Development of photodiode via the rapid melt growth (RMG ...

Growth RMG

-

Upload

firoj-ahmed -

Category

Documents

-

view

235 -

download

0

Transcript of Growth RMG

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

1/23

Sustaining Ready-made GarmentExports from Bangladesh

NAZNEEN AHMEDBangladesh Institute of Development Studies, Dhaka, Bangladesh

ABSTRACT This paper analyses the main drivers of growth, challenges faced and performance of ready-made garment (RMG) manufacturing in Bangladesh following the abolition of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA). It provides evidence to show that both national and international MFA quotas did provide Bangladesh garments with access to guaranteed international markets.However, as shown by the rising export volumes and market shares of Bangladesh RMG over the period 2005-06, the withdrawal of MFA quotas did not impede the further development of the in-dustry in Bangladesh. This is an outcome of safeguard measures imposed against China in majormarkets such as the USA and the European Union. The paper argues nevertheless that both the government and private sector of Bangladesh should stimulate upgrading so that the removal of its preferential treatment privileges will not adversely hinder the industrys growth in future.

K EY WORDS : Textiles, garments, Asia, Bangladesh, Multi-bre Arrangement

Ready-made garments (RMG) have become the main export product of Bangladeshsince the late 1980s. Starting as a non-traditional export item in the late 1970s,RMG achieved this status of leading export within a short span of time. Whileexport earnings from the RMG industry were barely US$1 million in 1978, theyreached US$8 billion in 2006, comprising 75% of overall export earnings and 81%of manufacturing export earnings (see below). Some entrepreneurs without anyexperience in the export business started RMG production and later their successstories motivated others to enter the business (Quddus and Rashid, 2000: chs 3and 4). Both domestic and international policies have inuenced the rapid growth of the RMG industry. Moreover availability of cheap labour stimulated growth.

For the last two decades, the RMG industry has been the main source of growthof exports and formal employment in Bangladesh. According to 2005statistics, thisindustry directly employs more than 1.9 million people, comprising 40% of manu-facturing sector employment, 90% of whom are women and 90% are dominantlymigrants from rural areas and mainly coming from the poorest rural households(Afsar, 2001; Mlachila and Yang, 2004; Razzaque, 2005). The employment genera-ted in this industry is new employment rather than substituting for jobs in otherindustries (Kabeer and Mahmud, 2004: 107).

Correspondence Address: Nazneen Ahmed, Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, E-17, Agargaon,Sher e Bangla Nagar Dhaka 1207 Bangladesh Email: nahmed@sdnbd org

Journal of Contemporary AsiaVol. 39, No. 4, November 2009, pp. 597618

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

2/23

The RMG industry has faced several international and domestic challenges overthe decade from 1998 to 2008. In the international market, implementation of therules and regulations of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and preferential tradearrangements among different groups of countries are of special concern forBangladesh. In the domestic market, the challenges include lack of backward-linkageindustries (supplying inputs) for RMG, low productivity of the workers, and lack of efficient infrastructure (Mlachila and Yang, 2004; World Bank, 2005). Thus, themain export industry of Bangladesh is facing important challenges. Because theindustry has close links with the rural economy a woman RMG worker will usuallyremit two-thirds of her income to her rural home (Afsar, 2001: 133) changes to theindustry may have large welfare consequences for those who are directly andindirectly dependent on this industry as well as for the economy as a whole.

The aim of this paper is to provide an assessment of the Bangladesh RMG

industry its emergence, growth, strength and weaknesses and challenges in thepost-MFA world. The following section provides a brief description of production,export and employment of the RMG industry in Bangladesh. This is followed bydiscussions of the international and domestic drivers of the industry in Bangladesh,the domestic and international challenges and, nally, a discussion of the post-MFAexperience.

Production, Export and Employment

Bangladesh produces two broad categories of RMG products woven RMG andknitted RMG (also known as knitwear or knit RMG). These two categories usedifferent types of yarn, fabric and machineries and manufacturing technology.Even in terms of labour use, these two types of RMG factories differ. The wovenRMG sector employs mostly women workers and knitted RMG employs mostlymen. For example, Bakht and colleagues (2002: 46) found that the incidence of womens employment in the knitwear industry is only about 33%. This is because of differences in skill requirements in these two types of factories. A larger proportionof knitwear enterprises are of composite type, with a signicant degree of backward-linkage activities and are more skill intensive in nature (Bakht et al., 2002: 46), whileskilled women workers are relatively scarce in the RMG sector of Bangladesh. 1

Another reason for lower participation of women in knit factories is that they tend toincorporate a fabric-knitting section that is often operated in an overnight shift(Bakht et al., 2008: 3) and, according to the Bangladesh Labour Law (2006), womenare not allowed to work between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. (Bakht et al., 2008: 3).

Emergence and Growth

As noted above, since the early 1980s, the RMG industry of Bangladesh has grownat a very fast pace in terms of export value and share in total export (Table 1). Sincethen, the composition of export has also changed. The most obvious change is thatraw and processed jute exports that were dominant in the early 1980s have been

displaced by RMG exports. While the RMG (woven and knitted together) industrycontributed only 0.4% to total export earning in the scal year 1980/81, itcontributed 75 1% in 2005 06 It is evident from Table 1 that RMG export growth

598 N. Ahmed

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

3/23

acted as the main force behind total export growth for Bangladesh. Othermanufactured goods also show a steady growth. This category includes lightengineering, chemical, agro-processing and electronics, but these remain infantindustries and are not in a position to become substitutes for RMG. During theperiod 1990-2006, RMG grew at an average annual rate of 19%, while non-RMGexport and GDP growth rates were 8% and 5%, respectively.

Initially Bangladesh was producing and exporting only woven RMG. From theearly 1990s production and exports of knitted RMG started and experienced robustgrowth (Table 2). While the share of knitted RMG was 15.1% in total RMG exportearning in 1990-91, it became 48.3% in 2005-06. Over the years the number of RMGfactories rose from 134 in 1983/84 (Zohir, 2001: 138) to 5990 (1500 knitwear and4490 woven) in 2008 (Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Associa-tion, 2008; Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association, 2008).

One important consequence of rapid growth of the RMG industry is the growth of

employment in this labour-intensive industry. As seen in Table 3, employment in theindustry grew from 0.2 million people in 1985-86 to 1.9 million in 2005. As has beenmentioned above a feature of this employment is the employment of women as

Table 1. Structure of exports, Bangladesh (US$ million)

Items 1980-81 1990-91 1999-2000 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06

Primary goods 209(29.4)

306(17.8)

469(8.2)

485.8(6.4)

648(7.49)

773(7.3)

Raw jute 119(16.8)

104(6.1)

72(1.3)

79.7(1.1)

96(1.11)

148(1.4)

Tea 41(5.8)

43(2.5)

18(0.3)

15.8(0.2)

16(0.18)

12(0.11)

Frozen food 40(5.6)

142(8.3)

344(6)

390.3(5.1)

421(4.86)

459(4.4)

Other primarygoods

9(1.3)

17(1.0)

35(0.6)

67(0.89)

116(1.34)

154(1.5)

Manufacturedgoods

501(70.6)

1411(82.2)

5283(91.8)

7117.2(93.6)

8006(92.51)

9753(92.6)

Jute goods 367(51.7)

290(16.9)

266(4.6)

246.5(3.2)

307(3.55)

361(3.4)

Leather & leathergoods

57(8.0)

136(7.9)

195(3.4)

211.4(2.8)

221(2.55)

257(2.4)

Woven garments 3(0.4)

736(42.9)

3083(53.6)

3538.1(46.5)

3598(41.58)

4084(38.8)

Knitted garments 0(0.0)

131(7.6)

1270(22.1)

2148(28.3)

2819(32.58)

3817(36.3)

Chemical products 11(1.5)

40(2.3)

94(1.6)

121(1.60)

197(2.28)

206(2.0)

Other manufacturedgoods

63(8.9)

78(4.5)

375(6.5)

973.2(12.8)

652(7.53)

1028(9.8)

Total export 710(100) 1717(100) 5752(100) 7603(100) 8654(100) 10526(100)

A year is noted here as the scal year of Bangladesh, which starts on the 1 July; gures in parentheses referto percentage share.Source : CPD (2001) and Economic Review (2007).

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 599

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

4/23

T a

b l e 2

. E x p o r t v o l u m e a n d g r o w t h o f R M

G , 1

9 9 0 - 9 1 t o 2 0 0 5 - 0

6 ( U S $ m i l l i o n a n d % )

Y e a r

K n i t t e d R M G

e x p o r t s

W o v e n R M G e x p o r t s

T o t a l R M G

e x p o r t s

V o l u m e

A n n u a l g r o w t h

o f R

M G ( % )

V o l u m e

A n n u a l

g r o w t h ( % )

S h a r e i n t o t a l

R M G e x p o r t ( % )

V o l u m e

A n n u a l

g r o w t h ( % )

S h a r e i n t o t a l

R M G e x p o r t ( % )

A

n n u a l

g r o w t h ( % )

1 9 9 0 - 9 1

1 3 1

1 5 . 1

3

7 3 5

8 4 . 8 7

8 6 6

1 9 9 1 - 9 2

1 1 8

9 . 6

2

9 . 9 8

1 0 6 4

3 0 . 9

9 0 . 0 2

1 1 8 2

2 6 . 7

1 9 9 2 - 9 3

2 0 4

4 2 . 2

1 4 . 1

3

1 2 4 0

1 4 . 2

8 5 . 8 7

1 4 4 4

1 8 . 1

1 9 9 3 - 9 4

2 6 4

2 2 . 7

1 6 . 9

8

1 2 9 1

4 . 0

8 3 . 0 2

1 5 5 5

7 . 1

1 9 9 4 - 9 5

3 9 3

3 2 . 8

1 7 . 6

4

1 8 3 5

2 9 . 6

8 2 . 3 6

2 2 2 8

3 0 . 2

1 9 9 5 - 9 6

5 9 8

3 4 . 3

2 3 . 4

9

1 9 4 8

5 . 8

7 6 . 5 1

2 5 4 6

1 2 . 5

1 9 9 6 - 9 7

7 6 3

2 1 . 6

2 5 . 4

3

2 2 3 7

1 2 . 9

7 4 . 5 7

3 0 0 0

1 5 . 1

1 9 9 7 - 9 8

9 4 0

1 8 . 8

2 4 . 8

5

2 8 4 3

2 1 . 3

7 5 . 1 5

3 7 8 3

2 0 . 7

1 9 9 8 - 9 9

1 0 3 5

9 . 2

2 5 . 7

5

2 9 8 4

4 . 7

7 4 . 2 5

4 0 1 9

5 . 9

1 9 9 9 - 2 0

0 0

1 2 6 9

1 8 . 4

2 9 . 1

7

3 0 8 2

3 . 2

7 0 . 8 3

4 3 5 1

7 . 6

2 0 0 0 - 0 1

1 4 9 6

1 5 . 2

3 0 . 7

9

3 3 6 3

8 . 4

6 9 . 2 1

4 8 5 9

1 0 . 5

2 0 0 1 - 0 2

1 4 5 9

7 2 . 5

3 1 . 8

4

3 1 2 4

7 7 . 7

6 8 . 1 6

4 5 8 3

7 6 . 0

2 0 0 2 - 0 3

1 6 5 3

1 1 . 7

3 3 . 6

6

3 2 5 8

4 . 1

6 6 . 3 4

4 9 1 1

6 . 7

2 0 0 3 - 0 4

2 1 4 8

2 9 . 9

3 7 . 7

8

3 5 3 8

8 . 6

6 2 . 2 2

5 6 8 6

1 5 . 8

2 0 0 4 - 0 5

2 8 1 9

3 1 . 3

4 3 . 9

2

3 5 9 8

1 . 7

5 6 . 0 6

6 4 1 8

1 2 . 9

2 0 0 5 - 0 6

3 8 1 6

. 9 8

3 5 . 3

8

4 8 . 3

1

4 0 8 3

. 8 2

1 3 . 5

0

5 1 . 6 9

7 9 0 0

. 8 0

2 3 . 1

0

S o u r c e :

E P B ( v a r i o u s y e a r s ) .

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

5/23

workers, who account for 90% of the employees in the RMG industry (Mlachilaand Yang, 2004: 6). Also, 90% of the workers are migrants from the rural areas

(Afsar, 2001: 96). Employment in this industry has made women visible in natio-nal employment statistics and has brought about a social change (Zohir, 2001).A factory job may be counted as one of the few socially acceptable ways foruneducated or low-educated women to earn a living. In rural Bangladesh women livein a traditional atmosphere, which does not permit them to go to cities alone (evenoutside the village in some cases). Rural women, largely, remain outside the purviewof the visible cash economy, being primarily functional in the domestic and informaleconomies. Thus, it is quite a new development that a large number of women aregoing to work in the city-based RMG factories, inevitably changing their status andeconomic signicance.

There are both international and domestic reasons for the growth of the RMGindustry in Bangladesh. Domestically, export-promoting policy changes in generaland some policies specic to the RMG industry contributed to a large extent to therapid growth of this industry. Moreover, the availability of cheap workers stimulatedthe growth of the industry. These international and domestic reasons for the growthof the RMG industry in Bangladesh are discussed in the following sections.

Drivers of RMG Export

International Drivers

Internationally Bangladeshs RMG industry ourished under the umbrella of theMulti-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) on textile and RMG trade. The rst MFA wasdevised in 1974 and provided for rules and the imposition of import quotas, eitherthrough bilateral agreements or unilateral actions, on trade in textiles and RMGbetween individual developed country importers and developing country exporters. 2

Though the quota imposed by the importing country should restrict the exports of the exporting country, it helped the growth of the RMG industry in many develop-ing countries like Bangladesh. As shown in Table 4, this was due to the zero or lowrates faced by exports from Bangladesh to the USA and the European Union (EU).Relatively less restrictive import quotas for Bangladesh under the MFA compared to

traditional RMG exporters (such as Korea, Hong Kong, Japan and China) ensureda market for Bangladesh RMG in the USA and stimulated growth of the RMGindustry (Bhattacharya and Rahman 2000)

Table 3. Employment in the RMG industry of Bangladesh

Year Employment (million)

1985-86 0.21990-91 0.41995-96 1.31999-2000 1.62001-02 1.82004-05 1.9

Source : Mlachila and Yang (2004: 7) and Razzaque (2005: 9).

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 601

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

6/23

During this period, political problems in Sri Lanka and the anti-export environmentin India the two major South Asian RMG producers until the early 1980s inducedbuyers to shift attention to Bangladesh (Spinanger, 2000). Another importantstimulant for the growth of RMG in Bangladesh was the tariff and import quota-freeaccess in the EU under the Generalised System of Preference (GSP) scheme, whichcontributed to the expansion of RMG exports in the EU market provided thatBangladesh met the rules of origin (ROO) requirement. The GSP scheme allowed EUimporters to claim full tariff drawback on imports when they import from Bangladesh(Bhattacharya and Rahman, 2000). On average, the tariff rate of RMG products in theEU is 12.5%, but was zero for Bangladesh under the GSP. Such a preferentialtreatment made the EU the largest RMG export market for Bangladesh.

Domestic Drivers

After achieving independence in 1971, the trade and investment policies promoted animport-substituting growth strategy. This implied the emergence of large-scale publicsector enterprises, widespread quantitative restrictions on imports, high importtariffs, foreign exchange rationing and an overvalued exchange rate. The result wasan anti-export bias, scal imbalances and lack of incentives for industrialisation.Since the early 1980s, to enhance economic growth, the government initiated steps toderegulate, decontrol and liberalise the economy. As a result of various liberalisationpolicies and reforms under the Structural Adjustment Programmes, average nominaltariff rates in Bangladesh came down from 89% to 17% during 1992-2000 andfurther to 13.4% in 2006 (CPD, 2001; Economic Review, 2007). Easy access toimported raw materials and incentives for export-orientated activities helped reducethe anti-export bias in Bangladesh and encouraged export-orientated investments.

The main export incentives received by the RMG industry are shown in Table 5.In 1980, the RMG producers were granted back-to-back letter of credit (L/C) andbonded warehouse facilities. As a result they achieved tariff-free access to inputs and

thus required less working capital. Foreign exchange liberalisation that allowed forconvertibility of the Bangladesh currency (taka) also stimulated imports of inputsand RMG exports

Table 4. Export tax equivalents of import quotas in selected countries, 2003 (as a % of f.o.b.prices net of quota price)

Textiles RMGsUSA EU USA EU

Bangladesh 0.0 0.0 7.6 0.0India 3.0 1.0 20.0 20.0China 20.0 1.0 36.0 54.0Pakistan 9.8 9.4 10.3 9.2

Estimates are based on the quota price information for countries other than India. For India estimates areinterpolated from quota utilisation data. For more on export tax equivalents (ETEs), see Francois andSpinanger (2000).Source : Mlachila and Yang (2004: 14).

602 N. Ahmed

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

7/23

In addition, as mentioned above, the availability of low-wage workers is a majorcompetitive advantage for Bangladesh. In 2003, the wage per worker in Bangladeshwas 157% lower than in China. Comparing Bangladeshs 1997 data with 1998 data forIndia we also observe that wage per worker in Bangladesh is 20-30% lower (Table 6).As noted earlier, these workers are mostly young unmarried women, migrating rstfrom rural areas and maintaining a close link with the rural economy. The seeminglyunlimited supply of this labour, makes it easy to employ them at a low wage.

Challenges Faced by RMG Manufacturing

Despite the long period of rapid growth, the RMG industry in Bangladesh faces anumber of challenges. For example, dependence on imported inputs, product andmarket concentration, lacking backward linkages, possible trade diversion from

various regional trade agreements, production of low value-adding products, labourcompliance, infrastructure constraints are some of the challenges faced by thisindustry

Table 5. Main export incentives for RMG

Incentive Details

Duty drawback The tariffs paid on imported inputs and the value-added taxpaid on local inputs used for export products are refunded.All export-orientated production units not enjoying bondedwarehouse facilities have access to the tariff drawback.

Bonded warehousefacilities (BWF)

A rm can delay the payments of tariffs until they are ready toconsume inputs imported earlier and if these inputs are usedfor producing export products then they are not required topay the tariff. However, if these inputs are used to produceproducts to be consumed domestically, then producers haveto pay the tariffs for the imported inputs. Moreoverproducers can maintain un-utilised stocks without payingtaxes/tariffs, thereby reducing the total cost of holdinginventories. Also, under the BWF, an export industry canget back any import tariff they already paid for importedinputs.

Cash incentives Under the cash compensation scheme, domestic suppliers toexport-orientated RMG factories used to receive a cashpayment equivalent to 10% of the value addition of theexported RMG. In 2008, the sector continued to receive a5% cash incentive.

Back-to-back letters of credit (L/C) facilities

Under the L/C extended by commercial banks, exporters areable to import inputs (fabrics and accessories) against theexport orders placed in their favour by the nal RMGimporters. Thus, by showing the export order exporters can

get credit from commercial banks to pay for importedinputs. The payment for the export of the nal good can becleared by the exporter after they pay back the credit to thecommercial banks. This provision allows Bangladeshsexporters to avoid investing their own resources to nanceworking capital.

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 603

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

8/23

Dependence on Imported Inputs

Most of Bangladeshs RMG exports are made from imported textiles. Bangladesh isa net importer of textiles and a net exporter of RMG. Ultimately there is a tradesurplus from the combined textile and RMG trade. In 2002, Bangladesh importedUS$1.8 billion of textiles and related inputs and the trade surplus was US$2.8 billion(Mlachila and Yang, 2004: 7). The domestic textile industry cannot full the growingneed for the raw materials needed in the RMG industry. There are three differenttypes of RMG manufacturers in Bangladesh: (1) integrated manufacturing, wherefactories import the cotton and do the rest of the production process (spinning,weaving/knitting, cutting and sewing) on their own; (2) factories importing yarn andthen completing the rest of the manufacture; and (3) factories importing fabric andsewing the RMG, known as cut, make and trim (CMT) factories (World Bank,2005). Most of the knitted RMG-producing factories in Bangladesh belong to therst two categories and woven RMG-producing factories belong to the thirdcategory. Thus, knitted RMG is relatively less dependant on imported raw materialscompared to the woven RMG industry. While 85% of the fabric used in wovenRMG is imported, this is only 25% of the yarn and fabrics used in knitted RMG(World Bank, 2005). Because of the type of machines and manufacturing technologyrequired, huge investment is required for setting up factories producing fabrics forwoven RMG. As a result, local fabric production is not enough to meet the demandof woven RMG and, therefore, woven RMG is highly dependent on importedfabrics. Local spinning mills are mostly producing yarn for local knitting mills and,from this yarn, fabrics for knitting RMG are produced. The main reason for betterintegration in knitting RMG is the requirement of relatively low investment andsimpler manufacturing technology. For example, a knit fabric manufacturing, dyeingand nishing unit of a minimum economic size requires an investment of aboutUS$3.5 million, while the investment requirement for a woven fabric manufacturing,dyeing and nishing unit of a minimum economic size is at least US$35 million

(Quasem, 2002). Textile fabrics imported in Bangladesh are used mainly in thewoven RMG industry. Other RMG industry imports include raw cotton, cotton andsynthetic yarn synthetic bre and textile accessories 3

Table 6. Wages and productivity in RMG industries, selected countries

Country Year

Yearly

value-addedper employee (US$)

Yearly wages

and salariesper employee (US$)

Bangladesh 1997 900 4002003 2500 700

China 2001 5000 16002003 7000 1800

Hong Kong SAR 1999 27,600 14,800India 1998 2600 700Indonesia 1999 2500 600Sri Lanka 1998 2500 700

Source : 2003 Bangladesh and China data are from World Bank (2005: 44) and others from Mlachila and

Yang (2004: 21).

604 N. Ahmed

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

9/23

As a result of the heavy dependence on imported inputs, value-added of the RMGindustry is quite low. For woven RMG, value-added is only 25-30% of the exportvalue (Bhattacharya and Rahman, 2000). Because of lower dependence on importedinputs, the knitted RMG industry has a higher value-added, between 40% and 60%.Thus, although the RMG industry has a share of 75% in total exports, the netexport earning (i.e. export earning net of the cost for imported raw materials usedfor the export goods) is only 40% (Bhattacharya and Rahman, 2000. Dependenceon imported inputs also prolongs the time for fullling an export order. As localtextile mills cannot meet the demand of woven RMG, fabrics for woven RMGfactories are mostly imported and, therefore, more time is required to completeproduction. This is because it is too costly for manufacturers to maintain aninventory, especially as production in woven RMG is in accordance with orders,where buyers specify the type and colour of the fabrics; at best, manufacturers keep

inventories for very basic fabrics. Setting up of a central bonded warehouse couldsolve this problem, at least to full the needs of RMG factories for regular and basicfabrics.

Product and Market Concentration

Bangladeshi factories export both woven RMG and knitted RMG. Although wovenRMG contains the larger share, the export of knitted RMG has grown faster (seeTable 2). However, the RMG export from Bangladesh is highly concentrated on afew products. Only ve categories comprised almost 85% of total RMG exportsin 1997 (Islam, 2001). Ahmed (2005) noted that nine categories constituted 60%of Bangladeshs RMG export to the USA in 2004. Islam (2001) calculates thatthe product concentration of Bangladeshi RMG exports is much higher than forIndia and China. Moreover, Bangladeshs RMG exports are concentrated in twomarkets the EU and the USA. These two markets together comprise 94% of Bangladeshs total RMG export (Table 7).

Import quotas under the MFA, which stimulated the growth of the RMG industryin Bangladesh, were abolished on 1 January 2005. The abolition of quotas was

Table 7. Share of exports of Bangladeshs RMG to different markets, 2001-03 (%)

Markets

Woven RMG Knitted RMG Totals

2001/02 2002/03 2001/02 2002/03 2001/02 2002/03

EU 44.5 47.7 69.9 73.1 52.6 56.3USA 51.0 46.6 25.0 21.2 42.7 38.0Canada 2.0 2.9 2.4 2.9 2.1 2.9Norway 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.8 0.5 0.6Switzerland 0.4 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.5 0.6Korea 0.1 0.1 0 0 0.1 0.1Japan 0.4 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.4 0.3Australia 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1

Others 1.1 1.1 1.1 1.2 1.0 1.1Totals 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

S EPB (2002/03)

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 605

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

10/23

undertaken under the Agreements on Textile and Clothing (ATC) of the WTO.In 1995, the ATC replaced the MFA, which had governed the trade in textile andRMG until the end of the Uruguay round in December 1994.

Removal of MFA import quotas has generated doubts about the future growth oreven survival of the RMG industry in Bangladesh and in many other least developedcountries (LDCs). The possible impacts of phasing out of textile and RMG importquotas have received attention in a number of studies (e.g. Diao and Somwaru, 2001;Hertel et al., 1996; Lips et al., 2003; Mlachila and Yang, 2004; Nordas, 2004; Yanget al., 1997). In general, these studies concluded that phasing out of MFA wouldresult in an increase in world trade of RMG and a decrease in consumer prices.At the same time, it was noted that the impacts would vary between countries.In the case of Bangladesh, pessimistic predictions were made in studies by Lips andcolleagues (2003) and Mlachila and Yang (2004).

Until the end of MFA, Bangladesh was facing import quotas only in the USA,while import quotas and tariff restrictions in other markets had been removedalready. The quota-restricting countries/regions were the USA, EU, Canada andNorway. Under the GSP scheme, Bangladesh did not face any restrictions in theEU; Norways import quotas had been removed while its tariffs on exports fromLDCs were removed in 2002, and Canada allowed tariff and import quota-freeaccess for LDCs from January 2003. While Bangladesh received both import quotaand tariff exemptions in major restricted markets, many of its competitors stillfaced tariff and import quota restrictions. This preference gave Bangladesh anadvantage over its competitors in those markets. With the removal of importquotas, Bangladesh was expected to face increased competition both in theUSA and the EU. In the USA, because there is no tariff preference, import quota-free competition may move Bangladesh out of this market. The effects of importquota removal mainly depended on how restricted were the exports of a countryunder the MFA import quota regime in absolute terms and relative to thecompetitors. Bangladesh still faced import quota restrictions in the USA in 30items, while 69% of RMG imports from Bangladesh were under import quotas in2001-02.

Mlachila and Yang (2004) have noted that in 2002 Bangladesh was the secondmost export-restricted Asian country after China. Although they also pointed outthat in 2003 and in early 2004 the export tax equivalents (ETEs) of quotas forBangladesh fell strongly compared to its competitors it can be argued that theremoval of quotas facing China and India could have a negative impact on exportsfrom Bangladesh because of the similarity of exports from these countries. Theexport similarity index calculated by Mlachila and Yang (2004) identies China andIndia to be exporting similar products as Bangladesh to the USA and Pakistan to theEU (Table 8).

To predict the possible consequences of abolition of MFA import it is useful tolook into the domestic resource cost (DRC) of RMG production in Bangladesh.The free-on-board (f.o.b.) price of RMG can be considered as an indicator of DRC.Table 9 presents the f.o.b. price of a 180 g T-shirt in different countries as calculated

by the World Bank (2005). The f.o.b. price of RMG products (without any costof quota) from Bangladesh is higher than the price of similar products in Indiaand China but lower than in Nepal Thus after quota abolition when all countries

606 N. Ahmed

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

11/23

are treated in the same manner, it is considered that the competitive position of Bangladesh could deteriorate.

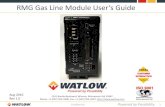

Looking further into the cost structure of the same 180 g T-shirt, it can beobserved from Figure 1 that the cost of material is the major cost component,accounting for 78% of the total cost, which is mainly expended on imported cottonfabrics (93% of total material cost). Labour and administrative costs come next.

Besides import quotas, RMG products from Bangladesh face high importtariffs (15-20%) in the USA. The estimates of Razzaque (2005: 133) suggested thattariff-free access to the USA could increase exports of Bangladesh by US$530million.

The EU and Rules of Origin

Textile and RMG export from Bangladesh has enjoyed preferential market access inthe EU under the GSP since the early 1980s, allowing tariff and import quota-free

Table 8. Export similarity index, Bangladesh and its main competitors, 2002 (%)

Markets USA EU

ExportersChina 71.5 22.0India 57.1 39.1Pakistan 34.8 67.6

The Finger-Kreinin Similarity Index can range from zero to 100 and higher values indicate greatersimilarity in exports between the considered countries. The index is sensitive to the product aggregationlevel.Source : Mlachila and Yang (2004).

Table 9. Free-on-board price comparisons, 2004 (US$)

Bangladesh China India Nepal

F.o.b. price of 180 g T-shirt 1.3 0.9 1.2-1.5 2.0

Source : World Bank (2005).

Figure 1. Cost structure for producing a 180 g T-shirt in Bangladesh, 2004. Source : Adaptedf W ld B k (2005 41)

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 607

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

12/23

entry to this market. In contrast, many competitors of Bangladesh faced importquota restrictions in this market (see Table 6). Among others facing the importquotas are China, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam.Many also faced tariffs at an average rate of 12.5%. Therefore, post-MFA com-petition in the EU was considered to be more intense than in the USA, althoughsome took a contrary position. 4 As its competitors received import quota-freeaccess to the EU market, the existing preferential position of Bangladesh could bereduced.

Moreover a heavily import-dependent Bangladesh RMG industry was noted tond it difficult to full the EUs ROO requirement. Although there is no importquota restriction, exports from Bangladesh face restrictions in the form of the ROOrequirement in the EU market. Failure to meet this requirement would cause RMGproducts of Bangladesh to face 12.5% tariff, as faced by non-LDCs. Bangladesh

faces two-stage ROO in the cases of both knitted and woven RMG.5

For somewoven products one-stage ROO is allowed when the value of the imported inputdoes not exceed a certain limit (usually 40-9%) of the ex-work price of the product.Thus, the ROO requires 51% domestic value-added for any product. This is oftendifficult, especially for woven RMG, as woven RMG is heavily dependent onimported inputs (section 3). The knitted RMG industry can meet this ROOrequirement, as the value-added in knitted RMG is higher (around 60%, accordingto Bhattacharya and Rahman, 2000).

Since 2001 Bangladesh, as an LDC, is included under a special arrangement of EU-GSP known as the Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative. However, as theROO provision remains the same under EBA as it is in the GSP, there is no extrabenet for Bangladeshs RMG industry under this amendment. It was expected thatthe EU would soften the ROO criteria under its new GSP scheme for the period2006-15. However, the ROO criteria have remained the same in the new GSPscheme. Now the change is expected to evolve under the so-called regionalcumulation or South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC)cumulation. In 2000, EU-GSP allowed SAARC member countries the possibilityof a regional cumulation (Rahman and Bhattacharya, 2000: 6). Under this, themembers of SAARC are eligible to receive special ROO treatment if they meet acertain value-added criterion. According to this treatment, a product of a country ina regional group, which is then processed in another country in that group, will beconsidered as the product of the country where the nal processing took place.However, the value-added in the nal processing has to be higher than highestcustoms value of the products used originating in any of the other countries of thegroup. As the local value-added of the Bangladesh RMG, especially thewoven RMG, is only 25-30%, Bangladesh is unable to benet from this regionalcumulation facility. For example, if fabrics are imported from India and the localvalue-added is 25% and the value added by India is 75%, the EU will consider theproduct as originating from India. The tariff on the product will be the rateapplicable for India (15% tariff drawback on 12.5% tariff rate), which ismuch higher compared to 100% tariff drawback on the 12.5% tariff rate for

Bangladesh.The EUs free trade agreements (FTA) with other countries are also imposing

extra challenges for Bangladesh especially the free trade agreement between

608 N. Ahmed

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

13/23

Mexico and the EU which began on 1 July 2000. The FTA liberalised over 96% of EU-Mexico trade by 2007. As the export similarity in RMG is high betweenBangladesh and Mexico, Bangladesh was predicted to lose market share in theEU (Islam, 2001). Moreover the enlargement of the EU and the EUstarif reduction agreements with the Central and East European Countries couldhave had trade diversion effects for Bangladesh. Further enlargement of theEU might also be a threat, particularly because of the possible membership of Turkey.

Regional Preferential Trade Arrangements

Apart from the multilateral trade rules, trade in textiles and RMG can be affectedby regional preferential trade arrangements (PTAs). The effects of regional PTAs

on members and non-member countries have received attention in both thetheoretical and empirical literature (e.g. Ahmed, 2001; Krugman, 1991). Thesestudies considered both quantity and terms of trade effects of preferential tradingarrangements. The member countries of a PTA face trade creation and/or tradediversion effects, which may be welfare increasing or welfare decreasing. The non-members may be affected both in terms of quantity (exports may decline as a resultof trade diversion) and terms of trade (unfavourable to the non-members), whichmay ultimately affect the welfare of non-members. 6 If a PTA is large and it gets aterms of trade gain by reducing its trade with the rest of the world in favour of itsown members, then the rest of the world suffers a terms of trade loss (the rest of the world has to export more in order to be able to import a given bundle of goodsfrom the PTA).

Regional PTAs that are of concern for Bangladesh are the North American FreeTrade Agreement (NAFTA) and the SAARC Preferential Trading Arrangement(SAPTA), which has later been transformed to the South Asian Free Trade Area(SAFTA). NAFTA is a particular concern for Bangladesh because of the specialprivileges accorded to Mexico in the US market. The export similarity index of garment produces of Bangladesh and Mexico to the USA is as high as 68% (Islam,2001). US tariffs on RMG originating in Mexico were eliminated on 1 January1999. Eventually all tariffs on textile and RMG traded between Canada, the USAand Mexico were eliminated by 2003. However, the NAFTA preferential tariff onlyapplies to products originating from a member country. For RMG, the tripletransformation rules of origin must be met. According to this rule, the yarn, fabricand garment must be made in NAFTA countries to receive the preferential tariffsand RMG goods qualify as originating if the non-NAFTA content is 7% or less.Islam (2001) has noted that trade diversion effects caused by NAFTA can causeincreased imports from Mexico at the expense of Asian exporting countries. Whilethe impact of NAFTA is a concern for Bangladesh, another concern in the USA isthe implementation of the Trade and Development Act (TDA 2000). Under thisAct a total of 72 countries (of which 48 countries belong to Sub-Saharan Africaand the other 24 coming from the Caribbean Basin) receive tariff-free and

import quota-free access to the USA for textile and RMG products if they meetcertain eligibility criteria. TDA 2000 has two main parts: the African Growthand Opportunity Act (AGOA) and the United States Caribbean Basin Trade

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 609

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

14/23

Partnership Act (CBTPA). For the Caribbean countries it is a process of facilitating their ultimate participation in the Free Trade Area of the Americas(FTAA). In many cases they receive the NAFTA treatment for their exports. Thisact might have impacts for the RMG export from Bangladesh to the USA,especially because of preferential treatments to Jamaica and Dominican Republic,who are competitors of Bangladesh.

Although SAPTA was structured in the early 1990s and went through severaltariff reduction stages between the members, it did not have a substantialimpact. Later it was transformed into SAFTA, which is under a process of implementation. SAFTA might help to strengthen the competitiveness of Bangladeshs RMG by allowing low-cost import of inputs from the region. Thoughthere are possibilities of trade diversion effects from SAFTA, it has high potential toextend trade creation effects and other (often non-economic) benets among its

members.

Concerns over Workers Rights

Ahmed (2006) has noted a pressure to reduce price ows from nal consumers(in the importing countries) to the producers and ultimately to the workers as aresult of globalisation and increased competition. This process may encouragethe informalisation of work and make workers more exible. Thus, there may bemore sub-contracting of various parts of the production work, tasks that will bemainly done by part-time or home-based workers. It is difficult to monitor work-ing conditions at these levels of employment, which means greater possibility of violating workers rights. Ahmed has also noted another type of pressure of globalisation in the form of pressure to address workers rights. In the currentworld the issue of workers rights is largely guided by the concept of decentwork, dened by the International Labour Organisation (ILO, 1999; 2001). Thebasic concept of decent work calls for certain standards for work and the socialenvironment in which employment takes place (see, for example, Godfrey, 2003).With the rise of the decent work agenda, various social standards have evolved asindicators of the competitiveness of a country. While conventional economistsconsider that poorer countries have a comparative advantage in the productionof manufacturing goods, it is rephrased by others as an unfair advantage as theworking conditions of these manufacturing industries are often exploitative (seeKabeer and Mahmud, 2004). As a result, social standards (and also environmentalstandards) are included in various trade regulations as preconditions to receivespecial tariff preferences (e.g. The Council Regulation (EC), No. 2501/2001 of 10December 2001).

Low-cost labour is a major source of competitiveness of the RMG industry of Bangladesh. But it is observed that labour remains low cost partly because workersrights in terms of wages, overtime payment, maternity leave for women workers, job security, factory environment and so on are violated (Ahmed, 2006: 119-26).However, the increased concerns of the world market towards labour compliance

have exposed the entrepreneurs of the apparel industry of Bangladesh to thechallenge of how they can achieve a balance between price competition and investingto address workers rights

610 N. Ahmed

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

15/23

Productivity of Workers

The wage rate for RMG workers in Bangladesh is low and their productivity is alsolow. Table 6 reveals that value-added per worker in Bangladesh is lower than for itscompetitors. Based on data from 1980-92, Islam (2001) showed that labourproductivity in Bangladesh is less than half of that of India and Sri Lanka. Theaverage number of operatives per sewing machine is 2.5 to 3, in contrast with justover 1 in modern factories (Spinanger, 2000). Moreover, capital intensity is low inBangladeshs factories. The World Bank (2005) has shown that average capitalintensity per worker in RMG factories of Bangladesh is US$1500, while that of China is US$4000. Low productivity partially offsets the widely perceivedcomparative advantage of Bangladesh in terms of low wages for workers.

Production of Low Value-adding Items

Bangladesh produces low value-adding RMG items, which are supplied into the lowand medium market price quartiles in the EU and the USA. Even compared to otherexporters of similar products, the prices of Bangladeshi products are low. Islam(2001: 61) mentioned that for 11 out of 20 selected RMG categories imported to theUSA, the unit price for Bangladeshi products is lower than the world average.Bangladesh RMG is also characterised by a narrow product range producing mainlybasic tops, shirts, trousers and unstructured jackets (Gherzi Report, 2002).

Infrastructure BottlenecksThe World Bank (2005) has identied infrastructure bottlenecks, along withcorruption and the high cost of nance, as one of three main sources of comparativedisadvantage for Bangladeshs export industries. Infrastructure bottlenecks andinefficiencies in terms of electric power, gas, port facilities and telecommunicationsnegatively impact exports from Bangladesh (including RMG) and this reduces thecompetitiveness of exporters. All these hamper the quality of production, increasecost and extend lead times. In a competitive world, buyers prefer to source productsfrom suppliers that can deliver products fast. In Bangladesh the lead time for RMGexport varies between 120 and 150 days, whereas the corresponding time for SriLanka is 19-45 days and for India just 12 days for similar products (Bhattacharyaand Rahman, 2000).

The cost of making up for inadequate infrastructure can be high. For example, asa result of a lack of reliable electric power supplies, most factories maintain theirown generator, which is relatively costly (2.5 times the cost of getting power from thegrid) and adds to the price of export products. Lima o and Venables (2001) haveidentied infrastructure to be an important determinant of transport cost and havenoted that the cost of transporting goods increases with poor infrastructure. Thisphenomenon is observed in case of Bangladesh. The main sea port at Chittagong,lacks modern equipment. The World Bank (2005: 25) has noted that Chittagongs

container terminal can handle 100-5 lifts per berth per day, which is far below theinternational productivity standard of 230 lifts per day. Moreover this port performspoorly because of corruption and inefficient governance which increases the lead

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 611

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

16/23

time and the price of products (Hossain, 2002). The World Bank (2005) hasidentied that bribes paid when importing equipment for the knitted RMG industryraise equipment costs by 6-10%.

Clearly, if these bottlenecks were overcome, the export growth and competitive-ness of Bangladesh RMG could be better.

Disincentives for Investment

Except for the Export Processing Zones, foreign direct investment (FDI) in theRMG industry is highly restricted in Bangladesh. Though this protects localentrepreneurs, the industry suffers in terms of restricted ow of modern technologyand skills. While FDI is restricted, the cost of borrowing from the local bankingsystem is high in Bangladesh compared to its competitors, such as India and China.

The real interest rate in Bangladesh in 2002 was twice that in China and also muchhigher than that in India (Table 10).

The Post-MFA Experience

Before abolition of MFA quotas, a number of studies analysed the possibleconsequences. Most studies predicted a decrease in apparel export from Bangladesh,though the results vary under different assumptions and scenarios (Table 11).Mlachila and Yang (2004) show that results depend on the use of elasticities of substitution between products from different countries (the higher the elasticities, thegreater the impacts).

Looking at the actual export performance of Bangladesh in the USA over the twoyears after the abolition of the MFA import quota (Table 12), it is observed that, ingeneral, exports of previously MFA import quota-restricted RMG products are

Table 10. Real interest rate, selected economies, 2002

Country Interest rate (%)

Bangladesh 12.4India 8.7

China 5.6Sri Lanka 4.5

Source : WDI (2004).

Table 11. Possible consequences of MFA abolition on Bangladesh: comparison of differentstudy ndings, % change from base

Indicators Ahmed (2006)Lips et al.

(2003)Mlachila andYang (2004)

Spinanger (2004)cited in

Razzaque (2005)

Export of apparel7

9.6 to7

15.17

137

6.2 to7

17.7 1.5 to7

7.9GDP 7 0.5 to 7 0.9 Not mentioned 7 0.3 to 7 3.7 7 0.14 to 7 0.54Total exports 7 1.4 to 7 2.4 Not mentioned 7 3 to 7 14.2 2.8 to 7 0.1

612 N. Ahmed

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

17/23

actually growing. RMG export from Bangladesh experienced 19% growth in the USmarket in 2004 and 2005. Contrary to predictions in the studies, both export valueand market share have increased. The market share of Bangladesh in world exportsof apparel was 1.9% in 2003 and rose to 2.3% in 2005 (International TradeStatistics, 2004; 2006). This growth continued in 2006. In 2006, RMG exports to theUS market grew at a rate of 22%. In the US market, it seems that Bangladesh hasactually gained following the abolition of MFA quotas.

However, it is too early to draw rm conclusions about the impacts of MFAimport quota abolition. These impacts can be short term in nature and the medium-to long-term effects will depend on how far Bangladesh exporters can adjust to thechanged competitive trade environment. The most important concern is safe-guarding measures imposed against the leading apparel exporter (China) in the twomost important markets, the EU and the USA. Chinese exports of nine out of thetop ten Bangladesh export products to the US market are facing safeguard measures(Table 13). Therefore, the real competitiveness of Bangladesh exports will berevealed only after the safeguards against Chinese exports are abolished from 2009.

It can be noted that RMG exports to the EU market declined immediately afterthe MFA phase out, from e 3.9 billion in 2004 to e 3.7 billion in 2005 (Razzaque and

Raihan, 2007: 169). One concern for Bangladesh in the post-MFA world is lowutilisation of GSP facilities in the EU market, especially for woven garments. AsBangladeshs woven RMG are known to have low domestic value added contents

Table 12. Performance of Bangladesh RMG products in the US market after MFA abolition,2004-06 (US$ million)

Aggregatedcategories Products 2004 2005 2006 % change(2004-05) % change(2005-06)

0 Total MFA 2065.55 2456.93 2997.94 18.95 22.021 Apparel MFA 1977.56 2371.73 2914.16 19.93 22.872 Non-apparel MF 87.99 85.19 83.78 7 3.18 7 1.6611 Yarns 0.26 0.18 0.02 7 31.66 7 87.0312 Fabrics 3.00 0.95 1.867 7 68.38 96.6714 Made ups/

Miscellaneous84.73 84.07 81.89 7 0.78 7 2.59

30 Cotton product 1303.55 1735.85 2243.42 33.16 29.2431 Cotton apparel 1239.17 1684.55 2185.88 35.94 29.7632 Cot non-apparel 64.38 51.30 57.54 7 20.32 12.1640 Wool products 35.10 27.88 19.51 7 20.56 7 30.0141 Wool apparel 35.08 27.88 19.52 7 20.51 7 30.0142 Wool non-apparel 0.02 0.00 0 7 100.00 7 10060 MMF products 703.54 683.64 721.48 7 2.83 25.5361 MMF apparel 680.21 650.00 695.763 7 4.44 7.0462 MMF non-apparel 23.32 33.65 25.718 44.26 7 23.5680 S and V product 23.36 9.55 13.522 7 59.12 41.6281 S and V apparel 23.10 9.31 13.001 7 59.71 39.7182 S and V non-apparel 0.26 0.24 0.521 7 7.63 114.96

MMF, man-made bres; S and V, silk and vegetable. Though the MFA quota no longer exists, the MFAinformation refers to the products that previously faced quotas.Source : Major Shippers Report (2007).

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 613

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

18/23

they do not meet the ROO requirement in the EU market and thus do not qualify forthe zero duty GSP facility. Razi (2006) has noted that 75% of the woven RMGexports from Bangladesh fail to qualify for the GSP facility. Though 80% of theknitted RMG export to the EU market is successful in utilising GSP facility,domestic value-added contents in woven RMG need to be increased to gain duty-freemarket access to EU markets.

In the post-MFA world, Bangladesh exporters continue with the challengeregarding the situation of workers in RMG factories. The existing situation is suchthat it may affect ongoing attempts to gain duty-free entry in the US market. Oneconcern is the wage received by RMG workers. The minimum wage for workers inBangladesh was introduced in 1994 and there had been no change in this untilOctober 2006. Responding to huge labour unrest, the government announced ahigher minimum wage in textile and apparel industries. The minimum wage for theapparel industry was increased to Tk1662 (US$25 or e 9.65) per month from Tk930in 1994 ( International Herald Tribune , 5 October 2006). Though an increase in theminimum wage indicates an improved situation for workers, this also means higherproduction costs if all other factors remain the same. Thus, the rise in labour cost

should be associated with other cost-reducing measures, such as better power supply,improvements in port facilities, easy access to credit and so on. However, Ahmed(2006: 140 73) has noted that addressing workers rights has the potential to improve

Table 13. Performance of top 20 apparel products of Bangladesh in the USA after MFAimport quota abolition, 2004-06 (US$ million and % change)

Categories Products 2004 2005 2006 % change(2004-05) % change(2005-06)

347 Cotton trouser 177.03 308.58 545.67 74.31 76.83340 Non-knit shirts 266.98 331.70 361.16 24.24 8.88348 W/G slacks, et 118.57 215.93 332.39 82.12 53.93338 Knit shirts 55.26 104.99 179.51 89.99 70.99647 Trousers 97.98 105.73 132.15 7.91 24.99659 Other MMF apparel 122.62 119.37 120.95 7 2.66 1.33352 Cotton underwear 113.61 103.36 115.42 7 9.03 11.67341 W/G non-knit blouse 113.40 116.68 106.80 2.89 7 8.47339 W/G knit blouse 50.51 82.60 105.66 63.54 27.92239 Baby garments 55.48 62.70 90.09 13.03 43.68634 Other coats 89.30 92.65 88.36 3.74 7 4.63359 Other cotton apparel 95.72 84.79 82.20 7 11.42 7 3.05351 Cotton nightwear/pyjamas 30.24 53.77 64.85 77.77 20.61335 W/G cotton coats 40.41 83.88 57.15 107.55 7 31.86640 Non-knit shirts 38.05 49.75 56.48 30.77 13.53334 Other coats 28.88 45.82 53.66 58.64 17.10635 Coats, W/G 59.44 53.23 52.53 7 10.45 7 1.31342 Cotton skirts 34.88 42.86 36.64 22.88 7 14.52648 Slacks, etc. W/G 32.39 32.62 33.89 3.9 0.71646 MMF sweaters 19.96 29.55 33.52 13.4 48.07

MMF, man-made bres; S/V, silk and vegetable; W/G, women and girls. The categories are textile andapparel categories used by the USA.Source : Major Shippers Report (2005).

614 N. Ahmed

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

19/23

workers productivity, which not only increases the income of the workers but alsothe income of the entrepreneurs. Thus, an increase in labour cost will be paid off interms of better return.

In responding to these challenges, the government and the private sector havetaken various steps. In addition to increases in wages, various training programmesfor workers have been conducted. The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers andExporters Association (BGMEA) and Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers andExporters Association have taken initiatives to monitor workers rights in factories,improve factory conditions, locate new markets, improve product quality and thelike. They should also stress highlighting these improvements in the internationalmarkets.

Conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to provide an overview of the drivers of growth in theRMG industry in Bangladesh, while evaluating its potential and challenges. It hasbeen shown that Bangladeshs RMG industry has grown rapidly under the umbrellaof MFA import quotas and with an abundant supply of low-waged workers, butwithout strong domestic backward linkages. Too much product and market con-centration and imported input dependency have raised questions about the future of this industry in an import quota-free regime after the full implementation of theATC. In addition to import quota removal, negative impacts from various regionalPTAs are also of concern for the RMG industry. At the same time, joining a regionalPTA like SAFTA could positively affect the RMG industry and also the economy asa whole. In the US market, the future of top Bangladesh RMG products is uncertainas China is facing a safeguard ban for most of those products. When those bans areremoved, Bangladeshs RMG export to the USA may decline. Duty-free entry in themarket is necessary for future growth or even for sustainability of the RMG industryof Bangladesh.

The issue of removal of safeguard measures against China at the end of 2008 is amajor concern for the RMG industry of Bangladesh. For the government and forthe industry, the hope is that Chinese exports would not be a major problem for afew years beyond 2008. Under WTO rules, selective safeguards may be imposedon any Chinese export causing market disruption until 2013. Moreover, until 2016,non-market economy criteria against China may be used in calculating adumping margin during the process of anti-dumping investigation. However, asthere is no guarantee that these measures will be taken by developed countrymarkets, attempts to improve upon the domestic constraints of the industry shouldreceive the main focus of sustaining and improving competitiveness.

The challenges faced by the RMG industry involve some 10 million people, sosuccess or failure is of great signicance. Any shrinking in the industry will throw alarge number of people out of work. Domestic problems need immediate attention,as competitiveness in an import quota-free world depends on the quick delivery of quality products at a low price. This requires better infrastructure, more investment

and strong backward-linkage industries. Especially important are the improvementsin transport facilities and port facilities and clearance procedure. To ensure timelydelivery setting up a central bonded house could reduce the inventory cost of

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 615

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

20/23

individual rms. The rights of workers have to be addressed and the associatedincrease in production costs can be offset by improvements in productivity.

Notes1 Afsar (2001: 130) has noted that women workers in the RMG industry of Bangladesh mainly come from

poorer backgrounds in terms of their level of education and average landholdings.2 Since 1974, the MFA has been re-negotiated four times and each modication has brought with it

increasingly restrictive measures covering a broader range of products and reducing exibilityprovisions in the system.

3 The major exporters of cotton woven fabrics to Bangladesh in 1996 were Hong Kong, China, India,Pakistan and Taiwan. However, for woven fabrics of synthetic bres, Bangladesh relies on importsmainly from China, Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand, South Korea and Japan (Islam, 2001).

4 However, Razzaque (2005) predicted that Bangladeshs RMG may continue with a better competitiveposition in the EU than in the USA because, in contrast to the USA, which applies high tariffs, the EUapplies no tariffs.

5 Thus, the import of yarn is possible and then the two stages of value-adding are fabrics (knitted orwoven) from yarn and making RMG from the fabrics.

6 Non-members have to reduce pre-tariff prices of their exports to the PTA market and thus the terms of trade (in terms of pre-tariff prices) deteriorate for non-members.

References

Afsar, R. (2001) Sociological Implications of Female Labour Migration in Bangladesh, in R. Sobhanand N. Khundker (eds), Globalisation and Gender: Changing Patterns of Womens Employment inBangladesh , Dhaka: Centre for Policy Dialogue and University Press Limited, pp. 91-165.

Ahmed, N. (2001) Trade Diversion Due to the Europe Agreements: Should Bangladesh Care?, Dhaka:

Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, Research Report, 171.Ahmed, N. (2005) External Sector: Performance and Prospects, Paper presented in the seminar onNational Budget for 2005-06 and PRSP, organised by Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies,Dhaka, 29 May.

Ahmed, N. (2006) Bangladesh Apparel Industry and its Workers in a Changing world Economy, PhDThesis, University of Wageningen, The Netherlands.

Bakht, Z., M. Salimullah, T. Yamagata and M. Yunus (2008) Competitiveness of the Knitwear Industryin Bangladesh: A Study of Industrial Development amid Global Competition, Tokyo: Institute of Developing Economies, IDE Discussion Paper, 169.

Bakht, Z., M. Yunus and M. Salimullah (2002) Machinery Industry in Bangladesh, Tokyo: Institute of Developing Economies Advanced School, IDEAS Machinery Industry Study Report, 4.

Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (2008) http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option com_content&task view&id 12&Itemid 26 (downloaded 23 February 2009).

Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (2008) http://www.bkmea.com/at_a_ glance.php (downloaded 23 February 2009).

Bhattacharya, D. and R. Rahman (2000) Experience with Implementation of WTO-ATC andImplications for Bangladesh, Dhaka: Centre for Policy Dialogue, CPD Occasional Paper Series, 7.

CPD (2001) Policy Brief on Industry and Trade, Dhaka: Centre for Policy Dialogue, CPD Task ForceReport.

Diao, X. and A. Somwaru (2001) Impact of the MFA Phase-Out on the World Economy: AnIntertemporal Global Equilibrium Analysis, Washington DC: International Food Policy ResearchInstitute, TMD Discussion paper, 79.

Economic Review (2007) Bangladesh Economic Review 2007 , Dhaka: Ministry of Finance, Government of Bangladesh.

EPB (2002-03) Bangladesh Export Statistics, 2002-2003 , Dhaka: Export Promotion Bureau of

Bangladesh.EPB (various years) Bangladesh Export Statistics , different issues, Dhaka: Export Promotion Bureau of

Bangladesh.

616 N. Ahmed

http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26http://bgmea.com.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26 -

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

21/23

Gherzi Report (2002) Strategic Development and Marketing Plans for RMG and Related Industries , reportsubmitted by the Gherzi Textile and Project Promotion and Management Associates to the Ministry of Commerce, Government of Bangladesh.

Godfrey, M. (2003) Employment Dimensions of Decent Work: Trade-offs and Complimentarities,Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies, Discussion Paper, 148.

Hertel, T., W. Martin, K. Yanagishima and B. Dimaranan (1996) Liberalizing Manufactures Trade in aChanging World Economy, in W. Martin and L. Winters (eds), The Uruguay Round and the DevelopingCountries , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 183-215.

Hossain, B.M. (2002) Chittagong Port: Potentials, Performance and Private Sector Participation in aGlobalised Situation, Dhaka: BIDS Millennium Series, Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies,Working Paper.

ILO (1999) Report of the Director General on Decent Work, 87th Session, Geneva: International LabourOrganisation.

ILO (2001) World Employment Report , Geneva: International Labour Organisation.International Trade Statistics (2004) Geneva: World Trade Organization.International Trade Statistics (2006) Geneva: World Trade Organization.

Islam, S. (2001) The Textile and Clothing Industry of Bangladesh in a Changing World Economy , Dhaka:Centre for Policy Dialogue and the University Press Limited.

Kabeer, N. and S. Mahmud. (2004) Globalization, Gender and Poverty: Bangladeshi Women Workers inExport & Local Markets, Journal of International Development , 16, pp. 93-109.

Krugman, P. (1991) Geography and Trade , Cambridge: MIT Press.Krugman P. and M. Obsfeld (2000) International Economics, Theory and Policy , Reading: Addison-

Wesley.Lima o, N. and A.J. Venebles (2001) Infrastructure, Geographical Disadvantage, Transport Costs and

Trade, World Bank Economic Review , 15, 3, pp. 451-79.Lips, M., A. Tabeau, F. van Tongeren, N. Ahmed and C. Herok (2003) Textile and Wearing Apparel

Sector Liberalization Consequences for the Bangladesh Economy, Paper presented at the 6thConference on Global Economic Analysis, The Hague.

Major Shippers Report (2005), US Department of Commerce, Office of Textiles and Apparel (16 May).Major Shippers Report (2007) US Department of Commerce, Office of Textile and Apparel(8 February).

Mlachila, M. and Y. Yang (2004) The End of Textile Quotas: A Case Study of the Impact onBangladesh, Washington DC: International Monetary Fund, IMF Working Paper, WP/04/108.

Nordas, H.K. (2004) The Global Textile and Clothing Industry Post the Agreement on Textitles andClothing, Geneva: World Trade Organisation, WTO Discussion Paper.

Quasem, A.S.M. (2002) Backward Linkages in the Textile and Clothing Sector of Bangladesh, Paperpresented at the Executive Forum on National Export Strategies, jointly organised by ITC and SECO,Montreux, Switzerland, 25-8 September.

Quddus, M. and S. Rashid (2000) Entrepreneurs and Economic Development, The Remarkable Story of Garment Export from Bangladesh , Dhaka: The University Press.

Rahman, M. and D. Bhattacharya (2000) Regional Cumulation Facility Under EC-GSP: StrategicResponse from Short and Medium Term Perspectives, Dhaka: Centre for Policy Dialogue, CPDOccasional Paper Series, 9.

Razi, Z. (2006) Future of Clothing Exports from Bangladesh: Disaggregated Scenario, The Daily Star ,2 July.

Razzaque, A. (2005) Sustaining RMG Export Growth after MFA Phase-out: An Analysis of RelevantIssues with Reference to Trade and Human Development, Study conducted for Ministry of Commerce,Government of Bangladesh and United Nations Development Programme, mimeo.

Razzaque, A. and S. Raihan (2007) Two years after MFA Phase Out: Concerns for Bangladesh,in A. Razzaque and S. Raihan (eds), WTO and Regional Trade Negotiation Outcomes: Quantitative

Assessments of Potential Implications on Bangladesh , Dhaka: Unnayan Shamannay and PathakShamabesh, pp. 161-74.

Spinanger, D. (2000) The WTO and Textile and Clothing in a Global Perspective: Whats in it for

Bangladesh? Dhaka: Centre for Policy Dialogue.WDI (2004) World Development Indicators 2004 , Washington: World Bank.World Bank (2005) Bangladesh: Growth and Export Competitiveness , Dhaka: The World Bank.

Sustaining Ready-made Garment Exports from Bangladesh 617

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

22/23

Yang, Y., W. Martin and K. Yanagishima (1997) Evaluating the Benets of Abolishing the MFA in theUruguay Round Package, in T. Hertal (ed.), Global Trade Analysis: Modeling and Applications ,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 271-98.

Zohir, S.C. (2001) Beyond 2004: Strategies for the RMG Sector in Bangladesh, in A. Abdullah (ed.),Bangladesh Economy 2000, Selected Issues , Dhaka: The Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies,pp. 137-63.

618 N. Ahmed

-

8/4/2019 Growth RMG

23/23