f Eliot": like Milton , whom he attacked early and later cautiously praised, be was too individual both in his art and in his sense of life to be very effectively i mitated, except by parodists like Mr, H enry Reed.

Of the greatn~s of Mr. Eliot's poetry, it might be fur ther said that it lies in concentration, in immediacy, Qnd in depvh, ratoher tban in range, He ha s nothing like tbe human SJWeep and Lhe buoyancy of his great o ldor contemporary, Yeats. He was interested, as he said himself, in tbe !ho rI'O r, boredom, and gt'Ory of the world rather than its bea uty, tlbough certain. ima·ges of beauty, hyacjnJhs. a woman's hair, and later Landscape jlll·ages from Ibis boyish memories of America, the rank ailan4.hus by the April docryard in St. Louiso,lihe pine-Irees.and tbe mists and the gmnite shores of Cape Ann, rec-ur Ih auntin,@ly, the landscape images especially in nis late'r and avowedly Chri stian works. But it was bis gre.at power alw..ty.s to take life and (he so ul and its destination with profound seriousness, and to waigh, with a troubled heart, intimations of ,irnm'Ortality:

Yet the enehainment of past and fu ture Woven in Ihe weakness of Ihe ehangina

body. Protects mankind (rom heaven and

damnation Which flesh cannot endure.

One more thi ng should be s·a·id. It is sometimes f'Orgotten how young he was, how new and raw to the complications of human experience, when he began to write great poems; no poet of o ur century means more to the young who are lucky enough to come on him in thei r late teens. He remained to the end exposed to the shocks of experience like a young man: .. Old men shOUld be ex~ plorers." For many readers Mr. EI·jot's doo1.h will be ~ike the deat'h of part of themselves, the death of the shock and exh ilaration of cne's first insigbt in to tbe gulfs and heights, the bewildering threats and promi5es, of life; and it ma y be Mr. Eliot's youngest and newest readers who will feel tbis most acutely,

Letters to the Editor A REAL DEEP SPARKLE Sir,-I haVe not read the article by

Mr. Pla'nte on which you comment in your leader ,. A Real Deep Sparkle" (TLS, December 30), but I am dismayed by your failure to s}'mpathize with what seems to be a genuine attempt to sort out the dilemma of creative people in the business world.

The front pa&:e article of you r issue of December 17. .. Pop Goes the Artist", remi nds us how few writers can make a living b~' books alone: I have mysoU publi shed two novels., but would starve if I relied on them for my bread· and-bUller, let alone jam. So I write brochures, ca talogues. articles for trade journals-in short. advertisin&: work of every kind. I recognize tllat such writing is generally insianificant at best, positively offensive at worst (even apart from any moral issues); a~1 the more reason, then, for you to encourage those, like Mr. Plante, who arc concerned a t this situation and trying to better it.

Li-ke M r. Plante. I try to do a good job for my commercial clients, \Wjich means being as "creative" as I know how. I cannot suppose you will disapprove of such attemPts to raise stan· dards, even on l'he outermost frontiers of 1iterature. Nor ;tre You likely to deny that much which passcs fo r literature is in fact less ima ginative and I~s creative t'han much whic h is produced for purposes of commerce.

11 is not an easy feat, to stand with one foot in literat ure and ano't·her in business: but many thousands of creative peop.)o In phrase which is not the sYnOD)"lD for artist which rou try 10

make it) have to learn it. Jam '-trnteful to Mr. Plante for his atttempt to be

~~!pf~1 ~ ~:siti~~~oa~e: st~a~~~~,:o~~ he!pful, Ihave chosen to adopt so un'hel;pfu·1 a.n attitude.

HILARY EVANS. 23 The Keep. BJackheath London

S.E.3. .,

Sir,-Your editorial on my article in the CUfTC!lt .4ssue of the AdlierOsillR Qllarterly md,lcates ~hat you ha ve rmsscd tthe whole pomt for indeed 1 was writing about the problems of creativity as appLied to bus.ineu as distinct f'rom the fine arts.

Even so t.tlere is not.ning new in the fact that writers and artists have t o con-tond wjih t,he disciplines imposed upon ,·hem by their patrons. It has

~~a~~~sW:{ ~~::~h c~~~~fca'~~ -PTObaWy started by . .

vision re on y bcgin

nin&: to make themselves evident. The pre..~sure of time alone is such liS to make priorities viotaJ.

You can elect to disapprove of the rn.~mufacturer's world .if you will. An economy based on a non-commercial. non-materialistic society may be desirable, but so far tlhcrre is no sign that moo have been able to devise one, or that w.riters a nd artists can th.ri.ve in one. In the meantime it is of no help just to deplore t.he li mes we Jive in.

There a'l'e man.y ()Cople with considerable creative ability who are being discouraged forom trYing tJheir hand at somethi,"~ they might well find rewardina because of lobe aU.ilude expressed in your comments. \Ii1bjch are not on ly oul of touch with t·ho needs of indus: ry, but a lso out of touch with the ueeds of many aa1Jsts and writers.

GEORGE PLANTE. Studio House, Tempiewood Ave nue,

London, N.W.3.

SHAKESPEARE AND THE "SCHOOL OF KNIGHT" Sir,-I regret that y.:lur reviewer on

December 24 of Shakespeare alfd Chris· riull Doctrine <has followed oChers in failing to pillory Mr. Frye's misrcpre· sentations. T<he c.harges 3evel\ed by Mr. Frye at me and what he calls my .. sehoot" (such as medievalizing Shakespeare, usina the supposed though t-schemes of ,his time as a tool of c.:lmmentary, sending his tragic heroes to Hell or Heave," alIter tJhe play) are precisely those which 1 have from the fi rst, as in the concluding sentence of My/II and Miracle, repudiated, Those interested might burn to the essay .. Some Notable Fallacies II in The SOl'creiCII Flower~ to the 1951 Preface to rhe Imperial Theme; t.., the 1953 Preface to Tile Shakespearl(llil T('mpesl; and to The Crown 0/ Lile, pp. 22. 35, 96-7, 128, 227, 251 (" without theolo~y "),253, 277,297,314·15.317.

Mr, Frye rcorers (0 tl+'O only of my seven book.s on Shakespeare and from these he misquotes. My remark at one poin.t that" the Oh,rist sacrifice can, if we like, be seen as central" is repeated, deliberateJ.y, with d'Ots replacin&: the reservation ., if we like" in suoh a way as to bu.ild up the ~rina.1 emphasis Which he wishes to impute; and when. foll.owing Shakespeare's own two comparisons of Timon and Ch ris.t, I once SUggested I·hat TImon's servants, in one- scene, were" as disciples of the Christ ", Mr. Fr}'c omits-w:tlh out dots - -the word "as" so as to turn a comparison into an identificuLion.

A detailed cxpomre of Mr. Frye's quite stag~eri ng blunders is to appear shortly in £\"JaYJ' in Critici,llII. I have ",!:ready asked, ~n Tlie New Stale.mum on August 21, 1964, and 1 now usk a~ain

~~~f~rs/bo~:o~~~ihJ~~~~is crude That the nature of the subtleties, to

~'h ich -l have given attention at every turn in my own wri tings, of Shakespeare's dramatic and Nietzschean divergencies from the med:eva·l trad ition is bc}'ond rhe percipience of most of my readers the reviews of Mr. Fo'e's book make abundantly clear; and where understand in: is so limited his falsifications are likely to prove per.n:ciolls. As for my supposed" school ", I k.now of none. If my li fc's work is 10 be tied to aH the critic-,iI or doctrina·1 groups that have used i~, 1 have- whatevc r their merits or demerits, and I wish to attack none of them-4'lo ;csource but, foJiowing Byron in his Journal of March 17, I~J4, me reply, "I'U not maroh through Coventry with them, that', fla:t",

G. WILSON KN·IG HT. Exeter.

MR. MACDIARMID AND DR. GRIEVE

Sir,- ln my piece on two recent books

i)be:~b~/'30~urhher:-':~P~h~:de~~:SSi would like to correct. First, through· oot the piece 1 misspell M.r. Kenneth BUlhla)"s name as Buthlcy. ~OI1dly, in t-he 19305 Mr. MacDiarmid did nol receive a Civil U~~ Pension (thai came Jater) but a Grant fr-om the Royal Uter· ary Fund. Thirdl y, th,fCC words were omitted from my last verse quotat ion from Mr. MacDiarmid. which should have read There are plenty of ruined builliings in

the world but no ruined ston es ...

J apoloi:;ize to all concerned, and ca n only plead in extenuation tha t I had to telephone corrections al rather ~hort notice durini: the O1ristmas rush,

YOUR REVIEWER.

(Other fellers. notably 0 11 .. AlUm:hism ", are 011 page 14.)

caaaaaaa c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c a a a a a c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c e e c e e e e e e e c e e e e e e e e e e

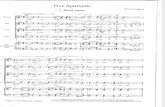

MICHAEL TIPPETT

A SYMPOSIUM ON HIS SIXTIETH BIRTHDAY

Edited by IAN KEMP A birthday symposium by a group of the composer's friends and admirers. It comprises an anthology of diverse and diverting tribute~. with a section of analytical essays on Mr. Tippett's music, U ThCf mOst s uccessful symposium I know about an individual composer."EDWARD GREENFIELD.

GUA'RDIAN. With 8 pages of photographs, 8 of drawings and 78 music examples. SO/-

The Presence of Spain

JAMES MORRIS " He Joves the whole phenomenon that is Spain, and conveys incomparably the beauty of its landscape and buildings and human gesture~. The book is beautifully produced, the photographs numerous and excellent, occasionally sublime."-THE TlMI!S EDUCATIONAL SUPl'LEMENT.

With over 100 photographs by EVELYN HOFER. 84/.

The Call of the Tiger

M. M. ISMAIL An absorbing account of the hazards and pleasures of biggame hunting, It is at the same time a record of jungle wild life rapidly disappearing from many parts of India. 18/-

The Indo-China War 1945-54 EDGAR O'BALLANCE

Major O'Ballancc's study in guerrilla warfare analyses French and Viet Minh suc~ cesses and failures, from the return of lhe French army in 1945 'to the fall of Dienbienphu. With 19 photc-graphs and 10 maps. 35/·

Mathematics and Logic In History and in

Contemporary Thought

EITORE CARRUCCIO· A clear and intell igible account of the history of pure mathematics that relates it to the development of logic in general and mathematical logic in particular. 63/·

The Syndic C. M. KORNBLUTH

Cyril Kornbluth, who died in 1958, is recogn ized ns ( ne of the masters of modern science fiction. Tlte SYlldic is now published in this country for the first time. 18/.

Wind versus Polygamy OBI B. EGBUNA

.. Lively dialogue, excellent social detail and a neat , witty plot make this an original shortnovel. "-sPECTAToR.16/-

e eee