Indian Painting The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16.

-

Upload

herbert-summers -

Category

Documents

-

view

226 -

download

0

Transcript of Indian Painting The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16.

Indian Painting

The Dying princess

Ajanta, cave no-16

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

Introduction: The Ajanta caves are situated in

the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra.

A total of about 30 caves are situated at Ajanta. Paintings and sculptures were made in these caves by the Buddhists from 2nd century B.C. to 7th century A.D.

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

The monastery, one of the oldest in the world, first reveals the Hinayana period (200 B.C. to 200 A.D), where Buddha is represented only by symbols, or in his supposed previous existence as related in the Jataka stories. We see this chiefly in the Chaitya (place of worship) of cave no.10 (2nd century B.C) and cave no.9 (1st century B.C).

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

Near the end of the 5th C. A.D. (450-650 A.D.) the Mahayana influence took over, as seen in caves no. 16,17,2, and 1. This brought with it the portrayal of the Buddha in human form.

In order to proclaim the message of the Buddha, the monks employed artists who turned the stone wall into picture blook of his life and teaching

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

Representations from the Jataka tales illustrate his intelligence, noble character, selfless service and compassion by means of legends from his previous births.

Though the pictures depict stories related to the Buddha, the artists portrayed at the same time the costumes and customs of their own epoch, especially the extravagance of the court life.

Nor did they overlook life’s comedy and tragedy, its pathos and humour.

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

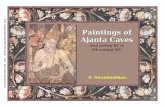

The Dying Princess The Dying Princess is considered to be

one of the important paintings produced in cave no. 16 at Ajanta.

The scene sows the critical stage of Nanda’s wife.

Nanda is a cousin brother of Buddha. She fell ill after hearing the decision of

her husband that to renounce the crown and to become a monk.

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

It is a depiction of poetic tragedy. For pathos, sentiments, and the unmistakable way of telling its story this picture cannot be surpassed in the history of art.

The artists of Florentine could have put better drawing, and the Venetian better color, but neither could have thrown greater expression into it.

The dying woman with drooping head, half-closed eyes, and languid limbs, reclines on a bed, the like of which may be found in any native house of the present day.

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

She is tenderly supported by a female attendant, while another with eager gaze is looking into her face, and holding the sick woman’s arm as if in the act of feeling her pulse.

The expression of her face is one of deep anxiety, as she seems to realize how soon life will be vanished in the one she loves.

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

Another female behind attends with a Pankha while two men on the left are looking on with the expression of profound grief depicted in their faces.

Below are seated on the floor other relations, who appear to have given up all hope and to have begun their days of mourning, for one woman has buried her face in her hand and apparently is weeping bitterly.

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

This painting can be included in the category of ‘classical’ in a qualitative sense.

The movement of line is sure and inevitable, without trick or cliché.

The illusion of warm, rounded flesh is conveyed by unobtrusive modeling and shading. The color remains fresh even now.

The color remains cool and fresh even now, so that the paintings present themselves to the eye in the different light.

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

Stylistic features: A higher degree of craftsmanship,

incorporating all the rules lay down by ancient Indian treatises on painting and aesthetics, marks the execution of these religious themes.

One finds here, for instance, the six limbs of painting as enumerated in Vishnudharmothara (a text on aesthetics).

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

Male and female figures confirm to the traditional standards of beauty, with her arched eyebrows, long almond-shaped eyes, straight noses, full lips and slightly pointed chins.

Minute changes in the poses, gestures and direction of the faces create variety, so that, surprisingly, there is neither obviousness nor repetitiveness.

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

The artists of Ajanta used perspective in a different way. A kind of multiple perspectives has been introduced where different objects are perceived as if they were seen from within the panel.

With only six pigments in his hand, the Ajanta artist created the vocabulary of the entire color-range, each speaking its own language and giving meanings to others. Far from dramatizing by climaxing color-contrasts, he took choice to the more refined expression of tonalities.

The Dying princess Ajanta, cave no-16

Here the relationship of proportion is relative, not based on empiric knowledge but depend on emotional importance, spiritual reality-each different situation demanding a new evaluation.