Metamorphic Urbanity

-

Upload

shantesh-kelvekar -

Category

Documents

-

view

241 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Metamorphic Urbanity

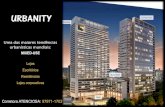

Metamorphic Urbanity -a [meta]physical transition

Abstract

Cities in the present scenario are both shrinking and expanding. Shrinking, as the

virtual becomes more realistic and provides a platform for social, communal and

economic activities; eliminating the need for physical space. And at the same time

expanding because of the shear need to cater to the growing urban population, by

providing new physical infrastructures.

Due to this immense need for growth the pressure is increasing tremendously on the

planning organisations. The transition in the current scenario is drastic and the

conventional planning methodologies seem to operate less efficiently. As Koolhaas

states (with respect to architecture) that there is a discrepancy or time-lag between

the acceleration of culture and the continuing slowness in architecture1, the case

becomes intensely factual with respect to the current urban growth where the

economic and social conditions are altering rapidly.

Growth is evident, curbing the growth is not a possibility; in such a dialectic situation

going anti-urban would be demanding going against the system! But, following the

system with traditional models of urbanism is also ridiculous. Between these conflicts

lies the solution of our future urban; the investigation aims at delivering a model

which challenges the conditions and emerges from it as a promising methodology.

References 1 –Koolhaas, Rem (2004), in an interview in IconEye

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

2

Introduction

The Asian market is booming up rapidly and one can clearly see the reflection of it in the

growing economic giants like China and India. China in the recent past has become a

humungous economic hub for the world market. The neo-liberal policies on international

trade during 1980s opened up the whole world to transformative market and financial forces.

In this clinch China also opened up, albeit under strict state supervision, to foreign trade and

foreign investment, thus ending China’s isolation from the world market1. As a response,

sudden growth of economy was evident in South-East China because of the proximity of a

long coastline which led to international trade routes. This has led to certain alterations

within the urban cores of this region closer to Shanghai, which raises questions of concern

with respect to consequences in urban development. The primary changes occurred in the

last twenty years is a thick migration from rural to urban; this has led to an unimaginable

growth of the cities in this region. In some of the cases the bureaucratic boundaries of these

cities have expanded up to more than two folds.

Taking the case of China and its stance on rapid urbanisation the intent of this paper is to

enquire the methodologies applied in the process of its recent urban growth and its

ambitious proposals in the near future.

The implied prototypical methodologies of planning for urbanisation in China fail to function

as desired, leading to stagnation in moulding the urban. There is a clear need for an

adaptive practice, which manoeuvres itself according to the changing conditions and yet

blends perfectly with the context. Equally, the methodology should be proficient to imply on

multiple scenarios, as there is a need for an urgent growth. Existing cities are expanding,

new cities are proposed to distribute the pressure of the existing cities; the approach should

not be the solution itself, rather it should become a proficient situation to start a new

acceptable disturbance within the existing which attempts to make the entire system

autonomous.

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

3

Conditions

The world is transforming rapidly. Probably alterations and changes occurred in lifestyles,

cultures and societies in the last two centuries could be accounted more than it has ever

occurred. One of the major reasons for this drastic change is the advent of the new

technological systems and acceptance of newer scientific methodologies. As Guattari states,

“The earth is undergoing a period of intense techno-scientific transformations. If no remedy

is found, the ecological disequilibrium this has generated will ultimately threaten the

continuation of life on the planet’s surface”2, the situation although not so intense at present,

raises a question over the rapid urbanisation happening around; in this case China.

China is determined to create 400 cities by 2020; the attitude is bold but the impact is an

outcome of a very shallow vision. In the urge of delivering cities at a faster rate planners are

giving a rhetoric output. The methodology implied seems easier to construct but is leading to

one of the conditions already criticised in the post industrial cities, the sprawl.

Reasoning the approach

As Koolhaas states in his essay ‘The Generic City’:

Figure 1: Potential zones of urbanisation in China (Source: GO-West)

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

4

“The Generic City is on its way from horizontality to verticality. The skyscraper will look

as if it will be the final, definitive typology. It has swallowed everything else. It can exist

anywhere: in a rice field, or downtown – it makes no difference anymore.”3

Koolhaas further enquires a hypothesis which never was considered, that cumulatively the

endless contradictions a generic city would go through might actually prove the richness of it

giving an identity to each case.4 The approach is generic, agreed; but with different social,

cultural, economic and ecological scenarios can the ‘generic’ become ‘individualistic’? This

further leads to an intense confusion, questioning the applied approach in these models of

urban development. Giving a reference of Brasilia, James Holston explains that formal

equivalence and functional differentiation reveals a number of contradictions in the intention

of modern planning; where the functions remained spatially separate and the organisational

principles or the form appeared similar.5 These very approaches failed in certain other

scenarios like Detroit where the entire city failed to operate after a while because of its very

operatable and promising element of growth, the built, the rapidly over grown factory setups.

The traditional urban design methods proved less efficient, costly, slow and inflexible in the

growth of new infrastructures within, adapting with the local ecology, for urban de-

densification. Instead landscape felt as a more promising domain to address to these

issues.6

Conflict between methodology and conditions

Belgian urban designer, Marcel Smets attempts to promote landscape as a saviour to

contemporary urban development. Smets has categorised spatial design concepts

explaining how contemporary designers work with a condition of “uncertainity”7 and imply it

as indeterminacy for future development; using its incapability of shaping a definite form as a

potential tool for evolution of the urban.

At this juncture we have two contradicting ideas: one if generic, with the locale (ecology,

society, culture and economy) can be used as a rescuer from the generic itself; the other

perceiving the urban through a lens of landscape, creating a situation which can imbibe

future fluxes. In both these conditions one cannot stop the expansion of the physical

boundaries of the urban, the sprawl. Sprawl embraces theatricality, hybridity and even

density in abundance; sprawl is simply the contemporary urban condition.8

America’s urbanisation through the entire twentieth century explains the case where urban

as a form rapidly grew. As Charles Waldheim states in his writing “Motor City” that flexibility,

mobility and speed made an international model for industrial urbanisation; traditional

models of dense urban arrangements were quite literally abandoned in the favour of

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

5

escalating profits, accelerating accumulation and the culture of consumption.9 Detroit as a

model of industrial urbanisation fitted perfectly as an example for this. Figure 2 illustrates the

rise and hollowing of the urban form of Detroit in the twentieth century. In the second half of

the twentieth century, the city of Detroit, once the fourth largest city in the US, lost over half

of its population. The process of decentralisation started in 1920s when Henry Ford

announced the relocation of his production line outside Detroit to reduce production costs.

Detroit, once famous for its blue collared jobs in the entire US, and perhaps the entire world,

had risen from a nowhere into remarkable industrial town. It was in its peak of being a

resourceful, profit making industrial hub. In the next 80 years, because of it growth pattern of

the past 80 years, no one even remotely anticipated the collapse of this industrial town. It

had turned into an empty sprawl. The horrifying collapse, of once the industrial hub of the US

becomes a ground of reference while devising urbanity on the other side of the world, in the

far east of China; where in the urge to grow faster planners tend to repeat a similar mistake

without reading the future scenarios.

The mistake then could be not only in terms of planning methodologies, but in the economic

policies, environmental and ecological measures and the sensitivity shown towards the local

existing society and their cultural behaviour.

Figure 2: Ground Diagrams, Downtown Detroit by Richard Plunz, (Source: “Detroit is everywhere”, Architecture Magazine, 85(4))

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

6

Economic policies: Urban growth

What is seen in China, post 1980s, is a similar condition but only with a much bigger scale.

And, to cater to this lucrative urbanity, the methodologies of planning are encouraging

sprawl. The existing cities are expanding at an uncontrolled rate, whilst there are new being

added to the count. With one of the policies of the Chinese Government where the local

authorities can define the percentage of taxes; the authorities are becoming self-competitive.

This competition within and among territories is becoming a factor for the raging urbanity,

eventually leading to intensifying of conditions. This is leading to a situation which is creating

hollowness in the city and is leading to sprawl of the urban, which once has already proved

as an urban disaster. This puts the policies of urban growth of China into question.

For instance cities like Guangzhou, Hangzhou which were considered as Tier II cities; are

now being transformed rapidly, and expanding at an unimaginable rate. Economic potentials

have been identified in these regions both in terms of manufacturing and in terms of logistics

of the manufactured goods because of the proximity of these cities to the international trade

routes via sea. Ever since the neo liberal policies were accepted by the Chinese authorities

in the 1980s the growth started reflecting within a decade, from the early 1990s.

Hangzhou, a small industrial city in the Yangtze River delta, then with the presence of varied

light industries, textile industries and agriculture was recognised as a base for logistics hub

for coastal China. Investors identified the economic potential of this territory and considered

establishing market for this region. Investment for global investors in building infrastructure

and human resource was dirt-cheap. In the last decade of the twentieth century various

industries, ranging from electronic, bio-medical, mechanical, food and agro-industries were

established. A diversified market reflected in the GDP of the province; from 1992 to 2000, in

a span of eight years it raised three folds. This highlighted on the high yielding side of this

province, and hence, the State council in the year 2000 declared the establishment of the

transitory systems, an international airport and a sea port within the province; providing a

further compatibility for growth within, competing against its viable potential neighbouring

provinces.

Similarly, Guangzhou, another city which started growing in the last decade of the twentieth

century has made a remarkable progress. This province, once known for its local products

and artisans famous for wood and ivory carving, jade sculptures, Cantonese embroidery and

for the presence of many historic structures; now has dedicatedly turned into another

industrial hub. Apart from software industry, this culturally strong town now has automobile

assembly lines, heavy industries and biotechnology industries. Since the province is located

in Pearl River delta, this province too becomes a hub for logistics.

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

7

Chengdu, a landlocked region with water logistic network unavailable, determined potential

in the software and computer industry attracting giants like Intel, IBM, Motorola, Wipro,

Microsoft, HP, Siemens and many more; thereby negating the requirement for physical

connectivity.

Progress is inevitable.

All these provinces show an uncontrolled pattern of growth only because of the economic

policies and the competition created within. This surely is providing an economic boom, but

its unpredictability is becoming a major threat from an urban evolution point of view.

Inference

In the past, industrial giants have manipulated and fiddled with economic policies and

government authorities to yield high profits. Detroit as an urban model has seen an

unexpected collapse within a short span as the automobile industry suddenly was relocated.

However, the scale of industry in Detroit then, or for that matter in any industrial towns, both

in America as well as Europe did not seem enormous in comparison to the presently

booming Chinese territories. These Chinese urban models, unlike the past models of

America and Europe are not just confined to automobile industry, but are a conglomeration

of several industries and this makes conditions scarier. The rapidity in growth, as compared

to the previous models is enormous and the methodology implicated is still analogous to the

aforementioned models. If Detroit as a model failed and is still recovering from its urban

failure; the question raised is what would the consequences be if the upcoming Chinese

urban models fail? This hence, is becoming a matter of concern among the urbanists and

analysts about the unexpected and unprecedented chaos which might likely be created.

In the book “The Three Ecologies”, Felix Guattari expresses that the domestic life is being

affected by the gangrene of mass-media consumption. By the standardization of the mass

behaviour, society and culture are being ‘ossified’, and the relation between people and

communities is being reduced to the meanest of the expression!10 The relation between

subjectivity and exteriority in both the domains of social and ecological are compromised in a

way. He further states, “…it is the ways of living on this planet that are in question, in the

context of the acceleration of techno-scientific mutations and of considerable demographic

growth.”11 The growth is tremendous and along with the political stance another major factor

influencing the growth of the present urban setup is the rise and reach infrastructure is

providing the developers to penetrate into the urban and reach the masses.

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

8

Physical Infrastructures: Beyond mere Functionality

One of the primary elements needed for urbanisation is the provision of physical

infrastructures like roads, highways, water supply, sewers and drains, canals, public

amenities etc., and the other fragments of urban like the residential, commercial, recreational

and economic centres spring around it. As Kennith Frampton states: “…essentially 19th-

century city fabrics in the early 1960s have since become progressively overlaid by the two

symbiotic instruments of Megalopolitan development - the freestanding high-rise and the

serpentine freeway”.12 The quality of lifestyle and the evolutionary scope for it depends on

the quality and structure in which these elements of urban are laid, and the quality and

structure of the elements of urban are directly proportional to the efficiency of the system of

physical infrastructure devised. For infrastructure, it is also important how it functions beyond

its mere functionality. It reasons how infrastructure becomes capable of performing more

than just what it can, binding together various parameters considered in any urban

intervention; like the primary domains of ecology, economy and sociology synchronising and

operating in co-ordination.

Figure 3: The map based indicates Haussmannian street network in Paris between 1850 and 1870 (Copyright 2004, Mark Jaroski)

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

9

The initial conscious attempts to use infrastructure to bind the socio-cultural fabric in the

urban setup with the ecological setup began as early as in the mid nineteenth century.

During this period Paris went through a major alteration. As Emily Kirkman states, Paris

became a hub for industrial change and cultural advancement, it became a home for many

immigrants, overcrowding the ancient district. Paris soon started tumbling to an unexpected

growth and soon became an unhygienic epidemic city.

The tight confines of Medieval Paris were hindering city’s potential and desire to transform

into a more organised urban centre. In order to bring some rationality and to transform and

liberate Paris from the menace Napolean III commissioned an urban renovation project to

Baron Haussmann. The Parisian boulevards, parkways, highways and road network were

being redesigned and many were being added to the existing. The drains and sewers too

faced a severe problem and the direct impact of it was seen on the societal behavioural

changes. Baron Haussmann was among the first visionaries to formulate a metropolitan-

scale response to this function and to recognize the opportunity it provided to "modernise"

Paris.13 The boulevard combined many functions within and operated beyond the mere

function of being a boulevard. The rebuilding of Paris between 1850 and 1870 is a crucial

moment in urban history. The attempt by Haussmann to rationalise the urban space is one of

the formative legacies of urban planning. His approach, although initially was criticised by his

contemporaries were re-evaluated when modernist methodologies of urban planning were

reasoned and questioned. Its wide boulevards have given Paris its present identity, the

boulevards with shops and cafés and commercial facades determine a new urban typology.

It changes the everyday lives of the Parisians and helped evolve and reshape the societal

behaviour and the local culture.

As a part of urban renovation, Parisian boulevards became an organisation of integrated

sewers, water, parks, roads, pedestrian; this was a pragmatic example of conglomerating

multiple layers. Edmund Bacon states with respect to Haussmann’s Paris, “reversal in the

direction of energy, from the outward explosion of avenues and palaces of the Louis Kings to

the implosion of the connecting and life-giving boulevards of Haussmann14”.

During the same period Haussmann’s, American contemporary Fredrick Law Olmsted was

designing Boston’s Emerald Necklace. For Olmstead proposed housing, commercial and

recreational venues within the domain of Landscape provided along with circulation of space

to respire within the nineteenth century urban. These were to be realised in conjunction with

the existing and proposed infrastructural networks and had to function in coordination with

the existing natural ecological systems. As Jacqueline Tatom states that projects like these

were remarkable during that era because they suggested modern urbanism that conceived

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

10

an efficient circulation not as an independent system but it considered merging other social

and cultural setups of the everyday urban life, as well as integrating services like drains,

sewers and water supply.

Also, another notable project is Manhattan’s Central Park designed by Olmsted along with a

British architect Calbert Vaux. Central Park was a unique landscape for its period since it

was a radical approach towards landscape as it conceived beyond the simple realm of

landscape. The landscape intervened with the urban domain understanding the social

dynamics and provided scope for the adaptation with the upcoming future culture. The

landscape here operates even through a frame of environmental engineering; it forms fresh

water reservoirs and collects the surface run-off, in Croton reservoir majorly. As Jorge Otero-

Pailos suggests, for its period the Central Park was to be a republican institution, where all

the classes of society shared a single platform to mingle within themselves collectively

raising the spirit of democracy. It meant to be, and in a way it still is an escape from the

urban congestion. The ideas behind Central Park were accented by the moralistic overtones

of the American transcendentalists who believed in a metaphysical need for individual

communion with nature, as a way of salvaging personal autonomy from for individual

communion with nature, as a way of salvaging personal autonomy from

Figure 4: Central Park in the Manhattan borough of New York City The park acts as a relief from the dense urban condition, from the skyscrapers surrounding it

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

11

the social conformity spawned by the nascent commercialism of American culture15. The

appreciable stride of Vaux and Olmsted is their attempt relating the non-urban with the

urban; in the favour of processes they ruled out over a, so called ‘utopian’ approach. As

Koolhaas states the park is a formal indeterminacy, an example of liberation from the formal

coerciveness of architecture, ‘a kind of erasure from the oppression, in which architecture

plays an important role’16. Here the role of architecture was subdued by landscape. Apart

from the visual influence the landscape here acted as a relief from the architecture itself, and

helped derive an identity and evolve a local culture for Manhattan.

Realisation

The previous examples provide an in-depth analysis of the performance of landscape and

infrastructure functioning in co-ordination in an urban domain, and its influence in shaping

the culture, ecology and economy within context and its influences both around as well as in

time. These examples, however, are performing beyond what they are meant to be, although

initial research in conceiving the ideas was not so intense. It is only when these projects

were further revaluated, after its undergone mutations; they have disclosed the critical

changes which have undergone to evolve the project to its current state.

Certainly, the depth of understanding in the early post-industrial approach of urban design

was confined and did not consider multiple parameters and factors that influenced an urban

evolution; it rather perceived urban through a purview of constructing it, rather than a

conscious approach towards a processual strategy. The modernist perception of urban

design from the frame of ‘Architecture’ restricted, to a great extent the evolution of urban and

solidified the city without providing scope to operate beyond its functional expectations. What

many urban designers did not visualise back then is that an urban cannot be ‘designed’ by

being narcissistic; giving urban a form, a definition to realise its identity. Rather, an urban

needs to, and irrespective of its design approach, will evolve in time simply because it is not

a single persons vision but an urban is a cumulative effect. It is influenced by various

parameters, right from society or community and culture (and variations within), regional

conditions (or ecology), economic and political conditions, and performs beyond a sole

vision.

The New Methodologies

As Bernard Tschumi states, “Urban Design historically has oscillated between the

treacherous poles of social control and manipulation, on one hand, and banal orchestration

and management of urban services, on the other17”; the approach needed had to be more

profound and radical. His project, Parc de la Villette in Paris is a conscious example of

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

12

including multiple layers which would start conflicting within to evolve in time. The park

designed, unlike conventional parks, intended of creating a space that existed in vacuum,

without any historical precedent.18 The park goes against the conventional signage and

representations that have infiltrated architectural design and allowed for an existence of

“non-place”. “Non-place”, envisioned by Tschumi, is an appropriate example of space and

provides a truly honest relationship between the subject and the object.19 Visitors react to the

entire organisation of landscape and sculptural pieces without the scope to cross refer to

previous works of historical parks or architecture. By allowing visitors to experience and

assimilate the deconstructed architecture of the park within the constructed vacuum; the time

recognitions and activities that start taking place in that space begin to acquire a more vivid

and authentic nature.20

Unlike the present parks in that period, Parc de la Villette is not a reflection of a traditional

approach of design. The park functions as a platform for evolving culture and maturing

interaction. The frame of the park, due to its roots in deconstructivism, has the ability to

change and react to the functions that it holds within.21 The relations between the park and

cultural interactions are dynamic and have the ability to undergo change. The

deconstructiveness of the park is seen in its ability to host these interactions in an

environment that is constructed for a cyclic change and reaction. This approach tends to

bring radicality in the conception strategy as compared to the conventional park design

strategies; it filters landscape’s functional role to its pragmatic level and triggers an open

dimension for the perception of space, thus making the response unpredictable.

Critical arguments, Conscious implications

Post Tschumi’s “Park de la Villette” a rigorous enquiry was generated among urbanists to

question the traditional methods of urbanism. Landscape was being, for the first time, rather

than architecture, considered a potential element to set an urban which has the capability to

adapt to the present conditions and evolve and curate the culture of the territory. Park de la

Villette became an experiment to test a new model of urbanism. This led to an evolving of a

theory “Landscape Urbanism”. Landscape Urbanism is a theory arguing landscape, rather

than architecture, is more capable of organising the city and enhancing the urban

experience.

Speaking at the Oslo School of Architecture, Douglas Spencer states, “Both, landscape and

infrastructure are territorial practices. Each functions as a kind of ‘groundwork‘, shaping,

organising and servicing bases upon which forms of social, economic and ecological

relations operate22”. This is reflected in OMA’s project in 2000, Park Downsview, Toronto.

Koolhaas’s conception of “Tree City”, for the project Downsview, is an attempt of using trees

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

13

rather than buildings to serve as a catalyst for urbanisation. He argues that vegetal clusters

rather than built forms would provide site identity, and conceives the entire project as an

urban domain constituted of landscape elements. OMA strategizes the entire project as a

processual development, and that the phases of its development will evolve the site in time.

“Tree City”, therefore is a plan for attainable growth rather than a proposal to create an

extensive bulk.

Located at the juncture of major transit lines, “Tree City” intends to operate as a point of

destination and dispersal. Currently in the sub-urban region, it anticipates of being in a

condition of “city” or a dense urban setup in the future, for which landscape tends to provide

scope to adapt to the fore coming conditions. James Corner, in his essay “Terra Fluxus”

refers to one of the qualities of Landscape Urbanism as process in time, where he describes

urbanisation as a dynamic process characterised by terms like fluidity, spontaneity and non-

linearity as opposed to stability, predictability and rationality. This opens to a conscious

intention of considering certain meta-parameters which pushes to reason beyond its mere

response. The analysis and response to the perception of future urban scenario hence

seems to be much more sophisticated.

Conclusion

Horizontality and Sprawl, like in most American cities, is becoming a condition in the

Chinese setup; or for that matter in any upcoming urban, and hence is a new urban reality.

Figure 5: “Tree City”, Plan of Park Downsview, Toronto Designed by OMA, Rem Koolhaas (Source: CASE: Downsview Park Toronto)

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

14

As many theories of urbanism tend to ignore this fact, or more recently attempt to retrofit it in

theories like New Urbanism, Landscape Urbanism accepts it and tries to understand the

conditions thoroughly. Traditional urbanism approaches, although consider this aspect, have

a small and limiting scope. Landscape Urbanism uses ‘territories’ and ‘potential’ instead of

‘programme’ to define a place’s use; it finds thinking in terms of adaptable ‘systems’ instead

of rigid ‘structures’ as a better way to organise space.

Since in the recent years, urban is evolving not only because of the schema for infrastructure

development but also because of the political conditions, acceptance of neoliberal and trade

policies, alterations in social and cultural behaviour, and the changes in ecological, regional

and environmental conditions, the growth in the coming future seems huge and erratic. Asia

(and more specifically China) is a major ground of experimentation, where the conditions are

exactly the same which America in the past had. It is left to the future urban visionaries to

deal with these scenarios.

Exploring the possibility of Landscape Urbanism as a critically informed practice, the

urbanists need to derive a design methodology which contradicts the negative factors of the

prior approaches and perceives the future of urban through a lens of Landscape. Looking at

the scenario of rapid transformations, we need go to the basic level, investigate the

pragmatic structure to device a Metamorphic Urbanity which has the capability to adapt,

accept and experience both physical and metaphysical transitions.

Landscape Urbanism, as a theory, not only seems promising in post-industrial cities or in

conditions of rapid urbanisation of Asia, but seems promising in any hypothetical or existing

scenario and scale, anywhere because of its adaptability and credibility towards the subtle

nuances of the urban or global conditions.

ASCA 101 NEW CONSTELLATIONS NEW ECOLOGIES

15

References 1 –Harvey, David (2005), A Brief History of Neoliberalism, p.121, (Neoliberalism ‘with Chinese Characteristics’), New York, Oxford University Press Inc. 2 –Guattari, Felix (translated by Pindar, Ian) (2000), The Three Ecologies, p. 27, London, The Athlone Press 3 –Koolhaas, Rem, Mau, Bruce (1995), S,M,L,XL, p.1253 (Essay: The Generic City, Guide 1994); New York, The Monacelli Press 4 –In the essay “The Generic City”, Rem Koolhaas puts forward a hypothesis which becomes a radical question of enquiry; can the existing approach in building our approach become an evolutionary methodology? 5 –Holston, James (1989), The Modernist City, An Anthropological Critique of Brasilia, p.153, Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press 6 –Kelly Shannon argues Landscape’s role in the modern urban development approaches as against traditional urban design theories perform better; defending to the discourse of “Landscape Urbanism” as an innovative design practice. 7 - Waldheim, Charles (2006), The Landscape Urbanism Reader, p.146, New York, Princeton Architectural Press (Essay: From Theory to Resistance: Landscape Urbanism in Europe; Shannon, Kelly) 8 –Bekaert, Geert (2002), After-Sprawl, p.11, Rotterdam, NAi Publishers 9 –Charles Waldheim states in his writing “Motor City” referring to Detroit as an international model of industrial urbanism; shaping the City: History, Theory and Urban Design (2004), p.80, 81, New York, Routledge 10 –Guattari, Felix, translated by Pindar, Ian (2000), The Three Ecologies, p.27; London, The Athlone Press 11 –Guattari, Felix, translated by Pindar, Ian (2000), The Three Ecologies, p.28; London, The Athlone Press 12 –Frampton, Kennith (Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance) (1983), p.17, The Anti-Aesthetic, Editor: Foster, Hal, Port Townsend, The Bay Press 13 –Jordan, David (1995), Transforming Paris: The Life and Labors of Baron Haussmann, New York, The Free Press 14 –Gandy, Matthew (1999), p. 23, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 24, No. 1, London, Blackwell Publishing 15 –Otero-Pailos, Jorge (DEBATES: ‘Bigness’ in context: some regressive tendencies in Rem Koolhaas’ urban theory) (2000), p. 381, City, Vol. 4, No. 3, Carfax Publishing 16 –Koolhaas, Rem (1996), p. 63, Conversation With Students, New York, Princetom Architectural Press 17 –Tschumi, Bernard (2004), p. 500, Event-Cities 3 – concept vs. context, Cambridge (Massachusetts), London , The MIT Press 18 –Tschumi, Bernard (1987), p. 32, Cinégramme folie: le Parc de la Villette, Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton Architectural Press 19 –Papadakēs Deconstruction in Architecture (1988), p. 20-24, Academy Editions 20 –Tschumi, Bernard (1987), p. 108-119, Disjunctions, Cambridge (Massachusetts), The MIT Press (on behalf of Perspecta) 21 –Tschumi, Bernard, (Edited and Photographed: Futagawa, Yoko) (1997), p. 32, Bernard Tschumi “Parc de la Villette”, GA Document, 10, Tokyo, ADA Edita 22 –Spencer, Douglas (2010), Groundworks: Lecture at AHO’s Institute of Urbanism and Landscape (In a symposium ‘Landscape and Infrastructure), Oslo [source: terraincritical.wordpress.com]