imaging of the stomach in children: beyond pyloric stenosis

Transcript of imaging of the stomach in children: beyond pyloric stenosis

INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS cont.

EOSINOPHILIC GASTROENTERITIS

Eosinophilic gastritis is an uncommon condition and rarely seen in infancy. It may occur alone or, more commonly, as part of a more diffuse gastroenteritis involving the small intestine in particular. This heterogeneous group of eosinophilic gastroenteropathies includes eosinophilic esophagitis, gastroenterocolitis, and gastritis. They have in common a similar pathologic process - eosinophilic inflammation

of the gut. Diagnosis is made by pathological demonstration of eosinophilic infiltration, which may be patchy and involve different layers of the bowel wall, and by the exclusion of other causes of eosinophilia, such as parasites, infla- mmatory bowel disease, and vasculitis. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present in up to 50% of patients. The exact pathophysiologic cause is unknown and the role of allergens is debated.

On barium studies, eosinophilic gastritis may demonstrate a lacy mucosal pattern affecting the gastric antrum or, more commonly, a marked nodular appearance in the gastric antrum with relative sparing of the body and fundus. Eosinophilic gastritis may mimic idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis demonstrating the typical sonographic findings of thickened muscular layer and elongated pyloric channel. Hummer-Ehret et. al. have suggested that demonstration of abnormal thickening of the mucosa and submucosal layers on ultrasound in the setting of a thickened muscular layer may be indicative of eosinophilic infiltration. A reported association of IHPS and eosinophilic gastroenteritis raises interesting questions about the possible etiologic relationship between the two entities.

Figure 5

17 year old male presents with vomiting and weight loss.

Images from an air contrast UGI show marked narrowing and irregularity of the pylorus & duodenal cap (arrows). Biposy at UGI endoscopy confirmed Crohn’s disease.

Figure 6

8 year old male presents with bright red blood per rectum and abdominal pain (a) and endoscopy photo (b).

UGI (a) shows nodular fold thickening in the gastric antrum (arrows). UGI endoscopy photograph shows thickened antral fold (arrow) and biopsy confirmed Crohn’s disease. Terminal ileitis was also present.

CROHN’S DISEASE

The frequency of pediatric Crohn’s disease involvement of the upper GI tract is often underestimated. Gastric lesions detected at endoscopy are often not reported on UGI examinations. Endoscopic and histological involvement has been reported with rates varying between 30% and 80%. Upper GI tract Crohn’s disease is most common in the stomach (67%) and said to occur in the gastric antrum with greater frequency then the body of stomach. The duodenum is reported to be involved in 12-22% of patients. Findings on UGI series may help to localize disease prior to upper endoscopy. In many cases, granulomas are only found on upper endoscopy and histologic findings are equivocal in the colon.

Figure 7

A 1 year old male presented with a prolonged history of vomiting and failure to thrive. There was a background of recurrent superficial skin and respiratory tract infections.

Upper GI barium study demonstrates concentric narrowing of the gastric antrum (arrow). Subsequent investigations confirmed chronic granulomatous disease.

CHRONIC GRANULOMATOUS DISEASE

Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood is an inherited disorder of neutrophil phagocytosis characterized by recurrent infections with catalase-positive organisms. The disorder is much more common in males than females (>80:20) and most patients present within the first 2 years of age. CGD can involve the gastrointestinal tract from the esophagus to the rectum but the most common gastrointestinal manifestation is chronic antral gastritis leading to progressive narrowing and gastric outlet obstruction. Upper GI series reveals narrowing of the antropyloric lumen secondary to chronic inflammation and fibrosis. Sonographic evaluation demonstrates circumferential wall thickening at the antrum. Histologically, there is inflammation with granuloma formation and infiltration of lipid-laden histiocytes involving the lamina propria, submucosa, smooth muscle, and serosa. No organisms are usually isolated from these lesions.

IMAGING OF THE STOMACH IN CHILDREN: Beyond Pyloric StenoSiSMichael Moore MB BCh, Ruth Lim MD, Sjirk J Westra MD and Katherine Nimkin MDPediatric Radiology , Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA • Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

REFERENCES

INTRODUCTION

Gastric abnormalities in children are relatively uncommon. Imaging of the stomach in children is frequently performed on the vomiting infant; hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is a relatively common entity seen in this setting. We present imaging studies of the stomach in a variety of less common pathologic conditions.

CONCLUSION

Multimodality imaging, including upper GI series, CT, US, MRI and PET are useful tools when evaluating less common abnormalities of the stomach in children.

CONGENITAL/DEVELOPMENTAL CONDITIONS

Figure 8

A 13 year old female with a known diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis presented for routine screening abdominal MR to follow known renal angiomyolipomas.

A heterogeneous, T2 bright (a) rounded mass (arrow) is seen in the left supra-renal area, demonstrating marginal enhancement on T1 fat-saturated image (b). An ultrasound (c) demonstrates an echogenic mass in the same area (arrows). These findings were concerning for an adrenal angiomyolipoma. However, abdominal CT with oral contrast (d), performed previously at another institution, demonstrates this mass to be a gastric diverticulum (arrow), a finding confirmed at a later MR, when air was seen within the “mass”.

GASTRIC DIVERTICULAGastric diverticula (GD) are the least common of all gastrointestinal diverticula. The majority (75%) are located within a few centimeters of the gastroesophageal junction, usually on the lesser curvature or posterior aspect. Although there is a wide variety in shape and size, typical diverticula are 1–6cm in diameter. These juxtacardiac diverticula are congenital in origin and covered by all layers of the normal gastric wall. The remaining (25%) gastric diverticula are smaller in size and located in the pylorus or gastric antrum. GD may be seen at cross-sectional imaging including ultrasound, CT and MR and may be mistaken for more sinister supra-renal pathology.

Figure 9

A neonate presented with intolerance of feeds and recurrent non-bilious vomiting.

A plain abdominal radiograph demonstrates marked distension of the stomach with an absence of distal bowel gas. Diagnosis: Pyloric Atresia

PYLORIC ATRESIACongenital pyloric atresia (CPA) accounts for less than 1% of intestinal atresias. The gastric outlet obstruction may be secondary to a true atresia or caused by a membrane at the pylorus or gastric antrum. The atresia may be an isolated abnormality or may be associated with epidermolysis bullosa/aplasia cutis congenita and other gastrointestinal atresias. The presence of associated anomalies is a contributing factor for the reported high mortality.

A high index of suspicion is necessary to avoid confusion of CPA with duodenal atresia, particularly on X-rays. The plain abdominal X-ray shows a solitary bubble due to a gastric entrapment of air. A long stretched-out peak at the pylorus is regarded as a pathognomonic sign of complete pyloric closure. A double bubble may, however, be seen in cases with prolapse of a pyloric membrane into the duodenum, thus imitating duodenal atresia. The possibility of associated intestinal atresias must always be kept in mind and to exclude or locate associated colonic atresia, a preoperative barium enema is advocated. The presence of calcification on plain abdominal X-ray should raise the possibility of associated heredity multiple intestinal atresia (HMIA).

Figure 10

2 year old with vomiting.

Image from an UGI series shows mass effect on the greater curvature of the gastric antrum. Diagnosis: Gastric Duplication Cyst

GASTRIC DUPLICATION CYSTS

Gastric duplications are rare, comprising only 4-9% of intestinal duplications, are more common in girls and occur along the greater curvature in most instances. Most gastric duplications are attached to the wall of the stomach and have been classified as tubular or cystic, the latter usually not communicating with the stomach. Distal antral or pyloric cysts can present with gastric outlet obstruction, mimicking hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Ectopic pancreatic tissue is present in 37% of gastric duplications.

Gastric duplications typically present with partial obstruction before 12 months of age and an upper abdominal mass is often palpable on examination. Ultrasound displays the cystic nature, anatomic location and characteristic inner echogenic mucosal and outer hypoechoic muscle layers of gastrointestinal duplication cysts. Computerized tomography (CT) is useful in defining the nature of the cyst and its relationship to other structures. The cyst usually has an attenuation similar to that of water, and a rim of calcification may be visible, even in children.

Figure 114 year old with acute onset of vomiting.

Chest radiograph (a) shows large left effusion, left basilar lung opacity, and elevated left hemi-diaphragm. Image from UGI series (b) shows pylorus (arrow) to the left of the GE junction with close approximation of the pylorus and GE junction. Mesenteroaxial volvulus was found at surgery.

2 year old with cerebral palsy and chronic abdominal pain.

Two images from UGI series show the greater curvature of the stomach lying superior to the lesser curvature. Organoaxial volvulus was found at surgery.

GASTRIC VOLVULUS

Gastric volvulus is an abnormal rotation of the stomach leading to partial or total obstruction. Depending on the axis of rotation, it may be classified into organoaxial, mesenteroaxial and mixed. In mesenteroaxial (MA) volvulus, the stomach rotates around an imaginary (short) axis passing through the greater and lesser curvatures such that the greater and lesser curvatures are in their usual positions relative to each other but there is reversal of the relationship of the gastroesophageal junction and pylorus. This creates a narrow pedicle about which the stomach can twist, leading to gastric obstruction and ischemia and presents as an acute emergency. In organoaxial (OA) volvulus, the stomach rotates around an imaginary (long) axis passing between the esophago-gastric junction and the pylorus, such that the greater curvature is positioned superior to and to the right of the lesser curvature. The stomach might flip upward along its long axis, but because it does not twist on itself there is no risk of ischemia. Obstruction, however, can occur. Organoaxial volvulus is the most common whilst the mixed variety is extremely rare and difficult to differentiate both radiologically and intraoperatively.

On barium studies, organoaxial (OA) volvulus is diagnosed when the greater curvature of the stomach lies superior to the lesser curvature and the pylorus points inferiorly. Mesenteroaxial (MA) volvulus is diagnosed when the pylorus is displaced superiorly and toward the left (shortening the distance between the pylorus and gastroesophageal junction), and the pylorus overlaps the gastroesophageal junction or gastric fundus.

Figure 12

A 12 month old male infant presented with vomiting and a palpable mass in the mid-abdomen.

An enhanced CT of the abdomen demonstrates an ectopically placed spleen in the midline as well as an obstructed stomach with evidence of pneumatosis (arrow).

WANDERING SPLEEN with GASTRIC VOLVULUS

Wandering spleen is a rare condition characterized by the absence or underdevelopment of one or all of the ligaments that hold the spleen in its normal position in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. Most cases in children present when the child is younger than 1 year and there is a male predominance. Splenic torsion, complicating 64% of pediatric cases of wandering spleen, is usually clockwise and can cause vascular congestion, infarction, and even gangrene of the spleen. Wandering spleen and gastric volvulus share a common cause, the absence or laxity of intraperitoneal visceral ligaments.

Figure 13

12 year old girl with acute abdominal pain and vomiting.

CT of the abdomen (a) reveals pneumoperitoneum (arrows) and a heterogeneous mass filling the stomach (b, arrows). Trichobezoar with gastric perforation was found at surgery.

9 year old girl presents with a small bowel obstruction 3 days after surgical removal of gastric bezoar.

CT of the abdomen shows small bowel obstruction (c) secondary to retained trichobezoar in the jejunum (d, arrow).

TRICHOBEZOAR

Trichobezoars are most commonly found in young females, typically in the setting of an underlying psychiatric disorder. Trichobezoar formation occurs when ingested hair strands are retained in the folds of the gastric mucosa because their slippery surface prevents propulsion by peristalsis. This large quantity of hair becomes matted together and assumes the shape of the stomach, usually as a single mass.

Rapunzel syndrome is a rare form of trichobezoar. It is named after a charming tale written in 1812 by the Brothers Grimm about a young maiden, Rapunzel, with long tresses who lowered her hair to the ground from high in her prison tower to permit her young prince to climb up to her window and rescue her. Originally described in 1968, more than 25 cases have since been reported in the literature, with variable clinical features and varied diagnostic criteria. The typical diagnostic features include a trichobezoar with a tail, extension of the tail at least to the jejunum, and symptoms suggestive of obstruction. All the cases reported in the literature are females with the exception of one male patient who ate his sisters’ hair.

Figure 14

Newborn presents with bilious vomiting.

Scout film (a) and UGI (b) reveals complete duodenal obstruction (arrow). Malrotation with volvulus was found at surgery. 2 weeks following surgery the neonate remained intolerant of feeds as a result of a secondary duodenal stenosis. An attempt was made at passing a naso-jejunal feeding tube under fluoroscopic guidance (c). Inadvertant gastric perforation occurred (d).

GASTRIC PERFORATION

Neonatal gastric perforation is a rare condition, associated with high mortality and morbidity and an acute surgical emergency that must be promptly recognized and treated. Such patients usually present with acute onset of rapidly progressive abdominal distension and massive pneumoperitoneum. The majority of cases present within the first 7-10 days of life. Although gastric distension, instrumentation, and necrotizing enterocolitis have been cited as predisposing factors to neonatal gastric perforation, most perforations appear to be truly spontaneous.

ACQUIRED CONDITIONS

Figure 15

An 18 year old male with a family history of polyposis syndrome.

A double contrast upper GI barium study demonstrates multiple polyps throughout the gastric fundus and body (arrows). No small bowel polyps were seen. Biopsy at endoscopy revealed fundic gland polyps and hamartomatous-type polyps with focal low grade dysplasia. Colonoscopy confirmed multiple adenomatous polyps and the patient underwent a total colectomy.

GARDNER SYNDROME

Gardner syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the triad of colonic polyposis, multiple osteomas and mesenchymal tumors of the skin and soft tissues. Symptoms are usually evident by the 20th year of age, but they may present anytime between 2 months and 70 years. In general the cutaneous and bone abnormalities develop approximately 10 years prior to polyposis. The gastrointestinal manifestations of Gardner syndrome include colonic adenomatous polyps, gastric and small intestinal adenomatous polyps and peri-ampullary carcinomas. Gastric fundic gland polyps occur in approximately 90% of affected individuals. Most of these lesions are hyperplastic and carry no malignant potential. However, adenomatous polyps and their progression to gastric cancer have rarely been described.

Figure 16A 14 year old female presented with abdominal pain and vomiting.

Coronal HASTE (a) and axial T2 (b) MR images of the abdomen show a mass arising from the lesser curvature of the stomach (arrows). T1 enhanced axial image shows enhancing liver lesions (c, arrows). PET image (d) reveals increased uptake in the gastric and liver lesions (arrows).Pathology: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the stomach with liver metastases.

GIST

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are uncommon mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Pediatric GIST cases are rare and have been reported to represent only 1.4% of all GIST cases. Cases of pediatric GIST can be sporadic, familial, or found in association with Carney’s triad (GIST, pulmonary chondroma, and paraganglioma) or neurofibromatosis type 1. Pediatric GIST is a unique subtype with a tendency to present with gastric multinodular or multifocal disease. Gastric GISTs in children have mainly epithelioid morphology, often occur in the antrum, and have a somewhat unpredictable but slow course of disease. They have malignant potential, but their behavior is often difficult to predict. In children, two peaks of incidence have been demonstrated - <1-year-old and between 10 and 15 years old. Pediatric GIST affects females more commonly than males, as opposed to adult GIST where males are more commonly affected.

On MR imaging, gastric GIST often present as a large exophytic mass with variable T1 and T2 signal corresponding to areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. Careful evaluation for abnormal increased T2 signal may help in identifying multifocal disease within the gastric wall.

Figure 17

10 year old girl with abdominal pain and weight loss.

CT image with oral contrast shows marked thickening of the gastric wall with luminal narrowing. Diagnosis: Burkitt Lymphoma

BURKITT LYMPHOMA

Primary malignant tumors of the stomach are uncommon in children and mainly consist of lymphoma and sarcoma. The majority of primary gastric lymphomas are high-grade large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL). Among Caucasian children under the age of 15 years, lymphomas account for nearly 10% of all the malignant disease, of which 40% are histologically NHL. In the pediatric population 30-50% of all NHL will be of Burkitt type. Burkitt Lymphoma (BL) is a highly aggressive neoplasm of mature B cells, is one of the fastest growing tumors with a potential tumor-cell doubling time of < 24 hours and 90% of these will typically present with an abdominal tumor. In childhood, primary of the stomach is extremely rare, accounting for < 2% of pediatric lymphoma cases. The few reported cases of gastric BL suggest that these tumors present as large masses with extensive local infiltration, but without a predilection for significant nodal or distant disease.

NEOPLASTIC CONDITIONS

Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis

1.Teele RL, Katz AJ, Goldman Teele RLH, Kettell RM. Radiographic features of eosinophilic gastroenteritis (allergic gastroenteropathy) of childhood. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979 Apr;132(4):575-80.

2.Aquino A, Dòmini M, Rossi C, D’Incecco C, Fakhro A, Lelli Chiesa P. Pyloric stenosis due to eosinophilic gastroenteritis: presentation of two cases in mono-ovular twins. Eur J Pediatr. 1999 Feb; 158(2):172-3.

3.Hümmer-Ehret BH, Rohrschneider WK, Oleszczuk-Raschke K, Darge K, Nützenadel W, Tröger J. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis mimicking idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Radiol. 1998 Sep; 28(9):711-3.

4.Snyder JD, Rosenblum N, Wershil B, Goldman H, Winter HS. Pyloric stenosis and eosinophilic gastroenteritis in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987 Jul-Aug;6(4):543-7.

5.Blankenberg FG, Parker BR, Sibley E, Kerner JA. Evolving asymmetric hypertrophic pyloric stenosis associated with histologic evidence of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Pediatr Radiol 1995;25(4):310-1.

Pediatric Crohn’s

1.Lenaerts C, Roy CC, Vaillancourt M, Weber AM, Morin CL, Seidman E. High incidence of upper gastrointestinal tract involvement in children with Crohn disease. Pediatrics. 1989 May;83(5):777-81.

2.Ruuska T, Vaajalahti P, Arajärvi P, Mäki M. Prospective evaluation of upper gastrointestinal mucosal lesions in children with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994 Aug;19(2):181-6.

3.Castellaneta SP, Afzal NA, Greenberg M, Deere H, Davies S, Murch SH, Walker-Smith JA, Thomson M, Srivistrava A. Diagnostic role of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004 Sep; 39(3):257-61. Erratum in: J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005 Feb; 40(2):244.

4.Oberhuber G, Hirsch M, Stolte M. High incidence of upper gastrointestinal tract involvement in Crohn’s disease. Virchows Arch. 1998 Jan; 432(1):49-52.

Chronic Granulomatous Disease

1.Khanna G, Kao SC, Kirby P, Sato Y. Imaging of chronic granulomatous disease in children. Radiographics. 2005 Sep-Oct;25(5):1183-95.

2.Iannicelli E, Matrunola M, Almberger M, Salvini V, Roggini M. Chronic granulomatous disease with gastric antral narrowing: a study and follow-up by MRI. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(7):1259-62.

3.Smith FJ, Taves DH. Gastroduodenal involvement in chronic granulomatous disease of childhood. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1992 Jun;43(3):215-7.

4.Kopen PA, McAlister WH. Upper gastrointestinal and ultrasound examinations of gastric antral involvement in chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Radiol. 1984;14(2):91-3.

Gastric Diverticula

1.Lopez ME, Whyte C, Kleinhaus S, Rivas Y, Harris BH. Laparoscopic excision of a gastric diverticulum in a child. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007 Apr;17(2):246-8.

2.Ciftci AO, Tanyel FC, Hiçsönmez A. Gastric diverticulum: an uncommon cause of abdominal pain in a 12 year old. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Mar;33(3):529-31.

3.Elliott S, Sandler AD, Meehan JJ, Lawrence JP. Surgical treatment of a gastric diverticulum in an adolescent. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Aug;41(8):1467-9.

4.Schwartz AN, Goiney RC, Graney DO. Gastric diverticulum simulating an adrenal mass: CT appearance and embryogenesis. AJR, 1986 Mar; 146, (3) 553-4.

Pyloric atresia

1.Parshotam G, Ahmed S, Gollow I. Single or double bubble: sign of trouble! Congenital pyloric atresia: report of two cases and review of literature. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007 Jun;43(6):502-3.

2.Al-Salem AH. Congenital pyloric atresia and associated anomalies. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007 Jun;23(6):559-63. Epub 2007 Mar 28.

Gastric Duplication Cysts

1.Master V, Woods RH, Morris LL, Freeman J. Gastric duplication cyst causing gastric outlet obstruction. Pediatr Radiol. 2004 Jul;34(7):574-6.

2.Stringer MD, Spitz L, Abel R, Kiely E, Drake DP, Agarwal M, et al . Management of alimentary tract duplication in children. Br J Surg 1995;82:74-8.

3.Singh S, Gupta R, Mandal AK. Complete gastric duplication cyst. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005 Jul-Aug;24(4):170-1.

4.Carachi R, Azmy A. Foregut duplications. Pediatr Surg 2002;18:371-4.

Gastric Volvulus

1.Oh SK, Han BK, Levin TL, Murphy R, Blitman NM, Ramos C. Gastric volvulus in children: the twists and turns of an unusual entity. Pediatr Radiol. 2008 Mar;38(3):297-304.

2.Liu HT, Lau KK. Wandering spleen: an unusual association with gastric volvulus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007 Apr;188(4):W328-30.

3.Spector JM, Chappell J. Gastric volvulus associated with wandering spleen in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 2000 Apr;35(4):641-2.

4.Garcia JA, Garcia-Fernandez M, Romance A, Sanchez JC. Wandering spleen and gastric volvulus. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24(7):535-6.

Trichobezoars

1.Newman B, Girdany BR. Gastric trichobezoars--sonographic and computed tomographic appearance. Pediatr Radiol. 1990;20(7):526-7.

2.Naik S, Gupta V, Naik S, Rangole A, Chaudhary AK, Jain P, Sharma AK. Rapunzel syndrome reviewed and redefined. Dig Surg. 2007;24(3):157-61. Epub 2007 Apr 27.

Neonatal Gastric Perforation

1.Abadir J, Emil S, Nguyen N. Abdominal foregut perforations in children: a 10-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2005 Dec;40(12):1903-7.

2.Im SA, Lim GY, Hahn ST. Spontaneous gastric perforation in a neonate presenting with massive hydroperitoneum. Pediatr Radiol. 2005 Dec;35(12):1212-4. Epub 2005 Aug 12.

3.Duran R, Inan M, Vatansever U, Aladağ N, Acunaş B. Etiology of neonatal gastric perforations: review of 10 years’ experience. Pediatr Int. 2007 Oct;49(5):626-30.

Gardner Syndrome

1.Fotiadis C, Tsekouras DK, Antonakis P, Sfiniadakis J, Genetzakis M, Zografos GC. Gardner’s syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 Sep 14;11(34):5408-11.

2.Sarre RG, Frost AG, Jagelman DG, Petras RE, Sivak MV, McGannon E. Gastric and duodenal polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis: a prospective study of the nature and prevalence of upper gastrointestinal polyps. Gut. 1987 Mar;28(3):306-14.

3.Ushio K, Sasagawa M, Doi H, Yamada T, Ichikawa H, Hojo K, Koyama Y, Sano R. Lesions associated with familial polyposis coli: studies of lesions of lesions of the stomach, duodenum, bones, and teeth. Gastrointest Radiol. 1976;1(1):67-

GIST

1.Hayashi Y, Okazaki T, Yamataka A, Yanai T, Yamashiro Y, Tsurumaru M, Kajiyama Y, Miyano T. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor in a child and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005 Nov;21(11):914-7.

2.Egloff A, Lee EY, Dillon JE. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of stomach in a pediatric patient. Pediatr Radiol. 2005 Jul;35(7):728-9. Epub 2005 Mar 31.

3.Miettinen M, Lasota J, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach in children and young adults: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 44 cases with long-term follow-up and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005 Oct;29(10):1373-81.

4.Park J, Rubinas TC, Fordham LA, Phillips JD. Multifocal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the stomach in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Radiol. 2006 Nov;36(11):1212-4. Epub 2006 Sep 13.

Burkitt Lymphoma

1.Grewal SS, Hunt JP, O’Connor SC, Gianturco LE, Richardson MW, Lehmann LE. Helicobacter pylori associated gastric Burkitt lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008 Apr;50(4):888-90.

2.Moschovi M, Menegas D, Stefanaki K, Constantinidou CV, Tzortzatou-Stathopoulou F. Primary gastric Burkitt lymphoma in childhood: associated with Helicobacter pylori? Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003 Nov;41(5):444-7.

3.Kurugoglu S, Mihmanli I, Celkan T, Aki H, Aksoy H, Korman U. Radiological features in paediatric primary gastric MALT lymphoma and association with Helicobacter pylori. Pediatr Radiol. 2002 Feb;32(2):82-7. Epub 2001 Nov 24.

Figure 4

17 year old female with recurrent vomiting and peripheral eosinophilia.

Ultrasound (a) reveals antral wall thickening (arrow). Contrast enhanced CT abdomen (b, c) shows antral wall thickening (arrows) and massive ascites. Upper endoscopy confirmed eosinophilic gastritis. Ascitic fluid contained 95% eosinophils. Patient responded well to steroids and dietary restriction.

a b c

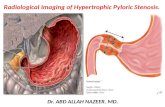

Figure 3

6 week old male with pyloric stenosis, for comparison.

More typical uniform muscular hypertrophy in a classic case of HPS.a

Figure 2

8 week old male infant with vomiting and failure to thrive.

Pyloric muscle thickening is present measuring 4-5mm with change in thickness during the exam, atypical for pyloric stenosis. There are prominent mucosal and submucosal layers (arrows). Upper GI endoscopy showed hemorrhagic and ulcerated mucosa in the gastric antrum and colonoscopy revealed evidence of allergic colitis. Pyloromyotomy was not performed and patient improved with dietary modification.

a b

Figure 1

17 week old female, s/p pyloromyotomy at age 11 weeks for pyloric stenosis, who presents with persistent vomiting.

There is elongation and narrowing of the pyloric channel which appears asymmetric and changeable during the examination. Pyloric muscle thickening is present (arrows), ranging from 3.5-5mm. Endoscopy confirmed eosinophilic allergic gastritis. Patient improved with dietary modification.

a b

INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

a b c

a b

a

a b c d

a

a

a b

c d

a b c

a b

c d

a

b c d

a b c

a b c d

a