High Return, Low Risk (1)

-

Upload

carlos-casanello-pfeiffer -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of High Return, Low Risk (1)

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 1/13

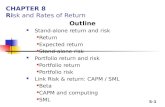

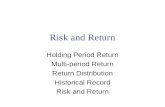

3 Journal of Marketing

Vol. 70 (January 2006), 3–14

© 2006, American Marketing Association

ISSN: 0022-2429 (print), 1547-7185 (electronic)

Claes Fornell, Sunil Mithas, Forrest V. Morgeson III, & M.S. Krishnan

Customer Satisfaction and Stock Prices: High Returns, Low Risk

Do investments in customer satisfaction lead to excess returns? If so, are these returns associated with higher

stock market risk? The empirical evidence presented in this article suggests that the answer to the first question isyes, but equally remarkable, the answer to the second question is no, suggesting that satisfied customers are eco-nomic assets with high returns/low risk. Although these results demonstrate stock market imperfections withrespect to the time it takes for share prices to adjust, they are consistent with previous studies in marketing in thata firm’s satisfied customers are likely to improve both the level and the stability of net cash flows. The implication,implausible as it may seem in other contexts, is high return/low risk. Specifically, the authors find that customer sat-isfaction, as measured by the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI), is significantly related to market valueof equity. Yet news about ACSI results does not move share prices. This apparent inconsistency is the catalyst forexamining whether excess stock returns might be generated as a result. The authors present two stock portfolios:The first is a paper portfolio that is back tested, and the second is an actual case. At low systematic risk, both out-perform the market by considerable margins. In other words, it is possible to beat the market consistently by invest-ing in firms that do well on the ACSI.

Claes Fornell is Donald C. Cook Professor of Business Administration and Director of the National Quality Research Center (e-mail: [email protected]), Forrest V. Morgeson III is a research scientist, National Quality Research Center (e-mail: [email protected]), and M.S. Krishnan is Professor of Business Information Technology, Area Chair, and Mary and Mike Hallman Fellow (e-mail: [email protected]), Stephen M. Ross School of Business, University of Michigan. Sunil Mithas is an assistant

professor, R.H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland (e-mail:[email protected]). The authors thank John Cattier, Stefan Dragolov,Janice Kwan, Eli Dragolov, and Steven Erisch for providing research assistance in collecting necessary data for this study.They also acknowl- edge useful comments and help from David VanAmburg and Jaesung Cha of National Quality Research Center at University of Michigan during the progress of the study. The authors are grateful to Ramanath Subra- manyam for his help and comments during early stages of this research.Financial support for this study was provided in part by the Michael R. and Mary Kay Hallman Fellowship at the Stephen M. Ross School of Busi- ness, University of Michigan.

Does the satisfaction of a company’s customers haveanything to do with the company’s stock price? In away, it must. Otherwise, it would be necessary to go

back to the drawing board of how capitalistic market theoryis supposed to work. The empirical literature on the natureof the relationship is growing, but it is still in its infancy inmany respects. Empirical results (Anderson 1996; Ander-son, Fornell, and Lehmann 1994; Anderson, Fornell, andMazvancheryl 2004; Bolton 1998; Fornell 2001; Ittner andLarcker 1996, 1998; Rust, Moorman, and Dickson 2002)point toward a significant relationship between customersatisfaction and economic performance in general, but less

is known about how the satisfaction of companies’ cus-tomers translates into securities pricing and investmentreturns, and virtually nothing is known about the associatedrisks. The tacit link between buyer utility and the allocationof investment capital is a fundamental principle on whichthe economic system of free market capitalism rests. The

degree to which capital flows from investors actually movein tandem with consumer utility is a matter of significantimportance because it is an indication of how well (orpoorly) markets truly work. A parallel, but narrower, issueis the extent to which equity markets themselves are effi-cient. The assertion in efficient markets theory is that finan-cial prices accurately reflect all public information at alltimes, but financial assets can be correctly priced in equitymarkets even if consumer sovereignty is restricted in prod-uct markets. In a monopoly, for example, dissatisfied buyerscannot punish the seller by taking their business elsewhere,and capital flows are not likely to correspond with con-

sumer utility, but that does not in itself imply that capitalmarkets are inefficient. However, efficient allocation of resources in the overall economy and consumer sovereigntydepend on the joint ability of product and capital markets toreward and punish companies such that firms that fail to sat-isfy customers are doubly punished by both customerdefection and capital withdrawal. Similarly, firms that dowell by their customers would be doubly rewarded by morebusiness from customers and more capital from investors.

We begin by estimating the relationship between cus-tomer satisfaction and market value of equity. As expected,we find a strong relationship. This prompts the question,How do investors react to news about changes in customer

satisfaction? Despite the significant relationship betweencustomer satisfaction and market value, we find no evidencethat they react in a timely manner. Is this because the newsis somehow factored into share prices already, or is it due tomarket imperfections? The evidence suggests the latter.Two stock portfolios, one paper strategy that is back testedand another describing an actual case, lead to similar con-clusions: It is possible to beat the market consistently withinvestment decisions based on customer satisfaction. Per-haps even more remarkable is that these results are notassociated with a risk premium. Indeed, the opposite is true;

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 2/13

4 / Journal of Marketing, January 2006

the systematic risk is low relative to the market. Althoughthese results may appear too good to be true and puzzlingfrom a conventional financial perspective, we present argu-ments suggesting that they are in line with empirical find-ings both in marketing and in the literature on customersatisfaction.

Customer Satisfaction: EconomicEffects

We now turn to the fundamentals behind the relationshipbetween customer satisfaction and stock prices. Both basicneoclassical economics and marketing theory provide ageneral case for a positive association. Conversely, severalmarket factors may contribute to a negative relationship. Inaddition to market factors, there are other circumstances inwhich the association could actually be negative. We dis-cuss both categories and empirically analyze stock marketreaction to quarterly news releases from the American Cus-tomer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) (Fornell et al. 1996). Bycontrolling for other firm-specific news, we test the effectof news announcements about customer satisfaction onstock prices.

Real economic growth depends on the productivity of economic resources and the quality of the output (as experi-enced by the user) that those resources generate. In the finalanalysis, expanding economic activity per se is not what isessential. Both marketing and neoclassical economics viewconsumer utility, or satisfaction, as the real standard foreconomic growth. The extent to which buyers financiallyreward sellers that satisfy them and punish those that do notand the degree to which investment capital reinforces thepower of the consumer are fundamental to how marketsfunction. A well-functioning market allocates resources,including capital, to create the greatest possible consumersatisfaction as efficiently as possible. A dissatisfied buyer

will not remain a customer unless there is nowhere else togo or it is too expensive to get there.Restrictions on consumer choice may be good for the

monopolist but, in general, are considered harmful to theeconomy. In a competitive marketplace that offers meaning-ful consumer choice alternatives, firms that do well by theircustomers are rewarded by repeat business, lower priceelasticity, higher reservation prices, more cross-sellingopportunities, greater marketing efficiency, and a host of other things that usually lead to earnings growth (Fornell etal. 1996).

To what degree do markets actually reflect the norma-tive tenets of market theory? Under what circumstanceswould news about increasing customer satisfaction con-tribute to higher stock prices? Under what circumstanceswould it have the opposite effect? From a cursory glance atthe literature, it is tempting to assume that news about risingcustomer satisfaction would have an immediate and positiveeffect on stock prices. Beginning with the early contribu-tions of Bursk (1966) and Jackson (1985), there is substan-tial conceptual logic and empirical evidence to suggest thatthe health of a firm’s customer relationships is a relevantindicator of firm performance (Ambler et al. 2002; Bell etal. 2002; Berger et al. 2002; Blattberg and Deighton 1996;

1For example, in a study of a catalog retailer, Reinartz andKumar (2000, 2002) find a weaker-than-expected (but significant)relationship between customer retention and profitability. Thestrength of any customer retention–profitability relationshipdepends on the cost of creating and maintaining repeat customers.If repeat business is created through price discounts or othermeans that do not cause an upward shift in the firm’s demandcurve, the relationship will be weaker. Thus, repeat business pro-duced by higher customer satisfaction will be more profitable ingeneral than repeat business generated by price discounts.

Bolton, Lemon, and Verhoef 2004; Fornell 1995, 2001; For-nell et al. 1996; Hogan, Lemon, and Rust 2002; Rust et al.2004). For example, it has been found that customer satis-faction has a negative impact on customer complaints and apositive impact on customer loyalty and usage behavior(Bolton 1998; Fornell 1992). Increased customer loyaltymay increase usage levels (Bolton, Kannan, and Bramlett2000), secure future revenues (Rust and Keiningham 1994;Rust, Moorman, and Dickson 2002), reduce the cost of future transactions (Reichheld and Sasser 1990), lower

price elasticity (Anderson 1996), and minimize the likeli-hood of customer defection (Anderson and Sullivan 1993;Mithas, Jones, and Mitchell 2004). Customer satisfactionmay also reduce costs related to warranties, complaints,defective goods, and field service costs (Anderson, Fornell,and Lehmann 1994; Fornell 1992; Garvin 1988). Empiricalevidence also suggests that customer perceptions of supe-rior quality are associated with higher economic returns(Aaker and Jacobson 1994; Capon, Farley, and Hoenig1990; Fornell 2001). Naumann and Hoisington (2001)report positive associations among employee satisfaction,customer satisfaction, market share, and productivity mea-sures at IBM Rochester. Several case-based research studies

also find that customer satisfaction is positively associatedwith employee loyalty, cost competitiveness, profitable per-formance, and long-term growth (Heskett, Sasser, andSchlesinger 1997; Reichheld and Teal 1996). Finally, in arecent study of the relationship between customer satisfac-tion and shareholder return, Anderson, Fornell, and Maz-vancheryl (2004) find a strong relationship between cus-tomer satisfaction and Tobin’s q (as a measure of shareholder value) after controlling for fixed, random, andunobservable factors.

If, as the empirical evidence suggests, customer satis-faction tends to improve repeat business, usage levels,future revenues, positive word of mouth, reservation prices,

market share, productivity, cross-buying, cost competitive-ness, and long-term growth and if it tends to reduce cus-tomer complaints, transaction costs, price elasticity, war-ranty costs, field service costs, defective goods, customerdefection, and employee turnover, it seems logical to expectthat these effects will eventually affect stock prices andcompany valuations. Even if a substantial portion of theempirical findings were dismissed,1 it would be difficult notto take seriously the notion of customer satisfaction as areal, albeit intangible, economic asset. Putting the argumentin the context of economic assets allows for a logical link toconventional capital asset pricing (see Fornell and Werner-felt’s [1987, 1988] economic analysis of the value of keep-ing customers and the more recent work by Wayland and

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 3/13

Customer Satisfaction and Stock Prices / 5

Cole [1997], Srivastava, Shervani, and Fahey [1998], Grucaand Rego [2005], Gupta, Lehmann, and Stuart [2004],Anderson, Fornell, and Mazvancheryl [2004], Hogan,Lemon, and Rust [2002], Venkatesan and Kumar [2004],and Rust, Lemon, and Narayandas [2005]). Srivastava,Shervani, and Fahey (1998) provide the conceptual logic formore categorically drawing the link from the empiricalfindings on customer satisfaction to stock returns and share-holder value. They identify four major determinants of acompany’s market value: (1) acceleration of cash flows, (2)

increase in cash flows, (3) reduction of risk associated withcash flows, and (4) increase in the residual value of thebusiness. Not only does the customer asset, as defined bythe expected future discounted net cash flow from currentand future customers, influence all four determinants, but itcan also be expressed as the sum of all other economicassets of the firm (Wayland and Cole 1997); Gupta,Lehmann, and Stuart (2004) also demonstrate this.

First, the acceleration of cash flows is affected by thespeed of buyer response to marketing efforts. Because ittakes less effort to persuade a satisfied customer (Keller1993) and because it is more likely that receivables turnoveris better for firms with satisfied customers, speed of cash

flow is positively affected. Second, there is also a relation-ship between customer satisfaction and levels of net cashflows. Marginal costs of sales and marketing are lower, asare the requirements for working capital and fixed invest-ments (Srivastava, Shervani, and Fahey 1998). In addition,revenue growth benefits from more repeat business. Grucaand Rego (2005) provide empirical evidence for this. Theyshow that increases in customer satisfaction lead to signifi-cant cash flow growth. Specifically, one point in customersatisfaction (measured by ACSI on a 0–100 scale) was asso-ciated with a 7% increase in cash flow. Third, Gruca andRego also find that the risk associated with future cashflows is reduced for firms with high customer satisfaction.

If the variability in cash flows is reduced, the cost of capitalgoes down as well, thus producing yet another source forstock price growth. Finally, the residual value of business isa function of the size, loyalty, and quality of the customerbase, all of which are obviously related to the satisfaction of this customer base (Srivastava, Shervani, and Fahey 1998).

Customer Satisfaction and MarketValue of Equity

In light of the evidence reported in the literature, it might beexpected that a significant relationship exists between mar-ket value of equity and ACSI. If customer satisfaction trulyis an economic asset that is not only left off the balancesheet but also not fully reflected by the recorded assets,there should be a relationship between ACSI scores andmarket capitalization. Following standard practice (Barthand McNichols 1994; Ittner and Larcker 1998; Landsman1986), the model we define in Equation 1 estimates theeffect of an identifiable, but intangible, asset on market cap-italization in a combined longitudinal cross-sectional set-ting, while controlling for accounting book values. In thiscase, we are interested in (1) whether customer satisfaction(ACSI) has a significant effect on market value of equity

and (2) the size of this effect when we control for the influ-ence of the recorded assets and liabilities. Thus:

(1) lnMVE = α + β1 lnBVA + β2 lnBVL + β3 lnACSI,

where MVE is the market value of equity, BVA is the book value of total assets, BVL is the book value of liabilities,and ACSI is the respective company score on the AmericanCustomer Satisfaction Index.

We obtained the data from 1994–2002 ACSI scores andCOMPUSTAT company book values for the same years;

there were a total of 601 observations. The mean value formarket value is $26 billion. For book value of assets andliabilities, the respective means are $23 billion and $15billion.

Table 1 reports the results of fitting Equation 1 by ordi-nary least squares. The regression is highly significant withan R-square of .70. The ACSI coefficient is significant andlarge. A 1% change in ACSI is associated with a 4.6%change in market value. The coefficients for assets and lia-bilities are also significant with the expected signs. Table 1also includes estimates without the ACSI variable: R-squaredrops to .61, and the negative coefficient for liabilitiesincreases. Thus, by omitting customer satisfaction in the

estimation of company market value, the negative impact of liabilities appears to be greater than it should be. This isalso consistent with the previous discussion that customersatisfaction alleviates cash flow volatility and reduces thecost of capital.

Investor ReactionWe offer the preceding results as empirical evidence infavor of the argument that customer satisfaction should beconsidered an economic asset beyond what is recognized onthe balance sheet. The results are also consistent with thefinding that customer satisfaction is associated with long-term shareholder value. However, they do not address

TABLE 1The Effect of ACSI on Market Value of Equity

Ln(Market Ln(MarketValue) Value)

ACSI (lnACSI) β1 4.592(.000)

Total assets (lnBVA) β2 1.943 2.039(.000) (.000)

Total liabilities (lnBVL) β3 –1.020 –1.157(.003) (.003)

Constant α –20.056 .235(.000) (.704)

N 601 601

R2 .70 .61

F (.000) (.000)

Notes: We estimated the models by including dummy variables (notshown) for years 1995 through 2002 (1994 was the refer-ence year); p values are in parentheses.

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 4/13

6 / Journal of Marketing, January 2006

whether ACSI scores provide information to investors (thatis not already known to them). How then do investors reactto news about customer satisfaction? Do they take advan-tage of customer satisfaction as a leading indicator of finan-cial performance, or do they fail to realize the potential of the information? Is the information already factored inshare prices? If, indeed, customer satisfaction is relevant tomarket valuation, according to efficient markets theory, newinformation about customer satisfaction fluctuations shouldbe instantly reflected in stock prices. That is, all else being

equal, investors should reward firms with increased marketcapitalization as news about the improved value of firms’customer relationships becomes available. Conversely, newsabout deteriorating customer relationships should have theopposite effect.

Such reasoning is in concert with financial valuationtheory in that customer relationships can be expressed interms of net present value (Blattberg and Deighton 1996;Hogan et al. 2002; Rust and Keiningham 1994; Venkatesanand Kumar 2004). In competitive markets, the value of sat-isfied customers should be worth more than the value of dissatisfied customers.

However, the picture is more complicated. There are

reasons for suggesting that investors may not react in a pre-dictable fashion, and there are circumstances in which stock prices drop as a result of news about increasing customersatisfaction. Although such a reaction might be at odds withhow capitalistic markets should function, consumer marketimperfections (which may be unknown) make it difficult toanticipate capital market reactions to customer satisfactionnews. First, investors may react negatively to news aboutrising customer satisfaction if they believe that the firm isgiving away too much surplus to the buyers. The aggregatesurplus that consumers receive from goods and services is ameasure of consumer welfare, but the difference betweenthe maximum price a buyer is willing to pay and the actual

price is also something that investors may want to capture.Investors would be more likely to consider an increase inconsumer surplus in a negative light if the buyer’s switchingcosts were significant, if there was a high degree of productdifferentiation, or if there was some level of monopolypower.

Second, investors may also take an unkind view of improvements in customer satisfaction for firms thatalready have substantial leads over their competition. If cus-tomers of competing firms were much less satisfied, themarginal return of improving customer satisfaction furthermight be called into question. Certainly, it would be diffi-cult to ignore economic laws of diminishing returns for theinvestment in any economic asset, regardless of its status on

the balance sheet.Third, and related to the preceding two points, the mar-

ginal cost of improving customer satisfaction may be toohigh. This is particularly relevant for services, especiallythose that are labor intensive. For example, it has beenshown (Anderson, Fornell, and Rust 1997) that productivityand customer satisfaction are not always compatible in theservice sector. Improved customer satisfaction may come atthe expense of productivity, and vice versa. Such a trade-off between productivity and customer satisfaction may also

contribute to unfavorable market reactions to news aboutcustomer satisfaction improvements.

Fourth, there is the possibility of a “reverse causalityeffect.” Customer defection can have a positive effect onaverage customer satisfaction simply because the departingcustomers were the most dissatisfied. Customers whoremain are less likely to be as discontented. Instead of ben-efiting from improved satisfaction, the company simplyretains a smaller group of (somewhat more satisfied) cus-tomers, but often with reduced sales and profits as a result.

Note that this effect is not the result of consumer marketimperfections. Indeed, it is more likely to occur in fluidmarkets with low switching barriers and no monopolypower.

Fifth, issues of timing and expectations complicate thematter further. The ACSI measures each company once ayear. Although the measurement is cumulative in the sensethat it aims to capture all relevant customer experience(with the product or service) to date, it is possible forchanges in customer satisfaction to occur and to have aneffect on buyer behavior (with implications on revenues andprofits) in periods between measurements. It is also difficultto ascertain market expectations about customer satisfac-

tion. A firm’s improved ACSI scores may be viewed as neg-ative if the firm was expected to show a greater degree of improvement, and vice versa. Sources of such expectationsmay be difficult to identify; they may include corporateannouncements about additional investments in consumerservice, the hiring of more frontline personnel, investmentsin information technology and customer relationship man-agement systems (Krishnan et al. 1999; Mithas, Krishnan,and Fornell 2005a, b; Prahalad, Krishnan, and Mithas 2002;Rai, Patnayakuni, and Patnayakuni 2006; Sambamurthy,Bharadwaj, and Grover 2003; Srinivasan and Moorman2005), and a host of things that may affect customersatisfaction.

For all these reasons, it is not easy to predict stock mar-ket reactions to news about customer satisfaction for indi-vidual companies. It would not be enough to appeal to cap-italistic market theory without consideration of anassortment of market conditions. Even if the relevant char-acteristics were observed and properly assessed, the effectmay be confounded by the shape of the satisfactionresponse curve, by the firm’s location on the curve, or bythe reverse causation phenomenon. Thus, even if investorsdo not react to news about customer satisfaction, shareprices may still be unbiased. Only if it is possible to useACSI information to discover mispriced stocks consistentlyover time and invest accordingly (and thus beat the market)can the question about possible pricing bias be addressed.

Accordingly, we conduct both an event study and portfoliostudies. We begin with the event study.

We estimate the rate of return on stock price of firm j onday t with the following market model:

(2) R jt = α j + β j Rmt + ε jt,

where R jt is the rate of return on the common stock of the jth firm on day t, Rmt is the market rate of return using theStandard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 composite index on day t, α j

is an intercept, β j is a slope parameter that measures the

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 5/13

Customer Satisfaction and Stock Prices / 7

2Although ACSI has measured customer satisfaction since1994, before the second quarter of 1999, the results were pub-lished once a year in Fortune magazine, making it difficult to pin-point the event date because readers received the magazine on dif-ferent dates. For example, Ittner and Larcker’s (1998) study used amuch longer event window (five and ten days) in their analysis of the effect of the Fortune publication.

sensitivity of R jt to the market index, and ε jt is a disturbanceterm with the usual ordinary least squares properties. TheS&P 500 is a capitalization weighted index based on abroad cross-section of the market and has been used in sev-eral previous event studies (MacKinlay 1997).

We use the market model (Equation 2) to estimate theabnormal return for the common stock of firm j on day t,such that

(3) AR jt = R jt – (α j + β j Rmt).

On the basis of recommended guidelines and commonlyused practice, we specified the length of the estimationperiod as 255 days, ending 46 days before the event date(Cowan 2003; McWilliams and Siegel 1997).

We averaged daily abnormal returns using the closingprice at the day of the release over the sample of N firms toyield cumulative abnormal returns:

where T1 and T2 correspond to the first and last days of the

event period.Because the sampling distribution of abnormal returns

tends to be skewed and leptokurtic (Brown and Warner1985; Corrado 1989; Lyon, Barber, and Tsai 1999;McWilliams and Siegel 1997), we used bootstrapping forall significance tests. Use of bootstrapped test statistics pro-vide a more robust assessment of the statistical significanceof the results of the event study and is becoming increas-ingly common in academic studies (Chatterjee, Richardson,and Zmud 2001).

It is well known that event studies benefit considerablyfrom a precise definition of the event period (Barclay andLitzenberger 1988; Brown and Warner 1985; Dyckman,

Philbrick, and Jens 1984). As for the ACSI, there is an exactannouncement day. Thus, we specify a one-day eventperiod. A short event period leads to more efficient estima-tion because it reduces the possibility of other factorsaffecting the returns. It also increases the power of the sta-tistical tests.

As we indicated previously, we defined the event as theACSI announcement for a firm as (simultaneously) pub-lished in The Wall Street Journal and on the ACSI Web site.Because the The Wall Street Journal is a daily publication, itseems reasonable to consider the day the ACSI announce-ment is published in The Wall Street Journal as the daywhen “the event” occurs. The included events range from

the second quarter of 1999 to the third quarter of 2002.2

Following recommended practice (MacKinlay 1997),we set up controls so that the customer satisfaction news

( ) ,41 2

1

2

1CAR

AR

NT T

t T

T

jt

j

N

=

==

∑∑

3Although it seems unlikely that the ACSI information wouldtrickle out slowly or that investors would simply wait before acting

on the information, we also calculated cumulative abnormalreturns for a 5-day window following the release date. Again, thenull hypothesis of zero abnormal returns cannot be rejected. Afinal test checks for the possibility of prior leakage of information.The ACSI results were routinely provided under embargo to thepublic relations and market research units of corporate subscribers

would not be confounded with other news items over thesame period. We collected all firm-related news items fivecalendar days before and after the event date from leadingsources: PR Newswire, Dow Jones, and Business Wire. Weexcluded from the analysis events with announcementsregarding mergers and acquisitions, spin-offs, stock splits,chief executive officer and chief financial officer changes,layoffs, restructurings, earnings announcements, and law-suits. In total, after we eliminated the events with con-founded news items during the event windows, the data

consisted of 161 events for 89 companies for which stock-trading data were available for the study period. For manu-facturing firms, there were 48 events of rising ACSI scores;for service firms, the corresponding number was 32. Therewere 41 events with decline in ACSI for manufacturing and40 for services. The results appear in Table 2.

Although the combined samples for manufacturing andservices changed in the direction of higher stock prices forfirms with an increase in ACSI and lower prices for firmswith a decrease in ACSI, these effects are too weak to bedistinguished from chance variation. The results for servicefirms are also contradictory; that is, share prices increasedregardless of the direction of the change in ACSI.

These results are fairly consistent with the findings of Ittner and Larcker (1998). They used a longer event windowof five days and found no significant effects of ACSI news.For a ten-day window, they reported close to significant (atthe 10% level) abnormal returns but only after they deletedoutliers (still 97%–98% of the variance in the abnormalreturns remained unexplained). Note that Ittner and Larckerwere forced to use cross-sectional analysis (because of thelimited amount of data available at the time), and thus theirresults cannot be used to test the effect of ACSI on changesin stock prices (Lambert 1998).3

TABLE 2

Abnormal Returns For ACSI NewsAnnouncements

Event DayType of AbnormalNews Firm Type N Returns

Increase Manufacturing 80 .34in ACSI and services

Manufacturing 48 .01Services 32 .85

Decrease Manufacturing 81 –.17in ACSI and services

Manufacturing 41 –.54Services 40 .20

Notes: None of the abnormal returns are significant at the 5% levelbased on nonparametric bootstrapped tests (two tailed).

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 6/13

8 / Journal of Marketing, January 2006

and to The Wall Street Journal about two weeks before the release.That corresponds to 10 additional trading days before the event.Again, the results are not significant. The results of 5-day and 15-day analyses appear in the Appendix.

Portfolio StudiesThe finding that news about customer satisfaction does notmove stock prices, even though customer satisfaction is sta-tistically significant with respect to market valuation, is notnecessarily contradictory to efficient markets theory. Itwould still be possible that stock prices fully and quicklyreflect all available information. It is also possible that firmswith highly satisfied customers generate higher profits.Under efficient markets theory, however, it would not be

possible to develop trading strategies based on ACSI infor-mation that consistently earn excess returns.As a way to test this, we consider two stock portfolios

based on ACSI data. The first is a hypothetical paper portfo-lio with simple trading rules. The second is a real-worldportfolio. Both tests have pros and cons. However, theircombination leads to more powerful analyses. The majoradvantage of the paper portfolio is that the trading rules areclear and explicit. In addition to there being no theoreticalbasis for simulating various permutations of the tradingstrategy, its major disadvantage is that it is hypothetical andback tested with perfect hindsight.

For the real-world portfolio, these advantages and dis-advantages are reversed. Actual trading involves many

details regarding timing, size of investments, number of holdings, rebalancing, and so forth, that are not always pre-cisely determined by static and explicit decision rules. Inmany ways, the situation is similar to case studies of orga-nizations for which theoretical specificity must give way torealism. Yet this is also the benefit of a real-world portfolio:It presents authentic investments and actual results.

Most important, however, paper portfolio and the actualportfolio share a critical aspect: Both rely solely on ACSIdata. No other type of data or additional information wasconsidered in any of the investment decisions. Althoughdetails may vary between the portfolios, and assuming anabsence of contemporaneous underlying share price deter-

minants that covary with ACSI (we discuss this further sub-sequently), it would be difficult to attribute the results tosources other than customer satisfaction.

Because the market does not immediately respond tochanges in ACSI, it seems reasonable to base the strategyon both levels (because they do not appear to be fullyimpounded in the market price) and changes (because theydo not appear at all to be impounded in the market price).To have a diversified portfolio of reasonable size, weselected firms in the top 20% of ACSI (relative to theircompetition). In line with Jones and Sasser (1995) andIttner and Larcker (1998), who find that low levels of cus-tomer satisfaction appear to have less of an impact, we also

made the selection conditional on the requirement of beingabove the ACSI national average.Because ACSI scores for each individual firm are

updated once a year, we purchased shares (using the closingprice) the day the ACSI results were announced and heldthem for a year or longer. If we picked a stock the first year,

we examined its inclusion in the portfolio again the follow-ing year. If it met the criteria of being in the top 20% andabove the national (average) ACSI level, we held it foranother year and then subjected it to the same test. If itfailed the criteria, we sold it. We applied the same principlefor all stocks. If we did not pick a stock the first year, wereexamined it for inclusion the next year, and so on. Thistrading strategy led to a portfolio of 20 companies in 1997and 20 in 1998, and there were 26 companies at the conclu-sion of the test on May 21, 2003.

Between February 18, 1997, and May 21, 2003, aperiod when the stock market had both ups and downs, theportfolio generated a cumulative return of 40% (with divi-dends and transaction costs excluded but after stock splits,if any, were adjusted). It outperformed the Dow JonesIndustrial Average (DJIA) by 93%, the S&P 500 by 201%,and NASDAQ by 335%. Figures 1–3 show the cumulativereturns over time.

The results suggest that customer satisfaction pays off in up-markets and down-markets. When the stock marketgrew, the stock prices of many firms with highly satisfiedcustomers grew even more. The only exception occurred atthe peak of the stock market bubble in 1999, when NAS-

DAQ and the S&P 500 generated short-lived, but higher,returns. When the stock market dropped in value, the stock prices of firms with highly satisfied customers seemed tohave benefited from some degree of insulation.

Although the trading rules barred all informationbeyond ACSI, could there be competing explanations forthe findings? We examine the possibilities. First, andregardless of whether efficient markets theory holds, it isdifficult to beat the market. Most professional stock pickersdo not, and the chance probability of consistent excessreturns is minute. Second, there are theoretical underpin-nings behind these returns that are bolstered by empirical

–10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

ACSI

DJIA

20032002200120001999199819971996

DJIA = 21%

Total

cumulative

return

ACSI = 40%

aFebruary 18, 1997, through May 21, 2003.

FIGURE 1Cumulative Returns: ACSI Top 20% Versus DJIA

(1997–2003)a

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 7/13

Customer Satisfaction and Stock Prices / 9

–10%

0%

10%

20%

30%40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

ACSI

S&P 500

20032002200120001999199819971996

S&P 500 =

13%

Total

cumulative

return

ACSI = 40%

aFebruary 18, 1997, through May 21, 2003.

FIGURE 2

Cumulative Returns: ACSI Top 20% Versus S&P500 (1997–2003)a

–10%0%

10%20%30%40%50%60%70%80%90%

100%110%120%130%140%

150%160%170%180%190%200%

ACSI

NASDAQ

20032002200120001999199819971996

NASDAQ =

9%

Total

cumulative

return

ACSI = 40%

aFebruary 18, 1997, through May 21, 2003.

FIGURE 3

Cumulative Returns: ACSI Top 20% VersusNASDAQ (1997–2003)a

findings in the marketing literature. Third, the abnormalreturns are not due to compensation for risk. The beta risk associated with the portfolio is .78 and thus is substantiallyless than market.4 Fourth, there is no known ACSI covariatethat accounts for the results. Firms are included in ACSI onthe basis of size (Fornell et al. 1996), and the ACSI aggre-gate should approximately mirror large cap indexes (e.g.,DJIA). There is no reason to suspect that the top 20% of ACSI firms would have the same performance as the bot-tom 80%. To verify this empirically, we collected stock price data for all ACSI firms. The cumulative return for the

bottom 80% portfolio was 20.4%, which is virtually identi-cal to that of the DJIA (21%), thus ruling out selection cri-teria as a covariate of the stock performance. Because book-to-market ratios are sometimes mentioned as possiblepredictors of long-term abnormal stock returns (Fama andFrench 1992), we compared these ratios as well. For the top20%, the book-to-market ratio was .41 for the full timeperiod. The corresponding ratio for the bottom 80% was.42. Finally, we examined the “size effect.” It has beenshown that smaller firms’ stocks tend to produce higherreturns (Banz 1981; Bernard and Thomas 1989; Reinganum1981). Are the top 20% of ACSI firms smaller than the bot-tom 80%? Consistent with the results in Table 1, the oppo-site is true. The average revenue for the top 20% of firms is$37.8 billion, compared with $26.4 billion for the bottom80%.

Overall, these results are noteworthy because they sug-gest a trading strategy with high returns and low risk, basedon theory and findings not in finance or economics but

4The beta values are relative to the S&P 500 over the entire lifeof the portfolio. On a year-by-year basis, the betas are .72 (1997),.75 (1998), .74 (1999), .75 (2000), .76 (2001), .81 (2002), and .93(2003).

rather in the marketing literature. Because of the magnitudeof the abnormal returns, the findings are perhaps even moreremarkable considering that most brokerage firms had neg-ative abnormal returns on their stock recommendations

between 1997 and 2001 (McGeehan 2001). Nonetheless, aword of caution is warranted. The results refer to a paperportfolio that is back tested. As with all such testing, thereare obvious limitations. In hindsight, it may not be that dif-ficult to find a successful trading strategy. In defense of theresults, however, we note that the trading strategy used wasextraordinarily simple and straightforward.

However, not all individual trades were good ones.Gateway computers is a case in point. Stock was purchasedon August 21, 2000, because the company had an ACSIscore of 78, which was in the top 20% of its industry andabove the national average. Stock was sold on August 20,2001, because the company dropped out of the top 20%.

Over that period of time, the company’s stock price fell by84% because consumer demand for personal computersdeclined sharply. As we discussed previously, there may bemany reasons that the trading strategy may not work foreach individual company all the time. In addition, there isno reason to believe that high customer satisfaction willprovide full stock market insulation if primary consumerdemand falters. It may dampen the fall to some degree, butindustry demand is affected by many other factors. How-ever, from a diversified portfolio, negative industry distur-bances should be counterbalanced by positive ones. To

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 8/13

10 / Journal of Marketing, January 2006

–30%

–20%

–10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

S&P 500

ACSI Portfolio

20042003200220012000

–8%

–12%

6%

–13%

–5%

–23%

36%

26%

32%

9%

aApril 11, 2000, through December 31, 2004.

FIGURE 4

Yearly Performance of ACSI Portfolio and S&P 500(2000–2004)a

5For discussions on this type of elasticity, see Fornell (1992)and Anderson, Fornell, and Mazvancheryl (2004).

6The ACSI includes many utilities. To compensate, each utilityin the portfolio received only half of the dollar amount invested innonutility companies.

7Accordingly, some trades were executed subsequent to the

ACSI release date (approximately 70%), and some were executedbefore that date. Because there was no announcement event effect,the positive returns were not helped by this timing. On the con-trary, they were somewhat handicapped. The cumulative return forthe portfolio for all the event days (using the closing price of theday of the ACSI release), through February 2003, was –1.6%. TheDJIA and S&P 500 did somewhat better at +.5% and +.6%,respectively. All trades subsequent to February 2003 were exe-cuted after the ACSI release.

8The 2000 results do not represent the full year. They reflect thestarting date of the portfolio (April 11, 2000).

some extent, the large losses made on Gateway in oneperiod were compensated by a 47% gain in another period(1999–2000), as well as Dell Computer’s return of 50% in1998–1999 and the very large rise of the Wal-Mart (96% in1998–1999) and Southwest Airlines (96% in 1998–1999)stocks.

Our final analysis goes from hypothetical paper tradingto an actual stock portfolio of ACSI companies. Thus, itavoids the usual limitations of back testing and providesadditional evidence about the strength of the relationship

between customer satisfaction and stock price. As before,we considered no other data but ACSI data in the invest-ment decisions. We took both long and short positions andbased trading decisions on ACSI levels, changes, and satis-faction elasticity of demand.5 The portfolio took long posi-tions in firms with high (above competition) and increasing(by two points or more) ACSI scores and also when theACSI–customer retention (elasticity) estimate was aboveaverage. It took short positions when scores were low(lower than any competitor) and deteriorating (by twopoints or more). The short positions were generally smalland ranged over time from 0% to 20% of the portfolio. Weheld these positions for a one-year period or more. We bal-

anced the portfolio weighting with approximately the samedollar amount for each company at the starting point butalso with consideration given to industry representation.6

We periodically rebalanced to dollar equalize the positions,and we executed trades throughout the year without atten-tion to the date of the ACSI release.7 We reinvested divi-dends and included transaction costs. Trading began inApril 2000, at a time just before the burst of the stock bub-ble from which the market, as of the end of 2004, has notyet recovered.

The portfolio generated impressive positive returns. Aswe show in Figure 4, it outperformed the S&P 500 each andevery year during the five years since its inception, often by

a considerable margin. The smallest gain relative to marketwas in 2000 when the S&P dropped by 12% and the ACSIportfolio dropped by 8%.8 In the following year, the portfo-lio gained 6%, whereas the S&P continued to fall by 13%.

With the exception of 2002, when the S&P fell by 23% andthe ACSI portfolio fell by 5%, there have been large gains:36% in 2003 (versus 26% for the S&P) and 32% in 2004(versus 9% for the S&P). On a cumulative basis (Figure 5),

–50%

–40%

–30%

–20%

–10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

2001 2002 2003 2004

ACSI

+75%

DJIA

–5%

S&P

500

–19%

aApril 11, 2000, through December 31, 2004.

FIGURE 5ACSI Portfolio Versus DJIA and S&P 500

(2000–2004)a

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 9/13

Customer Satisfaction and Stock Prices / 11

9Because the portfolio includes reinvested dividends and trans-action costs, the comparison with market indexes is not exactly“apples to apples,” but the gains relative to market are muchgreater than the net effects from dividends and transaction costs.For example, with dividends and transaction costs included, theaverage diversified stock portfolio rose only 1% according to Lip-per Research over the same time period.

10The year-to-year ACSI portfolio betas relative to the DJIA are.87 (2000), .67 (2001), .74 (2002), .82 (2002), and .84 (2004). Theyear-to-year ACSI portfolio betas relative to the S&P 500 are .83(2000), .73 (2001), .72 (2002), .82 (2003), and .87 (2004).

the ACSI portfolio gained 75%, compared with a loss of 19% for the S&P 500. The DJIA did slightly better at –4%.9

As with the previous portfolio study, these returns arenot associated with higher risk. The betas for the real-worldportfolio are equivalent to the paper portfolio. The meanbeta risk for all years was .77 relative to the S&P and .76relative to the DJIA. On an annual basis, the beta risk of theportfolio was consistently below market.10

Similar to the hypothetical paper version, share pricesfor firms that did well on ACSI rose faster than the market

and dropped at a slower rate. However, short selling pro-duced weaker returns (less than 3% of the total), implyingasymmetric impacts from high versus low customer satis-faction. However, it would be premature to conclude on thebasis of this finding alone that the market rewards high cus-tomer satisfaction more than it punishes low satisfaction.Additional studies would be necessary to draw such aconclusion.

DiscussionBy any standard, the results of the studies we report hereinare extraordinary. Not only do they show that investments

based on customer satisfaction produce sizable excessreturns, but they also upset the basic financial principle thatassets producing high returns carry high risk. The price of any financial asset is determined by the current value of thefuture cash payments it generates, discounted to compen-sate for risk and cost of capital. The economic value of sat-isfied customers seems to be systematically undervalued,even though these customers generate substantial net cashflows with low volatility. Firms that do better than theircompetition in terms of satisfying customers (as measuredby ACSI) generate superior returns at lower systematic risk.Similar security mispricings, but on a much lower scale,have been found in related situations with respect to qualityawards announcements (Hendricks and Singhal 2001) andmarketing investments (Penman and Zhang 2001), but mostdiscoveries of security mispricings point to “overpricing”(Shiller 2000). Under the assumption of efficient marketstheory, if information about customer satisfaction is rele-vant to a company’s future economic performance, it shouldbe factored into the company’s stock price such that itwould not be possible to earn economic profits by tradingon this information. Yet we show that this is indeed possi-ble. However, this does not imply a wholesale rejection of efficient markets theory. There have been many documentedanomalies over the years (e.g., the January effect, the small-

11This is not to suggest that all securities analysts completelyignore customer satisfaction. For example, Merrill Lynch andMorgan Stanley have written reports on it, and in general, analystsattribute the surge in Apple’s stock price in late 2004 to anincrease in customer satisfaction.

firm effect, the Monday effect, the post-earnings-announcement drift). Most of them have since disappeared.Whether that will be the case with the customer satisfactioneffect is yet to be determined, but it is less likely because,with the exception of the public release of ACSI and con-trary to the January effect and others, the information is notcostless and requires more sophisticated measurement tech-nology than firms typically use today (Ittner and Larcker2003). Because investments based on customer satisfactionmay not be publicly known, it would also be much more

difficult to verify a possible demise. According to Gupta,Lehmann, and Stuart (2004), financial analysts have yet togive more than scant attention to off-balance-sheet assets,even though these assets may be key determinants of afirm’s market value. By using a discounted cash flow analy-sis for estimating the value of customer relationships,Gupta, Lehmann, and Stuart find that some companies werepotentially mispriced, whereas others were not.

Taken as a whole, the conclusion from these analyses isthat though firms with highly satisfied customers usuallygenerate positive abnormal returns, news about changes incustomer satisfaction does not have an effect on stock prices. In other words, the primary thesis behind capitalist

markets and marketing theory is borne out, but not withoutreservations about efficient (equity) markets theory. Specif-ically, there seem to be imperfections with respect to thetime it takes for stock markets to reward firms that do wellby their customers and to punish firms that do not. In thewake of accounting scandals, the bursting of the stock mar-ket bubble, and the continued weakening of the relationshipbetween balance sheet assets and future income, it would bein the interest of securities research to pay closer attentionto customer satisfaction and the strength of customer rela-tionships. For marketing managers, it is clear that the costof managing customer relationships and the cash flows theyproduce is fundamental to value creation.

The principal short-term impact of the findings may beto boost security analysts’demand for customer satisfactioninformation. If history is a guide, however, it will be diffi-cult for analysts to separate the “good” from the “bad” andthe relevant from the irrelevant when it comes to this typeof information. This will be a serious challenge becauserecent experience with valuing intangible assets did not turnout well. Just before the stock market bubble burst, WallStreet seemed enamored with customer metrics, most of which had dubious connections to economic value creationand large losses in shareholder wealth as a result. Thus, amore prudent approach might be expected this time, butappropriate prudence does not suggest eschewing customermetrics altogether, which more or less seems to be the case

for securities research today.11 Rather, the quality of mea-surement and economic relevance should dictate how thesemetrics should best be used. For example, although cus-tomer satisfaction is strongly related to economic value

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 10/13

12 / Journal of Marketing, January 2006

creation and the (collective) customer may have informa-tion relevant to the financial prospects of the firm beforeinvestors do, this cannot be leveraged if measurement isflawed and unable to extract the information. Ittner and Lar-cker (2003) find that most companies’ measurementmethodologies for customer satisfaction are “mindless,”misleading, and too primitive to be useful. This state of affairs is unlikely to change unless shareholders, corporateboards, and investors put more pressure on companies toaccount for intangible assets more effectively. If accounting

were to include information about the health of the firm’scustomer relationships, investors would have a better under-standing of the link between the firm’s assets and its capac-ity to generate shareholder wealth, and managers would becompensated accordingly. Corporate governance wouldbenefit as well.

If investors were to use capital more expediently toencourage firms to strive for higher levels of customer satis-faction and better quality of measurement, there would bemany beneficiaries. Consumers would be better off. As con-sumer and equity markets become more synchronized, their joint influence may contribute to less misallocation of capi-tal, quicker deflation of stock market bubbles (see Figures

1–3), fewer cases of security mispricings, and a better func-tioning of markets in general.

Although investors fail to realize the relevance of ACSInews and equity markets exhibit imperfections in thisregard, the results of this study affirm the workings of freecapitalistic markets with respect to the relationship betweenconsumer utility and the flow of investment capital.

Although it takes a while for equity markets and consumermarkets to exercise their joint power, the finding that cus-tomer satisfaction and stock prices eventually movetogether suggests that most markets get it right in the longrun. They apparently offer meaningful consumer choice,and short-term fluctuations and other exceptions notwith-standing, sellers may take comfort that they will (eventu-ally) be rewarded for treating customers well and that theyrisk punishment for treating customers poorly.

REFERENCESAaker, David A. and Robert Jacobson (1994), “The Financial

Information Content of Perceived Quality,” Journal of Market-

ing Research, 31 (May), 191–201.Ambler, Tim, C.B. Bhattacharya, Julie Edell, Kevin Lane Keller,Katherine N. Lemon, and Vikas Mittal (2002), “Relating Brandand Customer Perspectives on Marketing Management,” Jour-nal of Service Research, 5 (1), 13–25.

Anderson, Eugene W. (1996), “Customer Satisfaction and PriceTolerance,” Marketing Letters, 7 (3), 19–30.

———, Claes Fornell, and Donald R. Lehmann (1994), “Cus-tomer Satisfaction, Market Share, and Profitability: Findingsfrom Sweden,” Journal of Marketing, 58 (July), 53–66.

———, ———, and Sanal K. Mazvancheryl (2004), “CustomerSatisfaction and Shareholder Value,” Journal of Marketing, 68(October), 172–85.

———, ———, and Roland T. Rust (1997), “Customer Satisfac-tion, Productivity, and Profitability: Differences BetweenGoods and Services,” Marketing Science, 16 (2), 129–45.

——— and Mary W. Sullivan (1993), “The Antecedents and Con-sequences of Customer Satisfaction for Firms,” Marketing Sci-ence, 12 (2), 125–43.

Banz, R. (1981), “The Relationship Between Return and MarketValue of Common Stocks,” Journal of Financial Economics, 9(March), 3–18.

Barclay, M.J. and R.H. Litzenberger (1988), “AnnouncementEffects of New Equity Issues and Use of Intraday Price Data,”

Journal of Financial Economics, 21 (1), 71–99.Barth, M.E. and M.E. McNichols (1994), “Estimation and Market

Valuation of Environmental Liabilities Relating to Superfund

Sites,” Journal of Accounting Research, 32 (Special Issue),177–209.

Bell, David, John Deighton, Werner J. Reinartz, Ronald T. Rust,and Gordon Swartz (2002), “Seven Barriers to CustomerEquity Management,” Journal of Service Research, 5 (1),77–85.

Berger, Paul D., Ruth N. Bolton, Douglas Bowman, Elten Briggs,V. Kumar, A. Parasuraman, and Creed Terry (2002), “Market-ing Actions and the Value of Customer Assets: A Framework for Customer Asset Management,” Journal of Service

Research, 5 (1), 39–54.Bernard, V.L. and J.K. Thomas (1989), “Post-Earnings Announce-

ment Drift: Delayed Price Response or Risk Premium,” Jour-

nal of Accounting Research, 27, 1–36.Blattberg, Robert C. and John Deighton (1996), “Manage Market-

ing by the Customer Equity Test,” Harvard Business Review,74 (July–August), 136–44.

Bolton, Ruth N. (1998), “A Dynamic Model of the Duration of theCustomer’s Relationship with a Continuous Service Provider:The Role of Satisfaction,” Marketing Science, 17 (1), 45–65.

———, P.K. Kannan, and Matthew D. Bramlett (2000), “Implica-tions of Loyalty Program Membership and Service Experi-ences for Customer Retention and Value,” Journal of the Acad-

emy of Marketing Science, 28 (1), 95–108.———, Katherine N. Lemon, and Peter C. Verhoef (2004), “The

Theoretical Underpinnings of Customer Asset Management: AFramework and Propositions for Future Research,” Journal of

the Academy of Marketing Science, 32 (July), 271–92.

APPENDIX

Five and Fifteen Days of Cumulative AbnormalReturns (CAR) for ACSI News Announcements

CAR CARType of 5-Day 15-DayNews Firm Type N Window Window

Increase Manufacturing 80 1.85 –.95in ACSI and services

Manufacturing 48 .98 1.23Services 32 3.15 –4.22

Decrease Manufacturingin ACSI and services 81 –.22 –1.65

Manufacturing 41 –.78 –2.72Services 40 .36 –.55

Notes: None of the cumulative abnormal returns are significant atthe 5% level based on nonparametric bootstrapped tests(two tailed).

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 11/13

Customer Satisfaction and Stock Prices / 13

Brown, Stephen J. and Jerold B. Warner (1985), “Using DailyStock Returns: The Case of Event Studies,” Journal of Finan-cial Economics, 14 (1), 3–31.

Bursk, Edward C. (1966), “View Your Customers as Investments,” Harvard Business Review, 44 (May–June), 91–94.

Capon, Noel, John U. Farley, and Scott Hoenig (1990), “Determi-nants of Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis,” Manage-ment Science, 36 (10), 1143–59.

Chatterjee, Debabroto, Vernon J. Richardson, and Robert W. Zmud(2001), “Examining the Shareholder Wealth Effects of Announcements of Newly Created C.I.O. Positions,” MIS

Quarterly, 25 (1), 43–70.Corrado, Charles J. (1989), “A Nonparametric Test for AbnormalSecurity-Price Performance in Event Studies,” Journal of Financial Economics, 23 (2), 385–95.

Cowan, Arnold R. (2003), Eventus 7.5 User’s Guide. Ames, IA:Cowan Research LC.

Dyckman, T., D. Philbrick, and J.S. Jens (1984), “A Comparisonof Event Study Methodologies Using Daily Stock Returns: ASimulation Approach,” Journal of Accounting Research, 22(Supplement), 1–30.

Fama, Eugene F. and Kenneth R. French (1992), “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns,” Journal of Finance, 47(2), 427–65.

Fornell, Claes (1992), “A National Customer Satisfaction Barome-ter: The Swedish Experience,” Journal of Marketing, 56 (Janu-ary), 6–22.

——— (1995), “The Quality of Economic Output: EmpiricalGeneralizations About Its Distribution and Relationship toMarket Share,” Marketing Science, 14 (3), G203–G211.

——— (2001), “The Science of Satisfaction,” Harvard Business Review, 79 (March), 120–21.

———, Michael D. Johnson, Eugene W. Anderson, Jaesung Cha,and Barbara Everitt Bryant (1996), “The American CustomerSatisfaction Index: Nature, Purpose, and Findings,” Journal of

Marketing, 60 (October), 7–18.——— and Birger Wernerfelt (1987), “Defensive Marketing Strat-

egy by Customer Complaint Management: A TheoreticalAnalysis,” Journal of Marketing Research, 24 (November),337–46.

——— and ——— (1988), “A Model for Customer ComplaintManagement,” Marketing Science, 7 (Summer), 271–86.

Garvin, David A. (1988), Managing Quality: The Strategic and Competitive Edge. New York: The Free Press.

Gruca, Thomas and Lopo Rego (2005), “Customer Satisfaction,Cash Flow, and Shareholder Value,” Journal of Marketing, 69(July), 115–30.

Gupta, Sunil, Donald R. Lehmann, and Jennifer Ames Stuart(2004), “Valuing Customers,” Journal of Marketing Research,41 (February), 7–18.

Hendricks, Kevin B. and Vinod R. Singhal (2001), “The Long RunStock Price Performance of Firms with Effective TQM Pro-grams,” Management Science, 47 (3), 359–68.

Heskett, J.L., W.E. Sasser Jr., and L.A. Schlesinger (1997), TheService Profit Chain: How Leading Companies Link Profit and Growth to Loyalty, Satisfaction and Value. New York: The FreePress.

Hogan, John E., Donald R. Lehmann, Maria Merino, Rajendra K.Srivastava, Jacquelyn S. Thomas, and Peter C. Verhoef (2002),“Linking Customer Assets to Financial Performance,” Journalof Service Research, 5 (1), 26–38.

———, Katherine N. Lemon, and Ronald T. Rust (2002), “Cus-tomer Equity Management: Charting New Directions for theFuture of Marketing,” Journal of Service Research, 5 (1), 4–12.

Ittner, C.D. and D.F. Larcker (1996), “Measuring the Impact of Quality Initiatives on Firm Financial Performance,” in

Advances in the Management of Organizational Quality, Vol.1, Soumen Ghosh and Donald Fedor, eds. Greenwich, CT: JAIPress.

——— and ——— (1998), “Are Nonfinancial Measures LeadingIndicators of Financial Performance? An Analysis of CustomerSatisfaction,” Journal of Accounting Research, 36 (Supple-ment), 1–35.

——— and ——— (2003), “Coming Up Short on Non-FinancialPerformance Measurement,” Harvard Business Review,(November), 88–95.

Jackson, Barbara Bund (1985), Winning and Keeping Industrial

Customers: The Dynamics of Customer Relationships. Lexing-ton, MA: Lexington Books.

Jones, Thomas O. and W. Earl Sasser (1995), “Why Satisfied Cus-

tomers Defect,” Harvard Business Review, 73(November–December), 88–100.

Keller, Kevin L. (1993), “Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Man-aging Customer-Based Brand Equity,” Journal of Marketing,57 (January), 1–22.

Krishnan, M.S., Venkat Ramaswamy, Mary C. Meyer, and PaulDamien (1999), “Customer Satisfaction for Financial Services:The Role of Products, Services, and Information Technology,”

Management Science, 45 (9), 1194–1209.Lambert, Richard A. (1998), “Customer Satisfaction and Future

Financial Performance: Discussion of ‘Are Nonfinancial Mea-sures Leading Indicators of Financial Performance? An Empir-ical Analysis of Customer Satisfaction,’” Journal of Account-

ing Research, 36 (Supplement), 37–46.Landsman, W. (1986), “An Empirical Investigation of Pension

Fund Property Rights,” Accounting Review, 61 (4), 662–91.Lyon, John D., Brad M. Barber, and Chih-Ling Tsai (1999),

“Improved Methods for Tests of Long-Run Abnormal Stock Returns,” Journal of Finance, 54 (1), 165–201.

MacKinlay, A. Craig (1997), “Event Studies in Economics andFinance,” Journal of Economic Literature, 35 (1), 13–39.

McGeehan, Patrick (2001), “Market Place: Study QuestionsAdvice from Brokerage Firms,” The New York Times, (May29), C4.

McWilliams, Abagail and Donald Siegel (1997), “Event Studies inManagement Research: Theoretical and Empirical Issues,”

Academy of Management Journal, 40 (3), 626–57.Mithas, Sunil, Joni L. Jones, and Will Mitchell (2004), “Determi-

nants of Governance Choice in Business-to-Business Elec-tronic Markets: An Empirical Analysis,” working paper, Ross

School of Business, University of Michigan.———, M.S. Krishnan, and Claes Fornell (2005a), “Effect of Information Technology Investments on Customer Satisfaction:Theory and Evidence,” working paper, Ross School of Busi-ness, University of Michigan.

———, ———, and ——— (2005b), “Why Do Customer Rela-tionship Management Applications Affect Customer Satisfac-tion?” Journal of Marketing, 69 (October), 201–209.

Naumann, Earl and Steven H. Hoisington (2001), Customer Cen-tered Six Sigma: Linking Customers, Process Improvement,

and Financial Results. Milwaukee: ASQ Quality Press.Penman, Stephen H. and Xiao-Jun Zhang (2001), “Accounting

Conservatism, the Quality of Earnings, and Stock Returns,”The Accounting Review, 77 (2), 237–64.

Prahalad, C.K., M.S. Krishnan, and Sunil Mithas (2002), “Cus-

tomer Relationships: The Technology Customer Disconnect,”Optimize, (December), (accessed March 15, 2005), [availableat http://www.optimizemag.com/issue/014/customer.htm].

Rai, A., N. Patnayakuni, and R. Patnayakuni (2006), “Firm Perfor-mance Impacts of Digitally-Enabled Supply Chain IntegrationCapabilities,” MIS Quarterly, forthcoming.

Reichheld, Frederick F. and W. Earl Sasser Jr. (1990), “ZeroDefections: Quality Comes to Services,” Harvard Business

Review, 68 (September–October), 105–111.——— and T. Teal (1996), The Loyalty Effect: The Hidden Force

Behind Growth, Profits, and Lasting Value. Boston: HarvardBusiness School Press.

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 12/13

14 / Journal of Marketing, January 2006

Reinartz, Werner J. and V. Kumar (2000), “On the Profitability of Long-Life Customers in a Noncontractual Setting: An Empiri-cal Investigation and Implications for Marketing,” Journal of

Marketing, 64 (October), 17–35.——— and ——— (2002), “The Mismanagement of Customer

Loyalty,” Harvard Business Review, 80 (July), 86–94.Reinganum, R.M. (1981), “Misspecification of the Capital Asset

Pricing: Empirical Anomalies Based on Earnings Yields andMarket Values,” Journal of Financial Economics, 12 (March),89–104.

Rust, Roland T., Tim Ambler, Gregory S. Carpenter, V. Kumar,

and Rajendra K. Srivastava (2004), “Measuring Marketing Pro-ductivity: Current Knowledge and Future Directions,” Journalof Marketing, 68 (October), 76–89.

——— and Timothy L. Keiningham (1994), Returns on Quality: Measuring the Financial Impact of Your Company’s Quest for Quality. Chicago: Probus.

———, Katherine N. Lemon, and Das Narayandas (2005), Cus-tomer Equity Management . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

———, Christine Moorman, and Peter R. Dickson (2002), “Get-ting Return on Quality: Revenue Expansion, Cost Reduction,or Both?” Journal of Marketing, 66 (October), 7–24.

Sambamurthy, V., Anandhi Bharadwaj, and Varun Grover (2003),“Shaping Agility Through Digital Options: Reconceptualizingthe Role of Information Technology in Contemporary Firms,”

MIS Quarterly , 27 (2), 237–63.Shiller, Robert J. (2000), Irrational Exuberance. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.Srinivasan, Raji and Christine Moorman (2005), “Strategic Firm

Commitments and Rewards for Customer Relationship Man-agement in Online Retailing,” Journal of Marketing, 69 (Octo-ber), 193–200.

Srivastava, Rajendra K., Tasadduq A. Shervani, and Liam Fahey

(1998), “Market-Based Assets and Shareholder Value: AFramework for Analysis,” Journal of Marketing, 62 (January),2–18.

Venkatesan, R. and V. Kumar (2004), “A Customer Lifetime ValueFramework for Customer Selection and Resource AllocationStrategy,” Journal of Marketing, 68 (October), 106–125.

Wayland, Robert E. and Paul E. Cole (1997), Customer Connec-tions: New Strategies for Growth: Boston: Harvard BusinessSchool Press.

8/3/2019 High Return, Low Risk (1)

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/high-return-low-risk-1 13/13