JSSH Vol. 10 (2) Sep. 2002

-

Upload

truongdieu -

Category

Documents

-

view

256 -

download

2

Transcript of JSSH Vol. 10 (2) Sep. 2002

ISSN: 0128-7702

P e r t a n i k a J o u r n a l o f

socialscienceHumanities

VOLUME 10 NO. 2SEPTEMBER 2002

A scientific journal published by Universiti Putra Malaysia Press

Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities

About the JournalPertanika, the pioneer journal of UPM, beganpublication in 1978. Since then, it has establisheditself as one of the leading multidisciplinary journalsin the tropics. In 1992, a decision was made tostreamline Pertanika into three journals to meetthe need for specialised journals in areas of studyaligned with the strengths of the university. Theseare (i) Pertanika Journal of Tropical AgriculturalScience (ii) Pertanika Journal of Science &Technology (iii) Pertanika Journal of Social Science& Humanities.

Aims and ScopePertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanitiesaims to develop as a flagship journal for the SocialSciences with a focus on emerging issues pertainingto the social and behavioral sciences as well as thehumanities, particularly in the Asia Pacific region.It is published twice a year in March and September

The objective of the jou rna l is to p romoteadvancements in the fields of anthropology,business studies, communications, economics,education, extension studies, psychology, sociologyand the humanities. Previously unpublished

| original, theoretical or empirical papers, analyticalreviews, book reviews and readers critical reactionsmay be submitted for consideration. Articles maybe in English or Bahasa Melayu.

Submission of ManuscriptThree complete clear copies of the manuscript areto be submitted to

The Chief EditorPertanika Journal of Social Science and HumanitiesUniversiti Putra Malaysia13400 UPM, Serdang, Selangor Darul EhsanMALAYSIATel: 0S-89468854 Fax: 05^9416172

| Proofs and OffprintsPage proofs, illustration proofs and the copy-editedmanuscript will be sent to the author. Proofs mustbe checked very carefully within the specified timeas they will not be proofread by the Press editors.

Authors will receive 20 offprints of each article anda copy of the journal. Additional copies can beordered from the Secretarv of the Editorial Board.

1 EDITORIAL BOARD

Prof. Dr. Abdul Rahman Md Aroff - Chief EditorFaculty of Human Ecology

Prof. Dr. Annuar Md. NasirFaculty of Economics & Management

Prof. Dr. Mohd. Ghazali MohayidinFaculty of Economics & Management

Prof. Dr. Hjh. Aminah Hj. AhmadFaculty of Education

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rozumah BaharudinFaculty of Human Ecology

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Abdul Halin HamidFaculty of Human Ecology

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rosli TalifFaculty of Modern Language Studies

Sumangala Pillai - SecretaryUniversiti Putra Malaysia Press

INTERNATIONAL PANEL MEMBERS

Published by Universiti Putra Malaysia PressISSN No: 0128-7702

Prof. Jean Louis FloriotInternational Graduate Institute of Agribusiness

Prof. Bina AgarwralUniversity Enclave India

Prof. V.T KingUniversity of Hull

Prof. Royal D. ColleCornell Unix)ersity, Ithaca

Prof. Dr. Linda J. NelsonMichigan State University

Prof. Dr. Yoshiro HatanoTokyo Cakugei University

Prof. Max LanghamUniversity of Florida

Prof. Mohamed AriffMonash I niversity Australia

Prof. Fred LuthansUniversity of Nebraska

Prof. D.H. RichieUniversity of Toledo

Prof. Gavin W. JonesAustralian National University

Prof. Dr. Lehman B. FlectherIowa State University

Prof. Ranee PL Lee(Ihinese University. Hotig Kong

Prof. Stephen H.K. YehUniversity ofHaiuaii at Manoa

Prof. Graham W. ThurgoodCalifornia State University

ARCHIVE COPY>/pncP r>n Not Remove)

PERTANIKA EDITORIAL OFFICEResearch Management Centre (RMC)

1 st Floor, IDEA Tower liUPM-MTDC, Technology Centre

Universiti Putra Malaysia43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Tel: +603 8947 1622, 8947 1619, 8947 1616

Pertanika Journal of Social Science & Humanities

Volume 10 Number 2 (September) 2002

Contents

Modelling the Volatility of Currency Exchange Rate Using GARCH 85Model - Choo Wei Chong, Loo Sin Chun and Muhammad Idrees Ahmad

The Influence of Value Orientations on Service Quality Perceptions in 97a Mono-Cultural Context: An Empirical Study of Malay UniversityStudents - Hazman Shah Abdullah and Razmi Chik

The Sociolinguistics of Banking: Language Use in Enhancing 109Capacities and Opportunities - Ain Nadzimah Abdullah and RosliTalif

Faktor-faktor Mempengaruhi Agihan Pendapatan di Malaysia 1970- 1172000 - Rahmah Ismail dan Poo Bee Tin

Performances of Non-linear Smooth Transition Autoregressive and 131Linear Autoregressive Models in Forecasting the Ringgit-Yen Rate- Liew Khim Sen and Ahmad Zubaidi Baharumshah

Interpretation of Gender in a Malaysian Novel: The Case of Salina 143- Jariah Mohd. Jan

Penterjemahan Pragmatik dalam Konsep Masa Arab-Melayu: Satu 153Analisis Teori Relevan - Muhammad Fauzi bin Jumingan

Tingkah Laku Keibubapaan dan Penyesuaian Tingkah Laku Anak 165dalam Keluarga Berisiko di Luar Bandar - Zarinah Arshat, RozumahBaharudin, Rumaya Juhari dan Rojanah Kahar

Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. & Hum. 10(2): 85-95 (2002) ISSN: 0128-7702© Universiti Putra Malaysia Press

Modelling the Volatility of Currency Exchange Rate Using GARCH Model

CHOO WEI CHONG, LOO SIN CHUN & MUHAMMAD IDREES AHMADFaculty of Economics & Management

Universiti Putra Malaysia43400 UPM, Serdang, Selangor

E-mail: [email protected]

Keywords: Exchange rates, volatility, forecasting, GARCH, random walk

ABSTRAKKertas ini mengkaji model GARCH dan modifikasinya dalam menguasai kemeruapan kadarpertukaran mata wang. Parameter model tersebut dianggar dengan menggunakan kaedahkebolehjadian maksimum. Prestasi bagi penganggaran dalam sampel didiagnosis denganmenggunakan beberapa statistik kebagusan penyuaian dan kejituan telahan satu langkah kedepan dan luar sampel dinilai dengan menggunakan min ralat kuasa dua. Keputusan kajianmenunjukkan kegigihan kemeruapan kadar pertukaran mata wang RM/Sterling. Keputusandaripada penganggaran dalam sampel menyokong kebergunaan model GARCH dan modelvariasi malar pula ditolak, sekurang-kurangnya dalam sampel. Statistik Q dan ujian pendarabLangrange (LM) mencadangkan penggunaan model GARCH yang beringatan panjangmenggantikan model ARCH yang beringatan pendek dan berperingkat lebih tinggi. ModelGARCH-M pegun berprestasi lebih tinggi daripada model GARCH lain yang digunakan dalamkajian ini, dalam telahan satu langkah ke depan dan luar sampel. Apabila menggunakan modelperjalanan rawak sebagai tanda aras, semua model GARCH berprestasi lebih baik daripada modeltanda aras ini dalam meramal kemeruapan kadar pertukaran mata wang RM/Sterling.

ABSTRACT

This paper attempts to study GARCH models with their modifications, in capturing the volatilityof the exchange rates. The parameters of these models are estimated using the maximumlikelihood method. The performance of the within-sample estimation is diagnosed using severalgoodness-of-fit statistics and the accuracy of the outof-sample and one-step-ahead forecasts isevaluated using mean square error. The results indicate that the volatility of the RM/Sterlingexchange rate is persistent. The within sample estimation results support the usefulness of theGARCH models and reject the constant variance model, at least within-sample. The Q-statistic andLM tests suggest that long memory GARCH models should be used instead of the short-termmemory and high order ARCH model. The stationary GARCH-M outperforms other GARCHmodels in out-of-sample and one-step-ahead forecasting. When using random walk model as thenaive benchmark, all GARCH models outperform this model in forecasting the volatility of theRM/Sterling exchange rates.

INTRODUCTIONIssues related to foreign exchange rate havealways been the interest of researchers inmodern financial theory. Exchange rate, whichis the price of one currency in terms of anothercurrency, has a great impact on the volume offoreign trade and investment. Its volatility hasincreased during the last decade and is harmfulto economic welfare (Laopodis 1997). The

exchange rate fluctuated according to demandand supply of currencies. The exchange ratevolatility will reduce the volume of internationaltrade and the foreign investment.

Modelling and forecasting the exchange ratevolatility is a crucial area for research, as it hasimplications for many issues in the arena offinance and economics. The foreign exchangevolatility is an important determinant for pricing

Choo Wei Chong, Loo Sin Chun & Muhammad Idrees Ahmad

of currency derivative. Currency options andforward contracts constitute approximately halfof the U.S. 880bn per day global foreignexchange market (Isard 1995). In view of this,knowledge of currency volatility should assistone to formulate investment and hedgingstrategies.

The implication of foreign exchange ratevolatility for hedging strategies is also a recentissue. These strategies are essential for anyinvestment in a foreign asset, which is acombination of an investment in theperformance of the foreign asset and aninvestment in the performance of the domesticcurrency relative to the foreign currency. Hence,investing in foreign markets that are exposed tothis foreign currency exchange rate risk shouldhedge for any source of risk that is notcompensated in terms of expected returns (Santisetal 1998).

Foreign exchange rate volatility may alsoimpact on global trade patterns that will affect acountry's balance of payments position and thusinfluence the government's national policy-making decisions. For instance, Malaysia fixedthe exchange rate at RM3.80/US$ in September,1998, due to the economic turmoil and currencycrisis in 1997. This turmoil has spread todeveloped countries such as USA, Hong Kong,Europe and other developing South Americancountries such as Brazil and Mexico. Due to thiscurrency crisis, various governments haveresorted to different national policies so as tomitigate the effect of this crisis.

In international capital budgeting ofmultinational companies, the knowledge offoreign exchange volatility will help them inestimating the future cash flows of projects andthus the viability of the projects.

Consequently, forecasting the futuremovement and volatility of the foreign exchangerate is crucially important and of interest tomany diverse groups including marketparticipants and decision makers.

Beginning with the seminal works ofMandelbrot (1963a, 1963b, 1967) and Fama(1965), many researchers have found that thestylized characteristics of the foreign currencyexchange returns are non-linear temporaldependence and the distribution of exchangerate returns are leptokurtic, such as Friedmanand Vandersteel (1982), Bollerslev (1987),Diebold (1988), Hsieh (1988, 1989a, 1989b),

Diebold and Nerlove (1989), Baillie andBollerslev (1989). Their studies have found thatlarge and small changes in returns are ' clustered'together over time, and that their distribution isbell-shaped, symmetric and fat-tailed.

These features of data are normally thoughtto be captured by using the AutoregressiveConditional Heteroskedasticity (ARCH) modelintroduced by Engle (1982) and the GeneralisedARCH (GARCH) model developed by Bollerslev(1986), which is an extension of the ARCHmodel to allow for a more flexible lag structure.The use of ARCH/GARCH models and itsextensions and modifications in modeling andforecasting stock market volatility is now verycommon in finance and economics, such asFrench et al (1987), Akgiray (1989), Lau et al(1990), Pagan and Schwert (1990), Day andLewis (1992), Kim and Kon (1994), Frames andVan Dijk (1996) and Choo et al (1999).

On the other hand, the ARCH model wasfirst applied in modeling the currency exchangerate by Hsieh only in 1988. In a study done byHsieh (1989a) to investigate whether dailychanges in five major foreign exchange ratescontain any nonlinearities, he found thatalthough the data contain no linear correlation,evidence indicates the presence of substantialnonlinearity in a multiplicative rather thanadditive form. He further concludes that ageneralized ARCH (GARCH) model can explaina large part of the nonlinearities for all fiveexchange rates.

Since then, applications of these models tocurrency exchange rates have increasedtremendously, such as Hsieh (1989b), Bollerslev,T. (1990), Pesaran and Robinson (1993),Copeland et al (1994), Takezawa (1995),Episcopos and Davies (1995), Brooks (1997),Hopper (1997), Cheung et al. (1997), Laopodis(1997), Lobo etal (1998) and Duan etal (1999).

In many of the applications, it was foundthat a very high-order ARCH model is requiredto model the changing variance. The alternativeand more flexible lag structure is the GeneralisedARCH (GARCH) introduced by Bollerslev(1986). Bollerslev et al (1992) indicated thatthe squared returns of not only exchange ratedata, but all speculative price series, typicallyexhibit autocorrelation in that large and smallerrors tend to cluster together in contiguoustime periods in what has come to be known asvolatility clustering. It is also proven that small

86 PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002

Modelling the Volatility of Currency Exchange Rate Using GARCH Model

lag such as GARCH (1,1) is sufficient to modelthe variance changing over long sample periods(French et al 1987; Franses and Van Dijk 1996;Choo et al. 1999).

Even though the GARCH model caneffectively remove the excess kurtosis in returns,it cannot cope with the skewness of thedistribution of returns, especially the financialtime series which are commonly skewed. Hence,the forecasts and forecast error variances from aGARCH model can be expected to be biased forskewed time series. Recently, a few modificationsto the GARCH model have been proposed, whichexplicitly take into account skewed distributions.One of the alternatives of non-linear modelsthat can cope with skewness is the ExponentialGARCH or EGARCH model introduced byNelson (1990). For stock indices, Nelson'sexponential GARCH is proven to be the bestmodel of the conditional heteroskedasticity.

In 1987, Engle et aL developed the GARCH-Mto formulate the conditional mean as functionof the conditional variance as well as anautoregressive function of the past values of theunderlying variable. This GARCH in the mean(GARCH-M) model is the natural extension dueto the suggestion of the financial theory that anincrease in variance (risk proxy) will result in ahigher expected return.

Choo et al. (1999) studies the performanceof GARCH models in forecasting the stockmarket volatility and they found that i) thehypotheses of constant variance models couldbe rejected since almost all the parameterestimates of the non-constant variance (GARCH)models are significant at the 5% level; ii) theEGARCH model has no restrictions andconstraints on the parameters; iii) the long-memory GARCH model is more suitable thanthe short-memory and high-order ARCH modelin modelling the heteroscedasticity of thefinancial time series; iv) the GARCH-M is best infitting the historical data whereas the EGARCHmodel is best in outof-sample (one-step-ahead)forecasting; v) the IGARCH is the poorest modelin both aspects.

Since Choo et aL (1999) have indicated thatthe GARCH-M model performs well in within-sample estimation and the EGARCH modelperforms best in outof-sample forecasting, thecombination of both models, EGARCH-M shouldbe able to enhance the performance in bothaspects.

In order to know the out-of-sampleforecasting performance of EGARCH-M, wecompare the performance of EGARCH-M andthe other modifications of the GARCH model tothe simple random walk forecasting scheme.

The models are presented in the followingsection. The third section is the background ofcurrency exchange rate data and themethodology used in this study. All the resultswill be discussed in the fourth section. Theconclusion will be in the final section.

MODELThe conditional distribution of the series ofdisturbances which follows the GARCH processcan be written as

s/^ ~ N(0,A,)

where iptl denotes all available informationat time f- 1. The conditional variance h is

Hence, the GARCH regression model forthe series of rt can be written as

-(p]B-K -<f>sBs

et~N{0,l)

iy-i

where B is the backward shift operatordefined by &yt = yt- k. The parameter pi reflectsa constant term, which in practice is typicallyestimated to be close or equal to zero. Theorder of s is usually 0 or small, indicating thatthere are usually no opportunities to forecast r(

from its own past. In other words, there is alwaysno auto-regressive process in r(.

1) ARCH

The GARCH (p,q) model is reduced to theARCH(q) model when p = 0 and at least one ofthe ARCH parameters must be nonzero (q > 0).

PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. 8c Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002 87

Choo Wei Chong, Loo Sin Chun & Muhammad Idrees Ahmad

2) Stationary GARCH, SG(p,q)

If the parameters are constrained such that

Z ai + X &j < 1 > they imply the weakly stationaryi-\ j-\

GARCH (SG(p,q)) model since the mean,variance and autocovariance are finite andconstant over time.

3) Unconstrained GARCH, UG(p,q)The parameter of w, a. and ft can beunconstrained, thus yielding the unconstrainedGARCH (UG(p,q)) model.

4) Non-negative GARCH\ NG(p,q)

If p * 0 , q > 0 and w > 0, a :> 0, p. * 0, yieldsthe non-negative GARCH (NG{p,q)) model.

5) Integrated GARCH, IG(p,q)

Sometimes, the multistep forecasts of the variancedo not approach the unconditional variancewhen the model is integrated in variance; that is

,• + 2 0 ; " 1 * Th e unconditional variance for

the IGARCH model does not exist. However, itis interesting that the integrated GARCH orIGARCH (IG(p,q)) model can be stronglystationary even though it is not weakly stationary(Nelson 1990a, b).

6) Exponential GARCH, EG(p,q)

The exponential GARCH or EGARCH (EG(p,q))model was proposed by Nelson (1991). Nelsonand Cao (1992) argue that the nonnegativityconstraints in the linear GARCH model are toorestrictive. The GARCH model imposes thenonnegative constraints on the parameters, a.and /3, while there is no restriction on theseparameters in the EGARCH model. In theEGARCH model, the conditional variance, ht, isan asymmetric function of lagged disturbances,

The coefficient of the second term in g(Z;)is set to be 1 (y = 1) in this formulation. Notethat E/Z/= (2/JT)1 / 2 if Z{ ~ N(0,l).

7) GARCH-in-Mean, G(p,q)-M

The GARCH-in-Mean, G(p,q)-M model has theadded regressor that is the conditional standarddeviation

r{ =

et =et

where kt follows the GARCH process.

8) Stationary GARCH-in-Mean, SG(p,q)-M

This model has the added regressor that is theconditional standard deviation

r, -

where h( follows the stationary GARCH,process.

9) Unconstrained GARCH-in-Mean, UG(p,q)-M

This model has the added regressor that is theconditional standard deviation

r, =

et =

where ht follows the unconstrained GARCH,UG(p,q) process.

10) Non-negative GARCH-in-Mean, NG(p,q)-M

This model has the added regressor that is theconditional standard deviation

ln{h,) - w +

where where k( follows the non-negative GARCH,NG(p,q) process.

11) Integrated GARCH-in-Mean, IG(p,q)-M

This model has the added regressor that is theconditional standard deviation

88 PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. 8c Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002

Modelling the Volatility of Currency Exchange Rate Using GARCH Model

where ht follows the integrated GARCH,\G{p,q) process.

12) Exponential GARCH-in-Mean, EGip,q)-M

This model has the added regressor that is theconditional standard deviation

where h( follows the exponential GARCH,EG(pyq) process.

Since a small lag of the GARCH model issufficient to model the long-memory process ofchanging variance (French et al. 1987; Fransesand Van Dijk 1996; Choo et al 1999), theperformance of GARCH models in forecastingRM-Sterling exchange rate volatility is evaluatedby using SG(1,1), UG(1,1), NG(1,1) IG(1,1),

NG(1,1)-M, IG(1,1)-M, and EG(1,1)-M.

DATA AND METHODOLOGYIn this study, simple rate of returns is employedto model the currency exchange rate volatility ofRM-Sterling. Consider a foreign exchange rateEt, its rate of return r(, is constructed as

E - Ert = —- —. The exchange rate t denotes daily

exchange rate observations.The foreign exchange rate used in this study

is focused on the Malaysian Ringgit (RM) to thePound Sterling. This exchange rate is chosenbecause in addition to the US dollar, the PoundSterling is also one of the major currenciestraded in the foreign exchange markets.Traditionally and historically, the UK has always

been one of the important trading partners ofMalaysia. The data was collected from 2 January1990 to 13 March 1997, from 1810 observations.The daily closing exchange rates were used asthe daily observations. The first 1760 observationsare used for parameters estimation and the last50 observations reserved for forecastingevaluation.

Fig. 1 shows nearly 1810 daily observer crossrates of the Malaysian Ringgit to the PoundSterling, covering the seven years from 2 January1990 to 13 March 1997. Some characteristics ofthe rate of returns, r, are given in Table 1. Themeans and variances'are quite small. The excesskurtosis indicates the necessity of fat-taileddistribution to describe these variables. Theskewness of-0.200 indicates that the distributionof rate of returns for RM-Sterling is negativelyskewed.

The family of GARCH models is estimatedusing the maximum likelihood method. Thismethod enables the rate of return and varianceprocesses being estimated jointly. The log-likelihood function is computed from theproduct of all conditional densities of theprediction errors.

where et = r - fi and h( is the conditionalvariance. When the GARCH{p,q)-M model is

estimated, et = rt - \i ~ b^ht . When there are no

regressors (trend or constant, [i the residuals et

are denoted as r or r( - rt - dfy. The likelihood

function is maximized via the dual quasi-Newtonand trust region algorithm. The starting valuesfor the regression parameters \x are obtainedfrom the OLS estimates. When there areautoregressive parameters in the model, theinitial values are obtained from the Yule-Walker

TABLE 1Summary statistics of currency exchange rate data on rate of returns from 2 January 1990 to

13 March 1997

Currency ExchangeRate

RM/Sterling

n

1809

Mean( x 10-5 )

-3.183

Variance( x 10-5 )

4.076

Skewness

-0.200

ExcessKurtosis

2.370

Source of data: The Federal Reserve, the Central Bank of the United States

PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. 8c Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002 89

Choo Wei Chong, Loo Sin Chun & Muhammad Idrees Ahmad

t 183 365 547 729 911 1093 1275 1457 1639

92 274 456 638 820 1002 1184 1366 ! 548 ! 730

Time in trading day units

Fig. 1: RM/Sterling, daily from 2 January 1990 to 13 March 1997

estimates. The starting value IE - 6 is used forthe GARCH process parameters. The variance-covariance matrix is computed using the Hessianmatrix. The dual quasi-Newton methodapproximated the Hessian matrix while the quasi-Newton method gets an approximation of theinverse of Hessian. The trust region methoduses the Hessian matrix obtained using numericaldifferentiation. This algorithm is numericallystable, though computation is expensive.

In order to test for the independence of theindices series, the portmanteau test statistic basedon squared residual is used (McLeod and Li1983). This Q statistic is used to test the non-linear effects, such as GARCH effects, present inthe residuals. The GARCH {p,q) process can beconsidered as an ARMA (m3x(p,q),p) process.Therefore, the Q statistic calculated from thesquared residuals can be used to identify theorder of the GARCH process. The Lagrangemultiplier test for ARCH disturbances is proposedby Engle (1982). The test statistic is asymptoticallyequivalent to the test used by Breusch and Pagan(1979).

The LM and Q statistics are computed fromthe OLS residuals assuming that disturbance iswhite noise. The Q and LM statistics have anapproximate (^ ) distribution under the whitenoise null hypotheses.

Various goodnessof-fit statistics are used tocompare the six models in this study. Thediagnostics are the mean of square error (MSE),the loglikelihood (Log L), Schwarz's Bayesianinformation criterion (SBC) by Schwarz (1978)and Akaike's information criterion (AIC) (Judgeet ai 1985).

The 'true volatility' is measured to evaluatethe performance of the six GARCH models inforecasting the volatility in stock returns. As inthe studies by Pagan et ai (1990) and Day et ai(1992), the volatility is measured by

where ris the average return. The measureof the one-step-ahead forecast error is

where hM is generated using the h( equationsof the GARCH models being studied. Theestimated parameters of the GARCH modelssuch as w, or, jS, 6 and 6 are substituted during

the generation of ht+l. In order to show theperformance of GARCH models over a naive no-change forecast, the forecast errors of therandom walk (RW) are calculated as follows:

~ vc

This is a very important naive benchmark inthe comparison of the forecasts from the GARCHmodels (Brooks 1997).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONParameter Estimations

The parameter estimates for eleven variations ofGARCH models of the rate of returns series arepresented in Table 2 (a) and Table 2 (b). Thesewithin-sample estimation results enable us toknow the possible usefulness of the GARCH

90 PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002

Modelling the Volatility of Currency Exchange Rate Using GARCH Model

models in modeling the currency exchange rateseries.

It can be seen from Table 2 (a) that exceptfor \i, all the parameter estimates of the RM/Sterling (w> a and p) are significant at 5% level.However, in Table 2(b), all the two additionalparameter estimates (5 and 6) of the EGARCHand all the GARCH models with means are notsignificant. It appears that for the within-sampleestimations, all the family GARCH modelsperform well in modeling the exchange rate ofRM/Sterling.

In general, it can be concluded that almostall a and fi (ARCH and GARCH terms) of theRM/Sterling series examined are significant.Hence, the constant variance model can berejected, at least for the within-sample estimation.

For the linear GARCH models such as SG(1,1),the sum of a and p is close to unity. Theproperties of + = 1 of IG(1,1) also hold for theseries.

Diagnostics Checking

The basic ARCH (q) model is a short memoryprocess in that only the most recent q squaredresiduals are used to estimate the changingvariance. The results for Q statistic and LagrangeMultiplier (LM) test are shown in Table 3. Thesecan help to determine the order of the ARCHprocess in modeling the RM/Sterling series.

The tests are significant at less then 1%level though order 12. These indicate that theheteroscedasticity terms of the daily RM/Sterlingexchange rate series needed to be modeled by a

TABLE 2 (a)Estimation results of rate of returns for the currency exchange rate

CurrencyExchange Rate Model

Parameter estimates

t Ratio t Ratio

RM/Sterling

-0.125-0.125-0.125-0.125-0.104-0.056

-1.305-1.308-1.306-1.306-1.229-0.622

-0.047

-0.093

-0.518

TABLE 2(b)Estimation results of rate of returns for the currency exchange rate

CurrencyExchangeRate

Model

Parameter estimates

t Ratio co(xlO^) t Ratio a t Ratio(xlO-4)

t Ratio

RM/Sterling 1.61.61.6

1.421.068.368.388.378.377.116.03

1.2461.2431.2431.1120.7871.5591.561.561.561.528

0.7720.7640.7640.350

-291080.00.7580.7650.7560.7560.347

-294460.0

4.7494.6994.6994.842-2.5044.7544.8024.7444.7444.904-2.709

0.0720.0720.0720.0760.1620.0710.0700.0710.0710.0760.163

9.0879.0619.06

10.2116.5889.0069.0349.0059.00510.166.664

0.9100.9100.9100.9240.9710.9110.9110.9110.9110.9240.970

93.61893.69793.678123.44285.15394.63

94.66794.65394.646124.18891.004

PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002 91

Choo Wei Chong, Loo Sin Chun & Muhammad Idrees Ahmad

Diagnostics for

CurrencyExchange Rate

rm/pound

currency exchange

Q(12)

273.447

TABLE 3rate using Q statistic and Lagrange

Diagnostics

Prob>Q(12) LM(12)

0.0001 147.373

Multiplier test

Prob>LM(12)

0.0001

very high order of ARCH model. These resultssupport the use of GARCH model, which allowslong memory processes to estimate the currentvariance of the daily RM/Sterling series insteadof the ARCH model.

Goodness of Fit Tests

The result of the goodness-of-fk statistics for theRM/Sterling series is presented in Table 4. Table5 shows the rankings of various GARCH models.

From Table 5, the ranking of the MSE valueindicates that all the family of GARCH in meanmodels outperform the GARCH models with aslight value of 0.000001. The Log L valueshowever, suggest EG(1,1)-M to be the best modelfor modeling the volatility of RM/Sterling,followed by UG(1,1)-M, NG(1,1)-M andG(l,l)-M. The SBC values in contrast, rankedindifferently SG(1,1), UG(1,1) and NG(1,1) tobe the best model followed by IG(1,1). The AICvalues on the other hand, proposed UG(1,1)and NG(1,1) to be the best two models, followedby SG(U).

From the goodnessof-fit test, it appears thatfor within-sample estimations, almost all theGARCH models outperform the GARCH in mean

models in the SBC and AIC test while in theMSE and Log L test, all the GARCH in meanmodels perform well to model the daily exchangerate compared to their ordinary GARCH modelcounterparts.

One Step Ahead Forecasting

The good performance in the parameterestimation and goodness-of-fit statistics do notguarantee the good performance in forecasting(Choo et ai 1999). The performance of theGARCH models is evaluated through the one-step-ahead forecasting. 50 one-step-aheadforecasts are generated and the mean squareerror (MSE) is calculated to evaluate theforecasting performance. The results of theforecasting for the GARCH models and therandom walk model are shown in Table 6. Therankings of the models based on the performanceof the one-step-ahead forecasting are presentedin Table 7.

In Table 7, the ranking results of MSEsuggest that SG(1,1)-M is the best model forone-step-ahead forecasts, followed by SG(1,1)and G(l,l)-M. It is also noted that, SG(1,1)-M,UG(1,1)-M and NG(1,1)-M clearly outperform

TABLE 4Goodness-of-fit statistics on rate of returns for the currency exchange rates

CurrencyExchangeRate

Rm/pound

Model

SG(1,1)UG(1,1)NG(1,1)IG(1,1)EG(1,1)G(l,l)-MSG(1,1)-MUG(1,1)-MNG(ltl)-MIG(1,1)-MEG(1(1)-M

MSE(xlO-4)

0.410.410.410.410.410.400.400.400.400.400.40

Goodness-of-Fit Statistics

LogL

6525.3716525.4146525.4146521.1516525.7296526.2716526.2326526.2836526.2836521.9926526.674

SBC

-13020.9-13020.9-13020.9-13019.9-13014.1-13015.2-13015.1-13015.2-13015.2-13014.1-13008.5

AIC

-13042.7-13042.8-13042.8-13036.3-13041.5-13042.5-13042.5-13042.6-13042.6-13036

-13041.3

92 PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002

Modelling the Volatility of Currency Exchange Rate Using GARCH Model

TABLE 5Rankings of the models averaged across the currency exchange based on the performance of

various goodness-of-fit statistics

RM/pound

Model MSE Log L SBC AIC

7 9 1 3

) 7 7 1 1) 7 7 1 1

7 11 4 107 6 9 8

VI 1 4 5 6- M l 5 8 6)-M 1 2 5 4)-M 1 2 5 4- M l 10 9 11i-M 1 1 11 9

TABLE 6Out-of-sample forecasting performance of various GARCH models and random

walk models for the volatility of the currency exchange rates

MSE (xlO-9) of one-step-ahead forecast (forecast period = 50)

Model RM/pound

3.0803.0893.0893.6073.1493.0853.0753.0873.0873.6253.150

RW 6.849

TABLE 7Rankings of the models averaged across the currency exchange rates

based on the performance of one-step-ahead forecasting

Model MSE of one-step-ahead forecast for RM/pound

SG(U) 2) 7) 6

108

VI 3- M 1)-M 4I-M 5•M 11-M 9

RW 12

PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002 93

Choo Wei Chong, Loo Sin Chun & Muhammad Idrees Ahmad

their ordinary GARCH models counterparts whileEG(1,1) and IG(1,1), in contrast, outperformtheir with mean GARCH counterparts.

In general, almost all the GARCH in meanmodels outperform the ordinary GARCH modelswith the exception of EG(1,1) and IG(1,1).However, the family of GARCH models is clearlybeing proposed instead of their naive benchmark,the random walk model.

CONCLUSIONUsing seven years of daily observed RM/Sterlingexchange rate, the performance of GARCHmodels, including the family of GARCH in meanmodels to explain the commonly observedcharacteristics of the unconditional distributionof daily rate of returns series, were examined.

The results indicate that the hypotheses ofconstant variance model could be rejected, atleast within-sample, since almost all the parameterestimates of the ARCH and GARCH models aresignificant at 5% level.

The Q statistics and the Lagrange Multipliertest reveal that the use of the long memoryGARCH model is preferable to the short memoryand high-order ARCH model.

The results from various goodness-of-fitstatistics are not consistent for RM/Sterlingexchange rates. It appears that the SBC and AICtest proposed GARCH models to be the best forwithin-sample modeling while the MSE and LogL test, suggest the GARCH in mean models tobe best to model the heteroscedasticity of dailyexchange rates.

The forecasting results show that SG(1,1)-Mis the best model for forecasting purpose,followed by SG(1,1) and G(l,l)-M. Almost allthe GARCH in mean models outperform theordinary GARCH models. On the other hand,the family of GARCH models has clearly shownthat they perform better than the naivebenchmark, the random walk model.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe would like to thank the anonymous refereesand reviewers of this paper who have providedus with many useful comments and suggestions.This research was supported by the short termresearch grant funded by the Ministry of Science,Technology and the Environment, Malaysia,through the Faculty of Economics andManagement, Universiti Putra Malaysia.

REFERENCESAKGIRAY, V. 1989. Conditional heteroskedasticity in

time series of stock returns: Evidence andforecasts. Journal of Business 62: 55-80.

BAILLIE, R. T. and T. BOLLERSLEV. 1989. The messagein daily exchange rates : A conditional variancetele. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics7: 297-305.

BOLLERSLEV, T. 1986. Generalized autoregressiveconditional heteroskedasticity. Journal ofEconometrics 31: 307-327.

BOLLERSLEV, T. 1987. A conditional heteroskedastictime series model for speculative prices andrates of return. Review of Economics and Statistics69: 542-547.

BOLLERSLEV, T. 1990. Modelling the coherence inshort-run nominal exchange rates: Amultivariate generalized ARCH model. TheReview of Economics and Statistics:. 498-504.

BOLLERSLEV, T., R. Y. CHOU and K. F. KRONER. 1992.Arch modelling in finance. A review of thetheory and empirical evidence. Journal ofEconometrics 52: 5-59.

BRCX)KS, C. and S. P. BURKE. 1998. Forecastingexchange rate volatility using conditionalvariance models selected by informationcriteria. Economics Letters 61: 273-278.

CAPORALE, G. M. and N. Prrris. 1996. Modellingsterling-deutschmark exchange rate: Non-lineardependence and thick tails. Economic Modelling13: 1-14.

CHEN, A. S. 1997. Forecasting the S & P 500 indexvolatility. International Review of Economics &Financed: 391-404.

CHEUNG, Y. W. and C Y. P. WONG. 1997. Theperformance of trading rules on four Asiancurrency exchange rates. Multinational FinanceJournal 1(1): 1-22.

CHOO, W. C, M. I. AHMAD and M. Y. ABDULLAH.1999. Performance of GARCH models inforecasting stock market volatility. Journal ofForecasting 18: 333-343.

COPKIAND, L. S. and P. WANG. 1994. Estimating dailyseasonality in foreign exchange rate changes.Journal of Forecasting 13(6): 519-528.

DAY, T. E. and C. M. LEWIS. 1992. Stock marketvolatility and information content of stockindex options. Journal of Econometrics 52: 267-287.

94 PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002

Modelling the Volatility of Currency Exchange Rate Using GARCH Model

DIEBOLD, F. X. and M. NERLOVE. 1989. The dynamicsof exchange rate volatility : A multivariatelatent variable factor ARCH model. Journal ofApplied Econometrics 4(1): 1-21.

DIEBOLD, F. X. 1988. Empirical Modeling of ExchangeRate Dynamics. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

DUAN , J. C. and Z. W.JASON. 1999. Pricing foreigncurrency and cross-currency options underGARCH. The Journal of Derivatives (Fall).

ENGLE, R. F. 1982. Autoregressive conditionalheteroskedasticity with estimates of the varianceof U.K. inflation. Econometrica 50: 987-1008.

ENGLE, R. F., M. L. DAVID and P. R. RUSSEL. 1987.Estimating time varying risk premia in theterm structure: The ARCH-M model.Econometrica 55: 391-407.

EPISC;OPOS, A. and J. DAVIKS. 1995. Predicting returnson Canadian exchange rates with artificialneural networks and EGARCH-M models.Neural Computing and Applications (forthcoming).

FRENCH, K. R., G. W. SCHWERT and R. F. STAMBAUGH.1987. Expected stock returns and volatility.Journal of Financial Economics 19: 3-30.

FRIEDMAN, D. and S. VANDERSTEEL. 1982. Short-runfluctuations in foreign exchange rates :Evidence from the data 1973 - 1979. Journal ofInternational Eonomics 13: 171-186.

HOPPER, G. P. 1997. What determines the exchangerate: Economics factors or market sentiment.Business Review: 17-29. Federal Reserve Bank ofPhiladelphia.

HSIEH, D. A. 1988. The statistical properties of dailyforeign exchange rates: 1974 - 1983. Journal ofInternational Economics: 129-145.

HSIEH, D. A. 1989a. Modeling hetereskedasticity indaily foreign exchange rates. Journal of Businessand Economic Statistics 7: 306-317.

HSIEH D. A. 1989b. Testing for non-lineardependence in daily foreign exchange rates.Journal of Business 62: 339-368.

LAOPODIS, N. T. 1997. U.S. dollar asymmetry andexchange rate volatility. Journal of AppliedBusiness Research 13(2) Spring: 1-8.

LAU, A., H. LAU and J. WINGENDER. 1990. Thedistribution of stock returns : New evidenceagainst the stable model. Journal of Businessand Economic Statistics 8 (April): 217-223.

LOBO, B. J. and D. TUFTE. 1998. Exchange ratevolatility: Does politics matter? Journal ofMacroeconomics 20(2) Spring: 351-365.

MCKENZIE, M. D. 1999. Power transformation andforecasting the magnitude of exchange ratechanges. International Journal of Forecasting 15:49 - 55.

PESARAN, B. and G. ROBINSON. 1993. The Europeanexchange rate mechanism and the volatility ofthe sterling-deutschmark exchange rate.Economic Journal 103: 1418-1431.

SANTIS, G. D. and B. GERARD. 1998. How big is thepremium for currency risk. Journal of FinancialEconomics 49: 375-412.

TAKEZAWA, N. 1995. A note on intraday foreignexchange volatility and the informational roleof quote arrivals. Economics Letters 48: 399-404.

TAYLOR, S. J. 1986. Modelling Financial Time Series.New York: Wiley.

(Received: 11 June 2001)

PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002 95

Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. & Hum. 10(2): 97-107 (2002) ISSN: 0128-7702© Universiti Putra Malaysia Press

The Influence of Value Orientations on Service Quality Perceptions in aMono-Cultural Context: An Empirical Study of Malay University Students

HAZMAN SHAH ABDULLAH 8c RAZMI CHIKFaculty of Administrator & Law

Universiti Teknologi MARA40450 UiTM Shah Alam

Selangor, Malaysia

Keywords: Service quality, culture studies, value variations, variance analysis

ABSTRAK

Kajian hubungan mutu perkhidmatan dan nilai-budaya telah secara tradisi menggunakan kaedahantara budaya untuk membuktikan kesannya. Tujuan kajian ini ialah untuk menunjukkan bahawaterdapat perbezaan yang penting dalam sesuatu budaya dan perbezaan ini mempunyai implikasiterdapat reka bentuk, penyediaan dan mutu perkhidmatan. Selaras dengan pendirian ini, kajianini menyelidiki nilai-budaya dalam konteks suatu kumpulan budaya tertentu. Kajian melibatkanseramai 712 siswa-siswi Bumiputera sebuah universiti tempatan telah menghasilkan 2 gugusannilai yang signifikan. Analisis varian menunjukkan bahawa gugusan 'True Traditionalists'dan 'Transitory Traditionalists' memperlihatkan kesan yang berbeza kepada dimensi mutuperkhidmatan. Hasil kajian menyokong pendirian bahawa kajian hubungan budaya-mutuperkhidmatan mestilah juga fokus kepada perbezaan dalam sesuatu budaya.

ABSTRACT

Service quality and culture studies have traditionally used polar opposite cultures to make theircase. This paper argues that these cultural extremes conceal significant variations in culture andhas implications for service design, delivery and quality. The study explores the existence of valuevariations within ostensibly homogenous groups. It is posited that the knowledge of thesespectrum of value orientations will enhance the service marketers' ability to 'situate' services asthey enter new markets or introduce service innovations. A study conducted among 712 Malayuniversity students produced 2 significantly different value clusters. Variance analysis showed thatthese clusters labeled as True Traditionalist and Transitory Traditionalist have significantlydifferent impact on service quality dimensions. The findings support the argument that servicequality and culture studies must examine between as well as within culture variations.

INTRODUCTIONThe rapid extension of service products to globalmarkets has invoked the question of situatingthe services in the local cultural and socialenvironment (Matilla 1999; Stauss and Mang1999). Besides the highly general and stylizedcharacterisation of national groups that followedHofstede's seminal work, service managers havelittle to go on in designing and localizing theirservices. The globalisation of service productsand inherent intangibility and humaninteractivity that marks most services has sharplyraised the potential for service product failures.

There is, therefore, a growing interest inunderstanding the interaction between thenational and sub-national cultural influences andservice products. Concomitantly, there is anoticeable burst of research examining theculture-service nexus in regions other thanEurope and North America (Winstedt 1997;Stauss and Mang 1999). Traditionally, this meantthe need to understand the cultures of theEuropean and Asians.

Reflecting this need Anderson and Fornell(1994) in their 'consumer satisfaction researchprospectus' called for more systematic investigation

Hazman Shah Abdullah & Razmi Chik

into the variations in satisfaction across nations.Due to the interactive and intangible nature ofservices, cultural expectations play an importantrole in predisposing the customers towards theconsumption experience and their attention andreaction to cues in the service environment. Itstrongly influences the values that customers arelikely to assign to specific service attributes, theperception of the characteristics of the serviceproviders and the strength of their reaction tothe presence or absence of the attributes (Matilla1999).

Since their appeal, there have been severalstudies to examine the influence of culture oncustomer satisfaction (Winsted 1997; Donthuand Yoo 1998; Matilla 1999). Despite the obviousrole of culture in service quality, the understandingis still rather nascent. As services become moreglobal, there is need to develop betterunderstanding of the influence of differentcultures on different dimensions of servicequality.

The research thus far has exclusively focusedon national and ethnic groups/cultural groups.Because these groups are distinct and commonlybecome the basis of marketing decisions, theyare selected as the natural units of observation.While broad cultural categories still form thebasis of global market segmentation, the culturalstereotyping often conceal significant variationswithin groups that allow for finer segmentation(Matilla 1999). Yet, much of the culture andservice quality research relies on the most notablecultural denomination, the national culture.Additionally, the focus of culture-service qualityinteraction study has been on polar oppositecultures. The national cultural classifications anddistinctions conceal much of the distinct culturalsub-groups. These subgroups evince variations,which range from shades of the main culture tovastly different cultural preferences withinsupposedly homogenous cultures. As moreevidence of culture-service quality nexusbecomes available, the question is no longer ofthe connection between the two but rather theexpansion of research to even ostensiblymonocultural environments. There is need,therefore, to look for cultural variations withinsupposedly homogenous cultural groups.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Of particular interest within the service qualityresearch stream has been the interaction between

the service provider and the customer. Thedominant service quality model places thecustomer expectation as the subjective standardby which a customer evaluates the serviceperformance (Zeithaml, Parasuraman and Berry1993). Although the explanatory role of customerexpectations in service quality assessment hasbeen questioned, it still is accepted as providingvaluable means to judge performance assessmentsby the customer (Cronin and Taylor 1992). Theexpectation itself is a product of a complexnumber of factors. The values or culturalorientations of the customer are believed toprovide the broadest framework to understandexpectations. Consequently, a new stream ofresearch has begun to explore the role of culturein expectation formation and how differentcultural orientations impact their evaluation ofthe various elements in the service performance.Winsted (1997) succinctly brings out theconceptual link between service encounters andsocial encounters through the followingobservation;

"Because service encounters are social encounters,rules and expectations related to services encountersshould vary considerably according to culture, yetvery little guidance has been provided regardingthe influence of culture on perceptions of serviceprovision" (p.106).

Many writers have argued for the need forgoods and services to be adapted to the differentlocal cultures. Alden, Hoyer and Lee (1993)showed how the use of humour in advertisingmust be carefully vetted for offensive elementswhen applied cross-culturally. Generally, thecultural comparisons have been between culturesthat can be characterised as polar opposites likethe Japanese and the Americans. Winsted (1997)studied the influence of the cultural values onthe service quality expectations and evaluations.She found that the Americans expectedegalitarianism in service and higher degree ofpersonalisation while their Japanese counterpartpreferred more formality in treatment. Malhotra,Ugaldo, Agarwal and Baalbaki's (1994) study isamong the few studies on the cultural dimensionsof developing and developed countries and theireffect on the service quality dimensions. Theyfound that the value orientations as measuredvia Hofstede's 5 dimensional continua had asignificant bearing on the service qualityevaluations of the respondents. The findings

98 PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002

The Influence of Value on Service Quality Perceptions in a Mono-Cultural Context

point toward the need to localise in internationalmarketing. Donthu and Yoo (1998) examinedthe effect of cultural values captured viaHofstede's five dimensional scales and theSERQUAL dimensions of reliability, assurance,empathy, responsiveness and tangibles. On mostof the service quality dimensions there werestatistically significant differences in theirevaluations of the retail banking services.Although people processing services are positedas most susceptible to cultural effects (Furrer,Ben and Sudharshan 2000), Matilla (1999)explored the impact of culture on hedonicservices. The experience rich services permit thecultural nuances to play a greater role than inother forms of services. Accordingly, it wasreported that Western and Non-western businesstravelers responded to different service cues.Generally it was found that Asian travelers paidmore attention to non-tangible and nonverbalcues more that their western counterpart.However, the study also highlighted and alertedattention to the variations possible withinotherwise monolithic cultures. Stauss and Mang(1999) tested the hypothesis that inter-culturalservice encounters are more problematic thanintra-cultural encounters using critical incidentmethod. Interestingly, the results confirmed thereverse. Intra-cultural encounters were moreproblematic than the inter-cultural ones. Thestudy also used somewhat polar cultures in testingthis hypothesis.

Furrer et ai (2000) provide a recent study ofthe impact of culture on service quality. Theystudied the cultural orientations of American,Asian and European students. They developed acultural service quality index that captured theinteraction between the service qualitydimensions and the cultural dimensions. Theyshowed how the groups of students could besegmented on the basis of their culturalproclivities and the service quality dimensions ofvalue.

It is apparent that most of the above-mentioned studies have sought to explore theculture-service question using polar oppositescultures. The use of these 'maximally' differentcultures is understandable as they enhance thepower of the design to test the postulations. TheWestern vs. Non-Western or American vs. Non-American designs have shown that the culture-service effect is real and must be addressed byglobal service producers.

What is of significance is that thesepostulations can be more stringently tested ifthey are subjected to less extreme culturalvarieties. The exploration of the conceptuallyviable thesis of finer cultural variations and theireffect of services evaluations has been put forthby Matilla (1999) who observed that ".. .consumerexperiences do not remain stable across culturesbut instead are open to influences of specificcultures". Indeed, the study of this postulationwithin what is known as homogenous cultures,can open the same advantages to marketers ashas been suggested about inter-cultural studiesin international marketing. Niche marketing canimmensely benefit from the understanding ofthe differences in what is otherwise believed tobe mono-cultural societies, by exploiting theinteraction between specific cultural nuancesand the sensitivity to specific service dimensions.Where the service attributes can be easilymodified, the within culture value orientationscan be a basis to customise services for the nichemarkets.

Problem Statement

From the review of the literature, it is evidentthat there is a dire need for culture-servicestudies to examine the role of value orientationswithin a culturally homogenous context (Winsted1997; Matilla 1999). The focus on within culturevariations in values will add greater credence tothe culture-service studies and allow for finerdistinctions and their a t tendant serviceimplications. This study explores this new andpotentially fruitful focus question. The centralresearch question is whether there are distinctvalue orientations within a cultural group.

The Conceptual Framework

The relationship between the service and cultureemanates from the basic characteristic of servicesas intangible and interactive (Shostack 1977;Lovelock and Wright 2002). Because serviceencounters are essentially social exchanges, thevalues undoubtedly colour the perception ofboth parties. Though not directly apparent,values underpin the expectations, biases,preferences, self-confidence etc. of the customers.Though not directly observable, values have beenconceptualized along several key dimensions.One such framework is advanced by Hofstede(1980). Hofstede captured the 'collective

PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002 99

Hazman Shah Abdullah 8c Razmi Chik

» Power distance• Uncertaintly Avoidance• Masculinity-Feminity• Collectivism-individualism

Service QualityPerception

ResponsivenessReliabilityTangibleAssuranceEmpathy

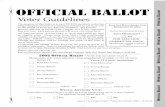

Fig. 1: Conceptual framework

programming of the mind' via four valuedimensions namely, Power Distance (PD),Uncertainty Avoidance, Masculinity-femininityand Collectivism-individualism (Fig, 1). Powerdistance refers to the acceptance of asymmetricalpower distributions by members of a group orcommunity. In high PD societies, hierarchy isaccepted and may even be revered. In servicecontexts, PD conditions the perceptions of thestatus of the service provider and the desiredbehaviour on the part of the customer.Masculinity-femininity relates to the extent towhich strong, aggressive and assertive behavioursare preferred or accepted or desired. Uncertaintyavoidance is the aversion to risks andunstructured behaviour situations. The clarity ofone's role is desired as opposed to self-development of the roles in any context. Finally,collectivism-individualism indicates the premiumplaced on self as opposed to the group, be it thesociety, community or the team. These fourdimensions are landmarks of value orientationof any group. The impact of the values onservices is eventually felt in the customers'assessment of the service quality itself. The valuesare expected to impact service quality throughthe customers' perceptions of the extent ofresponsiveness, reliability, empathy, assuranceand tangibles. These dimensions are susceptibleto the preferences and biases that the customerbrings into a service encounter. The values tendto affect the customer's position vis-a-vis theservice provider by creating mental zones ofcomfort and discomfort and culturallyappropriate roles and behaviours.

However, the interaction between the valuesand the services is not likely to be the same in alltypes of service encounter (Chase 1978; Lovelockand Wright 2002: 54). Some services involvehigh contact between the customer and the

service provider. In high contact services, theextended nature of the social exchange createsmore opportunity for values to affect servicequality perceptions. In low contact services, theinteraction may be short or even momentary.Consequently, the social expectations and valueorientations are unlikely to leave much impact.

Research Hypotheses

HI: There are significantly differing valueorientations.

H2: Value orientations correlate significantly withservice quality dimensions.

H3: The influence of value orientation on theservice quality perception is more evident inhigh contact rather than low contact services.

RESEARCH DESIGNA cross-sectional correlational study was carriedout involving 712 students of UiTM to determinethe influence of value orientation of Malayuniversity students on their service qualityexpectations and perceptions. The Malays haveexperienced dramatic socio-economic changesover the last two decades. This has introducedand amplified the cultural variations within theMalay community. The current concern aboutthe lack of unity among the Malays is arguablyengendered by greater variations in values andconsequently, different expectations andassessments. The Malay university students are aclose microcosm of the larger Malay society.Therefore, it offers a good setting to test theresearch question advanced in this study. Arepresentative, though not a random, sample ofthe student population was obtained for thisstudy from two of the 13 campuses of thisuniversity. The main campus represents an urbancentre while the East Coast campus captures amore rural background.

To examine the impact of value orientationon service quality expectations, 3 types ofuniversity services having different degrees ofcustomer contact were identified. These servicesrange from counseling (high contact) to medical(moderate contact) to library services (lowcontact) (Table 1). It is well established that notall services allow or require prolonged contactwith the customer/user. The influence of theuser's value orientation is most likely to mattera great deal in shaping his/her involvement andhis/her reaction to the behaviour of the service

100 PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002

The Influence of Value on Service Quality Perceptions in a Mono-Cultural Context

TABLE 1Distribution of the sample

Nature of Service Sample Size Sample Size(actual) (planned)

High ContactCounseling (S. Alam 8cTerengganu) 149 200

Moderate ContactMedical Care (S. Alam &Terengganu) 273 200

Low ContactLibrary Service (S.Alam8c Terengganu) 290 200

Total Sample 712 600

provider in high contact services. Conversely,the influence of value orientation of the studentis less likely to impact service quality where thecustomer and service provider contact ismomentary, limited and tangible. The three typesof services were used to detect the moderatingrole of contact in examining the influence ofvalues on service quality perceptions of thestudents.

Development of the Measurement InstrumentsAlthough the two constructs involved in thisstudy have been defined and measured in manyprevious studies, a conscious decision was madeto review this definition and the performance ofthese instruments. Hofstede's measures of valueswere work organisation based. Their relevanceand performance in the context of the servicesand the sector under study in this research arequestionable. Therefore, several items weregenerated for each of the five value dimensions.The item development followed the processsuggested by Dunn et al (1994). The items werereviewed by peers familiar with the subject asrecommended by Dunn et al. (1994). Twoacademics were required to link the items to thedimension the item appears to measure. Throughthis process the items that were not identified bythe peers as linked to a dimension were dropped.This process of substantive validation is stated byDunn et al. (1994) as the most crucial step inconstruct validation because substantiveconvergence should precede statisticalconvergence.

The value orientations were measured usingHofstede's 5 dimensional instrument (Hofstede1980,1991). These dimensions are Power-

Distance, Individualism-collectivism, UncertaintyAvoidance, Masculinity-femininity and TimeOrientation. Although this instrument wasdeveloped and used to measure the nationalvalues, it has been successfully used to studyculture at an individual level (Matilla 1999).

The original measures of value orientationdeveloped by Hofstede were specifically focussedon work-related values. Since this study addressesa university context, the original items weredeemed inappropriate. Based on the 5 key valueorientation dimensions, 28 items were generated.Only items that passed the substantive validationprocess were finally accepted for use in the pilottest. The pilot test based on a sample of 30individuals was collected and the CronbachAlphas were determined. The measure attainedthe minimum threshold of 0.7 (Nunnally 1978).In the study however, the reliability coefficientswere slightly below the recommended thresholdof .7. Collectivity, masculinity, uncertaintyavoidance and power distance achieved aCronbach alpha of 0.66, 0.60, 0.63, and 0.60respectively. Since the Cronbach alphas wereonly marginally lower than the threshold andthe lower Cronbach alphas have been used inorganisational studies, we did not think that thiswould seriously affect the outcome.

The service quality perception was measuredusing the SERQUAL dimensions (Parasuramanet al. 1988). This instrument has five servicequality dimensions namely; tangibles,responsiveness, reliability, assurance andempathy. Parasuraman et al. (1989) viewed servicequality as the difference between the perceptionand the expectation. As Cronin and Taylor(1992) pointed out, the measure of perceptionitself is sufficient measure of the service withoutthe weighting by expectation attached by theclients. Because Cronin and Taylor's approachyields a simpler measure, we have adopted it forthis study. Just like Hofstede's measures, theSERQUAL items are generic items that may beinappropriate for the present educationalcontext. Therefore, the items were developedreflecting the dimensions and put through thesame substantive validation process as in thecase of value orientation measures. The itemswere measured on a 7-point Likert scale with 1denoting Strongly Disagree. All measures attaineda minimum Cronbach Alpha of .60 in the mainsurvey, slightly less than the values obtainedduring the piloting stage. Though the reliability

Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. 8c Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002 101

Hazman Shah Abdullah & Razmi Chik

coefficients were lower than Nunnally's .70, lowerreliabilities have been used in published studies(Hinkin 1995).

Data Collection and Data AnalysisData were collected from two campuses namely,the Shah Alam and the Terengganu campuses.Trained enumerators were positioned at theservice centres to identify and sample therespondents (based on the quota samplingmethod) as they left the service centre after aservice encounter. This method allowed foraccurate recollection of the experience than at alatter time. They were asked to complete aquestionnaire containing the instruments. Inthe case of the counseling service, the counselorsprovided the questionnaires to the respondentswhen the students came in for consultation.This deviation was unavoidable because of theunplanned and irregular nature of the serviceneed. Basic descriptive statistics was used toexplore the distributional and locationalcharacteristics of the variables and determinethe appropriateness of the statistical techniquesgiven the descriptive properties. Unlike otherstudies that have used demographic factors toexamine the existence and the influence ofvalue orientations on variables of interest, thisstudy follows a method suggested by Furrer et ai(2000). Value orientations are composed ofunique combinations of the value dimensions.Demographic, ethnic and other common a prioriclassifications may not necessarily correlate withvalue orientations. As such, using any one ofthese a priori groups may result in erroneousfindings. Therefore, Furrer etal (2000) suggestedthat the value groups must be empirically derivedthrough the use of grouping techniques likecluster analysis. Accordingly, cluster analysis wascarried out to examine the cluster properties ofthe respondents. Subsequent analyses of variance(ANOVA) used the value clusters (Traditionalistsand Transitory Traditionalists) to examine therelationship between the value clusters andservice quality dimensions.

Profile of the Respondents

There is a greater representation of studentsfrom the Terengganu campus than from theShah Alam campus in the sample. This reflectsmore the accessibility to respondents and theintensity of use of the selected services thananything else.

There is two to one ratio of female to malestudents. This skewed distribution is reflective ofthe overall student composition in UniversitiTeknologi MARA. From Table 2 it is clear thatthe respondents are preponderantly Diplomaholders. This reflects the general distribution ofstudents and also because these students aregiven priority for campus housing. They,therefore, are in campuses and presumably, alsouse the services more than others who areaccorded the same privileges.

In keeping with the university's socialcommitment, the bulk of the respondents fallunder the category of the lower income group.The distribution is also influenced by the greatershare of the Terengganu campus in the totalsample, which attracts students from the EastCoast which is a lower income region in Malaysia.The distribution of the sample is weighted slightlyin favour of the library services. This is, asexplained in the methods section, an outcomeof the nature of the use of the library services.Library services are more intensively used ascompared with medical and counseling services.The former are dictated by the nature of thecampus activity while the latter are peripheralservices.

FINDINGSIntra-Cultural Variations

The correlation matrix in Table 3 displays thespecific dynamics of the culture-service qualityrelationships. All correlation coefficients > .10are significant. The 4 dimensions of the culturalorientations are not strongly correlated,indicating that the dimensions are distinct andnot overlapping ones. The highest correlation isbetween uncertainty avoidance and collectiveorientation (.410). The correlation between theservice quality dimensions and culturaldimensions is of particular interest. Powerdistance is significantly correlated with all servicequality dimensions except responsiveness.However, the correlation values are small or low.This suggests that while the relationship issignificant, the impact of this orientation onservice quality is quite limited at best. Thecorrelation between the service quality and thecultural orientation dimensions is low. This is tobe expected given that this study is focussed onexamining relationship between thesedimensions within a mono-cultural context.Uncertainty avoidance also displays similar

102 PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. 8c Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002

The Influence of Value on Service Quality Perceptions in a Mono-Cultural Context

TABLE 2Profile of respondents

No.

CampusShah AlamTerengganu

GenderMaleFemale

ProgrammeDegreeDiplomaCertificateOthers

Parents Income*<500501-10001001 -15001501 -20002001 - 25002501 - 30003001 - 35003501 - 4000>4000

Type of ServiceCounselingMedicalLibrary

* n = 622

297415

234478

246449

98

16722415563329272447

149273290

4258

3367

356311

27362955448

213841

TABLE 3Correlation between the service quality and culture variables

No Variables 1 4

123456789

EmpathyAssuranceResponsivenessTangibleReliablePower DistanceUncertainty AvoidanceMasculinity-FemininityCollectivism-Individualism

.585**

.696**

.608**

.530**

.106**

.121**.043

.217**

.529**

.523**

.465**

.108**

.187**.088*

.252**

.602**

.581**.030.076*-.051

.183**

.566**

.182**

.174**.061

.282**

.172**

.249**

.107**

.265**

.197**

.187**

.132**.295**.410** .285**

p<.005, **p<.001 (2-tailed test).

correlation with all service quality dimensionsbut appears to be relatively more correlated withReliability. Masculinity is least significantlycorrelated with the value orientations.

The value orientations of the students weremeasured via 5 dimensional continua providedby Hofstede (1990) but time orientation itemsfailed to show satisfactory convergence andtherefore, have been excluded from further

analysis. It has been argued that since culturalvalues condition the mind and behaviour in acollective fashion, it should be combined tocreate recognisable value groups for analysis(Furrer et al. 2000). Consequently, it is imperativethat the value orientations are understood as abundle or cluster rather than individual variables.Following in the footsteps of Furrer et al (2000),

PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. 8c Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002 103

Hazman Shah Abdullah 8c Razmi Chik

the data was cluster analysed to detect groupsthat have distinctive combinations of the 4 valuedimensions. Cluster analysis generated twodistinct groups. We have labeled the clusters asTrue Traditionalist (cluster 1) and TransitoryTraditionalist (cluster 2).

The value orientations were measured on a7-point scale with 1 denoting low and 7 high.Cluster 1, the True Traditionalists display agreater proclivity to the collective interest,appears to accept the appropriacy of greaterassertiveness, greater power distance in generalrelationship and greater aversion to uncertainty.Typical Malay society places a very high premiumon collective rather than individualistic interest,the culture can only be classified as feminine innature with its emphasis on gentleness, decorumand politeness in social encounters and even indisagreement, accepting and also veneratingpower distance and preferring to avoiduncertainty. The Transitory Traditionalists(cluster 2) scored lower on all dimensions of the

value orientations but in case of Masculinity, it isonly marginally lower than their TrueTraditionalists peers. The Transitory Traditionalistsare a group experiencing some dilution of thecultural values that typify the Malay communityat large. Based on the evidence from Table 4, wecan conclude that there are distinctly differinggroups within the Malay student community.Therefore, the 1st hypothesis that there aredistinct sub-cultural groups within presumablyhomogenous groups is supported.

Table 5 provides some answers to thequestion whether there is significant relationshipbetween the value clusters and the perceptionsof service quality. The one-way ANOVA showsthat the service quality dimensions differsignificantly between the 2 value clusters. Thisthen provides the support for the hypothesisthat value orientations influence or have someimpact on service quality perceptions. Thus, thesecond hypothesis is also supported.

TABLE 4Value clusters

Value Orientations Clusters

True TransitoryTraditionalists Traditionalist

(Means) (Means)

CollectivityMasculinityPower DistanceUncertainty Avoidance

6.14 (high)4.69(med)4.18(med)5.58(high)

4.72 (med)3.99(med)3.90(med)4.69(med)

N 417 295

TABLE 5Influence of cultural clusters on service quality

Service QualityDimensions

Empathy

Assurance

Responsiveness

Tangible

Reliable

ValueClusters

Between groupsWithin group

Between groupsWithin group

Between groupsWithin group

Between groupsWithin group

Between groupsWithin group

Sum ofSq.

33.596925.860

13.076407.631

18.063763.768

37.252742.772

42.572724.217

df

1710

1710

1710

1710

1710

MeanSq

33.5961.304

13.076.574

18.0631.076

37.2521.046

42.5721.020

&g

.000

.000

.000

.000

.000

104 Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. & Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002

The Influence of Value on Service Quality Perceptions in a Mono-Cultural Context

The last hypothesis advanced was whetherthe postulated relationship between valueorientation and service quality differs given thetype of service involved. Multivariate analysis ofvariance showed that that there are nointeractions between service type and valueorientations. Therefore, the last hypothesis thatthe relationship between value orientation andservice quality will be more distinct in highcontact service was not supported.

In summary, the findings of this studysupport two of the three hypotheses advanced.Significant variations in values can be observedeven within such homogenous groups as Malayuniversity students. These variations are notwithout influence on the service qualitydimensions.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONFrom a theoretical standpoint, this study expandson the current culture-service quality researchby seeking out finer distinctions and how theymay be pertinent to service providers. Pastresearches tended to use cultural extremes orpolar opposites to show the effect of culture ofservice perceptions (Furrer et al 2000; Winsted1997; Matilla 1999). While this is an admirableapproach and design, the design is intended toshow the postulated relationship. In fact, it couldbe argued that the design is too powerful andtherefore, the outcome is almost a certainty.This study by examining the same issue in anintra-cultural setting is actually putting thepostulation to a much more stringent test thanhas been the case thus far. By seeking out therelationship between service quality and valueorientations intra-culturally, the hypothesis is putto a more stringent test.

The study also provides some evidence ofthe existence of a spectrum of value orientations(though the range is limited) within an ostensiblyhomogenous group. Although polar oppositecultures dominate culture-service studies, valueorientations within homogenous cultures areequally valid and fruitful areas of scrutiny(Winsted 1997). This study established that therewere two cultural clusters. These groups, labeledas Transitory Traditionalists and TrueTraditionalists, provide a significantly differentvalue profile. While both groups display Malaycultural proclivities, the Transitory Traditionalistsis markedly less respectful of old values. Theuniversities have become grounds to question

the wisdom of the old ways. The value profileshowed here reflects the changing socio-psychological landscape within the universitystudent population and to some extent, withinthe society at large. The lack of strongly distinctvalue orientations among the groups is more afunction of the homogeneity of the sample thananything else. If a more heterogeneous samplehad been acquired, the value profile would havevaried much more than observed in this study.

From a managerial standpoint, the serviceproviders in the public sphere, especially thepublic tertiary institutions must be more awareof the value orientations and how they impactthe many quality initiatives that are currentlyinstituted (Cheong 2000). Students still haveand are therefore, likely to display values thatplace a high premium on collective interests.Therefore, services that explicitly or implicitlyrequire one to show individualistic tendenciesmay cause significant discomfort or dissonance.Students are likely to feel at ease when doingthings together and for the benefit of all ratherthan self only. Relatively high tolerance for powerdistance is expected to manifest itself in ratherpassive, meek and unassertive behaviour. Thisdisposition will prevent effective feedback fromthe service users. Users are likely to be verycognizant of the structure, hierarchy, order andauthority and thus less inclined to question orcomplaint or provide feedback which is notanonymous. Quite unexpectedly, the respondentshave expressed a more masculine interest. Thisproclivity for assertive behaviour does not quitefit with the other orientations especially powerdistance and collective interest. Given that theMalay community is in the midst of intense andoften acrimonious changes socially and culturally,conflicting behaviour especially among theimpressionable population may account for thecontradiction (Mastor, Jin and Cooper 2000).Making services changes without understandingthe cultural nuances of the users will result insupplier-orientated changes. The interactionbetween the value orientations and service qualitydimensions allows for changes that are alignedwith the cultural preferences of the students.Many service innovations have strong implicitvalue base. Most, if not all innovations wereborn in Caucasian cultures. The effectiveness ofthese innovations is implicitly a product of thevalue orientations of the co-producers orco-creators - the service recipients. Changes that

PertanikaJ. Soc. Sci. 8c Hum. Vol. 10 No. 2 2002 105

Hazman Shah Abdullah & Razmi Chik

embody greater egalitarianism or empowermentmay actually have the effect of inconveniencingthe service users because of their value system.The total quality management initiatives willonly be effective if the user values are capturedand used to bring about service innovation.

As is customary, some caveats are in order.The measures did not display a high level ofreliability as was expected. Improvements andfurther purification of the measures will enhancethe strength the correlations and the clarity ofthe nomological network. The use of a fairlyhomogenous sample (Malay university students)probably did restrict the range of valueorientations. Perhaps, a more representative mixof the members of the Malay community willdisplay even greater variation in valueorientations than is the case here. Future studiesshould examine the interactions between valueorientations and the service quality dimensionsin specific service sectors to reveal profitablepossibilities in service adaptation.

In summary, the study has shown that thereis risk in stereotyping the cultural traits of Non-Western societies and in this particular case, theMalays. There exist significant value variationswithin ethnic and sub-cultural groups.Recognising this will open up new possibilitiesfor service adaptations, which is necessary tocompete in the highly competitive market placeas well as the non-competitive public sector. Aswe move beyond the first round of TQMinitiatives, finer distinctions will become a centerof focus in further service improvements andadaptations.

REFERENCESALDEN, D. L., W. D. HOYER and C. LEE. 1993.

Identifying global and culture specificdimensions of humor in advertising: Amultinational analysis. Journal of Marketing 57April: 64-75.

ANDERSON, E. W. and C. FORNELL. 1994. A customersatisfaction research prospectus. In ServiceQuality: New Directions in Theory and Practice, ed.Roland T. Rust and Richard L. Oliver, p. 241-268. CA Sage: Thousand Oaks.

CHASE, R. C. 1978. Where does the customer fit ina service operation? Harvard Business ReviewNov-Dec: 137-142.

CHEONG, C. Y. 2000. Cultural factors in educationaleffectiveness: A framework for comparative

research. School Leadership and Management20(2): 207-225.

CRONIN, J. J. and S. A. TAYLOR. 1992. Measuringservice quality: A reexamination and extension.Journal of Marketing Research 3: 55-68.

DONTHU, N. and B. Yoo. 1998. Cultural influenceson service quality expectation. Journal of ServiceResearch 1(2): 178-186.

DUNN, S. C, R. F. SEAKER and M. A. WALLER. 1994.

Latent variables in business logistics research:Scale development and validation. Journal ofBusiness Logistics 15(2): 145-172.

FURRER, O., B. S. C. Liu and D. SUDARSHAN. 2000.The relationships between culture and servicequality perceptions. Journal of Service Research2(4): 355-371.

GRONROOS. 1993. Services Management and Marketing.Singapore: Maxwell Macmillan.

GuMMESsoN, E. 1991. Marketing Organisations inservice businesses: The role of part-timemarketers. In Managing and Marketing Servicesin the 1990% ed. Teare, R., L. Muotinho andN. Morgan, Cassel, p. 35-48.