Javier Caballero - uv.mx

Transcript of Javier Caballero - uv.mx

ITN oleo LÓGI CA. VOL I, N.. 1, 1992

Javier Caballero

~ Homegardens, household gardensl ~ or kitchen gardens, are a traditionalagricultural system widespread in most of thetropical regions of the world. They are as theareas surrounding the house which are plantedwith a mixture of many plant species, mainlyfruit trees and root crops (Soemarwoto, 1981).These agroecosystems have great importancefor subsistence among indigenous people as hasbeen shown from a number of studies carriedout in Asia, Mexico and Central America (Ab-doeh1lah and Henky, 1979; Anderson, 1952;Anderson, 1979, 1986; Basurto, 1982; Brierly,1976; Diarra, 1975; Kimber, 1966, 1978; Lazoset al., 1989; Vara, 1980 among others). The abo-ve studies have shown that homegardens provi-de a criticai complement for human nutrition,health and many other human needs. Home-gardens may also represent a source of incomefor cultivators.

The diversity and complexity of homegar-dens cultivated by the modem Maya of theYucatan Peninsula, Mexico, are overwhelming.They probably constitute one of the most soph-isticated examples of this kind of agroeco-system in the world. Several studies presentingpartial descriptions or analyzing specific aspectsof the structure and composition of Mayahomegardens have been published during the

:a5u¡.¡o.>~3.o

Javier Caballero: Jardín Botánico. Universidad Nacional

Autónoma de México. Apartado Postal 7~14. D.F. 04510,

México

35

.lAVIIR CABALLIRO ~

last few years (Smith and Cameron, 1977; Bar-rera et al., 1980; Vara, 1980; Vargas, 1983;Sanabria, 1986; Rico-Gray et al., 1990, 1991;Caballero 1991). This study presents a generaldescription of modern Maya homegardens anddiscusses their origin as well as perspectives fortheir future development.

Methods

Data presented were obtained as a part of anethnobotanical inventory conducted between1984and 1991 throughout the Maya area oftheYucatan peninsula. This inventory includedboth the collection of plant voucher specimensand open interviews with Maya householdersand local market vendors. A systematicsampling of the trees and shrubs grown in 60homegardens from 10 towns and vi"ages fromdifferent regions of the Yucatan Peninsula wasalso conducted in 1985. Measures of height andbasal area of each plant individual as we" as therelative abundance of each plant species wereobtained for each one of the 60 homegardenssampled. Voucher specimens numbered underthe author's co"ections were deposited at theHerbario Nacional and at the ethnobotanicalco"ection of the Jardín Botánico both of theUniversidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

The Study Area

The Yucatan Peninsula is a low, flat limestoneplatform. The absence of significant elevationas well as the uniformity of the substratum en-tails a relatively homogeneus ecology which isaltered only by the existence of increasing dry-ness from the Southwest to the Northwest(Miranda, 1958). In correspondence to thiscline of increasing dryness, the natural vegeta-

36

~

ITNOICOLÓGICA. VOL I, N.. I, 1992

,:;::::¡-

~

---

DZONOT

vO~

",'<i

~

.f

(>o

o .o 100...

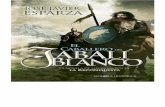

Figure I. Location of the ten villages where the floristicsampling of 60 homegardens was conducted.

where slash and burn agriculture is still themain economic activity .

tion of the Yucatan peninsula ranges fromtropical evergreen forest in the southern regionof the peninsula, and subdecidous forest in thecentral and northeastern peninsula todeciduous forest in the northwestem penin-sula (Miranda, 1958; Rico-Gray et al., 1988 ).These climatic and vegetational differences donot seem to affect the distribution of the plantscultivated by the Maya, including those speciesgrown in the homegardens.

The modem Maya are located in the north-ern third of the Peninsula, in the state ofYucatan, the northern part of Campeche, aswel1 as in the central part of the state of Quin-tana Roo. Despite some minor differences incultural traits such as dress and language, thepresent Maya area can be considered as cul-tural1y homogeneous. Significant differencesamong Maya populations are related more tothe degree o( its integration into the nationalcultural mainstream.

Although the practice of traditional produc-tive activities such as the cultivation of milpasand homegardens is stil1 widespread all over themodern Maya area, a significant degree ofeconomic specialization exists in different partsof the Yucatan Peninsula. According to this, the10 towns and villages where I sampledhomegardens are representative of four dif-ferent economic regions of the modem Mayaarea in the Yucatan Peninsula (Figure 1 ). Locheand Dzonot Ake are vil1ages in the cattle raisingregion of northeastern Yucatan. Maxcanu andTicul are towns representative of easternYucatan where different economic activities arecombined such as growing fruit trees, plantingsisal (Agave spp) and making palm handicrafts.Pomuch and Tenabo in northem Campecheare vil1ages where the population combinesmaize and fruit tree cultivation with henequén(Sisal) agriculture, as wel1 as other minor ac-tivities. The vil1ages of Chan Kom, Huayma,Ichmul and Xkom-Ha represent the more tradi-tional areas of Yucatan and Quintana Roo

The Modem Maya Homegardens

The Maya homegarden is ca"ed locally huerloor solar, however the last term refers moreprecisely to the homegarden as a social space.According to Thompson (1974), the solar is thebasic Maya residential unit which demarcatesthe functioning domestic group, whether this isa nuclear or an extended family. Thus the solaris not simply the domicile of families but theplace where the families dwell and the spatiallocus of the social processes which involve thedomestic group such as grow and fission offamilies over time.

SPatial Organization

Maya hornegardens are cornrnonly rectangularalthough sornetirnes they can be square and

37

JAYlER CABALLERO ¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿

cultivate chile (Capsicum anuum), and other con-diments in pots or in wooden raised beds calledca'anche. The second section is the larger oneand usually occupies more than 80% of thetotal area of the homegarden. This section isdevoted to growing perennial plants basicallytrees and some shrubs. A third section calledlocally pach pakal is devoted to the cultivationof annual crops mainly vegetables, beans andmaize. The fourth section is usually located atthe front of the house and is devoted to thecultivation of a great variety of ornamentalplants. This is the smallest part of a homegar-den and often is reduced to a only few in-dividuals planted in pots. As described by Rico-Gray et al. (1990) it is common to find a fifthsection of the homegarden which is not a cul-tivated area. This section is occupied by naturalvegetation mainly secondary forests which con-tains both usefuJ and non-useful wild plants. Ac-

they rarely have an irregular shape. They arecontained by a low mortarless stone wall. Asreported for the villages of Tixpehual and Tix-cacaltuyub by Rico-Gray et al. (1990), the size ofthe Maya homegardens vary greatly as a resultof a long and complicated process of allocationand subsequent division of land. From thesample of 60 homegardens, I estimated that thetraditional Maya homegarden usually has anarea between 600 and 2 000m2 but sometimesthis area can be up to 5 000m2. Rico-Gray et al.(1990) reported a mean of 2 500m2, with amaximum of 5 000m2 and a minimum of400m2 for a sample of 42 homegardens of Tix-pehual and Tixcacaltuyub.

Although not clearly defined, four differentsections form the traditional Maya homegarden(Figure 2). The first section contains the house,the kitchen and an open area devoted to raisingpigs and poultry. In this area people commonly

Secono8ry

(I

~.

:~!.~

~

~.~ .~

"'\

.

,,' .-c

~.:. .:.:;\\'.. ..

..~~:~~ ..:.::-:.w.

. -..:. . . .

, ,. '. ...cRche

-o;.

:- h~nhous~..

D~ ~

~.:.~ :*~-.~ ~

~ ., .~ k .\ :c--" \: ...~. ~ 1t.cll~n =-==::::::;¡ . ~. ...r-", ..,. -"' , ,~, ~~ . ..-" J :.::-:. ,

, , .~ .. . ..hous~ .:.:., ., ...~ ,~. ~ ~ .(.- L :..

c :~~. ...::-:.:. ...p8ch p8k8 L ..' .:.:: .:.:.: .:.:.: .:.:.: .:.:.: oyna~n1:~ L

Figure 2. Idealized representation of the Maya homegarden spatial composition.

38

h~n1"1ous~

."., D.~.~.

nNOICOLÓGlCA. VOL I, N.. 1, 1992

~

cording to Sánchez (1991), this section con-stitutes along with the natural vegetation andthe milPa, the source of firewood for thehousehold.

The sections for produce and ornamentalplant cultivation as well as the secondary forestsection may be absent in any homegarden butnot the tree crop section. This section alongwith the residential area can be considered asthe defining elements of the typical modern

Maya homegarden.

Homegarden Structure

Maya homegardens, parcicularly the tree cropsection, have a complex structure and accord-ing to some authors (Barrera et al., 1980), theyresemble the structure of the nearby tropicalrain forest. In the vercical dimension a clear cutstracificacion does not exist, however in general,it is possible to recognize three different strata:a lower stratum of up to 2 meters height whichis formed by shrubs, small trees and other lifeforms; a middle stratum between 2 and 5meters; and a higher stratum between 5 and 15meters formed by the tallest trees (Figure 3).

The horizontal ordering of the plant in-dividuals in the homegardens was not systemati-cal1y recorded, however on the basis of fieldobservacions and the report by Rico-Gray et al.(1990), it can be said that no specific patternexists as earlier suggested by Barrera (1980).Interviews conducted by the author withhouseholders during the sampling of 60homegardens, indicated that the only criteriapeople fol1ow when plancing and managing thehomegarden is to avoid compecicion for lightbetween individuals. Thus people plant in-dividual trees in such a way that their crownsdo not overlapp and that lower trees are notovershadowed by tal1er ones. According to Bar-rera (1980), the ordering of plant individuals

Figure 3. Projection of 60 homegardens in a space of cha-racters (presence of species and varieties). as obtained froma Multidimensional Scaling. The final stress va1ue achievedwas 0.48. Numbers are homegardens: 1-6 Loche; 7-12 Dzo-not Ake; 13-18 Huayrna; 19-24 Chan Kom; 25-30 Xkom Ha;31-36 Ichmul; 37-42 Ticul; 43-48; Maxcanu; 49-54 Tenabo;55-60 Pomuch. Source: Caballero (1991).

in a homegarden is a function of many dif-ferent factors such as variation in soil type, dif-ferences in humidity, as well as the existinglight conditions.

Homegarden Flora

Maya homegardens are highly diverse. Fromthe sampling of 60 homegardens, I recorded atotal of 83 species and land races of trees andshrubs which are grown in the tree crop section(Appendix 1.). The number of species presentin the Maya homegardens may be significantly

.6..6..6.

39

JAVIER CABALLERO

~

higher if the plants from the other sections areincluded. Barrera (1980) reported 92 plantspeciés including trees, shn1bs and herbs, someof which are grown in the section of ornamen-tal plants. Vara (1980) recorded 133 speciesand land races from the homegardens of Yax-caba, Yucatan, including ornamental plants andannual crops cultivated in the pach pakal. In arecent study, Rico-Gray et al (1990, 1991)registered a toial of 187 species of trees andshrubs including the wild plants from the un-cultivated section as we" as the species growingin the ornamental plant section of thehomegardens of Tixpehual and Tixcacaltuyub.

The number of plant species and individualsfound in a single homegarden varies significant-Iy. The total number of individuals for both

trees and shrubs per homegarden, ranged be-tween 20 and 170 as recorded from the sampleof 60 homegardens. This variable numberseems to depend on a series of interrelated fac-tors such as the total area available, the age ofthe homegarden and the density of plantingchosen by the householder. As observed fromthe sample of 60 homegardens, older andlarger homegardens often have a larger num-ber of individuals, although according toevidence presented by Rico-Gray et al. (1990), itappears that the number of species planted aswell as the density of planting is not directlyrelated to the size and the age of the homegar-den but is largely a function of the particularpreferences of the householder .

Origin of the Homegarden Flora

The flora of the modern Maya homegardensresults from the combination of two basic ele-ments: plants native to the neotropics and;plants native to the old world (Table I) .Theneotropical plants can be further divided intothose species native to the Yucatan Peninsulaand those species native to other parts ofMexico and the neotropics.

Most of the plant species of the Mayahomegardens which are native to the Yucatanpeninsula are wild plants. They comprised 32%(26) of the species recorded from the sample of60 homegardens. These plants are mainly ta11trees, which are common elements in either theprimary and the secondary forests. They areleft to stand when the forest is cut down forestablishing a new homegarden. These plantscan also grow spontaneously from seeds andother propagules either already present in thehomegarden or natura"y dispersed in thehomegarden from the nearby forest or theneighboring homegardens. Once established,these plants are tolerated, protected and even

40

~

nNOICOLÓGlCA, VOL I, N.. " 1992

Table 1. Plant species and varieties most frequently found in a sample of 60 Maya homegardens of theYucatan Peninsula. Frequency values indicate that for example, Annono squomoso wos found in 65% ofthe homegardens (39 out of 60).

ORIGIN SPECIESPERCENT

LOCAL NAME FREQUENCY

Nativetothe

Neotropics

65.0%58.358.358.353.351.746.745.040.038.335.035.031.730.028.326.725.023.323.321.721.718.318.316.713.313.313.311.711.710.010.010.0

Annona squamosaBross;mum al;castrumMe/;ccocus b;iugatus

Spond;as purpureaT al;s;a o/;vaeform;s

Spond;as purpureaAnnona purpureaCedre/1a mex;canaEhret;a t;n;fo/;aCord;a dodecandraB;xa ore/lanaMan;lkara achrasCar;ca papayaSpond;as aff. momb;n

Spond;as purpureaPersea amer;canaSabal mex;cana

SabalyapaSpondias purpureaCn;doscolus chayamansaPs;d;um guaiavaByrson;ma crass;fo/;aCrescent;a cuieteP;sc;d;a p;sc;pulaBursera s;marubaChrysophy/1um ca;n;toP'umer;a a'baParment;era acu/eataJacarat;a mex;cana

Spond;as purpureaS. purpureaS. purpurea

ts'almuyooxhuaya cubanatuxpana abal

wayamchi abalkan opk'ui che'bek

k'oopte'k'uxub

chakya'chichtuxilo abalcampeche abalonbon xa'aniulok xa'ankan abal

chaaypichi'

nanche'luchhabimchakacaimito moradoflor de mayokatkumcheabal moradoabal sabakabal San Juan

NaliveloIheOldWorld

Citrus aurantium

C. sinensis

Citrus aurantifolia

Citrus reticulata

Citrus limetoides

Taindus indica

Musa (MB)

Mangifera indica

Cocus nucifera

Murraya paniculataMusa (MB)

Citrus aurantium

Citrus paradisi

78.373.358.333.331.726.725.021.720.020.015.013.313.3

naranja agriachina

limon agriomandarinalima

paj ch'ujukplatono dulce

mangococolimonoriaplata no macho

naranja xcajeratoronja

41

~

JAVIER CABALLERO

Table 3. Species of the modern Maya home-gardens which were economically important inprehispanic times and in the early Spanish co-lonial period. 8ased on Marcus (1982) andMiksicek (1983).

SPECIES PREHISPANICTIME

XVI-XVII

CENTURY

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Acrocom;o mex;cono

Agove s;so/ono

Annono cher;mo/o

A. purpureo

A. ret;cu/oto

A. squomoso

B;xo orellono

Bros;mum o/;costrum x

Byrson;mo cross;fol;o

Cor;co popoyo x

Cedrello mex;conoCn;doscolus choyomonso x

Cord;o dodecondro x

Crescent;o cuiete x

Ehret;o t;n;fol;o

Guozumo ulm;fol;o

Jocorot;o mex;cono

Lonchocorpus yucotonens;sMon;lkoro ochros x

Porment;ero spp.

Perseo omer;cono x

Pouter;o sopoto

Ps;d;um guoiovo

Sobo/spp. x

Spond;os spp x

T o/;s;o ol;voeform;s x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

the naranja agria ( CitTl1.5 aurantium) and thenaranja xcajera ( CitTl1.5-aurantium ) growing inthe Maya homegardens introduced early by theSpaniards and no longer cultivated in other re-gions of Mesoamerica. The persistence of thesecultivars in Yucatan seems to be a result of aseries of cultural and historical events such asthe early incorporation of these plants into thetraditional Maya diet and cuisine, as well as theprolonged cultural and economic isolation of

promoted by the householders. These plantsare the ones which dominate the canopy of thehomeg-ardens. Some of the more common wildspecies are Brosimum alicastrum, Sabal spp,Cedrella mexicana and the wild forms ofManilkara achras.

According to Barrera (1980) Cnidoscolus cha-yamansa is a homeg-arden plant species whichwas domesticated in the Yucatan Peninsula. The-re are also some cultivars of fruit trees such asthe %apote campechano (Manilkara achras) whichwere probably developed by the Maya from thewild forms. These cultivars as we" as the wildforms, most of which are sti" found in the natu-ral forests of the Peninsula, are utilized by thelocal population although the cultivated formsare often preferred over the wild ones.

The plants from the neotropics includespecies domesticated in different parts ofMesoamerica, the Caribbean, and SouthAmerica. Some of these species are sti" presentin the wild in those regions. These plants in-clude some of the more common elements inthe medium and lower strata of the homegar-dens, sucli as Annona reticulata, Melicoccusbijugata, Talisia olivaeformis, Bixa orellana, anddifferent cultivars of Spondias puryurea, (Table3). Some species such as Persea americana andseveral cultivars of Manilkara achras are alsocommon in the higher arboreal stratum.Species from the Caribbean and South Americainclude plants introduced to the Yucatanduring both prehispanic and colonial times.Historical sources such as the RelacionesGeográficas of the XVI century ( de la Garza,1983) and the Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán byDiego de Landa (Tozzer, 1941) suggest the in-troduction of species such as Bixa orellana sinceprehispanic times.

Plants from the old world are basica"y citrics,bananas and other fruits. They are dominantelements in the medium arboreal stratum of thehomeg-ardens (Table 3). It is common to find oldvarieties and cultivars of these species such as

.6..6..6.

42

¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿¿ ITNOICOLÓGICA, VOL I, N.. 1, 1992

the Yucatan Peninsula which has secured theendurance of the Maya culture.

Origin and Evolution of the Maya

Homegardens

Homegardens and SubsistencePrehispanic Roots of the Modern Homegardens

Despite the economic differences between thevarious regions of the Yucatan, the homegar-den plays an important role in household sub-sistence in all regions. The present Maya subsis-tence patterns, particularly those in the maizegrowing areas of Yucatan and Quintana Roo,are based on the traditional combination of adiversity of agricultural systems. These are theslash and burn cultivation or müpa, theproduce cultivation or pach pakal, and thehomegarden tree culture. Although staplefoods such as maize and beans are obtainedfrom slash and burn agriculture they are com-plemented with products from the pach pakaland the homegarden. Thus each agriculturalsystem along with other productive activitiessuch as bee keeping, provide different kinds offoods which are combined throughout the yearto satisfy the requirements of the human diet.They also represent a source of cash income.

As can be seen from Table 2, the plants gro-wing in homegardens are used for a variety ofpurposes such as medicinal and ceremonial uses,house thatching, as well as making tools andhousehold utensils. Nevertheless most of thespecies are food plants, mainly fuits, as can beseen from Table 2. More than 50% of the speciesreported from the sample of 60 homegardensare fruit trees. In nutritional terms this varietyof fruits represent an important source of vita-mins and minerals which supplement other nu-trients obtained from staple foods. In economicterms, homegardens products, particularlyfruits, are a source of cash income. As discussedby Rico-Gray et al., 1991, selling fruits from thehomegarden either in local or regional marketsas well as trading them locally in the villages isan important economic activity .

Although modem Maya homegardens can notbe considered as a prehispanic agricultural sys-tem, they seem to have evolved from someprehispanic tree culture system. As shown bythe numerous species from the old world whichare cultivated in the present homegardens,these agroecosystems are largely a result of thetechnological innovations introduced toMesoamerica by the Spaniards. On the other

Table 2. Uses af fhe species and variefiesgrawn in fhe free crap secfions of a sample of60 Maya homegardens.

NUMBEROF SPECIESUSE

46

8

6

6

5

4

4

4

fruit

medicinal

flavoringwood

ornament

vegetable

household utensils

ritual

seed

emergency food

fodder

handicrafts

colorant

tatching

ropes

tools

others

2

2

1

43

~

IAVIER CABALLERO

other hand, domesticated species such as Spon-dias spp., Persea ~ana, and Annona spp.could hardly have been cropped in the wild.They must have formed part of a system of treeculture which perhaps resembled the modernsystem of homegardens.

Most of the fruit trees cultivated in themodern homegardens have a broad range ofgenetic variability which appears to be a resultof a long process of manipulation by the Maya.In the case of Spondias pU1jJurea a total of 1 idifferent cultivars were recorded in this study.Although some cultivars such as tuxpana abalcould have been introduced to Yucatan (Bar-rera, 1980), most of them are not found inother regions of Mesoamerica. They seem tohave originated in the Maya area. The develop-ment of such genetic variability involves a longand complicated process of selection andbreeding which begins with wild plants, butafter some point it can only be carried out withplants under intensive cultivation. Furthermorethe fact that neither these cultivars nor theirputative ancestors are found in the presentnatural vegetation supports the idea that thesevarieties were cultivated by the ancient Maya,but the way in which these plants were cul-tivated by the ancient Maya remains unknown.

hand, Modern Maya homegardens are alsogrounded in some prehispanic practices of treecropping either in cultivation or in the wild.

Comparing the species from the presenthomegardens which are native to theneotropics wi~h the trees which have beenrecorded as economically important for theearly colonial period as we" as for some preclas-sic Maya sites (Marcus, 1982; Miksicek, 1983;Turner and Miksicek, 1984), it can be seen thata significant proportion of the species used inthe present have been economically importantover a long period of time. Of a total of 44native species recorded as growing in modernMaya homegardens, 23 are reported by Marcus(1982) as utilized during the XVI and XVII cen-tury. On the other hand 10 of these species arealso reported by Miksicek (1983) as economical-ly important during the preclassic period atPu"trouser, Belice (Table 3). FurthermoreVhoories (1982) lists 150 plant species whichaccording to that author, could have provideddifferent commodities for export to the Mayahighlands during the Preclassic period as a partof a long distance trade network. Examinationof such a list reveals that 49 of the species werefound either by the present author or by Bar-rera (1980) and Rico-Gray et al. (1991), as grow-ing in modern Maya homegardens.

There is no clear indication of the way inwhich these species were managed in the past.Wild species such as Cedrella odorata. Sabalspp.,Erhetia tinifolia and Manilchara achras couldhave been gathered in the forests or croppedtbrough some system of silviculture as has beensuggested by a number of scholars (Puleston1968 and 1978; Rico-Gray et al., 1985; Gómez-Pompa, 1987; Gómez Pompa et al., 1987; Mc-Ki"op 1988). As indicated by oral traditionrecorded in the field by the present author ,some of these species could have been recentlyintroduced into the homegardens as a way tocope with the progressive scarcity of theseresources resulting from deforestation. On the

o..~

=;~u~

~

.6..6..6.

44

nNOICOLÓGlCA. VOL I, N.. 1, 1992

~

Whether they were cultivated in homegardenssimilar to those of the present Maya, can onlybe learned from intensive archaeological re-search on ancient habitational sites, a field stillunder-studied by Maya Archaeologists.

Floristic Variation and Homegarden Evolution

o..u

:;

~u

...:.,

~'"'

To think of Maya homegardens as uniformagroecosystems is an idea supported by the re-lative cultural and ecological homogeneity ofthe Yucatan Peninsula. However statisticalanalysis of the data on relative abundace of theplant species recorded during the systematicsampling of 60 homegardens reveals the exis-tence of different floristic patterns in variousregions of the Yucatan peninsula (Caballero,1991). It is important to examine these varia-tion patterns because they mirror some evolu-tionary trends of Maya homegardens.

As shown by Caballero (1991) the analysis ofthe overall similarity among homegardens bymeans of ordination techniques gives differentresults when using data on presence and ab-sence of species than when using data on rela-tive abundance of species. Thus a Non MetricalMultidimensional Scaling performed on asimilarity matrix using data on presence andabsence of species shows a close similarityamong most of the homegardens and does notprovide any significant differentiation amongthem (Figure 3).

In contrast, as can be seen from Figure 4, aPrincipal Component Analysis performed on adissimilarity matrix using data on the speciesrelative abundance shows a relatively clear dif-ferentiation ofhomegardens which is a result ofthe dominance of certain plant species andvarieties such as mmón (Brosimum alicastrum ),%ammullo blanco (Annona squamosa), and bonxa'an (Sabal mexicana). These contrastingresults indicate that: a) as suggested by Rico-

Gray et al. (1990), the Maya homegardens aregeneraIly composed by a basic set of species,mainly fruit trees; b) as suggested by the aboveauthors and by Vara (1980), species composi-tion among homegardens varies greatly andthis variation does not have a pattern; c) sig-nificant dissimilarities between homegardensare better due to differences in the relativeabundance of some of the species of the basicset above mentioned. Three main types of Mayahomegardens can therefore be recognized:

1) Generalized homegardens with adominance shared by a series of species, mainlyCit11Lf spp., Byrsonima and other species.

2) Homegardens with a dominance of Sabalmexicana a n d Brosimum alicastrum. Two

45

IAVIER CABALLERO ÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁ

The floristic variation observed in the Mayahomegardens appears to be a result of a histori-cal process of regional economic specialization.For example, the dominance of Sabal in thehomegardens of Ticul and Maxcanu is relatedto the economic importance that palm hand-icraft industry has in these villages. On theother hand, the dominance of Brosimumalicastrum in the homegardens of Pomuch, andTenabo is related to the extensive use that thistree had until recently, for feeding the laboranimals utilized in the "sisal" (Agave spp.) cul-tivation and the cordage industry .

The Future of Maya Homegardens

Figure 4. Projection of 60 homegardens in a two dimensio-nal space of characters (relative abundance of species andvarieties) as obtained from a Principal Component Analysis.Numbers are homegardens: 1-6 Loche; 7-12 Dzonot Ake;13-18 Huayma; 19-24 Chan Kom; 25-30 Xkom Ha; 31-36Ichmul; 3742 Ticul; 43-48; Maxcanu; 49-54 Tenabo; 55-60Pomuch. Source: Caballero (1991). The first two principalcomponents explain 39.6% of the variation. The species-va-rieties with higher loadings in the first principal componentare zaramullo blanco (Annona squamosa) naranja agria (Cilrusauranlium) and naranja dulce (Cilrus sinen.sis). The specieswith higher loadings in the second principal component areSabal mexicana and Brosimum alicaslrum.

The Maya region of Yucatan is undergoing arapid process of transformation as a result ofits incorporation into the cultural and economicmainstream of modern Mexico. In spite of thisprocess of change, the Yucatec Maya are one ofthe Indian groups of Mexico which have main-tained their cultural heritage more than othergroups (Thompson, 1974). The modern Mayahomegardens mirror this double condition ofchange and persistence. Homegardens are sti"an important element in Maya subsistence andalthough the traditional agricultural economy ofthe Maya population has been substituted indifferent regions by market oriented activitiessuch as sisal cultivation, cattle raising and com-mercial fruit tree culture, homegarden cultiva-tion has been kept virtually unmodifiedthroughout the Maya region.

Yet even though they persist as a traditionaleconomic acitvity, Maya homegardens are un-dergoing a process of change. Rico-Gray et al.(1990) have suggested the existence of a trendtowards a change in homegarden structure andfunction in response to the modernization andeconomic transformation in the Yucatan Penin-sula. In fact homegardens have been changing

variants of d1is type of homegarden can be

recognized:a) hornegardens dorninated by Sabal

mexicana.b) hornegardens co-dominated by Sabal

mexicana and Brosimum alicastrum.3) Homegardens with a dominance of An-

nona squamosa and Brosimum alicastrum. Twovariants of this type of homegarden can be

recognized:a) homegardens dominated exclusively by

Annona squamosa.b) hornegardens co-dominated by Annona

squamosa and Brosimum alicastrum.

46

ÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁÁ ETNOECOLÓGlCA, VOL I, N.. 1, 1992

o..u

=;

~u

...:.,

s

~

Maya population; the progressive orientation ofthe local economy to the market; the improve-ment of land transportation; as we" as the in-troduction of tap water which permitshomegarden irrigation, are associated with anincreasing abundance of commercial varietiesmainly of fruit trees in the Maya Homegardens.Even though this trend involves the irreparableloss of the genetic pool of native species, itseems to be one of the consequences of theincorporation of the Maya into the sociocul-tural mainstream of modern Mexico. .

over time in response to regional economictransformations as revealed by the patterns offloristic composition observed in different partsof the Peninsula. Nevertheless at the present,homegarden transformation seems to be ac-celerating throughout the Maya area.

Rico-Gray et al. (1990) have pointed out thatMaya homegardens, mainly those of the vil1agescloser to Merida and other cities, tend to havemore ornamental plants and commercialvarieties of fruit trees at the expense of themore traditional elements of the homegarden.It was not possible to assess this phenomenonfrom the sample of 60 homegardens since thenumber of homegardens sampled in each vil-lage was too smal1. Nevertheless qualitative ob-servations indicate that sociocultural transfor-mations involving different factors such as a thedevelopment of new cultural attitudes of the

Acknowledgments

This research was founded by the ConsejoNacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, México (Grant

.6..6..6.

47

JAVIER CABALLERO AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

PCECBNA-O21704), by the Pacific Ream Projectof the University of California at Riverside andby the Universidad Nacional Autónoma deMéxico. The Centro de Recun'os Bióticos de laPenínsula de Yucatán permitted the use of itsfacilities for this study and provided field assis-tance. I thank the collaboration and advice ofEdilberto Ucan, Salvador Flores and VictoriaSosa from the above institution. I thank CarmenMorales of the Centro Regional de Yucatán of theInstituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia,México for introducing me to the village of Ich-mul. I also thank Linda Newstrom for proofreading the manuscript and Laura Cortes forher assistance in the development of the database for the elaboration of the Appendix I.

References

Alvarez-BuyIla, E. and E. Lazos. 1989. Homegardens of aHumid Tropical Region in Southeast Mexico: An Exam-pIe of an Agroforestry Cropping System in a RecentlyEstablished Community. Agroforestry Systems.

Anderson, E. 1950. An Indian Garden at Santa Luda, Gua-temala. Ceiba 1(2):97-103

Anderson,]. 1979. Traditional Homegardens in Southeast Asia.V International Symposium of Tropical Ecology. Malay-sia.

Anderson, ]. 1986. House garden5-An Appropiate VillageTechnology. In: Korten, D.C. Comunity Management:Asian Experience and Penpectives. Kumarian Press.

Barrera, A. 1980. Sobre la Unidad de Habitación Tradicio-nal Campesina y el Manejo de Recursos Bióticos en elArea Maya Yucatanense. BIOTICA 5(3):11~129.

Basurto, F. 1982. Huertos Familiares en dos ComunidadesNahuas de la Sierra Norte de Puebla: Yancuictlalpan yCuahutapanaloyan. Tesis Profesional. Facultad de Cien-das. UNAM. México.

Brierly, ]. 1976. Kitchen Gardens in the West Indias withContemporary Study from Grenada. journal of TropicalGeograPhy 43:30-40.

Caballero, ]. 1991. Floristic Variation in Modern Maya Ho-megardens: Ethnobiological Implications. In: Gómez-Pompa, A. (ed.) Homegardens of the Maya Area. WestView Press. In Press.

De La Garza, M., A. Izquierdo, M.A. León y T. Figueroa(eds). 1983. Relaciones Histórico-GeográfICas de la Relaci6nde Yucatán. México D.F.: Universidad Nacional AutÓno-ma de México 2 vols.

Dian-a, N. 1975. LeJardinage Urbain et Suburbain au Malile Cas de Bamako. joum. d'Agric Tropic. et BotAppl.18( 12):481-532.

48

~

nNOICOLÓGlCA. VOL I, N.. 1, 1992

Gómez-Pompa. A. 1987. On Maya Silviculture. Mexican Stu-dies 3(1):17

Gómez-Pompa, A, S. F1ores and V. Sosa. 1987. The Pet Kot:A Man-Made Tropical Forest of the Maya. Interciencia

12(1):10-15.Hernández X. E. 1959. La Agricultura. In: Los Recursos

Naturales del Sureste y su Aprovechamiento. Beltrán, E.(ed.), Inst. Mex. Rec. Nat. Renov. 3:3-37.

Kimber, C. 1966. Dooryard Gardens of Martinique. YeaT-book oJ the Association oJ the PacifIC Coast Geographers

28:96-118.Kimber. C. 1978. A F olk Context of Plant Domestication: or

the Dooryard Garden Revisited. American Journal oJ Ca-nada 16(4).

Marcus J. 1982. The Plant World of the Sixteenth-and Se-venteenth Century Lowland Maya. In: F1annery. K. (ed.)Maya Subsistence, New York: Academic Press. pp. 239-273.

McKillop. H. 1989. Ancient Maya AgricultuTe: TTee Croppingat Wild Cay, Belize. Manuscript presented at the 54thAnnual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeo-

logy, At1anta. Georgia.Miksicek, C.H. 1983. Macrofloral Remains of the Pulltrou-

ser Area: Sett1ements and Fields. In: Turner. B.L. andP.D. Harrison (eds). PulltTouser Swamp. Austin: Univer-sity ofTexas Press. pp. 99-104.

Miranda, F. 1958. Estudios acerca de la vegetación. In: Bel-trán. E. ( ed). L()S ReCUf:sOS NatuTales del SUTeste y su Aprove-chamiento. México: Instituto Mexicano de Recursos Natu-rales Renovables. Vol. 2 pp. 215-271.

Puleston. D.E. 1968. Brosimum alicastTUm as Subsistence At-ternative JOT the Classic Maya oJ the CentTal Southern Low-lands. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthro-pology, University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia.

Puleston. D.E. 1978 Terracing Fields, and Tree Cropping in

ey

~~u...:,.9&

the Maya Lowlands: A New Perspective of the Geo-graphy of Power. In: Harrison, P.D. and B.L Tumer II(eds). Prehispanic Maya Agriculture. Albuquerque: Univer-sity ofNew Mexico Press. pp. 201-225.

Rico-Gray, V., A. Gómez-Pompa and C. Chan. 1985. LasSelvas Manejadas por los Mayas de Yohaltún, Campe-che, México. BIOTICA 10(4): 321-327.

Rico-Gray, V.,J.G. García-Franco, A. Puch y P. Sima. 1988.Composition and Structure of a Tropical Dry Forest inYucatan,Mexico. Internationaljournal ofEcology and Envi-ronmental Sciences 14:21-29.

Rico-Gray, V.,J.G. García-Franco, A. Chemas,J.G. Puch y P.Sima. 1990. Species Composition, Similarity, andStructure of Mayan Homegardens in Tixpehual and Tix-cacaltuyub, Yucatan, Mexico. Economic Botany 44(4): 470-487

Rico-Gray, V., A. Chemas y S. Mandujano. 1991. Uses ofTropical Deciduous Forest Species by the Yucatecan Ma-ya. Agroforestry System.s ( 13) In Press.

Sanabria, O.L. 1986. El Uso del Recurso Forestal en unaComunidad Maya. Etnoflora Yucatanense. Vol 2. Mérida,México: Instituto Nacional de Recursos Bióticos.

Sánchez, M.C. 1991. Uso y Manejo de lo Leña en X-uilub,Yucatán. Master Dissertation. Departamento de Biología,Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónomade México, México.

Smith, E. and Cameron, M. 1977. Ethnobotany of the Puuc,Yucatan. Economic Botany 81:93-110.

Soemarwoto, O and I. Soemarwoto. 1982. Homegarden: itsNature, Origin and Future Development. In: EcologicalBasis for Rational Resource Utilization in the Humid Tropú;¡of South East Asia. pp. 130-139.

Sosa, V.,J.S. Flores, V. Rico-Gray, R. Lira y JJ. Ortiz. 1985.Lista Florística y Sinonimia Maya. Etnoflora YucatanenseFasc. 1. Xalapa, México.

Thompson, R. 1974. The Winds of Tomorrow: Social Changein a Maya Town. Chicago and London: The University ofChicago Press.

Turner, B. L. and Miksicek. 1984. Economic Plant SpeciesAssociated with Prehistoric Agriculture in the MayaLowlands. Economic Botany 38(2): 179-193.

Tozzer, A. (ed). 1941 Landa's Relación de las Cosas deYucatán: A Translation. Papers of the Peabody Museum ofAmerican Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University,Vol XVIII. Cambridge.

Vara, A. 1980. La Dinámica de la Milpa en Yucatán: elSolar. In: Hemández, X. E. (ed). Seminario sobre Pro-ducción Agricolo en Yucatán. Secretaría de Programa-ciÓn y Presupuesto. Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán.Mérida.

Vargas, C.A. 1983. El Ka 'anche': Una Práctica Horticola Ma-ya. BIOTICA 8(2):151-173.

Voorhies, B. 1982. An Ecological Model of the Early Mayaof the Central Lowlands. In: Flannery, K. (ed.) MayaSubsistence, New York: Academic Press. pp. 65-95.

.6.""""

49

Q)

Eccc::flt;'-'+

=Q)

~ciííi"-C

X)

~o-

"'-c-.2

.Q

)-a..

~-c

Q)

~

cu

~~

C/)

>-

..Q

) 3:

..c O

--o]"' ..

c Q

)Q

) E

"E

cc

c

g>~

E

co~

..cc Q

)

>--:E

c-~

o

o~-oQ.

-co '-~

..9! o

Q...C

E

tc

o"'

~

c~c .

cC

>.~

c c

.-c~

Q.

,-C/)

c>c

"' .-

c..~-c

Q)

Q)

c-c

o'-O

-Cu

cQ

) o

'- v

"' Q

)Q

) "'

.o Q

)Q

)..CQ

.-C

/)-c.c

-c.~

c

1fQ.c

Q..-

4: .!!!

zo-t~w

WC

D:::I~O

:)uzw(/):)

>-

u

~:f;

w::>

u<J

~w

w~

n ..

w~z-1~o~V)

wownoU'I

"'I"...M~c:'G

>:J0-0>c:

1~xo-~O)

.~t:O)

noow

I:

<..2

wO

u .~

<

"'

~

~

~~ !e

-i-i

cU

,loQl

<

u ...

w

.-:)

U~

~-i-i-i-i-i-i-i-i-i-i

c: -

==

= .-:)

o o

o o

c o

o o

o o

oe

Q.. Q

I QI Q

I ~

QI Q

I QI Q

I G>

G>

~

., <

~

.2

:) :)

:) :>

:)

:) :)

:>

:) :)

U

.-"'C)

e- e-

e- e-

e- e-

e- e-

e- e-

O¡c:

:) :)

:) :>

:)

:) :)

:) :)

:)Z

§oQ.Q

.Q.Q

.Q.Q

.Q.Q

.Q.Q

...c<

,J;v;v;v;¡,)v)v;v;v)v)v;

N

.-"'

"'.."'

Oln

--"'M

"'O

InIr')'0.."'Ino-.-

ON

'O~

1r')1n"'..

'O1n"'~

'01n

-g- """'0~

0~

°o-O.."'O

"'In'O

'O1l1

~0.-M

'ON

MM

In ..'0~

lnM'O

o-=

o-=

o-=

.-=

.-=

.-=

o-=

o-=

o-=

o"t: o-=

o-=

~~

~~

~~

~~

~~

~~

.1::..1::..1::..1::.~~

~~

~~

~~

'...(0)'...(0)000 0(0)

,... ..o.

.,....-00.-50.00.000~

r-..L(\~

L(\~L(\.-

ocQ.c u ~

-

6) o

o -

o. .o

-.o Q

&~

]]~]~

§]]~-

c-coo

o-*~oC

c.8o

o .-

o .o

.-c o

.2..0 c

¡:=

,.2 o

o

Ea-f;~

EO

oo~)(

~~

'-o """

"' ~

~

,

~

~

~

~

ÁÁ

Á50

""'N

V)

'()o.. N

~~

"0

."t=

."t=

"t=;)~

=>

;)'-'-'-'-

~-~

~

M""-

O"

"M

"C

X>

-o .111

"ot""ot"g)-o

00§ §

00~

~~

Q

)U

) "'"'

U)

Q) Q

)V

) V

) .

.-"

-J~~

oO

u

u "'

w

o O

O

°E

~

.~

~

~

o

~

SE2

~

5-z

U)

0:1:1

Oc:e-e-g

ZO

:l:lOZ

c:Q.Q

.c:<

~~

~~

.~1 or...M"";-'o"'~o~0-"'

<

o

0"0-0=

...

9 ...O

c: 0

E0

E

O

.000 O

"0

D

c: V

0

c:O0

c: ...

oCc:

Q

Q~

go ~

E

O)

0 .-

.-Q.

.-~

. .-O

>

- ~

>

- "58

Q.o~

E:)

Eo~

~

E

~c:ooeC

eo°..r:

o C

-~lJ

~o.cE

'oc-g

~

~

"'O....,

~:Ic~'O

"'tc:~

I").-~

"":--o>

-

~4)~

V

)"t:

...~..2

.--o

E~..cv(/)~~.e:..

o.c:

w..Jo

<

o .>

w

'- ::.

U.Q

'-::.

Q)

'- Q

.

z o

o>

- U

~j

o E

.

B.::...c

o<S

::a::,,",

-0~\t')

.80-

E~

:J -

C:N

0-

g~

~E

.~

8~

...

~A1~v.,

.",~

Q

I

.2"G1.t:

~

"

(O),...

~,.,;

ta3:~~

eo

QI

~coC

.-

0'"6.!:!

0)(

41O

) ...

~

E

~w

.0

.CU

-~

e~

<0-

U

V

8w

e

v~

vO

<oc(u

0: o

('4-M

'00 ~

MM

M

VOL I, N.. 1, 1992

¿¿¿¿Á

53

VOL I, N.. 1, 1992

"""

""""'54

~