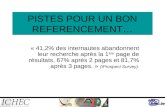

Metz for Tomarrow

description

Transcript of Metz for Tomarrow

Christian Metz’s “Identification, Mirror” and “The Passion for Perceiving”:

A Brief Overview

In his essay “Identification, Mirror” and “The passion for Perceiving”, an

excerpt from the book The Imaginary Signifier, Christian Metz draws on the

works of spectatorship theorists such as Jean-Louis Baudry and expands the

notion of the cinematic apparatus to encompass a more general view of the

“imaginary signifier” and its institutional context. Metz attempts, through the

use of psychoanalysis, to discover an original grounding event that would

systematically explain the nature of the film spectator. Although Baudry drew

some ideas from the thought of psychoanalysis, Metz goes much further in

incorporating psychoanalytic notions into his theory of film spectatorship.

Metz agrees with Baudry that there are always certain structures that go into

the constitution and pleasure of the cinematic spectator. Both writers agree

that the spectator is constructed and positioned by the cinematic apparatus.

For Baudry it was the cinematic apparatus as a technical instrument, for Metz

it is the more general notion of the cinematic institution. For Metz the

interlocking mechanisms of cinema institutions (production, exhibition, the

development of classical Hollywood cinema) work to fashion individuals to

conditions of fantasy, desire, and pleasure and it makes moviegoers out of

them. This intersection of individual and institution is evident when Metz

speaks of a deep kinship between the psychic situation of the spectator and

the financial and industrial mechanisms of the cinema. Not only is an

“impression of reality” created, as Baudry would say, but a “deep psychic

gratification” or pleasure is produced that goes beyond mere enjoyment and

touches deep unconscious material in the spectator. As Metz has pointed out

Hollywood is about the creation of “good objects” in the psychoanalytic sense

of the phrase. “Good objects” or rather films that produce pleasure and

compel the spectator to return to the cinema again and again. Thus for Metz

spectator is never a flesh and blood viewer but S/he is an artificial construct, a

site of specific effects produced by cinematic apparatus.

One of the primary psychic structures involved in cinematic spectatorship is

the process of denial or disavowal. Metz believes that the film spectator exists

in a state of hallucination and regression; the spectator believes, on some

level, that the events and characters on the screen are real even though they

are not. The film viewer suspends his or her disbelief even though he or she

also knows that it is only a movie. For Metz, this splitting of belief into two

contradictory states was based on a more primal disavowal, more specifically

the disavowal associated with fetishism and castration anxiety in the child.

According to Freud, the mechanism of disavowal is the mode of defense

whereby the subject refuses to acknowledge the reality of a traumatic event or

perception. Disavowal is founded on the male child’s persistent belief in the

phallus of the mother despite the anxiety producing image of her lack of a

penis i.e. the reality of castration. ( In the adult, Freud believed, a fetishism,

such as the sexual need for a particular object like a shoe, is a way of denying

the anxiety produced by the thought of the castration of the mother by

substituting an object for the castrated phallus.) As Metz states in The

Imaginary Signifier:

“In the face of this unveiling of a lack (we are already close to

the cinematic signifier), the child… will have to double up its

belief (another cinematic characteristic) and from then on

forever hold two contradictory opinions… In other words, it will,

perhaps definitively, retain its former belief beneath the new

ones, but it will also hold to its new perceptual observation

while disavowing it on another level. Thus establishing the

lasting matrix, the affective prototype of all the splittings of

disbelief” (68).

For Metz the film spectator’s ability to hold “two contradictory opinions” is

rooted in the early experience of the child’s disavowal of castration by

maintaining a belief in the maternal phallus. Metz maintains this is the root or

“matrix” of the ability to psychically hold two different emotional experiences

which the cinematic apparatus then activates. The spectator is split into two

different states; there is an incredulous spectator that knows the events on the

screen are merely projected light and are fictional (that is, there is in the

spectator a deeper psychic layer that perceives that the mother doesn’t

possess a penis and therefore is castrated) and a credulous spectator that

believes the events and characters on the screen are real ( that is, there is in

the spectator a refusal to believe that the mother is castrated and a desire to

believe she has a penis). For Metz, fundamental to the film-viewing situation is

the continual back and forth splitting of consciousness and belief based on this

primary fetishistic disavowal. (It is fetishistic because it allows simultaneous

elaboration of two contradictory meanings and experiences.) The

consciousness of the spectator is divided; a “no” to reality and a “yes” to the

cinematic illusion. The cinematic experience is made possible by and

recapitulates for the film spectator the earlier unconscious experience.

Another important structure of the spectator for Metz is identification as

primary cinematic identification. There is, at a fundamental level, a

displacement of the spectator’s perceptual system by the technical and

institutional apparatus of the cinema; Metz sees this as identification with the

act of looking or perceiving itself. As Metz states:

“I am all-perceiving… (T)he spectator identifies with himself,

with himself as a pure act of perception (as wakefulness,

alertness): as condition of possibility of the perceived and

hence as a kind of transcendental subject, anterior to every

there is”( 48).

Metz considers this type of identification primary because it makes all other

identifications, such as identifications with characters, emotions, and events,

possible. This primary identification is constructed and directed by the camera

and its intermediate relay the projector. The spectator’s consciousness merges

or becomes the perception of the camera/projector. For Metz this type of

identification of the spectator is not a kind of empathy found in the way

spectators feel and share the feelings of the characters on the screen, rather it

is the act by which the spectator sees (and believes) what the

camera/projector sees. The spectator perceives from the position of the

camera/projector. For Metz, and for Baudry, the spectator identifies not so

much with what is represented, that is the content of the film, but with what

creates the film; the cinematic apparatus.

Metz, in a more psychoanalytic turn, relates this experience of primary

identification with what psychoanalysts have termed the “mirror phase”. For

psychoanalysts like Jacque Lacan one of the formative psychic processes of

human beings is the mirror phase; the infant’s ego or self emerges through the

infant’s identification with an image of its own body in a mirror (or could we

say also with the mother’s face, or any surface or “other” that projects back to

the infant). Around six to eighteen months, when the child perceives its image

in the mirror, it mistakes or misrecognizes this unified, coherent image for

itself. A self-image that is superior or idealized because of its apparent

coherency and unity; the actual child is really quite uncoordinated and

fragmentary in its movements and abilities. The child then identifies with this

image and finds, according to Lacan, satisfaction in its unity, a unity which the

child cannot experience in its own body. The child not only identifies with this

image of itself but begins to perceive itself through the otherness of this

image, i.e. it can see itself as something that is other, as other people would

see the child. What ties this process to the cinema for Metz is that it takes

place with visual images; the child sees itself as an image which is distanced

and objectified and identifies with it. For Metz there is a primary similarity

between the infant in front of the mirror and the spectator sitting in front of

the screen. Both are identifying with and fascinated by images and

furthermore images which are ideals. The early process of the mirror phase

through which the child constructs an ego by identifying and absorbing an

image in a mirror underpins the later experience of the film spectator that

identifies with the idealized images of the projector on the screen. However

Metz also distinguishes a difference in film spectatorship from the Lacanian

mirror stage. For Lacan the beginning of the constitution of the subject in the

mirror stage occurs because it is a self-image the infant perceives in the mirror;

Metz observes that in the act of watching a film we are profoundly absent

from the images on the screen. Although we feel as though our perception is

ubiquitous within the world of the film, a surveillance of all things within it, we

can never see ourselves directly within this world.

Source:

http://pietothemediaecologist.wordpress.com/2010/04/14/christian-metz-

and-the-imaginary-signifier/