Help Passenger Rail by Privatizing Amtrak · Amtrak and the Aftermath of the September 11 Terrorist...

Transcript of Help Passenger Rail by Privatizing Amtrak · Amtrak and the Aftermath of the September 11 Terrorist...

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Joseph Vranich served on the Amtrak Reform Council from February 1998 to July 2000. He has also served as pres-ident and CEO of the High Speed Rail Association and executive director of the National Association of RailroadPassengers. Edward L. Hudgins is director of regulatory studies at the Cato Institute.

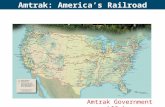

The airport shutdowns and fear of flying thatfollowed the September 11 terrorist attacks gaveAmtrak a boost in ridership. But the government-owned and government-operated passenger rail-road, established by Congress three decades ago,will not likely be able to take advantage of a pub-lic demand for alternatives to air travel. Since itscreation Amtrak has received nearly $25 billion intaxpayer funding, and there is no prospect that itwill ever break even. Unfortunately, Congress isnow proposing to throw billions of dollars in newsubsidies at Amtrak.

In the Amtrak Reform and Accountability Actof 1997 Congress mandated that if Amtrak is notfinancially self-sufficient by December 2002 itmust be restructured and liquidated. Secretary ofTransportation Norman Mineta recently saidthat Amtrak would not meet that deadline.

Amtrak has failed to secure an increasing por-tion of America’s growing transportation market.It carries only about three-tenths of 1 percent of

all intercity passengers. Its on-time performanceon most routes is terrible, and it covers up thisfact by measuring punctuality at a limited num-ber of stops and building in lots of extra timebefore those stops.

Many of Amtrak’s trains run much moreslowly today than did trains on the same routesearlier this century. Moreover, Amtrak uses cre-ative accounting to disguise its financial prob-lems. For example, Amtrak receives many subsi-dies from government agencies and has recentlyabandoned standard accounting practices tohide operating expenses as capital costs.

Congress established an Amtrak ReformCouncil to monitor Amtrak’s financial perfor-mance and decide whether the railroad can meetits deadline for becoming operationally self-suf-ficient. Amtrak clearly will not meet that goal. Itis time for the council to make this finding offi-cial and begin the mandated process of restruc-turing and liquidation.

Help Passenger Rail byPrivatizing Amtrak

by Joseph Vranich and Edward L. Hudgins

Executive Summary

No. 419 November 1, 2001

Amtrak and the Aftermathof the September 11

Terrorist AttacksIn the immediate aftermath of the terror-

ist attacks of September 11, 2001, and thesubsequent shutdown of commercial airtravel, Amtrak reported that it carried twicethe usual number of passengers on its trainsbetween Washington and New York and sawincreased ridership throughout the country.1

The temporary closure of Reagan NationalAirport also put Amtrak in the unique posi-tion of being the fastest means of transporta-tion from downtown Washington to NewYork.2 Amtrak also boosted revenues fromincreased shipments by the U.S. PostalService and United Parcel Service.

Amtrak crowed about “coming to the res-cue of 100,000 passengers nationwide” andbeing “a viable form of transportation.”3 Yet,despite those public pronouncements, it waslater learned that Amtrak’s Beech Grove,Indiana, maintenance facility asked employ-ees to “double their production” and said“the biggest push” was on repairing mail carsand baggage cars, not passenger cars.4

The proper objective for Amtrak duringsuch a time of need would have been to repairas many sidetracked passenger cars as possi-ble. So much for Amtrak going the extra mileto move people in a pinch and taking advan-tage of an opportunity to attract passengerspermanently to rail travel.

As more aircraft returned to the skies,reports indicated an easing in the number ofsold-out trains. Inquiries to Amtrak about itstraffic failed to clarify if the passenger surgewas lasting. By September 20, Amtrak’s WestPalm Beach traffic was “thinning out andreturning to normal.”5 One week later the LosAngeles Times reported:

The surge of passengers who flockedto Amtrak trains in the days after theterrorist attacks has begun to sub-side, dimming hopes that the interci-ty rail service could attract lots of

new passengers amid the airline cri-sis. . . . Amtrak officials provided fewspecifics concerning ridership totalsfollowing the terrorist attacks. Theysaid, however, that ridership nation-wide was up an estimated 17% in thefirst week . . . . On Wednesday [Sept.26], Amtrak said the increase sincethe attacks had fallen to somewherebetween 10% and 13%. They declinedto provide week-by-week or dailybreakdowns of ridership. An infor-mal survey conducted Wednesday byCarlson Wagonlit Travel, one of thenation’s biggest travel agency chains,also suggested only a slight switch toriding the rails.6

Amtrak Trips Now More Competitive? The market for passenger train service

may have expanded because the added timerequired for airport security checks—someairports recommend arriving four hoursbefore a flight—makes trains more competi-tive. That certainly is true on the Boston-NewYork-Washington route, and may be true fora few more niche markets.

Consider the Chicago-St. Louis rail line.Amtrak allots 3 hours and 17 minutes totravel the Chicago-Springfield segment, aschedule that is not normally competitivewith air travel. But when allowing for anextra hour or two at the airport, the scheduleon this segment becomes competitive withaviation. The key is to keep expectations real-istic—the 5 hours and 40 minute schedule forthe entire Chicago-St. Louis route means thetrain still cannot compete with air traveltimes. In light of increased airport delays, it isreasonable to assume that trains would becompetitive with air travel on routes that are25 to 60 miles (depending on the speed of thetrain) longer than routes that were previous-ly considered competitive, provided the terri-tory involved aligns with an air market. Andthe longer the air delays, the longer the addi-tional distance over which rail would be com-petitive.

This small Amtrak competitive advantage

2

The nationshould not stay

wedded to theAmtrak para-

digm, which hasbeen a colossal

failure for 30years.

ignores the possibility of extra time that may beneeded for security checks in train stations.Amtrak now requires passengers to show validphoto identification when buying tickets andchecking baggage. Amtrak is working with theFBI to determine if it should institute measuressuch as screening baggage and checking pas-sengers through metal detectors.7 Meanwhile,U.S. Department of Transportation secretaryNorman Y. Mineta has questioned the need torequire rail customers to pass through metaldetectors before boarding Amtrak trains.8

Additional experience is needed to deter-mine the degree to which these changing fac-tors will help or hinder Amtrak.

Overreaching in WashingtonIn a display of political opportunism,

Amtrak is requesting $3.2 billion in “disasteraid” even though no disaster exists atAmtrak.9 In fact, Amtrak has profited fromtravelers’ reluctance to fly. Amtrak’s request-ed bailout is more excessive than the one theairlines received. Consider that airlines aver-aged 1.8 million passengers a day andreceived $5 billion in grants and $10 billionin loan guarantees. Amtrak carries fewer pas-sengers—typically 60,000 a day, and up to80,000 at the peak of the airline diversion—but wants a whopping $3.2 billion in grants.The disparity should surprise no one becauseAmtrak has no upper limit to the amount ofsubsidies it seeks. Amtrak’s current politicalposture is a low point in Amtrak’s history. Asone congressional aide told Reuters,“Amtrak’s agenda, as usual, is capitalizing on[the attacks] in a bogus way.”1 0

It must be acknowledged that Amtrakwould use a portion of the funds to correctfire and safety problems in the tunnels lead-ing to New York’s Penn Station. But that verylack of repairs is an indictment of Amtrakpolicies. Amtrak has long known about theneeded work; as the first report pointing tothe problem was issued in 1978,1 1 and otherreports have been issued since.1 2But Amtrakfailed to launch a tunnel improvement proj-ect for 23 years while it squandered billionsof dollars on lightly used trains elsewhere

and on glamorous projects that yielded apoor rate of return. If given the funding,Amtrak will undertake needed tunnel work.But Amtrak also will waste a good portion ofthe $3.2 billion on pork-barrel trains thatserve few travelers.

Amtrak also is poised to benefit fromthree other pieces of legislation.

Under consideration is the $12 billion HighSpeed Rail Investment Act of 2001, whichwould not really bring about high-speed trains(more will be said about this later).

Also being discussed is an ill-advised stimu-lus package that includes $37 billion, a goodportion of which would expand Amtrak.1 3

Commented one editorial, “A vastly expandedpassenger rail system would do little for thenation’s security and, if the system is a white ele-phant, the short-term economic stimuluswould become a long-term economic burden.”1 4

One measure, named the RailInfrastructure Development and ExpansionAct for the 21st Century, or RIDE-21, pro-poses to spend $71 billion on a broad rangeof railroad-related projects.1 5 Although thebill appears to minimize Amtrak’s participa-tion, the fact remains that Amtrak’s de factomonopoly in intercity passenger service posi-tions the railroad to feed at this additionalgovernment trough.

The rush to throw money at Amtrak rep-resents government at its worst. The nationshould not stay wedded to the Amtrak para-digm, which has been a colossal failure for 30years, because terrorists’ acts have boostedtrain travel. Amtrak is the same mismanagedorganization after September 11 that it wasbefore that date. Additional subsidies will donothing to reverse Amtrak’s high costs andabysmal productivity and are likely to furtherinstitutionalize poor Amtrak practices.

Choosing to expand rail service throughAmtrak instead of induce the creation ofnew, more efficient entities reflects morethan the usual lack of governmental imagi-nation; it reflects congressional panic and adedication to a dysfunctional system, both ofwhich are counterproductive to meetingfuture transport needs.

3

The giveawayfares appear to bea move to buildridership at anycost. Unfortu-nately, that costcould be billionsof dollars in newtaxpayer subsidies.

Amtrak’s New Fares a Clue to ItsTroubles

Amtrak’s central marketing ploy has longbeen to offer low fares, one thing that hasmade federal subsidies per passenger muchhigher for Amtrak than for any other modeof transportation. But why must Amtraklaunch a new round of super-cheap faresafter the post-September 11 influx of airlinetravelers? A September 29 check of Amtrak’sWeb site reveals travelers can “save up to 70%off regular coach fare.” These “exclusiveonline fares,” even with Amtrak limiting theseating, are astonishing. For little more thanthe price of a roundtrip on Washington’ssubway, it’s possible to ride Amtrak fromIndianapolis to Chicago. Generally effectiveOctober 9, the one-way fares are

$3.40—Indianapolis to Chicago(This fare was $6.23 in April 1953.)16

$3.90—St. Louis to Bloomington, Ill.$6.60—Chicago to Jeffersonville(Louisville)$11.70—Cleveland to Philadelphia$12.20—Chicago to Harrisburg$13.60—Seattle to Vancouver, B.C.$15.90—Sacramento to Bakersfield$16.00—Philadelphia to Chicago$17.20—Chicago to Detroit (TheAmtrak fare in 1971 was $16.25.)1 7

$17.40—Chicago to St. Louis (TheAmtrak fare in 1971 was $13.50.)1 8

Other oddities: Take, for example, a trainthat Amtrak repeatedly calls a “success”—theTexas Eagle, which runs between St. Louis andSan Antonio. Amtrak offers a discount fare of$81.60 for exceptionally long periods, forexample, from September 25 throughDecember 17, 2001, and from January 7through June 14, 2002. Cut-rate deals are alsoavailable in the busy Washington-BostonNortheast Corridor, where Amtrak says thetraffic increase has been most pronounced.1 9

Amtrak is still offering a “buy two, get onefree” promotion for rides on the Acela Expressbetween Boston and New York.20

As of September 29, attempts to book

space at the super-cheap fares succeeded on anumber of days associated with heavyThanksgiving travel.2 1 Policymakers whocontrol the public’s purse strings must ques-tion Amtrak’s costly practice of institutinggiveaway fares during busy travel seasons andwhile supposedly inundated with airline trav-elers. The giveaway fares appear to be a moveto build ridership at any cost. Unfortunately,that cost could be billions of dollars in newtaxpayer subsidies.

Amtrak and Its Future RidersWill Amtrak’s new riders stick with the

railroad? History says no. The nation suf-fered a major shutdown of commercial avia-tion in 1966 when labor strife caused simul-taneous strikes at virtually every U.S. airlinefor several days. The effect on rail traffic, thenoperated by private railroads, was electrify-ing. Passenger trains were full for the firsttime in years and long lines were seen at tick-et windows. Prior to this strike, the passengertrain had been in a long downward spiral,and it was typical for traffic to decline by 7 or8 million passengers from year to year. In1966, however, the airline strike caused a lev-eling off in the decline to only 996,000 pas-sengers. But when the airplanes returned tothe skies so did the passengers. The 1997traffic fell by 7.2 million passengers com-pared to the prior year, rather typical for thatera.2 2 Amtrak will not experience such asharp loss, because the billions of dollars itreceives in taxpayer subsidies enable it toretain riders through pricing schemes. Theprivate railroads that preceded Amtrak hadno such access to public subsidies.

A labor strike is different from a wide-spread fear of flying, but even terrible aircrashes have failed to spark a long-term shiftto passenger rail. On May 25, 1979, anAmerican Airlines DC-10 crashed after takeofffrom Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport,resulting in the highest death toll in Americanaviation history. Amtrak experienced a trafficgain, which quickly dissipated.

Consider the peak of the 1995 summertravel season. New York’s three airports were

4

A string ofreports in recent

years paints a picture of a rail-

road that isunable to control

expenditures.

placed under tightened security because ofthreats of terrorist attack. Airline passengersendured many delays as security checksintensified. For several weeks, hundreds offlights were delayed. Yet, Amtrak’s patronagewent down a million from the year before.

Safety fears mounted sharply in 1996,when within two months a ValuJet DC-9crashed in the Florida Everglades and a TWABoeing 747 crashed into the Atlantic Oceanoff the Long Island coast. In 1997, airline acci-dents occurred in the Dominican Republic,Peru, Nigeria, Zaire, Brazil, Ethiopia (a hijack-ing), and Indonesia. India suffered the world’sworst midair collision. Still, Amtrak trafficdropped lower in each of those two years thanin any year between 1985 and 1995.

Other examples demonstrate that Amtraktraffic surges evaporate when caused byexternal events. In the 1970s the UnitedStates suffered two gasoline shortages. Thefirst resulted from the outbreak of the Arab-Israeli War in October 1973, when OPECimposed an oil embargo against Westerncountries; the second resulted from Iran cut-ting its oil production for six months prior toApril 1979. Each time, airline fares and gaso-line prices skyrocketed, and lines of cars wait-ed at filling stations. Both times Amtrak rid-ership surged. A typical headline read“Gasoline Lines and Cost of Flying LeadingMany to Try Rail Travel.”2 3 But in each case,when fuel became more readily availableAmtrak ridership declined or stagnated.Nine years went by before Amtrak carriedmore passengers than it did in 1979.

Amtrak’s Future with Airline PassengersAdmittedly, fear of flying is different

today than it was in the past. No one knowswhat travel trends will evolve, but it is knownthat Amtrak does not enthrall all airline pas-sengers. Anecdotal evidence is building thatairline travelers resist traveling by Amtrak.Consider:

• Many business travelers say it’s hard tobeat jetliners for long trips despite thenew safety concerns. . . . “‘Time is

money,’ said Joe McClure, a LosAngeles–area travel agent and owner ofMontrose Travel. ‘Corporate travelersdon’t have the time to waste gettingfrom point A to point B.’”24 That viewwas echoed by Kelly Kuhn of NavigantInternational in Chicago, who said:“We certainly have not seen an increasein selling tickets. Amtrak is not really aviable option.”25

• A leisure airline traveler, Kathy Brownof Santa Barbara, says for a long vaca-tion Amtrak is out of the questionbecause “it would take me two or threedays to go where I want to go byAmtrak.”26

• Amtrak’s lack of security measuresprompted Danielle Fidler of Alexan-dria, Virginia, to write: “It is inexcusablefor Amtrak to neglect even the mostbasic safety precautions. Although I amscheduled to take the train to New Yorksoon, I think I would rather fly.”2 7

Lavita Jones of Los Angeles boardedAmtrak’s Metroliner, saying: “It’s justlike it’s another day. Anyone could justwalk on with anything. I feel safer on anairplane.”2 8 Alfred Benner, a Michiganbusinessman, said: “The security is evenworse on trains than planes. I’ll be dri-ving to Boston to see my family over theholidays, thank you very much.”2 9

• Conditions aboard trains leave cus-tomers unimpressed, or worse. Passen-ger Steven Green, planning to return toNew Jersey from Florida on Amtrak,wondered, “How bad could it be? Bythe time he got off the train almost 30hours later (and more than four hourslate) he knew. . . . He was awakenedevery time the door in the car openedand slammed shut. . . . Then there werethe bathrooms, which he says weren’tcleaned en route and became filthy. ‘Irefused to use them,’ he says. ‘The bestthing about the train was gettingoff.’”3 0

Thus, even in light of the changes in the

5

To cover short-term operatinglosses Amtrakmortgaged PennStation in NewYork as collateralfor a $300 millionloan.

transportation market that have resultedfrom the September 11 attacks, the future ofAmtrak must be considered in light of its his-tory and current operational problems.

Amtrak’s CurrentFinancial Crisis

Aviation crisis or no, Amtrak is doomed toperpetual failure. In recent years Amtrak hasreceived a record level of public subsidies toimprove service, boost efficiency, and set thestage to be free of federal operating hand-outs. But the railroad continues to provideinadequate service to many of its passengers,has become less efficient, and shows littlesign that it can survive without substantialfederal operating funds.

Amtrak’s legacy of failure dates back toMay 1, 1971, when it was established byCongress as a federally owned and operatedpassenger railroad. At that time policymak-ers believed that passenger rail service wasimportant enough to necessitate the govern-ment running such a system. Nixon adminis-tration correspondence on Amtrak stated, “Itis expected that the corporation would expe-rience financial losses for about three yearsand then become a self-sustaining enter-prise.”3 1In fact, since its creation the systemhas always run at a loss, requiring substantialsubsidies to keep it afloat.

Infusions of $3.91 billion in federal subsidiesfrom 1998 through 2000 provided Amtrak withmore taxpayer funding than in any other 3-yearperiod in its 30-year history. But it seems that themore Amtrak receives, the greater its financial dif-ficulties. According to recent congressional testi-mony by the inspector general of the U.S.Department of Transportation, “Four years intoits mandate for operating self-sufficiency, Amtrakshould be showing signs of significant improve-ment, not standing in place or, worse, movingbackwards.”3 2

Amtrak’s credibility has suffered as execu-tives have repeatedly issued glowing reportsabout recent revenue increases.3 3But a stringof reports in recent years paints a picture of a

railroad that is unable to control expendi-tures or generate adequate revenues. Reportsfrom the 1994–99 period are replete withsuch warnings, including one that saidAmtrak was borrowing money to pay foroperating expenses, “including those for pay-roll, fuel, ticket stock, and food.”3 4 InSeptember 2000 the General AccountingOffice warned, “While Amtrak has ‘spentmoney to make money,’ it has realized littlebenefit from the expenditures it has made.”3 5

In March 2001 a GAO representative toldCongress, “Amtrak has made minimalprogress in reducing its budget gap in orderto reach operational self-sufficiency.”3 6 Buton July 25 the GAO admitted: “It is veryunlikely that Amtrak can operate a nationalintercity passenger rail system as currentlystructured without substantial federal oper-ating support. The outlook for it achievingoperational self-sufficiency is dim.”3 7

The Department of Transportation,Office of the Inspector General, had warnedin March 2001: “Amtrak’s overall financialresults have not improved significantly since1999. . . . Our assessment of Amtrak’s 2000business plan identified a number of ele-ments that are unlikely to perform as Amtrakhad expected. If no corrective action weretaken to compensate for them, Amtrak’s cashloss would be about $1.4 billion more than itprojected over the four-year period 2001through 2004.”38

A principal problem is that costs are risingfaster than revenues, according to congres-sional testimony given in July by the DOTInspector General (DOT IG):

Amtrak’s fiscal year 2000 operatingloss of $944 million, includingdepreciation, was $28 million morethan its 1999 loss and the largest inAmtrak’s history. . . . The pictureremains bleak into 2001, where inthe first eight months revenues grewby $15 million over the same perioda year earlier but cash expenses grewby $53 million. Moreover, as ofSeptember 2000, Amtrak’s long-

6

Congress passedthe AmtrakReform andAccountabilityAct of 1997 in anattempt once andfor all to dealwith Amtrak’sthree-decades-oldproblems.

term debt and capital lease obliga-tions totaled $2.8 billion, an increaseof $1 billion over 1999.39

To cover short-term operating losses untila new federal appropriation becomes availablein October, Amtrak mortgaged Penn Stationin New York as collateral for a $300 millionloan.4 0Said Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz..):

I am informed this transaction wasout of desperation because Amtrakwould become insolvent within thenext month without an immediateinfusion of cash. . . . I also under-stand the actual cost to repay the$300 million dollar loan will be near-ly $600 million over the 16-year lifeof the loan. How is funding a fewmonths of operating costs over a 16-year period a sound business judg-ment? It simply isn’t.4 1

Amtrak’s financial condition remains pre-carious despite the loan. In July 2001 the rail-road offered 2,900 employees a voluntary sep-aration through early retirement and otherincentives.42 Whether that effort will be suc-cessful remains to be seen. As GAO notes:

Amtrak attempted to reduce itsmanagement staff in 1994 and 1995by offering employees early retire-ment and buyouts to leave the com-pany. As a result Amtrak’s manage-ment staff declined by a total ofabout 15 percent between 1994 and1995. But, by 1999, the number ofmanagement employees was almostthe same as it was in 1994. Union-represented employment declined 7percent from 1994 through 1996.But union-represented employmenthas also grown since then, and, in1999, Amtrak had more union-rep-resented workers than in 1994.4 3

A report issued by the Working Group onIntercity Passenger Rail in June 1997 found

that Amtrak faces a major liquidity crisis andprobable bankruptcy, long-distance trainsmake more sense as “rolling National Parks,”passenger rail service should be opened tocompetition, Amtrak’s monopoly shouldend, and reforms launched by Amtrak havenot paid off.44

The Amtrak Reform Council echoedmany of these views by stating in March2001: “Amtrak’s performance in FY 2000 wasapproximately $100 million short of its goal.Revenues were lower than expected, costswere higher than planned, and productivityimprovements did not produce measurablefinancial gain.”45

All of these findings should come as no sur-prise in light of some of GAO’s conclusions aboutAmtrak’s chronic problems. For example:

• “Amtrak’s expenses were at least twotimes greater than its revenues for 28of its 40 routes in fiscal year 1997. Inaddition, 14 routes lost more than$100 per passenger carried.”46

• “During fiscal year 1997, five Amtrakroutes each carried more than 1 millionpassengers, accounting for nearly 60 per-cent of the railroad’s ridership. In contrast,17 Amtrak routes carried only about 10percent of Amtrak’s total ridership.”47

• “During fiscal year 1997, fewer than100 passengers, on average, boardedAmtrak intercity trains and connectingbuses per day in 13 states . . . the rela-tively large number of states with rela-tively low ridership, along with otherfinancial performance data, is indica-tive of Amtrak’s financial performanceproblems.”4 8

Congress has virtually ignored those find-ings and, in defiance of all logic, is consider-ing additional funding boosts for Amtrak.

Setting Low Reform Goals

Congress passed the Amtrak Reform andAccountability Act of 1997 in an attempt

7

Amtrak has yet touse its freedom todiscontinue a sin-gle money-losingservice.

once and for all to deal with Amtrak’s three-decades-old problems. But Anthony Haswell,who is sometimes referred to as the “father”of Amtrak and who helped write the 1970law that created Amtrak, saw the legislationas setting modest goals. He wrote, “In view ofCongress’s impatience with Amtrak’s chron-ic deficits and underwhelming market per-formance, the reforms it demanded were rel-atively few and unobjectionable.”49 Indeed,the ARAA is a pale shadow next to the imag-inative methods foreign nations have used totruly reform their railroads. Consider the sig-nificant features of the ARAA:

• Amtrak must be financially self-sufficientby FY 2003, that is, by December 2, 2002.After that it will no longer receive federaloperating subsidies, although it willremain eligible for capital subsidies.Amtrak President George Warringtonhas complained that this requirement isan “artificial political test.”50

• A new seven-person Reform Board ofDirectors was to be composed of indi-viduals with “technical qualifications,professional standing, and demon-strated expertise in the fields of trans-portation or corporate or financialmanagement.” But President Clintonappointed mostly politicians with norelevant expertise and reappointed twomembers from the predecessor boardand one who had served earlier in thedecade.

• Amtrak was given freedom to changeits route system in response to the mar-ketplace, unlike under the congression-ally mandated “basic system” of thepast. Though Amtrak presidentWarrington still complains about poli-cies that require the railroad to provideservices but fail to provide adequatefunding,5 1 Amtrak has yet to use itsfreedom to discontinue a single money-losing service that was in operation theday the law passed.

These modest reforms so far have failed to

change Amtrak’s status quo.

Amtrak Squanders an“Income Tax Refund”

In section 977 of the Taxpayer Relief Act of1997, Congress required that the InternalRevenue Service give Amtrak a $2.184 billion“income tax refund”—even though Amtrakhas never paid federal income taxes.5 2Amtrakreceived the funds in two equal installments infiscal years 1998 and 1999.

Congress meant for the funds to be spentfor “the acquisition of equipment, rollingstock, and other capital improvements” andpayment of interest and principal on obliga-tions incurred for such purposes.5 3 At thetime, Amtrak argued for the funding byasserting it would “make it less expensive tooperate the national passenger rail system.”5 4

The ARC had a statutory responsibility tomake certain that Amtrak “tax return” expen-ditures were used wisely. The first Amtrakreport describing TRA-financed projects wasreplete with phraseology stating that Amtrakwas making a “wise investment” of itsresources and that funds were being commit-ted for “high rate-of-return” projects selectedafter “rigorous evaluation.”55

Amtrak was within legal bounds in usingthe money in part to repay a portion of a $2.8billion debt to the private capital marketsand in part to invest in high-yield,interest-bearing accounts. But such spendingstill did not result in a large return on invest-ment, which was what the “income taxrefund” was supposed to produce.

The first TRA report suggested Amtrakwas still following discredited spending pat-terns by ignoring high market-growth oppor-tunities. Amtrak’s first expenditure of $360million was spread across a broad geograph-ic area. Half of that expenditure went to theleast profitable routes, where the money pro-duced no return on the investment.56 Amtrakthrew good money after bad.

When questioned, 5 7Amtrak officials wereunable or unwilling to provide sufficient

8

Amtrak’s worsen-ing financial loss-

es indicate thatthe railroad failedto wisely invest its

“income taxrefund” on “high

rate-of-return”projects selected

after “rigorousevaluation.”

information to indicate how TRA expendi-tures would move Amtrak toward balancingits budget or how project rates of returnwould help reduce losses on individual poor-performing routes. Amtrak asserted it was“not producing the data in that context atthis time.”58 Yet when I worked in Amtrakheadquarters in the 1970s and served on thePassenger Service Committee, we recom-mended capital expenditures to the board onthe basis of just such estimated rates-of-return. The fact that Amtrak’s moreadvanced accounting systems cannot gener-ate such information today reflects eitherwillful obstruction or gross mismanagement.The ARC’s difficulty in securing informationfrom Amtrak suggests that Amtrak is notserious about reforming its wasteful ways.

The ARC eventually reported significantproblems in how TRA funds were used. In2000, the council stated, “Amtrak has not useda significant portion of the funds for the kindsof high-priority, high-return investments thatwill help its bottom line.”5 9 Early in 2001 theARC reported, “Through December 31, 2000,about $590 million—or 26 percent of total TRAcommitments—have in effect been used forexpenditures that most companies and general-ly accepted accounting principles . . . wouldtreat as ordinary operating expenses or requiredcapital expenditures.”6 0

In February 2000, the GAO stated thatAmtrak’s quarterly reports to the ARC on theuse of TRA funds “do not fully disclose theextent to which Amtrak has used these fundsfor equipment maintenance. As a result thesereports are less useful than they could be inhelping the council comply with its responsi-bility to monitor Amtrak’s use of TaxpayerRelief Act funds.”6 1Again, history was replay-ing itself as the GAO’s comments echoed theassessment by the Working Group onIntercity Passenger Rail, which found thatAmtrak subsidies “are not directed to activi-ties of maximum benefit.”6 2

Amtrak’s worsening financial losses indi-cate that the railroad failed to wisely invest its“income tax refund” on “high rate-of-return”projects selected after “rigorous evaluation.”

Amtrak’s Credibility Crises

Amtrak officials have continually assuredCongress, the public, and the press thatAmtrak is getting its finances in order andimproving the quality of its service. Whenquestioned about problems Amtrak officialsoffer easy answers and rosy predictions. But aclose look at the railroad calls its credibilityinto serious question. That is why Amtrak isbeginning to pay the price for incessanthyperbole about “progress” as its bank bal-ances and credibility are diminishing. Manylong-term Amtrak observers agree withSenator McCain’s testimony before a Senatehearing in June 2001:

I trust one of the Subcommittee’sgoals is to receive an accurate assess-ment of Amtrak’s current financialsituation and not to simply sitthrough another day of testimonyfrom Amtrak as it spins the “facts,”provides only half-truths, and makesmore promises that will go unmet. . . .Isn’t Amtrak under an obligation toprovide the Congress with accurateand timely information? Do we needto start swearing in Amtrak witnessesbefore our hearings begin in order tohelp ensure we receive honest testi-mony?63

Disparaging comments regarding Amtrak arefrequent because of the railroad’s misrepre-sentations in 10 areas involving policymak-ing—and performance.

Credibility Crisis # 1: Acela Express DelaysThe media have widely reported that the

Acela Express is one year behind schedule.That time delay is technically accurate only ifdelivery dates for Acela Express trains arecompared with the manufacturer’s contractdeadlines. In terms of high-speed rail promis-es that Amtrak made to Congress whenrequesting funds, Amtrak is two and a halfyears behind schedule. The inaugural of

9

Amtrak is begin-ning to pay theprice for inces-sant hyperboleabout “progress”as its bank bal-ances and credi-bility are dimin-ishing.

high-speed service was supposed to occur in1998; Amtrak’s Acela Express started inDecember 2000.

The costs of Amtrak-developed high-speedrail in both delays and money began with thedecision concerning equipment design. OnFebruary 1, 1993, Amtrak began operating theX2000, a high-speed tilting train used inEurope. Passenger reaction was enthusiastic—one saying “I thought I had walked onto acloud”—as travelers took in the X2000’s luxu-rious touches including “large plush seats,wheelchair lifts, carpeting, coffee stations ineach car, telephones, fax machines, and elec-tronic displays.”64 The train’s performancewas superior to that of all existing Amtraktrains, and the speed capability, at 155 mph,meant the train could shave 15 minutes offthe schedule of the fastest New York-Washington Metroliner.6 5 The performancewas equivalent to that of the Acela Express.Although the X2000 was tested successfully,the train required modifications to meetAmerican rail safety standards. The train’sSwiss-Swedish manufacturers were preparedfor that engineering task and promised tobuild the X2000 in this country.

Had Amtrak opted to purchase suchproven technology, it could have had high-speed rail in operation in the NortheastCorridor as early as 1996–97. But Amtrakdecided instead to design a new train, a com-petence it is not known for, and the result isthe delay-prone Acela Express and severalyears worth of diminished revenue-generat-ing capacity.

Consider the chronology:May 19, 1993. When initiating the high-

speed train procurement, Amtrak said that inorder to qualify a firm must be able to “deliv-er two complete train sets by April 1996 andthe remainder of the train sets within twoyears thereafter.”6 6

November 3, 1993. “Amtrak plans to awarda contract by the middle of 1994 with thefirst trains being delivered two years later.”6 7

March 17, 1994. The projected delivery dateslipped as Amtrak officials informedCongress: “Two advance versions of the train

sets are expected in early 1997 for testing.The remaining 24 train sets will then go intoproduction, with the final train set arrivingin 1999.”6 8

October 6, 1994. Amtrak reiterated the dead-lines, adding: “The 26 high-speed trains willattain top speeds of 150 miles per hour. . . . Theprocurement award is expected in early 1995. . .. It is expected by the year 2000 that more thanthree million additional passengers will beattracted to the service.” Amtrak also reiteratedits promise that New York-Boston travel timewould be reduced to “under three hours.”69

March 17, 1996. The Associated Pressreported that Amtrak had selected a consor-tium to build the trains that would “go intoservice by 1999,” a two-year slip from the1997 start date.7 0

March 11, 1998. Amtrak representativestestified before a House committee that “fivetrain sets will be delivered in late 1999, withthe remaining 13 by July 2000.”71

December 11, 2000. The first Acela trainsbegan running on this date.

As delays increased, Amtrak changed thename of the trains from “Metroliners” in theearly 1990s, to the “American Flyer” when theequipment order was placed in the mid-1990s, and to the “Acela Express” to create a“brand image” beginning in March 1999.7 2

After promising a New York-Boston tripin “under three hours,” Amtrak has nowdelivered a three-and-a-half-hour run. In1950 the New Haven Railroad’s MerchantsLimited linked New York and Boston in fourhours without the benefits of full electrifica-tion, tilt-train technology, and advanced sig-naling systems. For the Acela Express to runonly about 30 minutes faster after Amtrakhas spent billions of dollars on the project isan example of Amtrak’s inability to bringhigh-speed rail service that is truly competi-tive with air travel to America.

The slow pace reflects the fact that AcelaExpress operates at 150 miles per hourbetween New York and Boston on only 18 ofthe route’s 231 miles.7 3 By contrast, Japan’sfirst Bullet Trains, which are now in muse-ums, offered faster trip times in the 1960s

10

Had Amtrakopted to purchasesuch proven tech-

nology, it couldhave had high-

speed rail in oper-ation in the

NortheastCorridor as early

as 1996–97.

than the Acela Express offers in 2001.Design Flaws and Delays. When the Acela

Express was delivered for testing, designflaws delayed production and deployment.Early in 1999, the news media revealed thatthe trains were built four inches too wide toallow full use of the tilt mechanisms, and thetrains would be unable to take the numerouscurves between Boston and New York as fastas planned.7 4 Amtrak and rail equipmentsuppliers Bombardier of Quebec andBritain’s GEC Alsthom, have bickered overthe cause of the design flaw, most likelybecause the contract includes late-deliverypenalties.7 5 Next, during test runs, the trainssuffered from excessive wheel wear.76 By June2000 Amtrak halted Acela Express test runsbecause of cracked or missing bolts in thewheel assemblies.7 7 Another halt came amonth later when broken bolts were foundon components that help steady the ride ofthe passenger cars.7 8

With testing completed, the trains wentinto commercial service on December 11,2000. The Acela Express was sidelined the nextday because of damage to its pantograph, thedevice that connects the train to overhead elec-trical wires, and a second Acela Express held inreserve was also found to be inoperable, sopassengers were put on an older Metroliner,which ran late.7 9Acela Express trains have bro-ken down in Stamford, Connecticut,8 0 andnear Philadel-phia; in the latter case, passen-gers were delayed several hours and treatedpoorly. One passenger wrote: “Once inPhiladelphia, we were told to go into the sta-tion where someone would be waiting to helpus. There was no one there even remotelyaware of our plight. In the end, we had toargue with the agents to honor our tickets andget us on the next train to Washington.”8 1

Passengers have reported similar experiencesin other Amtrak stations.

It is uncertain what effect the Acela Expresswill have on Amtrak revenue. In one instance,DOT IG Kenneth Mead has questioned thereasonableness of Amtrak’s 2000–2004 rev-enue estimate of $4.1 billion for the NortheastCorridor, instead projecting that revenues will

be $304 million lower.82 He said, “We are con-cerned that Amtrak’s projections for AcelaExpress ridership assume a higher-than-likelydiversion of passengers from air and automo-bile, and an underestimation of ridership onthe slightly slower, but significantly lessexpensive Acela Regional service.”8 3 But in aJuly 2001 statement, he said, “Our initial find-ings in our current annual assessment indi-cate that given the level of airline delays,Amtrak’s projections for Acela revenue whenfully ramped up may now, in fact, be some-what conservative.”8 4

The question arises, What is high speed andat what price? Amtrak hopes that the fasterAcela Express trains will allow it to better com-pete with airlines in the Northeast Corridor,but the degree of success is an open question.

Between Washington and New York pas-sengers currently have three price options(weekday rates, one way): The Acela Expressat $144, the Metroliner at $125 (to be phasedout and replaced by the Acela Express), andthe Acela Regional at $69. It is open to ques-tion how many travelers will opt for the AcelaExpress over the Acela Regional, since the lat-ter is generally only 42 minutes slower thanthe Acela Express but costs $75 less.

A similar situation exists between NewYork and Boston. The current Acela Expresstime of 3 hours and 30 minute, whichAmtrak says will be speedier in the future, is25 to 35 minutes faster than that of the AcelaRegional trains. Whether that time differencewill justify a ticket price of $120 (versus $58for the slower train) is open to question.

Prior to the airline hijackings and thealtered transportation landscape in theNortheast Corridor, Amtrak asserted thatthe Acela Express would reduce aviation con-gestion. But if aviation conditions return tonormal in the Northeast, the evidence sug-gests Amtrak’s best train will have only aminimal effect. If Amtrak is to attract airlinetravelers, it must be able to run trains that arenot only faster but more reliable than planes.The Acela Express record so far has beenmixed. For example, during the week of July1, only 26 percent of Acela Express trains in

11

Acela Expressoperates at 150miles per hourbetween NewYork and Bostonon only 18 of theroute’s 231 miles.

and out of Boston showed up at or beforescheduled arrivals.8 5Also by August 2001, theAcela Express was “falling short of projec-tions in ridership and revenue. Reimburse-ment requests from dissatisfied customersare three times higher than Amtrak’s goal[and] a nonstop Washington-to-New Yorkservice—Amtrak’s silver bullet in its race withair shuttles—has been suspended due to lowridership.”8 6

When some sense of normalcy returns tothe aviation system, it is reasonable to expectaggressive airline competition against theAcela Express. The airlines weren’t standingstill prior to the September 11 tragedies.Moreover, aviation competitors are not stand-ing still. In the past two years, U.S. AirwaysShuttle added new Washington-New Yorkdepartures using newer Airbus A320 aircraft.8 7

The Delta Shuttle set passenger boardingrecords during the Thanksgiving weekend of2000, including its busiest day ever atWashington’s Reagan National Airport,attributing its success in part to the positivecustomer reception for its new Boeing 737-800 aircraft.88 Also, Amtrak’s Acela will donothing to hamper what will likely be aregrowth of fairly new Northeast Corridor air-line routes, such as Southwest Airlinesbetween Providence and Baltimore-Washington International, because of the dis-tance involved. Growth is occurring elsewhere,such as between Islip Airport on Long Islandand BWI, or the Atlantic Coast Airlines servicebetween Dulles International Airport nearWashington and Newark. Amtrak goesnowhere near Islip and Dulles airports andholds little allure for the growing number oftravelers in nearby communities.

Airport expansion plans in the Northeastare progressing despite the current drop intraffic. Various expansion plans are movingforward at Newark International Airport,Philadelphia International Airport, BWI, andDulles International Airport .8 9

The Acela Express, despite its shakystart, is an attractive train that holds promisefor the Northeast. It will likely make a contri-bution to mobility during these difficult

times. But considering Amtrak’s record ofdelays and the intensity of airline competi-tion, the promise of the Acela Express easingaviation congestion during normal periodsin the Northeast Corridor is false.

Credibility Crisis # 2: National PassengerTraffic

More passengers ride trains today than 30years ago when Amtrak was created, andAmtrak boasts that its fiscal year 2000 rider-ship of 22.5 million passengers set a newrecord. Amtrak vice chairman MichaelDukakis stated in the New York Times that “inJuly [2001] Amtrak recorded its highestmonthly ridership in 22 years.”90 But Amtrakexaggerates ridership gains. According to theARC, “During a decade when the Americaneconomy and most of its transportation sys-tem have expanded in an unprecedentedmanner, Amtrak’s ridership has remainedvirtually unchanged.”9 1

Amtrak’s level of usage is an indictment ofits market-insensitive network for the follow-ing reasons:

• Year 2000 ridership was only a half-mil-lion passengers higher than in 1990and 1991, hardly an impressive featconsidering that the decade saw an all-time record growth in domestic travel.

• The record came in the same yearAmtrak suffered a record financial loss,because train tickets are seriouslyunderpriced considering Amtrak’shigh cost structure.

• Passenger-miles are a more credibleindex for quantifying the volume ofbusiness. On that basis the quantity ofAmtrak’s passenger-miles was lower in2000 than at its peak, from 1988through 1994 (see Table 1).

For perspective, on Memorial Day week-end 2000, domestic aviation served well over12 million passengers. In just one holidayweekend airlines carried more than half thetraffic Amtrak moves in an entire year. Thegap has been growing despite aviation con-

12

Amtrak suffered arecord financial

loss, because traintickets are seri-

ously underpricedconsidering

Amtrak’s highcost structure.

gestion. In Amtrak’s first full year of opera-tion in 1972, it carried an average of 45,500passengers a day. In 2000, more than a quar-ter-century later, Amtrak ridership stood atonly 61,643 daily. Meanwhile, airline trafficreached 665.5 million in 2000,92 and thenumber of airline passenger trips has morethan tripled, from 524,100 daily in 1972 to

1,823,287 daily in 2000.Amtrak’s inability to adapt to market

demands is why its share of the intercity trav-el market is lower than ever—only aboutthree-tenths of 1 percent of intercity passen-ger trips in the United States. Even privateaircraft, at six-tenths of 1 percent, serve dou-ble the number of passengers.9 3

13

Amtrak’s share of the intercitytravel market is only aboutthree-tenths of 1 percent of intercity passen-ger trips in theUnited States.

Table 1Amtrak versus Aviation Ridership

U.S.Census Airline AmtrakPopulation Revenue Amtrak Passenger-Estimate Passengers Passengers Miles

Year (millions) (millions) (millions) (billions)

1972 209.9 191.3 16.6 3.01973 211.9 202.2 16.9 3.81974 213.9 207.5 18.7 4.51975 216.0 205.1 17.4 3.91976 218.0 223.3 18.2 4.21977 220.2 240.3 19.2 4.31978 222.6 274.7 18.9 4.01979 225.0 316.9 21.4 4.91980 227.2 296.9 21.2 4.61981 229.5 286.0 20.6 4.81982 231.7 294.1 19.0 4.21983 233.8 318.6 19.0 4.21984 235.8 344.7 19.9 4.61985 237.9 382.0 20.8 4.81986 240.1 418.9 20.3 5.01987 242.3 447.7 20.4 5.21988 244.5 454.6 21.5 5.71989 246.8 453.7 21.4 5.91990 249.5 465.6 22.2 6.11991 252.2 452.3 22.0 6.31992 255.0 475.1 21.3 6.11993 257.8 488.5 22.1 6.21994 260.3 528.8 21.8 5.91995 262.8 547.8 20.7 5.51996 265.2 581.2 19.7 5.01997 267.8 594.7 20.2 5.21998 270.2 612.9 21.1 5.31999 272.7 635.4 21.5 5.32000 284.9 665.5 22.5 5.5

Source: Airline statistics from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Department of Transportation. Amtrakstatistics from Background on Amtrak, GAO studies, and Amtrak annual reports.

Amtrak projections of future ridershipincreases have been wrong for years. A GAOstudy noted that in 1974 Amtrak had toldCongress it anticipated ridership in 1979would be a stunning 37 million;9 4 it turnedout to be 21.4 million passengers. Morerecently, Amtrak asserted that it would boostridership by 4.4 million passengers in FY2002, a 21 percent gain from FY 1998 traf-fic.95 Although more modest than previousstatements, it is nonetheless a projection thatAmtrak will fail to reach.

Credibility Crisis # 3: On-TimePerformance

Amtrak acknowledged in a 1994 state-ment that the “largest single area of com-plaint” by passengers is late trains, and“improving and sustaining Amtrak’s on-timeperformance is a top priority.”96 Since, thenAmtrak has issued statements suggestingthat punctuality has improved. In 1998,Amtrak touted the best January on-time per-formance since 1981;9 7 in 1999, Amtrakboasted in a letter to the ARC that its 80 per-cent record is “still ahead” of airline perfor-

mance.98 A press release this year touted goodon-time performance for the Acela Express.9 9

Unfortunately, Amtrak’s method of calcu-lating late trains fails to reflect actual perfor-mance. Amtrak is able to report its trains asbeing more punctual than they in fact are onvirtually every route outside of the NortheastCorridor. That is because Amtrak has lardedschedules with extra time (railroaders refer tothis as “padding” or “fat”) at the end of a line.Amtrak inserts the extra time just beforecheckpoints where on-time performance iscalculated. Across most of the nation, if mea-surements were taken at a station before anofficial checkpoint, Amtrak’s record wouldbe much worse than official reports indicate.The schedule padding, combined with theabsence of Amtrak on-time calculations atintermediate stations, means many passen-gers arrive late at their destinations eventhough they were aboard “on time” trains.

For example, a train starts at station A atnoon and, after stopping at stations B, C, andD, is scheduled to arrive at station E ninehours later. In the example in Table 2, thetrain is 45 minutes late arriving at station B,

14

Amtrak is able toreport its trains asbeing more punc-

tual than they infact are on virtu-ally every route.

Table 2How Amtrak Measures Late Arrivals as “On Time”

Station

A B C D E

Scheduleddepart/arrivaltime Noon 1:30 p.m. 3:00 p.m. 6:00 p.m. 9:00 p.m.Actualarrivaltime Noon 2:15 p.m 4:00 p.m 7:15 p.m. 9:15 p.m.

Differencescheduled v.actual 0 hrs. 45 min. 1 hr. 1hr. 15min. 15 min.

Notes. Amtrak measures on-time performance at Stop E. The scheduled trip time is 9 hours exactly,and the actual trip time is 9 hours 15 minutes. The train is technically on time, even though it is latefor three of four stops.

one hour late arriving at station C and onehour and 15 minutes late arriving at stationD. Passengers traveling to or from any ofthese stations suffer. Yet between station Dand station E, which happens to be an on-time checkpoint, extra time or “fat” is builtin. It might be that at normal speeds it wouldtake an hour and a half to travel betweenthose stations. By instead scheduling threehours between those stations, Amtrak per-mits late trains to make up time and arriveonly 15 minutes late. Since “on-time” is mea-sured at point E, an Amtrak train that is latefor three of four arrivals is officially “on-time.” A long-distance train is listed as “late”only if it is 30 minutes or more behind sched-ule, and for short distance trains theallowance is 10 minutes.

Some critics might ask whether congestionin metropolitan areas or other factors meanthat trains need more time entering major citiesor stations. In fact, it takes more time for a trainto accelerate when leaving a major station thanto brake when entering one, resulting in a dif-ference of less than five minutes. Finally, anyspeed limits imposed on trains travelingthrough congested metropolitan areas willslow trains going in both directions.

How Amtrak applies this practice ofbuilding in “fat” is outlined in Table 3. Theinformation reveals the contrast between therunning time of trains leaving checkpointswhere on-time measurements will not be cal-culated (and trains are scheduled to movefairly quickly) and trains entering the samecheckpoints where on-time performance willbe calculated (and the schedules containexcessive “fat”).

The first train in the table, Amtrak’s east-bound Sunset Limited, routinely takes 45minutes when running from Los Angeles toPomona, California, a distance of only 32miles. No on-time calculation is made in thisdirection. On the westbound schedule fromPomona to Los Angeles—a checkpoint whereon-time performance is calculated on incom-ing trains—it takes 1 hour and 57 minutes.Hence, the westbound time is more than twiceas long as the eastbound time. Passengers

often are inconvenienced waiting for late west-bound Sunset Limited trains in one commu-nity after another, but official reports mayshow their particular train as being “on time.”

Amtrak’s already poor on-time record of56 percent for long-distance trains in FY20001 0 0is not credible. The figure representsperformance at a few dozen checkpoints,which means trains serving hundreds of non-checkpoint stations are running significantlybehind schedule yet are never officially regis-tered as “late.”

Credibility Crisis # 4: Freight and ExpressProgram

Amtrak, which was set up as a passengerrailroad, established a new line of business in1997 as it started to carry freight and expressin boxcars or in special highway trailersattached to passenger trains. The railroadsaid the effort was designed to help it “reachits financial goals,”1 0 1become “profitable,”1 0 2

and “improve the financial performance ofpassenger trains and help preserve andexpand our network.”103

Amtrak strained credibility from the pro-gram’s inception by claiming it was moving“freight/express” and “specialty commodi-ties—computer chips, for example.”104 Whenthe news media revealed that Amtrak wascarrying boxcar loads of beer, steel, and othercommodities, Amtrak responded by claimingsuch moves were “occasional and experimen-tal.”105 Eventually, Amtrak conceded it wasmoving shipments that traditionally havebeen considered freight.

By 1998, traffic was below projections andapproximately half of the freight/expressfleet was sitting idle.106 In that fiscal year,Amtrak said it would not discuss profitabili-ty until that year’s scorecard was in,107 and itnever has. Even now, three years later, Amtrakhas yet to go on the record about whetherfreight/express adds to or takes away from itsbottom line.

Revenues generated from the new pro-gram along with revenues from Amtrak’smail-handling operation are below projec-tions. The DOT IG, in examining Amtrak’s

15

What is modern?The definitioncertainly does not mean inaugu-rating trains thatare slower thantrains weredecades ago.

Table 3Schedule “Fat” Permits Misleading On-Time Reports

Time When Times AreOn-Time Slower WhenStatistics On-TimeAre NOT Statistics Calculated ARE Amtrak’s(outbound) Calculated “Fat” in

Amtrak Train Segment under Review Miles (1997–2000) (inbound) Schedules

Sunset Limited Pomona, Ca.–Los Angeles 32 45 min. 1 hr. 57 min. 1 hr. 12 min.Sunset Limited Schriver, La.–New Orleans 55 1 hr 25 min. 2 hr. 30.min. 1 hr. 05 min.Southwest Chief Naperville, Ill.–Chicago 28 36 min. 1 hr. 36 min. 1 hr. 00 min.Texas Eagle San Marcos, Tex.–San Antonio 54 1 hr. 40 min. 2 hr. 39 min. 59 min.City of New Orleans Hammond, La.–New Orleans 52 1 hr. 03 min. 2 hr. 57 min.Three Rivers Hammond, Ind.–Chicago 16 29 min. 1 hr. 25 min. 56 min.San Francisco Zephyr Naperville, Ill.–Chicago 28 34 min. 1 hr. 29 min. 55 min.San Francisco Zephyr Martinez–Emeryville, Calif. 25 11 min. 1 hr. 05 min. 54 min.Capitol Limited Hammond, Ind.–Chicago 16 30 min. 1 hr. 23 min. 53 min.Pennsylvanian Hammond, Ind.–Chicago 16 29 min. 1 hr. 19 min. 50 min.Southern Crescent Slidell, La.–New Orleans 37 53 min. 1 hr. 35 min. 42 min.Empire Builder Edmonds, Wash.–Seattle 18 32 min. 1 hr. 12 min. 40 min.Sunset Limited Bay St. Louis, Miss.–New Orleans 57 1 hr. 12 min. 2 hr. 51 min. 39 min.Ann Rutledge Alton, Ill.–St. Louis 27 40 min. 1 hr. 18 min. 38 min.Lake Shore Limited Hammond, Ind.–Chicago 16 32 min. 1 hr. 09 min. 37 min.Cardinal Dyer, Ind.–Chicago 29 1 hr. 12 min. 1 hr. 48 min. 36 min.Empire Builder Red Wing–Minneapolis 46 1 hr. 04 min. 1 hr. 39 min. 35 min.Southwest Chief Fullerton–Los Angeles 26 40 min. 1 hr. 14 min. 34 min.International Lapeer–Port Huron, Mich. 45 48 min. 1 hr. 19 min. 31 min.Coast Starlight Tacoma–Seattle 40 56 min. 1 hr. 25 min. 29 min.Coast Starlight Glendale–Los Angeles 5 18 min. 45 min. 27 min.Wolverine Hammond, Ind.–Chicago 16 27 min. 54 min. 27 min.Lake Shore Limited Back Bay–South Station, Boston 1 5 min. 32 min. 27 min.Illini Homewood–Chicago 24 1 hr. 10 min. 1 hr. 36 min. 26 min.Illini Du Quoin–Carbondale, Ill. 20 14 min. 40 min. 26 min.Empire Builder Glenview–Chicago 18 24 min. 50 min. 26 min.Heartland Flyer Gainesville–Fort Worth 68 1 hr. 20 1 hr. 46 min. 26 min.Texas Eagle Alton, Ill.–St. Louis 27 44 min. 1 hr. 09 min. 25 min.Cascades Seattle–Edmonds 18 51 min. 27 min. 24 min.San Joaquins Wasco–Bakersfield 26 27 min. 51 min. 24 min.Pacific Surfliner Grover Beach–San Luis Obispo 9 21 min. 45 min. 24 min.Heartland Flyer Norman–Oklahoma City 20 25 min. 49 min. 24 min.Cardinal Manassas, Va.–Washington 32 54 min. 1 hr. 18 min. 24 min.Empire Builder Vancouver, Wash.–Portland, Ore.10 27 min. 50 min. 23 min.City of New Orleans Homewood–Chicago 24 45 min. 1 hr. 08 min. 23 min.Empire Service-2 trains Buffalo–Niagara Falls, NY 23 35 min. 58 min. 23 min.Ann Rutledge Joliet–Chicago 37 50 min. 1 hr. 12 min. 22 min.Illinois Zephyr Naperville–Chicago 28 35 min. 57 min. 22 min.Silver Meteor Hollywood–Miami 13 24 min. 46 min. 22 min.Ethan Allen Express Fair Haven–Rutland, Vt. 14 22 min. 44 min. 22 min.Northeast Direct Worcester–Boston 44 59 min. 1 hr. 20 min. 21 min.

16

2001 business plan, was skeptical about pro-jections that revenue will reach $402 millionby 2003, stating: “We have disagreed withAmtrak on how quickly the mail and expressservice revenues are likely to ramp up. Forinstance, in 2000, Amtrak projected revenuesof $176 million, but its actual revenuestotaled only $122 million. We understandthat Amtrak is in the process of revising itsprojections and we will look closely at thosenumbers during our ongoing assessment.”1 0 8

Amtrak asserted that carrying freight andexpress would not interfere with passengeroperations. Yet, a comparison of 2001 trainschedules with 1997 schedules shows time

added to schedules to accommodatefreight/express shipments. In Chicago, forexample, riders are delayed aboard motion-less trains in rail yards while pokey locomo-tives shunt boxcars on and off the trains. It isdifficult to see how the freight/express pro-gram can be construed as a legitimate busi-ness to enter when doing so slows passengertrain schedules, and passengers are supposedto be Amtrak’s core business.

Credibility Crisis # 5: NonpassengerRevenues

Amtrak routinely issues glowing publicstatements about its growth in passenger rev-

Table 3 continued

Time When Times AreOn-Time Slower WhenStatistics On-TimeAre NOT Statistics Calculated ARE Amtrak’s(outbound) Calculated “Fat” in

Amtrak Train Segment under Review Miles (1997–2000) (inbound) Schedules

Capitol Limited Rockville, Md.–Washington 17 22 min. 42 min. 20 min.Silver Palm Hollywood–Miami 13 24 min. 43 min. 19 min.Illinois Zephyr Macomb–Quincy 56 48 min. 1 hr. 06 min. 18 min.State House Alton, Ill.–St. Louis 27 45 min. 1 hr. 03 min. 18 min.Capitols-#729 & 733 Santa Clara–San Jose 7 12 min. 29 17 min.Cascades Albany, Ore.–Eugene 43 43 min. 59 min. 16 min.Silver Star Hollywood–Miami 13 28 min 44 min. 16 min.Piedmont Cary–Raleigh 9 13 min. 28 min. 15 min.Vermonter Essex Jct.–St. Albans, Vt. 4 30 min. 45 min. 15 min.Maple Leaf Yonkers–New York 14 24 min. 38 min. 14 min.Capitols-#727 & 731 Emeryville–Oakland 5 10 min. 24 min. 14 min.Capitols-5 trains Davis–Sacramento 13 19 min. 33 min. 14 min.Adirondack St. Lambert-Montreal 4 13 min. 26 min. 13 min.Pere Marquette Hammond, Ind.–Chicago 16 27 min. 40 min. 13 min.Piedmont Kannapolis–Charlotte 27 28 min. 40 min. 12 min.State House Joliet–Chicago 37 50 min. 1 hr. 02 min. 12 min.Capitols-#723 & 725 Santa Clara–San Jose 7 12 min. 24 12 min.Ann Rutledge & K.C. Mule Independence–Kansas City 10 19 min. 29 min. 10 min.Cascades-3 trains Tacoma–Seattle 40 58 min. 48 min. 10 min.Cascades-3 trains Vancouver, Wash.–Portland, Ore. 10 18 min. 28 min. 10 min.Pacific Surfliner-11 trains Solana Beach–San Diego 26 33 min. 34 min.-49 min. 16 min.-1 min.Hiawatha Service-5 trains Glenview–Chicago 18 22 min. 28 min.-32 min. 10 min.-6 min.

Note: Where ranges are given, “fat” varies from train to train. Information is given for only for trains that run five days or more perweek for which schedules have been padded with 10 minutes or more.

“Amtrak’s des-perate financialsituation suggeststhat its weakerroutes should bediscontinued.”

17

enues while skirting the fact that nonpassen-ger revenues have grown and are a significantsource of revenues. Such revenues in FY 2000totaled $886 million and accounted for morethan 43 percent of Amtrak’s total rev-enues.1 0 9 Amtrak also leases portions ofright-of-way along tracks to telecommunica-tions companies, owns and operates parkinggarages, and sells souvenirs.1 1 0Such activitiesraise questions of equity. Is it good publicpolicy to expand Amtrak’s subsidized freightand express program, while it competes withthree major taxpaying motor carriers—Consolidated Freightways, Roadway Express,and Yellow Freight? Amtrak’s nonpassengerventures are a growing source of unfair com-petition with private enterprises.

Credibility Crisis # 6: Network GrowthStrategy

In October 1998, the Amtrak Board ofDirectors initiated a comprehensive assess-ment of its route system with what it called aMarket Based Network Analysis. Later, withgreat fanfare, Amtrak described the MBNAas a mechanism to find opportunities to“reduce costs and increase revenue” and“match consumer demand with an efficientoperation.”1 1 1 Amtrak also said the MBNAwould drive expansion and equipment acqui-sition to accommodate the “best and mostprofitable passenger rail service.”1 1 2 Theeffort also was designed to “increase ourprofitability.”113

Amtrak later unveiled a Network GrowthStrategy based on the MBNA, which in partcalled for service changes on 14 routes.1 1 4

Amtrak claimed: “When our NetworkGrowth Strategy is fully implemented, it willadd $255 million in revenue by 2003 andexpand Amtrak service in 21 states. . . . Aspart of that strategy, we launched the LakeCountry Limited service between Chicagoand Janesville [Wisconsin].”115

Regardless of Amtrak’s phraseology, evi-dence does not indicate that added trains justi-fied by the MBNA are meeting consumerdemand, contributing to lower costs, or increas-ing profitability. In fact, Amtrak’s new trains are

so substandard they violate Amtrak’s charter,which mandates that it provide modern railpassenger service.116 What is modern? The defi-nition certainly does not mean inauguratingtrains that are slower than trains were decadesago, which is what Amtrak is doing and is whyits prospects for success are bleak. Consider thefollowing:

• The MBNA was referenced to justifystarting Amtrak’s Kentucky Cardinalfrom Jeffersonville, Indiana (nearLouisville), to Chicago on a schedule of12 hours, 45 minutes.117 In 1925, howev-er, the Pennsylvania Railroad fromJeffersonville reached Chicago in 8hours, 40 minutes118—4 hours and 5minutes faster than Amtrak’s new train.Our great-grandparents 76 years agocould ride a “milk run,” pulled by asteam locomotive, stopping at 16 townsalong the way, and get there faster thanAmtrak, which serves only five interme-diate stops. This could be one of theslowest passenger trains in the world, a“Conestoga wagon with lights.”

• The MBNA was cited to justify the April2000 start of Amtrak’s Lake CountryLimited, which links Janesville, Wiscon-sin, with Chicago in 2 hours and 30 min-utes.119 In 1952, a Chicago and NorthWestern train from Janesville reachedChicago in 1 hour, 52 minutes120—38minutes faster than Amtrak’s new train.It is not surprising that in the first threemonths of operation an average of only10 passengers per day rode Amtrak’strain in each direction, a figure dis-missed by an Amtrak spokesman whosaid, “it takes a while to ramp things up,”and traffic is “going in the right direc-tion.”121 Those added passengers werenowhere to be found when an NBCNews Fleecing of America segment thisyear showed that only one passenger wasaboard a train with about 70 seats.122

Because of the adverse publicity, Amtrakhas since announced discontinuance ofthe train effective September 21, 2001.123

18

The Economistrecently editorial-

ized in favor ofthose who believe

that “givingAmtrak controlover something

like $12 billion incapital spending

is insane.”

By Amtrak’s own data, this train lost$512 per passenger.124

• Finally, the MBNA reportedly justifiedthe startup of Amtrak service betweenMilwaukee and Fond du Lac, Wisconsin,and between Chicago and Des Moines. InSeptember of this year Amtrak droppedplans for the Fond du Lac train becauseAmtrak found “the mail and expressbusiness isn’t there to support it.”125 Amonth earlier, Amtrak cancelled plansfor the Des Moines train as “customersnever developed for the mail and expressservice that would have formed the line’sfinancial foundation.”126

Amtrak said of the MBNA process in areport to Congress, “Amtrak can only grow byservicing markets where research—hard factsand data, not hunches, nostalgia, or historicalprecedent—indicates a strong chance for suc-cess.”1 2 7But Amtrak is ignoring hard facts topromote unjustifiable expansion plans. What“market-based analysis” could justify addingtrains on slower schedules than were in effectmany decades ago? What “research” predictedthat mail and express customers could befound for two new routes where customerswere nonexistent?

The FY 2000 Transportation Appropria-tions Act and the FY 1999 Omnibus Appropri-ations Act require the Amtrak Reform Councilto identify any Amtrak routes that might becandidates for closure or realignment. InNovember 1999 the council requested fromAmtrak “comparisons and analysis of MBNAreports with Amtrak’s normal general ledgeraccounting system and Route ProfitabilitySystem reports [and] MBNA reports and analy-ses that are being used to prepare Amtrak’sStrategic Business Plan.”128

But in its latest annual report the ARCsaid, “Until the data underlying Amtrak’sMBNA analysis are made available to theCouncil for analysis . . . the Council will notbe in a position to evaluate potential Amtrakroute closures or realignments.”129 Later thesame report said, “The Council has not yethad the opportunity to examine the MBNA

nor Amtrak’s [Network Growth Strategy]analysis and detailed, underlying marketingand traffic flow data because such informa-tion had not been made available to theCouncil until very recently, and the datarecently provided may not be available in suf-ficient detail to permit the kind of compre-hensive analysis that is necessary before routechanges are suggested.”130

Anthony Haswell, an advocate for modernpassenger train service, filed suit againstAmtrak in the U.S. District Court inWashington on July 30, 2001, under the fed-eral Freedom of Information Act to force it todisclose financial information on its individ-ual train routes and services. He requestedthis information from Amtrak in April 2000under FOIA, and Amtrak has refused to com-ply. Haswell said:

Amtrak’s desperate financial situa-tion suggests that its weaker routesshould be discontinued and avail-able resources concentrated on ser-vices with long-term potential. Inorder for the government and thepublic to make informed decisionson the future of Amtrak and interci-ty rail passenger service, the informa-tion I have asked for is essential.Amtrak is spending many millionsof federal tax dollars each year subsi-dizing the operation of trains whichare slower than those of 60 years agoand which do not run on time. Thisexpensive charade must end.131

The MBNA process is a failure. Evidence isgrowing that the MBNA is a fig leaf to justifyadding trains through more congressionaldistricts in a blatant attempt to distributemore pork-barrel expenditures, a concern rein-forced by Amtrak’s uncooperative responsesto MBNA inquiries.

Credibility Crisis # 7: High-Speed RailBond Proposals

Two federal initiatives have been proposedto bring about intercity “high-speed” trains to

19

Indications arethat Amtrak’shigh-speed trainplans will drawonly an infinitesi-mal number ofpassengers fromother modes oftransportation.

America: the High Speed Rail Investment Actof 2001 and the Rail Infrastructure Develop-ment and Expansion Act for the 21st Century,or RIDE-21, a $71 billion legislative packagefor various rail projects. But neither proposalwould likely succeed outside of the NortheastCorridor where Amtrak’s Acela Express pro-gram is underway.

The High Speed Rail Investment Act of 2001.This legislation would allow Amtrak to float$12 billion in bonds to raise capital over a 10-year period to establish high-speed rail pro-grams. Bondholders would receive tax creditsrather than interest payments. Amtrakwould be required to pay back only the prin-cipal on those bonds and participating stateswould furnish at least 20 percent in match-ing funds to support a project.

While Amtrak dangles promises of “BulletTrains” to an unsuspecting public, the actwould permit Amtrak to spend billions ofdollars on trains that will remain rather ordi-nary. In cases where an Amtrak train amblesalong at 40 mph, it will be able to use bondfunds to bring the speed up to 50 mph. Theresult of this “high-speed” rail program inmany cases would be yet more Amtrak trainsrunning no faster than those run by privaterailroads decades ago. Billions of dollarswould be wasted. It is little wonder that TheEconomist recently editorialized in favor ofthose who believe that “giving Amtrak con-trol over something like $12 billion in capitalspending is insane.”132

Quite questionable is the claim by Amtrakvice chairman Michael S. Dukakis thatfuture Amtrak “high-speed” trains will easeaviation congestion, or “winglock.”1 3 3 Whatis considered “high-speed” on Amtrak doesnot qualify for that label in other parts of theworld. Even the Acela Express is hardly high-speed by international standards.1 3 4

The legislation has many other problems:

• Amtrak maintains that the tax credit willcost the U.S. Treasury only $3.3 billionover 10 years.135 But the GAO estimatesthe cost to be between $16.6 billionand $19.1 billion (in nominal dollars)

over 30 years. This is because the bondsare for 20 years and if Amtrak issuesbonds at the end of the 10-year period,the period of revenue losses would be30 years. Also disagreeing with Amtrakis the Congressional Budget Office,which found “the tax-credit fundingmechanism would essentially be a newand more expensive way for the federalgovernment to assist Amtrak.”136

• The $12 billion would cover only a frac-tion of the cost of 10 federally desig-nated high-speed routes, warned theGAO. The total cost would be closer to$100 billion.1 3 7 The ARC said fundingof this magnitude “should not logicallybe under the control of Amtrak as itexists today.”1 3 8

• The DOT IG stated that potential costsfar exceed funds proposed: “If the bondbill or a similar funding instrumentwere to be adopted, it should be clearto all parties that the $12 billion pro-vided to Amtrak would just be theproverbial ‘drop in the bucket.’. . . Thecost for developing a high-speed railprogram in each of the 10 designatedcorridors would run into the tens ofbillions of dollars. Careful considera-tion should be given to where theremaining funding would come from,as well as the likely return on invest-ment, as a precursor to Amtrak invest-ing in any of these corridors. Absentsuch analysis, it is plausible that thecountry could find itself with 10 par-tially built corridors that, in additionto the Northeast Corridor, will eachboast a multibillion dollar price-tag forcompletion.”139

By incorporating tax-credit costs on TreasuryDepartment ledgers, the $12 billion in bondscreates massive subsidies that will be off thebooks for Amtrak. Such deception freesAmtrak to again claim financial “success”despite the continuing drain on taxpayers.On a related point, the GAO estimates that“The cost of the tax credits to the U.S.

20

Amtrak misleadsthe public by say-

ing its subsidiesare “low”

compared to gov-ernment expendi-

tures for othermodes of trans-

portation.

Treasury under the bond approach would beat least $400 million greater and could bemore than $3 billion greater (in present valueterms) than providing annual appropriationsof an equivalent amount.”140 In other words,it would be less costly to simply give Amtrakthe money than to use the bond approach.

• As the GAO observed, the $12 billion leg-islation neither directs Amtrak to “segre-gate bond proceeds from other funds”nor prohibits “the possibility that bondproceeds would be available to Amtrakfor other purposes, including priordebt.”141 Amtrak is still a candidate forbankruptcy, thus concerns aboutAmtrak’s stability and use of additionalfunds should not be taken lightly.

• Amtrak will likely exploit the liabilityfor bond repayments by claiming thecost is an obligation that should bepaid by the federal government in a liq-uidation. Thus the program givesAmtrak leverage with which to argueagainst liquidation, which in turnwould perpetuate the operation ofslow long-distance trains, the antithe-sis of what the legislation is supposed-ly designed to accomplish.

• The railroad cannot be entrusted toexercise proper due diligence in fundexpenditures or project completion,and considering its flirtation withbankruptcy a logical conclusion is thatthe bill sets the stage for another multi-billion-dollar federal Amtrak bailout.

From a transportation perspective, theAmtrak program grossly exaggerates thebenefits of its high-speed trains. Consider:

• Only a small portion of the $12 billionbond proceeds may finance construc-tion of any significant high-speed railinfrastructure. Amtrak has politicizedhigh-speed rail by endorsing proposalsto run those trains where virtually nomarket exists, such as from Texarkana,Arkansas, to Dallas. Such “pet projects”

would spend bond funds to meet thepork-barrel needs of members ofCongress.

• Amtrak may spend funds on routesthat are excessively long, such asWashington to New Orleans, where, at1,152 miles, no train, no matter howfast, can compete with air travel. Thatfact applies in even the most train-dependent cultures in the world.

•Bond funds are likely to be spent on thin-ly populated routes, such as Chicago toOmaha. Most of the route goes throughIowa, but that state’s entire population of2.9 million is nowhere near the intenseconcentrations of people found inEuropean cities—the Paris area alone has10 million—or Japanese cities. Routes likethe “high-speed” Chicago-Omaha aredestined to be failures before the firstspike is driven.

• Indications are that Amtrak’s high-speed train plans will draw only aninfinitesimal number of passengersfrom other modes of transportation. Inparticular, it stretches credibility tobelieve that Amtrak will divert morethan a small number of air travelers totrains: it is doubtful a single flightwould be removed anywhere in thenation’s crowded aviation system.

• Amtrak’s record disqualifies it fromparticipation in planning high-speedrail projects. Consider Michigan, whereAmtrak spent $23 million in a joint fed-eral-state program to install new sig-nals on part of the Chicago-Detroitroute1 4 2and an additional $3.3 millionin TRA funding for communications,track, and bridge work. In April 2001,Amtrak activated the “high-speed” sig-nals, put souped-up locomotives on theline, and indeed cut 15 minutes fromschedules. Despite that, most Detroittrains remain slower than when the ini-tial funds were granted six years ago.

The $71 Billion Rail Legislation. A group of Houselegislators led by Rep. Don Young (R-Alaska)

21

Amtrak’s disap-pearance wouldbe insignificantoutside of theNortheastCorridor and afew other lines.

wants $71 billion over a 10-year period to buildhigh-speed rail lines through a $36 billion tax-exempt bond provision and $35 billion in directloans or loan guarantees for freight and com-muter rail lines. Even sponsors of this lavishspending recognize the futility of giving addi-tional subsidies to Amtrak and instead wouldsend money to states. “The legislation would ineffect separate the future of high-speed rail ser-vice from the future of Amtrak. . . . Amtrakwould not be eligible to apply for any of thefunding, although it could compete to be theoperator of any new train service. Some law-makers have made clear that they will opposehigh-speed rail funding that is put in Amtrak’scontrol.”143

These proponents also promise bullettrains to justify the $71 billion, but suchtrains will not result from what is anotherWashington pork-barrel program. Consider:

• Up to $7 billion would be set aside for“short lines.” These railroads are gener-ally only a few miles long, are located inrural areas, and carry a small portion ofthe nation’s freight. Passenger service islimited to historic trains, sometimespulled by steam locomotives, whichoffer excursions and entertainment.On that basis, spending billions onthose rail lines will do nothing torelieve airport and urban highway con-gestion as sponsors claim.

• The bill would not fund the construc-tion of new corridors dedicated exclu-sively to high-speed passenger trains,such as those in Japan and France. Theresult will be trains too slow to relieveair traffic congestion anywhere outsideof the Northeast Corridor.

• While the overall cost of the $71 billionlegislation has yet to be calculated byan objective party, costs would certain-ly be higher than the $12 billion pack-age and even then might be understat-ed due to similar misrepresentations.

• It is unclear how the states will financerail bonds and loans. Because many eli-gible projects will lack a positive rate of

return, it is likely that state taxpayers willbe liable for guaranteeing loan principleand incurring significant obligations toloan issuers and bond holders.