Launching the Hawai'i Marine Science Studies Program€¦ · curiosity after he discovered...

Transcript of Launching the Hawai'i Marine Science Studies Program€¦ · curiosity after he discovered...

EDUCATIONAL PERSPECTIVES / 13

Launching the Hawai'i Marine Science Studies Program

E. Barbara Klemm

"Bloody eyeballs amt fried eggs are in I Iris orre I01J!" exclaimed t/1e/1iggcsl slr1de11/ in my class, a foolba/1 l'layer w/Jo was engrossed i11 Iris marirre science lab aclivity-1111 the day of 011c of t/ie /li,~ games, 110 less. He and /iis /lllrllrcr twre pccrmg 1/irouglr micmscopes al sa,rd snm/llcs from all arotwd tire U'Drld. He /,ad j11sl discowrcd that I/re snmc kinds of lirry marine organisms I/rat make 11/1 11

P"rl of //1e sands from Hawai'i, Fiji and ollrrr Pacific Island lieaclres arc also fcmml irr 11l'lldJ snml samples from Texns. I helped /rim ide11/ify these orgnnisms as types of Foramimfem am/ s11ggeslcd tlml l1e check refcmice books lo fi11d 0111 about t/1eir biology. I went 011 lo tire 11exl group of st11de11ts, a11/icipali11g /iis res1,011se as lie fo1111d co1111,·cticms wilh otean food drains, c/remiarl cyclir1g and satellite uceanc,gmp/Jy.

Al lire next stalrcm, /wo grrls lmd isolated lirig/1/•rcd, slri11y /Hlrlic/es from sand sa111/1le taken from II riwr bed. They Imel seen yelluw-grce11 crystnls in several Hawaiian bcac/J samls and recognized t/Jem lo be olivine, 011e of tire lmrdesl s11bst1111C,'S in volcanic material a11d 11111011g tire Inst of tire volcanic 11111/erinls lo erode away They had a/su se,·n colored frag111e11/s of beach glass, ,omc 1uw, 5/111rp and shiny arrd ot/1ers obviously older and dull with abrasion. T/Jcy 11ml rrevcr seen clear, bright-mt 1111r/icks like tlr,'Se before. "I wonder if ii 's a rul,y? • une aske,I me.

"Hmmm . .. , "I rtplied, roery /1it as curious as t/Jey twrc. "Haw could we find 011/?" Tlrc11 1 aclcled, "Wlrere could these particles luive come from?"

The girls 110retl uver a 1111/it'rback 110()1; 011 minerals, Iker, examined maps i11 a11 a/Ins, in their scarc/1 f()r clues. I ,r()/etl I/Jal /Irey were using ma/111i11g skills ,kvdoJ1cd earlier in tire semester and I/rat /Irey were asking good inquiry qrrestiorrs a/,ont geological processes. T/Jeir interest in identifying tire crystals drew them ir,/o marir1c topics on waler clrcmistry, minerals and mir1erol mi11i11g. Because t/1,'Y /111cl11 't ruled out glass, I reminded 111cm lo consider tire possibility tlrat those red s1iecks might /,e debris. T/Jcse str,dcnls were ninth graders al /he University Laboratory 5clrc~,I wlto lllr.'re lrdl'illg us lest newly crenled materials for /lie Hawai'i Marine Science Studies (HMSS) Jlrogram.

Background

HMSS is a product of the Curriculum Research and Development Group (CRDG) of the University of Hawai'i. HMSS materials consist of two companion student lab-texts with their companion teacher's guides, a series of four paperback readings with activities on the ecology, technology and politics of fishing, and an atlas of the Pacific coastal zone. In addition, there are a student record book containing drawing and tables useful in lab work and a set of overhead projector masters. The lab-texts, The Fluid Earth: Physical Science and Technology of the Marine Environment and The Living Ocean: Biology and Technology of the Marine Environment, have been tested by over 400 teachers. Some 50 scientists and engineers have contributed to and validated the scientific content. HMSS lab-texts are organized into units which are divided into topics containing one or more activities. HMSS materials can support a one- or two-year multi-disciplinary science and

technology course and are designed for students of all abilities in grades 9 through 12. HMSS is philosophically and pedagogically a sibling of the middle-school Foundational Approaches in Science Teaching (FAST) program, the first science program developed by CRDG. Ideally HMSS would follow FAST in a curricular sequence.

HMSS has been selected as an exemplary program by the National Science Teachers Association in its Search for Excellence in Science Education project. The program was rated on basic science content applied to real-world problems, on learning activities that have personal relevance to students as well as social relevance and on its treatment of career information. In 1994 HMSS was listed in Promising Practices in Mathematics and Science Education, published by the U.S. Department of Education. Analysis shows HMSS philosophy and content to be in alignment with current standards in science teaching, learning and assessment.

Content

The joy of teaching HMSS flows out the interest it creates in students who find Jakes, rivers and oceans places of excitement. Study of the ocean and other aquatic environments of the earth provides a powerful context for integrating biology, physics, chemistry, meteorology, geology, cartography, oceanography and ecology. The sand activity described earlier, for example, integrates mapping, mining, satellite oceanography, and biological, physicalchemical and earth science processes. HMSS ties classroom learning to contemporary local problems such as water pollution and debris deposition and to global concerns such as planetary warming' and rising sea level. New technologies that have modernized oceanography are an important part of HMSS studies. These include fisheries management, satellite oceanography, ocean-mapping and seafloor exploration. Activities are carefully crafted so that focus is on scientific concepts that will endure as our knowledge of the sea broadens and technologies change.

Environmental Universality

I became convinced of the universality of the content and pedagogy of the HMSS program when a fellow developer and I worked with a local Salem high school science teacher to take HMSS through its maiden voyage outside Hawai'i in a teacher institute in Massachusetts. We developers knew

14 / EDUCATIONAL PERSPEcrIVES

less than the institute teacher participants in terms of the specifics of the lake, river, wetland and ocean environments of New England. However, I was both relieved and profoundly impressed that the HMSS science content and instructional strategies were so fundamental that they worked and made sense as they were used to study the ecology of the cold, rocky tidepools off Marblehead and the stream and wetlands flanking the school.

Success with Students

Since then, HMSS teachers from around the country have shared with me their successes with students. One teacher returned from a Hawai'i institute to use HMSS with her students in Alaska. Her class made an audiotape of its HMSS field trip and sent it to me. I could hear whales in the background, but I was struck far more by the students' problem solving, particularly the ways they kept their samples from freezing as they collected them.

To give another example, I visited a marine science classroom in an urban Mainland U.S. high school. That morning about ten minutes before homeroom activities started, two students brought several friends who were not members of the class into the lab area. The teacher greeted them and let them wander about, pjfking up and talking about biological specimens and manipulating some equipment. These adolescents, on their own, were teaching each other science. The teacher told me the students were so "into" the program that there was a constant flow of friends into the room who wanted to be updated on what was happening in the class.

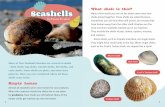

Most important of all are the HMSS successes with students who at the beginning of the year expressed dislike or difficulty with science. One of my students who had never done particularly well in school was riveted with curiosity after he discovered seashells in the stomach of the pelagic (open•ocean) fish he dissected. He became one of the most thorough lab observer-experimentalists I ever had.

The HMSS Design

Pedagogically, HMSS uses inquiry strategies described by some as "hands-on, minds-on" approaches to learning. HMSS students learn concepts and skills by experimenting with real or simulated marine phenomena and then thinking about and discussing their experiences. The inquiry methods used in HMSS are those used by scientists and engineers who study the ocean. For example, students construct and use wave tanks to study the properties of ocean waves and to simulate and test wave-beach interactions. HMSS wave tanks are very much like those used by early oceanographers except that the students use mostly recycled materials. The resulting HMSS wave-beach simulations are inexpensive

and remarkably like those used in sophisticated ocean engineering studies today.

HMSS is organized not just to convey information but to guide students in constructing their own knowledge and understanding. Students have latitude in what and how they explore topics, but HMSS investigations do not drift aimlessly. HMSS is structured so that students team and apply basic concepts from science and engineering in the context of specific problems or activities.

Students teaming about ocean waves, especially surfing waves and tsunamis, are surprised to find that they have also learned physics concepts. In HMSS "cook and eat" labs, students share multicultural knowledge about obtaining and preparing seafoods, learn practical information about human nutrition, and gain insight into basic biology, ecology and resource economics. They find mathematics essential to their studies as they plot shark attack data, figure out how to make scaled models of ships or whales, calibrate hydrometers, measure quantities of beach or riverside debris, or calculate pressure on a scuba regulator.

Whal Students Do

HMSS is a rigorous secondary science course and involves students in learning the major concepts and lab skills used by oceanographers. It is designed so that most of the concepts are developed by the students through activity, not through reading. HMSS hands-on activities cannot be skipped because they are an integral part of the learning process. If you were to give a cursory look at HMSS labtexts, you might think that they are hardback lab manuals, but they are neither lab manuals nor are they traditional texts. HMSS lab-texts provide enough information to launch class activities, leaving to student investigation and class interaction the building of foundational concepts. Throughout their concept building, students are prompted by questions about their observations, analyses and reflections.

For example, an art technique is used as the entree into the first biology activity in The Living Ocean, Topic 1, Fish Printing. Here students work together to make fish prints using the Japanese art form called gyotaku. They arrange the body, fins, mouth and other features of a fish to accentuate its uniqueness in an aesthetically pleasing fashion. Then they paint the fish's outer surface, place paper on top of the paint and gently pat or stroke it to make the print. The scientific purpose is to learn fish anatomy, practice observational skills and to gain proficiency in handling biological specimens. Before the prints are dried, even the most squeamish of the students are unconcernedly handling the fish specimens. Through art, students begin to acquire skills needed for study of all the organisms investigated in HMSS.

Most HMSS teachers can't take their students scuba diving, but many can go on field trips. HMSS provides numerous activities built around beach, stream and tidepool surveys and long-term investigations. Where teachers are not able to take students on field trips, they are encouraged to have students explore local water environments on their own and to get involved in caring for and wisely using those environments. Joining in a beach or stream cleanup gives students a vivid experience in associating uncaring human behavior with aesthetically offensive and environmentally damaging debris. By talking with classmates and people in other schools and the community who have worked on such projects, students become very aware that what is done locally has global consequences. The lasting message is that they as individuals can make a difference.

Developing HMSS

In developing HMSS, our first-draft units often began with a lot of written description and an idea for hands-on learning. After testing the draft work with students, we systematically removed words and sought other ways for students to get information such as graphics and questions that elicit prior knowledge and guide them to reason and problem solve. Again, often several times, we tested and redrafted. As a result, our activities about seafloor features are not learned through traditional written descriptions. Instead, they are learned by finding examples of seafloor features on contour maps, constructing models of these features from cardboard and labeling them using a glossary of terms. In our activities on pressure, students plunge an airfilled sensor into water and chart readings on a manometer. In our activities on invertebrates, students capture and maintain the specimens they observe, and in our activities on food chains and food pyramids, they carry manipulative simulations. Concepts and skills are learned through doing the same kinds of things that researchers do.

As we wrote HMSS, sometimes it seemed simpler just to write to convey information, that is, to tell the students what they should know. We learned this would cover more information, but the students would understand less. HMSS activities are structured to support students' active involvement in seeking and using scientific knowledge. Activities start with local concre te examples and lead to understanding of abstract large-scale global events and processes. Question sequences start by asking students for their observations and descriptions and then stimulate thinking about explanations and generalizations. Within each unit, HMSS topics are developmentally sequenced, starting from simpler ideas and building to more complex. Units or topics can be rearranged as needed.

As an alte rnative and complement to reading, HMSS graphics provide, use and help make sense of information.

EDUCATIONAL PERSPECTIVES / 15

For example, in the fish printing activity, students learn external fish anatomy by comparing the features of their gyotaku print with the labeled drawing of a typical fish found in their lab-text. Features that may be peculiar to their specimen can be found in illustrated glossaries. Systems diagrams, some schematic, some pictorial, some complete, some incomplete, appear throughout the text to enhance association with concepts. Maps, graphs, pictorial keys, illustrated flow charts of lab operations are all used to widen the scope of communication.

HMSS is designed to provide activities and opportunities to learn for all students in the regular program of the high school. Marine and other aquatic explorations are particularly appealing to visual and tactile learners. Throughout HMSS, activities provide opportunities for students to use their mathematical, spatial, manipulative, interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences (Gardner, 1987). Investigations at the end of each topic suggest ideas for related art, music and literature excursions.

Teachers' Preparation

In an HMSS teacher institute held in North Carolina, a group of teachers worked noisily at the back of the room. We had just visited a barrier island on a field trip and they had decided to test what might happen under hurricane conditions to the high-priced homes and three-story vacation condominiums we had seen under construction there. They had overturned a large table and lined it with a plastic drop cloth, making a wave tank. They had added sand, water, rocks and other items to simulate the beach, buildings and other shoreline features. Having made their model as realistic as possible and they tested it to see whether it could explain existing waves, currents and beach conditions. They were using it to predict the effects of a major storm.

Another group was working to simulate the impact of human foot and vehicle traffic on the sand dunes and their vegetative cover. Other groups had analyzed field data and were preparing maps _to show the distribution of coastal strand plants and animals as related to variables such as salt spray exposure. All groups were carrying out HMSS activities, even though the program contains no specific information about the North Carolina Barrier Islands. They were learning how to translate the universal content of HMSS into the particulars of their immediate environment.

As with other CRDG programs, HMSS is disseminated solely through teacher institutes. During HMSS institutes, teachers construct maps, models, wave tanks-, aquaria and a number of other teaching aids that they will be using in their classrooms. They learn what organisms to look for in supermarkets or fish markets to use in teaching marine biology, and they trade seashells, sponges, coral and other specimens they have been asked to bring to the institute for

16 / EDUCATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

exchange. At the end of a ten-day teacher institute, they go back to their home schools with bulging notebooks and suitcases heavy with sand shells, and books. Soon their own students will be adding to class collections, bringing in more specimens and books and pictures about sailing, diving and surfing.

Climate, economic constraints, insurance concerns, administrative problems and worry over impact on the environment severely limit the number of local field-based studies most teachers are able to undertake with their marine students. Even in Hawai'i where the climate favors outdoor work, teachers usually take no more than one or two field trips per year. The goal in instructing HMSS marine science teachers is to prepare them to bring the lakes, rivers, oceans and beaches into their classroom so that their students can investigate phenomena associated with water environments all year long.

Why Marine Science and HMSS?

In tight budgetary times, it is reasonable to ask why marine science, and HMSS specifically, should be taught at all. There are several educational reasons:

•

•

•

•

In Hawai'i and elsewhere !he high school graduation requirement has been raised to three years of science. Programs that are standards-based and intellectually accessible to all students are needed. HMSS is such a program (Young, 1996).

HMSS is flexible in its contribution to the total science curriculum of the school. In some schools it is used as a ninth grade alternative to physical science or as an elective that may be taken at any time. In others, it is used as a capstone course after students have completed work in biology and the physical sciences. HMSS is also used as a two-year course of study in which The Living Ocean and The Auid Earth are taught as separate studies.

HMSS offers an appealing option for science-phobic students. It opens the door of science to many students who have not been able to enter before by presenting science as an experience with real objects, environments and processes from which students create verbal descriptions.

For students intending to pursue science as a career, HMSS reinforces and enriches

their understanding of basic chemistry, physics and biology. It introduces them to engineering and may be their only encounter with the earth sciences.

Beyond its appeal as an interesting and Jearnable course, HMSS deals with fascinating places that students find relevant to their lives. We live on earth, the planet that is unique in the solar system because of its vast oceans and lakes and because it supports life, yet our curricula are almost totally land-based. If our citizens are to be literate about the world around them, they need some fundamental understanding of our natural world and how it works. All life on our planet is interconnected; water makes life possible and the planet habitable. Science study, in particular environmental study, is needed more than ever in our schools today so that students learn that they are part of nature; that the earth, the waters, the atmosphere and all living things are indeed connected and interactive; that what we do matters and that what we teach and learn in school matters.

Conclusion

In keeping with the new national standards, the science curriculum of the schools should include a solid foundation in the environmental sciences. HMSS is such a program. It is both popular and successful with students. Be warned though, HMSS changes lives. Students tell me that they'll never be able to go down to the beach or a river again without looking for treasures in the sand. Once they've studied waves, some claim they see other wave patterns everywhere around them. All develop a better understanding of the world and their place in it. The ideas released through the HMSS experience are powerful and empowering.

References

Gardner, H. 1987. Fmmcs of Mind: The 11,rory of Multiple /11lellige11ccs, New York: &sic Books

Young, DB. 1996. Alignment of Foundalional Approaches in Science Teaching (FAST) and Hawai•i Marine Science StudiL'S (HMSS) wilh lhl! Nalional Standards for Science Education Grade; 9-12. Honolulu, HI: Curriculum RL'Scarch & Dcvclopmcnl Group.

E. Barbara Klemm was a member of the original HMSS development staff, served as Co-director of the HMSS project during writing of its third edition, was first author of that edition and was an author of FAST Ecology and Relational Study materials. She is now an associate professor in the Department of Teacher Education and Curriculum Studies, College of Education, University of Hawai'i at Manoa.