Final Thesis 1.1

-

Upload

robert-sroczynski -

Category

Documents

-

view

64 -

download

4

Transcript of Final Thesis 1.1

THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPLICATIONS

OF COAL MINING ON THE MID-WESTERN

REGION OF NSW

THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL

IMPLICATIONS OF COAL MINING ON

THE MID-WESTERN REGION OF NSW

Robert Sroczynski 3290501

Faculty of the Built Environment UNSW

Bachelor of Planning Thesis 2013

i

Abstract

The Mid-Western region of New South Wales, which has been traditionally known for

agriculture, viticulture and tourism has seen substantial increases in coal mining investment,

resulting in a total of four coal mines, two in the last ten years, with another four proposed.

This thesis investigates the economic and social implications of the construction and operation

of these coal mines on Mudgee and surrounding settlements. Through an analysis of the

existing literature, as well as statistical data and interviews with industry and academic

professionals, it becomes clear that the Mid-Western region is experiencing a mix of positive

and negative impacts caused by coal mining. The greatest impacts have been on the economy,

employment, infrastructure, housing, community wellbeing and safety as well as non-resident

workers and their families. Overall, the evidence suggests that on balance the Mid-Western

region has benefited from the coal mining industry. However, more time is needed to fully

monitor and better ascertain the full implications of a range of impacts in the long term and

whether the positives always outweigh the negatives. In the meantime there needs to be changes

to the existing assessment framework for coal mines in NSW so as to further mitigate the

negative impacts and strengthen the positive impacts.

ii

Acknowledgements

I would like to take this opportunity to give formal thanks and appreciation to my advisor Ian

Sinclair who provided substantial contribution to this thesis, pointing me in the right direction

and keeping me on track.

I would also like to thank Catherine Van Laeren, David Reid, Alison Ziller, Ben Harris-Roxas,

and all those who participated in the interviews, which provided me with substantial firsthand

information on coal mining, the planning system, and the potential impacts.

Lastly, I would also like to thank Richard Blake who helped me understand the geological

information relating to the formation of the Sydney Basin.

Front Cover: Coal train journeying through Wollar to the Port of Newcastle

Photo taken by Robert Sroczynski 2013©

iii

Table of Contents Abstract i

Acknowledgements ii

List of Figures iv

Introduction 1

Problem Setting 1

Problem Statement and Objectives 2

Methodology 3

Data Sources 4

Limitations 5

Structure 6

Chapter 1: Literature Review 7

Rural Development 7

Coal Mining Impacts on Rural Townships 8

Coal Mining as a ‘Temporary’ Rural Land-use 10

Chapter 2: Overview of the Mid-Western Region 13

Regional Overview 13

Location 13

Geology and Topography 15

Settlements 19

Socio-economics of the Mid-Western Region 23

Chapter 3: Economic and Social Impacts of Coal Mining on the Mid-Western Region 29

Impact on Regional Economy, Employment, Services and Infrastructure 29

Impact on Housing and Rental Availability and Affordability 48

Impact on Lifestyle, Community Safety and Wellbeing 56

Impact on non-resident work arrangements on workers and their families 62

Chapter 4: Coal Mining Assessment and Approvals in NSW 67

The Assessment and Approvals Process 67

Improving the Assessment and Approvals Process 75

Conclusion 79

Thesis Summary 79

Major Findings 79

Recommendations 82

Bibliography 83

Appendix 93

iv

List of Figures

Figure 1 Map of the Mid-Western LGA

Figure 2 Location of existing and proposed coal mines in the Mid-Western LGA

Figure 3 New South Wales Coalfields

Figure 4 Cleared plain near Wollar

Figure 5 Flatter terrain in the west of the Mid-Western region

Figure 6 Mid-Western region settlement hierarchy

Figure 7 Population of the Mid-Western region by town

Figure 8 The Wollar General Store

Figure 9 The abandoned Kandos Cement Works

Figure 10 Age pyramid of the MWRC

Figure 11 Growth in household income in MWRC

Figure 12 Growth in household income in NSW

Figure 13 Growth in household income in Wellington Council

Figure 14 Wollar Public Primary School

Figure 15 The below standard Ulan Road

Figure 16 The number of criminal offences reported to police in the MWRC from 2002 to 2012

Figure 17 Number of vehicles involved in crashes in the Mid-Western LGA and Wellington

LGA from 2004 to 2011

Figure 18 Heavy vehicle traffic on Ulan Road

Figure 19 Anti coal mine protest banners outside a residential rural property in Wollar

Figure 20 The MAC Narrabri

Figure 21 The NSW Mineral Exploration and Development Assessment and Approvals Process

for Major Mining Projects

1

Introduction

Problem Setting

Environmental and health concerns are a predominant planning conflict often central to the

assessment of many coal mines, and are the major focus of inquiry and scholarly literature. In

fact, there seems to be an inadequate amount of research into the holistic effects that coal

mining can have on rural townships in regional areas of New South Wales (NSW). While these

concerns are important, there is also an intrinsic need to understand the economic and social

impacts of coal mining that appear during the construction and operation of a coal mine. While

the mining of minerals and other resources, such as coal, lead and uranium, can promote

substantial economic growth, wealth and opportunity, mining can also result in unintended

consequences to the existing social and economic structures in the surrounding towns and

areas. A mine provides jobs, improvements in infrastructure and services, materials to support

other industries and a chance to create new wealth from the resources extracted from the

ground. However, mining can also cause environmental upheaval and degradation as well as

increased stress on limited infrastructure and services, housing affordability and availability,

existing social constructs, local economy structure and employment (Rocha and Bristow 1997).

The development of coal mines in NSW has had increased media coverage in recent years,

with much political and public debate surrounding the impacts of coal mines on the local

communities in which they operate. The decision by the NSW Land and Environment Court to

uphold an appeal to refuse a coal mine at Bulga has done much to publicise the potential for

mining to have a significant adverse impact on regional towns and the perceived shortcomings

of the current assessment and approvals process.

“The community should not have had to launch such a legal fight, but the state government and

the planning system failed to protect our rights - we had no alternative" (Lehmann 2013).

Research into the long term effects of coal mining near rural townships will allow planners to

anticipate these impacts and develop structures and plans to minimise the negative aspects and

foster the beneficial aspects. Currently, provisions within the NSW legislation planning

framework require consent authorities to consider the impacts a coal mine is likely to have on

the surroundings beyond the immediate site, including the consideration of social and economic

issues. Yet these less obvious local issues that are not so easily measured and observed are

often overlooked during the assessment process in favour of the overall ‘greater good’ the

2

development of a mine will bring to the state and national economies and industries. The

separation of the assessment process for coal mines in NSW between various government

departments can exacerbate the assessment process and lead to adverse economic and social

issues being overlooked and in some cases deliberately ignored.

Furthermore, the politics and priorities of the time can be a dominant factor in the determination

of a coal mine. It can be argued that the current system in place favours the development of

coal mines as they represent a substantial potential investment of capital benefiting the state

economy. This can be to the disadvantage of the interests of the local communities who may

be underrepresented in the decision making process due to their needs being seen as less

important. Thus, the essential question in coal mining assessment is balancing the benefit to

the many with the cost to the few.

Problem Statement and Objectives

The essence of this thesis is to explore the relationship between coal mining and the

surrounding townships in the Mid-Western region of NSW and determine whether the current

assessment and approvals process in place is effective in mitigating the economic and social

impacts concerning coal mining. The objectives of this thesis are to:

1. Examine the literature relating to the economic and social impacts of coal mining.

2. Determine what economic and social impacts are caused by coal mining.

3. Consider how planners and other professionals deal with the assessment of coal mines in

NSW.

4. Critically analyse the effectiveness of the current assessment and approvals process for

proposed coal mines in NSW.

5. Suggest improvements for the development of a better framework for assessing proposed

coal mines in NSW which addresses economic and social impacts.

3

Methodology

Literature review

A literature review was undertaken to contextualise the topic and assist to refine the key issues

and themes throughout chapters 4 and 5. The literature review was assembled to fulfil three

key functions for each of the topics mentioned. These are: to talk about the theories portrayed;

discuss the research methodology; and reveal any gaps or potential areas for further academic

research.

Qualitative in-depth interviews

Interviews were undertaken with key planning professionals, part-time academics and a coal

industry representative to gain professional opinion as to the effectiveness of existing

assessment provisions in mitigating social and economic impacts on the Mid-Western region

as well as a greater understanding of the impacts of coal mines.

Quantitative data

Statistical data gathered from government organisations was used to measure key demographic

and economic indicators in the Mid-Western region. These indicators were compared against

those from before the mine was developed and during the operation of the mine so as to

determine the effects of coal mining on the region and individual townships.

Case studies and fieldwork

Development applications for coal mines in the Mid-Western region were used for comparing

the perceived impacts determined during the assessment stage of development to the actual

impacts after the development had been completed and the coal mine was operational.

Analysis of information

Written analysis of data derived from Environmental Impact Statements for coal mines and the

Mid-Western Regional Council as well as from the in-depth interviews is done by contrasting

the economic and social environment which was present before an increase in the development

of coal mines with the environment afterwards. The nature of the analyses is evaluative as it

seeks not only to respond to the research objective of examining the economic and social

impacts which are caused by coal mining but, also to inform on ways of improving the

assessment and approvals process to better address these issues.

4

Data Sources

In order to fulfil the objectives of this thesis a broad collection of written materials and expert

knowledge regarding the effects of coal mining was required. Such material included:

Academic journals

A broad array of journal articles were derived from a range of publications, including,

Australian Planner, Environment and Planning, Journal of Environmental Planning and

Management, Journal of Land Use and Environmental Law, Journal of Planning History,

Journal of Planning Literature, Journal of the American Planning Association, Land Use

Policy and Mineral, Energy: Raw Materials Review and Journal of Rural Studies.

Specialist information

In-depth interviews were carried out with the following specialists:

Interviewee

number

Name Position/role

1 Catherine Van Laeren Director of Development and Community Services

at Mid-Western Regional Council

2 David Reid Managing Director of the Minnamurra Pastoral

Company

3 Ben Harris-Roxas Heath Section Chair at the International

Association for Impact Assessment

4 Alison Ziller Social planning consultant and a part-time

academic at the Universtiy of New South Wales

5 Confidential Coal mine employee in the Mid-Western region

6 Confidential Planning Consultant

7 Confidential Department of Planning and Infrastructure

representative

A copy of the Project Information Statement which was given to each interviewee can be found

in the Appendix.

5

Development application files and associated council and consultant reports

The majority of this material was accessed through the Department of Planning and

Infrastructure’s websites.

Planning documents and legislation

Mid-Western Regional Council planning documents and strategic plans, Mining Act 1992

Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 and State Environmental Planning Policies.

Newspaper articles

Predominately from the Sydney Morning Herald, The Australian and the Mudgee Guardian.

Statistics

Census data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, crime data from the NSW Bureau of

Crime Statistics and Research, and vehicle accident data from the Centre for Road Safety was

used.

Limitations

Given the time and financial constraints for this thesis it was not practical to extend the scope

of research to include an in-depth assessment of all of the economic and social impacts that

may have resulted from coal mining on the Mid-Western region. While it would have been

useful to gain additional data from surveys and questionnaires distributed to the local

community, the constraints set on the length of this thesis meant that a more detailed analysis

of the impacts was not possible. Furthermore, the distance of the study area from Sydney meant

that it was not feasible to carry out constant fieldwork, with time spent there having to be

carefully planned and executed in order to gain the most information possible. The large size

of the Mid-Western region further compounded this issue, adding to the costs associated with

carrying out fieldwork.

6

Structure

This thesis is comprised of a total of six chapters including this introduction.

Chapter 1 examines the literature relating to coal mine development and the associated

implications that such an intense land-use can have on surrounding townships.

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the Mid-Western region which will act as the area of focus

for the research into the impacts from coal mining development. It will investigate the

topography and geology as well as identifying the hierarchy of settlements in the region. The

economic, social and demographic profile of the region is also provided.

Chapter 3 offers an in-depth analysis of the wide ranging economic and social impacts that

coal mining has had on the Mid-Western region. The extent of the potential impact on the local

economy, employment, health and education services, roads, housing and non-resident workers

and their families is discussed against the backdrop of the region to better understand the

suitability of coal mining.

Chapter 4 presents the current process in NSW for assessing and approving the development

of coal mines. The effectiveness of this process is critiqued against the economic and social

impacts which are discussed in Chapter 3. Improvements to the assessments and approvals

process are then offered to address the economic and social issues inherent with coal

exploration and coal mine development.

The Conclusion examines the extent to which the economic and social implications of coal

mines impact the Mid-Western region, briefly examining the key findings and providing

recommendations for planning practitioners who are involved in the assessment and approvals

process for coal mines

7

Chapter 1: Literature Review

The purpose of this literature review is to explore the issues concerning coal mining as a rural

land-use. Broadly speaking, the topic covers the ways in which rural development occurs and

the social, economic and environmental impacts of coal mining on rural regional areas around

the world. This topic area is encapsulated through a series of primarily important issues and

relevant themes and concepts as depicted in a variety of scholarly literature which will form

the basis of this review, such as rural development, coal mining impacts on rural townships and

regions, and coal mining as a ’temporary’ rural land-use. As will become clearer, the literature

reviewed in this paper does not cover the entirety of the topic area, which has been deemed to

be pertinent. This has left some of the issues remaining unanswered, providing the foundation

for further research.

Rural Development

There is substantial literature on what ‘rural’ means, and what its significance is in an

increasingly urbanised society, with Denham and White (1998) illustrating that while the

proportion of the population in the United Kingdom that resides in urban areas is still ever

increasing, urban areas still take up a proportionately small amount of land. Read in isolation

from other sources on the notion of ‘rural’, the article is little more than a statistical analysis of

census data, however, when read with a much broader pool of relevant sources, Denham and

White set an important foundation on what rural areas essentially are. While Denham and

White (1998) focus on rural and urban statistics to define ‘rural’, Shuchsmith and Chapman

(1998) explore the notion of ‘rural’ from a sociological perspective and the negative effects

that rural living can have on individuals. Shuchsmith and Chapman (1998) help to show that

rural areas, aside from urban areas, can have their own set of social issues that arise from the

unique lifestyle.

The concept of development in rural areas, whether it be residential, commercial, industrial,

natural resource extraction, agricultural or infrastructure was a major literary focus in the 1980s

and earlier. Changes in the way rural settings were perceived during this period resulted in

new research being conducted. This was due to rural development beginning to extend beyond

those traditional notions of agriculture or resource based businesses to those of tourism,

recreation and niche manufacturers (Ward and Brown 2009). These traditional views expressed

in planning literature on development in rural environments have changed in the last 20 years,

from that of being a side note of ‘important’ urban development, to one of its own importance.

8

Ellis and Biggs (2001) details the changing themes in the last half century, from community

development to small farm growth to integrated rural development to market liberation to

participation and finally to Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers. Overall, Ellis and Biggs (2001)

have completed highly detailed and accurate research into changes to rural development.

The growing interest by governments and the private sector in developing regional and rural

areas is portrayed by Self (1990), who argues for a successful regional development policy,

debating the feasibility of investing in rural and regional areas. Self (1990) takes the view that

investment in rural areas is needed, “…investments in improved road and rail communications,

as well as contributions to the infrastructure costs…” (1990: 22). Furthermore, Chambers

(1983) takes the position that increasing development in rural areas increases the ability of

those who reside in these areas to participate in sharing their collective knowledge and

expertise to a wider set of society.

While these sources explain the reason to undertake rural development, they do little to explain

the reasons for there being underdevelopment in rural areas. The World Bank (1997) puts

forward that the reasons for the underinvestment in rural areas in developing countries is

because agriculture is a declining sector, the rural poor have little political power, urban elites

pursue policies that disadvantage the agricultural sector and resources have been concentrated

in the hands of the few. Further research is needed to determine whether the same reasons are

true for underinvestment in rural areas of developed countries.

Coal Mining Impacts on Rural Townships

A central theme that appeared from the literature is that the construction and operations of coal

mines has a multitude of positive and negative social, economic and environmental impacts on

rural communities. Cappie-Wood et al. (1979), while outdated identifies that coal mining will

always have negative impacts relating to environmental issues, urban expansion, conflicts with

rural industry and the transport and loading capacity. Franks et al (2010) gives examples of

coal mining case studies in the Bowen Basin and the commutative impacts on the surrounding

communities. The source draws conclusions from its research, such as “the expansion of coal

mining in the Bowen Basin has contributed to the generation of a number of cumulative

impacts, particularly pressure on social and economic infrastructure” (Franks et al. 2010: 301).

Bryceson and MacKinnon (2012), using an African context, examine the phenomena of mining

causing accelerated urbanisation in traditionally rural areas. This international perspective can

9

be useful for both developing and developed countries as the concepts explored are transferable

between different sized economies.

A common theme that emerged from the literature was that the use of fly-in fly-out (FIFO) and

drive-in drive-out (DIDO) workers in the coal mining industry and housing them in out-of-

town work camps has created a culture of masculinity, encouraging alcohol and drug induced

violence and crime (Carrington et al. 2010; Carrington et al. 2011; Carrington et al. 2012;

Doukas et al. 2008; Storey 2010). As well as detailing a variety of social and economic impacts,

Carrington et al. (2011) discusses how these initial issues, such as housing unaffordability,

increased wages, and gender imbalance can result in subsequent issues, such as a rise in crime

and violence. “A sudden rise in disposable income can lead to higher rates of alcohol and

drug abuse, gambling and other forms of conspicuous consumption and indebtedness”

(Carrington et al. 2011: 340). Carrington et al. (2011) shows that rapid population increases in

small rural resident communities can lead to pressures on the existing social fabric. “It is the

relative scale and pace of socio-demographic change that can produce social disorganisation

and dislocation in communities” (Carrington et al. 2011: 339).

As the effects of FIFO and DIDO workers in the coal mining industry have become

increasingly apparent and widespread over the past 15 years, the variety of literature focused

on the use of these practices has grown. Storey (2010) suggests that as mining investment in

Australia has significantly increased since the modern mining boom took off in early 2000, the

once isolated problem of using FIFO and DIDO workers and housing them in out of town work

camps, is now being experienced by townships across Australia. As the literature suggests, this

is a departure from previous FIFO practices which had been traditionally confined to the far

off regions of outback Australia (Storey 2010). Such is the severity of those affected, the House

of Representatives Standing Committee on Regional Australia commissioned a report, ‘The

Cancer of the bush or salvation for our cities? Fly-in, fly-out and drive-in, drive-out workforce

practices in Regional Australia’, which provided recommendations for reducing the impacts of

such practices on existing towns (Commonwealth of Australia 2013a).

Gillespie and Bennett (2012) discuss how there is a need to integrate the assessment of

environmental, social and cultural impacts that result from coal mining, as opposed to the

system currently employed which involves assessing the three in isolation. The source agrees

that while coal mining has some positive benefits to rural communities, such as job creation

and infrastructure, there are a number of environmental, social and cultural impacts that need

10

to be assessed and addressed with each proposed coal mine. Rolfe et al. (2007) explores the

view that coal mines can on one hand foster improvements in social conditions and on the other

hand create offsetting economic and social consequences.

The idea that “as agriculture declines in importance, coal mining in particular is increasing

in importance…[causing] crucial economic and social effects, increasing social and cultural

divisions in the community” is explored by Perlgut and Sarkissian (1985: 14). This leads to

more questions such as: is the government doing enough to ensure that the social, economic

and environmental issues being adequately assessed in the planning process? A few of the

sources identify conflict resolution strategies for mine management, which would help to

reduce long term negative impacts on rural communities (Hilson 2002).

Coal Mining as a ‘Temporary’ Rural Land-use

A central theme that emerges from the literature is that coal mining and mining in general is a

‘temporary’ rural land-use. Increased participation by the coal mining industry is needed during

mine downscaling and closure to reduce the negative impacts on the region.

The World Coal Institute makes a poignant remark, stating that “…mining is only a temporary

land use. Mine rehabilitation means that the land can be used once again for other purposes

after mine closure” (2005). It is for this reason that the majority of literature that exists about

the rural development of coal mining explores the impact on these rural areas when individual

coal mining operations cease (Acquah and Boateng 2000; Morrey 1999; Rocha and Bristow

1997; Warhurst et al. 1999). Morrey (1999) mainly focuses on the economic reasons for coal

mine closure, however, included in the aims and objectives of mine closure are the need to

maintain appropriate levels of air quality, the protection of surface and groundwater resources,

and the reclamation of land for agricultural or ecological production. Furthermore the need to

include objectives for socioeconomic factors and cultural resources as planning components

for the mining industry is addressed. Morrey (1999) cites the World Bank and Berlin

Guidelines for operations closure. It should be noted that a large focus of Morrey’s (1999)

article is that there are financial, incentive driven mechanisms to promote ongoing mitigation

which can reduce expensive remedial work needed once coal extraction operations have

ceased.

11

Rocha and Bristow identifies that mining has a significant impact on the natural and human

environment and that there are long term effects that result from mine downscaling and closure

on human beings and their society (1997: 15). Rocha and Bristow (1997) go on in the article

to give examples of the effects that mine downscaling have on communities, such as direct job

retrenchment for locals and indirect job losses as a result of businesses which rely on services

to the mine’s employees. Equally so, “Mining can also contribute to the process of creating

sustainable economic development by making provisions for the socio-economic well-being of

the communities affected once the mineral resources are depleted” (Rocha and Bristow 1997:

16).

Practical solutions to these negative impacts of mine downscaling and closure are presented by

Rocha and Bristow, such as reskilling the mine workforce, establishing small and medium

businesses, continued utilisation of infrastructure, and fostering tourism (1997: 18-19). Instead

of only focusing on the negatives, it provides answers to the problems. Warhurst et al (1999)

further examines, in great detail, the impact of mine closures on individuals and the community

and then conducts an analysis of best practice and future trends in coping with closure.

Conversely, Acquah and Boateng (2000) focused on the environmental impacts in Ghana for

mine closures, giving little attention to the possible socio-economic and cultural impacts. The

only reference to impact to the community being:

“Long after the mine has closed certain social changes introduced into

nearby communities will continue to operate and amenities such as

infrastructure for potable water will begin to break down. The

company will undertake to train the youth in the communities to

establish small-scale enterprises so that when the mine has closed

these communities will not disintegrate.” (Acquah and Boateng 2000:

27).

It is to be noted that Warhurst et al. also conducts an analysis of constraints for transferring

best practice, coming to the conclusion that, ”Many of the practices are contingent on the early

warning or identification of closure” (1999: 24). It is important that this article includes the

constraints and limitations to reducing socioeconomic impacts of mine closures as it gives

grounding and a sense of reality to the source.

12

Lockie et al is able to illustrate the negative impacts associated with a temporary land-use such

as a coal mine, by employing the resource community cycle:

“The resource community cycle draws explicit attention to the interplay

between economic growth and decline, workforce and infrastructure

decision-making, population dynamics and social capital. In doing so,

it shows decisions made prior to the implementation of a project have

ongoing ramifications that, in the New Zealand case, have been shown

to impact on a community's ability to cope with and move on from

periods of economic stagnation in particular resource industries”

(2009: 331).

Lockie et al. (2009) further state that if appropriate measures are not implemented by the

mining company then as the mine winds down and eventually closes, the single industry culture

resists change, resulting in a period of recession or depression in the community.

The array of issues surrounding the concept of coal mining as a rural land-use, such as the ways

in which rural areas are developed and the social, economic and environmental impacts that

coal mining has as land-use on the rural environment, and the long term issues resulting from

coal mining being a ‘temporary’ rural land-use are divulged into in varying degrees of detail in

the explicit research cited. There is a lack of qualitative research literature regarding the

perceived impacts of coal mines from the perspective of rural communities. Further qualitative

research is needed to be carried out in order to assist in answering whether coal mining is a

suitable, sustainable land-use in rural environments. As the literature explored in this review

suggest, there are a multitude of social, economic and environmental longevity issues that come

about as a result of coal mining exploration, development and closure, as well as there being

an inverse connection to the long term security of agricultural industrial activities. The extent

to which these issues identified in the literature have impacted on the Mid-Western region will

be discussed later in Chapter 3.

13

Chapter 2: Overview of the Mid-Western Region

It is important to understand the Mid-Western region of NSW in order to fully comprehend the

implications of the development and operation of coal mines. This chapter will introduce the

Mid-Western region, including its topographical and geological characteristics and its location

in relation to the rest of NSW. The historic changes in social, economic and environmental

aspects, as too the changing demographics, will be explored in order to better appreciate the

contemporary economic and social issues facing the region and how these have changed over

time. Additionally, there will be an overview of the differing purposes of the centres within the

region, as well as the socio-economic makeup of the region as a whole.

Regional Overview

Location

The Mid-Western region is located in the central west of NSW being approximately 250km

from the centre of Sydney and for the purposes of this thesis incorporates the area identified

within the Mid-Western Regional Council (MWRC) Local Government Area (LGA). “The

Council area stretches from the Wollemi National Park in the east to Lake Burrendong in the

west, and from the Goulburn National Park in the north to the Macquarie and Turon Rivers in

the south”, and, according to the MWRC, the LGA encompasses an area of 9,000km² (MWRC

2010a:3). The LGAs surrounding the Mid-Western region are Warrumbungle LGA to the

northwest and Upper Hunter LGA to the northeast, Wellington LGA to the west and

Muswellbrook LGA to the east, Cabonne LGA to the southwest and Singleton LGA to the

southeast, and Lithgow LGA to the south. In March 2004 there was a redistribution of the

boundaries of some NSW LGAs and an amalgamation of others. The new Mid-Western

Regional Council comprises 100 per cent of the former Mudgee Shire, 70 per cent of the former

Rylstone Shire and 10 per cent of the former Merriwa Shire (Wells Environmental Services

2006a: v). Figure 1 below illustrates the boundaries, settlements, surrounding LGAs, defining

natural features of the Mudgee region, as well as locating the region in the context of NSW.

The significance and current role of these settlements will be discussed in greater detail in the

Settlements section of this chapter.

14

Figure 1: Map of the Mid-Western LGA (Source: Adapted from MWRC 2010a:3)

15

Figure 2 below plots the existing coal mines within the Mid-Western LGA, Ulan (1982),

Moolarben (2010), Wilpinjong (2006), and Charbon (1980), as well as the proposed coal

mines of Mt. Penny (2013), Cockatoo (2016), Cobbora (2014), and Inglenook (2016). As

shown in Figure 2, the majority of the existing and proposed coal mines in the LGA are

within 60kms of Mudgee.

Figure 2: Location of existing and proposed coal mines in the Mid-Western LGA (Source: Van Laeren 2012)

Geology and Topography

As this thesis concentrates on the economic and social implications of a specific land-use, coal

mining, it is important to ascertain the geology of the region to understand why it is suitable

for both mining and agriculture/animal grazing. According to the NSW Department of Trade

and Investment (DTI), some 60% of NSW is covered by sedimentary basins, comprising of

gas, minerals and/or coal (2013). Figure 2 below identifies some of the different coalfields of

NSW within their respected sedimentary basins, including the Western Coalfields which is the

location of the Mudgee region. As the map illustrates, the vast majority of the coal reserves in

NSW are located within this 500 kilometre ‘Sydney – Gunnedah –Basin’.

16

Figure 3: New South Wales Coalfields (Source: NSW Department of Trade and Investment 2013a).

The Geological Survey of New South Wales (GSNSW) is the primary geoscience agency for

the NSW DTI, which provides information to not only the government, but also the exploration

and mining industries and the wider community regarding the state's geology. The GSNSW

prepared a report, The Geological Evolution of New South Wales - A Brief Review, which

details the geological evolution of NSW based on plate tectonics (Scheibner 1999). The report

details that during the late Carboniferous to Triassic period (330 – 205 million years ago), a

continental rift formed west of the New England region leading to volcanic activity and

eventually forming a large transitional ‘Sydney Basin’. This basin slowly filled up with organic

sediments, most likely from a series of swamps or large still to slow moving bodies of water.

Over time tectonic movements in the region caused mountain building, loading the region with

17

a lot more rock which transformed it into the ‘Sydney – Gunnedah – Bowen Basin’ more or

less seen today. During the mountain building and subsequent downwards pressure, the organic

sediment was compacted over millions of years, eventually forming coal. As the report

concludes, “the [resulting] coal measures of the foreland basin, the ‘Sydney – Gunnedah –

Bowen Basin’, contain the main black coal deposits in Australia” (Scheibner 1999: 27-28).

This process has led to a diverse geological make-up that is well suited to coal extraction as

well as mineral extraction due to the large volcanic activity in the region, “The widespread

igneous activity and metamorphism in the New England region produced a large range of tin,

tungsten, molybdenum, antimony and gold deposits” (Scheibner 1999: 28). Due to the

continent of Australia forming, comparably much earlier than the other continents, there has

been a lot of soil weathering and leeching, making much of Australia’s soil nutrient poor.

Previous mountain building and successive volcanic activity in the Mudgee region has made

the soil rich in minerals, greatly increasing the ability to support plant growth and sustain

agriculture and intensive animal grazing (Chapin III et al. 2011: 6).

The geological transformation of the region has led to large coal reserves in the northeast,

where three existing coal mines, Ulan, Moolarben and Wilpinjong are located. According to a

geological overview written by the GSNSW, “There are many areas where cumulative coal

thickness is well in excess of 20 metres, and numerous individual seams with reservoir

thickness greater than 2 metres” (NSW Department of Trade and Investment 2013b). The

effect that the presence of these minerals and coal has had on the regional economy will be

discussed in the Socio-economics section of Chapter 2.

The Great Diving Range runs through the Mid-Western region, dividing the region between

the central-west catchment in the west and the central rivers catchment in the east. The Ulan,

Moolarben and Wilpinjong coal mines are spread between these two catchments. Many of the

settlements in the region rely on the groundwater extracted from rivers, lakes and aquifers from

these catchments as their principle water supply. There has been a continued demand for

surface water by residents, agriculture and industry coupled with reduced rainfall. This has led

to significant pressure on the water catchments, “The demand for groundwater extraction,

particularly for irrigation, is increasing and placing additional pressure on aquifers and

ecosystems” (CWCMA et al. 2012: 44). Many of the Councils within the CWCMA are

currently preparing Integrated Water Cycle Management Plans to address water policy issues

18

through initiatives such as stormwater management, recycling and reuse of water, demand

management, and more holistic water restrictions (CWCMA et al. 2012).

According to the Central West Catchment Management Authority (CWCMA) there are three

types of landforms found in the Mid-Western region, “Broadly, these can be grouped into

tablelands, slopes and plains, reflecting the influence of the Great Dividing Range in the east

through the slopes to the floodplains of the west and the north-west.” (CWCMA et al. 2012:

12). Since European settlement began in the early to mid-19th Century many of the plains in

the region have been cleared of trees and natural vegetation for animal grazing and agriculture

(Department of Sustainability Environment Water Population and Communities (2010). This

has left isolated sections of dense wooded areas in the east and south of the region, generally

where the elevation is higher and the land less suitable for clearing, such as on steep slopes and

on and around rocky outcrops. Figure 4 below shows an example of a cleared plain in the

northeast of the region and the surrounding slopes and peaks of the Great Dividing Range

which have been left uncleared, making them a habitat for fauna. The coal mining in the region

has generally been limited to these plains in the east, as the level of excavation needed to reach

the coal seems is less extreme and therefore more economical on the flat terrain.

Figure 4: Cleared plain near Wollar (Source: Sroczynski 2013a)

19

Figure 5 below demonstrates the typical topography of the region as you move further

northwest from the Great Dividing Range. As the landscape levels out, the proportion of land

devoted to large natural wooded areas is far less than that of the eastern and southern parts of

the Mid-Western region.

Figure 5: Flatter terrain in the west of the Mid-Western region (Source: Sroczynski 2013b)

Settlements

According to the Mid-Western Regional Council Comprehensive Rural Land Use Strategy

there are 19 settlements in the Mid-Western region ranging from large centres, consisting of

hundreds of dwellings, to small villages having only a small grouping of dwellings (2010).

Each of these settlements provide services and amenities to the residents of the Mudgee region

specific to their importance, proximity to other settlements, and population. A summary of the

settlement hierarchy for the Mid-Western region can be seen in Figure 6 below. Figure 7 below

illustrates the proportion of the regional population that reside in each settlement.

20

Figure 6: Mid-Western region settlement hierarchy (Source: Mid-Western Regional Council 2010b: 16)

21

Figure 7: Population of the Mid-Western region by town (Source: Mid-Western Regional Council Business and

Economic Profile 2010a: 5)

The largest centre in the region is Mudgee, sitting at the top of the settlement hierarchy, with a

population of 9,830 and approximately 4,346 dwellings (ABS 2011a). Mudgee acts as a district

centre for the LGA, providing much of the larger retail, health, education and employment

services, and entertainment for the surrounding area. The centre is the home to the Council

chambers and offices, a public high school, several pubs and a range of retail stores and

machinery facilities. However, due to its limited size and development, Mudgee relies on the

regional centres of Dubbo, Orange, and Bathurst in the surrounding regions, which act as the

principal points for business, government, education and health services.

The smaller centres in the region which support Mudgee are Gulgong, Rylstone and Kandos,

with populations of 1,866, 624, and 1,284 respectively (ABS 2011a). These towns act as local

centres for different parts of the LGA, providing services which are needed on a more regular

basis, such as limited retail, food, educational services, entertainment and groceries. As well as

Gulgong providing these services, it also serves a cultural and historical function, having

retained much of its original buildings and architecture. This retention of such historical value

has led to Gulgong becoming a tourist attraction to those visiting Mudgee or travelling through

the region. Rylstone and Kandos too have historic value, but also provide health and

educational service. For example, Rylstone has a hospital, while Kandos has a high school. As

the two towns are relatively close to one another, being 6.9km or 7 minutes by vehicle, each

provides a range of services that can be shared between the residents of each of the towns.

22

The villages of Bylong, Birriwa, Charbon, Clandullar, Goolma, Lue, Hargraves, Hill End,

Ilfrod, Pyramul, Sofala, Turill, Ulan, Windeyer, and Wollar have varying populations and in

some cases consist of just several dwellings (ABS 2011a). These villages act as a limited local

point, in some cases having a public primary school, general store, and/or pub. Figure 8 below

shows the Wollar General Store, which is an example of one such local shopping facility. As

the means of fast and convenient transportation has become more available over the last 150

years, the significance of these villages has declined. Furthermore, these areas have become

less populated as people have migrated to larger centres and cities in search of employment. In

some instances this has resulted in villages becoming abandoned and converting into localities,

rather than settlements. These small rural localities are scattered throughout the region acting

as a central point for the local community. They generally do not have any retail or services

other than a hall, church or bushfire facilities.

Figure 8: The Wollar General Store provided petrol, diesel and limited grocery products (Source: Sroczynski

2013c)

23

Socio-economics of the Mid-Western Region

The Mid-Western region has a diverse economic and social fabric with a strong multilayered

economy which has sustained a high level of economic and population growth as well as a

solid community bond. Much of the data on the socio-economics of the region have been

sourced from the 2011 Census. The Mid-Western Regional Council Business and Economic

Profile (2010a) has also provided a plethora of useful data on the social and economic makeup

of the region. It is important to understand the demographics of the region over a relative period

of time, such as over three consecutive Censuses, so that changes resulting from the

development of the coal mines can be clearly isolated and identified. These changes in the

measurable data will be analysed in greater detail in Chapter 3.

According to the Mid-Western Regional Council Business and Economic Profile the major

industries of the Mid-Western region are agriculture, mining, tourism, and viticulture (2010a:

3). The Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011 Census data for Industry by Employment for the

MWRC lists the following industries as having the highest employment in descending order:

Mining – 1,311 (13.95%)

Retail Trade – 1,045 (11.12%)

Agriculture, forestry and fishing – 878 (9.34%)

Healthcare and social assistance – 862 (9.17%)

Construction – 762 (8.11%)

Accommodation and food service – 754 (8.02%)

Education and training – 676 (7.19%)

This employment by industry census data supports the Business and Economic Profile,

showing that these sectors listed above provide goods and services, as well as technical skills

directly or indirectly to the mining, tourism and/or agriculture/viticulture industries. Whilst

coal mining has grown in economic importance over the last 10 years in the Mid-Western

Region, tourism, agriculture and viticulture still contribute a large part to the regional

economy. According to the Business and Economic Profile, more than 460,000 tourists visit

the region annually with 600 businesses in the Mid-Western Region involved in the tourism

24

industry (MWRC 2010a: 8). Furthermore, “Approximately 38 percent of registered

businesses in the Region are part of the agricultural sector”, contributing $50.5M in gross

value production in 2006 (MWRC 2010a: 9). Also, while the viticulture industry has adapted

to the worldwide over supply of grapes by reducing wine production, it remains a strong

sector helping to attract tourists and investment into the area (MWRC 2010a:9).

The present-day significance of the mining sector in the region can be best demonstrated by

looking at its growth between 2001 and 2011. During this period those employed in the

mining industry has grown by approximately 231%, which is 23% annually (ABS 2011a).

This is in contrast to the agriculture, forestry and fishing industry which has declined by

approximately 33% over the past 10 years, which is -3% annually (ABS 2011a). This shift is

possibly indicative of an increase in the number of residents being employed by the mining

industry in the region through the development of the coal mines post 2001.

Two large employers in the region have closed in the last 10 years, the Mudgee Regional

Abattoir closing in 2003 with the loss of 230 local jobs and the Kandos Cement Plant closing

in 2011 with the loss of 98 local jobs. The effects of these closures have had the greatest

impact on the Kandos area, with the Western Advocate Newspaper reporting that the plant

closure will have a devastating impact on Kandos and the surrounding region in the long term

(2011). Nevertheless, the unemployment rate in the LGA is 5.6% and 5.9% in the rest of

NSW, suggesting that there is still excess capacity in the job market for employment in the

region (ABS 2011a). The economic and social impacts of the abovementioned industry shift

being experienced in the region will be discussed further in Chapter 3.

The demographics of the MWRC typify the standard rural regional area of NSW, highlighting

the many issues facing these non-metropolitan areas. A selected summary of statistics taken

from the 2011 Australian Census shown below highlights key information for the Mid-Western

region:

Median age of persons (years) – 41

Median total household income ($/weekly) – 938

Median mortgage repayment ($/monthly) – 1,551

Median rent ($/weekly) – 200

Average household size – 2.4 persons

25

Figure 9: The abandoned Kandos Cement Works (Source: Sroczynski 2013d)

The ABS data for the LGA shows that the majority of the MWRC population is of Australian

birth, being 84.88%, with the next highest proportions being from the United Kingdom, 3.13%;

New Zealand, 1.04%; and Germany, 0.41% (2011a). This is reflected in the language spoken

at home with 91.65% of the population speaking only English and 0.29% of the population

speaking German. Additionally, 79.37% of the population identifies with the Christian faith,

reflecting the European cultures from which the majority of the LGA originated. Concerning

education, approximately 13% of the population have undertaken some level of higher

education beyond school, ranging from Certificates to Post Graduate Degrees.

As can be seen in Figure 10 below, the greatest proportion of residents in the LGA are those

aged between 45 and 84 years, comprising 42.5% of the population compared with 38.2% of

the NSW population, with the medium age being 41 and 38 respectively (ABS 2011a). While

the number of children aged under the age of 15 is 20.6% in the Mid-Western LGA and 19.3%

of the NSW population, the proportion drops to 10.8% for those 15 to 24 years of age in the

Mid-Western LGA and 12.9% of the NSW population. The large drop in the number of

26

teenagers and young adults in the Mid-Western LGA suggests that children leave the region

when they are of an age to do so, possibly to attend at higher education institutions or to find

employment in the larger regional centres or capital cities.

Figure 10: Age pyramid of the MWRC (Source: ABS 2011a)

The family composition of the Mid-Western Region is summarised in the table below, which

shows that couple families with children make up the largest proportion, being 44.8% of the

population which is lower than the rest of NSW, which is 48.4%. Couple families with no

children make up 39.7% of the Mid-Western region’s population, compared to the rest of NSW

which is 34.4%. That the proportion of couple families with no children is higher than the rest

of the state and the proportion of couple families with children is lower than the rest of the state

supports the earlier statement in which the children leave the LGA once old enough, leaving

an older population, with less teenagers and young adults.

The differences between the growing larger centres such as Mudgee, Gulgong, Rylstone and

Kandos and the smaller declining settlements can be quite extreme. These socio-economic

differences between different types of settlements in the region can be exemplified using the

example of the village of Wollar. Wollar is a small village located 48 kilometres from the town

of Mudgee with a population of 260, including the surrounding gazetted area (ABS 2011a).

Lynne Robinson a former Wollar local and Mudgee Historical Society research officer said the

-5.0% -3.0% -1.0% 1.0% 3.0% 5.0%

0-4

5-9

10-14

15-19

20-24

25-29

30-34

35-39

40-44

45-49

50-54

55-59

60-64

65-69

70-74

75-79

80-84

85+

Axis Title

Age

Females Males

27

town was, “Once a bustling commercial hub servicing large pastoral leases in its heyday from

the late 1800s to the mid-1900s” (cited in Noone 2011).

Past its heyday, Wollar now has only a general store which also serves as a petrol/diesel station

and a public primary school with, “Only seven pupils at the school…and five of those are from

one family” (Reid, D 2013, pers.comm., 16 August). Interviewee 5, who was a landowner in

the Wollar area and now an employee a local coal mine in the region, believes that Wollar has

been declining for the last 50 years.

“…an area which has been declining ever since I’ve known it and quite

rapidly. When I first knew it, it had 50 members in the tennis teams, it

had a full cricket team with many more reserves. The school had 15

people, etc., etc. And there was a dance every month in the hall. But if

you had a closer look at it, they were all the older people still. Well as

they died out, the younger ones moved away. So by the time we came

along, one of the first things I had to organise for Wollar was pay for

the insurance on the hall because the locals couldn’t do it. And it got

down to the stage where it was really battling… Basically, your three

main types have been your older people that have been associated with

Wollar for a long time. There are very few of those left. Then you had

people who came in; old people who could not afford anywhere else, so

they bought in Wollar because it looked like a nice little place. And then

you had the people come in…the [19]70s, [19]80s and [19]90s. A lot

of those were people trying to escape the Vietnam War. And so you had

a big drug culture. Not doing any harm, but they lived in their own little

world…And because Wollar was so far out nobody took any notice of

them...” (Interviewee 5 2013, pers.comm., 25 August).

Some of the reasons for villages such as Wollar experiencing negative population growth and

a withdrawal of services, has already been briefly discussed in the Settlements section of this

chapter, such as improvements in transportation and search for employment. However, as

Interviewee 5 mentioned in the interview quoted above, the changing demographics and social

issues have had a significant effect on the village.

28

With the opening of the Wilpinjong Coal Mine in 2006, the majority of the surrounding land

was purchased by the mining parent company, Peabody, including the majority of village of

Wollar. David Reid, the Managing Director of the Minnamurra Pastoral Company which has

large land holdings in the surrounding region and has worked closely with a local coal mine

suggested in an interview that the mining company was trying to revive the village.

“[The mining company] were quite open about their concerns about

the effect they would have on Wollar as a village and they were trying

to make sure that the whole thing didn’t close down…So they bought up

a lot of the houses there and did them up so that people could rent. A

lot of the miners live there now” (Reid, D 2013, pers.comm., 16

August).

Having familiarised the reader with the Mudgee region’s location, geography, and basic socio-

economics it is important to investigate the effects that the development of the Ulan,

Wilpinjong, and Moolarben coal mines in the region have had on the towns and smaller

settlements. Chapter 3 will investigate, specifically, the social and economic impacts that have

resulted from the development and continued operations of these coal mines on the surrounding

Mudgee region, including the impacts of supply and demand. Further to this it will explore

what effect the running down and eventual ceasing of mining operations could have on the

towns and settlements in the region.

29

Chapter 3: Economic and Social Impacts of Coal Mining on the Mid-

Western Region

The beginning of the resources boom in Australia during the mid-2000s started a significant

endeavour to expand the coal mining production capacity of NSW through the development of

new coal mines and the expansion and/or recommissioning of existing coal mines across the

state (Bishop et al. 2013). The race to benefit from this resource boom resulted in a range of

widespread economic and social impacts on the regional communities that would have to

support these mines. The Mid-Western region, which has been traditionally known for its

agriculture and viticulture, is one such area that has seen dramatic positive and negative impacts

brought on by the mining boom. This chapter will investigate the economic and social impacts

on the Mid-Western region through an analysis of quantitative data from ABS statistics and

qualitative data derived from in-depth interviews undertaken with key industry and planning

professionals. These impacts experienced by the Mid-Western region have been separated into

four key sections. The first section explores the impact on the regional economy, employment,

services, and infrastructure. The second section delves into the impact on housing and rental

availability and affordability. The third section examines the impact on lifestyle, community

safety, and wellbeing. The final section will look at the impact on non-resident work

arrangements on workers and their families.

Impact on Regional Economy, Employment, Services and Infrastructure

The construction and operation of coal mines in the Mid-Western region has resulted in a

number of positive and negative economic and social impacts on the regional economy,

employment services, and infrastructure. The rapid expansion of the resource extraction in the

region from two coal mines, Ulan and Charbon, in the 1980s to currently four mines and

another four proposed, has led to a changes in the regional economy, shifting some investment

from agriculture and viticulture, to mining and its various supporting industries and services.

This shift in the regional economy has led to increased pressures on roads, rail, water,

electricity, and health and education services, while at the same time improving employment

opportunities for a large number of the local population. There is an ever growing need to

balance and mitigate the adverse impacts with the advantageous impacts that can be attributed

to the coal mines in the Mudgee region. This section will identify and discuss these impacts of

30

the coal mines in the Mudgee region by concentrating on statistical changes and information

obtained from key literary and primary sources. Table 1 below lists the main coal mining

impacts in the Mudgee region which will be discussed throughout this chapter.

Table 1: Examples of coal mining impacts

Source: Adapted from Franks et al. 2010

The Moolarben and Wilpinjong coal mines started operating post 2004 and between then and

2012, there has been a trend taking place across Australia in which:

“Mining’s contribution (in terms of Gross Domestic Product, or GDP)

has doubled [in Australia],

Australia’s mining exports have doubled in nominal terms, but only by

40 per cent in price adjusted or volume terms.

There have been unprecedented levels of investment in new mining and

energy developments (and related infrastructure) resulting from the

strong profits in mining industries.

The strong FIFO/DIDO demand has lifted revenue growth in the

accommodation and domestic (regional) aviation industries” (Pham et

al. 2013).

Examples of Negative Impacts Examples of Positive Impacts

Price inflation (e.g. housing and rents) and

the disproportionate impacts on residents

not employed in the mining industry.

Increased employment and economic

investment.

Overloading of existing social services (e.g.

childcare, healthcare and education).

Regional and community development

benefits from mine community investments.

Reduced water quality (e.g. saline discharge

into rivers).

Local business development from mine

procurement.

Reduced water quantity (groundwater draw

and water table impacts from multiple

mines and industries).

Greater royalties and taxes to the State

Government and increased rates to the Mid-

Western Regional Council.

Traffic congestion and road surface

degradation.

Road and infrastructure upgrades.

Lack of State Government investment in

services and infrastructure upgrades.

Population increases that create a critical

mass for better services and infrastructure

(e.g. schools, and sporting teams).

31

The socio-economics section in Chapter 2 briefly discussed the shifting economy of the Mid-

Western region and how the coal mines are contributing to an increasingly large part of the

economy in terms of employment, investment and production. During the period between 2001

and 2011, those employed in the mining industry grew by approximately 231%, compared to

the agriculture, forestry and fishing industry which has contracted by approximately 33% (ABS

2011a). According to David Reid, this change is a result of the ability of the mining industry

to induce employment with more attractive remuneration packages from those offered by the

agriculture sector. “The mines pay much higher wages which agriculture could never match,

so there has been a movement away [from the industry]…It makes it very hard for properties

in the area to find young people who are prepared to work” (2013, pers.comm., 16 August).

David Reid goes further, concluding that this is not isolated to only agriculture, but is a common

theme across many industries in the region, “…tending to push wage levels higher which makes

it hard to contain wage bills” (2013, pers.comm., 16 August). He gives an example of the

difference between the wages that he is able to offer to employees on his cattle farm from those

being offered by the mining companies in the area.

“We had a stockman who was earning $50,000 or $60,000 a year with

us, he got a job [with the mine] and was easily putting away $120,000

a year [$2,300 per week] after tax. So more than double what we could

pay” (Reid, D 2013, pers.comm., 16 August).

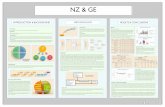

Figure 11 below shows that the number of household incomes in the MWRC earning above

$2,500 per week has grown from 2.60% in 2001 to 21.34% in 2011, equating to a seven fold

increase. When this is compared with the proportion of households in NSW earning above

$2,500 per week, as seen in Figure 12 increasing from 6.67% in 2001 to 28.22%, this does not

seem abnormal. However, when the wage increases in the Mid-Western LGA are compared

with a largely agricultural economy like that of the Wellington LGA, which has no coal mines,

isolated conditions which have led to this wage increase in the Mid-Western region become

clear. Figure 13 below shows the proportion of households earning above $2,500 per week in

the LGA of Wellington Council increasing from 1.28% in 2001 to 10.08% in 2011, which is

almost 12% lower than the rise in income of those living in MWRC over the last 10 years.

32

Figure 11: Growth in household income in MWRC (Source: ABS 2011a)

Figure 12: Growth in household income in NSW (Source: ABS 2011b)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2001 2006 2011

Total Family Income for MWRC per Household

(Weekly)

Less than $799 $800 - $1,499 $1,500 - $2,499 More than $2,500

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2001 2006 2011

Total Family Income for NSW per Household

(Weekly)

Less than $799 $800 - $1,499 $1,500 - $2,499 More than $2,500

33

Figure 13: Growth in household income in Wellington Council (Source: ABS 2011c)

That there has been such a large increase over the last 10 years in the number of workers in the

Mid-Western region employed in the mining industry suggests that this rise in higher incomes

is due to this growing sector, which is able to offer significantly higher wages than other

traditional regional industries due to the mining industry’s ability to attract investment dollars

(Pham et al. 2013).

While this large increase in the number of households in the MWRC earning over $2,500 per

week has benefited those on higher incomes, it has in some instances had disproportionate

impacts on those households on low incomes. Interviewee 5 submitted that there have been

those within the Mudgee region who have capitalised on this ‘new wealth’, by charging

customers comparably higher prices than those regional centres that are not directly supporting

the coal mines. However, he raised the question of whether this is necessarily caused by the

mines or rather the greed of people that will exploit what the mine has brought in.

“A classic example of that is the other day I had ordered for my Ute a

new side vision mirror. My local mechanic rang me back, laughed and

asked if I wanted to pay $145 or $195? I said that’s obvious isn’t it?

Well for $145 he could get it in from Dubbo and for $195 he could get

it in from Mudgee” (Interviewee 5 2013, pers.comm., 25 August).

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2001 2006 2011

Total Family Income for Wellington Council per

Household (Weekly)

Less than $799 $800 - $1,499 $1,500 - $2,499 More than $2,500

34

According to a survey of Australian residents by SBS News, 42% of people who were surveyed

agreed that, “The mining boom has driven up the cost of living”, while only 8% disagreed (SBS

2012). Even though those surveyed by SBS are a sample of the general Australian population,

it does represent a common sentiment of those living in settlements effected by mines and their

economic impact.

The effect that the coal mines have had on the various industry sectors in the Mid-Western

region which has led to a higher cost of living is given in the Wilpinjong Coal Project

Environmental Assessment Report prepared by Gillespie Economics (2005, Appendix I). The

report estimated that there would be $244M in annual direct and indirect regional output or

business turnover; $158M in annual direct and indirect regional value added; and 14M in

annual household income. This is a substantial injection of cash into the regional economy that

can benefit a number of different sectors throughout the regional economy.

The report detailed the most probable flow-on impacts on the regional economy from the

construction and operation phases of the Wilpinjong Coal Mine. These flow-on impacts are

transferable between the different coal mines in the region due to the similar principle nature

of their construction and operation. The sectors most impacted by the Wilpinjong Coal Mine

are likely to be cement manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, road transport and

accommodation (Gillespie Economics 2005: 16). Gillespie Economics breakdown of which

sectors would be impacted on during the construction and operation phase is given below:

“Production-induced employment impacts during the construction

phase would mainly generate demand for employment in the:

services sectors (predominantly other property services, legal,

accounting and business management sector, scientific research,

technical and computer services and other business services);

wholesale and retail trade;

manufacturing (predominantly cement lime and concrete slurry

manufacturing, structural metal products manufacturing and

fabricated metal products manufacturing); and

transport sector (predominantly road transport…

35

Consumption-induced employment flow-ons from the construction

phase would mainly generate demand in the:

wholesale and retail trade sectors; and the

services sectors (education, health, community services and other

services” (Gillespie Economics 2005: 17).

“The sectors most impacted by output, value-added and income flow-

ons during the mine operation phase are likely to be the:

services to mining sector which consists of businesses engaged in, among

other things, exploration or parts of mining operations on a fee or contract

basis;

agricultural and mining machinery manufacturing sector which consists

of businesses engaged in, among other things, construction, earthmoving

and mining machinery;

electricity supply sector which consists of businesses engaged in the

generation, transmission or distribution of electricity;

wholesale trade sector which consists of businesses engaged in wholesale

trade;

retail trade sector which consists of business engaged in retail trade;

rail and road transport sectors which consists of businesses engaged in

operating railways for the transportation of freight or passengers and

businesses engaged in, among other things, the transportation of freight

by road;

other property services sector which includes business involved in renting

and leasing assets including machinery, equipment, motor vehicles, real

estate, airplanes, etc; and

legal, accounting, marketing and business management services sector

which includes businesses that provide legal services, accounting services

or business management services including environmental consultancy

services and personnel management services” (Gillespie Economics 2005:

23).

36

However, as the report concludes, there are limitations to the number of locals that are able to

be employed in the coal mines due to the specialist nature of the skills and education required

for coal mining and associated services (Gillespie Economics 2005: 21). Also, the fact that the

report lists a number of services which could be sourced locally, increasing employment in the

region, should be viewed with some scepticism. The reality of large multi-national corporations,

which own and operate the mines using, for example legal, accounting and marketing services,

sourced from within the Mid-Western region is highly unlikely given the large amounts of

money involved.

Gillespie Economics estimated that around 50% (around 250 direct and indirect jobs) could be

sourced locally in the region, with the remainder coming from workers who will need to migrate

into the region (2005: 21). However, as Interviewee 5 stated, the mines tried to locally source

as many of its workers as possible. “…we would have no problem with a locally sourced labour

force to work in the mines. Which is what we set out to do” (Interviewee 5 2013, pers.comm.,

25 August).

While there may be large capital investments during the construction and operation phases of

the coal mines in the Mid-Western region, the cessation of operations for the mines, if handled

poorly, can result in large economic and social problems. The scale of the regional economic

impact during this running down and cessation phase of the coal mines would most likely

depend on whether the mine workers and associated workers and their families would leave

the region. According to the Wilderness Society who commissioned The Economic Impact of

the Woodchipping Industry in South Eastern NSW, where workers who had been displaced in

the region remained, the consumption-induced flow-ons of the decline could ultimately be

reduced through the sustained consumption expenditure of those who remained in the region

(Economic and Planning Impact Consultants 1989). The decision by workers to remain or

move at the running down and cessation of the coal mine would be affected by the prospects

of gaining other employment with similar wages in the region compared with other regions,

the likely gain or loss associated with homeowners selling, and the quality of lifestyle in the

region (Economic and Planning Impact Consultants 1989).

However, as mentioned above, due to the specialised skills and education requirements needed

for working in coal mines it would be difficult to accurately determine the number of coal

workers that would remain in the Mid-Western region after the closure of the mines due to

limitations in finding similar work. Ultimately, if the running down and cessation of the coal

37

mines happens during a period when the region is experiencing growth in a diversified

economy, which has other development opportunities, the impact on the economy and

employment would be less (Sorensen 1990). Conversely, if the region becomes too reliant on

the coal mining industry, then mine closures could result in direct job retrenchment for locals

and indirect job losses as a result of businesses which rely on services to the mine’s employees

(Rocha and Bristow 1997: 15). Presently this does not seem likely to occur due to the strong

agriculture, viticulture and tourism industry in the region which is independent of the mines.

While the overall impact on the economy and employment caused by the coal mines in the

Mid-Western region has had positive and negative consequences, the changing economy and

demographics of the region has also impacted on health services. The health services in and

around Mudgee have been placed under increased pressure during the construction and

operational phases of coal mine developments. This has caused workers and their families to

migrate to the region to work for the coal mining industry, leading to a 3.1% increase in the

population in Mudgee and 2% increase in the overall population of the MWRC between 2011

and 2012, compared to 1.1% in the rest of NSW (ABS 2013).

Mudgee Hospital is the largest health facility in the MWRC, offering medical services

including Gastroenterology, General Medicine, General Surgery, Infectious Diseases, Kidney,

Medicine, Maternity, Neurology, and Ophthalmology. According to the My Hospital website,

Mudgee Hospital has less than 50 beds and experienced a total of 3,258 admissions during the

2011 – 2012 period (Commonwealth of Australia 2013b). Since the permanent closure of the

Gulgong Hospital in 2010 due to asbestos being found, Mudgee Hospital has become the only

health facility for nearly 4,000 people in Gulgong and the surrounding townships, who must

now travel further to receive medical treatment and care (Keene 2010). According to the 2011

– 2012 NSW Health Budget, $7M has been put towards the construction of a multi-purpose

health facility at Gulgong, to be completed in 2014. (NSW Government 2013: 8). This new