LEGRAS Arguedas Bhabha Etc

-

Upload

mari-alter -

Category

Documents

-

view

56 -

download

10

description

Transcript of LEGRAS Arguedas Bhabha Etc

South Atlantic Quarterly 106:1, Winter 2007 doi 10.1215/00382876-2006-016 © 2007 Duke University Press

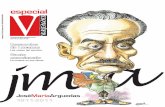

Horacio Legrás

Impertinence

In The Location of Culture, Homi Bhabha ex- presses his belief that “the encounters and ne- gotiations of differential meanings and values within ‘colonial’ textuality, its governmental dis-courses and cultural practices, have anticipated, avant la lettre, many of the problematics of signi-fication and judgment that have become current in contemporary theory—aporia, ambivalence, indeterminacy, the question of discursive clos- ure, the threat to agency, the status of intention-ality, the challenge to ‘totalizing’ concepts, to name but a few.”1 Bhabha connects these critical concepts to colonial experiences in an essay aptly entitled “The Postcolonial and the Postmodern.” All the items listed by Bhabha fall essentially into two big categories: that of language (aporia, inde-terminacy), and that of subjectivity (the threat to agency, the status of intentionality). Newness and emergence also appear frequently in Bhabha’s work, even though he remains sus-picious of a critical approach that would favor issues of origin, force, and becoming. This reluc-tance separates Bhabha’s production from the main concerns of subalternism. While the sub-alternists’ language strives to understand its topic in terms of irruption and insurgency, Bhabha’s

�6 Horacio Legrás

prefers conceptual tools such as displacement and ambivalence to deal with the fragmented experience of a postcolonial modernity. The subalternist acknowledges that subalternity is mediated and constituted as a discursive effect; but he or she must also acknowledge the pressure that the subaltern exerts on the historical text or the police record where its figure appears inscribed for the first time. The status of the subaltern’s irruption remains ambiguous. It is recorded in terms of violence by the dominant social con-figuration, but the subalternist must strive to understand this irruption as a modality of force. The discourse of the aesthetic also ties the question of origins and emer-gence to the issue of force. There is little doubt that the centrality of rep-resentation throughout modernity has resulted in a certain conflation not only of the question of aesthetic and political representation, but also of poetic force and social emergence. An exemplary instance of this rela-tionship appeared with the publication of “Appeal to Some Intellectuals,” a poem by the bilingual (Quechua-Spanish) and bicultural Peruvian writer José María Arguedas. In this poem, Arguedas invokes the power of poetry in his confrontation with a reductionist postcolonial violence. Much to our surprise, perhaps, Arguedas’s negation takes neither the form of an ethical claim of singularity based on difference and identity nor the appearance of a poststructuralist deconstruction of an imperial, Eurocentric logos. Instead, he seeks to challenge the violence of domination by recourse to a lived world that is posited as the unavoidable substratum of any social or historical edifice. This declaration of the primacy of the world recalls the phenomenological intervention that colored the anticolonial pages of Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Memmi, or Maurice Merleau-Ponty. The intimacy between the language of phenomenology and the problematic of postcolo-niality has largely been forgotten today. In the long run poststructuralism displaced phenomenology as the ground from which to think the colonial and the postcolonial relationship. Text, ambiguity, and aporia replaced reduction, valuation, and intentionality as conceptual means of under-standing the coordinates of the postcolonial experience, and even the pri-mordial phenomenological language was rewritten in a poststructuralist logic of the sign. Thus, for Bhabha even “intentionality and purpose . . . emerge from the ‘time-lag,’ from the stressed absence that is an arrest, a caesure of time.”2 The phenomenological tone has not been altogether banished, however, and can be detected not only in Arguedas’s poem but also in some critical inflections of contemporary theory. In this essay, I

Impertinence �7

want to interrogate this convergence of poetics, a phenomenological style of interrogation, and the poststructuralist framework that dominates dis-cussions of postcoloniality. What interests me above all is how these three discourses—poetics, phenomenology, and poststructuralism—tackle the problematic status of force today.

Immemorial Landscape and Historical Time

Arguedas’s poems and novels are never just poems and novels; they also function as theoretical interventions, lending his books an aura of proph- ecy and insight. One of the strongest of these interventions was the 1966 Spanish-Quechua poem “Llamado a unos doctores” (“Appeal to Some Intel-lectuals”).3 The poem is directly related to a public debate that took place at a roundtable organized by the Peruvian Institute of Literature following the publication of Arguedas’s novel Todas las sangres in 1964.4 Arguedas had characterized his novel not only as an instance of realism but also as a testimonial of indigenous and mestizo life in the Andes. The participants at the roundtable, however, criticized the novel as nothing but the wistful portrayal of a bygone society. The disagreement centered around the question of how to characterize the popular element of Andean societies. For Arguedas, this popular element was indigenous in its worldview and upbringing. For the social scientists, the only valid category with which to address the popular strata of Peru was that of the peasant; their worldview could be understood only according to the issues forced upon them by the modernizing and exploitative dynamic of a regional form of capitalism. This tension regarding the identity of the popular (more cultural and autonomous in Arguedas, more socioeconomic and reactive in his readers) was coupled with a no less dramatic disagreement around the nature and goals of literary discourse. Commentators at the roundtable charged Arguedas with incarnating a reactionary position. Salazar Bondy regretted that the sympathies of the author did not lie with the character that in his view represented a “progressive step” (27). José Miguel Oviedo lamented the fact that the Indians sided with the traditional and reactionary land-owner in his conflict with the innovative, greedy, and unscrupulous “na-tional industrial.” Not only did this seem “confusing” to Oviedo; it would, he thought, “confuse” the readers as well (34). Rather surprisingly, both Salazar Bondy and José Miguel Oviedo claimed that they were expressing not so much a personal opinion as a “sociological standpoint” (27, 34).

�� Horacio Legrás

Meanwhile, those who sided with Arguedas in the debate called for a “literary reading” of the novel, where the expression literary reading was opposed to a “naive,” referentialist ideology of the artistic work. They did not notice that depriving Arguedas’s fiction of the claim of being inextri-cably linked to reality amounted to condemning it to irrelevance in his view. The truth is that the unskilled literary reader, sociologist, or anthropologist who measured Arguedas’s novel by the parameters of “reality” were not wrong, not even from a properly “theoretical” point of view. Arguedas’s literature had always addressed the status of the real in a context so fis-sured along linguistic, ethnic, and cultural lines that it constantly ruined the claims for stability made by any hegemonic discourse. “Appeal to Some Intellectuals” is more than an answer to the arrogance of the intellectual. It is also a liminal text that looks ahead to Arguedas’s last, unfinished novel, The Fox from Up Above, and the Fox from Down Below—a text, in Alberto Moreiras’s words, “powerful enough to arrest our world and any world.”5 This process of arresting a world, which clearly sets The Fox apart from all of Arguedas’s previous production, is already the most noticeable feature of the poem. In this composition, Arguedas was no longer concerned with the identity of the Andean people as in his pre-vious works; rather, he was concerned with the world as the very ground for the adjudication of social and historical identity. This move incarnates the postcolonial enunciative position in an exemplary way insofar as its most immediate result is to reawaken the original epistemic and linguistic violence that is foundational to the colonial relationship. But Arguedas insists not on the aporetics of language or on the deidentificatory nature of subjection, as in a postmodern version of postcoloniality, but rather on embodiment. Already at the roundtable, the Peruvian writer had rejected the possibility of a disembodied vision of the Andes with such vehemence and coherence that we must read it in programmatic, rather than acciden- tal, terms: “I have to tell it as it was, because I enjoyed it, I suffered it” (18). The phrase links a claim of objectivity to a factual commitment—to use the old existentialist expression—of the author to his world. Such a link leads to a form of realism which, as Cornejo Polar noticed, is both a description and an interpretation of reality.6 It is a form of realism based not so much on observation and detachment as on the intensity of a lived experience. Is admitting a lack of “objectivity” a self-defeating strategy? Arguedas would perhaps have answered that any narration, and not just his narration, tes-tifies to a relationship of joy or suffering with the world. He surely enter-tained and dismissed the possibility of a disembodied knowledge of the

Impertinence ��

world—a knowledge performed by nobody upon an object that has become indifferent, almost nothing. This thought may have terrified him, and a good deal of his literature seems to arise in answer to this possibility.

The Value of the World

The poem’s opening lines read:

They say that we no longer know anything, that we are backward, that they will exchange our heads for better ones.

They also say that our heart is not in tune with the times, that it is full of fears, of tears, like the heart of the calandria, like the heart of a great bull whose throat is cut, and for this we are considered impertinent. (253)

The poem starts by conceding a dominant position to the intellectuals: that of “common sense,” that of “the said.” Some intellectuals, some doctores, the poem says, think the Indians are unfit for the times. The developmen-talist ideology that underpins the discourse of the intellectual is evoked through words that connote the movement of a historicist modernizing discourse (no longer, backward, not in tune with the times). But Arguedas denies this position epistemic authority. The deep collusion of morality and developmentalism is made blatant by the use of a word such as impertinent to refer to the intellectual’s reaction to the endurance of an indigenous worldview. Yet as the poem unfolds, the boundaries between the rational discourse of the intellectual and the traditional mythic discourse of the Indian poet whose worldview is under siege starts to break down. The intel-lectuals say (but in a language that robs them of their language) that the Indian’s heart “is full of fears, of tears, like the heart of the calandria, like the heart of a great bull whose throat is cut.” Arguedas’s goal is to put an end to this pretension of the intellectual to explain the world and appropriate the other’s point of view, correcting his or her impertinence. The resistance to appropriation, however, comes not through an affirmation of the ethical right of the indigenous voice to define its own social being , as we might expect, but rather by opposing the pre-tension of the intellectuals to the rock face of lived reality. “[Let them speak then],” the poet challenges the doctores; and he immediately asks:

What is my brain made of ? What is the flesh of my heart made of ? The rivers run roaring in the deep. The gold and the night, the silver

�0 Horacio Legrás

and the frightening night create the rocks, the walls of the canyon where the river sounds; that rock is the matter of my mind, my heart, my fingers. (253)

Arguedas challenges the doctores on a terrain which they call theirs but which they have, in a remarkable lapse of attention, perhaps forgotten: the ontological ground of reality. This movement toward a primordial understanding of the being of the world appears forcefully expressed in an otherwise nonsensical question: “What is the flesh of my heart made of ?” The knowledge of the intellectuals may not be false from a scientific point of view, but it is alienated knowledge. Thus the question-accusation: “What is there on the riverbank of those waters you do not know doctor?” The intellectuals own the word, but they are foreign to the land of which they speak, because they are foreign to every land. Scientific knowledge is obtained through a renunciation of worldly experience. The Andean world is not, however, closed to the gaze of the intellectual. Arguedas challenges them to use all the potency of their vision: “Bring out your spyglass, your best glasses. See, if you can” (253). Seeing, mere seeing, does not grant knowledge because knowledge itself has become a form of blindness. Seeing avoids its fate as blindness when it incarnates a real, active power of defamiliarization that we associate with the life of aesthetic forms but that Arguedas, in his poem, locates in a sphere more primal than that of the aesthetic. There was a time when theory, too, was radical in its orientation. Merleau-Ponty, to name the most prominent member of this school of radicalism, also indicted science and theory for “the eagle’s gaze,” the lofty, removed view that cannot engage the thickness of the world but rather consoles itself by producing a substitute reality. For Merleau-Ponty, the phenomenological reduction invites us to return to a world “which pre-cedes knowledge, of which knowledge always speaks, and in relation to which every scientific schematization is [abstract] . . . as is geography in relation to the countryside in which we have learnt beforehand what a forest, a prairie or a river is.”7 Against the abstract knowledge of the sci-entist Merleau-Ponty proposed a disalienated experience of the world. In a passage from The Visible and the Invisible, he phrases this experience in the following terms: “The effective, present, ultimate and primary being . . . offer themselves . . . only to someone who wishes not to have them but to see them, [to someone] who is therefore not a nothingness the full being

Impertinence �1

would come to stop up, but a question consonant with the porous being which it questions and from which it obtains not an answer, but a confir-mation of its astonishment.”8 Not only does Arguedas’s poem echo these contemporary pages of Merleau-Ponty; in addition, at a critical juncture the poetic voice asks: “Is the world without value, my friend, my doctor?” The word value is more enigmatic than it appears at first sight. It is a value consonant with the arising of humanity itself. Unsurprisingly, value is a critical word in the language of the phenomenologists as well (unsurprisingly because, as Merleau-Ponty put it, phenomenology is not a school, but an attitude as old as the world itself ). Value is the word through which the phenomenologist reminds his or her reader that phenomenology is not a psychologism. Reduction does not lead back to the utopian moment of an “objective and distinct” perception. The active side of the intentional act is a donation of meaning. For Merleau-Ponty, this initial value of the world is, as we already saw, astonishment. Likewise, Arguedas’s literature confronts its reader with the problem of the value-forming activity of the indigenous, subaltern people of Peru; however, the gesture, repeated novel after novel, always remained difficult to read. But what about us? Can we today think value? Can we think of value, as Arguedas does, outside the sphere of a juridical-moral purview? Can we restore its connections with the dimension of cre-ation, production, and originality that, Agamben tells us in the last aesthetic of the twentieth century, even today constitutes the basis of art’s promise of a disalienated human habitation of the world?

Roots and Breaks

The difference between the phenomenological style of interrogation (the one that comes closest to the anticolonial discourse incarnated in Argue-das’s poem) and the poststructuralist one (the one favored by transnational postcolonialism) reveals itself fundamentally as a difference in orientation. Reduction, Husserl reminds his reader somewhere in his copious work, comes from the Latin reducere, leading back, going back. The radicalism of phenomenology is literal, even if, unlike contemporary theory, it never leads us back to the letter. It is a regressive radicalism, opposed to the forward movement that characterizes theory, and, more precisely, post-colonial theory today. We are used to thinking the postcolonial along with other “posts,” namely the poststructural (from which, Ranajit Guha tells

�2 Horacio Legrás

us, the subalternists drew the essential tools of their critical apparatus) and the postmodern (somewhat equated by Homi Bhabha to the postcolonial). As we saw in the quote from Bhabha that opened this essay, the issues that most concern the researcher in these modalities of the postmodern, the postcolonial, and the poststructural are issues of language and subjec-tivity, in an arrangement in which the intrinsic ambivalence of the first bequeaths the sign of its uncertainty to the second. Yet it is also the same Bhabha who, when retracing the intellectual path taken by a primordial figure such as Frantz Fanon, will recall the instrumental role played by a phenomenological style of interrogation in the key arguments of Black Skin, White Masks. Fanon, Bhabha tells us, splits his critical energy into three discourses—Marxism, phenomenology, and psychoanalysis—and puts phenomenology to work in an attempt to restore “the presence of the marginalized” (Location, 41). This reference is brief but critical. Since the beginning, phenomenology appears tied to the question of acknowledging the presence of an outside, registering the irruption of a force into the careful check and balances of a well-ordered hegemony. A postcolonial theory heavily influenced by poststructuralism and de- construction makes irony, the literalization of the law, or the play of identi-fication and disidentification the cornerstones of its emancipatory strategy. The Western values of reason and universalism are not rejected but used with the knowledge that their claim to universal validity is flawed. They are used against the West, as regulating ideas able to show how an imperial logos cannot unfold without contradicting its own core.9 One wonders if this strategy can survive the increasing domain of what Peter Sloterdijk calls “cynical reason.” One also wonders up to what point a strategy based on irony does not presuppose the self-division of the modern European sub- ject rather than an objective structure created by the colonial relationship (such would be Bhabha’s position). We know, for instance, that irony is a rhetorical weapon completely unavailable to a writer such as Arguedas, whose characters only experience self-division, as Creon or Oedipus did two millennia before, under the form of destiny’s curse. Under the current shape of dominance, which relies on cynicism (Sloterdijk), patronizing benevolence (Žižek), or the denial of coevalness (Johannes Fabian), Argue-das’s poem reminds us that the phenomenological reduction, with its pos-sibility of suspending the posited world, remains a formidable political weapon. Even more, as I will argue more explicitly later, there seems to be an elective affinity between literature as an aesthetic force and the recourse to the reduction of the world as a postcolonial strategy of sorts.

Impertinence ��

If the phenomenology of culture has always constituted a relevant politi- cal tool for disassembling established hegemonies, how can we explain phe-nomenological discourse’s plunge in the stock market of critical discourses? The criticism of phenomenology is far from being a recent development. Some of the core propositions of phenomenology were already under siege in Husserl’s lifetime. Husserl attempted to reground European science by bringing the essence of the thing into the sphere of absolute immanence. The phenomenological method intended this essence under the modality of absolute presence (a Selbstgebung, self-giving).10 Already in the late 1920s, Heidegger’s philosophy had made some dents into the possibilities announced so pompously by Husserl. The subject cannot constitute the world, because it arrives into a world that is already constituted. In Being and Time, the formative attributes of the Husserlian transcendental subject appeared to be eclipsed by the disoriented humility of a fallen Dasein. In the 1960s, subsequent and conclusive blows came in the shape of the early work of Jacques Derrida. In 1962 Derrida translated and wrote an extensive introduction to Husserl’s The Origin of Geometry. In 1967, he published Speech and Phenomena, a deconstructive reading of Husserl’s Logical Inves-tigations. Phenomenology again played a critical role in Derrida’s first three important books of the late 1960s and early 1970s: Writing and Difference (which contains a whole revised version of “ ‘Genesis and Structure’ and Phenomenology,” which Derrida had presented at a conference in 1959), Margins of Philosophy, and Of Grammatology. One of the main targets of Derrida’s criticism was the logic (as much as Husserl disliked the word) implicit in the reduction and the dependence of that logic on an intuition based on the modality of the presence of the eidos. Derrida’s notion of dif-férance, in contrast, underlined the deferred character of all possible logical operations. But more important, Derrida faulted phenomenology for not delivering on its promise of a genetic investigation and instead canceling the genetic moment with dogmatic recourse to a structure. Finally, in the 1980s (but this enumeration does not pretend to be exhaustive), Slavoj Žižek launched an attack on the genetic pretensions of the phenomenological exploration of the development of a human sphere from his logical-structuralist interpretation of the Lacanian inheritance. In “Cartesian Subject versus Cartesian Theater,” Žižek discards the possibility of a reduction to a prereflective—understood by him as prelinguistic—state of being.11 His argument follows the style of the clear-cut structuralist and antigenetic articulation. As described by Mladen Dolar, this strategy recognizes that “structure always springs up suddenly, from nothing,

�� Horacio Legrás

without any transitional stages.”12 For Žižek the structure in question here is the symbolic as the operator that severs the human link to nature and ruins any explanation of a genetic passage from a naturelike stage to a culturelike stage. “There is no subjectivity,” writes Žižek, “without [a] gesture of withdrawal . . . the withdrawal-into-self, the cutting-off of the links to the environs, is followed by the construction of a symbolic universe that the subject projects onto reality as a kind of substitute-formation.”13 Through the development of such critique (and, no doubt, with the con-tribution of others, like feminism and post-Marxism) a certain common sense of contemporary criticism crystallized in the 1980s and 1990s. Any genetic investigation, any investigation of origins, transformations, and beginnings, is suspect of harboring a form of essentialism, of ontologizing what is in fact no more than a discursive effect. It was Žižek himself who articulated theory’s unease regarding this situation in the most forceful manner, when, in the context of a discussion with Ernesto Laclau, he quotes Wendy Brown on the subject of the repression of radical politics and critical imagination. “To what extent,” Brown asks, is a critique of capi-talism “foreclosed by the current configuration of oppositional politics,” and not simply by the “loss of the socialist alternative” or the ostensible “triumph of liberalism” in the global order?14 Žižek takes the argument further and declares that the main question of “today’s philosophic-political scene” lies in the impossibility of imagining any alternative to the ruling capitalist order, a situation that he diagnoses in terms of an inability to think the dimension of the act. We live, he continues, under an “unwritten Denkverbot (prohibition to think)” whose result is that “the moment one shows a minimal sign of engaging in political projects that aim seriously to change the existing order . . . one is met with a disarming benevolence and an outright resistance towards even thinking an act.”15 Arguedas’s reaction against the critique of the social scientists echoes the situation described by Žižek in this paragraph. An ominous Hegelian pronouncement comes to mind: the end of his- tory. Is the systemic nature of society, which, pace Žižek, the Lacanian no- tion of the symbolic did a lot to sediment, the theory of the subject at the end of all things? Are origin and change impossible in a world that has exhausted—to say it in phenomenological fashion—all variations and in which history stands unmoved in complete nakedness? Or is it rather that we are ill equipped to think origin, becoming, and emergence in the grammar of our times? These terms—origin, becoming, force—do not cover,

Impertinence ��

of course, the same phenomena, but they draw up a system of inextricable equivalences. For a postcolonial perspective, origin and originality are the two most important concepts in the series, provided that, by them, one does not understand the impossible moment of pure difference scorned by Borges in some well-known texts, but rather, as Giorgio Agamben shows laboriously in The Man without Content, proximity to the origin: an intimate, inalienable relationship to the cause, and, through the cause, working as a form of poiesis.16 Now, if the origin is always already under the mark of a repetition, in what sense does the phenomenological project hold any interest for an anti-colonial politics? Perhaps, as Derrida contends, phenomenology is unable and unwilling to think the question of the origin.17 Phenomenology, however (but phenomenology is here just a placeholder for a larger desire), wanted to think some of these liminal positions. Where has this desire gone? What place does it occupy in the discourses with which we seek to keep alive what Benjamin called the tradition of the oppressed? Because, if theory does not live in the inheritance of that call, if theory does not serve that purpose, it is difficult to see what purpose it is going to serve and remain a critical theory.

Force of Marx

It is no doubt revealing that Žižek’s tirade against postmodernists, decon-structionists, and “hypocritical liberals” comes in the context of a dis-cussion of the Lacanian act, as the action able to change the coordinates of the symbolic. This act is Žižek’s favorite tool to think social change in a way that remains heavily structuralist (society as a structure changes due to a cause that hits it from “outside,” so to speak). The obvious problem with this approach is the blindness entailed by the movement, and this despite the fact that the act, as Žižek reminds us, “retroactively produces grounds which justify it.”18 But it is not a matter of disqualifying the act, so much as recognizing in its blindness the problematic status of force in contemporary thinking and its imperfect repression in the decorum that dominates the academic debate at times. The foreclusion of the act takes the form, Žižek says, of a Denkverbot, a prohibition to think. Although foreclusion is too strong a word, it is perhaps the same barrier against which “the argument”—for lack of a better word—of Specters of Marx unfolds. In this book, Derrida tells us that

�6 Horacio Legrás

the real antagonism is one between praxis (but he doesn’t say praxis, he says force) and the “neutralizing anesthesia of a new theoreticism” (Specters, 32). As theory lapses into contemplation, it lives in the silent assent, the tacit consent—as Gramsci would put it—to the existent and to the power structure that characterizes it. There has been much debate about how to interpret Derrida’s call for a renewed fight against the deep-rooted theo-reticism of theory. Is the call a moment of voluntarism that falls outside the strict conditions that define the “Derridean corpus”? (Derrida himself leaves the door open for this reading on page 32 of Specters.) Ahijaz Ahmad sees in Specters an attempt to use the prestige of deconstruction to high-light the vitality of a besieged tradition. Terry Eagleton reads it as a proof of the irresistible attraction the peripheral exerts on the deconstructionist ethos.19 There are also those who read the book as the instantiation of a philosophical break, a sudden urge to talk about Marx and, through Marx, about politics, power, and hope. Such a break was announced, we read, by Derrida’s increasing engagement with Levinas’s ethics and confirmed by the appearance of texts like For Nelson Mandela. Personally, I think that Specters of Marx is a much more “conservative” book than these commen-tators invite us to believe. Even the oft-quoted assertion that for Derrida deconstruction hardly holds any interest except as a radicalization of a certain spirit of Marxism (Specters, 92) should perhaps be read not in the personal-ethical sense in which it has been read so far but in the literal, phenomenological spirit of radicalization as reduction, as leading back to an ontogenesis of the world. Of course, it will be difficult to prove this point. Derrida’s aversion to a discourse of origins will conspire against it, and so will the inadequacy of our critical language to name this performative moment of origination without confusing it with an instance of teleological origin—what Derrida calls the question of the event as the question of the ghost (Specters, 10). The fact that Specters, like so many of other Derrida’s texts, is not a very bookish book also conspires against the possibility of reading it in reference to the much more stable body of Marxist tradition. Specters of Marx is a book in which not all the claims can be wholly articulated, made commensurable to each other. It is a book through which Derrida catches up with Levinas and, along with Levinas, with the discourse of phenome-nology, with certain imprudent moments of Heidegger, with a renovated attention to emergences, beginnings, and survivals (that identify a certain Marxist discourse as well), and finally with Derrida’s intellectual history

Impertinence �7

itself. Its structure is perhaps best grasped under the Heideggerian rubric of the gathering, of the tension between juncture and disjuncture (diké and adikia), so correctly used by Fredric Jameson as one of his keys for reading the text (Ghostly, 41).The book’s figure would be a disjunctive gathering, an attempt “to maintain together that which does not hold together” (Specters, 17). And although this (not) holding together pertains to the structure of historical temporality as much as to the structure of temporalization, it grasps, as Antonio Negri’s interpretation claims, an essential change in the modalities of production and subjection of late capitalism: the vanishing ontology of work that is displaced by the ghostly consistency of the work of the general intellect.20 However, Specters bears a Heideggerian mark not because “gathering” can work as a figure of its composition (an obser-vation that, by and large, remains banal), but because truth is, here more than ever, the result of a struggle. Juncture and disjuncture only hold their places in their simultaneous reference to the struggle, which in terms of the book is elucidated as an ontophenomenology of force. Force, the thinking of origin, was never alien to Derrida’s work. His interest in the issue is already apparent in the 1967 essay “Force and Signi-fication,” but colored by a pessimistic tone and an ambiguous relationship to the structuralist event. Already on the second page of the essay one finds this assertion: “Form fascinates when one no longer has the force to understand force from within itself. That is, to create” (4). And then, after establishing the unbreakable link through which structuralism receives the whole weight of the Western metaphysical tradition from phenome-nology, Derrida goes on to write: “One would seek in vain a concept in phenomenology which would permit the conceptualization of intensity or force” (27). The impossibility of thinking force marks phenomenology’s (and consequently structuralism’s) return to Platonism. Is, then, a thinking of force (a word determined, at this stage, only by its opposition to form) the key to a break with Platonism? And if this is true, how could the project of deconstruction develop without turning toward this question? In 1967, force makes its way back into Derrida’s thought through his engagement with Levinas’s philosophy. In the essay “Violence and Metaphysics,” also contained in Writing and Difference, Derrida confronts the remnants of metaphysical pretensions inhabiting Levinas’s ethics of otherness with phenomenological convictions in order to show that the rights of the here and now depend on what, many years later, he will call a paradoxical phe-nomenality.21 “Violence and Metaphysics,” which arises from a reading of

�� Horacio Legrás

Totality and Infinity, does not contain any distinction between violence and force. It is only after the publication of Levinas’s Otherwise Than Being, with its refined notions of trace and the distinction between said and saying (a distinction, however, that was available to Derrida through the oppo-sition between “call” and “naming” in Levinas’s 1951 essay “Is Ontology Fundamental?”), that Derrida will recognize in speech and performativity a socially constitutive force that can be separated from the instances of power. This equation will in turn lead to the formula “Deconstruction Is Justice” in an essay in which force itself makes the headlines: “Force of Law.” If force has always been part of the horizon of deconstruction (as the pro-motion of questions such as those of the gift, the es gibt as original opening, the identity between force and justice, and the increasing concern with performativity may attest), how can one ignore, on the other hand, that Specters of Marx brings a special torsion to this meditation? The structure of supplementarity between deconstruction and Marxism that takes place in this text remains difficult to elucidate, however. Perhaps one of the main obstacles for this elucidation lies in the extended prejudice that the only form of engagement that deconstruction can entertain is that of reading texts. Michael Sprinker spells this attitude out clearly in his introduction to Ghostly Demarcations, when he writes that confronting “head on the rela-tionship of deconstruction to Marxism” is synonymous with “subject[ing] Marx’s texts to the same kind of exegetical rigor that Derrida himself had already brought to bear on those of Plato, Rousseau, Heidegger and many, many others” (Ghostly, 1). In our way of imagining the engagement between deconstruction and Marxism, we want to escape this language of subjecting and subjection. What is the desire, and not just the urgency, that pulls Derrida into the Marxist text? What element inside the deconstructionist project is itself pulled out by the discursive configuration inaugurated by the inheritance of Marx? Like every question about causes, this one will remain, perhaps, impossible to answer. But we can advance in that direction by asking about the grounds on which the encounter of deconstruction and Marxism takes place. The best candidate to fill this position is, of course, the notion of hauntology, with its revelation, as Fredric Jameson put it, that “the living present is scarcely as self-sufficient as it claims to be” (Ghostly, 39). Although he acknowledges the accuracy of Jameson’s characterization, Derrida sees in it a “reduction” of the complexity of hauntology (Ghostly, 267, note 71). Hauntology is more than that, Derrida complains. It refers

Impertinence ��

to the difference between Specter and Spirit and, beyond that difference, to their “articulation” in a relation of différance. But more, here, is simulta-neously less. The stress on the structure of temporalization deemphasizes the weight of the ontological that so fascinates both Jameson and Negri in Derrida’s book. And Jameson’s less is consequently more, because haunt-ology is the meeting ground of deconstruction and Marxism, I want to suggest, only with the condition that we see in it the revelation of a force. And with this condition, the element that can be named the ground of the encounter changes so that the encounter between deconstruction as a thinking of originary force and Marxism as the historical-messianic deter-mination of force happens in fact on the grounds of the concept of work in general. Derrida and the Marxist tradition that he interrogates have two different names for this primordial ground. For Marx, who was writing with the Industrial Revolution rising before his eyes, work (or force) names a particular power: labor power. For Derrida, who writes Specters of Marx at the historical juncture of the neoliberal remodeling of the post-Fordist world, the concept of work in general refers to mourning, which, Derrida tells his reader, is work proper, true work. It would be a complex but worthwhile task to read the Arguedian corpus as a summary of these determinations: the value-positing power of labor, the primary force that subtends any labor power by the sheer fact of its attunement to the world, and finally the work of mourning as the consti-tutive force of the aesthetic drive. A problem arises at this point that is worth at least being mentioned. Benjamin’s eleventh thesis on history speaks of a “corrupted conception of labor” and sees as its attribute the forgetting that labor is in our times always exploitative labor. For Benjamin labor appears already subsumed in the dialectic between monument and barbarism. Der-rida’s notion of labor comes from a more idealistic interpretation of labor as human self-fulfillment. In many of his texts, Arguedas seems to side with the optimistic notion of labor as self-fulfillment. Arguedas does not forget that labor is also a source of alienation, but he believes that there is still a chance to rescue actual, exploitative labor from the realm of alienation by returning the essence of the subject to the dignity of a situation.22 How is the disjuncture between an alienated form of labor and labor as a primordial human activity thought in Derrida’s text? At the his-torical juncture in which Derrida writes his text, which is also the his-torical juncture of Arguedas’s production, the work of mourning is also the mourning of work. This double bind between the work of mourning

100 Horacio Legrás

and the mourning of work maintains the tenuous hope that there will still be a future (“There will be no future . . . no future without Marx, without the memory and the inheritance of Marx” [Specters, 13]). Derrida is talking not about any future whatsoever but about a future that is bound to a past that stands as its original destination. The idea of historical time implicit in this assertion is not the empty homogeneous time of modern temporality. Modern time is precisely never empty and homogeneous in that sense, but rather inhabited by the ghosts of a commanding past. It is in this sense that there is no future without Marx, without a certain specter of Marx. Not, at least, a future that we will still be able to call ours. Like Heidegger, who is the unavoidable reference to this way of thinking temporality, Derrida evokes the structure of inheritance embroidered in our experience of time at a moment of great danger for the inherited past and for the structure of inheritance itself.23 Mourning as true work is the constant, ghostly reemer-gence of work at the moment of its dismissal. This is Derrida’s way of inserting the dimension of promise in a world exhausted not only by the “neutralizing anesthesia of a new theoreticism” but also by the devaluation of production, the banalization of democracy, and the reduction of art and creativity to the parameters of market consumption. Derrida, of course, is not “discovering” these threats; their best formu-lation appeared, more than three decades ago, in Herbert Marcuse’s One Dimensional Man. Arguedas knew them too. Perhaps his whole work is a passionate indictment of the ferocious disenchantment of the world by the logic of developmentalist capitalism. In “Appeal to Some Intellectuals,” and in the story that surrounds its production, we already read the dominant configuration in which the exhaustion of production, a wholesome terri-torialization of creativity, and an anesthetizing theoreticism speak of an arrangement in which the messianic promise of justice, the poietic essence of art and life, and the openness of the political seem to live under a common threat.

The Dimension of the Aesthetic

Arguedas wrote Todas las sangres as a political intervention into the daz-zling struggle that he saw developing before him. At the roundtable, he was called to order in the name of science and a progressive politics. Unable to answer to the charges of the scientist in the language of dissent, he vowed to kill himself in notes drafted two days after the roundtable. Instead he kept

Impertinence 101

writing for a few more years. “Appeal to Some Intellectuals” arose from this postponement of death. But it is difficult for a discourse of force to hold its place in the social arena. “Appeal to Some Intellectuals” is, like death, a retraction into a more elemental dimension of existence. This retraction, it is worthwhile to remember, has its origin in a refusal to grant political validity to the writer’s word. It will be a mistake to think of this suspension of the political as a parochial incident. Even if a suspension of the political is inherent to the colonial situation, the truth is that such a reduction is not an exception anymore, but increasingly the norm everywhere. As politics end—as the dominant politics becomes the foreclosure of the political—the world becomes inhabited by a certain fundamentalism, a tenacity of self-assertion. This tenacity can have all the fragility of market-produced identities or the unsoundable depth of a quasi-mystical affirmation of an endangered singularity. True, Fanon (Bhabha taught us to recognize this fact) “speaks most effectively from the uncertain interstices” (40), such as when he writes: “The Negro is not.” But Fanon also stresses the material, almost unbearable character of the antagonism: the fact of blackness. The fact of blackness is an inextricable, postlinguistic determination—an exis-tential in Heidegger’s terms. The facticity of existence that Fanon ciphered in a color scheme, Arguedas ciphered in the obstinacy of a certain ineradi-cable worldliness in the formation of self, other, and knowledge: “That rock is the matter of my mind, my heart, my fingers.” One can still argue that an opposition commands this fall into literal-ization. What does Arguedas’s assertion of an always-renewable primacy of the world contest? What is the epochal enemy that demands the return of the world? Nihilism? Very likely and even more likely the coupling of nihilism and capitalism. The knowledge of the scientists hovers over the world, as capitalism—says Fernand Braudel in a remarkable insight—hovers over markets and communities waiting for the moment to vam-pirize the surplus of their efforts.24 The knowledge-before-experience of the doctores, like the capitalist appropriation without production, acquires the status of a philosophical-political problem not because they incarnate a developmentalist logic (Arguedas sees nothing wrong with the modern-ization of the Andes) but because they incarnate a nihilistic path that seeks to uproot the material, phenomenal basis of the world’s diversity—because they seek the erasure of the world and its reconstitution in a hegemonized form of surplus knowledge. Although these social conditions should be taken into account in a reading

102 Horacio Legrás

of Arguedas’s poem, we are still confronted with the fact that Arguedas did not use a manifesto or a political statement to denounce the collusion of nihilism and capitalism. The fact that these things are said in a poem changes everything. The epochal encounter of art and negativity endowed the question of originality with a chilling power of dissolution. This power, Agamben recounts in The Man without Content, already inhabited the ancient Greek world. The Greeks experienced the essence of art as Deus phobos, a divine terror in whose name and fear Plato banned the poets from his Republic. But only in modernity, Agamben continues, the artist lends his or her substance to the work. Now, insofar as this substance is consti-tuted by the negation of every and any content, the work of art becomes the site for the exercise of an “annihilating” activity.25 It is precisely because the work of art embodies the magnificent power of the negative that we feel authorized to relate its operation to the philosophical tradition of the negative. The kinship between art and philosophy is, however, limited. The work of art boasts an essential irresponsibility that philosophy can acquire only at the price of the dissolution of the sphere in which it is nourished and in which it evolved. Unlike philosophy, the aesthetic does not recognize any frontiers to its power of dissolution because dissolution itself reigns in its essence. For this reason, we would be grossly mistaken if we ended our reading of Arguedas’s poem with the celebration of an inexhaustible worldliness of the world that opens up a space of originality, a proximity of the work to the activity of its production. It is true that Arguedas privi-leged these ideas in previous works and that this intonation is present in the poem; but this is not its final word. Even if it is true that no subaltern or subordinate position can renounce the possibility of regrounding the world in a different set of values, the fact is, “Appeal to Some Intellectuals” offers no values at all. Arguedas’s brutal reduction of the antagonism to the ground of every possible antagonism implies a certain removal of the anta-gonic logic itself, which is suspended by his particular style of thematizing the ground. This movement, which implies a salutary subtraction of tele-ology, of the fatality of history, after obtaining its presumed goal, keeps going, doing away with all (or almost all) positivity as a storm or a tornado wrecks a countryside, uprooting trees and tearing houses apart. The world that thus comes into being is barely a symbolic world. It is, rather, an undif-ferentiated world able to devour the very trace of the human. Its opening is an opening less to the Heideggerian-Derridean thinking of the Es-gibt, the generosity of language, a gift beyond economy, than to the horror of the Levinassean Il-y-a, the irremissibility of existence, the impossibility of

Impertinence 10�

death that comes with the most radical reduction: “Let us imagine all be- ings, things and persons, reverting to nothingness. . . . But what of this nothingness itself ? Something would happen, if only night and the silence of nothingness.”26 The fact of existence, the brute mere fact that there is there is, imposes itself even in the absence of beings. Levinas, who after all wanted to rehabilitate metaphysics, saw this terrifying finitude of an ungrounded existence incarnated in the work of Merleau-Ponty, and he faulted Merleau-Ponty and phenomenology on this account.27 In the postcolonial world (but perhaps, if Bhabha’s equation holds, in the postmodern world too) two irreconcilable politics come together: on the one hand, the politics of différance, of an untamable justice that gives force to the just law from the depths of nothingness and negativity; on the other hand, the politics of self-assertion, the absolute fundamentalism madly in love with the antagonism whose rejection is the essence of the foreclusion of the political. In Arguedas this second politics operates in the spirit of the reduction but only to exasperate the bracketing of the world beyond the limits of the critical intervention, pushing it into a region where criticism dissolves itself into its intimate opposite. After the most radical reduction takes place, the reader summoned to a reconstruction of the primacy of the world is left with nothing but “life, eternal life, the ceaseless world” (257). This annihilation of a valued world reveals the terrifying dimension of the aesthetic in its purity. It pushes the poet beyond the assertion of the worldliness of the world into a region that in its very radicalism refuses to be named. Arguedas assimilates this force-beyond-force to the totality of the existent and convokes the “frightening nights” to preside over a dia-lectic that is not one of finitude or infinitude but rather a destruction of the measure of the world in a realm “without end and without beginning” (257). This less-than-pagan, atheistic proposition brings about a terrifying act, and hence an act of terror: the literary act of a cornered animal that smashes the world of men with the blows learned in the school of a self-annihilating nothingness.

Notes

1 Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 173. Subsequent cita-tions are given parenthetically in the text.

2 Homi Bhabha, “In a Spirit of Calm Violence,” in After Colonialism: Imperial Histories and Postcolonial Displacements, ed. Gyan Prakash (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 331.

3 José María Arguedas, “Appeal to Some Intellectuals,” included in Katatay. Temblar in José

10� Horacio Legrás

María Arguedas. Obras completas. Tomo II (Lima: Editorial Horizonte, 1983), 252–57. All translations of quotes from the poem are my own; subsequent citations are given paren-thetically in the text.

4 Guillermo Rochabrún, ed., La Mesa redonda sobre “Todas las sangres” (Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2000). Subsequent citations are given parenthetically in the text.

5 The quote comes from the back cover blurb to the English edition of The Fox from Up Above and the Fox from Down Below (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000).

6 Antonio Cornejo Polar, Los universos narrativos de José María Arguedas (Buenos Aires: Losada, 1973), 82.

7 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “What Is Phenomenology,” in Phenomenology: The Philosophy of Husserl and Its Interpretation, ed. Joseph Kockelmans (New York: Anchor Books, 1967), 359.

8 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, trans. Alphonso Lingis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1968), 101–2.

9 See Homi Bhabha, “Of Mimicry and Man,” in The Location of Culture. 10 Tran-Duc-Thao offers an antiessentialist account of the phenomenological moment as a

negative deduction in his discussion of the reduction as “consciousness of impossibility.” See Phenomenology and Dialectical Materialism, trans. Daniel H. J. Herman and Donald V. Morano (Boston: D. Reidel, 1985), 4.

11 Slavoj Žižek, “Cartesian Subject versus Cartesian Theater,” in Žižek, Cogito and the Unconscious (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998).

12 Mladen Dolar, “Beyond Interpellation,” Qui Parle 2 (1993): 75–96. 13 Žižek, “Cartesian Subject versus Cartesian Theater,” 259. 14 Quoted in Slavoj Žižek, “Class Struggle or Postmodernism?” in Contingency, Hegemony,

Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left, ed. Judith Butler, Ernesto Laclau, and Slavoj Žižek (New York: Verso, 2000), 96.

15 Ibid., 127. 16 Giorgio Agamben, The Man without Content, trans. Georgia Albert (Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press, 1999), 68–77. 17 Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New

International, trans. Peggy Kamuf (London: Routledge, 1994). Subsequent citations are given parenthetically in the text.

18 Slavoj Žižek, For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor (London: Verso, 2002), 192. This concept of act bears an obvious parallelism to Badiou’s notion of event or truth-event, and sometimes Žižek uses both concepts interchangeably, as in The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Centre of Political Ontology (London: Verso, 1999), 164.

19 See Aijaz Ahmad, “Reconciling Derrida’s ‘Specters of Marx’ and Deconstructive Politics” (88–109) and Terry Eagleton, “Marxism without Marxism” (83–87), both in Ghostly Demarcations: A Symposium on Jacques Derrida’s Specter of Marx (London: Verso, 1999).

20 Negri himself does not discuss this idea of general intellect, which appears prominently in Empire (29), and implicitly in other writings. In the afterword to Ghostly Demarcations, Derrida partially rejects this reading of Negri.

21 “For without the phenomenon of other as other no respect would be possible. The phe-

Impertinence 10�

nomenon of respect supposes the respect of phenomenality. And ethics, phenome-nology.” Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 121. The expression “paradoxical phenomenality” appears in Specters, 6.

22 I have discussed the status of labor in Argueda’s Yawar Fiesta in “Yawar Fiesta: El retorno de la tragedia,” in José María Arguedas, hacia una poética migrante, ed. Sergio R. Franco, 61–79 (Pittsburgh: Instituto Internacional de Literatura Iberoamericana, 2005).

23 For Heidegger the inherited element in Western thinking was, of course, the thinking of Being. As he puts it in Enowning, “But in coming to grips with the first beginning, the heritage first becomes heritage; and those who belong to the future first become heirs. One is never an heir merely by the accident of being one who comes later.” Martin Hei-degger, Contributions to Philosophy (From Enowning), trans. Parvis Emad and Kennet Maly (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), 134.

24 Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century, vol. 2: The Wheels of Commerce, trans. Siân Reynolds (New York: Harper and Row, 1982), 25–26.

25 Agamben, The Man without Content. 26 Emmanuel Levinas, Existence and Existents, trans. Alphonso Lingis (The Hague: Martinus

Nijhoff, 1978), 57. 27 See Emmanuel Levinas’s “Intersubjectivity: Notes on Merleau-Ponty” and “Sensibility,”

in Ontology and Alterity in Merleau-Ponty, ed. Galen A. Johnson and Michael B. Smith (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1990).