Gondar - Phi Kappa Psi

47

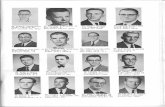

Appendix Theta: The Gondar Intellectual Line Connecting brothers of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University, tracing their fraternal Big Brother/Little Brother line to tri-Founder John Andrew Rea (1869) John Andrew Rea, tri-founder of Phi Kappa Psi at Cornell . . . . . . we begin towards the end of Appendix Gamma: The Halle Intellectual Line . . . . . . . Archbishop Bilson was a descendant of Wilhelm V, Duke of Bavaria . . . . . . Brother Pedro went on mission to Ethiopia, succeeding brother Oviedo . . . . . . Wilhelm Vth founded the University of Ingolstadt, home of the Jesuits . . . . . . Oviedo served God and Susenyos of Ethiopia . . . . . . Ingoldstadt was an intellectual base for Peter Canisus (1549-1552) . . . . . . Susenyos was preceded by Yekuno Amlak of Ethiopia . . . . . . Canisus inspired Francis Xavier and his Conferes . . . . . . and Yekuno came to power with the support of the Ethiopian theologians: Tekle Haymanot, Iyasus Mo'a and the Abbot Yohannes . . . . . . One of Xavier’s conferes was Pedro Paez . . . Below we present short biographies of the Gondor intellectual line of the Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University. “Who defends the House.”

Transcript of Gondar - Phi Kappa Psi

Gondar Appendix Theta: The Gondar Intellectual Line

Connecting brothers of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University, tracing their fraternal Big Brother/Little Brother line

to tri-Founder John Andrew Rea (1869)

. . . we begin towards the end of Appendix Gamma: The Halle Intellectual Line . . .

. . . . Archbishop Bilson was a descendant of Wilhelm V, Duke of Bavaria . . .

. . . Brother Pedro went on mission to Ethiopia, succeeding brother Oviedo . . .

. . . Wilhelm Vth founded the University of Ingolstadt, home of the Jesuits . . .

. . . Oviedo served God and Susenyos of Ethiopia . . .

. . . Ingoldstadt was an intellectual base for

Peter Canisus (1549-1552) . . .

. . . Canisus inspired Francis Xavier and his Conferes . . .

. . . and Yekuno came to power with the support of the Ethiopian theologians: Tekle

Haymanot, Iyasus Mo'a and the Abbot Yohannes . . .

. . . One of Xavier’s conferes was Pedro

Paez . . .

Below we present short biographies of the Gondor intellectual line of

the Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University.

“Who defends the House.”

New York Alpha’s intellectual, Archbishop William Laud, above, was mentored by Bishop Thomas Bilson, below:

Dr. Thomas Bilson the great grandson of Wilhelm V, Duke of Bavaria, a major force in the Catholic Reformation. He descended from a line “bar sinister”, meaning it was illegitimate, but Dr. Bilson was proud of the association, nonetheless. Duke Wilhelm’s liaision produced a daughter, who married Albert Belsson, and the union of this marriage was Hermann Bilson, father of the Bishiop. Bilson was educated in the school of William de Wykeham. He entered New College, at Oxford, and was made a Fellow of his College in 15645. He began to distinguish himself as a poet; but, on receiving ordination, gave himself wholly to theological studies.

New College, Oxford

He was soon made Prebendary of Winchester, and Warden of the College there. In 1596, he was made Bishop of Worcester; and three years later, was translated to the see of Winchester, his native place.

He engaged in most of the polemical contests of his day, as a stiff partizan of the Church of England. When the controversy arose as to the meaning of the so called Apostles’ Creed, in asserting the descent of Christ into hell, Bishop Bilson defended the literal sense, and maintained that Christ went there, not to suffer, but to wrest the keys of hell out of the Devil’s hands. For this doctrine he was severely handled by Henry Jacob, who is often called the father of modern Congregationalism, and also by other Puritans.

Much feeling was excited by the controversy, and Queen Elizabeth, in her ire, commanded her good bishop,

“neither to desert the doctrine, nor let the calling which he bore in the Church of God, be trampled under foot, by such unquiet refusers of truth and authority.”

Dr. Bilsons’ most famous work was entitled “The Perpetual Government of Christ’s Church,” and was published in 1593. It is still regarded as one of the ablest books ever written in behalf of Episcopacy. Dr. Bilson died in 1616, at a good old age, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. It was said of him, that he “carried prelature in his very aspect.” Anthony Wood proclaims him so “complete

in divinity, so well skilled in languages, so read in the Fathers and Schoolmen, so judicious is making use of his readings, that at length he was found to be no longer a soldier, but a commander in chief in the spiritual warfare, especially when he became a bishop!”

Bishop Thomas Bilson was the great grandson of Wilhelm V, “the Pious” von Wittelsbach, Duke of Bavaria:

Wilhelm V, Duke of Bavaria, son of Duke Albrecht V. Born at Munich, 29 September, 1548; died at Schlessheim, 7 February, 1626. He studied in 1563 at the University of Ingolstadt, but left on account of an outbreak of the pest. Nevertheless, he continued his studies elsewhere until 1568, and retained throughout life a keen interest in learning and art. In 1579 he became the reigning duke. He made a reputation by his strong religious opinions and devotion to the Faith, and was called "the Pious". His life was under the direction of the Jesuits. He attended Mass every day, when possible several times a day, devoted four hours daily to prayer, one to contemplation, and all his spare time to devotional reading.

House of Wittelsbach

He received the sacraments weekly, and twice a week in the Advent season and during Lent. Whenever possible he took part in public devotions, processions, and the pilgrimages; thus in 1585 he went on a pilgrimage to Loreto and Rome. His court was jestingly called a monastery, and his capital the German Rome. He founded several Jesuit monasteries, in particular that of St. Michael at Munich, and contributed to the missions in China and Japan.

He did everything possible in Bavaria and the German Empire to further the Catholic Counter-Reformation, and laboured to prevent the spread of Protestantism. Thus it was largely through his efforts that the Archbishopric of Cologne did not become Protestant, due mainly to the vigorous support he gave his brother Ernst, who had been elected archbishop against Gebhard Truchsess.

On the other hand, the manner in which he bestowed benefices upon members of his family makes an unpleasant impression at the present day, though, at that time, this was not considered so unseemly. In the end his brother Ernest had, besides other benefices, five dioceses, and Wilhelm's son Ferdinand was bishop of an equal number; another son intended for the clerical life, Philip, was made Bishop of Ratisbon in 1595 and cardinal in 1596, but died in 1598. Wilhelm had his eldest son Maximilian educated with much care, and in 1597 he resigned the government to Maximilian and led a retired life, devoted to works of piety, asceticism, and charity, and also to the placid enjoyment of his collections of works of art and curiosities.

The house of Wittelsbach in the years before William the Vth reign was allegedly governed by a series of “compacts”. In spite of the decree of 1506 William IV was compelled in 1516, after a violent quarrel, to grant a share in the government to his brother Louis X, an arrangement which lasted until the death of Louis in 1545.

William followed the traditional Wittelsbach policy of opposition to the Habsburgs until in 1534 he made a treaty at Linz with Ferdinand, king of Hungary and Bohemia. This link strengthened in 1546, when the emperor Charles V obtained the help of the duke during the war of the league of Schmalkalden by promising him in certain eventualities the succession to the Bohemian throne, and the electoral dignity enjoyed by the count palatine of the Rhine.

William also did much at a critical period to secure Bavaria for Catholicism. The reformed doctrines had made considerable progress in the duchy when the duke obtained from the pope extensive rights over the bishoprics and monasteries, and took measures to repress the reformers, many of whom were banished; while the Jesuits, whom he invited into the duchy in 1541, made the university of Ingolstadt their headquarters for Germany. William, whose death occurred in March 1550, was succeeded by his son Albert V, who had married a daughter of Ferdinand of Habsburg, afterwards the emperor Ferdinand I. Early in his reign Albert made some concessions to the reformers, who were still strong in Bavaria; but about 1563 he changed his attitude, favoured the decrees of the

Council of Trent, and pressed forward the work of the Counter-Reformation. As education passed by degrees into the hands of the Jesuits the progress of Protestantism was effectually arrested in Bavaria. Albert V patronised art extensively. Artists of all kinds resorted to his court in Munich, and splendid buildings arose in the city; while Italy and elsewhere contributed to the collection of artistic works. The expenses of a magnificent court led the duke to quarrel with the Landschaft (the nobles), to oppress his subjects, and to leave a great burden of debt when he died in October 1579.

The succeeding duke, Albert's son, William Vth (called the Pious), had received a Jesuit education and showed keen attachment to Jesuit tenets. He secured the archbishopric of Cologne for his brother Ernest in 1583, and this dignity remained in the possession of the family for nearly 200 years. In 1597 he abdicated in favour of his son Maximilian I, and retired into a monastery, where he died in 1626.

Wilhelm Vth studied at, and patronized, the University of Ingoldstadt :

The University of Ingolstadt was founded in 1472 by Louis the Rich, the Duke of Bavaria at the time, and its first Chancellor was the Bishop of Eichstätt. It consisted of five faculties: humanities, sciences, theology, law and medicine, all of which were contained in the Hoheschule ('high school'). The university was modeled after the University of Vienna, its chief goal was the propagation of the Christian faith. The university closed in May 1800, by order of the Prince-elector Maximilian IV (later Maximilian I, King of Bavaria). In its first several decades, the university grew rapidly, opening colleges not only for philosophers from the realist and nominalist schools, but also for poor students wishing to study the liberal arts.

University of Ingoldstadt

Among its most famous instructors in the late 1400s were the poet Conrad

Celtes, the Hebrew scholar Johannes Reuchlin, and the Bavarian historian Johannes Thurmair (also known as "Johannes Aventinus").

The Lutheran movement took an early hold in Ingolstadt, but was quickly put to flight by one of the chief figures of the Counter-Reformation: Johann Eck, who made the university a bastion for the traditional Catholic faith in southern Germany. In Eck's wake, many Jesuits were appointed to key positions in the school, and the university, over most of the 1600s, gradually came fully under the control of the Jesuit order. Noted scholars of this period include the theologian Gregory of Valentia, the astronomer Christopher Scheiner (inventor of the helioscope), Johann Baptist Cysat, and the poet Jacob Balde. The Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II received his education at the university.

The 1700s gave rise to the Enlightenment, a movement that was opposed to the church-run universities of which Ingolstadt was a prime example. The Jesuits gradually left the university as it sought to change with the times, until the university finally had become so secular that the greatest influence in Ingolstadt was Adam Weishaupt, founder of the secret society of the Illuminati. On November 25, 1799, the elector Maximilian IV announced that the university's depleted finances had become too great a weight for him to bear: the university would be moved to Landshut as a result. The university finished that year's school term, and left Ingolstadt in May 1800, bringing to a quiet end the school

that had, at its peak, been one of the most influential and powerful institutes of higher learning in Europe.

The University of Ingolstadt (1472-1800), was founded by Louis the Rich, Duke of Bavaria. The privileges of a studium generale with all four faculties had been granted by Pope Pius II, 7 April, 1458, but owing to the unsettled condition of the times, could not be put into effect.

Ingolstadt, modelled on the University of Vienna, had as one of its principal aims the furtherance and spread of Christian belief. For its material equipment, an unusually large endowment was provided out of the holdings of the clergy and the religious orders. The Bishop of Eichstätt, to whom diocese Ingolstadt belongs, was appointed chancellor. The formal inauguration of the university took place on 26 June, 1472, and within the first semester 489 students matriculated. As in other universites prior to the sixteenth century, the faculty of philosophy comprised two sections, the Realists and the Nominalists, each under its own dean.

In 1496 Duke George the Rich, son of Louis, established the Collegium Georgianum for poor students in the faculty of arts, and other foundations for similar purposes were subsequently made. Popes Adrian VI and Clement VII bestowed on the university additional revenues from ecclesiastical property. At the height of the humanistic movement, Ingolstadt counted among its teachers a series of remarkable savatns and writers; Conrad Celtes, the first poet crowned by the German Emperor; his disciple Jacob Locher, surnamed Philomusos; Johann Turmair, known as Aventinus from his birthplace, Abensber, editor of the "Annales Boiorum" and of the Bavarian "Chronica", father of Bavarian history and founder (1507) of the"Sodalitas litteraria Angilostadensis". Johanees Reuchlin, restorer of the Hebrew language and literature, was also for a time at the university.

Although Duke William IV (1508-50) and his chancellor, Leonhard von Eck, did their utmost during thirty years to keep Lutheranism out of Ingolstadt, and though the adherents of the new doctrine were obliged to retract or resign, some of the professors joined the Lutheran movement. Their influence, however, was counteracted by the tireless and successful endeavours of the foremost opponent of the Reformation, Dr. Johann Maier, better known as Eck, from the name of his birth-place, Egg, on the Gunz. He taught and laboured (1510-43) to such good purpose that Ingolstadt, during the Counter-Reformation, did more than any other university for the defence of the Catholic Faith, and was for the church in Southern Germany what Wittenberg was for Protestantism in the north.

In 1549, with the approval of Paul III, Peter Canisus, Salmeron, Claude Lejay, and other Jesuits were appointed to professorships in theology and philosophy. About the same time a college and a boarding school for boys were established, though they were not actually opened until 1556, when the statutes

of the university were revised. In 1568 the profession of faith in accordance with the Council of Trent was required of the rector and professors. In 1688 the teaching in the faculty of philosophy passed entirely in the hands of the Jesuits.

Though the university after this change, in spite of vexations and conflicts regarding exemption from taxes and juridical autonomy, enjoyed a high degree of prosperity, its existence was frequently imperilled during the troubles of the Thirty Years War. But its fame as a home of earning was enhanced by men such as the theologian, Gregory of Valentia; the controversialist, Jacob Gretser (1558-1610); the moralist, Laymann (1603-1609); the mathematician and cartographer, Philip Apian; the astronomer, Christopher Scheiner (1610-1616), who, with the helioscope invented by him, discovered the sun spots and calculated the ime of the sun's rotation; and the poet, Jacob Balde, from Ensisheim in Alsacc, professor of rhetoric. Prominent among the jurists in the seventeenth century were Kaspar Manz and Christopher Berold.

During the latter half of that century, and especially in the eighteenth, the

courses of instruction were improved and adapted to the requirements of the age. After the founding of the Bavarian Academy of Science at Munich in 1759, an anti-ecclesiastical tendency sprang up at Ingolstadt and found an ardent supporter in Joseph Adam, Baron of Ickstatt, whom the elector had placed at the head of the university. Plans, moreover, were set on foot to have the university of the third centenary the Society of Jesus was suppressed, but some of the ex- Jesuits retained their professorships for a while longer.

A movement was inaugurated in 1772 by Adam Weishaupt, professor of

canon law, with a view to securing the triumph of the rationalistic "enlightment" in Church and State by means of the secret society of "Illuminati", which he founded. But this organization was suppressed in 1786 by the Elector Carl Theodore, and Weishaupt was dismissed. On 25 November, 1799, the elector Maximilian IV, later King Maximilian I, decreed that the university, which was involved in financial difficulties, should be transferred to Landshut; and this was done in the following May. Among its leading professors towards the close were Winter the church historian, Schrank the naturalist, and Johann Michael Sailer, writer on moral philosophy and pedagogy, who later became Bishop of Ratisbon.

Oh yeah, Victor “the Doctor” Frankenstein from Mary Shelley's novel

Frankenstein was a fictional student at the University of Ingolstadt.

The University of Ingoldstadt was an intellectual base for Peter Canisus, S.J.:

Blessed Peter Canisius. Born at Nimwegen in the Netherlands, 8 May, 1521; died in Fribourg, 21 November, 1597. His father was the wealthy burgomaster, Jacob Canisius; his mother, Ægidia van Houweningen, died shortly after Peter's birth. In 1536 Peter was sent to Cologne, where he studied arts, civil law, and theology at the university; he spent a part of 1539 at the University of Louvain, and in 1540 received the degree of Master of Arts at Cologne. Nicolaus van Esche was his spiritual adviser, and he was on terms of friendship with such staunch Catholics as Georg of Skodborg (the expelled Archbishop of Lund).

Köln University

Other mentors included Johann Gropper (canon of the cathedral), Eberhard Billick (the Carmelite monk), Justus Lanspergius, and other Carthusian monks. Although his father desired him to marry a wealthy young woman, on 25 February, 1540 he pledged himself to celibacy.

In 1543 he visited Peter Faber and, having made the "Spiritual Exercises" under his direction, was admitted into the Society of Jesus at Mainz, on 8 May. With the help of Leonhard Kessel and others, Canisius, labouring under great difficulties, founded at Cologne the first German house of the order; at the same time he preached in the city and vicinity, and debated and taught in the university.

In 1546 he was admitted to the priesthood, and soon afterwards was sent by the clergy and university to obtain assistance from Emperor Charles V, the nuncio, and the clergy of Liège against the apostate Archbishop, Hermann von Wied, who had attempted to pervert the diocese. In 1547, as the theologian of Cardinal Otto Truchsess von Waldburg, Bishop of Augsburg, he participated in the general ecclesiastical council (which sat first at Trent and then at Bologna), and spoke twice in the congregation of the theologians. After this he spent several months under the direction of Ignatius in Rome. In 1548 he taught rhetoric at Messina, Sicily, preaching in Italian and Latin. At this time Duke William IV of Bavaria requested Paul III to send him some professors from the

Society of Jesus for the University of Ingolstadt; Canisius was among those selected.

On 7 September, 1549, he made his solemn profession as Jesuit at Rome, in the presence of the founder of the order. On his journey northward he received, at Bologna, the degree of doctor of theology. On 13 November, accompanied by Fathers Jaius and Salmeron, he reached Ingolstadt, where he taught theology, catechized, and preached. In 1550 he was elected rector of the university.

In 1552, Peter was sent by Ignatius to the new college in Vienna; there he also taught theology in the university, preached at the Cathedral of St. Stephen, and at the court of Ferdinand I, and was confessor at the hospital and prison. During Lent, 1553 he visited many abandoned parishes in Lower Austria, preaching and administering the sacraments. The king's eldest son (later Maximilian II) had appointed to the office of court preacher, Phauser, a married priest, who preached the Lutheran doctrine. Canisius warned Ferdinand I, verbally and in writing, and opposed Phauser in public disputations. Maximilian was obliged to dismiss Phauser and, on this account, the rest of his life he harboured a grudge against Canisius. Ferdinand three times offered him the Bishopric of Vienna, but he refused. In 1557 Julius III appointed him administrator of the bishopric for one year, but Canisius succeeded in ridding himself of this burden (cf. N. Paulus in "Zeitschrift für katholische Theologie", XXII, 742-8). In 1555 he was present at the Diet of Augsburg with Ferdinand, and in 1555-56 he preached in the cathedral of Prague.

After long negotiations and preparations he was able to open Jesuit colleges at Ingolstadt and Prague. In the same year Ignatius appointed him first provincial superior of Upper Germany (Swabia, Bavaria, Bohemia, Hungary, Lower and Upper Austria). During the winter of 1556-57 he acted as adviser to the King of the Romans at the Diet of Ratisbon and delivered many sermons in the cathedral. By the appointment of the Catholic princes and the order of the pope he took part in the religious discussions at Worms. As champion of the Catholics he repeatedly spoke in opposition to Melanchthon. The fact that the Protestants disagreed among themselves and were obliged to leave the field was due in a great measure to Canisius. He also preached in the cathedral of Worms.

During Advent and Christmas he visited the Bishop of Strasburg at Zabern, started negotiations for the building of a Jesuit college there, preached, explained the catechism to the children, and heard their confessions. He also preached in the cathedral of Strasburg and strengthened the Catholics of Alsace and Freiburg in their faith. Ferdinand, on his way to Frankfort to be proclaimed emperor, met him at Nuremburg and confided his troubles to him. Then Duke Albert V of Bavaria secured his services; at Straubing the pastors and preachers had fled, after having persuaded the people to turn from the Catholic faith. Canisius remained in the town for six weeks, preaching three or four times a day,

and by his gentleness he undid much harm. From Straubing he was called to Rome to be present at the First General Congregation of his order, but before its close Paul IV sent him with the nuncio Mentuati to Poland to the imperial Diet of Pieterkow; at Cracow he addressed the clergy and members of the university.

In the year 1559 he was summoned by the emperor to be present at the Diet of Augsburg. There, at the urgent request of the chapter, he became preacher at the cathedral and held this position until 1566. His manuscripts show the care with which he wrote his sermons. In a series of sermons he treats of the end of man, of the Decalogue, the Mass, the prophecies of Jonas; at the same time he rarely omitted to expound the Gospel of the day; he spoke in keeping with the spirit of the age, explained the justification of man, Christian liberty, the proper way of interpreting the Scriptures, defended the worship of saints, the ceremonies of the Church, religious vows, indulgences. urged obedience to the Church authorities, confession, communion, fasting, and almsgiving; he censured the faults of the clergy, at times perhaps too sharply, as he felt that they were public and that he must avoid demanding reformation from the laity only. Against the influence of evil spirits he recommended the means of defence which had been in use in the Church during the first centuries—lively faith, prayer, ecclesiastical benedictions, and acts of penance. From 1561-62 he preached about two hundred and ten sermons, besides giving retreats and teaching catechism. In the cathedral, his confessional and the altar at which he said Mass were surrounded by crowds, and alms were placed on the altar. The envy of some of the cathedral clergy was aroused, and Canisius and his companions were accused of usurping the parochial rights. The pope and bishop favoured the Jesuits, but the majority of the chapter opposed them. Canisius was obliged to sign an agreement according to which he retained the pulpit but gave up the right of administering the sacraments in the cathedral.

In 1559 he opened a college in Munich; in 1562 he appeared at Trent as papal theologian. The council was discussing the question whether communion should be administered under both forms to those of the laity who asked for it. Lainez, the general of the Society of Jesus, opposed it unconditionally. Canisius held that the cup might be administered to the Bohemians and to some Catholics whose faith was not very firm. After one month he departed from Trent, but he continued to support the work of the Fathers by urging the bishops to appear at the council, by giving expert opinion regarding the Index and other matters, by reports on the state of public opinion, and on newly-published books. In the spring of 1563 he rendered a specially important service to the Church; the emperor had come to Innsbruck (near Trent), and had summoned thither several scholars, including Canisius, as advisers. Some of these men fomented the displeasure of the emperor with the pope and the cardinals who presided over the council. For months Canisius strove to reconcile him with the Curia. He has been blamed unjustly for communicating to his general and to the pope's representatives some of Ferdinand's plans, which otherwise might have ended contrary to the intention of all concerned in the dissolution of the council and in a

new national apostasy. The emperor finally granted all the pope's demands and the council was able to proceed and to end peacefully. All Rome praised Canisius, but soon after he lost favour with Ferdinand and was denounced as disloyal; at this time he also changed his views regarding the giving of the cup to the laity (in which the emperor saw a means of relieving all his difficulties), saying that such a concession would only tend to confuse faithful Catholics and to encourage the disobedience of the recalcitrant.

In 1562 the College of Innsbruck was opened by Canisius, and at that time he acted as confessor to the "Queen" Magdalena (declared Venerable in 1906 by Pius X; daughter of Ferdinand I, who lived with her four sisters at Innsbruck), and as spiritual adviser to her sisters. At their request he sent them a confessor from the society, and, when Magdalena presided over the convent, which she had founded at Hall, he sent her complete directions for attaining Christian perfection. In 1563 he preached at many monasteries in Swabia; in 1564 he sent the first missionaries to Lower Bavaria, and recommended the provincial synod of Salzburg not to allow the cup to the laity, as it had authority to do; his advice, however, was not accepted. In this year Canisius opened a college at Dillingen and assumed, in the name of the order, the administration of the university which had been founded there by Cardinal Truchsess. In 1565 he took part in the Second General Congregation of the order in Rome. While in Rome he visited Philip, son of the Protestant philologist Joachim Camerarius, at that time a prisoner of the Inquisition, and instructed and consoled him.

Pius IV sent him as his secret nuncio to deliver the decrees of the Council of Trent to Germany; the pope also commissioned him to urge their enforcement, to ask the Catholic princes to defend the Church at the coming diet, and to negotiate for the founding of colleges and seminaries. Canisius negotiated more or less successfully with the Electors of Mainz and Trier, with the bishops of Augsburg, Würzburg, Osnabrück, Münster, and Paderborn, with the Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, and with the City and University of Cologne; he also visited Nimwegen, preaching there and at other places; his mission, however, was interrupted by the death of the pope. Pius V desired its continuation, but Canisius requested to be relieved; he said that it aroused suspicions of espionage, of arrogance, and of interference in politics (for a detailed account of his mission see "Stimmen aus Maria-Laach", LXXI, 58, 164, 301).

At the Diet of Augsburg (1566), Canisius and other theologians, by order of the pope, gave their services to the cardinal legate Commendone; with the help of his friends he succeeded, although with great difficulty, in persuading the legate not to issue his protest against the religious peace, and thus prevented a new fratricidal war. The Catholic members of the diet accepted the decrees of the council, the designs of the Protestants were frustrated, and from that time a new and vigorous life began for the Catholics in Germany. In the same year Canisius went to Wiesensteig, where he visited and brought back to the Church the

Lutheran Count of Helfenstein and his entire countship, and where he prepared for death two witches who had been abandoned by the Lutheran preachers.

In 1567 he preached the Lenten sermons in the cathedral of Würzburg, gave instruction in the Franciscan church twice a week to the children and domestics of the town, and discussed the foundling of a Jesuit college at Würzburg with the bishop. Then followed the diocesan synod of Dillingen (at which Canisius was principal adviser of the Bishop of Augsburg), journeys to Würzburg, Mainz, Speyer, and a visit to the Bishop of Strasburg, whom he advised, though unsuccessfully, to take a coadjutor. At Dillingen he received the application of Stanislaus Kostka to enter the Society af Jesus, and sent him with hearty recommendations to the general of the order at Rome. At this time he successfully settled a dispute in the philosophical faculty of the University of Ingolstadt. In 1567 and 1568 he went several times to Innsbruck, where in the name of the general he consulted with the Archduke Ferdinand II and his sisters about the confessors of the archduchesses and about the establishment of a Jesuit house at Hall. In 1569 the general decided to accept the college at Hall.

During Lent of 1568 Canisius preached at Ellwangen, in Würtemberg; from there he went with Cardinal Truchsess to Rome. The Upper German province of the order had elected the provincial as its representative at the meeting of the procurators; this election was illegal, but Canisius was admitted. For months he collected in the libraries of Rome material for a great work which he was preparing. In 1569 he returned to Augsburg and preached Lenten sermons in the Church of St. Mauritius. Having been a provincial for thirteen years (an unusually long time) he was relieved of the office at his own request, and went to Dillingen, where he wrote, catechized, and heard confessions, his respite, however, was short; in 1570 he was obliged again to go to Augsburg. A year latter he was compelled to move to Innsbruck and to accept the office of court preacher to Archduke Ferdinand II.

In 1575 Gregory XIII sent him with papal messages to the archduke and to the Duke of Bavaria. When he arrived in Rome to make his report, the Third General Congregation of the order was assembled and, by special favour, Canisius was invited to be present. From this time he was preacher in the parish church of Innsbruck until the Diet of Ratisbon (1576), which he attended as theologian of the cardinal legate Morone. In the following year he supervised at Ingolstadt the printing of an important work, and induced the students of the university to found a sodality of the Blessed Virgin. During Lent, 1578, he preached at the court of Duke William of Bavaria at Landshut. The nuncio Bonhomini desired to have a college of the society at Fribourg; the order at first refused on account of the lack of men, but the pope intervened and, at the end of 1580, Canisius laid the foundation stone. In 1581 he founded a sodality of the Blessed Virgin among the citizens and, soon afterwards, sodalities for women and students; in 1582 schools were opened, and he preached in the parish church and in other places until 1589.

The canton had not been left uninfluenced by the Protestant movement. Canisius worked indefatigably with the provost Peter Schnewly, the Franciscan Johannes Michel, and others, for the revival of religious sentiments amongst the people; since then Fribourg has remained a stronghold of the Catholic Church. In 1584, while on the way to take part in another meeting of the order at Augsburg, he preached at Lucerne and made a pilgrimage to the miraculous image of the Blessed Virgin at Einsiedeln. According to his own account, it was then that St. Nicholas, the patron saint of Fribourg, made known to him his desire that Canisius should not leave Fribourg again. Many times the superiors of the order planned to transfer him to another house, but the nuncio, the city council, and the citizens themselves opposed the measure; they would not consent to lose this celebrated and saintly man. The last years of his life he devoted to the instruction of converts, to making spiritual addresses to the brothers of the order, to writing and re-editing books. The city authorities ordered his body to be buried before the high altar of the principal church, the Church of St. Nicolaus, from which they were translated in 1625 to that of St. Michael, the church of the Jesuit College.

Canisius held that to defend the Catholic truths with the pen was just as important as to convert the Hindus. At Rome and Trent he strongly urged the appointment at the council, at the papal court, and in other parts of Italy, of able theologians to write in defence of the Catholic faith. He begged Pius V to send yearly subsidies to the Catholic printers of Germany, and to permit German scholars to edit Roman manuscripts; he induced the city council of Fribourg to erect a printing establishment, and he secured special privileges for printers. He also kept in touch with the chief Catholic printers of his time &151; Plantin of Antwerp, Cholin of Cologne, and Mayer of Dillingen &151; and had foreign works of importance reprinted in Germany, for example, the works of Andrada, Fontidonio, and Villalpando in defence of the Council of Trent.

Canisius advised the generals of the order to create a college of authors; urged scholars like Bartholomæus Latomus, Friedrich Staphylus, and Hieronymus Torensis to publish their works; assisted Onofrio Panvinio and the polemic Stanislaus Hosius, reading their manuscripts and correcting proofs; and contributed to the work of his friend Surius on the councils. At his solicitation the "Briefe aus Indien", the first relations of Catholic missioners, were published (Dillingen, 1563-71); "Canisius", wrote the Protestant preacher, Witz, "by this activity gave an impulse which deserves our undivided recognition, indeed which arouses our admiration" ("Petrus Canisius", Vienna, 1897, p. 12).

With apostolic zeal he loved the Society of Jesus; the day of his admission to the order he called his second birthday. Obedience to his superiors was his first rule. As a superior he cared with parental love for the necessities of his subordinates. Shortly before his death he declared that he had never regretted becoming a Jesuit, and recalled the abuses which the opponents of the Church had heaped upon his order and his person. Johann Wigand wrote a vile pamphlet against his "Catechism"; Flacius Illyricus, Johann Gnypheus, and Paul

Scheidlich wrote books against it; Melanchthon declared that he defended errors wilfully; Chemnitz called him a cynic; the satirist Fischart scoffed at him; Andreæ Dathen, Gallus, Hesshusen, Osiander, Platzius, Roding, Vergerio, and others wrote vigorous attacks against him; at Prague the Hussites threw stones into the church where he was saying Mass; at Berne he was derided by a Protestant mob. At Easter, 1568, he was obliged to preach in the Cathedral of Würzburg in order to disprove the rumour that he had become a Protestant. Unembittered by all this, he said, "the more our opponents calumniate us, the more we must love them".

He requested Catholic authors to advocate the truth with modesty and dignity without scoffing or ridicule. The names of Luther and Melanchthon were never mentioned in his "Catechism". His love for the German people is characteristic; he urged the brothers of the order to practise German diligently, and he liked to hear the German national hymns sung. At his desire St. Ignatius decreed that all the members of the order should offer monthly Masses and prayers for the welfare of Germany and the North. Ever the faithful advocate of the Germans at the Holy See, he obtained clemency for them in questions of ecclesiastical censures, and permission to give extraordinary absolutions and to dispense from the law of fasting. He also wished the Index to be modified that German confessors might be authorized to permit the reading of some books, but in his sermons he warned the faithful to abstain from reading such books without permission. While he was rector of the University of Ingolstadt, a resolution was passed forbidding the use of Protestant textbooks and, at his request, the Duke of Bavaria forbade the importation of books opposed to religion and morals. At Cologne he requested the town council to forbid the printing or sale of books hostile to the Faith or immoral, and in the Tyrol had Archduke Ferdinand II suppress such books. He also advised Bishop Urban of Gurk, the court preacher of Ferdinand I, not to read so many Protestant books, but to study instead the Scriptures and the writings of the Fathers. At Nimwegen he searched the libraries of his friends, and burned all heretical books. In the midst of all these cares Canisius remained essentially a man of prayer; he was an ardent advocate of the Rosary and its sodalities. He was also one of the precursors of the modern devotion of the Sacred Heart.

During his lifetime his "Catechism" appeared in more than 200 editions in at least twelve languages. It was one of the works which influenced St. Aloysius Gonzaga to enter the Society of Jesus; it converted, among others, Count Palatine Wolfgang Wilhelm of Neuburg; and as late as the eighteenth century in many places the words "Canisi" and catechism were synonymous. It remained the foundation and pattern for the catechisms printed later. His preaching also had great influence; in 1560 the clergy of the cathedral of Augsburg testified that by his sermons nine hundred persons had been brought back to the Church, and in May, 1562, it was reported the Easter communicants numbered one thousand more than in former years. Canisius induced some of the prominent Fuggers to return to the Church, and converted the leader of the Augsburg Anabaptists.

In 1537 the Catholic clergy had been banished from Augsburg by the city council; but after the preaching of Canisius public processions were held, monasteries gained novices, people crowded to the jubilee indulgence, pilgrimages were revived, and frequent Communion again became the rule. After the elections of 1562 there were eighteen Protestants and twenty-seven Catholics on the city council. He received the approbation of Pius IV by a special Brief in 1561. Great services were rendered by Canisius to the Church through the extension of the Society of Jesus; the difficulties were great: lack of novices, insufficient education of some of the younger members, poverty, plague, animosity of the Protestants, jealousy on the part of fellow-Catholics, the interference of princes and city councils. Notwithstanding all this, Canisius introduced the order into Bavaria, Bohemia, Swabia, the Tyrol, and Hungary, and prepared the way in Alsace, the Palatinate, Hesse, and Poland.

Even opponents admit that to the Jesuits principally is due the credit of saving a large part of Germany from religious innovation. In this work Canisius was the leader. In many respects Canisius was the product of an age which believed in strange miracles, put witches to death, and had recourse to force against the adherents of another faiih; but notwithstanding all this, Johannes Janssen does not hesitate to declare that Canisius was the most prominent and most influential Catholic reformer of the sixteenth century (Geschichte des deutschen Volkes, 15th and 16th editions, IV, p. 406). "Canisius more than any other man", writes A. Chroust, "saved for the Church of Rome the Catholic Germany of today" (Deutsche Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft, new series, II, 106). It has often been declared that Canisius in many ways resembles St. Boniface, and he is therefore called the second Apostle of Germany. The Protestant professor of theology, Paul Drews, says: "It must be admitted that, from the standpoint of Rome, he deserves the title of Apostle of Germany" ("Petrus Canisius", Halle, 1892, p. 103).

Soon after his death reports spread of the miraculous help obtained by invoking his name. His tomb was visited by pilgrims. The Society of Jesus decided to urge his beatification. The ecclesiastical investigations of his virtues and miracles were at first conducted by the Bishops of Fribourg, Dillingen, and Freising (1625-90); the apostolic proceedings began in 1734, but were interrupted by political and religions disorders. Gregory XVI resumed them about 1833; Pius IX on 17 April, 1864, approved of four of the miracles submitted, and on 20 November, 1869, the solemn beatification took place in St. Peter's at Rome. In connection with this, there appeared between 1864-66 more than thirty different biographies. On the occasion of the tercentenarv of his death, Leo XIII issued to the bishops of Austria, Germany, and Switzerland his much-discussed "Epistola Encyclica de memoria sæculari B. Petri Canisii"; the bishops of Switzerland issued a collective pastoral; in numerous places of Europe and in some places in the United States this tercentenary was celebrated and about fifty pamphlets were published.

his brothers, Francis Xavier and his conferes, to revive orthodoxy

beyond the Suez:

University of Paris in 1529, Pierre Favre, Francisco Xavier, and Iñigo de Loyola began sharing a room. They went on to change the world. Early 16th- century Paris was a time of major changes. Influenced by the discovery of the Americas and an ongoing European Renaissance, the culture began embodying the new values of a modern world. Economies were shifting, and a time of scientific innovation was dawning. Stirred by the advent of the printing press, information spread with hitherto unmatched ease. Similar to how the Internet is influencing our times, mass-produced printed materials fueled a new level of literacy, as publications of the Bible, theological concepts, and philosophical musings blew a spirit of inquiry through the Church.

University of Paris “the Sorbonne”

Long before electricity had been discovered and harnessed, the urban

landscape of The emblematic image of University of Paris today—an edifice constructed as part of a rebuilding of the university, launched the same year Loyola and Xavier were canonized.

This was the city into which Iñigo Lopez de Oñaz y Loyola (Ignatius of Loyola) trekked, on fire with a desire to attend the University of Paris and expand his own intellectual and spiritual horizons. He was assigned to a room with two younger men—Pierre Favre (Peter Faber) and Francisco de Isaau de Xavier (Francis Xavier). The friendship of these three college roommates would profoundly affect the times in which they lived and all the centuries since.

Historians usually search for deep causes of developments that reshape the world, but sometimes luck or chance play the major role. Such was the case in 1525 when fate, fortune, or maybe the mysterious working of divine providence assigned Pierre Favre and Francisco Xavier to the same room at the University of Paris, which they shared until 1536. A third roommate, Iñigo de Loyola, joined them for six years (1529-35) until returning to Spain.

From their relationship, the Society of Jesus arose. The blessings that have flowed from this event reach down to our day and affect more than half the nations of our world. St. Francisco Xavier and Blessed Pierre Favre were both born in 1506, so this is the 500th anniversary of their births. St. Ignatius of Loyola died 450 years ago, in 1556. We celebrate all three of these anniversaries in

2006.

In 1534, the three roommates and four friends celebrated Mass in a chapel atop Montmarte. All seven took a vow to work for souls in Jerusalem.

Of peasant origins, Favre worked as a shepherd in the hill country of

Savoy in his youth and was fortunate to receive an excellent education in the cities of Thônes and La Roche, both near his home village of Villaret. His training included Latin, Greek, philosophy, and some theology—a fine combination for success at Europe’s finest university. A degree from Paris would open many doors for a peasant lad. An accomplished student, and almost certainly more learned than his more famous roommates, he helped Loyola grapple with the Greek text of Aristotle. Loyola more than returned the favor.

Favre was a devout student but tortured by scruples till Loyola opened his eyes to see and rejoice in the God of mercy and forgiveness. After returning to Paris from a seven-month visit to Villaret, Favre spent 30 days in 1534 on retreat making the Spiritual Exercises under the direction of Loyola, their originator. Favre was ordained a priest in May of the same year and became a superb director of retreats. St. Peter Canisius made the Spiritual Exercises under Favre’s direction in 1541 and wrote, “Never have I seen nor heard such a learned or profound theologian, nor a man of such shining and exalted virtue.... I can hardly describe how the Spiritual Exercises transformed my soul and senses...I feel changed into a new man.”

Xavier and Favre made an odd pair. Favre was a peasant, pious and studious; Xavier was a Basque nobleman—dark haired, tall, a fine athlete, outgoing. Noblemen of that era seldom took university degrees, but Xavier had few career opportunities in Spain since his family had fought against Charles V during the same French invasion in which Loyola was wounded. This undoubtedly influenced Xavier’s decision to seek an academic career in Paris. While Favre was pious, Xavier was worldly, so Loyola, who wanted to recruit others to serve God, needed a different strategy to win over Xavier. Loyola attended some classes in philosophy taught by Xavier at the College of St. Bauvais and helped pay some of his debts. Several accounts relate that he kept asking Xavier the question of Jesus: “What does it profit a man to gain the whole world and suffer the loss of his soul?”

Gradually Loyola won Favre and Xavier over to his own plan to spend their lives in Jerusalem working for souls. Once won over, Xavier, with his usual enthusiasm, wanted to cancel his three-year commitment to teach at Paris. Loyola and Favre dissuaded him, but as a result he could not devote 30 days to making the Spiritual Exercises until late 1534.

Meanwhile Loyola was winning other gifted students to his Jerusalem plan. On the feast of the Assumption 1534, the three roommates plus four new companions (Diego Laínez, Alfonso Salmerón, Simón Rodrigues, and Nicolás Alonso Bobadilla) climbed up to a chapel atop Montmarte in central Paris. Favre, the only priest among them, celebrated a Mass at which all seven took a vow to work for souls in Jerusalem. From these seven companions sprang the Society of Jesus, the religious order of priests and brothers commonly called the Jesuits. Loyola always regarded the original seven as the Society’s co-founders.

Loyola returned to Spain while the others completed their academic degrees and recruited three more students for the Jerusalem project. They gathered at Venice in 1537, where all but the previously ordained Favre and Salmerón became priests.

Again chance and luck intervened. Bad luck: War between Venice and the Ottoman Empire (which controlled Palestine) broke out. There would be no ship to Palestine. Good luck: The Turks would never have allowed 10 companions to proselytize in Jerusalem. They would have been executed or made into galley slaves, never to be heard from again.

Fortunately, the Montmarte vow had a backup clause: If the companions could not go to Jerusalem, they would put themselves at the pope’s disposal to work for souls. They waited several months, preaching and helping the needy, before they went to Rome and undertook work suggested by Pope Paul III. Favre lectured on scripture at the University of Rome. Loyola directed people through the Spiritual Exercises. Later the pope assigned others of the companions to preaching in various Italian towns. While this arrangement offered opportunities to serve God, it placed their companionship at risk, prompting them to form a religious order whose rules and goals would bind them together, however dispersed their work.

In 1540 they requested and received papal approval for the Society of Jesus. Loyola remained in Rome as superior general of the Jesuits until his death in 1556. The others brought the good news of Christ to the far corners of the world.

Favre helped reform the diocese of Parma in north-central Italy before being sent to the famous Colloquy of Regensburg in Germany, which tried and failed to work out a doctrinal agreement between Lutherans and Catholics. There, Favre gave the Spiritual Exercises to bishops and priests. His next stops

were his native Savoy, then on to Madrid where he spent three months preaching, hearing confessions, and explaining that new order—the Jesuits. He also lectured on the psalms at the University of Cologne, where he gave the Exercises to Peter Canisius, who then entered the Jesuits. Favre’s next assignment was Portugal. Paul III also appointed him a papal theologian at the Council of Trent. He went to Rome where he conversed with Loyola for the first time in seven years. But his health was broken, and he died at age 40 on Aug. 1, 1546, with his old roommate, Loyola, at his bedside.

Xavier’s travels dwarfed those of Favre. King John III of Portugal asked for two Jesuits to serve as missionaries in India. Loyola appointed Rodrigues and Bobadilla, but Bobadilla fell ill. Loyola then asked Xavier, who had been serving in Rome as his secretary, if he would take Bobadilla’s place. Xavier volunteered enthusiastically, left Rome on March 15, 1540, and never saw Loyola or Favre again.

Xavier sailed from Lisbon on a 13-month journey, six of them working in

Mozambique, before arriving at Goa, the main Portuguese base in India.

He set up confraternities to help ex-prostitutes find better lives and

another confraternity to prevent poor young women from falling into prostitution.

At Goa he preached to the Portuguese and tried, not very successfully, to learn the Tamil language. Therefore he required translators during two years of work along the south coast of India where it is believed he baptized more than 10,000 converts. In September 1545 he sailed to Malaysia and spent the next year working in Indonesia. In 1549 he and several other Jesuits sailed to Japan where they converted some 700 Japanese, a people who impressed him as extremely intelligent. He returned to Malaysia and then India in 1551, almost perishing in a typhoon.

Back in India, he reorganized Jesuit work there, then departed for China at a time when foreigners were forbidden to enter. He tried persuading Chinese smugglers to take him ashore, but they considered it too risky. He died on the little island of Sancian near Hong Kong on Dec. 3, 1552, at age 46.

Xavier pioneered and organized Jesuit missionary work in Asia and the Pacific islands. The publication of his letters in Europe attracted many young men to missionary work. Xavier is considered the greatest missionary since St. Paul.

So it was from the Archdiocese of Goa, or Goanensis, that Xavier sailed to evangelize to Asia and his conferes worked to reunited Christian Ethiopia with the West, bridging the divided caused by the expansion of the Ottoman Empire and its allies in the Maghreb. Goa was therefore the Patriarchate of the East

Indies, the chief see of the Portuguese dominions in the East; metropolitan to the province of Goa, which comprised as suffragans the sees of Cochin, Mylapore, and Damão (or Damaun) in India, Macao in China, and Mozambique in East Africa. Mozambique was the gateway to Ethiopia.

The archbishop, who resided at Panjim, or New Goa, had the honorary titles of Primate of the East and (from 1886) Patriarch of the East Indies. He enjoyed the privilege of presiding over all national councils of the East Indies, which were originally be held at Goa (Concordat of 1886 between the Holy See and Portugal, art. 2). The Patronage of the see and of its suffragans belonged to the Crown of Portugal.

The history of the Portuguese conquests in India dates from the arrival of Vasco da Gama in 1498, followed by the acquisition of Cranganore in 1500, Cochin in 1506, Goa in 1510, Chaul in 1512, Calicut in 1513, Damao in 1531, Bombay, Salsette, and Bassein in 1534, Diu in 1535, etc.

From the year 1500, missionaries of the different orders (Franciscans, Dominicans, Jesuits, Augustinians, etc.) flocked out with the conquerors, and began at once to build churches along the coast districts wherever the Portuguese power made itself felt. In 1534 was created an episcopal see suffragan to Funchal in the Madeiras, with a jurisdiction extending potentially over all past and future conquests from the Cape of Good Hope to China. In 1557 it was made an independent archbishopric, and its first suffragan sees were erected at Cochin and Malacca. In 1576 the suffragan was added; and in 1588, that of Funai in Japan. In 1600 another suffragan see was erected at Angamale (transferred to Craganore in 1605) for the sake of the newly-united Thomas Christians; while, in 1606 a sixth suffragan see was established at San Thome, Mylapore, near the modern Madras. In 1612 the prelacy of Mozambique was added, and in 1690 two other sees at Peking and Nanking in China. By the Bulls establishing these sees the right of nomination was conferred in perpetuity on the King of Portugal, under the titles of foundation and endowment.

The limits between the various sees of India were defined by a papal Bull in 1616. The suffragan sees comprised roughly the south of the peninsula and the east coast, as far as Burma inclusive, the rest of India remaining potentially under the jurisdiction of the archdiocese and this potential jurisdiction was the actually exercised even outside Portuguese dominions wherever the Faith was extended by Portuguese missionaries. Missionary work progressed on a large scale and with great success along the western coasts, chiefly at Chaul, Bombay, Salsette, Bassein, Damao, and Diu; and on the eastern coasts at San Thome of Mylapore, and as far as Bengal etc. In the southern districts the Jesuit mission in Madura was the most famous. It extended to the Kistna river, with a number of outlaying stations beyond it. The mission of Cochin, on the Malabar Coast, was also one of the most fruitful. Several missions were also established in the interior northwardds, e.g., that of Agra and Lahore in 1570 and that of Tibet in 1624. Still, even with these efforts, the greater part even of the coast line was

by no means fully worked, and many vast tracts of the interior northwards were practically untouched.

The decline of Portuguese power in the seventheenth century, followed as it was by a decline in the supply of missionaries, etc., soon put limits to the extension of missionary work; and it was sometimes with difficulty that the results actually achieved could be kept up. Consequently, about this time the Holy See began, through the Congregation of Propaganda to send out missionaries independently of Portugal--appointing vicars Apostolic over several districts (The Great Mogul, 1637; Verapoly, 1657; Burma, 1722; Karnatic and Madura, after the suppression of the Jesuits in 1773; Tibet, 1826; Bengal, Madras, and Ceylon, 1834, and others later). In certain places where these vicars Apostolic came into contact with the Portuguese clergy, there arose a conflict of jurisdiction. This was particularly the case in Bombay, which had been ceded to the British in 1661.

The city of Goa, originally a fortress in the hands first of the Hindus and then of the Mohammedans, was taken by the Duke of Albuquerque in 1510. As soon as he became master of the place he built the first church--that of St. Catherine, who thus became the patron of the new city. This was the beginning of a vast series of churches, large and small, numbering over fifty, with convents, hospices and other institutions attached, which made Goa one of the most interesting ecclesiastical cities in the world. The civil splendour was in keeping with the ecclesiastical. But the situation was an unfortunate one. Lying on a low stretch of coast-land, surrounded on two sides by shallow creeks and on the other two by miasmic marshes, the place was soon found unhealthy to such a degree that, after several ravages by epidemics, it was gradually abandoned in favour of Panjim, five miles nearer the sea. The transfer of the Government in 1759 soon led to the total desertion of the old city. In consequence the civil buildings gradually fell into decay or were demolished for the sake of building materials, and, especially after the expulsion of the religious orders in 1835, many churches and monasteries followed suit. In place of houses thick palmgroves gradually grew up, which now, with the exception of a few open spaces, occupy the whole area. The original city extended almost two miles from east to west along the river, and comprised three low hills crowned with religious edifices.

Most of the churches have disappeared, leaving nothing but a cross to mark their site. Others are in various stages of decay, while a few are kept in repair. The finest of those still standing are grouped about the great square: the cathedral (built 1571), in which alone the full liturgy is kept up by a body of resident canons, and adjoining which is an archiepiscopal palace, the Bom Jesus church (Jesuit, built c. 1586), containing the body of St. Francis Xavier incorrupt in a rich shrine; St. Cajetan's, built about 1655, belonging to the Theatines; the Franciscan church of St. Francis of Assisi, built on the site of a mosque 1517-21: and finally the little chapel of St. Catherine, built in 1510. Farther away, on the western hill, stand the great nunnery of St. Monica (1598), still in full repair,

formerly occupied by a large community of native nuns --the only female religious in Goa; the Augustinian church and convent built in 1572, now in ruins; convent and church of St. John of God (1685), now partly in ruins; the Rosary church of the Dominicans, built before 1543; the viceregal chapel of St. Anthony, of about the same date. The last two were still in full repair at the turn of the nineteenth century.

To the south are the ruins of the Jesuit college of St. Paul, built about 1541, and the Carmelite church and convent, built about 1612, occupied after 1707 by Oratorians. The chapel of St. Francis Xavier, the scene of the "Domine, satis est", built before 1542, is still in repair. The following either have entirely disappeared or their sites are marked only by ruins: the chapel of St. Martin, built shortly after 1547; college and church of St. Bonaventure (about 1602); Nossa Senhora de Serra (1513); convent and church of St. Dominic, built about 1548, rebuilt 1550, Santa Luzia at Daujim (about 1544); church of St. Thomas, built to receive the relics of St. Thomas brought from Mylapore in 1560; church of St. Alexis, built before 1600; church of the Holy Trinity, built about the same time; convent and church of Cruz dos Milagres, built after 1619; Nossa Senhora da Luz built before 1543; new college and church of St. Paul (alias convent of St. Roch) used as a college in 1610, church rebuilt later. From the church of Our Lady of the Mount, on the eastern hill, which is still in repair, a magnificent panorama is obtained.

As for Francis Xavier, he was born in the Castle of Xavier near Sanguesa, in Navarre, 7 April, 1506; died on the Island of Sancian near the coast of China, 2 December, 1552. In 1525, having completed a preliminary course of studies in his own country, Francis Xavier went to Paris, where he entered the collège de Sainte-Barbe. Here he met the Savoyard, Pierre Favre, and a warm personal friendship sprang up between them. It was at this same college that St. Ignatius Loyola, who was already planning the foundation of the Society of Jesus, resided for a time as a guest in 1529. He soon won the confidence of the two young men; first Favre and later Xavier offered themselves with him in the formation of the Society. Four others, Lainez, Salmerón, Rodríguez, and Bobadilla, having joined them, the seven made the famous vow of Montmartre, 15 Aug., 1534.

After completing his studies in Paris and filling the post of teacher there for some time, Xavier left the city with his companions 15 November, 1536, and turned his steps to Venice, where he displayed zeal and charity in attending the sick in the hospitals. On 24 June, 1537, he received Holy orders with St. Ignatius. The following year he went to Rome, and after doing apostolic work there for some months, during the spring of 1539 he took part in the conferences which St. Ignatius held with his companions to prepare for the definitive foundation of the Society of Jesus. The order was approved verbally 3 September, and before the written approbation was secured, which was not until a year later, Xavier was appointed, at the earnest solicitation of the John III, King of Portugal, to evangelize the people of the East Indies. He left Rome 16 March, 1540, and

reached Lisbon about June. Here he remained nine months, giving many admirable examples of apostolic zeal.

On 7 April, 1541, he embarked in a sailing vessel for India, and after a tedious and dangerous voyage landed at Goa, 6 May, 1542. The first five months he spent in preaching and ministering to the sick in the hospitals. He would go through the streets ringing a little bell and inviting the children to hear the word of God. When he had gathered a number, he would take them to a certain church and would there explain the catechism to them. About October, 1542, he started for the pearl fisheries of the extreme southern coast of the peninsula, desirous of restoring Christanity which, although introduced years before, had almost disappeared on account of the lack of priests. He devoted almost three years to the work of preaching to the people of Western India, converting many, and reaching in his journeys even the Island of Ceylon. Many were the difficulties and hardships which Xavier had to encounter at this time, sometimes on account of the cruel persecutions which some of the petty kings of the country carried on against the neophytes, and again because the Portuguese soldiers, far from seconding the work of the saint, retarded it by their bad example and vicious habits.

In the spring of 1545 Xavier started for Malacca. He laboured there for the last months of that year, and although he reaped an abundant spiritual harvest, he was not able to root out certain abuses, and was conscious that many sinners had resisted his efforts to bring them back to God. About January, 1546, Xavier left Malacca and went to Molucca Islands, where the Portuguese had some settlements, and for a year and a half he preached the Gospel to the inhabitants of Amboyna, Ternate, Baranura, and other lesser islands which it has been difficult to identify. It is claimed by some that during this expedition he landed on the island of Mindanao, and for this reason St. Francis Xavier has been called the first Apostle of the Philippines. But although this statement is made by some writers of the seventeenth century, and in the Bull of canonization issued in 1623, it is said that he preached the Gospel in Mindanao, up to the present time it has not been proved absolutely that St. Francis Xavier ever landed in the Philippines.

By July, 1547, he was again in Malacca. Here he met a Japanese called Anger (Han-Sir), from whom he obtained much information about Japan. His zeal was at once aroused by the idea of introducing Christanity into Japan, but for the time being the affairs of the Society demanded his presence at goa, whither he went, taking Anger with him. During the six years that Xavier had been working among the infidels, other Jesuit missionaries had arrived at Goa, sent from Europe by St. Ignatius; moreover some who had been born in the country had been received into the Society. In 1548 Xavier sent these missionaries to the principal centres of India, where he had established missions, so that the work might be preserved and continued. He also established a novitiate and house of studies, and having received into the Society Father Cosme de Torres, a spanish priest whom he had met in the Maluccas, he started with him and Brother Juan

Fernández for Japan towards the end of June, 1549. The Japanese Anger, who had been baptized at Goa and given the name of Pablo de Santa Fe, accompanied them.

They landed at the city of Kagoshima in Japan, 15 Aug., 1549. The entire first year was devoted to learning the Japanese language and translating into Japanese, with the help of Pablo de Santa Fe, the principal articles of faith and short treatises which were to be employed in preaching and catechizing. When he was able to express himself, Xavier began preaching and made some converts, but these aroused the ill will of the bonzes, who had him banished from the city. Leaving Kagoshima about August, 1550, he penetrated to the centre of Japan, and preached the Gospel in some of the cities of southern Japan. Towards the end of that year he reached Meaco, then the principal city of Japan, but he was unable to make any headway here because of the dissensions the rending the country. He retraced his steps to the centre of Japan, and during 1551 preached in some important cities, forming the nucleus of several Christian communities, which in time increased with extraordinary rapidity.

After working about two years and a half in Japan he left this mission in charge of Father Cosme de Torres and Brother Juan Fernández, and returned to Goa, arriving there at the beginning of 1552. Here domestic troubles awaited him. Certain disagreements between the superior who had been left in charge of the missions, and the rector of the college, had to be adjusted. This, however, being arranged, Xavier turned his thoughts to China, and began to plan an expedition there. During his stay in Japan he had heard much of the Celestial Empire, and though he probably had not formed a proper estimate of his extent and greatness, he nevertheless understood how wide a field it afforded for the spread of the light of the Gospel. With the help of friends he arranged a commission or embassy the Sovereign of China, obtained from the Viceroy of India the appointment of ambassador, and in April, 1552, he left Goa. At Malacca the party encountered difficulties because the influential Portuguese disapproved of the expedition, but Xavier knew how to overcome this opposition, and in the autumn he arrived in a Portuguese vessel at the small island of Sancian near the coast of China. While planning the best means for reaching the mainland, he was taken ill, and as the movement of the vessel seemed to aggravate his condition, he was removed to the land, where a rude hut had been built to shelter him. In these wretched surroundings he breathed his last.

At the time when Ignatius founded his order Portugal was in her heroic age. Her rulers were full of enterprise, her universities were full of life, her trade routes extended over the then known world. The Jesuits were welcomed with enthusiasm, and made good use of their opportunities. St. Francis Xavier, traversing Portuguese colonies and settlements, proceeded to make his splendid missionary conquests. These were continued by his confreres in such distant lands as Abyssinia, the Congo, South Africa, China, and Japan, by Fathers Nunhes, Silveria, Acosta, Fernandes, and others. At Coimbra, and afterwards at

Evora, the Society made the most surprising progress under such professors as Pedro de Fonseca (d. 1599), Luis Molina (d. 1600), Christovão Gil, Sebastão de Abreu, etc., and from here also comes the first comprehensive series of philosophical and theological textbooks for students. With the advent of Spanish monarchy, 1581, the Portuguese Jesuits suffered no less than the rest of their country. Luis Carvalho joined the Spanish opponents of Father Acquaviva, and when the apostolic collector, Ottavio Accoramboni, launched an interdict against the government of Lisbon, the Jesuits, especially Diego de Arida, became involved in the undignified strife. One the other hand, they played an honorable part in the restoration of Portugal's liberty in 1640, and on its success, the difficulty was to restrain King João IV from giving Father Manuel Fernandes a seat in the Cortes, and employing others in diplomatic missions. Among these Fathers were Antonio Vieira, one of Portugal's most eloquent orators. Up to the Suppression, Portugal and her colonists supported the following missions, of which further notices will be found elsewhere, Goa (originally India), Malabar, Japan, China, Brazil, Maranhao.

It is truly a matter of wonder that one man in the short space of ten years (6 May, 1542 - 2 December, 1552) could have visited so many countries, traversed so many seas, preached the Gospel to so many nations, and converted so many infidels. The incomparable apostolic zeal which animated him, and the stupendous miracles which God wrought through him, explain this marvel, which has no equal elsewhere. The list of the principal miracles may be found in the Bull of canonization. St. Francis Xavier is considered the greatest missionary since the time of the Apostles, and the zeal he displayed, the wonderful miracles he performed, and the great number of souls he brought to the light of true Faith, entitle him to this distinction. He was canonized with St. Ignatius in 1622, although on account of the death of Gregory XV, the Bull of canonization was not published until the following year.

The body of the saint is still enshrined at Goa in the church which formerly belonged to the Society. In 1614 by order of Claudius Acquaviva, General of the Society of Jesus, the right arm was severed at the elbow and conveyed to Rome, where the present altar was erected to receive it in the church of the Gesu.

theological traditions:

Pedro Páez or Pêro Pais (1564 - May 25, 1622) was a Jesuit missionary in Ethiopia. He was the first European who saw and described the source of the Blue Nile. He was born in Olmeda de las Cebollas (now Olmeda de las Fuentes, near Madrid) sixteen years before the union of the Spanish and the Portuguese crowns (1580-1640). He studied at Coimbra. Sent from Goa to Ethiopia as a missionary in 1589, Páez was held captive in Yemen for seven years, from 1590 to 1596, where he used his time to learn Arabic. He finally arrived at Massawa in 1603, and made his way to Fremona, which was the Jesuit base in that land. Unlike his predecessor, Andre de Oviedo, Paul Henze describes him as "gentle, learned, considerate of the feelings of others".

University of Comibra

When summoned to the court of the young negusä nägäst Za Dengel, his knowledge of Amharic and Ge'ez, as well as his knowledge of Ethiopian customs impressed the sovereign so much that Za Dengel decided to convert from the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church to Catholicism -- although Páez warned him not to announce his declaration too quickly. However, when Za Dengel proclaimed changes in the observance of the Sabbath, Páez retired to Fremona, and waited out the ensuing civil war that ended with the emperor's death.

This caution benefited Páez when Susenyos assumed the throne in 1607. Sissinios invited him to his court, where the two became friends. Sissinios made a grant of land to Páez on the peninsula of Gorgora on the north side of Lake Tana, where he built a new center for his fellow Jesuits, starting with a stone church. Paez is believed to be the first European to have discovered the source of the Blue Nile on april 21.st 1618. (Sir Wallis Budge , A history of Ethiopia, p. 397.) Eventually Páez also converted Sissinios to Catholicism shortly before his own death in 1622.

Some of the Catholic churches he designed are still standing, most importantly at Bahir Dar and Gorgora, and were an influence on Ethiopian architecture.

Páez was the first European to visit Lake Tana, one of the sources of the Blue Nile, and to write about tasting coffee. His account of Ethiopia, História da Ethiópia in 1620, has been printed as Volumes II and III of Beccari's Rerum

Aethiopicarum Scriptores occidentales Inedtii (Rome, 1905-17). His work was published in 1945 at Porto in a new edition by Sanceau, Feio and Teixeira, Pêro Pais: História da Etiópia.

In addition to translating the Roman Catechism into Ge'ez, Paez is believed to be the author of the treatise De Abyssinorum erroribus. Páez's writings are one of the few works in Portuguese about Ethiopia that have not been translated into English.

and Emperor Susenyos of Ethiopia . . .

Andrés de Oviedo was born in Illescas, Spain, about 1517, he entered the Society in Rome in 1541. After his studies he was appointed (1545) rector of the Jesuit college at Gandía, and it was he who led Francisco de Borja through his novitiate and received his vows on February 1, 1548. In 1550 Oviedo travelled to Rome with the duke and participated in the discussions on the Constitutions. He became (1551) rector of the new college in Naples and was later assigned to the mission in Ethiopia. He was ordained bishop on May 5, 1555, and became Patriarch of Ethiopia on December 20, 1562. In Ethiopia he lived amid extreme poverty; he died in 1577. The background to brother Oviedo’s mission to Ethiopia lay in the divide occurring as Islam moved west, absorbing early Christian communities along the north coast of Africa into the Caliphate. Ethiopia was cut off from its Christian community.

The Arms of Gandia, Kingdom of Spain

Communication between Rome and Abyssinia became more difficult, and from the end of the eleventh to the beginning of the thirteenth century one could see no bond existing between Abyssinia and the centre of Catholicism. The Sovereign Pontiffs, nevertheless, have bestowed a constant solicitude on the Christians of Ethiopia.

The first missionaries sent to their aid were the Dominicans, whose success, however, roused the fanaticism of the Monophysites against them, and caused their martyrdom. For more than a hundred years silence enfolded the ruins of this Church. At a later period, the fame of the Crusades having spread, pilgrim monks, on their return from Jerusalem, wakened once more, by what they told in the Ethiopian court, the wish to be reunited to the Church.

The Acts of the Council of Florence tell of the embassy sent by the

Emperor Zéra-Jacob with the object of obtaining this result (1452). The union was brought about; but on their home journey, the messengers, while passing through Egypt, were given up to the schismatic Copts, and to the Caliph, and put to death before they could bring the good news to their native land.

In the rural plateaux of northern Ethiopia, one can still find scattered ruins of monumental buildings alien to the country's ancient architectural tradition. This little-known and rarely studied architectural heritage bears silent witness to a fascinating if equivocal cultural encounter that took place in the 16th-17th centuries between Orthodox Ethiopians and Catholic Europeans. The Indigenous and the Foreign explores the enduring impact of the encounter on the religious, political and artistic life of Christian Ethiopia, one not readily acknowledged, not least because the public conversion of the early 17th-century King Susenyos to Catholicism resulted in a bloody civil war enveloped in religious intolerance. Included in this tradition are the surviving architecture of a number of religious and stately buildings of early 17th-century Ethiopia, a period when a mission of Jesuits from Goa, in Western India, was most active at the Ethiopian Christian king's Court. This important heritage, known as pre-Gondarine, is scarcely known outside of Ethiopia.

The Christian kingdom that controlled the Ethiopian high plateaux suffered a series of very deep political, economic, military and religious crises in the period between the late 15th century and the expulsion of the Jesuit missionaries in 1633. The Somali and Afari armies led by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim, called the Gragñ (or “left-handed”) seriously threatened the very existence of the Christian state from 1529 to 1543, when they were finally defeated by the Abyssinians with the help of a small Portuguese expeditionary force sent from Goa, India. Subsequently, parties of Borana and Barentuma Oromo pastoralists began raiding deeper and deeper into Abyssinian territory and, by the end of the 16th century, many had settled in Gojam and Shoa and had become the main adversaries of royal power in Abyssinia.

The Portuguese military collaboration with the Christian Ethiopians served their own strategic interests in their regional rivalry with the Ottoman Turks for control of the trade routes in the Red Sea and the north-western sector of the Indian Ocean. But the Portuguese rulers, together with the Pope in Rome and the head of the Company of Jesus, had the additional intention of establishing a mission in Ethiopia to encourage the population to switch from their Orthodox faith to Catholicism – an intention that made sense in the light of the Counter- Reformation concerns in Southern Europe.