L CULTURE AND MEDIEVAL EUROPEAN LITERATURE* Jullr Scorr · L I t: t a ic ls [-KS 0-0e e) ls. ns he...

Transcript of L CULTURE AND MEDIEVAL EUROPEAN LITERATURE* Jullr Scorr · L I t: t a ic ls [-KS 0-0e e) ls. ns he...

!

L

I

t

:

t

a

ic

ls[-KS

0-

0e

e)

ls.

ns

he

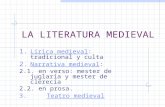

ARABIC CULTURE AND MEDIEVAL EUROPEAN LITERATURE*

Jullr Scorr Muslt'tI

UNlvrRsrrv or Oxrono

The book under review takes up the question of Arabic influence on medieval Europeanliterature from the perspective of the attitudes which inform critical discussions of the topic. Theauthor associates negative responses to suggestions of Arabic inffuence with a "myth of Western-

ness" inspired by European colonial attitudes toward the East, and presents considerable evidencefor the cultural interaction of Andalusian and Sicilian Arabic culture wilh that of medieval Europe.While much of the material is familiar, the arguments for such interaction are convincing, and thereadings offered of specific texts are thought-provoking; and though the book is somewhat marredby its polemic tone, it raises significant issues with respect to the aims and methods of literaryhistoriography and comparative literary studies.

THr Anesrc LTTERATURES oF MEDIEvAL SpetN andSicily do not occupy an important position in Arabicstudies; the domain of a few specialists, they are typi-cally viewed as peripheral to the tradition as a whole.Still less, being Arabic, are they considered relevant toEuropean literary history, despite the close contactsbetween medieval Arabic and European culture in theMiddle Ages. Menocal seeks to reawaken our aware-ness of the Arabic contribution to medieval Europeanliterature, which without its Arabic component is, she

asserts, sadly truncated; her discussion raises issues

which go beyond the boundaries of Arabic, Hispanic ormedieval studies and which warrant serious attention.

Menocal argues that the resistance of many medieval-ists and most Hispanists to so-called "Arabic theories"of the origins of, for example, troubadour poetry stemsless from scholarly objections than from the fact "thatEuropean scholarship has an a priori view of, and set

of assumptions about, its medieval past that is far fromconducive to viewing its Semitic components as forma-tive and central" (p. xiii). (The designation of suchcomponents as "Semitic" is unfortunate; for while itincludes the Hebrew element, it obscures the fact thatmany, if not most, of the bearers of Arabic culture inAndalusia and Sicily were of non-Arab origin.) Thecentral question she wishes to raise is thus not one ofinfluence but of method, of "why discussions of suchpossibilities had such a different cast from others thatconcerned the medieval period and its cultural milieu"

t A review article of: The Arabic Role in Medieval LiteraryTheory: A Forgotten Heritoge. By Mnnrr Rose MrNocrl.Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: UNrvrnsrry or PsNNsyr-vrNte Pness, 1987. Pp. xvii + 178. $27.95,t26.55.

li r,r:u rl

(p. xii); and in her first chapter she sets out to examinethe assumptions that shape our view, as Westerners, ofthe medieval past.

Western hostility toward suggestions of Arabic influ-ence on medieval European literature reflects whatMenocal terms the "myth of Westernness"-defined as"the image or construct we have . . . of ourselves andour culture, an entity we have dubbed 'Western'," theproduct of a cultural history viewed as both uniqueand normative and assumed to be "in distinctive, neces-sary, and fundamental opposition to non-Western cul-ture and cultural history" (pp. l-2)-which constitutesan informing paradigm of modern historiography, liter-ary and otherwise. Following the lead of Edward Said'sOrientalism, she identifies the root of this myth as

political: the need to assert Western superiority overthe East, the Other, leading to a rejection of the possi-bility of fruitful contact with that Other, defined retro-spectively as inferior and thus deserv-ing of subjugation.She traces the myth's origins to the Renaissance re-discovery of its classical antecedents (no longer avail-able only through Arabic) and their elevation to acentral position in the cultural tradition, and its con-comitant rejection of much of its medieval past, viewedas the darkest of Dark Ages. But the crucial period ofits formation was the nineteenth century, "this momentof the high-pitched awareness of the particularity andsuperiority of Europe that came with the imperial andcolonial experience and the post-Romantic experiencewith the Orient" (p. 6), a period which, not by coin-cidence, saw the development of both orientalism andphilology as well as the beginnings of modern medievalstudies and the rehabilitation of Europe's medievalpast.

343

344 lournal of the American

But the dominant paradigm of medieval literary his-tory was, I suggest, developed in the first half of thiscentury, between the two world wars, largely as a re-sponse to European political and cultural fragmenta-tion. Two seminal works of this period attempted toinstill a sense of European cultural unity: Erich Auer-bach's Mimesis (19a6), written during his exile in Istan-bul (and described by Edward Said as "an act ofcultural, even civilizational, survival of the highest im-portance" [Said 1984, 6]), which sought to define theessential styles of Western literature, and Ernst RobertCurtius' Europai'sche Literatur und lateinisches Mit-telalter (1948\.

Curtius'view of the European Middle Ages may besaid to represent the canonical narrative of the period,a.nd is both paradigmatic and exclusive. There is no

lllace in it for non-European elements, nor does Cur-tius'"comparative approach" envision for such ele-

ments a formative role, as is seen by his handling ofpotential areas of comparison. Dante's meeting, in theCommedia, with the bella scuola of classical auctoresbecomes for Curtius an emblem both of the authorita-tive status of antiquity and of the Latin Middle Agesas 'the crumbling Roman road from the antique tothe modern world" (Curtius 1963, I 9); the long chapter*n Dante makes no mention of Arabic contacts (AsinPalacios' La escatologia musulmana en la DivinaComedia, first published in 1919, is ignored). Latinityis the source of all European culture: scholasticism's

Ereatest debt is to Boethius, that ofgeneral knowledgeto Isidore of Seville, that of literature to Fortunatus,aJl luminaries of the 6th century.

The Arabs, historically important because their "in-cursions" herald the end of antiquity, are culturallynegligible because culturally unassimilable, in contrastto the Germanic peoples who helped to perpetuate]loman Latin culture. The true homeland of this cultureis Romania, unified by the Romance languages; themultilingualism of its writers does not include Arabic,and indeed, in this Romania the Arabs are largelyrnvisible. Their transmission of Greek learning is briefly:;oted (in the context of the scholastics'purification of.qristotelianism from Averroistic tendencies); but, in;general, philosophy's debt to the Arabs goes unmen-lioned, although a Hellenized Jewish connection is

admitted. The seven-hundred year Arab presence inSpain is dealt with by virtually ignoring that regionuntil the sixteenth century; an excursus on "Spain'sCultural Belatedness" resumes the views of ClaudioSdnchez-Albornoz ("Espafra y Francia en la edadr.**dia," rRevrslc de Occidente, 1923); the conjecture ofr',,irli*r beginuings based on the presence of Romance,:harjes in Arabic and Hetrrev; muu'ashshaftdl is else-

Oriental Society I I 1.2 (1991)

where dismissed in a footnote. In a short section entitled"West and East" the influence of Arabic poetry on thepoets of the srg/o de oro ts briefly admitted: SpanishMannerism is termed a mingling of "the medieval Latinand the Eastern ornamental styles" (ibid., 343) to itsdetriment, precisely because of its resemblance to East-ern literature.

Curtius'approach reflects what Claudio Guill6n calls"the atmosphere (redolent with mythomania) in whichthe idea of national literature thrives" (Guill6n 1971,

188). For Guill6n, as for Menocal, the study of eitherSpanish or European literature is meaningless withoutconsideration of its oriental components: "No defini-tion of European civilization, and especially, of Euro-pean literature, which excludes Spain or fails to takeinto account the impact of Islamic and Hebrew historyon Europe is at all viable" (ibid., 474, and see pp. 472-75). Yet can this view of medieval Europe, one-sidedthough it is, be attributed to negative political motivesand specifically to a colonial mentality which views the

Arabs as inferior? Certainly other, more complexfactors influenced not only Curtius'approach, but themore extreme view of many Hispanists of Spanishliterary history, which takes its normative form in thesame period. Thomas Glick, discussing what he terms"the present polemic" of Spanish historiography (which,though its roots are in the interwar years, becameclearly articulated in Am6rico Castro's Espafta en su

historia [948] and S6nchez-Albornoz' response, Es'pafia: Una enigma hist6rico [956]), has shown thatthe focus of this polemic, not on "the definition ofmechanisms and processes governing cultural contactand cultural diffusion but . . . [on] the issue of modalpersonality ('national character')" (Glick 1979, 7-10),may be traced to complex social-psychological motiveswhich have their origins deep in the Spanish past:

"Transposed into the historiographical field, subcon-scious fears became transferred into bias that underlieshistorical interpretation and contributes to misinterpre-tation"(ibid., 3). In other words, a political interpreta-tion of such difficulties in historiography oversimplifieswhat is, at base, a far more complex probler:r.

On the other hand, that such paradigms of nationalor literary identity based on myths of exclusivity and

otherness are operative in contemporary criticism can"

not be denied; nor can the fact that, as Menocal justlyobserves, they are reinforced rather than countered bythe sibling disciplines of orientalism and philology.Orientalists, she states, "have been no more exemptfrom the prejudices of cultural ideology than the med-

ievalist community as a whole" (p. 18, n. 5), and theirstudies reflect equally sweeping asslrmptiorls of the su-

periority and normaiive status of Weslrrn, and the

l:'1:

;l#{*X"iiE F:l.i*i$ri

Mrtsrut: Arabic Culture and Medieval European Llterature 345

intractible otherness of non-Western, literatures. Thecontrast between the potential of orientalism to com-bat the "myth of Westernness" and its role in perpetuat-ing the West's self-image is ably brought out in two verydifferent studies of the discipline: Raymond Schwab'sLa Renaissance orientale (1950; not cited by Menocal),which examines the impact of the "discovery of theEast" on European intellectual life from I680 to 1880,and Said's Orientalism (1978), which portrays the for-mation of the image of the East as Other, aided andabetted by orientalism's appropriation of its culturesas material for study.

Of the two, Schwab is the more successful in placingorientalism in its broad intellectual, and not merelypolitical, context; sympathetic in his approach, he is

also aware of the tension between the potential of this"second Renaissance" for creating a new "global hu-manism," and the development of orientalism itselfinto an increasingly specialized academic discipline(Schwab 1984,4,8 and see pp. I-8). His task was thus(as Said puts it) "to study the progress by which theWest's image of the Oriental passes from primitive toactual, that is, from disruptive iblouissentent incriduleto viniration condescendanle" (Said 1984, 252). Saidcriticizes Schwab for his apparent lack of interest in"the economic, social and political forces at work dur-ing the periods he studies. . . . Never does he coherentlyput forward a thesis about Orientalism as a science,attitude, or institution for the European military, politi-cal, and economic control of Eastern colonies" (1984,263). lt is this dimension of orientalism which Saidhimself seeks to demonstrate by examining "the politi-cal questions raised by Orientalism," among them:

What sorts of intellectual, aesthetic, scholarly and cul-tural energies went into rhe making of an imperialisttradition like the orientalist one? How did philology,

lexicography, history, biology, political and economictheory, novel-writing, and lyric poetry come to the

service of Orientalism's broadly imperialist view of the

world?.. . In fine, how can we treat the cultural, his-torical phenomenon of Orientalism as a kind of u.illedhuman x'ork. . . in all its historical complexity, detail,and worth wilhout at the same time losing sight of the

alliance between cultural work, political tendencies,

the state, and the specific realities of domination?"(1978, l5; author's emphases).

Said, as Menocal herself observes (pp. 2l-22, n. l2),ignores Spanish orientalism (thus further contributingto the marginalization of Hispano-Arabic studies), pre-ferring to concentrate on the more obvious excesses ofthe English, the French and the Americans-excesses

which are more easily explainable in terms of colonialand post-colonial political motives. For Said (andIargely for Menocal) political considerations are centralto Orientalism, defined as "a style of thought basedupon an ontological and epistemological distinctionmade between 'the Orient'and (most of the time) 'theOccident"'(1978, 2). The East is thus defined as amirror image of the West-an image all too familiar inthe writings of, for example, G. E. von Grunebaum,whose approach to trslam Marshall Hodgson describedas based on a "Westernistic commitment or outlook"which ensures that "the formative assumptions ofIslamdom . . . are derived at least in part negatively, byway of contrast (what Islam lacks), from certain con-trary formative assumptions he ascribes (in the Western-istic manner) at once to the West and to Modernity. . . .

The formative assumptions he sees in the West, on thecontrary, turn out to be central to what is most dis-tinctly human" (Hodgson 1974,2:362, n. 6).

But while ideology is clearly important in the forma-tion of such an image (just as it dictates the search, byvon Grunebaum and others, for an "essential Islam"which in all its lineaments would conform to thatimage), it may be argued that it most often representsan outlook which generates individual and collectivemisreadings, rather than a program, a conspiratorialeffort to suppress the Other. To treat all instances ofwhat is often openly hostile incomprehension as "atbottom" political (Said 1978, 299) fails to account forother factors which must also be acknowledged if weare to revise our attitudes toward historiography, liter-ary and otherwise.

One such factor is undoubtedly academic vested in-terest and adherence to reductive methods of literarystudy, exemplified by the central position of philol-ogy-itself (as Schwab shows) a product of oriental-ism-among these methods. For Curtius, philologywas the key to unlocking the essential unity of Euro-pean literature; orientalists see it as the means of un-covering the secrets of Eastern texts. But as WaltherBust observed, "No text was ever wlitten to be readand interpreted by philologists"(quoted by Jauss I982,I9); the philological method leads away from the con-sideration of texts as literature. Jaroslav Stetkevychonce asked if Arabists are "basically. , . not even in-terested in literature, because we are philologists, his-torians, or disguised social scientists: in one wordbecause we are 'orientalists'?" and was led, likeMenocal, to inquire, "Why should our methods, ourcritical conceptual apparatus, the very repertory ofquestions we seem to be asking of literature be so farapart from what others do about and ask ofliterature?"(Stetkevych 1969, 148-49). Elsewhere he traced the

346

separation of orientalist philology from culture andliterature to its pursuit of the "perfect text," aboutwhich, once achieved, the philologist'would more oftenthan not decide either that it was not worth reading orthat it ought to be used elsewhere-not in literature"(1980, I I l). Philology's more recent heirs-structural-ism, which often assumes that knowledge of the syn-chronic state of a language is sufficient for analyzing itstexts, and the New Criticism, with its ideal of the textas self-sufficient literary artifact-perpetuate this sep-aration of text from culture by removing it from itsconditions of production and reception. Yet is it suffi-cient to argue (as Menocal appears to do) that suchmethods serve primarily to mask the input of ideologyby positing objectivity while continuing to read non-Western texts in ways which reinforce the "myth ofWesternness"? ls it not also the entrapment of philologyin its own methodological limitations, its unwillingnessto move beyond the text, which contributes to whatMenocal terms the "double standard" of scholarshipwhich plagues the study of medieval Eastern literatures?

That this double standard exists is beyond question.One form in which it manifests itself is the view (alsoan offshoot of philology), held by Europeanists andorientalists alike, that the methods employed in thestudy of Western literature are of dubious or negativevalidity for Eastern; another is the modification of theentire concept of "literature" as applied to the East,where "a distinction is made between poetry and otherintellectual life that is difficult to reconcile with theunity of such traditions in virtually every other sphereof literary study" (p. 17 , n. 4), leading to the divorce ofliterature from other areas of life. This distinctionmakes it possible to accommodate the historical fact ofthe transmission of scientific and philosophical learning(the emphasis being customarily placed on texts ratherthan ideas) by the Arabs to Europe, while assumingthat such areas of culture have nothing to do withliterature.

A problem that Menocal does not explicitly addressis that in practice literature is defined, especially byorientalists, much as the individual critic wishes. The"molecular theory" of Arabic poetry, for example, de-rived originally from philology (cf. Ahlwardt's dictumthat the "Arab mind" is unable to perceive anythingbut "singularities"[cited by Stetkevych 1980, II2-13])was later linked (notably by von Grunebaum) to an"atomistic" worid-view characteristic of "essential"Islam, and invoked in the analysis of all medievallslamic poetry. On the other hand, when scholars likeOibb or von Grunebaum deplore the'literarization" of11.{uslim historiography (when that discipline was takenr-rver by court secretaries), they divorce *literature"

Journal of the American Oriental Soeiety lll.2 (199/)

(now defined as belles-lettres) from the ideally "objec-tive" discipline of history (a distinction currently chal-lenged by medievalists). To define literature either as

the expression of national character or as consistingonly of belles-lettres (a concept alien to medieval liter-ary systems) yields equally reductive models; but theproblem here is not merely one of ideological mythifi-cation but of methodological adequacy.

The double standard, as Menocal points out, alsoapplies in matters ofjustification and documentation, a

problem of particular importance for comparative stud-ies. For while studies of Celtic or Germanic (as ofLatin) contributions to European literature are admit-ted because their inclusion "does not challenge theboundaries of the image of the medieval period" (p. 8),and require little justification, comparisons of Hispano-Arabic with troubadour poetry (for example) mustbe extensively rationalized and rigidly supported bytextual evidence, though in all likelihood such contactsas occurred between the two were non- or extra-textual,intercultural rather than narrowly literary, and literarydocuments are inadequate either to prove or to disprovetheir existence.

Thus Menocal concludes that traditional literary his-toriography, based on the canonical paradigm of the"Westernness" of European literature and the Other-ness of non-European, is unable to bring about themuch-needed revision of medieval literary history be-cause it reads that history in terms of its "victors." Shedoes not propose that we reject this narrative in toto(thus scrapping its many valuable achievements), butrather that we should discard "that part.. . that haseliminated the possibility of seeing in the Andalusianworld the impetus for change and . . . that cannot imag-ine that a cultural force now seemingly alien to ourown was once a part of its foundation" (p. l 5), in orderto create an alternative narrative which "does not shyaway from the concept ofa mixed ancestry for westernEurope. . . . [and] enriches rather than impoverishesthe recounting of the story we already work with"(p.16).

Such revisions have been attempted before, as Me-nocal's bibliography makes clear; and much of thematerial which she presents in the following chapters isfamiliar. Norman Daniel's studies on Islam and theWest, Alice Lasater's Spain to England (1974), PierreGallais' Gtnise du roman occidental (1914), DorotheeMetlitzki's The Mauer of Araby in Medieval England( I 977), and Vernet's la cultura hispanodrabe en Orientey Accidente (1978) are only a few of the studies which,in the past two decades, have attempted to describe thecontacts betwein Arabic and European i."xlture as pro-ductive rather. than confrontational. The ifstatement

4nC#L'

Mrtslul: Arabic Cu!,ure *nd lt{edieval European Literature 34'.t

of such material in the context of Menocal's criticismof traditional paradigms of literary and cultural historyis, however, not unwarranted, especially since the viewof medieval cultural exchange presented by Menocal inher second chapter ("Rethinking the Background") is

somewhat less partial than that which characterizes thestudies cited above.

Menocal focuses on four representative figures-William IX of Acquitaine, Peter the Venerable, Eleanorof Acquitaine and Frederick lI of Sicily-and on theintellectual milieu of twelfth-century Paris. The pano-rama of cultural exchange-the presence of Arabic-speaking singers and musicians at European courts, themovement of scholars, translators, merchants, envoys,and poets between Europe, Spain, Sicily, and the East,the contacts furnished by pilgrimages, military engage-ments, marriage, and commerce, the activities of trans-lators, the multi-lingualism which characterizes theperiod-is reconstructed in painstaking detail. Refutingthe common equation of Arabic culture with Islam andits resultant opposition to Christianity, assumed to bethe central and formative determinant of Europeanculture, Menocal reminds us that Arabic was the pres-tige language of a high culture, and that those wholearned it were more interested in the refinements ofthat culture than in doctrinal matters. (Exceptions suchas Peter the Venerable-the first translator of theKoran-who warned against the seductiveness of Ara-bic culture precisely because he believed the Latinswere ignorant of its association with Islam, or the ParisAristotelians who opposed Averroistic "heresies," provethe rule.) Political and religious antagonisms, far fromproving a barrier to cultural contact, often enhanced it:the fall of Toledo in 1085, for example, accelerated thediffusion of Arabic culture throughout Europe.

Stressing its polymorphic nature and the variety ofways in which that culture, "Arabic in expression andAndalusian and Sicilian in immediate point of origin"(p. 35), was disseminated, Menocal notes *the essentialfallacy in assuming that what is Arabic in medieva!Europe is necessarily Islamic or that what was ori-ginally something else (Greek or Persian, say) was notreceived as Andalusian"(p. 37).This has clear implica-tions for comparative studies, and particularly forsource studies; and here the academic double standardmanifests itself once more. For while it is of genuineinterest to the specialist that specific elements in An-dalusian culture may stem from more ancient origins,the tracing of which provides information on patternsof cultural dissemination, the appeal to ultimate sourcesoften provides a convenient rationale for bypassing thegroups responsible for transmitting materials from theirremote origins to their European recipients.

Such is the case in Donald Lach's lsra in the Makingof Europe (1977), where the distinction between "Asia"and "Europe" and the focus on origins make it possible

to minimize the role of Arabic culture as an agency fortransmission. Lach (like many others) limits himself totextual evidence: 'Because of the obvious complicationsinvolved in studying the migration of literary themes. . . the only certain ground to stand on is that providedby the actual translations of Indian works into Westernlanguages" (Lach 1977, l:27). This begs the questionof intermediate versions, since none of these "actualtranslations" were made directly from Indian sources,

and places severe limitations on his study; thus, whilepassing mention is made, with reference to the migra-tion of Indian tales to Europe, of "intermediary Arabic,Syrian [sic], and Persian translation" (2: l0l), little at-tention is given to the actual contribution ofsuch trans-lations. The discussion of Dante's "Oriental sources"focuses on their Indian and Far Eastern origins (whileDante's "image of Asia" is said to be "founded uponthe learned tradition deriving from Pliny, Solinus, andIsidore" [:75]); there is no mention of the mosques ofDis or of the Libro della scala, and Lach is puzzled atDante's placing the terrestrial paradise in Ceylon (oneof its traditional locations in Arabic sources). Boccaccioand Chaucer were influenced (presumably without thehelp of Petrus Alfonsis) by Indian narratives (KEliddsa,

the Ramaya4a) and Buddhist parables (the'Pardoner'sTale" resembles a parable from the Vedabba Jataka;Marco Polo is suggested as the source of imagery in the"Squire's Tale"); and the ultimate source of the Sec-

retum Secretorum is identified as Indian. While all thisis of undoubted interest, it in no way accounts for theform in which such materials actually reached Europe;India may well be the archetypal source of story, butthe discussion of "the migration of tales to the West,"based on the evidence of texts alone, is misleading, as itignores both the importance of oral transmission andthe fact that transformations and distortions are morelikely in such transmission than in written translations.Moreover, Lach assumes that religious hostility be-tween Christians and Muslims constituted an insur-mountable barrier to cultural exchange, and concludesthat th€ most important accomplishment of the Cru-sades was "bringing home to all of Europe the funda-mental conflict and radical differences which existedbetween East and West"(2:109).

As Menocal rightly observes, the notion that literarycontacts are primarily textual "is dependent on ananachronistic view of what constituted literature andassumes an arbitrary division between different seg-

ments of the intellectual and artistic communities"(p.58). She is not the first to argue that studies of

J

348 Jaurnal of the American

cultural and literary exchange cannot be limited totextual contacts (nor confined to "literature" in the

narrow sense of belles-lettres); in an age when theprimary means of the transfer of knowledge was oral,"it requires no more than one instance of oral transla-tion . . . to effect the transmission of a bit of literaturefrom one language and culture to another. It is an

anachronism to assume that developments in literaturewere solely a scholarly enterprise" (p. 60). We cannotimagine that Christians closed their ears when Arabssang, told stories, or discussed ethics, philosophy, orlove, or invoked the language barrier in an age when

"foreign" languages were neither manifestations of the

Other nor (in consequence) specialized academic disci-plines, but tools ofeveryday social, cultural and com-mercial interchange.

Menocal also challenges the view "that influence

means or implies servile copying, [or] that its effects

result in a text that is indistinguishable from the one

that has inffuenced it" (pp. 60-61). This position, withits roots in nineteenth-century philology, stresses rap-ports de fait, confuses *influences and textual similari-ties" and fails to distinguish between such similarities(which may be coincidental) and what Guilldn calls'genetic incitations," that is, the impact of a variety offactors (literary and otherwise) on a writer prior to the

composition of a specific text (Guill6n 1971, 33-34). AsRoger Boase has noted, "it is not the products thatinfluence, but creators that absorb"(cited by Menocal1981, 49); literary dynamics operate in complex andessentially unquantifiable ways. It is to some aspects ofthese dynamics that Menocal turns in her last fourchapters, which focus less on questions ofgenetics thanon broader issues ofcultural and literary exchange.

Chapter 3 deals with the "oldest issue," that ofcourtly love and the poetry of the troubadours. Thecentrality of that poetry to the development of Euro-pean lyric poetry made it the object of intense study byearly Romance philolory, and raised questions conc€rn-ing the origins of vernacular lyric that still dominatemuch contemporary scholarship. Curtius' discussionof the beginnings of vernacular literatures was limitedto French narrative poetry, presumably because a Latinconnection could be clearly demonstrated; for manyother scholars, however, courtly lyric has come to exem-plify what is distinctively and uniquely "Western," andis bound up with images of European identity.

Theories on the origins of courtly love are myriad;but, Menocal argues, despite the wide range of sources

suggested (Marianism, Catharism, mysticism, folklore,Ovidian imitation, and so on), the possibility of non-Enropean, non-Christian sources is generally rejected..4s the rise of this area of study came during the periodwhen Europe was *shaping its views of the Arabs as

Oriental Society lll.2 (1991)

colonial subjects . . . the Arabist theory [oforigins] notonly ceased to be one of those theories advocated,denied, or discussed; it became virtually taboo"; onlythose theories which did not violate the "fundamentalprinciple of Europeanness" were further developed(p. 82). This, it should be noted, is not strictly true; forwhile the *Arabic theory" is often ignored in the class-

room, the vast literature on the subject testifies to the

continuing vigor of the discussion; and it is of some

interest to observe curious role reversals, in whichan orientalist like Samuel Stern (the 'discoverer" ofthe romance kharjas) opposes the notion of Arabicinfluence, while the admittedly chauvinistic S6nchez-Albornoz vigorously supports it.

Faced with the obvious parallels between Europeanand Arabic love poetry and theory, some scholars arguethat these similarities represent the parallel develop-ment (often from common, but ancient, sources) underparallel circumstanc-es of traditions otherwise unrelated.Von Grunebaum's view is representative: "The interac-tion between East and West in the Middle Ages willnever be correctly diagnosed or correctly assessed andappraised unless their fundamental cultural unity is

realized and taken into consideration. It is that essentialkinship of East and West that will account both forEurope's receptiveness to Arabic thought and to the(more or less) independent growth in the Occident ofideas and attitudes that on first sight appear too closelyakin to their oriental counterparts not to be attributedto mere borrowing"(1952,238). This is a curiously, butcharacteristically, ftzzy statement-where does kin-ship end and independence begin?-and to this viewMenocal justly takes exception. "It would be morereasonable," she argues, "to assume something otherthan parallel development when one observes the ap-pearance of quite similar and distinctive features in twoschools of lyric poetry, one arising in the wake of theother, in two regions near each other and with no lackof communication, indeed with all sorts of traffic, be-tween them" (p. 85). And indeed, one would expect notonly similarities but differences, as any'borrowing" (aterm which I suggest would be better subsumed underthe medieval concept of inventio) would reflect adapta-tions both to individual temperaments (William IX'sparody ofcourtly topics also assumes an awareness ofsuch topics) and to specific aspects of the cultures inquestion (the virtual absence of adulterous love as a

topic of Muslim poetry points primarily to differencesbetween Muslim and Christian social structures ratherthan to doctrinal conflicts).

In chapter 4, on the muwashshaftdt, Menocal criti-cizes the traditional limitation of comparative studiesby criteria of historical filiation: texts are comparedwhich are assumed to have some genetic relationship,

rr&,i$E,er.

Mrrsrur: Arabic Culiure and Medieval European Literature 349

further established by means of the comparison, a her-meneutic circle which discourages synchronic studieswhich would illuminate the salient formal features ofthe texts in question (p. 92). While genetic issues cannever be wholly ignored, Menocal suggests that thedemonstration of filiation cannot be an a priori candi-tion for comparative studies; and, by way of demon-strating "that our revisionist view of medieval Europeancultural and literary affairs can be of value for some-thing more than establishing which came first or whereany debt is owed" (p. 93), she offers a "metapoeticreading" of the muwashshofia in terms of its formalalterities.

Criticizing both Arabists and Romanists who treatthe muwashshaha's parts as separable and focus oneither the Arabic portion or the Romance kharja,Menocal advances the view that the form's organicityis based on the opposition between a courtly, malespeaker in the Arabic portion and a non-courtly, femalespeaker in the kharja (an opposition illuminated byGlick's description of the typical Andalusian marriagepattern as between'men who were bilingual Romanceand Arab speakers, women who were monolingualRomance speakers" [Glick, 1979, 177D. This formalstrategy has parallels in later Romance forms (the Pro-vencal canso, the pastourelle, the dialogic poems ofCountess Beatriz di Dia) which also employ contrastingregisters of diction, specifically courtly versus colloquial(it is also parodied in William IX's "Farai un vers, posmi somelh"). Menocal's analysis demonstrates the valueof a synchronic approach not only in clarifying affini-ties between Hispano-Arabic and European lyric butin investigating questions ofliterary universals; but theapproach also has its limitations, ignoring historicalprecedents (e.g., in the lyrics of Ab0 Nuwds) for theconclusion of a poem with a quotation in anotherregister which would also be illuminating. Moreover,the emphasis on thematics fails to account for the waysin which the muwashshofra's final sr'rnr prepares for thetransition to the female, Romance voice, and the ques-tion of the form's musical component, particularly as itrelates to Provencal lyrics, remains unexplored.

One might also inquire whether the reluctance ofmany scholars to deal with the muwashshalta in liter-ary terms on the one hand, and on the other to considerthe Romance kharja a.s an early stage of Romancelyric, stems not only from an assumption of the mutualexclusivity of the Arabic and European traditions, butfrom the popular nature of the poems themselves (aproblem even more marked in the case of the zajal)?The notion that literary influence is mediated solely bytexts reflects an elitist view of literature which posits anunbridgeable gulf between the literary-textual aod thepopular-oral levels of culture-a distinction which, as

Menocal notes in passing, is untenable. The interactionbetween these cultural levels, or registers, seen in themuwashshaha is peculiarly evocative of the polymor-phic culture of Andalusia, and explains the incompre-hension with which eastern Arab critics received it; buttheir prejudices should not be ours.

In chapter 5 ("The Anxieties of Influence") Menocalturns to Dante to propose a reading ol the Commedioas, in part at least, a reaction to what the poet per-ceived as the pernicious influences of Arabic culture:the heresies of Averroism and of the poetry of selfishlove. His negative judgment of the former is emblema-tized by his depiction of Dis (the lower part of hell) as a

city of mosques (not, notes Menocal succinctly, "/r&emosques" [p. 126]) ringed by the circle of heretics andhaunted by the shades of those (like Frederick II ofSicily, and Dante's friend Guido Cavalcanti) who bearthe taint of Averroism. Elsewhere Mulrammad is cleftin two, a schismatic punished not 'as the prophet ofIslam qua distant and little-known faith, but rather as

the emblematic prophet and master of thc dangerousphilosophies and philosophers who . . . were tearingapart the Christian community" (p. 130). The poetryof courtly love-represented, in Dante's time, by thepoets of the scuola siciliano and their Italian followers(notably Cavalcanti), and to which both Dante's ZitaNuovo and Petrarch's Canzoniere provide counter-statements-is similarly emblematized by the pictureof Francesca, self-absorbed and oblivious to the suffer-ings of her lover in hell. Menocal also takes up thequestion of Dante's relationship to Muslim accounts ofthe mi'raj, available to him in the libro della scalaappended to Peter the Venerable's Toledan Collection,going beyond Asin's primitive conception of that rela-tionship (based on the equation of influence withcopying) to see in the Commedia an "anti-mi'riij"demonstrating the falsity of Islam and the superiorityof Christian belief. In this sense "Dante represents thevery crossroads in the European absorption of andreaction to Arabic factors in the medieval world"(p. 135, n. 2l)-a crossroads quite different than thatenvisioned by Curtius, where the centrality of LatinIearning precluded contact with non-Latin elements.

A final chapter,'Other Readers, Other Readings,"suggests further areas in which a revised narrative ofmedieval European literature would reveal its complex-ity and variety. Boccaccio's use of the story-tellingtradition transmitted to Europe wathe Disciplina Cleri-calis {a text which, along with others such as the l00INights, "should be part of . . . a systematic compara-tive investigation of narrativity in medieval story col-lections" [p. lal]); the development of such genres as

the poetic encyclopedia and the mixed prose-poetrygenre; the filiations of medieval European linguistic

350

philosophy with Arabic and Hebrew studies; and a

variety of other issues suggest themselves (one mightadd, as others have done, the influence of Easternelements on medieval romance and chanson de geste).

lnvestigation of such issues would reveal that Arabicculture is important, often central, to the Europeantradition, rather than peripheral.

"A reconstruction of our views and definitions ofwhat constitutes Spanish in this period is clearl-v as

necessary, and potentially as beneficial, as neu views

and definitions of what is European." Menocal con-cludes;

These two notions are, indeed, inextricably inter-twined. . . . If Hispanomedievalists shed light on the

marvels and glories of Andalus, on its uniqueness and

its decisive influence over the rest of Europe in rhis

formative period. .. then they will undoubtedly reap

the rewards. And if they help to establish that the

twelfth. the thirteenth, or the fourteenth centuries and

their literatures cannot be fully seen or clearly under-

stood without looking first where others looked, toSpain, then this different kind of Hispanism will cer-

tainly be central to European studies (p. 153).

This falling back into the narrow confines of His-panism rather than moving forward to confront thebroader implications of her own arguments, seems tome the chief limitation of Menocal's otherwise provoca-tive book, precisely because it returns the focus of thesort of comparative studies she advocates back to thepoint away from which her arguments implicitly lead:to European, and specifically "Spanish," literature, as

distinct and definable entities. Guill6n, discussing the"myth" of national literatures as psychological com-pensation "for injured pride, for the oppression ofthe individual, for the submission of the intellectual tothe state," questions whether, before 1750, a writer inthe Spanish language would consider himself Sponishin a modern sense (1971, 499-502), and argues that it isonly when "Western" and "European" literature cease

to be co-terminous, with the expansion of Europe andthe rise of modern nation-states, that the notion ofliterature as the bearer of national identity comes intobeing [ibid., 47 3-7 5). To speak of the "Spanish" litera-ture of the Middle Ages is to reinforce this mythifyingparadigm.

Further (Guill6n observes), if one of the projects ofcomparative studies is indeed to clarify the develop-ment of national literatures, another, more importantgoal is the search for literary universals, in preparationfor a history of literoture as a system co-existing with*l.her syst€ins (social, political, economic), ald which,

Journal af the American Orienral Society 111.2 (1991)

as a system, is more than an amalgam of its individualparts (ibid., 475tr.). "This search," he asserts, "willsurely depend on the assimilation of a great deal ofknowledge concerning the non-Western literatures, orto put it in academic terms, on the work of comparativeliterature scholars who have been trained as Oriental-ists" (ibid., ll4). While Guill6n's optimism in thisrespect is perhaps misplaced, as most orientalists are

reluctant to venture out of their narrow areas ofspecialization, this is clearly the direction in whichfuture comparative studies must proceed.

Thus it is not sufficient to re-incorporate Arab Spaininto the medieval European tradition, to render it"European" rather than rejecting it as a manifestationof the Other; for whatever new definition of what is

Eur,.ipean may be achieved, the West's basic perceptionof its own unique and normative "Westernness" willremain unchallenged. For the Arabist, moreover, theeffect is most likely to be the removal of Hispano- andSicuto-Arabic literature even further from the main-stream of Arabic studies, and to perpetuate the diffi-culty of undertaking comparative studies which wouldshed light on an as yet virtually unexamined question:the development of the vernacular literatures of theIslamic world.

To take an instance: is it pure coincidence that so

many of the thematic motifs and imagery of later(twelfth- to fourteenth-century) Andalusian and Sicil-ian Arabic lyrics (idealized love, bacchic motifs, theemphasis on gardens, flowers, and so on), a preferencefor brief lyrics over the formal qa;tda, the prevalenceof similar structural patterns (notably ring composi-tion), are reminiscent not only of Provengal poetry butof Persian poetry of the same period? Or do suchaffinities reflect a tendency of the vernacular literaturesto free themselves from canonical modes of discoursein favor of others more responsive to their particularcultural ambience? Is it coincidence that allegoricalnarratives and "vi'sionary recitals" developed in Anda-Iusia and in lran (as well as in Europe), but neverachieved great popularity in the Arab East?

Such questions demonstrate that the issues Menocalraises are by no means limited to Hispanic studies, andthat the implications of her call for a revision of thenarrative of medieval literary history (and of academiccurricula) go beyond a new definition of "European"literature. Comparatism is not an end in itself (howeverilluminating its findings may be), but a method, orrather a range of methods, whose validity must beconstantly tested by application to periods and to litera-tures other than those with respect to which they wereoriginally derived. Thus, for example, theories of nar-rativity based on studies of the novel, or of folklore,

T

I

I

I

--i;#EF!:

Metseut: Arabic Cuhure and Medieval European Literature 351

may be tested against examples of medieval story-telling; notions of genre may be modified by compari-son of Western schemes with thosc of systems whichclassify their genres somewhat differently, or whichlack one or another of the "essential" European forms(for example, epic or drama); ideas of lyric, its regis-ters and speaking voices, its structures and conventions,may be clarified in the light not only of lhe muwash-

shafia but of earlier Arabic and later Persian lyrics.While, as Menocal points out, such studies may ulti-mately reveal filiations between Europe and the East,their greater value lies in their contribution to ourunderstanding of literary systems in more generalterms.

This. then, is my first quibble with this entertainingand thought-provoking book: that its author draws

back from pursuing its full implications, and thus tosome extent falls victim to the myth she is concerned torefute, that of the centrality and normative status ofEuropean literature. My second is with the emphasison political motives (though these mlrst not be dis-counted) to the exclusion of other, perhaps more ordi-nary failings-one of these being, to my mind (afterintellectual indolence and the unexamined acceptance

of received opinion), that the intractibility of the textsthemselves (whose subtleties can never be accountedfor by philological analysis alone), coupled with insuffi-cient literary knowledge (especially of pre-modernliteratures) on which to base comparisons, leads to an

intellectual impasse in dealing with those texts, a mental

throwing-up of hands reflective of an inability to grap-

ple with them as literature. Our self-examination, as

orientalists, medievalists, or comparatists' must take

into account not only the ideological myths which

form our attitudes, but the methodological ones as

well; and the most significant myth which informs ourefforts may prove not to be that of "Westernness," butthat of objectivity, which proposes that a thing isknowable in isolation from its context. This is a myth

to which, happily, Menocal herself does not subscribe,

as her emphasis on the contextual nature of meaning

makes clear.In some ways, then, this book is disappointing; in

many others, however, and particularly in Menocal'sevocation of the polymorphic culture of the MiddleAges and her readings of various authors and texts, itis both stimulating and informative, and enriches ourunderstanding of the period. There is, inevitably per-

haps, a certain amount ofrepetition, the result perhaps

of the author's enthusiasm for her subject and her wish

to argue it comprehensivety; but there is no question ofher critical competence. Many important points are

brought out in the extensive notes, which themselves

make compulsive and compulsory reading. The book isthus of importance not only to specialists (whether

Hispanists or Arabists) but to generalists and compara-tists as well, as the issues which it raises have far-reaching implications for the historiography and criti-cism of the medieval world and its rich and variedliterary tradition.

REFERENCES

Curtius, Ernst Robert. 1973. European Literature ond the

l-atin Middle Ages.Tr. Willard Trask. Princtton: Prince-

ton Univ. Press.

Click. Thomas F. 1979. Islantic and Christian Spain in the

furh Iliddle,{ges. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

von Grurebaum, G. E. 1952. Avicenna's RisdlaJi ?-'r'J4 and

Courtly Love. "/1[ES 9:233-38.

Guill6n, Claudio. 1971. Literature as System: Essays Toward

the Theory of Literary Hbtory. Princeton: Princeton

Univ. Press.

Hodgson, M. G. S. 1974. The Yenture of Islam. 3 vols. Chi-cago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Jauss, Hans-Robert. 1982. Towards an Aesthetic of Recep-

tion.Tr. Timothy Bahti. Brighton: Harvester Press.

Lach, Donald M. 1977. Asia in the Making of Europe. 2 vols.

Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Menocal, Maria Rosa. 1981. Close Encounlers in Medieval

Provence: Spain's Role in the Birth ofTroubadour Poe-

try. Hbpanic Revie*' 49:43-64.

Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. Nex York: Random

House.

1984. The World, the Texr and rhe Critic. London:

Faber & Faber.

Schwab, Raymond. 1984. The Oriental Renaissance: Europe's

Rediscovery of Indio and rhe East, rc\A-1880. Tr. Gene

Pattenon-Black and Victor Reinking. New York: Colum-

bia Univ. Press.

Stetkevych, J. 1969. Arabism and Arabic Literature, Self-

View of a Profession. "I,VES 28:145-56.

1980. Arabic Poetry and Assorted Poetics. In Islczric

Studies: A Tradition and lts Problems, ed. Malcolm

H. Kerr. Pp. 103-23. Malibu: Undena