Lying Cow – By Vincent Van Gogh - Final Draft

-

Upload

jake-thomas -

Category

Documents

-

view

95 -

download

1

Transcript of Lying Cow – By Vincent Van Gogh - Final Draft

Christopher ThomasWRTG 3020Prof. QuinlanMay 5, 2007

The Bovine State-of-Mind

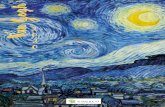

Vincent Van Gogh’s Lying Cow portrays an unimposing bovine resting silently on a

patch of grass that urges us to concentrate our awareness on the present moment, so that we may

recognize the beauty that pervades all things. Present-centered awareness is the message. As

expressed through Buddhist beliefs: By constantly being mindful of self, life, and death—until it

becomes second nature—we learn how to advance further along the path to peace and

enlightenment1.

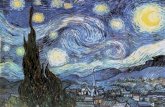

My analysis of Vincent Van Gogh’s, Lying Cow begins with a description of the piece

from a purely physical standpoint. In other words, I will begin by addressing only what is

directly on the canvas, and the conclusions or ideas that these physical components illicit. Van

Gogh’s work was most closely associated with Post-Impressionism, but this movement was

loosely defined, and spawned tremendous variation. In general, the Post-Impressionist paintings

were characterized by thick application of paint, vivid colors, large distinctive brushstrokes, and

a distortion of form in an attempt to give the viewer a feeling or “impression” of the work2.

These characteristics can also be defined as impasto, which results in a very lumpy, uneven

collection of paint on the canvas3.

I believe the qualities behind Post-Impressionist art allowed the viewer greater freedom

to interpret a given piece in his or her unique frame of reference. For example, the cow is

painted with broad strokes, and loosely blended colors, resulting in minimally defined

boundaries between subject and background. This lack of boundary in the painting gives the

viewer the impression that the cow is closely connected to its environment.

The portrayal of form, which evolved heavily during this time period, is often defined as

the total structure or synthesis of all visible aspects and the manner in which they interact4. The 1 Maguire, Jack. Essential Buddhism: A Complete Guide to Beliefs and Practices. Roundtable Press Inc. New York 2001.2 Rewald, John. Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gaugin, revised edition. Secker & Warburg Press. London 1978.3Delahunt, Michael R. Artlex Art Dictionary. August 1996. <http://www.artlex.com>4Delahunt, Michael R. Artlex Art Dictionary. August 1996. <http://www.artlex.com>

form of this painting appears dreamy and vague, and results primarily from a lack of detail in

both the subject and its surroundings. Accompanying this, is the lack of apparent dimension in

this painting that allows the viewer to feel the cow in closer contact to its environment, rather

than simply situated at some specific point in time. Moreover, the background is a loose

blending of green with occasional brown, implying that the cow’s current situation or the

specifics of its location are irrelevant. The aforementioned qualities of this piece harmonize to

give the viewer the impression of an animal in very close relation to its surroundings; this does

not result out of a wealth of detail, but rather a melding of subject and background.

Of great importance is Van Gogh’s choice to paint the subject as occupying the vast

majority of the frame. This is an element of the artwork’s overall composition, which is the plan,

placement, or arrangement of the elements in a work. These various elements can be ascribed

relative weights. The weight is the visual dominance, emphasis, or force of attraction of that

portion of the composition. The weight of a given component is dependent upon the subject’s

placement in relation to other parts, as well as its psychological pull on the viewer5. In Lying

Cow, Van Gogh places diminished significance on the cow’s surroundings by only attributing a

small area of the canvas to them. This serves to emphasize the presence of the subject itself,

leaving the viewer to feel as though the cow is of some great nature, and perhaps deserves further

attention.

Upon deeper probing, I was astounded to realize the cow was looking directly at me.

With eyes fixated upon the viewer, the cow implies that an exchange between man and animal

may be necessary, that perhaps the viewer could learn something or great value from the

unimposing cow. Van Gogh paints the stoic creature with legs that are distorted so as to appear

shorter than normal. This additional distortion of form gives the cow a more lovable or cuddly

feeling to the viewer, which in turn urges us to do just that: love the cow, and give it further

attention.

Upon seeing Van Gogh’s Lying Cow for the first time I immediately relaxed into what

Arthur Deikman refers to as, Receptive Consciousness. Defined as when awareness is dominated

by Now rather than Time, receptive consciousness involves an intention to receive one’s

surroundings in their entirety without analysis or imposition6. What results is a de-emphasis of

5 Delahunt, Michael R. Artlex Art Dictionary. August 1996. <http://www.artlex.com>6 Deikman, A.J. A functional Approach to Mysticism. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7, No. 11-12, 2000, pp.75-91.

the self, and a greater capacity for world-centric awareness. In my own words: when I saw this

painting my mind was silenced. It relaxed for a brief period of time, and ceased to question the

value of the piece of art, and began, simply, to experience it. I was, for a brief period, able to

exist completely in the present moment.

In support of my experience, I draw on the writings of, the philosopher, Ken Wilber, who

says that meaningful art has the power to silence us. That, upon seeing something, that for

whatever reason is beautiful to us, we stop trying, and imposing, and controlling, and we simply

exist with the artwork. In his essay entitled: Integral Art and Literary Theory: Part 2, Wilber

says: Great art has this power, this power to grab your attention and suspend it: we stare,

sometimes awestruck, sometimes silent, but we cease the restless movement that otherwise

characterizes our every waking moment7. When I first laid eyes on this piece, I was calm, and

this was my spiritual experience. Wilber calls this state-of-mind contemplative awareness,

[when] our own egoic grasping in time comes momentarily to rest. Deikman refers to the state-

of-mind evoked while viewing great art as receptive consciousness. But, in this case, I call it the

Bovine State-of-Mind, as it is radiated from the cow’s presence in this painting.

Van Gogh’s Lying Cow is not munching grass or dutifully nursing a calf, it is simply

sitting and staring specifically at a viewer who could learn something from it. The cow is not

imposing, or altering, or pretending to be something it is not, but rather exists completely in the

present, and for the present. The cow is in a perfect state of contemplative awareness or

receptive consciousness, or any of the other multitudes of terms for this experience.

The spiritual truth that this cow is transmitting to the viewer is beautifully described by

Ralph Waldo Emerson, who states: These roses under my window make no reference to former

roses or to better ones; they are for what they are; they exist with God today. There is no time

for them… But man postpones or remembers; he does not live in the present, but with reverted

eye laments the past, or heedless of the riches that surround him, stands on tiptoe to foresee the

future. He cannot be happy and strong until he too lives with nature in the present, above

time”8. In this example, the cow is like the roses beneath Emerson’s window: through their

silent presence we are, again, reminded of the impermanence of time, the extraneousness of

comparison, and the sheer beauty that simply exists in our universe. In this new light, Lying Cow

7 Wilber, Ken. The Eye of Spirit. Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boston, MA. 2000. pp. 87-126.8 Emerson, R.W. Selected Prose and Poetry. San Francisco: Rinehart Press. 1969.

takes on deeper meaning, as it becomes a symbol for the capacity of great art to free us to exist in

the present moment as we experience an image that we perceive as exquisite.

The beauty that radiates from Lying Cow does not end at the boundaries of its physical

form. Rather, its existence is proof of the magnificence that emanates from all things in the

universe. In other words, if we are capable of seeing so much wisdom and beauty in this ordinary

Lying Cow, what would happen if we could take this a step further to recognize this same beauty

in every creature, in every experience, in every moment of every day? Wilber poses an answer:

You are released from grasping, released from time, released from avoidance, released

altogether into the eye of Spirit, where you contemplate the unending beauty of the Art that is the

entire World9. Lying Cow and all beautiful art exists for just that purpose, to bring us closer, if

only for an instant, to the infinite beauty of the universe.

9 Wilber, Ken. The Eye of Spirit. Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boston, MA. 2000. pp. 87-126.