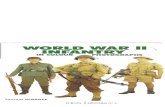

In Living Colour -...

Transcript of In Living Colour -...

1

Nomusa Makhubu In Living Colour Three woven photographs 63 x 92 cm 2015 Critical Text

In Living Colour is a series of three woven photographs. Each image is made through weaving two photographs together. These

photographs interrogate two different African cities through a focus on the visual images of urban life. The first is Lagos. Often referred to

as a 'mega-city', Lagos is a fast-changing city that has richness of life. The second city is Cape Town. While it is defined as a 'World City' and

named the 'World Design Capital 2014', Cape Town is arguably the most brutally inequitable city in Africa. The two cities are the first in a

broader study of African cities which interrogates spatio-temporal social situations through a documentation and ‘merging’ of specific

annual events and ‘everyday’ scenes. This on-going project focusses of African cities and the conceptualisation of space and time as a social

construct.

The title of the project, In Living Colour, is drawn from the American television series which had a predominantly black cast and used ghetto

African-American humour. This title has some resonance with an event that I had been documenting that takes place in Cape Town

annually: The Cape Coons Carnival or Kaapse Klopse or Cape Town Minstrels. This event has origins in American minstrelsy where whites

ridiculed blacks through blackface performances and the construction of caricatures such as Mammy, the Jezebel, the slave and the mulatto.

The Cape Town minstrels, however, began in the 1800s when slaves were given a day off on the 2nd of January since the Dutch (who settled

and governed the Cape in the 1600s) celebrated New Year’s day on the 1st of January. The carnival is also known as Die Tweede Nuwejaar

which means ‘The Second New Year’. To this day, Cape Minstrelsy practiced by the Cape Coloured community has a significant cultural

presence. The word ‘Coloured’ is a racial category that the Apartheid government used to classify people of mixed race who are

descendants of the pastoralist Khoe, San and Xhosa; the English and Dutch settlers, French Huguenots; and slaves who were imported from

Madagascar, West and East Africa, India and Indonesia. The offspring of Europeans and slaves, ‘Cape coloureds’ and ‘Cape Malays’, were

highly sought after as slaves (Giliomee and Mbenga 2007). The Coon Carnival is the reclamation of space through cyclical time (historical

time repeats each year).

2

Two photographs, woven together

3

4

The second set of images (above) was taken in Nigeria at a time when I was travelling by bus from Lagos to Abuja. These were not of a

particular event but were a process of capturing views of the street at each intersection at various intervals from the window of the bus. I

had been in Lagos to write about Nollywood. Since In Living Colour is a title of a television series that was unlike mainstream series, I

thought about it in relation to Nollywood serial films and their deliberate choice of local and not mainstream humour or other local issues.

Time in Nollywood is an interesting element. The use of the serial format and repetition as technological manipulation as well as aesthetic

strategy in Nollywood films draws our attention to the way in which time is configured in Nollywood; not only in its representation of the

past and the present but also in the way that it alludes to the organisation of time within social spaces (hair salons and video parlours).

There is an ambiguous sense of ‘free’ time but one in which people do not necessarily have the means to use their time. The word ‘free’ in

this case may not be entirely appropriate but it can be used it to demonstrate the intricacies of lived time in Lagos as it is represented in

Nollywood video-film. There is also an uneasy problematic contrast of images in media of time spent in a ‘developed’ country, where people

are rushing to work and spending time ‘constructively’, with images of people in a ‘developing’ country who seem idle and engaged in

endless waiting. The same contrast exists for urban and rural dispositions. This contrast makes it seem as though time spent in industry is

time better spent than in peasantry and vagrancy, and, therefore, produces a different meaning for ‘free’ time. It is as if there is a hypothesis

that ‘free’ time in a ‘developed’ country is regarded as deserved leisure time, whereas in a ‘developing’ country it illustrates laziness.

In film generally, the time and space of reality is physically contracted but expanded in our minds. This is the magic of film: it gives the

illusion of time (brings the past into the present and provides a visualisation of the future) while it alludes to time as a construct. For

instance, the viewer can imagine “long, long ago” without needing the chronological details that lead us to present events. The viewer can

imagine that a character has driven for hours or days without having to watch hours of the process of travelling. Generally film

differentiates the space and time of the film from that of our own. Dudley Andrew (1976: 18) argues that “at its primary level, the mind

animates the sensory world with motion”. The emphasis is on the mind as a “raw material” that produces motion pictures, organises the

world and, through images, “creates a meaningful reality” (Andrew 1976: 18). The viewer fills in by imagination the ‘unnecessary’ omitted

parts of a narrative. Lengthy uneventful or uninformative human practices are thus avoided in the narration unless if they form part of the

core meaning of the film. By contrast, Nollywood video-films include lengthy uneventful wide-shot activities. The viewer may watch a

character walk a distance for over ten minutes even though this activity may not be linked to the core meaning of the film, such that the

walking appears banal and meaningless. It is expanded everyday practice. The sense of boundlessness that is characterised by the long

scenes is not uncommon in African film. Teshome Gabriel (1995: 83) argues that “Western films manipulate ‘time’ more than ‘space’”

whereas “Third World films seem to emphasise ‘space’ over ‘time’. Communication in folk tradition and African cinema, Gabriel (1995: 83)

observes, is a “slow-paced phenomenon” that may include ‘non-dramatic’ elements that may be regarded as boring “cinematic excess” in

5

Western cinematic experience but are significant in African cinematic experience. The repetition of images and scenes as well as the long

takes functions as the re-evaluation of events that have already taken place in the film and to situate the viewer within the cultural relations

of the community in which the narrative is based. Moreover, the logistics that are involved in moving between areas in the city of Lagos are

vastly time-consuming. Time, comes across as protracted and not always constructively spent.

The third set of images in the In Living Colour triptych (see images below) is a combination of and image from Lagos and another from Cape

Town. One focusses on class and the other focusses on race. They are both a contrast between labour time and leisure time/ industrial time

and family time: the two female workers/ cleaners as opposed to the beach scene. The combination of the two cities uses David Harvey’s

(201) notion of space-time compression through which he highlights a crisis in our experience of time and space, “a crisis in which spatial

categories come to dominate those of time, while themselves going through such a mutation that we cannot keep pace”. This set of

photographs highlights the contradictions of the concept of progress through which economic relations with the West and neoliberal

reforms have created, in African urban spaces, the different experiences of time and space where the idea of progress seems to constantly

signify its opposite.

Furthermore, this series brings two geographical locations in one pictorial space to question the assumed universality and objectivity of

time and place. Through the representation of the two different cities as well as the documentation of events and ‘the everyday or quotidian

practices’, I regard time and space as relational. The project is on-going and seeks to interrogate different spatio-temporal social situations

in various cities in the continent.

6