Living Music - London Symphony Orchestra · 2017. 8. 25. · He continued his studies with Klaus...

Transcript of Living Music - London Symphony Orchestra · 2017. 8. 25. · He continued his studies with Klaus...

-

London Symphony OrchestraLiving Music

London’s Symphony Orchestra

Sunday 25 January 2015 7.30pm Barbican Hall

MAHLER’S FOURTH SYMPHONY

Toshio Hosokawa Blossoming II Ravel Piano Concerto in G major INTERVAL Mahler Symphony No 4

Robin Ticciati conductor Simon Trpčeski piano Karen Cargill mezzo-soprano

Concert finishes approx 9.50pm

Broadcast live on BBC Radio 3

-

Living Music In Brief

2015/16 SEASON LAUNCH

We’re delighted to announce details of a brand new season of LSO concerts, taking place between September 2015 and June 2016. The concerts are now available to browse on lso.co.uk; online booking will open on 4 February, with telephone booking available from 18 February. LSO Friends get priority booking, along with a range of other benefits; find out more at lso.co.uk/lsofriends.

lso.co.uk/201516season

CONTESSA YOKO CESCHINA (1932–2015)

The LSO was greatly saddened to learn of the death over the weekend of 10/11 January of Contessa Yoko Ceschina, a loyal supporter of the Orchestra. A trained classical harpist, Yoko supported a large number of classical music organisations and held close relationships with some of the world’s leading artists, most notably Valery Gergiev. Yoko was a wonderful friend of the LSO, offering generous support to the organisation and players. She will be greatly missed, and our deepest sympathies are with her friends and family.

A WARM WELCOME TO TONIGHT’S GROUPS

The LSO offers great benefits for groups of 10+ including a 20% discount on tickets. Tonight we are delighted to welcome: Mrs E Budd & Friends and Merchant Taylors’ School

lso.co.uk/groups

2 Welcome 25 January 2015

Welcome Kathryn McDowell

Welcome to this evening’s LSO concert at the Barbican. Following performances in Vienna and Linz, Robin Ticciati and the Orchestra bring the programme back to London, beginning with a work by Japanese composer Toshio Hosokawa, followed by Ravel’s jazz-inspired Piano Concerto and Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. Robin Ticciati has been a regular guest on the podium since his LSO debut in 2010, and this performance and tour mark a welcome return.

The Orchestra is also joined on stage this evening by two soloists: pianist Simon Trpčeski and mezzo-soprano Karen Cargill. Both artists are long-standing friends of the LSO and last appeared in the 2013/14 season, with Karen Cargill performing with us again in June this year in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with conductor Bernard Haitink.

I hope you enjoy tonight’s concert, which is also being broadcast live by our media partner BBC Radio 3, whom I would like to thank for their continued support. Following the concert, you will be able to listen back to the performance on BBC iPlayer.

Next Sunday, 1 February, David Afkham, a previous Assistant Conductor of the LSO and winner of the 2008 Donatella Flick Conducting Competition, will conduct the Orchestra in a programme that includes works by Beethoven, Brahms and Webern. Do join us then.

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL Managing Director

-

London Symphony OrchestraLondon’s Music

lso.co.uk/findmeaconcert

Something for every mood with the London Symphony Orchestra

To roll our online dice, visit: lso.co.uk/findmeaconcert

-

PROGRAMME NOTE WRITER

TOSHIO HOSOKAWA

4 Programme Notes 25 January 2015

Toshio Hosokawa (b 1955) Blossoming II (2011)

I have also given this Blossoming another meaning. In a lecture on the theme of ‘The Westernisation of Present-Day Japan’ by the first master of modern Japanese literature, Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916), Sōseki severely criticises the fact that Japan in his day, on suddenly encountering western civilisation, accepted it as it was (a superficial blossoming) rather than letting it slowly mature in its own internal world. Even today, over a hundred years since Sōseki’s time, we Japanese, rather than reflecting on our own roots and creating our own culture from them, maintain an interest only in culture coming from outside. We have become obsessed by pursuing western civilisation as if, were we not to adopt it, we would fall behind the times: we have forgotten our own point of departure. In creating my own music, I want to base it firmly in my own musical and cultural roots, and from there let it blossom internally.

Blossoming II was commissioned by the Edinburgh

International Festival and is dedicated to its first

performers, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and

Robin Ticciati.

I have composed many works on the theme of ‘blossoming’; expressing musically the energy of a flower’s blossoming is deeply significant for me. I perceive music as having plant-like development and growth, and I want to continue composing with a different viewpoint from that of European composers, who tend to construct their music architecturally. Although Blossoming II is a chamber orchestra version of Blossoming for string quartet, it is not an exact arrangement of the original work and many parts have been rewritten.

A distinctive feature of the Blossoming pieces is that at the beginning there is one long, sustained note in the middle register, out of which develops the mother’s body; from which is born a song (a fragment of melody) – the flower. This sustained note symbolises the surface of a pond; sounds that are lower than the note represent what is under the water, while those that are higher portray the world above. The flower grows from the womb of harmony, lying dormant deep beneath the surface, and continues to rise towards it. The inspiration for this series came from a book on Buddhism about the way in which the lotus blossom comes into flower.

‘Music is the place where notes and silence meet.’

Toshio Hosokawa

SEASON 2014/15:

CONTEMPORARY VOICES

Thu 23 Apr 7.30pm, Barbican

Pierre Boulez:

90th Birthday Festival

Peter Eötvös conductor

with Aftershock

Post-Concert Club Night featuring

LSO musicians and

LSO Soundhub composers

Fri 5 Jun 10am–1pm & 2–6pm,

LSO St Luke’s

LSO Discovery:

Panufnik Composers Workshop

François-Xavier Roth conductor

Sun 5 Jul 7.30pm, Barbican

Jonathan Dove:

The Monster in the Maze

Sir Simon Rattle conductor

lso.co.uk/contemporary-voices

-

A number of Hosokawa’s large-scale works have been premiered in the last few years, including the opera Matsukaze, staged by Sasha Waltz in 2011 at La Monnaie in Brussels; Singing Garden, inspired by Vivaldi‘s concertos for recorder; his monodrama The Raven for mezzo-soprano and ensemble, premiered in Brussels in 2012; Meditation, dedicated to the victims of the Tsunami disaster in Fukushima, premiered in 2012; Klage for soprano and orchestra, based on a text by Georg Trakl, first performed at the 2013 Salzburg Festival; and the trumpet concerto Im Nebel, premiered in 2013.

The 2014/15 season started with the world premieres of two pieces for orchestra: Aeolus for harp and orchestra (Naoko Yoshino and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra), followed by Fluss for string quartet and orchestra (Arditti Quartet and WDR Symphony Orchestra). Following its world premiere in Cologne, Fluss was performed at the Concertgebouw Bruges, which dedicated a three-day festival to the works of Hosokawa.

Toshio Hosokawa has received numerous awards and prizes. He has been a member of the Academy of Fine Arts Berlin since 2001 and a fellow of the Institute for Advanced Study in Berlin since 2006. He is the Artistic Director of the Takefu International Music Festival and a frequent guest at prominent contemporary music festivals, such as the Pacific Music Festival in Sapporo, Japan, Salzburg Biennale, Rheingau Musik Festival and the MITO SettembreMusica Festival in Milan and Turin. In spring 2012 he was Composer-in-Residence at the Tongyeong International Music Festival. In summer 2012, he began a three-year appointment as Artistic Director of the Suntory Hall International Program for Music Composition.

Toshio Hosokawa, Japan’s pre-eminent living composer, constantly explores the boundaries between cultures. His distinctive compositions examine the relationship between western avant-garde art and traditional Japanese culture, and are influenced by the static structures of the Gagaku music of the Japanese court. Nature and its inherent transience also greatly influence his compositions. ‘Transience is beautiful’, says Hosokawa, who uses the Buddhist notion of balance between life and death to describe his musical language: ‘The tone comes from silence, it lives, it returns to silence’.

Born in Hiroshima in 1955, Toshio Hosokawa moved to Berlin in 1976 to study composition with Isang Yun. He continued his studies with Klaus Huber and Brian Ferneyhough. Initially Hosokawa based his music on the western avant garde, but he soon began to explore new musical terrain, composing his first opera Vision of Lear in a style that brought together eastern and western influences to great critical acclaim. His second opera Hanjo (2004) is regularly programmed by opera houses and festivals.

Hosokawa made a name for himself at new music festivals in the early 1990s with chamber music works such as Landscapes I–V. Following the success of his oratorio Voiceless Voice and his orchestral work Circulating Ocean, which was premiered by the Vienna Philharmonic at the Salzburg Festival in 2005, his music began to be performed in concert halls around the world. Chamber music is still a big part of Hosokawa’s compositional output; in 2008 he wrote Stunden-Blumen, a quartet with the same instrumentation as Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. Japanese instruments are utilised in many of his works, often combined with traditional European instruments.

lso.co.uk Composer Profile 5

Toshio Hosokawa Composer Profile

-

PROGRAMME NOTE WRITER

ANDREW CLEMENTS is Chief

Music Critic for The Guardian.

His study of the British composer

Mark-Anthony Turnage is published

by Faber & Faber.

6 Programme Notes 25 January 2015

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) Piano Concerto in G major (1929–31)

1

2

3

Classical forms. The opening Allegramente is built upon a pair of themes, the first announced by a solo piccolo after an initial whip-crack and some bitonal murmurings from the piano, the second given to the horn and punctuated by wood-block, while the piano constantly tries to subvert the music to its own improvisational ends. Finally, however, the soloist launches a cadenza based upon part of the second theme, and the movement careers to its close in a kind of brassy unity.

The finale is even more concise and more brilliant, grounded in a moto perpetuo for the piano which might have been derived from Saint-Saëns, but serves here as the platform for a sequence of almost surreal musical images, while the orchestra’s opening staccato chords function throughout as a kind of returning figure.

The second movement, though, is the heart of the concerto. Its opening rapt solo for the piano was based, ‘bar by bar’, Ravel said, upon the Larghetto of Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet; but here the effect is more akin to an enchanted nocturne, which gradually draws the instruments of the orchestra into its spell, reaches a climax, and then restates its opening material, this time with the cor anglais taking the melody and the piano supplying a relaxed accompaniment.

INTERVAL – 20 minutes

There are bars on all levels of the Concert Hall; ice cream

can be bought at the stands on Stalls and Circle level.

The Barbican shop will also be open.

Why not tweet us your thoughts on the first half of the

performance @londonsymphony, or come and talk to

LSO staff at the Information Desk on the Circle level?

ALLEGRAMENTE

ADAGIO ASSAI

PRESTO

SIMON TRPČESKI PIANO

The two concertos for piano, this one in G major, and the Concerto in D major for the Left Hand, were Ravel’s last major scores and evolved in parallel between 1929 and 1931. The work for left hand was prompted by a commission from the Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had been injured in World War I, but Ravel appears to have begun the Concerto in G major simply because he wanted to write a work for French pianist Marguerite Long, who had championed his solo pieces. And perhaps it was in meeting the special technical challenges of the left-hand concerto with a dark, slightly forbidding piece, that he had felt the need to provide it with a light-hearted, neo-Classical counterpart.

Certainly, the G major Concerto conveys nothing if not a brilliant jeu d’esprit, a beautifully crafted piece, thoroughly pianistic and immaculately written for the soloist, which nevertheless acquires the character of a divertissement. Ravel revealed something of his intentions in an interview given at the time of its composition: it was to be, he said, ‘a concerto in the true sense of the word. I mean it is written very much in the same spirit as those of Mozart and Saint-Saëns. The music of a concerto, in my opinion, should be light-hearted and brilliant, and not aim at profundity or at dramatic effects’.

Elsewhere Ravel admitted that jazz had been a primary influence, appearing most strikingly in the Concerto’s outer movements, with their blues-inflected sideslips and syncopations. Both these movements, though, are strongly anchored in

RAVEL AND JAZZ

Ravel was fascinated by jazz, with his

enthusiasm strengthened by the four-

month tour of North America that he

undertook in 1928, which took him to

25 cities, including New Orleans, and

brought him into contact with leading

musicians and composers including

George Gershwin. He stated:

‘The most captivating part of jazz

is its rich and diverting rhythm …

Jazz is a very rich and vital source

of inspiration for modern composers

and I am astonished that so few

Americans are influenced by it’.

-

lso.co.uk Composer Profile 7

Maurice Ravel Composer Profile

Although born in the rural Basque village of Ciboure, Ravel was raised in Paris. First-rate piano lessons and instruction in harmony and counterpoint ensured that the boy was accepted as a preparatory piano student at the Paris Conservatoire in 1889. As a full-time student, Ravel explored a wide variety of new music and forged a close friendship with the Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes. Both men were introduced in 1893 to Chabrier, who Ravel regarded as ‘the most profoundly personal, the most French of our composers’. Ravel also met and was influenced by Erik Satie around this time.

In the decade following his graduation in 1895, Ravel scored a notable hit with the Pavane pour une infante défunte for piano (later orchestrated). Even so, his works were rejected several times by the backward-looking judges of the Prix de Rome for not satisfying the demands of academic counterpoint. In the early years of the 20th century he completed many outstanding works, including the evocative Miroirs for piano and his first opera, L’heure espagnole. In 1909 Ravel was invited to write a large-scale work for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, completing the score to Daphnis et Chloé three years later. At this time he also met Stravinsky and first heard the works of Arnold Schoenberg.

From 1932 until his death, he suffered from the progressive effects of Pick’s Disease and was unable to compose. His emotional expression is most powerful in his imaginative interpretations of the unaffected worlds of childhood and animals, and in exotic tales such as the Greek lovers Daphnis et Chloé. Spain also influenced the composer’s creative personality, his mother’s Basque inheritance strongly reflected in a wide variety of works, together with his liking for the formal elegance of 18th-century French art and music.

COMPOSER PROFILE WRITER

ANDREW STEWART is a freelance

music journalist and writer. He is

the author of The LSO at 90, and

contributes to a wide variety of

specialist classical music publications

PIANO WORKS IN 2015

YUJA WANG (12 & 15 MAR)

Sun 1 Feb 7.30pm BEETHOVEN PIANO CONCERTO NO 3 Webern Passacaglia Brahms Symphony No 2

Nicholas Angelich piano | David Afkham conductor

Thu 12 Mar 7.30pm GERSHWIN PIANO CONCERTO IN F MAJOR Colin Matthews Hidden Variables Shostakovich Symphony No 5

Yuja Wang piano | Michael Tilson Thomas conductor

Sun 15 Mar 7.30pm SHOSTAKOVICH CONCERTO NO 1 FOR PIANO, TRUMPET AND STRINGS Britten Four Sea Interludes Sibelius Symphony No 2

Yuja Wang piano | Michael Tilson Thomas conductor

Thu 2 Jul 7.30pm BRAHMS PIANO CONCERTO NO 1 Dvořák The Wild Dove Dvořák The Golden Spinning Wheel

Krystian Zimerman piano | Sir Simon Rattle conductor

020 7638 8891 | lso.co.uk

-

8 Programme Notes 25 January 2015

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) Symphony No 4 (1899–1900, rev 1901–10)

1

2

3

4

the oxen’. A moment or two earlier we catch a glimpse of ‘the butcher Herod’, on whose orders the children were massacred in the Biblical Christmas story.

What are images like these doing in Heaven? Apart from its ambiguous vision, this song-movement also offers one of the most original and satisfying solutions to the Romantic symphonists’ perpetual ‘finale problem’. It couldn’t be less like the massive, all-encompassing finales many composers had struggled to provide in the wake of Beethoven’s titanic Fifth and Ninth Symphonies. Interestingly Mahler wrote this movement before he’d written a note of the preceding three. It was one of several settings of poems from the classic German folk collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn (Youth’s Magic Horn) Mahler had composed in the 1890s. At one stage Mahler thought of including it in his huge Third Symphony; but then he began to see it as more clearly the ending of his next symphony, the Fourth.

Even then, as we have seen, Mahler’s ideas changed as the new work took shape. At first he was thinking in terms of a ‘symphonic humoresque’, but then the ideas took on a life of their own and the symphony ‘turned upside down’. In its final form, the first three movements of the Fourth Symphony prepare the way for the closing vision of ‘Das himmlische Leben’ on every possible level: its themes, orchestral colours, tonal scheme, most of all that strange emotional ambiguity – blissful dream touched by images of nightmare. Far from being Mahler’s simplest symphony, it is one of the subtlest things he ever created.

First Movement The very opening of the Fourth Symphony is a foretaste of the finale. Woodwind and jingling sleigh-bells set off at a slow jog-trot, then a languid rising

BEDÄCHTIG. NICHT EILEN (DELIBERATE. NOT HURRIED) –

RECHT GEMÄCHLICH (VERY LEISURELY)

IN GEMÄCHLICHER BEWEGUNG. OHNE HAST

(AT A LEISURELY PACE. WITHOUT HASTE)

RUHEVOLL (RESTFUL)

SEHR BEHAGLICH (VERY COSY)

KAREN CARGILL MEZZO-SOPRANO

In 1900, just after he’d finished his Fourth Symphony, Mahler wrote about how the work had taken shape. He had set out with clear ideas, but then the work had ‘turned upside down’ on him: ‘To my astonishment it became plain to me that I had entered a totally different realm, just as in a dream one imagines oneself wandering through the flower-scented garden of Elysium and it suddenly changes to a nightmare of finding oneself in a Hades full of terrors … This time it is a forest with all its mysteries and its horrors which forces my hand and weaves itself into my work. It becomes even clearer to me that one does not compose; one is composed’.

Mahler’s remarks about ‘mysteries and horrors’ may surprise some readers. Writers often portray the Fourth as his sunniest and simplest symphony: an affectionate recollection of infant happiness, culminating in a vision of Heaven seen through the eyes of a child – with only the occasional pang of adult nostalgia to cloud its radiant blue skies. But Mahler was too sophisticated to fall for the sentimental 19th-century idea of childhood as a Paradise Lost. He knew that children could be cruel, and that their capacity for suffering was often underestimated by adults. There is cruelty in the seemingly naïve text Mahler sets in his finale, ‘Das himmlische Leben’ (Heavenly Life): ‘We led a patient, guiltless darling lambkin to death,’ the child tells us contentedly, adding that ‘Saint Luke is slaying

PROGRAMME NOTE WRITER

STEPHEN JOHNSON is the author

of Bruckner Remembered (Faber).

He also contributes regularly to BBC

Music Magazine and The Guardian,

and broadcasts for BBC Radio 3

(Discovering Music), BBC Radio 4

and the BBC World Service.

DES KNABEN WUNDERHORN

(Youth’s Magic Horn) is a collection

of over 700 German folk poems and

songs, brought together in the early

19th century by the poets Achim von

Arnim and Clemens Brentano. Mahler

set a number of the poems for voice

and piano or orchestra, and drew

on the texts and his own settings in

many of his symphonies.

-

violin phrase turns out to be the beginning of a disarmingly simple tune: Mahler in Mozartian vein. There is a note of contained yearning in the lovely second theme (cellos), but this soon subsides into the most childlike idea so far (solo oboe and bassoon). Later, another tune is introduced by four flutes in unison – panpipes, or perhaps whistling boys.

After this, the ‘mysteries and horrors’ of the forest gradually make their presence felt until, in a superb full orchestral climax, horns, trumpets, bells and glittering high woodwind sound a triumphant medley of themes from earlier on. But this triumph is dispelled by a dissonance, underlined by gong and bass drum, then trumpets sound out the grim fanfare rhythm Mahler later used to begin the Funeral March of his Fifth Symphony. How do we get back to the land of lost content glimpsed at the beginning? Mahler simply stops the music, and the Mozartian theme starts again in mid-phrase, as though nothing had happened. All the main themes now return, but the dark disturbances of the development keep casting shadows, at least until the brief, ebullient coda.

Second Movement The second movement, a Scherzo with two trios, proceeds at a leisurely pace (really fast music is rare in this symphony). Mahler described the first theme as ‘Freund Hain spielt auf’: the ‘Friend Hain’ who ‘strikes up’ here is a sinister figure from German folk-lore: a pied piper-like figure whose fiddle playing leads those it enchants into the land of ‘Beyond’ – death in disguise? Mahler evokes Freund Hain’s fiddle ingeniously by having the orchestral leader play on a violin tuned a tone higher than normal, which makes the sound both coarser, and literally, more highly-strung. Death doesn’t quite have the last word, though the final shrill forte (flutes, oboes,

clarinets, glockenspiel, triangle and harp) leaves a sulphurous aftertaste.

Third Movement The slow movement is marked ‘restful’, but the peace is profoundly equivocal. Mahler wrote that this movement was inspired by ‘a vision of a tombstone on which was carved an image of the departed, with folded arms, in eternal sleep’ – an image half consoling, half achingly sad, and clearly related to the Freund Hain/Death imagery in the Scherzo. A set of free variations on the first theme explore facets of this ambiguity until Mahler springs a wonderful surprise: a full orchestral outburst of pure joy in E major – the key in which the finale is to end. This passage looks forward and backward: horns anticipate the clarinet tune which opens the finale, then recall the whistling boys’ flute theme from the first movement. Then the movement slips back into peaceful sleep, to awaken in …

Finale … Paradise – or, at least, a child’s version of it. Sleigh-bells open the finale, then the soprano enters for the first time. Possibly fearing what adult singers might get up to if told to imitate a child, Mahler adds an NB in the score: ‘To be sung in a happy childlike manner: absolutely without parody!’. At the mention of St Peter, the writing becomes hymn-like, then come those troubling images of slaughter. The singer seems unmoved by what she relates, but plaintive, animal-like cries from oboe and low horn disturb the vision, if only momentarily. At last the music makes its final turn to E major, the key of the heavenly vision near the end of the slow movement. ‘No music on earth can be compared to ours’, the child tells us. Then the child falls silent (asleep?), and the music gradually fades until nothing is left but the soft low repeated tolling of the harp.

lso.co.uk Programme Notes 9

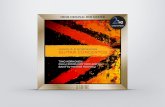

MAHLER on LSO LIVE

Explore Principal Conductor

Valery Gergiev’s critically acclaimed

recordings of Mahler’s nine

symphonies on LSO Live.

Available as downloads, individual

discs or as a 10-SACD box set.

Available at

lso.co.uk/lsolive

in the Barbican

Shop or online at

iTunes & Amazon

MORE MAHLER THIS SEASON

Tue 2 Jun 2015 7.30pm

SYMPHONY NO 5

Edward Rushton new work

Mendelssohn Violin Concerto

Daniel Harding conductor

Janine Jansen violin

Sun 14 Jun 2015 7.30pm

SYMPHONY NO 1 (‘TITAN’)

Mozart Violin Concerto No 3

Bernard Haitink conductor

Alina Ibragimova violin

Part of the LSO International Violin

Festival generously supported by

Jonathan Moulds

020 7638 8891 | lso.co.uk

-

10 Text 25 January 2015

Gustav Mahler Symphony No 4 – Finale: Text

The Heavenly Life

We enjoy the heavenly pleasures and avoid earthly things. No worldly tumult can be heard in Heaven! Everything lives in the sweetest peace! We lead an angelic life! Nevertheless we are very merry: we dance and leap, hop and sing! Meanwhile, St Peter in the sky looks on.

St John has let his little lamb go and the butcher Herod looks on! We lead a patient, innocent, patient, a dear little lamb to death! St Luke slaughters oxen without giving it thought or attention. Wine costs not a penny in Heaven’s cellar; and the angels bake the bread.

Good vegetables of all sorts grow in Heaven’s garden! Good asparagus, beans and whatever we wish! Bowls are heaped full, ready for us! Good apples, good pears and good grapes! The gardener permits us everything! Would you like roebuck, would you like hare? They run free In the very streets!

Das himmlische Leben

Wir geniessen die himmlischen Freuden, Drum tun wir das Irdische meiden, Kein weltlich Getümmel Hört man nicht im Himmel! Lebt alles in sanftester Ruh’! Wir führen ein englisches Leben! Sind dennoch ganz lustig daneben! Wir tanzen und springen, Wir hüpfen und singen! Sankt Peter im Himmel sieht zu!

Johannes das Lämmlein auslasset, Der Metzger Herodes drauf passet! Wir führen ein geduldig’s, Unschuldig’s, geduldig’s, Ein liebliches Lämmlein zu Tod! Sankt Lucas den Ochsen tät schlachten Ohn’ einig’s Bedenken und Achten, Der Wein kost’ kein Heller Im himmlischen Keller, Die Englein, die backen das Brot.

Gut’ Kräuter von allerhand Arten, Die wachsen im himmlischen Garten! Gut’ Spargel, Fisolen Und was wir nur wollen! Ganze Schüsseln voll sind uns bereit! Gut Äpfel, gut’ Birn’ und gut’ Trauben! Die Gärtner, die alles erlauben! Willst Rehbock, willst Hasen, Auf offener Straßen Sie laufen herbei!

-

lso.co.uk Text 11

Should a fast-day arrive, all the fish swim up to us with joy! Then off runs St Peter with his net and bait to the heavenly pond. St Martha must be the cook.

No music on earth can be compared to ours. Eleven thousand maidens dare to dance! Even St Ursula herself is laughing! Cecilia and all her relatives make splendid court musicians! The angelic voices rouse the senses so that everything awakens with joy.

Translation anonymous

Sollt’ ein Fasttag etwa kommen, Alle Fische gleich mit Freuden angeschwommen! Dort läuft schon Sankt Peter Mit Netz und mit Köder Zum himmlischen Weiher hinein. Sankt Martha die Köchin muß sein.

Kein’ Musik ist ja nicht auf Erden, Die uns’rer verglichen kann werden. Elftausend Jungfrauen Zu tanzen sich trauen! Sankt Ursula selbst dazu lacht! Cäcilia mit ihren Verwandten Sind treffliche Hofmusikanten! Die englischen Stimmen Ermuntern die Sinnen, Dass alles für Freuden erwacht.

Traditional text from Des Knaben Wunderhorn

-

12 Composer Profile 25 January 2015

Mahler the Man by Stephen Johnson

Mahler’s sense of being an outsider, coupled with a penetrating, restless intelligence, made him an acutely self-conscious searcher after truth. For Mahler the purpose of art was, in Shakespeare’s famous phrase, to ‘hold the mirror up to nature’ in all its bewildering richness. The symphony, he told Jean Sibelius, ‘must be like the world. It must embrace everything’. Mahler’s symphonies can seem almost over-full with intense emotions and ideas: love and hate, joy in life and terror of death, the beauty of

nature, innocence and bitter experience. Similar themes can also be found in his marvellous songs and song-cycles, though there the intensity is, if anything, still more sharply focused.

Gustav Mahler was born the second of 14 children. His parents were apparently ill-matched (Mahler remembered violent scenes), and young Gustav grew dreamy and introspective, seeking comfort in nature rather than human company. Death was a presence from early on: six of Mahler’s siblings died in infancy. This no doubt partly explains the

obsession with mortality in Mahler’s music. Few of his major works do not feature a funeral march: in fact Mahler’s first composition (at age ten) was a Funeral March with Polka – exactly the kind of extreme juxtaposition one finds in his mature works.

For most of his life Mahler supported himself by conducting, but this was no mere means to an end. Indeed his evident talent and energetic, disciplined commitment led to successive appointments at Prague, Leipzig, Budapest, Hamburg and climactically, in 1897, the Vienna Court Opera. In the midst of this hugely demanding schedule, Mahler composed whenever he could, usually during his summer holidays. The rate at which he composed during these brief periods is astonishing. The workload in no way decreased after his marriage to the charismatic and highly intelligent Alma Schindler in 1902. Alma’s infidelity – which almost certainly accelerated the final decline in Mahler’s health in 1910/11 – has earned her black marks from some biographers; but it is hard not to feel some sympathy for her position as a ‘work widow’.

Nevertheless, many today have good cause to be grateful to Mahler for his single-minded devotion to his art. T S Eliot – another artist caught between the search for faith and the horror of meaninglessness – wrote that ‘humankind cannot bear very much reality’. But Mahler’s music suggests another possibility. With his ability to confront the terrifying possibility of a purposeless universe and the empty finality of death, Mahler can help us confront and endure stark reality. He can take us to the edge of the abyss, then sing us the sweetest songs of consolation. If we allow ourselves to make this journey with him, we may find that we too are the better for it.

I am …

three times homelessa native of Bohemia in Austria

an Austrian among Germansa Jew throughout the world.

-

lso.co.uk Artist Biographies 13

Robin Ticciati Conductor

‘Ticciati was all fire and brilliance and headlong exuberance.’ Rupert Christiansen, The Telegraph

Salzburg Festival, Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin at the Royal Opera House, and a Metropolitan Opera debut with Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, which led to an immediate re-invitation.

Robin Ticciati is in his sixth season as Principal Conductor of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. His 2014/15 season with the SCO features a twin focus on Mahler and Haydn. Together, Ticciati and the Orchestra have toured extensively in Europe and Asia, and their three recordings for Linn Records so far – two Berlioz discs (Symphonie fantastique; Les nuits d’été and The Death of Cleopatra) and a double album featuring Schumann’s four symphonies – have attracted critical acclaim.

Robin Ticciati’s discography also includes Berlioz’s L’enfance du Christ with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra (Linn), Dvořák’s Symphony No 9, Bruckner’s Mass No 3 and a Brahms disc with the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra and the Chorus of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (Tudor) as well as a number of opera releases on Opus Arte and on Glyndebourne’s own label.

Born in London, Robin Ticciati is a violinist, pianist and percussionist by training. He was a member of the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain when he turned to conducting, aged 15, under the guidance of Sir Colin Davis and Sir Simon Rattle. He was recently appointed Sir Colin Davis Fellow of Conducting by the Royal Academy of Music.

Robin Ticciati has been Principal Conductor of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra since the 2009/10 season and Music Director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera since summer 2014.

2013/14 guest conducting engagements included debuts with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, and return engagements with the LSO, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic and Bamberg Symphony Orchestra.

This season Robin Ticciati is undertaking a major residency project at Vienna’s Konzerthaus, featuring performances with the LSO, Scottish Chamber Orchestra and Vienna Symphony. Guest conducting projects within the next two seasons include a European tour with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, return engagements with the Gewandhaus Orchester Leipzig, Staatskapelle Dresden, Swedish Radio Symphony, London Philharmonic, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra and Los Angeles Philharmonic, as well as debuts with the DSO-Berlin, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Czech Philharmonic, NDR Hamburg and Orchestre National de France.

For his first season as Music Director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Robin Ticciati conducted new productions of Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier and Mozart’s La finta giardiniera. In 2015, he will conduct a new production of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail and a revival of a Ravel double-bill with L’heure Espagnole and L’enfant et les sortilèges. Aside from Glyndebourne, recent opera projects have included new productions of Britten’s Peter Grimes at La Scala Milan, Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro at the

Principal Conductor

Scottish Chamber Orchestra

Music Director

Glyndebourne Festival Opera

-

14 Artist Biographies 25 January 2015

Simon Trpčeski Piano

‘There’s a grand romanticism about Trpčeski’s interpretations, as well as an attention to detail.’ BBC Music Magazine

The 2014/15 season includes regular visits to London and return appearances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Seattle, Baltimore and St Louis Symphonies, Minnesota Orchestra, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, Russian National Orchestra, St Petersburg Philharmonic, Armenian Philharmonic, Barcelona and Galicia Symphonies, Strasbourg Philharmonic, Orchestra of the Teatro Regio in Turin, Ulster Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Suisse Romande Orchestra and Iceland Symphony. In the summer of 2015 he also undertakes a tour of Australia and New Zealand with Vasily Petrenko.

Trpčeski has received widespread acclaim for his recital recordings on EMI, winning two Gramophone Awards for his first recording in 2002. Most recently, his 2012 recital at Wigmore Hall was released on Wigmore Hall Live, and his 2014 performance will be a forthcoming release. He has made three concerto recordings with conductor Vasily Petrenko and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, showcasing music by Rachmaninov and Tchaikovsky.

Simon Trpčeski has won prizes in piano competitions in the UK, Italy and Czech Republic. Between 2001 and 2003 he was a member of the BBC New Generation Artists Scheme, and in 2003 he was honoured with the Young Artist Award by the Royal Philharmonic Society. In 2009, he was awarded the Presidential Order of Merit for Macedonia, a decoration given to dignitaries responsible for the affirmation of Macedonia abroad. In 2011 he was awarded the first ever title of National Artist of the Republic of Macedonia. With the support of KulturOp, Macedonia’s leading cultural organisation, and the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Macedonia, he works with young musicians to support the country’s next generation of artists.

Macedonian pianist Simon Trpčeski has established himself as one of the most remarkable musicians to have emerged in recent years. He is praised not only for his impeccable technique and delicate expression, but also for his warm personality and commitment to strengthening Macedonia’s cultural image.

Trpčeski is a frequent soloist with the LSO and with the City of Birmingham Symphony, Philharmonia, Hallé, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and London Philharmonic Orchestras. Other engagements with European ensembles include the Royal Concertgebouw, Russian National and Bolshoi Theatre Orchestras, NDR Sinfonieorchester Hamburg, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne, MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra, Tonkünstler Orchestra in Vienna, Danish National Symphony Orchestra and the Rotterdam, Royal Stockholm, Oslo and St Petersburg Philharmonics.

In North America he has performed with the New York and Los Angeles Philharmonics, the Philadelphia and Cleveland Orchestras and the Boston, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Toronto and Baltimore Symphony Orchestras. Elsewhere he has performed with the New Japan, Seoul and Hong Kong Philharmonic, Sydney and Melbourne Symphony Orchestras, and has toured with the New Zealand Symphony. Trpčeski has worked with prominent conductors including Vladimir Ashkenazy, Lionel Bringuier, Andrew Davis, Gustavo Dudamel, Charles Dutoit, Vladimir Jurowski, Lorin Maazel, Sir Antonio Pappano, Vasily Petrenko, Yan Pascal Tortelier, Marin Alsop and Gianandrea Noseda.

A superb recitalist, he has given solo performances in cultural capitals throughout the world, and appears regularly at chamber music festivals.

-

lso.co.uk Artist Biographies 15

Karen Cargill Mezzo-soprano

‘Karen Cargill has a remarkably beautiful voice, full of sunny delicacy and warmth.’ BBC Music Magazine

conductors including James Levine, Valery Gergiev, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Myung-Whun Chung, Bernard Haitink, Sir Simon Rattle and Robin Ticciati. Previous opera highlights have included roles with the Royal Opera, Covent Garden; Metropolitan Opera, New York; and Deutsche Oper, Berlin.

In 2013 Karen was appointed Associate Artist of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. Past performances together have included Berlioz’s The Death of Cleopatra, L’enfance du Christ and Les nuits d’été; Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde; Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder and the role of Béatrice in Berlioz’s Béatrice et Bénedict. Their recent Linn Records recording of Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été and The Death of Cleopatra with Robin Ticciati was chosen as Gramophone’s recording of the month in June 2013.

An early highlight of her career was singing Mendelssohn’s Elijah with Kurt Masur and the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the BBC Proms. Since then, her regular relationships with the BBC Symphony and Scottish Symphony Orchestras have taken her back to the BBC Proms to sing Mahler’s Symphony No 3 and Das Lied von der Erde and Waltraute in Götterdämmerung, as well as Constant Lambert’s The Rio Grande at a ‘Last Night’.

Scottish mezzo-soprano Karen Cargill studied at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, the University of Toronto and the National Opera Studio, London, and was the winner of the 2002 Kathleen Ferrier Award.

Past and future highlights with her regular recital partner Simon Lepper include appearances at Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw Amsterdam, the Kennedy Center Washington and, this season, her New York recital debut at Carnegie Hall, as well as regular recitals for BBC Radio 3. With Simon she recently recorded a critically acclaimed recital of Lieder by Alma and Gustav Mahler for Linn Records.

Concerts in the 2014/15 season include Bach’s St Matthew Passion and Handel’s Messiah with the Philadelphia Orchestra; Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été with the Cleveland Orchestra; Elgar’s Sea Pictures with the Dresden Staatskapelle; Beethoven’s Symphony No 9 with Bernard Haitink and the LSO in June; and Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder with the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra. With the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Karen will sing Mahler’s Symphony No 4, Kindertotenlieder and Das Lied von der Erde, conducted by Robin Ticciati, and the Wesendonck Lieder with Emmanuel Krivine. This year, Karen will make her debut at the Salzburg Festival.

On the opera stage, plans include a return to the Metropolitan Opera, New York to sing Magdalene in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Waltraute in Götterdämmerung for the Canadian Opera Company, and return invitations to The Royal Opera, Covent Garden and English National Opera.

Karen sings regularly with the Boston, Rotterdam, Seoul and Berlin Philharmonic Orchestras, the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, the LSO and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, working with

-

London Symphony Orchestra Barbican Silk Street London EC2Y 8DS

Registered charity in England No 232391

Details in this publication were correct at time of going to press.

Editor Edward Appleyard [email protected]

Photography Igor Emmerich, Kevin Leighton, Bill Robinson, Alberto Venzago

Print Cantate 020 3651 1690

Advertising Cabbell Ltd 020 3603 7937

The Scheme is supported by Help Musicians UK The Garrick Charitable Trust The Lefever Award The Polonsky Foundation

LSO STRING EXPERIENCE SCHEME

Established in 1992, the LSO String Experience Scheme enables young string players at the start of their professional careers to gain work experience by playing in rehearsals and concerts with the LSO. The scheme auditions students from the London music conservatoires, and 15 students per year are selected to participate. The musicians are treated as professional ’extra’ players (additional to LSO members) and receive fees for their work in line with LSO section players.

16 The Orchestra 25 January 2015

London Symphony Orchestra On stage

Your views Inbox

HORNS Timothy Jones Samuel Jacobs Angela Barnes Alexander Edmundson Jonathan Bareham

TRUMPETS Philip Cobb Gerald Ruddock Niall Keatley

TROMBONE Peter Moore

TIMPANI Nigel Thomas

PERCUSSION Neil Percy David Jackson Antoine Bedewi Tom Edwards

HARP Bryn Lewis

FIRST VIOLINS Roman Simovic Leader Tomo Keller Carmine Lauri Lennox Mackenzie Clare Duckworth Ginette Decuyper Gerald Gregory Jörg Hammann Maxine Kwok-Adams Elizabeth Pigram Claire Parfitt Laurent Quenelle Harriet Rayfield Colin Renwick Ian Rhodes Sylvain Vasseur

SECOND VIOLINS David Alberman Thomas Norris Sarah Quinn Miya Väisänen Matthew Gardner Naoko Keatley William Melvin Iwona Muszynska Paul Robson Katerina Mitchell Hazel Mulligan Alain Petitclerc Julia Rumley Helena Smart Robert Yeomans

VIOLAS Edward Vanderspar Gillianne Haddow Malcolm Johnston Anna Green Julia O’Riordan Robert Turner Jonathan Welch Elizabeth Butler Phil Hall Richard Holttum Caroline O’Neill Alistair Scahill

CELLOS Tim Hugh Alastair Blayden Jennifer Brown Noel Bradshaw Eve-Marie Caravassilis Daniel Gardner Hilary Jones Minat Lyons Amanda Truelove Orlando Jopling

DOUBLE BASSES Rick Stotijn Colin Paris Nicholas Worters Patrick Laurence Matthew Gibson Joe Melvin Jani Pensola Benjamin Griffiths

FLUTES Gareth Davies Adam Walker Alex Jakeman

PICCOLO Sharon Williams

OBOES Olivier Stankiewicz Lauren Weavers

COR ANGLAIS Christine Pendrill

CLARINETS Andrew Marriner Chris Richards Chi-Yu Mo

BASS CLARINET Lorenzo Iosco

E-FLAT CLARINET Chi-Yu Mo

BASSOONS Rachel Gough Christopher Gunia

CONTRA BASSOON Dominic Morgan

Benjamin James Still buzzing after last night’s concert with #SimonRattle, @HanniganBarbara and the tremendous musicians of the @londonsymphony #WorldClass on Thu 15 Jan, with Sir Simon Rattle & Barbara Hannigan

David Todd Incredible playing last night from the @londonsymphony with Simon Rattle. It took hours to recover from The Rite of Spring – terrifying! on Thu 15 Jan, with Sir Simon Rattle & Barbara Hannigan

Paul C Roberts Fantastic concert last night at The Barbican. For me the highlight was the Ligeti, but I loved the intensity of the Webern. on Thu 15 Jan, with Sir Simon Rattle & Barbara Hannigan

Tom Seligman Barbara Hannigan and Ligeti: ten minutes of absolute performing genius! Never to be forgotten! on Thu 15 Jan, with Sir Simon Rattle & Barbara Hannigan