Final Thesis 8.4

-

Upload

victoria-gartman -

Category

Documents

-

view

121 -

download

0

Transcript of Final Thesis 8.4

Humboldt‐Universität zu Berlin Faculty of Agriculture and Horticulture

Policies and measures for

protected species in wind energy:

An assessment between the U.S. & Germany

Master’s Thesis

A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE:

Victoria Gartman

Major: Arid Land Studies

Supervisory Committee:

Professor Dr. Johann Köppel

Professor Dr. Ulrich Zeller

Dr. Gad Perry

Berlin, April 2014

I

Table of Contents

ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................. 2

ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................................... 1

1. CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1

1.1 Context & Background ........................................................................................................ 1

1.1.1 Policy & Wind Energy ................................................................................................. 1

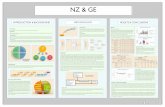

1.1.2 U.S. & Germany in wind energy goals ........................................................................ 4

1.2 Concerns in Wind Energy .................................................................................................... 4

1.3 Best Management Practices: Avoidance & Minimization Measures ................................... 6

1.3.1 Definition ..................................................................................................................... 6

1.3.2 State of Research .......................................................................................................... 8

1.3.3 Research Questions & Hypothesis ............................................................................... 9

1.3.4 Criteria & Conditions ................................................................................................. 10

2. CHAPTER 2: MATERIALS & METHODS ............................................................................. 12

2.1 Study Area .......................................................................................................................... 12

2.1.1 Country Selection ....................................................................................................... 12

2.2 Case Studies ....................................................................................................................... 12

2.2.1 United States .............................................................................................................. 12

2.2.2 Germany ..................................................................................................................... 13

2.3 Literature Research ............................................................................................................ 13

2.4 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 13

3. CHAPTER 3: RESULTS ........................................................................................................... 14

3.1 United States ...................................................................................................................... 14

3.1.1 Laws, Regulations, & Guidelines ............................................................................... 14

3.1.2 U.S. Case Studies ....................................................................................................... 19

3.1.3 Interim Evaluation and Conclusion ............................................................................ 35

3.2 Germany ............................................................................................................................. 38

3.2.1 Laws, Regulations, & Guidelines ............................................................................... 38

3.2.2 German Case Studies ................................................................................................. 44

3.2.3 Interim Evaluation and Conclusion ............................................................................ 55

3.3 Comparative analysis between U.S. & Germany ............................................................... 58

3.3.1 Laws, Regulations, & Guidelines comparison ........................................................... 58

3.3.2 Comparison of Cases .................................................................................................. 60

II

4. CHAPTER 4: DISCUSSION, CONCLUSION ......................................................................... 62

4.1 Discussion .......................................................................................................................... 62

4.1.1 Conclusions ................................................................................................................ 63

4.2 Future Research .................................................................................................................. 64

5. CHAPTER 5: AWKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................... 65

6. CHAPTER 6: LITERATURE CITATIONS .............................................................................. 67

7. CHAPTER 7: APPENDIX ......................................................................................................... 74

TABLE 7.1 U.S. Endangered species allowed to be legally taken at the wind facilities ........... 74

FIGURE 7.2 U.S. geographical map of all nine wind facility locations ................................. 75

TABLE 7.3 Germany species of concern at the wind facilities ................................................. 76

FIGURE 7.4 Germany geographical map of all nine wind facility locations .......................... 81

TABLE 7.5 U.S. avoidance, minimization, & compensatory measures at each of the nine wind

facilities ................................................................................................................................ 82

TABLE 7.6 Germany avoidance, minimization, & compensatory (CEF) measures at each of

the nine wind facilities ................................................................................................................... 83

TABLE 7.7 U.S. and Germany combination of all measures taken at all 18 wind facilities ..... 84

FIGURE 7.9 U.S. EIA and EA Processes with relevant steps highlighted, Source: (U.S. Fish

and Wildlife Service 2012) ............................................................................................................ 85

ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS

ASP Artenschutzprüfung (German endangered species impact assessment)

AWEA American Wind Energy Association

BfN Bundesamt für Naturschutz (Federal Agency for Nature Conservation)

BGEPA Bald & Gold Eagle Protection Act (U.S.)

BLM Bureau of Land Management (U.S.)

BMJV Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz (Federal Ministry

of Justice)

BMP Best Management Practice

BMU/ BMUB Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit

(German Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, & Nuclear Sa-

fety Construction)

BNatSchG Bundesnaturschutzgesetz (Federal Nature Conservation Act)

BO Biological Opinion (U.S.)

BRE Beech Ridge Energy

BWE Bundesverband WindEnergie (German Wind Energy Association)

CCSM Chokecherry & Sierra Madre

CEF Continued ecological function (E.U.)

DOE Department of Energy (U.S.)

DOI Department of the Interior (U.S.)

III

EA Environmental Assessment

EEG Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz (German Renewable Energy Sources Act)

EIAA Environmental Impact Assessment Act (Germany)

EIS Environmental Impact Statement

ESA Endangered Species Act (U.S.)

EU European Union

FCS Favorable conservation status

FEIS Final Environmental Impact Statement

FFH Fauna-Flora-Habitat Directive (The Habitats Directive) (German FFH-

Richtlinie)

FONSI Finding of No Significant Impact

FWS Fish & Wildlife Service (U.S.)

GAO Government Accountability Office

HCP Habitat Conservation Plan (U.S.)

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

ITP Incidental Take Permit

ITS Incidental Take Statement

KF Konzentrationfläche (German, concentration area)

KWP Kaheawa Wind Power

LLC Limited Liability Company (U.S. Corporation)

MBTA Migratory Bird Treaty Act (U.S.)

MW Megawatts

NEPA National Environmental Policy Act

NGO Non-governmental Organization

NRC National Research Council

NWCC National Wind Coordinating Collaborative

NWR National Wildlife Refuge

O&M Operations and Maintenance

PBO Programmatic Biological Opinion

PEIS Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement

ROD Record of Decision (U.S.)

ROW Right of Way (U.S.)

SEA Strategic Environmental Assessment

UBA Umweltbundesamt (German Federal Environmental Protection Agency)

USFWS U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

UVPG Umweltverträglichkeitsprüfung (Environmental Impact Assessment)

WEAP Worker environmental awareness program

WP Windpark (German)

1

ABSTRACT 1

Political frameworks and guidelines concerning endangered species and species of 2

concern affect the development of wind energy in many countries such as the United 3

States and Germany. Renewable energies, with a focus on wind development, are rapid-4

ly growing worldwide and the necessity to ensure environmental and species protection 5

during this development is essential. Concerns in wind energy development include di-6

rect and indirect effects on endangered species or species of concern. Through such pol-7

icies as the Endangered Species Act in the U.S. and the Habitats Directive in Europe, 8

mitigation measures have been taken to lower possible negative impacts on species 9

around wind facilities and wind turbines. 10

This paper shows a multiple-case study analysis of eighteen locations, nine in the 11

U.S. and nine in Germany, with a thorough analysis of literature, political reports, and 12

policies, comparing trans-Atlantic commonalities and differences at or around onshore 13

wind facilities. The biggest differences between U.S. and German policy in terms of 14

species protection is the legal and illegal taking of endangered species, along with 15

avoidance and minimization measures, CEF and compensatory mitigation, and the dif-16

ferent levels of accessibility of information for wind development. With this collection 17

of research, this paper not only aims to show the different mitigation strategies for wild-18

life management around wind facilities, but to also aid policymakers, regulators, and the 19

wind industry in developing the most beneficial cost effective guidelines and/or policies 20

for species protection and wind energy development. 21

22

1. CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 23

1.1 Context & Background 24

1.1.1 Policy & Wind Energy 25

Interest in wind energy and the exploitation of renewable energy sources, arose in 26

the 1970’s after a world-wide oil crisis and a global realization of dependence on fossil 27

fuels. For the last two and a half decades, momentum has picked up with the growing 28

concern about environmental problems and the world’s dwindling non-renewable ener-29

gy sources. Through policies, regulations, and investment, renewable wind energy pro-30

duction has grown exponentially and has led to Germany becoming a leader in the Eu-31

ropean Union and the U.S. being the second highest in installed wind power capacity in 32

2

the world behind China (American Wind Energy Association 2013, Bundersverband 33

WindEnergie 2013). 34

During the past two decades a significant number of countries have created renewa-35

ble energy policy frameworks that have played a major role in the expansion of wind 36

energy. Wind policy in the U.S. has few federal regulations for wind development and 37

operations, leaving mainly states to decide on mandates and regulations, location of 38

wind facilities, and the type of land owners (Geißler, Köppel et al. 2013). For example, 39

California has had a feed-in tariff with aggressive tax incentives since the 1980’s which 40

has spurred other states to do the same in creating state renewable portfolio standards 41

(Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2012) (p.559). These renewable portfolio 42

standards have been used as well as similar feed-in tariffs in European countries since 43

the 1990s. 44

In 1969 the U.S. passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) which was 45

the first policy of its kind in terms of environment and species protection. Fifteen years 46

later the European Union created an Environmental Impact Assessment Directive and 47

five years after in 1990, Germany implemented its own Environmental Impact Assess-48

ment Act (EIAA) (Köppel, Geißler et al. 2012). With the creation of necessary impact 49

assessments (IA) on construction and operation of activities like wind energy develop-50

ment, environmental factors such as species protection became a decision-making factor 51

in primary planning stages. 52

In 2012, Germany produced more than 23, 000 wind turbines with an installed ca-53

pacity of approximately 31,300 MW (megawatts) of clean electricity for businesses and 54

households. 55

3

56

Figure 1: Installed wind power capacity in Germany up to 2012, Source: http://www.wind-57 energie.de/en/infocenter/statistics 58

59

In October 2012, the U.S. Department of the Interior announced it had reached the 60

President’s goal of authorizing 10,000 MW of renewable energy projects on public land. 61

U.S. wind installations in 2012 stood at just over 60,000 MW, the highest installed wind 62

capacity of any other country that year (American Wind Energy Association 2013). 63

64

Figure 2: Total installed wind capacity in the U.S. at the end of 2012, Source: 65 http://awea.rd.net/Resources/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=5059&navItemNumber=742 66

67

Statistics from December 2013 show Germany’s total wind energy capacity reached 68

33,729 MW with only 2,998 MW installed over the year. The U.S. installed 1,084 MW, 69

reaching its capacity of 61,108 MW. With the extension of the Production Tax Credit in 70

2013 in the U.S., 12,000 MW are currently under construction and should be completed 71

4

in 2014 (American Wind Energy Association 2013, Bundersverband WindEnergie 72

2013). 73

1.1.2 U.S. & Germany in wind energy goals 74

After Japan’s Fukushima nuclear incident, Germany passed an “Energiewende” or 75

“Energy Transformation” in 2011 stating the country was closing all nuclear facilities 76

and the nine existing plants by 2022. Their goal has become to hugely expand the use 77

and production of renewables, and in particular, wind power (The Economist 2012). 78

“Energiewende” includes a 55 percent reduction of Greenhouse gases by 2030, achiev-79

ing a 60 percent share of renewable energy targets, giving producers a fixed feed-in tar-80

iff for 20 years guaranteeing a stable income, and having electricity efficiency up by 50 81

percent by 2050. The EU’s binding “20 percent by 2020” target for renewable energy in 82

Member States is a major reason Germany has set such high targets (European 83

Commission 2014). 84

In the U.S., President Obama has given a goal to reach 20 GW from renewable en-85

ergies by 2020 and the Department of Energy hopes to reach its goal of wind energy at 86

20 percent by 2030 (U.S. Department of Energy 2008). Unlike Germany, the U.S. does 87

not have a nationwide federal policy in renewable energy targets or a federal mandate 88

aiming for reductions of Greenhouse gases. The federal government leaves these up to 89

state governments, with many states creating their own mandates and goals in terms of 90

renewable energies. One of the biggest drivers the U.S. government is using for invest-91

ment of renewable energies is the Federal Production Tax Credit combined with state 92

Renewable Portfolio Targets. The NRC Committee estimates by 2020 that the U.S. 93

wind energy development will contribute approximately 4.5 percent electricity genera-94

tion offsetting CO2 emissions (National Research Council 2007). 95

1.2 Concerns in Wind Energy 96

Quite a bit of research has been done about the concerns of endangered species 97

around wind facilities. Katzner (2013) writes; “wind energy is unusual in that it has both 98

direct and indirect effects that are demographically relevant […]. Wind energy devel-99

opment is habitat intensive, as each turbine requires a maintained ground clearing and a 100

service road, as well as installation of electric lines to transport power to the grid” 101

(Katzner, Johnson et al. 2013 p.367). Katzner goes on further to explain that these direct 102

and indirect consequences will affect wildlife populations and community dynamics. 103

Jakle, Drewitt, and the National Research Council (NRC) all discuss similar points that 104

5

turbine characteristics such as size and capacity, siting, abundance of turbines, and hu-105

man activity all determine the risk to wildlife directly through habitat loss and turbine 106

collisions or indirectly though habitat displacement or avoidance (also called barrier 107

effects) (Drewitt and Langston 2006, National Research Council 2007, Jakle 2012). 108

The NRC further details habitat displacement should be considered the biggest con-109

cern rather than direct collision. In Europe, “impacts of wind-energy facilities on habitat 110

are considered to be greater than collision-related fatalities on birds[…]” (National 111

Research Council 2007 p.107-108). It is considered habitat disturbance when bird spe-112

cies such as waterfowl, shorebirds, waders, and passerines avoid the turbines from 75 to 113

800 meters. Additionally, the NRC goes on to say bird displacement associated with 114

wind-energy development has received little attention in the U.S. (National Research 115

Council 2007). 116

Bird vulnerability and mortalities around wind facilities are a combination of site 117

specific, “wind-relief interaction” that is also species specific and can depend on sea-118

sonal factors (Barrios and Rodriguez 2004). Fatalities occurring most at wind facilities 119

are mainly nocturnal, migrating passerines but it has been noted that raptors are most 120

vulnerable. These migrating passerines are in abundance so the higher numbers of colli-121

sions is predicable, but raptors due to their small abundance and higher flight altitudes 122

have become a concern. Migratory tree-roosting bird and bat species also appear to be 123

susceptible to collision (National Research Council 2007 p.7). Birds are known to col-124

lide with a number of manmade structures such as vehicles, buildings and windows, 125

power and communication lines, and wind turbines. Buildings kill 500 million birds 126

annually or 58.2% out of total bird mortalities while wind turbines kill <.01% 127

(Erickson, Johnson et al. 2005). 128

Bat mortality around wind facilities has recently become a worldwide concern and 129

there is some research to see how wind turbines are affecting bats directly and indirect-130

ly. After reported bat fatalities in the thousands in U.S. states like West Virginia and 131

Pennsylvania, research began focusing on mitigation measures such as curtailment1 to 132

minimize these already declining bat populations (Arnett, Huso et al. 2010). With higher 133

bat activity and mortalities coinciding at low wind speeds, the option of curtailment or 134

1 Curtailment can be broadly defined as the consumption of less wind power than is potentially available

at the time. Even though wind is available at a wind facility, the turbines will not run until a certain

threshold of wind speed is met, then the turbines would be turned on to generate electricity.

6

changing the turbine cut-in speed and reducing the operational hours during low wind 135

periods at wind facilities as forms of avoidance and minimization mitigation measures 136

has led to a reductions of bat fatalities by at least 50% without causing major revenue 137

losses (Arnett, Huso et al. 2010, Voigt, Popa-Lisseanu et al. 2012). Yet there are still 138

concerns about the size and form of catchment areas from which these bats originate and 139

biologists such as Voigt feel there needs to be an international agreement to develop and 140

implement bat species conservation and monitoring in the EU (Voigt, Popa-Lisseanu et 141

al. 2012). 142

Besides birds and bats, very little research has been conducted on other species. In 143

terms of mammalian effects from habitat disturbance, the destruction of wooded areas 144

could threaten preferred locations, but overall populations would not be affected by 145

wind-energy development (National Research Council 2007 p.120). Amphibians are 146

often more sensitive to habitat alteration than birds and mammals but no studies around 147

wind-energy developments have been created (as of 2006) (National Research Council 148

2007 p.121). 149

There is a noticeably vast amount of literature and research involving the impacts of 150

wind energy on wildlife as well as other related impacts such as noise pollution, human 151

participation, land development, and visual impacts. The investigation of wind energy 152

impacts on wildlife is in the process of being consolidated through international cooper-153

ation of researchers, agency officials, conservationists, planners, project managers, de-154

velopers, and representatives of the energy industry. Conferences such as the 155

CWW2015 (“Conference on Wind energy and Wildlife impacts 2015”) in Berlin next 156

year are events which are designed to discuss and introduce methods used to properly 157

assess and mitigate impacts. Additionally, they address the adequate planning and per-158

mission processes and policy-making in the wind energy industry, covering cumulative 159

wind energy effects, wind energy in forested areas, and the efficiency of avoidance and 160

mitigation measures (Technische Universität Berlin 2014). 161

1.3 Best Management Practices: Avoidance & Minimization Measures 162

1.3.1 Definition 163

Mitigation is generally defined as (1) avoiding impacts when possible, (2) minimiz-164

ing remaining impacts, and (3) compensating for unavoidable impacts (Jakle 2012). The 165

two main focuses within this paper regarding species protection around wind facilities 166

are mitigation by avoidance and mitigation by reduction/minimization. Mitigation by 167

7

avoidance covers the siting, design, process, technology, alternative routes, and adaptive 168

options to avoid impacts. This form of impact mitigation is often the cheapest and most 169

effective option with the best approaches and the greatest benefit in avoiding impacts 170

early on in the planning stages (Rajvanshi 2008). These minimization measures closely 171

follow avoidance measures, can be grouped together, and are applicable in all phases of 172

a development project. 173

174

Figure 3: Direct (red) and indirect (blue) impacts on wildlife from wind energy, Source: (Drewitt and Langston 175 2006) 176

Best management practices to reduce bird and bat fatalities have been through such 177

measures of avoiding construction and development of wind facilities in environmental-178

ly sensitive areas, using technological and physical changes such as the use of mono-179

poles and burying cable lines, and changing surrounding vegetation types to remove 180

attractiveness for raptors to feed and bats to roost (Baerwald, Edworthy et al. 2009). 181

Mitigation measures can be found detailed in state and federal guidelines and can be 182

observed at wind facilities/sites with HCPs or land development plans. 183

Direct collision/ Mortality

Habitat fragmentation

Altered behavior &

displacement

Decreased fecundity

Decreased breeding success

Acoustic masking

Altered species

competition

8

184

Figure 4: Mitigation Pathway, Source: (Jakle 2012) 185

1.3.2 State of Research 186

Wind energy is known to have direct and indirect impacts on wildlife. The identified 187

direct impacts are habitat displacement and direct collisions with the wind turbines. In-188

directly, wind energy can alter species behavior, decrease fecundity, decrease breeding 189

success, and create barrier effects. The causes of bird fatalities may be attributable to 190

factors such as bird behavior, high prey abundance, turbine design, special arrangement 191

of turbines, and topography (Sterner 2002). However, through appropriate planning and 192

siting, wind facilities can create environmental and social effects which might outweigh 193

some negative impacts on wildlife species and the surrounding environments 194

(Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2012 p.576). These negative impacts can 195

be predicted and mitigated through avoidance and minimization measures in the siting 196

and development phase. These measures are determined through careful planning by the 197

developer, but are guided and enforced through local and regional regulations, state 198

mandates and goals, and federal and/or international acts and policies. 199

There is no in-depth analysis of trans-Atlantic commonalities and differences be-200

tween the procedures and policies set up for protecting endangered species at or around 201

onshore wind facilities. The National Wind Coordinating Collaborative (NWCC) writes: 202

“expanding the amount of research focused on mitigation strategies will not only im-203

prove our knowledge of wildlife management, but it will also help guide policymakers, 204

regulators, industry, and the public in developing guidelines or policies that are benefi-205

cial for wildlife and cost-effective for development,” (National Wind Coordinating 206

Committee 2007 p.84). Few studies have examined the strategies currently in use for 207

reducing the potential impacts of wind power on wildlife species (Government 208

Avoidance

Avoiding siting turbines in sensitive habitats i.e. nesting, foraging, soaring for large birds, locations heavily utilized by migratory birds and bats

Curtailment during sensitive seasons,

feathering, increase cut-in speeds

Minimization Restrict construction around seasonal activities

Minimize lighting to avoid attracting insects and thus, birds & bats

CompensationConstructing bird & bat boxes, protecting or enhancing existing habitat on or away from project site

Funding towards recovery programs , aid, and/or conservation project

Mo

nito

ring

9

Accountability Office 2005). While there have been European studies that cover multi-209

ple EU Member States, no studies have been conducted on the comparison of policies 210

between the U.S. and Germany in terms of species protection and wind energy devel-211

opment. This comparison between the U.S. and Germany can be used in determining 212

better management practices (BMPs) and what policymakers, either nationally, region-213

ally, or locally, can benefit from in knowing the political commonalities and differences 214

and which measures have been particularly beneficial or unsuccessful. 215

1.3.3 Research Questions & Hypothesis 216

Based on what is known about wind energy development and species protection, 217

questions have been posed in areas for further research. The main question of interest in 218

wind energy development is: How do executions of avoidance and minimization mitiga-219

tion measures for species of concern overlap and differ between the United States and 220

Germany? Through thorough review of literature, policy analysis, and case comparison, 221

this main question can be answered. The second question of interest is: How does the 222

U.S.’s habitat conservation plans (HCPs), the E.U.’s continued ecological functions 223

(CEFs), and Germany’s endangered species impact assessment (Artenschutzprüfung, 224

ASP) compare and differs? This question can be answered by a review of literature and 225

policy analysis between Germany’s and the EU’s environmental and species acts with 226

the U.S’s federal policies regarding species protection. The third question is: To what 227

extent can the measures discussed above have the possibility of becoming trans-228

Atlantic? Through a continuation of literature review and case comparison analysis, the 229

aim is to see which adaptations and measures each country can take into consideration 230

with regards to the development of future policies. 231

These questions were chosen to understand whether protection methods in the U.S. 232

and in Germany initiate similar environmental assessments and mitigation approaches. I 233

aim to identify whether policies in both countries use similar practices in terms of 234

avoidance and minimization measures, as well as compensatory and CEF measures for 235

species around wind turbines. Many environmental policies tend to converge at different 236

points in wind energy development and in species protection which will be discussed in 237

a later chapter. 238

Before any work was completed, I formed hypothetical results and what I expected 239

would be conclusive of my compilation of literature review, policy analysis, and case 240

comparison based on the above questions. My main hypothesis is that U.S. policies and 241

10

Germany’s policies will vary in some aspects, yet the comparison will show that their 242

outcomes will be very similar. The U.S. does not have any federal wind energy devel-243

opment regulations, but rather guidelines from federal agencies and NGOs suggesting 244

the best management practices to avoid litigation from such acts as the Migratory Bird 245

Treaty Act, the Bald and Gold Eagle Protection Act, and NEPA. Germany has more 246

regulations and policy requirements from both the EU and its federal laws with some 247

states providing wind facility guidelines but in conclusion, both the U.S. and Germany’s 248

outcomes are very similar. There are a few differences though, such as the U.S.’s inci-249

dental take permit and Germany’s offsite measures. Both countries could benefit in 250

looking at one another’s policies and measures for species protection. Another expected 251

result is that Germany’s continued ecological functions (CEFs) will be similar to some 252

measures within U.S. habitat conservation plans (HCPs) with only slight differences. 253

In addition, the availability of information I was able to access for the U.S. and 254

Germany is important to note and crucial to the understanding of this study. Germany’s 255

lack of transparency included in this research adds difficulty and constraints to public 256

access and my ability to properly analyze cases. The availability of information, such as 257

HCPs and Biological Opinions are easier to access than Germany’s information on pro-258

tected species impact assessments and what CEF measures will be adapted in detail. 259

1.3.4 Criteria & Conditions 260

Criteria and conditions have been created in order to further define my research and 261

explain the boundaries, risks, and issues that have arisen. Within my criteria, I limited 262

my collection of literature and data through online databases from the Texas Tech Uni-263

versity Library to include journals, books, and articles officially published regarding 264

species protection, wind energy development, and a combination of both. I also went to 265

official government websites to collect reports and policies regarding wind facilities and 266

species protection. Such websites include the U.S. Bureau of Land Management 267

(blm.gov), Germany’s BMU (BMU.de), and the European Commission for the Envi-268

ronment (ec.europa.eu/environment). I also collected news articles regarding recent 269

events surrounding wind energy and species protection. Since private land owners do 270

not have to make all information public in regards to development on their lands, the 271

focus lies in wind energy developments on majority federal lands in the U.S. Due to 272

lack of transparency in Germany, I am limited on access to information regarding the 273

11

German cases. Thus, my criteria are broader in case selection and are based on public 274

availability. 275

The focus on research of onshore wind facilities and not offshore facilities is to en-276

sure balance among my cases in the U.S. and Germany. Currently, the U.S. has no oper-277

ational offshore wind energy production unlike Germany, which has 116 offshore wind 278

turbines (Bundersverband WindEnergie 2013). However, there are seven federally 279

funded projects under development off the East and West coasts, the Great Lakes area, 280

and the Gulf of Mexico currently undergoing environmental assessment and planning 281

(three of the seven projects will be selected to complete development and become op-282

erational by 2017) (American Wind Energy Association 2013). Additionally, there are 283

different species of concern, different policies and regulations, and different avoidance 284

and minimization mitigation measures at off-shore wind facilities that would be hard to 285

combine and analyze with onshore wind facilities. 286

In terms of species of concern, I am focusing on federally and internationally endan-287

gered species of birds, mammals, and/or insects. There are many different species of 288

concern, particularly within each country and many factors influence how and why spe-289

cies are protected. Species protection is determined by populations, various regions 290

where particular species nest and breed, migration paths which are used, and particular 291

environment and habitats in which species thrive. In Germany, all birds and bats are 292

protected under European (Habitats and Birds Directives), and federal (BNatSchG) laws 293

(along with a number of other legal foundations for bat and bird conservations not per-294

taining to this paper). In the U.S., the focus will be regarding species which are covered 295

by wind facilities’ Incidental Take Permit (ITP). 296

Regulatory measures heavily influence the development and construction of wind 297

facilities. The measures of research interest cover avoidance and minimization mitiga-298

tion measures with compensatory measures briefly discussed. In the documents found 299

for each case lies a description of which avoidance and minimization measures will 300

work best depending on the site. Avoidance and minimization measures vary slightly in 301

wind facility development for species protection in each country. Compensatory 302

measures can be more difficult to analyze due to the fact that most wind facilities cases 303

selected have neither completed nor thoroughly written up proper measures after the 304

wind site is in operation. 305

12

There are some risks involved in the validity of this research, mainly due to my pre-306

liminary German language skills. I relied on undergraduate translation abstracts and 307

help from fellow colleagues in summarizing my cases and translation websites to help in 308

understanding the information. Additionally, there has been difficulty in finding infor-309

mation as most content is in German. Secondly, in all comparative case analyses there is 310

a certain degree of bias and the selected sample may not reflect the situation as a whole. 311

Lastly, since a majority of the cases have not been completely constructed, not all in-312

formation is available. For example, in Germany not all of the cases have completed an 313

ASP (Artenschutzprüfung) but only baseline surveys with possible CEF measures. In 314

other words, some cases do have concrete measures which will be put into place when 315

wind development sites are constructed, while other cases are still in the planning stag-316

es. 317

318

2. CHAPTER 2: MATERIALS & METHODS 319

2.1 Study Area 320

2.1.1 Country Selection 321

Germany is a top leader in wind energy development in Europe and one of the high-322

est installed-capacity wind energy countries in the world. The U.S. is also one of the 323

highest installed-capacity wind energy countries in the world, second behind China. 324

Both of these nations lead in wind energy development and have strong federal policies 325

for the protection of species. Germany and the U.S. have similar policies and regulations 326

for species of concern but research has not been done comparing the two on this topic 327

with respect to wind energy development. Lastly, both countries have rigorous goals to 328

meet in terms of wind energy and renewable energies in general. It is important that 329

wind facility planning methods are created in detail so as to continue the protection of 330

species while reducing greenhouse emissions. 331

2.2 Case Studies 332

2.2.1 United States 333

I have selected nine cases located throughout the U.S.: Three are located in Califor-334

nia (CA), one in Nevada (NV), one in Wyoming (WY), one in Illinois (IL), one in Ohio 335

(OH), one in West Virginia (WV), and one in Hawaii (HI). Species of concern in these 336

cases are located in Appendix Table 7.1. A geographical map showing the locations of 337

13

these wind facilities are in Appendix Figure 7.2. A description of each case is found in 338

the “Results” chapter with an analysis and comparison of each along with the German 339

cases. 340

2.2.2 Germany 341

I selected nine cases located in Germany within the states of Bayern, Nordrhein-342

Westfalen, and Schleswig-Holstein. Species of concern in these cases are located within 343

Appendix Table 7.3. A geographical map showing the possible locations of these wind 344

turbines are in Appendix Figure 7.4. A description of each case is found in the “Results” 345

section with an analysis and comparison of each along with comparison with the U.S. 346

cases. 347

2.3 Literature Research 348

The research for this thesis is based on a review of relevant laws and regulations 349

within the U.S., the EU’s policies that affect Member States such as Germany, and 350

Germany’s own laws and regulations. The focus is on policy, siting, and permitting 351

documents provided by government agencies such as the U.S.’s BLM, Germany’s 352

BMJV & BMU, and the EU’s EC (European Commission). The research is also based 353

on collection of academic literature regarding species protection, mitigation efforts, and 354

wind energy development. 355

2.4 Methodology 356

The analysis of Germany’s and the U.S.’s procedures of species protection in wind 357

energy development is based mainly on the review of literature on endangered species 358

or species of concern, wind energy development, federal and international policies, and 359

18 wind facility sites. Each case is selected based on the availability of information pro-360

vided for public observation. They consist of possible locations with a specified number 361

of wind turbines for development and written up measures for avoidance and minimiza-362

tion techniques. In the U.S., each case has either a Biological Opinion and/or Habitat 363

Conservation Plan which contains an Incidental Take Statement. The U.S. cases have 364

been approved an Incidental Take Permit (ITP). In Germany, the cases have a possible 365

location for the wind turbines based around a land development plan and consists of 366

either an ASP (Artenschutzprüfung) with CEF (continued ecological function) measures 367

or reviews containing CEF measures with additional avoidance and minimization 368

measures. 369

14

The selected cases in Germany, with the exception of one, pertain to the last three 370

years and in turn some have not been completed. Certain information is unavailable for 371

some of these cases which will be further explained in the “Results” chapter. These new 372

cases are chosen as recent policies within the EU and Germany as they changed and 373

were modified in 2009. The same year, the U.S. modified the Bald and Gold Eagle Pro-374

tection Act to include the taking of potential eagles (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 375

2013 ). The application process for the approval of a wind facility can take up to several 376

years and studies are needed in the potential area for surveying species populations, 377

landscapes, and micro-siting in order to properly follow the new and modified regula-378

tions. 379

Through a comparative case study method I will explain U.S. and EU/Germany situ-380

ations in terms of species protection. Using a multiple-cases approach I will explain 381

commonalities and differences between each case. I will also compare the U.S.’s and 382

Germany’s policies and measures respectively to explain why particular processes are 383

carried out in each country. This explanation-building technique, best explained by Yin, 384

is a case study method which “stipulate[s] a presumed set of causal links about it, or 385

‘how’ or ‘why’ something happened” (Yin 2009). I will further explain the similarities 386

and dissimilarities between the U.S. process of creating HCPs, BOs, and approvals for 387

ITPs and Germany’s use of ASPs and similar documents. In the conclusion of the analy-388

sis I will discuss options and adaptations each country can consider in terms of mitiga-389

tion in wind energy development and how these policies and measures could become 390

trans-Atlantic. 391

392

3. CHAPTER 3: RESULTS 393

3.1 United States 394

3.1.1 Laws, Regulations, & Guidelines 395

The United States became one of the first countries to create federal policies to not 396

only protect different environments from human development but also to protect threat-397

ened or endangered species and their environments. Major acts include the Migratory 398

Bird Treaty Act in 1918 (MBTA), the Bald and Gold Eagle Protection Act in 1940 399

(BGEPA), the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969/1970 (NEPA), and the En-400

dangered Species Act in 1973 (ESA). These policies are, for the majority, overseen by 401

15

the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Land Management in the Depart-402

ment of the Interior. 403

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act prohibits the taking, killing, possession, transporta-404

tion, and importation of over 860 migratory bird species (including their eggs, nests, and 405

parts), unless authorized by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS). The Bald and 406

Gold Eagle Protection Act is similar in that it prohibits the taking and sale of bald and 407

golden eagles (including their eggs, nests, and parts), unless authorized by the USFWS 408

(U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2012). 409

Under these two acts, USFWS regulations broadly define the word “taking” to mean 410

“pursue, hunt, kill, would, trap, capture, or collect” or attempt the taking of these spe-411

cies” (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013). The 412

USFWS does allow permits for scientific collecting, depredation, propagation, and fal-413

conry but there are no provisions for “incidental take” within the MBTA. The USFWS 414

may allow permits for scientific collecting as well under the BGEPA which also in-415

cludes exhibition purposes and religious matters. No permit provisions for “incidental 416

take” under MGEPA were created until 2009, requiring project developers to create an 417

Eagle Conservation plan detailing avoidance and minimization measures to protect bald 418

and golden eagles if the developer were to request eagle takes. 419

The U.S. environmental review process at both state and federal levels have been in 420

effect for over 40 years while the European Union’s environmental processes are just 421

over 25 years (Köppel, Geißler et al. 2012). The National Environmental Policy Act 422

(NEPA) is a federal law stating that developers who wish to carry out any action on fed-423

eral lands with significant environmental consequences must submit an environmental 424

impact statement (EIS) or environmental assessment (EA). For example, if a wind de-425

velopment project is sited on federal lands or is going to connect to a federal transmis-426

sion line, the developer must create and, through the NEPA EA/EIS process, identify 427

potential measures to mitigate identified impacts (Jakle 2012). Two flow charts of the 428

EA and EIA process can be found in Appendix Figure 7.9. 429

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) passed in 1973 is to “provide a means whereby 430

the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be 431

conserved, to provide a program for the conservation of such endangered species and 432

threatened species, and to take such steps as may be appropriate to achieve the purposes 433

16

of [certain] treaties and conventions[…]” (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013). Sec-434

tions 7, 9, 10 are most important regarding the taking of protected species and the coop-435

eration of federal agencies to ensure survival of these species on federal lands. Section 436

7(a)(2) requires the USFWS to “consider one-time and cumulative effects of federal 437

agency actions on threatened and endangered species and their habitats, and authorizes 438

the imposition of requirements to minimize the impacts of authorized takes” (U.S. Fish 439

and Wildlife Service 2013). It provides that, if a Biological Opinion (BO) issued by the 440

FWS determines that the proposed federal agency action complies with Section 7(a)(2) 441

jeopardy and critical habitat standards, the USFWS will issue an incidental take state-442

ment to the appropriate agency. Section 9 of the ESA details take violation regulations, 443

specifically Sec. 9(a)(2) stating “it is unlawful for any person subject to the jurisdiction 444

of the United States to take any such species within the US or the territorial sea of the 445

United States [and] violate any regulation pertaining to such species or to any threated 446

species of fish or wildlife” (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013). Section 9’s take 447

standard, unlike Section 7(a)(2)’s jeopardy standard, considers injuries to an individual 448

member of a listed species and only to listed wildlife species while Section 7(a)(2) ap-449

plies to all listed species and plants. In addition, Section 9 applies to any habitat of listed 450

wildlife species unlike the Section 7(a)(2) critical habitat standard which is only desig-451

nated to the critical habitats of listed species (Department of the Interior Wind Turbine 452

Guidelines Advisory Committee 2008). 453

Lastly, Section 10 of the ESA authorizes the taking of threatened or endangered spe-454

cies if a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) is developed and will minimize and mitigate 455

impacts of the taking. Section 10 authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to issue an ITP 456

from the FWS Endangered Species program, which will result in the taking of a listed 457

wildlife species by a non-federal landowner engaged in an otherwise unlawful activity 458

covered by the HCP. In order for wind developers to apply for an ITP, the application 459

must accompany an HCP to show that the effects of the approved ITP are minimized 460

and mitigated (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2012). An HCP is a tool used to resolve 461

endangered species conflicts in allowing some loss of endangered species in exchange 462

for compensatory activities which minimize and mitigate for the loss (Bonnie 1999). 463

17

464

For proposed projects such as the construction of a wind facility, both the Bureau of 465

Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) must follow 466

the ESA requirements to ensure that any action they authorize or fund will not jeopard-467

ize endangered or threatened species or destroy their designated critical habitat (U.S. 468

Fish and Wildlife Service 2012). One objective of an EIS is to evaluate potential im-469

pacts resulting from the issuance of an Incidental Take Permit (ITP) supported by a 470

Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013). The purpose of 471

the HCP process associated with this permit is to guarantee that there will be adequate 472

minimization and mitigation of the effects for the authorized incidental take. Developers 473

with an authorized ITP are allowed to continue activities, such as constructing and oper-474

ating a wind facility. In order to obtain an ITP, the developer must complete the permit 475

application with the components of a standard application, a HCP with an incidental 476

take statement, and a drafted NEPA EIS or EA. While the permit is processing, the 477

USFWS will prepare the ITP, write a Biological Opinion (BO) under section 7 of the 478

ESA, and finalize the NEPA analysis documents. For 60 days, there will also be a public 479

comment process during this application process and are considered in the permit deci-480

sion (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2012, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013). Since 481

Migratory Bird Treaty Act

(MBTA) [1918]

Prohibits the taking, killing, possession, transportation, &

importation of 860+ migratory birds, their

eggs, parts, nests (except authorized by

FWS)

Authorizes some activities (i.e.

scientific collection, depredation, propagation,

falconry)

NO PERMIT PROVISIONS FOR

“INCIDENTAL TAKE”

Bald & Gold Eagle

Protection Act (BGEPA) [1940]

Prohibits the taking and sale of bald &

gold eagles and their nests, parts, nests

(except authorized by FWS)

Authorizes permits for scientific or

exhibition purposes, religious purposes for

Indian tribes.

NO PERMIT PROVISIONS FOR “INCIDENTAL TAK

Endangered Species Act (ESA) [1973]

Protects 1,265+ species at risk for extinction,

(threatened / endangered); prohibits the taking of protected

animal species, incl. actions that “harm” or

“harass”; federal actions may not jeopardize listed

species or adversely modify critical habitats

Authorizes permits for the “taking” of

protected species for scientific purposes, est.

experimental populations, or is incidental to an

otherwise legal activity

Figure 5: Federal Wildlife Protection Laws, Source: (Government Accountability Office 2005)

18

the HCP is done by the developer, the USWFS and BLM have created guidelines to help 482

in creating these documents and, if followed correctly, to help avoid litigation in the 483

future. In terms of wind development on a federal policy level, there are no acts or poli-484

cies in which the U.S. is only playing a minimal role in approving wind power facilities. 485

The government can regulate wind facilities that are only on federal lands or have some 486

form of federal involvement such as receiving funds (Government Accountability Office 487

2005 p.31). Most of these regulations vary from state to state and in local agencies, with 488

the regulation of wind power facilities on nonfederal land largely the responsibility of 489

state and local governments. For instance, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) 490

states in its Federal Land Policy & Management Act (Sec. 103(c)) that public lands are 491

to be managed for multiple uses that take into account the long-term needs of future 492

generations for renewable and non-renewable resources (Bureau of Land Management 493

2001). In terms of wind development on federal lands, the BLM discourages any siting 494

on or near “Areas of Critical Environmental Concern,” including Wilderness Study Are-495

as, Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Historic and Scenic Trails (Jakle 2012). 496

However, there are U.S. federal agencies and organizations that have created guide-497

lines to help in wind energy development and species protection. In 2003, the USFWS 498

created voluntary “Land-Based Guidelines in Wind Energy” that focus on avoidance, 499

minimization, and monitoring for all commercial wind energy projects (Jakle 2012, U.S. 500

Fish and Wildlife Service 2012). These official guidelines help developers create wind 501

facilities that fall within acceptable measures for species protection. Included in the 502

FWS Guidelines is a Habitat Conservation Plan Handbook Addendum, or the “Five 503

Point Policy,” which provides techniques and guidance in biological goals and objec-504

tives, adaptive management, monitoring, permit duration, and public participation (U.S. 505

Fish and Wildlife Service 2013). 506

Other directives include the “Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement in 507

Wind Energy Development on BLM Lands in the Western U.S.” Published in 2005, this 508

PEIS provides analysis of mitigation measures, including consideration of avoidance 509

and minimization measures (Bureau of Land Management 2005) . The National Wind 510

Coordinating Council (NWCC) in 2007 created a “Toolbox” compiling mitigation poli-511

cies, guidelines, and research for direct and indirect impacts on wildlife caused by wind 512

power facilities (National Wind Coordinating Committee 2007). Other wind facility 513

guidelines such as the Federal Aviation Chapter 13, Marking and Lighting (2007), De-514

19

partment of the Interior (DOI) Wind Turbine Guidelines Advisory Committee Memo-515

randum (2008), and the U.S. Forest Service Final Directives (2011) are recommenda-516

tions helpful in wind power development but are not crucial to this study (Department of 517

the Interior Wind Turbine Guidelines Advisory Committee 2008, U.S. Fish and Wildlife 518

Service 2013). 519

3.1.2 U.S. Case Studies 520

The following nine cases are the Alta East Wind Energy Project, the Beech Ridge 521

Wind Energy Project, the Buckeye Wind Power Project, the Chokecherry & Sierra Ma-522

dre Wind Energy Project, the Kaheawa Pastures Wind Energy Generation Facility, the 523

Monarch Warren County Wind Turbine Project, the Ocotillo Express Wind Project, the 524

Searchlight Wind Energy Project, and the Tule Wind Project. Four of the nine have al-525

ready been constructed or are currently under construction. The five others are still in 526

the planning process but will be soon constructed and aim for operation in 2014. Focus 527

lies on the wind project’s HCPs, BOs, ITPs, and in one case, the Record of Decision for 528

descriptions and information pertaining to this research. At each site there is an examin-529

ing the logistics, the species which are allowed to be legally taken and the dealings with-530

in the ITP, avoidance and minimization measures, and, in some cases, what compensa-531

tory measures are discussed. While some plant species are protected under the ESA, I 532

will only cover birds, mammals and bats, reptiles and amphibians, and in one case, in-533

sects. Appendix Table 7.1 shows which species is allowed to be legally taken and how 534

many at each wind facility. 535

Alta East Wind Energy Project: The Alta East Project is about 3 miles (4.8 km) 536

away from the town of Mojave and was approved for construction on May 24, 2013 537

located in Kern County, California. The project footprint would encompass 59 acres (23 538

ha) of public land within the 1,999 acre (808 ha) BLM right-of-way. A Right-of-Way 539

(ROW) is the formal authorization from the BLM for public lands to be used for pro-540

jects, such as wind facilities, roads, and transmission lines, for a specific amount of 541

time. Alta Windpower Development, LLC has been allowed to construct 51 turbines, 542

with 42 turbines on BLM lands and 9 on surrounding private lands. Total installed wind 543

capacity for the project maximum would be 153 MW. The BLM has approved all as-544

pects of the project, including the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS), Rec-545

ord of Decision (ROD), and ROW for the 30-year life of the project. Included in the 546

Final Environmental Impact Assessment (FEIS) are the USFWS’s BO and ITP which 547

20

incorporates all mitigation measures to be taken and the Incidental Take Statement (ITS) 548

(Bureau of Land Management 2013). A Habitat Conservation Plan was not created be-549

cause the USFWS considered the FEIS and ROD covered all mitigation measures need-550

ed for the ITP. 551

The Alta East Wind Energy Project is the first wind project to authorize for the “tak-552

ing” of the federally endangered California condor (Gymnogyps califorianus). 399 Cali-553

fornia condors compromised the total world population as of February 28,2013 and are 554

continuing to breed successfully with the help of captive breeding programs and reintro-555

duction of condors in the early 1990s (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Field Supervisor 556

of Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office 2013). While lead poisoning is the main cause of 557

death for this species, collision risk is a large concern as these birds have not evolved to 558

look directly ahead while flying. The Alta East Wind Energy Project is not located with-559

in and will not affect the critical habitat of the California condor (they have not been 560

documented within 12 miles of the project site recently or historically). However, with 561

its growing population and large home range, this could be a concern in the future. 562

The incidental take of a condor is authorized within the BO which includes 563

measures to avoid, reduce, and offset potential adverse effects on the California condor. 564

In accordance with the FEIS, Alta Windpower, LLC is to create a number of detailed 565

plans, protective measures, and surveying measures to avoid litigation. In addition to the 566

California condor, the Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) is federally endangered and 567

the Alta East wind facility has thus created measures to ensure potential adverse effects 568

are reduced and avoided. 569

General protective measures include siting turbines away or immediately adjacent 570

to the upwind sides of ridge crests, burying cable lines, and regular monitoring of 571

above-ground cables, and wires. Measures taken for the California condor include im-572

plementing a Condor Monitoring Avoidance Plan in which a VHF-detection system will 573

be installed to scan a 16 mile perimeter of the project and send alerts to qualified biolo-574

gists who will be fully employed at the wind facility. The Condor Monitoring Avoid-575

ance Plan will be in effect 30 minutes prior to sunrise and 30 minutes after sunset, dur-576

ing which the fulltime biologists will be observing the whole project site. Hazardous 577

waste, microtrash, and carcasses which may attract condors to the wind facility, will be 578

immediately cleared. The developer and BLM have also created in-depth protocols 579

should a condor be seen, as well as adaptive management strategies, but these will not 580

21

need to be discussed in this paper. If a California condor is struck by a turbine blade, the 581

project will be immediately confined to nighttime-only operations in which the USFWS 582

and BLM will re-initiate formal consultation for future measures. 583

Even though federally protected, the desert tortoise does not have an ITP as the wind 584

facility will not likely jeopardize the continued existence of this species. However, 585

measures are still taken to minimize impacts of the wind facility such as the presence of 586

an authorized biologist onsite as well as biological monitors to survey and clear them 587

from harm’s way (i.e. under parked vehicles, burrowed under turbines, and inside 588

pipes). One concern of the desert tortoise is the abundance of invasive weeds across its 589

range. Measures like limiting human access can help minimize those impacts to increase 590

tortoise population. Since there is heavy sheep grazing, unauthorized off-road vehicle 591

use, and trash dumbing in the vicinity, the desert tortoise has low numbers within the 592

project site, and thus relatively few will live within this highly active area. 593

During construction, the facility will create a worker environmental awareness pro-594

gram (WEAP) which will be given to all employees within the project. The project de-595

scribes different protocols for environmental awareness safety and steps to be taken if or 596

when a condor or desert tortoise is seen. A 15 mph speed limit will be in effect through-597

out the construction and operations period and temporary fencing will be built to ex-598

clude desert tortoises from construction areas. 599

Overall, the ITS estimates that one California condor is likely to be killed at this fa-600

cility and the extent of take resulting from the construction of this wind facility will be a 601

subset of the number of desert tortoises and eggs estimated within the project site. After 602

the review of avoidance and minimization measures and an adaptive management out-603

line, the ITP has allowed this facility to take one California condor. As a compensatory 604

measure, Alta Windpower LLC, will contribute $100,000 to the California Condor Re-605

covery and to outreach educational programs (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Field 606

Supervisor of Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office 2013). 607

Beech Ridge Wind Energy Project: The Beech Ridge Wind Energy Project is locat-608

ed in Greenbrier and Nicholas Counties, West Virginia (WV) and is broken down into 609

two phases. Beech Ridge Energy LLC originally planned 124 wind turbines to be in 610

operation by the end of 2010, the first phase with 67 wind turbines, and the second 611

phase with 57 wind turbines. However, in 2009, a lawsuit was filed against them alleg-612

22

ing that the project had violated section 9 of the Endangered Species Act, for its poten-613

tial in the taking of the federally endangered Indiana Bat (Myotis sodalis) and its failure 614

to properly apply for an ITP. After a detailed settlement agreement, the second phase of 615

the Beech Ridge Wind Energy Project would contain a HCP with an ITP covering both 616

phase I and II and cutting out 24 of the original 124 turbines built on the site. Addition-617

ally, phase I has to follow a strict turbine operation timetable with specified times of day 618

and seasons during which bats are not flying and monthly and annual reports on any 619

taking of the Indiana bat has to be submitted (Beech Ridge Energy LLC 2013). 620

Beech Ridge Energy (BRE) fulfilled those obligations and on December 5, 2013 621

was approved for phase II for the construction of 33 wind turbines. The project is locat-622

ed on 63,000 acre (25,495 ha) tract in West Virginia (BRE leased 27,000 acres [10,926 623

ha] of this tract) and will total 100 wind turbines with an installed capacity of 186 MW 624

(Beech Ridge Energy LLC 2013, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Field Supervisor of 625

West Virginia Field Office 2013). Beech Ridge Wind Energy Project’s HCP gives de-626

tailed information on the project and its covered activities, including measures taken for 627

avoidance and minimization mitigation for the Indiana Bat and Virginia Big-eared Bat 628

(Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus). 629

The Indiana Bat lives primarily in the Eastern and Midwest U.S. states. During win-630

ters, the Indiana bat hibernates in only a few cave-like locations (i.e. abandoned mines, 631

railroad tunnels) known as hibernacula and roost in forested areas or fragmented forests 632

in the summer. There are only 88 known Indiana bat hibernacula (37 in West Virginia) 633

which are considered Critical Habitat and cannot be destroyed or disturbed. The 634

USFWS has created a recovery plan to protect these areas and to help monitor popula-635

tion trends. There are no known detections of Indiana bats in the surrounding Beech 636

Ridge site during the summer breeding season and no roost trees have been identified, 637

however the possibility of roosts could occur in the future. A Priority One hibernacu-638

lum, Hellhole, is located approximately 75 miles away from the Beech Ridge Wind En-639

ergy facility and houses both the Indiana Bat and Virginia big-eared bat (Beech Ridge 640

Energy LLC 2013). 641

The Virginia big-eared bat has five caves that are listed as Critical Habitat by the 642

USFWS, all of which are in West Virginia. The species has seen only a slight increase 643

in population in the last 27 years of monitoring. Similar to the Indiana Bat, there are no 644

23

detections of this species at or around Beech Ridge and there have been no reported col-645

lisions at any wind facility of either species (Beech Ridge Energy LLC 2013). 646

While there have been no reports of these species in pre-surveying and monitoring at 647

Beech Ridge, both bat species are included in the HCP and BO. The project is on the 648

edges of the species’ range and there may be potential for these species to either pass 649

through this area or hibernate in one of the surrounding unoccupied caves in the future. 650

Thus, mitigation measures will be implemented to avoid the taking of these species. 651

Conservation measures include reducing the number of turbines from 124 to 100, mov-652

ing the proposed phase II expansion area away from known caves, and working with 653

federal agencies in micro-siting turbine locations to minimize impacts. Tree clearing 654

will be limited when bats are in hibernation, a 25 mph speed limit to be enacted, and 655

lastly, testing and implementing a turbine operation curtailment plan. This curtailment 656

plan specifies feathering all turbines at less than 2rpm below the 4.8 m/s cut-in speed 657

beginning at sunset for a period of five hours from July 15 through October 15, during 658

which the largest peak in bat mortality occurs (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Field 659

Supervisor of West Virginia Field Office 2013). In terms of compensatory measures, the 660

BRE will complete off-site projects, proposing to fund specific off-site conservation 661

projects which meet USFWS criteria in order to receive an ITP. 662

The incidental take statement within the BO, after review of the HCP, allows BRE 663

to take up to 14 Virginia big-eared bats and up to 53 Indiana Bats over the course of the 664

25-year project. The incidental take is either from collision of the blades or from ba-665

rotrauma during project operations but will not affect the population of either species of 666

bat over the course of time (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Field Supervisor of West 667

Virginia Field Office 2013). 668

Buckeye Wind Power Project: On July 18, 2013, the USFWS approved the Buckeye 669

Wind Power Project’s HCP and issued an ITP to Buckeye Wind LLC. The construction 670

of 100 wind turbines with a maximum capacity of 250 MW is taking place in Cham-671

pagne County, Ohio (OH) and has been issued the legal taking of 130 Indiana Bats. Un-672

der the Incidental Take Statement, “no more than 26 Indiana bats may be taken over any 673

consecutive 5-year period, starting in any one year in which take of more than 5.2 Indi-674

ana bats is estimated to have occurred” (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ohio Ecological 675

Services Field Office 2012). Additionally, no more than 14.2 Indiana bats may be taken 676

in any 1 year. Buckeye Wind Power Project is situated within 80,051 acres (32,395 ha) 677

24

with a permanent footprint of 129.8 acres (52.5 ha) (Buckeye Wind LLC 2013). Pre-678

construction surveys showed that Indiana bats fly through the project area during sum-679

mer maternity season for migration, so extra steps have been taken to avoid adverse ef-680

fects on this species. Other species of concern are the Rayed bean mussel (Villosa faba-681

lis), which is federally endangered, and the Eastern massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus 682

catenatus catenatus), which is a federal candidate species. While mitigation measures 683

will be taken to avoid the taking of these species, they are not listed in the ITP, as their 684

environmental preferences and suitable habitat are not located within the project area. 685

Steps taken to avoid and minimize impacts to Indiana bats as well as the Rayed bean 686

mussel and Eastern massasauga rattlesnake are detailed in the HCP and in the BO. 687

Avoidance measures include the movement of the project site upon discovery of Indiana 688

bats in the area, siting turbines so that none will be closer than 1.8 miles (2.9 km) away 689

from known maternity roost trees, and situating the turbines to avoid disrupting large 690

stretches of contiguous forest habitat and protected areas. Prior to any tree removal, 691

trees will be carefully selected and removed outside seasonal bat activity from 1 No-692

vember and 31 March with a designated Biologist monitoring the removal of trees. Dur-693

ing construction, a speed limit of 10 mph will be required and construction workers will 694

be thoroughly informed and educated about the eastern massasauga rattlesnake in possi-695

ble habitats around the action area. Outside of these areas, a speed limit of 25 mph dur-696

ing construction and operation of the wind facility, FAA lighting will be applied and 697

controlled by motion detectors or infrared sensors, and scheduled tree trimming during 698

operation will be conducted outside the active period of Indiana bats. Lastly, between 1 699

April and 30 October of each year, turbines will be feathered from 30 minutes before 700

sunset and 30 min after sunrise until a designated cut-in speed is reached to reduce colli-701

sion mortality of Indiana bats. Compensatory mitigation that Buckeye Wind LLC in-702

cluded in the BO involve preservation of 217 acres (87.8 ha) of habitat within 7 miles 703

(11.2 km) of an Indiana bat hibernaculum in Ohio, or use an approved mitigation bank 704

within Ohio for the Indiana bat (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ohio Ecological 705

Services Field Office 2012, Buckeye Wind LLC 2013). 706

In conclusion, the Incidental Take Statement within the BO allows the take of 130 707

Indiana bats over the 25 year lifetime of the project as long as avoidance and minimiza-708

tion measures are met and compensatory mitigation is enacted within two years of the 709

25

permit being issued. If the taking of Indiana bats is exceeded, adaptive management and 710

re-initiation of federal consultation is required. 711

Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project: The largest project in Wyo-712

ming (WY), the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project (CCSM) covers 713

two wind farm sites totaling 1,000 turbines with a total capacity of 2,000 to 3,000 MW 714

and an anticipated 30-year project life. The project covers more than 227,638 acres 715

(112,000 ha) of mixed public and private land located about ten miles (16 km) south of 716

Rawlins, WY, in Carbon County, with a disturbance footprint approximately 1,500 717

acres (607 ha). Phase I of II is located in the westernmost part of the Chokecherry and 718

Sierra Madre Wind Development Area with the first 500 wind turbines being construct-719

ed, designed to provide 1,500 MW of wind energy (Power Company of Wyoming LLC 720

2012). 721

The wind facility would avoid a critical Sage-Grouse habitat and follow the BLM’s 722

and USWFS’s Avian Protection Plan to minimize impacts to Bald and Golden eagles 723

and other raptor species. CCSM is located within the Upper Colorado River Basin and 724

must follow the Recovery Implementation Program for Endangered Fish Species (also 725

known as the Recovery Program) and the Platte River Recovery Implementation Pro-726

gram (PRRIP). The BLM has determined that the project’s water depletions from the 727

Colorado River and Platte River system are “likely to adversely affect” fish species and 728

the Recovery Program addresses the conservation measures needed to reduce impacts 729

from the project. A programmatic biological opinion (PBO) for the PRRIP was created 730

for the region for a number of species but for the project development area, the whoop-731

ing crane (Grus americana) was of particular concern. 732

The whooping crane is the rarest of the world’s 15 crane species and has been feder-733

ally listed as endangered since 1967. The whooping crane has five areas within their 734

2,500 mile (4,023 km) migrational path federally designated as critical habitat; Aransas 735

National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) (Texas), Salt Plains NWR (Oklahoma), Quivirea 736

NRW (Kansas), Cheyenne Bottoms State Wildlife Area (Kansas), and the Platte River 737

valley (Wyoming and Nebraska). The population nests almost exclusively in Wood Buf-738

falo National Park (Canada) where nesting territories occupy poorly drained areas and 739

wetlands. The muskeg and boreal forests intermix and the cranes are able to nest in shal-740

low portions of ponds, small lakes, and wet meadows. Due to loss of wetlands from ur-741

banization, stress during migration, and nesting site specificity, the species nearly be-742

26

came extinct. However, many Recovery Programs, Federal Acts, and NWRs have 743

helped re-establish populations (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Field Supervisor of 744

Nebraska Ecological Services Field Office 2006). 745

The PBO for the Platte River Recovery Program allow the legal taking of six indi-746

viduals in the form of “harassment” in the region and one legal taking during the first 13 747

years of the PRRIP (which began in 2006). The incidental take of whooping cranes may 748

occur during habitat restoration or other land management activities, such as a wind 749

energy facility, which will require plans containing site specific measures to minimize 750

the effects of land management on federally listed species. The PBO has created “Rea-751

sonable and Prudent Measures” to minimize take, the first being to survey areas where 752

the whooping cranes migrate through in the Platte River valley and to schedule all activ-753

ities such as construction, operations, and maintenance, during times when the whoop-754

ing crane will not be disturbed or harassed (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Field 755

Supervisor of Nebraska Ecological Services Field Office 2006). 756

Due to the complexity of the PBO and nature of the Recovery Program, the PBO 757

serves several functions including consultation on future projects, implementation of 758

projects without exceeding the ITP of species, defining water-related activities and its 759

consultation process, and determining which aspects of the Program are and are not 760

within the PBO. The PBO Water Action Conservation Plan covers Colorado, Wyoming, 761

and Nebraska projects separately, but all aims to adopt water-saving measures to reduce 762