J Continuous Doppler echocardiography and coarctation of ...aortaatthelevel ofdiaphragmobtained from...

Transcript of J Continuous Doppler echocardiography and coarctation of ...aortaatthelevel ofdiaphragmobtained from...

Br Heart J 1990;64:133-7

Continuous wave Doppler echocardiography andcoarctation of the aorta: gradients and flowpatterns in the assessment of severity

Julene S Carvalho, Andrew N Redington, Elliot A Shinebourne, Michael L Rigby,Derek Gibson

AbstractIndices of the severity of coarctationderived from non-invasive Dopplerechocardiography were compared withmeasurements derived from cardiaccatheterisation and angiography. In 24Doppler studies from 17 children instan-taneous peak systolic and diastolicgradients and time to half peak systolicand diastolic velocities were comparedwith the ratio of the coarctation dia-meter to the diameter of descendingaorta at the level of diaphragm obtainedfrom angiographic systolic frames ofthe aorta. A high peak systolic gradient(>40 mm Hg) or long time to half peakdiastolic velocity (> 100 ms) (that is,maintenance of flow in diastole) wereboth highly specific (100%) in detectingcoarctation of the aorta where theangiographic ratio was <0'5. Diastolicmeasurements, however, were more sen-sitive (79% both for peak diastolicgradient and for time to half peak dias-tolic velocity) than systolic (57% for peaksystolic gradient and 64% for time tohalf peak systolic velocity). Even highersensitivity (93%) was obtained when thepeak systolic gradient was > 40 mm Hgor the time to half peak diastolic velocitywas > 100 ms.Examination by continuous wave

Doppler echocardiography is an effec-tive non-invasive method of assessingthe severity of coarctation of the aorta,particularly when systolic and diastolicevents are considered together. Thisapproach overcomes the relatively lowsensitivity of peak systolic gradientalone.

Department ofPaediatric Cardiology,Brompton Hospital,LondonJ S CarvalhoAN RedingtonE A ShinebourneML RigbyDepartment ofCardiology, BromptonHbspital, LondonD GibsonCorrespondence toDr Julene S Carvalho,Department of PaediatricCardiology, BromptonHospital, National Heart andLung Institute, FulhamRoad, London SW3 6HP.Accepted for publication30 January 1990

Clinical presentation of coarctation of theaorta varies with the age of the patient and theseverity of coarctation. In the neonatal period,heart failure may be precipitated by closure ofthe ductus arteriosus, blood flow to the lowerbody having been dependent on ductalpatency. Older children are usually symptomfree. Non-palpable or weak femoral pulseswith normal or increased pulses in the arm are

the most specific findings that lead to thediagnosis, but these useful clinical findingsmay be absent. In the neonatal period theremay be a large ductus and in older children an

extensive collateral circulation may result innormal femoral pulses. Blood pressure

measurements in the arms and legs andgradients measured across the coarctation areaby Doppler echocardiography can give someindication of severity. Differences in pres-sures, however, depend not only on theseverity of the coarctation but also on flowfrom collaterals and on cardiac output.

Instantaneous peak systolic gradientsmeasured by Doppler techniques correlatedwell with the severity of coarctation.' 3 Insome patients after coarctation repair, how-ever, we found increased velocities in thedescending aorta not associated with clinicallysignificant coarctation. These high velocitiesmay be related to turbulence around theoperation site. The flow velocity pattern inthe descending aorta in coarctation can beabnormal in diastole as well as in systole.45Studies of the duration of flow in the descend-ing aorta with measurements of accelerationtime and anterograde flow time improved thecorrelation between catheterisation pressuregradients and Doppler derived gradients.6However, measurements related to flow dura-tion were not studied in detail. We thereforefurther investigated ways in which gradientsand flow patterns in the descending aorta canbe used to predict the angiographic severity ofcoarctation.

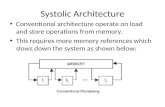

Patients and methodsBetween January 1987 and June 1989 westudied 17 children with coarctation of theaorta who had cardiac catheterisation and con-tinuous wave Doppler studies performedwithin 48 hours of each other. Doppler studieswere performed with either a Doptek Spectra-scan or a Hewlett Packard (Model 77020AC)2-5 MHz probe. An electrocardiogram wasrecorded simultaneously on paper at 100 mm/sspeed. Seven patients underwent angioplasticballoon dilatation and measurements weretaken before and after the procedure. Thus 24pairs of measurements were available foranalysis. We used continuous wave Dopplerechocardiography from a standard suprasternalposition to measure maximum velocity in thedescending aorta. We measured the followingvariables (fig 1) and calculated gradients usingthe modified Bernoulli equation (gradient =4V2 )7: (a) instantaneous peak systolic gradient(mm Hg) corresponding to the maximalmeasured velocity; (b) early (peak) diastolicgradient (mm Hg) arbitrarily measured at theend ofthe T wave on the electrocardiogram; (c)systolic velocity halftime (ms)-that is, time tohalf peak systolic velocity from the onset of

133 on A

ugust 22, 2020 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.64.2.133 on 1 A

ugust 1990. Dow

nloaded from

Carvalho, Redington, Shinebourne, Rigby, Gibson

1llllllllllllAXlllllt!l!lllllllllll!lllIllild!llIllllIllll I l' 10

jl._________

.

I

Yi..~~~~~~~~~1 I-iPF.,&I ,X .1 s it4

, aob...*I.'

I IlOoms

Figure I Continuous wave Doppler echocardiogram recordedfrom a suprasternalposition in a patient with severe coarctation, showing systolic (A) and diastolic (B)measurements. PSG or PDG, peak systolic or diastolic gradient; T PSV or T PDV,time to halfpeak systolic or diastolic velocity.

ejection; and (d) diastolic velocity half time(ms)-that is, time taken for the diastolicvelocity to fall to half its (peak) early value (atthe end of the T wave).We studied systolic frames that showed the

maximal diameter on the aortogram or leftventriculogram and which showed the coarcta-tion site and descending aorta at the level ofthediaphragm. A diagram was copied from theprojected aortogram in straight lateral or leftanterior oblique view in all but two patients,when an anteroposterior projection was used.To control for age, weight, and x ray magnifica-tion, we measured the minimal diameter of thecoarctation and expressed it as a ratio of thedescending aorta at the level of the diaphragm(fig 2). Two independent observers analysed22 of the 24 angiograms without previousknowledge of the measurements and subjec-tively graded the coarctation as severe,moderate, mild, or non-existent.

ANALYSIS OF DATAThe observer's subjective (but blind) angio-graphic assessment of severity was comparedwith the angiographic ratio. The data wereevaluated for interobserver variablity, for therelation of subjective category to angiographicratio, and for whether Doppler measurementsand angiographic ratio correlate with decisionto intervene. The angiographic ratio was usedas the reference standard for the non-invasive

measurements obtained with continuous waveDoppler.Each of the Doppler measurements and the

angiographically determined ratios were placedin rank order. Matrices of Spearman rankcorrelation coefficients for the basic data werethen calculated to identify which Dopplermeasurements, when analysed as independentmeasurements, correlated with the angio-graphic index of severity.

ResultsTable 1 shows the results of all measurements.

ANGIOGRAPHIC ASSESSMENT (TABLE 2)All patients with an angiographic ratio < 05were considered to have severe or moderatelysevere coarctation by both observers and torequire relief of the coarctation (surgery orballoon dilatation). All angiograms with ratios> 065 were graded as mild or trivial coarcta-tion by both observers and were not regarded asrequiring intervention. In five patients theratios were between 05 and 0-65, and two(ratios 0-58 and 0-63) of these patients wereconsidered to have none/mild coarctation byboth observers. In the remaining three patients(ratios 0-57, 0-6, and 0-63) the coarctation wasregarded as mild by one and moderate by theother observer. None of these three cases wasregarded by the observers as requiring (nor didthey undergo) intervention.

Figure 2 Systolicframe in lateral projection of anangiogram of the ascending aorta. The measurements ofcoarctation diameter and diameter of descending aorta atthe level of diaphragm that were used to calculate theangiographic ratio are shown.

w.,*-0--WV--NNW ". * ."e ... . & :..-

134

id LV eL-. -f 1, I

f."-M I., I

on August 22, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://heart.bm

j.com/

Br H

eart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.64.2.133 on 1 August 1990. D

ownloaded from

Continuous wave Doppler echocardiography and coarctation of the aorta: gradients andflow patterns in the assessment of severity

Table I Measurements by Doppler echocardiography and angiography

PSG PDG TjPSV TIPDVPatient Ratio (mm Hg) (mm Hg) (ms) (ms)

1 Before 0 33 49 32 210 1351 After 0-72 29 9 120 302 0-68 28 6 90 453 Before 0 50 50 35 105 553 After 0-63 17 1 60 504 Before 0-63 33 28 120 805 Before 0 57 18 5 100 206 0 49 21 16 160 1357 0 45 52 44 260 2158 0-13 63 50 325 3359 0-29 25 23 150 12510 0-22 45 32 370 40011 Before 0 43 39 2 110 1012 Before 0 30 43 27 85 3512 After 1-00 17 0 7 110 013 Before 0-41 60 48 135 12513 After 0-82 14 4 110 2514 0-27 12 5 175 24015 Before 0-25 37 20 200 12015 After 0-60 33 6 120 2016 Before 0-20 55 30 245 17016 After 0-57 32 11 155 8017 Before 0-27 31 12 120 13017 After 0-80 12 0 85 0

Before and After refer to balloon dilatation.PSGorPDG, peak systolic or diastolic gradients; Ti, time to halfpeak systolic or diastolic velocity.

Table 2 Angiographic assessment of severity ofcoarctation

Patient Ratio Observer I Observer 2

1 Before 0 33 Severe Severe1 After 0-72 Mild Mild2 0-68 Mild Mild3 Before 0 50 Severe Severe3 After 0-63 Moderate Mild4 Before 0-63 Mild Mild5 After 0 57 Moderate Mild6 049 Severe Severe7 045 Moderate Moderate8 0-13 Severe Severe9 0-29 Severe Severe10 0-22 Severe Severe11 Before 0-43 Severe Mod severe12 Before 0 30 NA NA12 After 1-00 NA NA13 Before 0-41 Severe Severe13 After 0-82 None None14 0-27 Severe Mod severe15 Before 0-25 Severe Mod severe15 After 0-60 Moderate Trivial16 Before 0-20 Severe Severe16 After 0-58 None Trivial/none17 Before 0-27 Severe Severe18 After 0-80 None None

NA, not available; Mod severe, moderately severe. Before andAfter refer to balloon dilatation.

DOPPLER ASSESSMENTBecause none of the patients with an angio-graphic ratio > 05 was thought by eitherobserver to require surgery or balloon dilata-tion, we elected to make this value a clinicallyimportant discriminant. We therefore exam-ined the sensitivity and specificity of Dopplermeasurements for detecting patients withratios above and below this value.High systolic gradients or long decay times

were specific for significant coarctation. In thisseries we obtained 100% specificity and 100%predictive value for detecting coarctation withan angiographic ratio < 0 5 if the peak systolicgradient was > 40 mm Hg and/or time to halfpeak diastolic velocity was > 100 ms. Conver-sely, lower sensitivities were seen for each ofthe individual measurements, although dias-tolic variables were more sensitive and hadbetter predictive values for a negative test thansystolic measurements. This relatively low sen-

sitivity of the Doppler technique was greatlyimproved when we considered the peak systolicgradient and peak diastolic velocity half timetogether-that is, whether there was either apeak systolic gradient > 40 mm Hg or a longtime to half peak diastolic velocity (> 100 ms)(table 3). A plot of the angiographic ratios andtime to half peak diastolic velocity shows thevalidity of this particular measurement (fig 5).

Matrices of the Spearman correlation co-efficient showed that each of the individualDoppler measurements correlated with theangiographic ratio. Table 3 gives details ofeachcorrelation coefficient and significance level.All values were significant (p < 0-003), but thenegative correlations between times to halfpeak systolic and to half peak diastolicvelocities and the angiographic ratios werestronger than the correlation between peaksystolic and diastolic gradients and the angio-graphic ratios. So it is likely that the longer thetime to half maximal velocities (persistence offlow in diastole) the smaller the ratios (the moresevere the coarctation).

DiscussionIn the presence of coarctation of the aortavarious factors can influence the flow pattern inthe descending aorta.8 The cross sectional areaand length of the narrowed segment and thepresence of a collateral circulation or a largeductus arteriosus are contributing factors, as isthe cardiac output. The resultant pattern offlow to the descending aorta is, therefore,related to a complex interaction of all thesefactors. The limitations of using the Dopplertechnique to diagnose coarctation of the aortain neonates have been recently emphasised.9The pattern of flow velocity in the descend-

ing aorta in the presence of coarctation isqualitatively characteristic. High systolicvelocities reflect the presence of a pressuredrop between the proximal and distal aortaduring ejection. High velocities also persistduring diastole. In mild cases these have re-turned to baseline by mid diastole; but whencoarctation is more severe, high velocities con-tinue throughout diastole. It thus seems to usthat not only might the patterns of diastolicflow provide a means of measuring the severityof coarctation but also that such patterns mayreflect an aspect of the disturbance to normalphysiology quite distinct from a simple reduc-tion in peak perfusion pressure. This diastolicpressure drop can be considered as equivalentto a potential generated by a capacitance decay-ing across a resistance; so it can be modelled asan exponential. We therefore chose to measureits severity as a simple velocity half time.Obviously, conditions are more complex thanthis, particularly where there is a large col-lateral flow which could cause pressure toequilibrate rapidly regardless of the severity ofthe coarctation itself. Even so, we believed thatmeasuring the decay time would give informa-tion related to the severity of obstruction in thepresence of collaterals, and that the clinicalvalue of such measurement might usefully beexplored.

135 on A

ugust 22, 2020 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.64.2.133 on 1 A

ugust 1990. Dow

nloaded from

Carvalho, Redington, Shinebourne, Rigby, Gibson

a a a a Iaa.a *a a .a a I ma a a I a a s.1 a a

I IlOOms

so _

Figure 3 Continuous wave Doppler echocardiogram recorded in a patient with secoarctation of the aorta (ratio = 0 27). Note slight increase in maximal systolicvelocity (gradient = 12 mm Hg) but long diastolic velocity half time (240 ms).

* m Our results showed that the specificity ofDoppler measurements in identifying severecoarctation of the aorta is high if there is animportant gradient or flow that is maintained indiastole. In six patients severe coarctationwould have been missed if only high peaksystolic gradients had been considered. This

- low sensitivity could be greatly improved byanalysing the peak diastolic velocity half time.

AL This approach makes it possible to identifythose patients with severe coarctation in whomlower velocities (and consequently lowergradients) are present. In this series only onepatient (case 1 1) with a severe lesion would nothave been definitely identified by the combina-tion of the two measurements. However, evenin this case the peak systolic gradient was nearly40 mm Hg.This analysis shows that the validity of the

Doppler technique for assessment ofseverity ofcoarctation of the aorta can be significantlyimproved by the additional assessment of flowpatterns. The factors that influence the pres-ence of high velocity across the narrowedsegment or persistence offlow in diastole in thedescending aorta are certainly complex, but thepresence of only one of these measurementsseems to be enough to confirm that the coarcta-tion is appreciable and warrants intervention.A very small number of patients, however,

evere may still require cardiac catheterisation ifmeasurements are borderline and there is un-certainty about the severity of coarctation onclinical grounds.

Table 3 Performance of Doppler echocardiographic measurements in detecting coarctation when the angiographicratio was < 0 5... . .. _...I ..._^.. . I . . ._I

...

. -0

_D m

Sensitivity Predictive value Predictive value Spearman rank(%) Specificity ofpositive test of negative test correlation (p)

(%) (%) (%)

PSG > 40 mm Hg 57 100 100 63 -0 57(0 003)

Ti PSV > 140ms 64 90 90 64 -0-67(< 0001)

PDG > 15mmHg 79 90 92 75 -0-61(0-001)

TiPDV > 100ms 79 100 100 77 - 0-76(< 0001)

PSG > 40mm Hg orTiPDV > 100ms 93 100 100 91

PSG or PDG, peak systolic or diastolic gradients. Ti PSV or Ti PDV, time to half peak systolic or diastolic velocity.

1.1-

0 0.9-t-

. 0.7-0.cLa

0.5._0c.4 0.3

0.1Figure 4 Continuouswave Dopplerechocardiogram recordedin a patient with severecoarctation (ratio =0 30), high peak systolicgradient (43 mm Hg), andshort decay time (35 ms).

0@0

* 08 *

0

0 50

0

S

200 250T 1/2 PDV (ms)

0

300 350 400100 150

Figure 5 Angiographic ratio plotted against time to halfpeak diastolic velocity to showthe validity of this measurement. There were nofalse positive (right upper corner) andthree false negative results (left lower corner). True positive measurements are shown inthe right lower corner and true negative on the left upper corner.

,,M l, .."

-r .:-."' !"'IT i. la o% ;. 7,

136 on A

ugust 22, 2020 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.64.2.133 on 1 A

ugust 1990. Dow

nloaded from

Continuous wave Doppler echocardiography and coarctation of the aorta: gradients andflow patterns in the assessment of severity

1 Wyse RKH, Robinson PJ, Deanfield JE, Tunstall PedoeDS, Macartney FJ. Use of continuous wave Dopplerultrasound velocimetry to assess the severity ofcoarctationof the aorta by measurement of aortic flow velocities. BrHeart J 1984;52:278-83.

2 Robinson PJ, Wyse RKH, Deanfield JE, Franklin R,Macartney FJ. Continuous wave Doppler velocimetry asan adjunct to cross sectional echocardiography in thediagnosis of critical left heart obstruction in neonates.Br Heart J 1984;52:552-6.

3 Marx GR, Allen HD. Accuracy and pitfalls of Dopplerevaluation of the pressure gradient in aortic coarctation.JAm Coll Cardiol 1986;7:1379-85.

4 Hatle L, Angelsen B. Doppler ultrasound in cardiology:physical principles and clinical applications. Philadelphia:Lea and Febiger, 1985:217-21.

5 Houston AB, Simpson IA, Pollock JCS, Jamieson MPG,

Doig WB, Coleman EN. Doppler ultrasound in theassessment of severity of coarctation of the aorta andinterruption ofthe aortic arch. Br Heart J 1987;57:38-43.

6 Syamasundar Rao P, Carey P. Doppler ultrasound in theprediction of pressure gradients across aortic coarctation.Am Heart J 1989;118:299-307.

7 Hatle L, Angelsen B. Doppler ultrasound in cardiology:physical principles and clinical applications. Philadelphia:Lea and Febiger, 1985:24.

8 Teirstein PS, Yock PG, Popp RL. The accuracy ofDopplerultrasound measurement of pressure gradient acrossirregular, dual and tunnellike obstructions to blood flow.Circulation 1985;72:577-84.

9 Wilson N, Sutherland GR, Gibbs JL, Dickinson DF,Keeton BR. Limitations of Doppler ultrasound in thediagnosis of neonatal coarctation of the aorta. Int JCardiol 1989;23:87-9.

137 on A

ugust 22, 2020 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://heart.bmj.com

/B

r Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.64.2.133 on 1 A

ugust 1990. Dow

nloaded from