From Renaissance Art to Contemporary Electron Microscopy: DeGroft's Rediscovery of Titian's "Lost"...

Transcript of From Renaissance Art to Contemporary Electron Microscopy: DeGroft's Rediscovery of Titian's "Lost"...

From RenaissanceArt to Contemporary ElectronMicroscopy: DeGroft’s Rediscovery of Titian’s ‘‘Lost’’Portrait of Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, of 1539–40

J. Allan Tucker, MD

Department of Pathology, University of South Alabama,Mobile, Alabama, USA

Aaron H. DeGroft, PhD

Deputy Director and Chief Curator,Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida, USA

At the Ultrapath X meeting in Florence, the regular session openedwith a presentation of Aaron DeGroft’s engrossing story ofinvestigating the authenticity of a portrait of Federico II Gonzaga,Duke of Mantua. In the early 1900s, this work had been deemed to bean authentic production by Titian, a great artist of the ItalianRenaissance. A respected art historian, however, discovered a conflictof dates that led to the conclusion that this work was not authentic. Ina process sometimes analogous to the practice of surgical pathology,Dr. DeGroft pursued a review of the original materials that refutes thisseeming contradiction of dates. Dr. DeGroft also undertook anextensive art historical examination and scientific analysis, includingthe use of electron microscopy, to persuasively conclude that thisportrait is authentic. Further, his work provided a bridge from theconference setting in Florence, rich in Renaissance art, to thecontemporary update on ultrastructural pathology provided by theconference.

Keywords art history, electron microscopy, Renaissance, Titian

Ultrapath X was held in the beautiful and historic cityof Florence, Italy [1]. This city is home to manyoutstanding collections of art, notably Renaissance art.Indeed, one of the scheduled social events was a tourof the Uffizi Gallery. The Uffizi is home to works byartists such as Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raphael,Rembrandt, Rubens, and Titian [2].

In this magnificent city, the participants enjoyed thejuxtaposition of a setting rich in historic art and aconference rich in recent scientific developments. Theopening ceremony and the inaugural lecture of theconferenceöThe Vicissitudinous Role of ElectronMicroscopy in Tumor Diagnosis: A Witness Account,by Dr. Juan Rosaiöwere held in the famous palace inFlorence, the Palazzo Vecchio, built between the 13thand 14th centuries as a seat of the priors of the city [1].Dr. Rosai spoke in the great hall of this structure,the Salone dei Cinquecento, surrounded by paintingsand sculptures by artists such as Michelangelo andVasari [3]. The next day, the regular portion of themeeting began in the Grand Hotel Baglioni. As a seguefrom the backdrop of art in Florence to the scientificsession, the regular meeting began with a presentationof the fascinating work of Aaron DeGroft, whoapplied modern imaging methods, including electron

microscopy, to the study of whether a portrait wasindeed the work of the famous Italian Renaissanceartist Titian.

BACKGROUNDTitian (1477?^1576), known in Italian as Tiziano

Vecellio, is considered the greatest 16th-centuryVenetian painter [4]. This statement, though, fails todefine his full importance as an artist. The Renaissancesaw the development of the linear and sculpturalFlorentine tradition of Michelangelo and Raphael, butTitian provided an alternative approach, epitomized, forexample, by the idealized femininity of Flora (c. 1515,Uffizi) and his impressionistically realized landscapes[4]. This alternative approach was influential for artistssuch as Rubens, Rembrandt, Delacroix, and theimpressionists. Titian’s work, however, is not simplyimportant for its ultimate influence; as noted byRichardson, ``In its own right, moreover, Titian’s workoften obtains the very highest reach of humanachievement in the visual arts’’ [4]. Titian, then, rep-resents one of the key figures in Western art.

During the tour of the Uffizi, the participants at themeeting were able to see several of Titian’s works,including one of his most famous paintings, The Venusof Urbino (c. 1538). The fame of this piece wasenhanced in the United States, in a rather negative way,by Mark Twain. He visited the Uffizi Museum in 1878,and he subsequently described this great piece asfollows: ``there, against the wall, without obstructingrag or leaf, you may look your fill upon the foulest, the

Received 26April 2002; accepted 3 May 2002.

The authors thank Melanie Cox for her expert secretarial assistance andMr. Adrian Hoff for hisexpert photographic assistance.

Address correspondence to J. Allan Tucker, MD, Department of Pathology,2451FillingimSt.,Mobile, AL 36617,USA.E-mail: [email protected]

Ultrastructural Pathology, 26:195±201, 2002

Copyright # 2002 Taylor & Francis

0191-3123/02 $12.00 ‡ .00

DOI:10.1080=01913120290076874

195

Ultr

astr

uct P

atho

l Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rmah

ealth

care

.com

by

Uni

vers

ity o

f N

ewca

stle

Upo

n T

yne

on 1

2/21

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

vilest, the obscenest picture the world possessesöTitian’s Venus’’ [5].

ISSUELike diagnostic pathology, the work of Dr. DeGroft

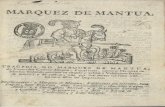

represents a detective story. It centers around a paintingof Federico II Gonzaga, the first Duke of Mantua(Figure 1). In a very detailed and authoritative work onTitian by Crowe and Cavalcaselle in 1877, the authorsnote that the most honorable commission received byTitian in 1540 was to paint the portraits of Federico IIGonzaga (1500^1540) and his wife, MargheritaPaleologa [6]. These items were requested by anindividual named Ottheinrich (1502^1559), CountPalatine of Neuberg and Elector Palatine of the Rhine,i.e., a German prince. Ottheinrich was a distant relativeof Federico II Gonzaga, and, as such, he requested adiplomatic exchange of an array of eclectic items,including antiquities, armor, chewing gum, an ostrich,and portraits. Crowe and Cavalcaselle cited a19th-century Gonzaga archivist who records a letterfrom Federico dated 17 June 1540, agreeing to thisexchange, including the portraits. The painting inquestion (Figure 1) was for years believed to representthat portrait of Federico.

In 1938, in a Gazette des Beaux-Arts article, the greatGerman art historian August Mayer exposed a problemin the story behind this portrait. Citing the samearchivist as Crowe and Cavalcaselle, he noted thatFederico’s letter to Ottheinrich was dated 17 June1540, but that Federico died just 11 days later, on 28June 1540. Mayer’s obvious conclusion, then, was thatthis portrait could not have been Titian’s work. Con-sequently, following 1938, this portrait was neverexhibited and never studied, but instead was stored andconsidered near valueless.

By studying archival documents, performing ascientific analysis, and carrying out an art historicalexamination, Dr. DeGroft has concluded that thisportrait is indeed by Titian. As such, the work has majorsignificance in art history, as Titian’s interaction withFederico was very important in Titian’s artisticdevelopment. Federico introduced Titian to Charles V,resulting in Titian painting Charles V and joining hiscourt in 1548 and 1550, making Titian well-known.Charles V, in turn, introduced Titian to Pope Paul II,who also became the subject of Titian’s work, and itwas through the pope that Titian met Michelangelo inRome.

FIG. 1 The painting in question: is this Titian’sPortrait of Federico II Gonzaga, Duke ofMantua?

FIG. 2 A portion of the letter from Federico toOttheinrich, noting that Titian would painta portrait of Federico …arrowhead†. The date1540 is written by an archivist at the top,though a subsequent archivist changed thedate to 1539 …arrow†.

196 J. A. Tucker and A. H. DeGroft

Ultr

astr

uct P

atho

l Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rmah

ealth

care

.com

by

Uni

vers

ity o

f N

ewca

stle

Upo

n T

yne

on 1

2/21

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

FIG. 3 The closing of Federico’s letter appears to end in ``xxxx,’’ indicating a date of 1540. This date wouldplace the letter only 11 days before Federico’s death, precluding the possibility of a subsequent portrait byTitian.

FIG. 4 On closer inspection of the closing of Federico’s letter, a vertical line can be seen between the lasttwo x’s, indicating a date of 1539, not 1540. This date allows a full year of time for a portrait by Titian.

Art to EM: DeGroft’s Rediscovery of Titian Portrait 197

Ultr

astr

uct P

atho

l Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rmah

ealth

care

.com

by

Uni

vers

ity o

f N

ewca

stle

Upo

n T

yne

on 1

2/21

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTSSometimes a pathologist encounters a surgical

pathology specimen in which the findings run counterto previously reported findings. How does a goodsurgical pathologist proceed? By asking to review theactual slides of the previous material! Dr. DeGroftlaunched a similar approach. He tracked down theoriginal letter from Federico to Ottheinrich in theMantua archives. In that letter, Federico states that hewill have Titian make the portraits so that they will be asauthentic and life-like as possible (Figure 2). At theclosing of the letter, the date appears to end ``xxxx,’’indicating 1540; hence, it was originally archived atthat date, as cited by Crowe and Cavalcaselle(Figure 3). On closer inspection, however, the hand-writing is not clear, and the ink bleeds through(Figure 4). A vertical line appears to be presentbetween the third and fourth ``x,’’ indicating that theactual date was 1539, not 1540, as concluded by theoriginal archivist. In fact, at 2 places in the margin ofthe letter, the notes that give the date as 1540 havebeen crossed out by a subsequent archivist andcorrected to reflect the original inscribed date as 1539,more than a full year before the death of Federico inJune of 1540 and not the mere 11 days recognized byMayer (Figure 2). Dr. DeGroft also discovered a letter

from Federico’s wife to his brother dated 11 October1540, 4 months after Federico’s death, that ref-erences the existence of the portrait. Dr. DeGroft’sinvestigations also revealed additional letters inthe archives in Mantua and in the State Archives inMunich that include many letters between Ottheinrichand Federico. The correspondence begins withthe diplomatic proposal to exchange portraitsof Ottheinrich and his wife with those of Federicoand Margherita. (Ottheinrich also wrote at least oneother Italian Duke requesting such an exchange.)Ottheinrich sent portraits of himself and his wife toFederico, and requested a set of portraits in returnso that they might ``know and recognize one an-other mutually by sight.’’ Also, as state letters, digestsof these letters were maintained in the archives inMunich, and those archives record the letter fromOttheinrich to Federico as occurring on 17 June, 1539,not 1540.

Whether Ottheinrich ever received a portrait is notclear. After Federico’s death, Ottheinrich wrote his heirspolitely requesting the promised items. Federico’s wifeand brother wrote back saying that they could not sendsome items, but did plan to send the portrait. No furtherrecord exists, and the portrait essentially disappearedfor almost 400 years.

FIG. 5 A radiograph of the disputed portrait demonstrates a fine, elaborate diamond-weave canvas of thetype that would be reserved for a major commission.

198 J. A. Tucker and A. H. DeGroft

Ultr

astr

uct P

atho

l Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rmah

ealth

care

.com

by

Uni

vers

ity o

f N

ewca

stle

Upo

n T

yne

on 1

2/21

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

It reappeared in 1911, when it was exhibited inMunich as part of a collection owned by Marczell vonNemes, an art dealer and collector from Budapest. Theexhibit was curated by the director of the museum andart historian Hugo von Tschudi. When von Nemes diedin 1931, his collection was put up for sale, as reportedin The Art News, with this portrait of Federico gracingthe cover of that journal. The von Nemes sale catalogueentries, including the portrait by Titian, were written byAugust Mayer, the German art historian who acceptedthe work as authentic then, but seven years laterconcluded that it was not Titian’s. The portrait sold for90,000 marks, the fourth highest sale behind works byFra Angelico, Rembrandt, and El Greco.

Dr. DeGroft’s research, then, documents thatFederico announced that Titian would paint the portraitin 1539, not 1540, providing ample time to completethe portrait, and that subsequent letters establish theexistence of portrait. The next aspect of his investi-gation centered on whether this disputed painting isindeed that work by Titian.

SCIENTIFIC ANALYSISA scientific analysis of the portrait was begun with a

thorough cleaning. Pigments from the portrait werestudied with the use of scanning electron microscopywith X-ray microanalysis and compared to databases inLondon and Venice. By studying the pigment size andtype and comparing the findings to these databases,this portrait is placed before 1576. Further, the portraitmatches the profile of pigments used by Titian in the1530s. The analysis of this portrait concluded that itwas painted with the same lead white, charcoal, yellowochre, madder, copper resinate, and vermilion that werepopular pigments used by Titian in the 1530s. Titian, attimes, used twice as many pigments and concentratedon the more expensive colors and ignored smalt,indigo, and other cheaper choices that he could haveused. By the end of the 1530s, however, Titianrestricted his palette and, as in this portrait, concen-trated on a more somber array of individual pigments toportray his subjects and more infrequently used thebrighter colors found in some of his earlier works. Theanalysis did not find any of the many pigmentsdeveloped or invented after 1576 that would be presentif painted by a later artist. The particle size of the leadwhite, the vermilion, and the madder was greater thanwould be seen in post-16th-century paintings.

Imaging of the portrait using infrared light and blacklight demonstrated no obscuring restoration or over-painting to major parts of the face and hands.Radiographs of the portrait demonstrated a fine,elaborate diamond-weave canvas (Figure 5); suchwould not be utilized for an ordinary commission butwould be reserved for a major commission. Titianoriginally built up paintings with a series of glazes anddrying varnishes, but after 1540, as his fame grew, hehad more demands on his time, so he worked morequickly, using fewer pigments and skipping layering.The scientific analysis demonstrates that this portrait

represents an intermediate step in these 2 approaches,so that this portrait stands as a major transition inTitian’s technique.

ART HISTORICAL EXAMINATIONTwo earlier portraits of Federico were completed by

Titian. The first, from about 1523, is in the Pradomuseum in Madrid (Figure 6). It entered the collectionin 1799. The style and signature clearly indicated that itwas a Titian, but the subject was unknown for almost100 years. In 1896, it was recognized that this facewas the same as a portrait-bust miniature in theKunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna (Figure 7). Thatminiature includes an inscription naming the sitter. Theface in the miniature is clearly the same face as from thedisputed portrait. Ironically, then, for over 100 years,the sitter in the portrait at the Prado has been identifiedby the fact that the face was the same as the face on aminiature copied from the disputed portrait.

A second known portrait of Federico by Titian wasproduced in 1530 picturing Federico in armor, but onlycopies exist; the original was lost. Other images persistwith Federico’s image, such as Tintoretto’s famousVictory Over Milan, 1521, showing Federico, as well asseveral coins depicting the likeness of Federico. These

FIG. 6 A 1523 portrait of Federico by Titian inthe Prado Museum in Madrid. (Image usedwith permission of Museo National DelPrado.)

Art to EM: DeGroft’s Rediscovery of Titian Portrait 199

Ultr

astr

uct P

atho

l Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rmah

ealth

care

.com

by

Uni

vers

ity o

f N

ewca

stle

Upo

n T

yne

on 1

2/21

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

various images over and over again verify that thesitter in the 3 portraits by Titian is indeed Federico IIGonzaga.

At this point, it is appropriate to return to thehinge-pin miniature of Federico in the ViennaKunsthistoriches Museum. This museum includesnearly 1000 such miniatures depicting lines of heredityfor European aristocracy. The miniatures were paintedfor the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria (1529^1595) forhis castle in Innsbruck, the Schloss Ambras. Ferdinandwanted to document family lines, and, at the time,copying portraits was the only means available toaccurately depict deceased persons in the historiclineages. This collection includes almost 120 miniatureportraits just of the Gonzaga family. (As anotherexample of this same process, one can compare Titian’sportrait of Francesco Maria della Rovere (1536=37) inthe Uffizi with the miniature that copies it.)

The selection of this image to copy for a miniatureindicates that this portrait was a well-respected imageof the Duke. Further, Federico’s son married theArchduke’s sister, and they had a daughter, AnnaCaterina. The Archduke married Anna, his niece andFederico’s granddaughter. This relationship explains

why so many of the miniatures are from the Gonzagafamily. Further, the Archduke agreed to let Federico’sson pick the most truthful portraits for the collection.The likeness of Federico II Gonzaga in the miniature,then, was presumably picked by his son.

The miniature is not the only copy of the disputedportrait. A museum in Mantua includes an early17th-century copy that is inscribed with the name ofthe sitter (Figure 8). Bust-length copies include anengraving published in 1617 and a frieze in the ducalpalace in Mantua painted in the 17th century.

One can compare Titian’s Federico of 1539=40, asseen in a private collection today (Figure 1), withTitian’s Federico of 1523 in the Prado museum(Figure 6). The former portrait used realism, sombercolor, and light to reveal Titian’s first great patron in amanner very characteristic of Titian’s portraits of the

FIG. 7 A portrait-bust miniature of Federico in theKunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna. Notethat the face is clearly a copy of the facefrom the disputed portrait (Figure 1). (Imageused with permission of KunsthistorichesMuseum Wein.)

FIG. 8 A museum in Mantua includes an early17th-century painting inscribed withFederico’s name that obviously represents acopy of the disputed portrait, serving both toconfirm the identity of the sitter and theauthenticity of the work in question. (Imageused with permission of Museo Diocesano diArte Sacra Francesco Gonzaga.)

200 J. A. Tucker and A. H. DeGroft

Ultr

astr

uct P

atho

l Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rmah

ealth

care

.com

by

Uni

vers

ity o

f N

ewca

stle

Upo

n T

yne

on 1

2/21

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

1530s. He holds in his left hand a letter he has justopened, which could be a metaphoric device indicatingthe exchange of letters with Ottheinrich. In his righthand, he holds a half-sheathed stiletto, which he maybe returning to its holder after using it to open the letter.The difference in age is quite apparent. In the earlierpicture, Federico was 23, but he is 39 in the laterpicture. The way he is depicted in both is very similar.Both reveal conservative jewels on the little finger ofeach hand, and he appears to be wearing the sameblack and gold necklace or rosary in both portraits.

CONCLUSIONDr. DeGroft’s remarkable detective work, including

study of archival documents, a scientific analysis of theportrait, and an art historical examination, providepersuasive evidence that the disputed portrait indeedrepresents Titian’s Portrait of Federico II Gonzaga, Dukeof Mantua, of 1539^40. A particularly dramatic aspectof Dr. DeGroft’s work is how the misreading of a single

date by one year could be so pivotal. If Dr. DeGroft’sresearch holds up, and one has every reason to expect itto do just so, it places this disputed portrait alongsideTitian’s other major works. Further, it represents atransition between Titian’s 2 diverse working methodsthat otherwise cannot be seen in any one work.Pragmatically, Dr. DeGroft’s work also elevates thisportrait from almost valueless to a multimillion-dollarjewel.

REFERENCES1. Santucci M, Tucker JA. Ultrapath X: international resurgence of

ultrastructural pathology. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2001;25:1^4.2. Treasures of the Uffizi. New York: Abbeville Press; 1994.3. Cecchi A. Palazzo Vecchio. Florence: Scala; 1989.4. Richardson FL. Titian. In: Microsoft1 Encarta1 Online

Encyclopedia 2001. http:==encarta.msn.com.5. Twain M. A Tramp Abroad (abridged), Neider C, ed. New York:

Harper & Row; 1977:317.6. Crowe JA, Cavalcaselle GB. Titian, His Life and Times, Freedberg

SJ, ed. New York: Garland; 1979.

Art to EM: DeGroft’s Rediscovery of Titian Portrait 201

Ultr

astr

uct P

atho

l Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rmah

ealth

care

.com

by

Uni

vers

ity o

f N

ewca

stle

Upo

n T

yne

on 1

2/21

/14

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.