February 1973 (26th year) - U.K. : 13p - North America:...

Transcript of February 1973 (26th year) - U.K. : 13p - North America:...

TheA window open on the world

February 1973 (26th year) - U.K. : 13p - North America: 50 cts - Franca: 1.70 F

Photo © from " Bellas Artes ", N» 17, 1972, Madrid, (" La Dama de Baza " by F. J. Presedo)

TREASURES

OF

WORLD ART

fö SPAIN1 FEV. 1973

Lady of Baza

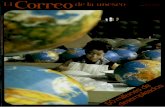

Dating back some 2,400 years, this statue (detail of a figure seated on a winged throne)was unearthed from an ancient burial ground at Baza (hence its name "Lady of Baza")in Granada (Spain), and may have served as a funerary urn. Spanish archaeologists haveuncovered striking pieces of Iberian monumental carving with a distinctive " oriental "style, including statues of priestesses, the famous " Lady of Elche ", found on a site120 miles from Baza (see " Unesco Courier", December 1970) sphinxes, lions, bulls andhorsemen. The statue is now in the Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid.

CourierFEBRUARY 1973

26TH YEAR

PUBLISHED IIM 14 LANGUAGES

EnglishFrench

SpanishRussian

German

Arabic

Japanese

Italian

Hindi

Tamil

Hebrew

Persian

Dutch

Portuguese

Published monthly by UNESCO

The United Nations

Educational, Scientific

and Cultural Organization

Sales and Distribution Offices

Unesco, Place de Fontenoy, 75700 Paris

Annual subscription rates £ 1.30 stg.; $5.00(North America); 17 French francs orequivalent; 2 years : £ 2.30 stg. ; 30 F. Singlecopies: 13 p stg.; 50 cents: 1.70 F.

Tha UNESCO COURIER is published monthly, except inAugust and September when it is bi-monthly (11 issues ayear) in English, French, Spanish, Russian, German, Arabic,Japanese, Italian, Hindi, Tamil, Hebrew, Persian, Dutch andPortuguese. For list of distributors see inside back cover.

Individual articles and photographs not copyrighted maybe reprinted providing the credit line reads "Reprinted fromthe UNESCO COURIER," plus date of issue, and threevoucher copies are sent to the editor. Signed articles re¬printed must bear author's name. Non-copyright photoswill be supplied on request. Unsolicited manuscripts cannotbe returned unless accompanied by an international replycoupon covering postage. Signed articles express theopinions of the authors and do not necessarily representthe opinions of UNESCO or those of the editors of theUNESCO COURIER.

The Unesco Courier is indexed monthly in theReaders' Guide to Periodical Literature, published byH. W. Wilson Co., New York, and in Current Con¬tents Education, Philadelphia, U.S.A.

Editorial Office

Unesco, Place de Fontenoy, 75700 Paris - France

Editor-in-Chief

Sandy Koffler

Assistant Editor-in-ChiefRené Caloz

Assistant to the Editor-in-ChiefOlga Rodel

French

SpanishRussian

German

Arabic

Edition

Edition

Edition

Managing EditorsEnglish Edition : Ronald Fenton (Paris)

Edition : Jane Albert Hesse (Paris)Edition : Francisco Fernández-Santos (Paris)

Georgi Stetsenko (Paris)Hans Rieben (Berne) tAbdel Moneim El Sawi (Cairo)Kazuo Akao (Tokyo)Maria Remiddi (Rome)Kartar Singh Duggal (Delhi)N.D. Sundaravadivelu (Madras)Alexander Peli (Jerusalem)Fereydoun Ardalan (Teheran)Paul Morren (Antwerp)

Benedicto Silva (Rio de Janeiro)

Japanese EditionItalian

Hindi

Tamil

Hebrew

Persian

Dutch

Edition

Edition

Edition

Edition

Edition

Edition

Portuguese Edition

11

16

21

_

22

24

28

30

33

34

SCIENCE AND MYTH

By Pierre Auger

SCIENCE IS GOOD FOR YOU

By Dan Behrman

THE ENIGMA OF THE THRACIANS

By Magdalina Stancheva

INTERNATIONAL PROBLEMSOF TELEVISION VIA SATELLITE

A major debate at Unesco's General Conference

By Gunnar Naesselund

UNESCO DECLARATIONON SATELLITE BROADCASTING

AFRICA IN THE STRESS OF TECHNOLOGY

By Ali Lankoandé

AMERICANS READ MORE BOOKSTHAN EUROPEANS

A German specialist looks at reading habits on two continents

By Heinz Steinberg

LATEST PROFILE OF WORLD TRANSLATIONS

Facts from Unesco's " Index Translationum "

UNESCO NEWSROOM

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

TREASURES OF WORLD ART

Lady of Baza (Spain)

Assistant Editors

English Edition : Howard BrabynFrench Edition : Philippe OuannèsSpanish Edition : Jorge Enrique Adoum

Illustrations : Anne-Marie MaillardResearch : Zoé Allix

Layout and Design : Robert JacqueminAll correspondence should be addressed to

the Editor-in-Chief

SCIENCE AND MYTH

In science fiction we can accept the

fantastic and extraordinary because we

know they are not true. But in recent

years there has been so much talk in

the press, on TV. and elsewhere of

robots that "think", computers that have

"nervous breakdowns" or "flying sau¬

cers" manned by creatures from outer

space that such myths are being taken

for scientific fact Science populariza¬

tion today therefore has an important

role to play toward a better under¬

standing of science as distinct from

the myths.

SCIENCE AND MYTH

byPierre Auger

Talk of machines that "think", computershaving "nervous breakdowns" "flyingsaucers" is creating a new kind of mythhiding behind the cloak of science.Here a leading French scientist discussesmodern myths in relation to a trueunderstanding and popularization of science.

_ O the sensational progressof science and of physics and biologyIn particular what Is generally calledthe general public reacts in threedifferent ways.

Some admire and even wax enthus¬

iastic about the daring exploits ofastro-physics and molecular biology.Without being really able to add totheir own knowledge, they sense thegrandeur of this amazing adventureof the human mind.

Others are struck, above all, by thetechnical achievements which follow

in the wake of scientific progress, suchas communications satellites, super¬sonic flight, and exploration of themoon and of the ocean floor. The

power of man equals, and in certainfields surpasses, that of the gods ofantiquity.

There ¡s a third attitude, however,which is wholly compounded of theanxiety and distrust inspired byscientific progress and at the sametime perhaps even primarily by theattendant technical progress. Whereare we heading with these machinesand computers? Can we be sure thatthese atomic, space and geneticadventures are not going to end indisaster?

Thus, if the writer on scientific sub¬

jects is to cater for every category ofreader, he must not take the easypath and be content with tending andfeeding the sacred fire of the firstgroup we have described, and withproviding fresh grounds for the enthus¬iasm of the second group. He musttake care to reassure the third group,

4

PIERRE AUGER, is a leading French physicistand former Director-General of the EuropeanSpace Research Organization (ESRO) whichhe helped to set up. He was head ofUnesco's Department of Natural Sciencesfrom 1948 to 1959 and is the author of"Current Trends in Scientific Research", acomprehensive survey of world scientific andtechnological research published by Unescoin 1961, 3rd edition 1963 (see also articlepage 1 1).

and this he must do by re-establishingthe truth, not the truth pure and simple,for the truth is complex and oftenabstract, but the naked truth bywhich I mean stripped of the fantastictrappings with which it is all too oftenembellished by publicists I dare notcall them writers who are either naiveand ill-informed themselves or else

unscrupulous popularity-hunters.

There is no denying that this is avery difficult task. It is even regardedas an impossible one by some peopleof sound judgement who see theattempts of science writers to acquaintthe general public with certain fieldsof knowledge as leading simply to thecreation of a new kind of mythology.

I can be quite frank here and admitthat they are often right. This is certainlyone of the main rocks on which the

efforts of those known as popularscience writers come to grief. It is arock never struck by the writers ofthose works of fiction in scientific garbwhich fill library-shelves labelled"science-fiction". Here, the creationof myths is the avowed aim.

A word of warning however. It isessential that the mythical nature ofsuch books be clearly indicated sothat there is no mistake about whatis being offered for public consumption.There has been too much talk of

machines that think, computers thatget nervous breakdowns and flyingsaucers with little green men fromouter space. From all this thereseems to have been born a kind of

myth which people, are beginning totake as scientific fact.

But let us look at what the popularscience writer can do to communicate

knowledge instead of new myths. Firstof all, what distinguishes a scientifictheory from a myth?

Here I am using the word myth tosignify an explanation or theory ofnatural or human phenomena andevents, like those handed down bytradition in ancient times and those

still transmitted in this way by so-called

uncivilized peoples following thethought processes of "the savagemind" described by Claude Lévi-Strauss.

These myths make use of figureswith human characteristics and animals

gifted with supernatural powers, butthey also present abstract forces suchas Fate or mana, particularly thosesecreted in certain objects.

The expression "scientific theory"is also used to signify explanations ofnatural and, if need be, humanphenomena, and although these explan¬ations do not make use of human

figures or animals, they neverthelessattribute specific properties to certainobjects which secrete forces and arecapable of generating phenomena andbringing about events.

Examples of such objects aremagnetized or electrically chargedbodies, and radioactive or fissile subs¬

tances. The analogy is so strong asto cause confusion in some cases and

myths then grow up around machines,magnets, high-tension cables andships. A good example is the cargo-cult that grew up around the steamersbringing wealth to the islands of thePacific.

I shall be told that the educated

public of the developed countries willnot fall a prey to such confusion. Butit is precisely on this point that I wouldbe tempted to share if only verypartially the pessimistic opinion Imentioned earlier.

Are we quite sure, in fact, that theinformation given by the popularscience writers is always properlyunderstood in the scientific sense?

Is there not a tendency among thegeneral public, or a large section ofit, simply to trust the presumablycompetent dispensers of informationand to be content with metaphors andrather vague analogies.

To give an example, it is said quitecommonly that space engineers havemanaged to put a satellite in orbit, or

CONTINUED PAGE 6

These soaring spires and towering skyscrapers are not part of a mythical lunar landscape, but anomalous crystalsof a lead, tin, telluride alloy, about 2 millimetres high, as seen by a stereoscan microscope. These and similar crystalsare used in infra-red lasers and experiments are being made on their use in earth-satellite, satellite-satellite spacecommunication (see also story on Unesco and communications satellites page 21) as well as in blind landing systemsfor airports.

5

The legend of the magnetic mountain Magnetism was such a mysterious phenomenon that It gaverise to a whole mythology among the Ancients. Thegeographer Ptolemy wrote that, near present-day Borneo,there existed mountains "of such great powers of attractionthat ships are built with wooden pegs, lest the iron nailsshould be drawn from the timbers" with disastrous results

(left). The legend of the magnetic mountain was repeated In"A Thousand and One Nights" and was accepted as trueuntil early In the 17th century when men such as WilliamGilbert, "the Galileo of magnetism", laid the foundations ofmodern theories. Below, the lines of force in a magneticfield as drawn by James Clerk Maxwell In 1865. Iron filingsattracted by a magnet (right) form patterns which enable usto "see" the magnetic field. Curious patterns can be builtup in this way in photo right one can imagine the head ofan otter or a beaver and some contemporary artists makeuse of the properties of magnets in works of kinetic art.

6

SCIENCE AND MYTH (Continued)

that it has gone off its trajectory andfallen into the sea. In this case, itseems clear that the orbit and the

trajectory are thought of as abstractobjects which the satellite may followor leave just as a train does the track,or a car the road. This is under¬

standable since we model our con¬

ceptions on familiar facts and events.

Unfortunately, the model in this caseis a bad one and leads to false ideas

about space mechanics. It is perhapsappropriate to use the term myth, inthis instance, by comparison withthose myths about the planets or thesun in which the heavenly bodyfollowed real paths laid down by thegods.

We have another example in radio¬activity and radium. A veritable mythhad grown up around these glamorouswords, and every mineral water andeven some beauty creams used toboast of being radioactive, for this wasa guarantee of efficacy. We haverecently witnessed a spectacularreversal of the myth, since radioactivityis now considered dangerous becauseof fallout and the labels on the

mineral water bottles and jars ofbeauty cream have been surreptitiouslybrought up to date.

What has to be done, people willsay, is to give more detailed informa¬tion, explain the laws of celestialmechanics, and throw light on the realnature of radioactivity, striking thebalance between its benefits, as in thetreatment of cancer, and its dangers.They are right of course, and this iswhat many serious popular sciencewriters are doing, backing up the veryeffective and, it must be said, evenessential efforts being made at alllevels of the education system.

Only piecemeal improvements willbe made in this way, however, whenthe subjects being dealt with areparticularly in the news. A moregeneral strategy must be adopted ifwe are not to rest content with small

tactical victories.

In this connexion, I would like tomake a suggestion based on theconcept of a "model". A model, whichis basically nothing more than theconcrete representation of an abstracttheory, is a tool for thought and evenfor discovery which is very usefulboth in making scientific progress andin giving an account of such progress,scientists being no different from othermen in the way they think. To makemyself clearr I shall draw a parallel

' *. . ,'*

Photo Bibliothèque de Genève

between myths and models, and firstof all, I shall recall a few facts fromthe history of science.

Scientists usually take pride inpresenting their results In the mostperfect and most elegant form, withoutgiving any idea of the gropings, thefalse starts, and the hard intellectual

and experimental work which led upto them.

It is understandable that they shouldwish not to overburden their writingwith details which have ceased to beof current interest. On the other hand,how worthwhile it would be to followstep-by-step the thought and thelabour of this or that great discovererin his exploration of new scientificfields.

In the few cases where this hasbeen possible thanks to an auto¬biography or a series of publishedpapers, it has made an exciting andinstructive study. We can see thepart played by models and preliminaryplans which are like scaffolding to beremoved when the building has beencompleted.

These models are often concreteones, sometimes visualized as im¬provised mechanisms. This was so

i

i * i

&

Photo © Le Cuzlat, Levallols, France

in the case of James Clerk Maxwell,

for example, who had experimentedwith models of rollers centred on the

lines of magnetic force and represent¬ing the movements of electricity.Once his equations had been estab¬lished, all the apparatus was discardedand the equations are now elegant,perfect and abstract. They arealso completely incomprehensible toanyone who has not undergone alengthy initiation.

Many models remain very useful,however, even when the knowledgethey represent has been outdated bymore general theories. Bohr's planet¬ary model of the atom, for example,still serves quite adequately to inter¬pret many properties of the atom andthe molecule. It has the further

advantage of being sufficiently visualto be easily accepted by non-specialists.

The even older model of the elastic

atoms of the kinetic theory of gasescontinues to be employed. A greatEnglish scientist admitted that he stillused it to help him think out his ideas."When I think of the thermic agitationof the atoms of a gas", he said, "Icannot help seeing little red and white

balls knocking against each other."Of course he knew very well that themodel was inadequate.

This is the heart of the matter and

one of the big differences betweenmodels and myths. The model ispartial, incomplete and provisional,constructed to be useful for a time

(sometimes a very long time!) and thensuperseded. The myth, on the otherhand, is total and definitive from theoutset and in this draws close to belief.

We shall find other characteristics

which carry it at the same time fartheraway from scientific theory.

But do not theories themselves run

the risk of changing into myths if theyare treated too much as if they wereabsolutes? We have the old exampleof phlogiston which gave metals theirsheen and hardness and which

resisted the theory of oxidation sostubbornly.

Are we not also justified in sayingthat absolute time has become a mythstill perpetuated by many educatedpeople although it is nothing morethan a model which is very adequateon most occasions but must yield tothe four-dimensional universe of

Minkowski and Einstein.

There is an obvious defence againstmyths: it is built into the scientificmethod itself which considers theories

good as long as they account forphenomena in the best possible wayand especially when they represent aminimum number of arbitrary rules andparameters for a maximum number offacts explained. In the realm of myths,on the other hand, there is one mythfor each fact or occurrence to be

explained, just as the ancient Romanshad a different god for each of life'sevents, no matter how insignificant.

Here we come to the most sensitive

point the one which Is the chiefworry, not to say nightmare, of themodern lovers of myth the touchstoneof experiment. A theory, however fineit may be, gives way when confrontedwith a contradictory fact establishedby experiment. A myth does not giveway but argues, evades and findsoften purely verbal loopholes.

This is true of the myth of the waveswhich are emitted by thinking mindsthe thought waves in telepathy thefluids or waves operative in water-divining, "second sight", extra-sensoryperception, and so on. Experimentaldemonstrations to the contrary have

CONTINUED NEXT PAGE

7

SCIENCE AND MYTH (Continued)

8

no effect on myths and this is anexcellent way of distinguishing them.

This is not to say that theoriesmust be immediately confirmed byexperiment if they are to be consider¬ed scientifically respectable. Experi¬mental confirmation might not comefor some time. Researchers will

devote all the more effort to this task

if the theory has internal logic, islinked with other scientific fields, andsynthesizes numerous facts alreadyknown, all these being the character¬istics of a good theory.

One example is Pauli's hypothesisof the existence of the neutrino, aparticle having no mass, no magneticfield, no electric charge and hardlyany effect in its passage throughmatter but which made it possible torestore to their place under the generallaws of the conservation of energy andthe quantity of movement, absolutelysure experiments lying apparentlyoutside their scope.

"The neutrino is a myth", said somephysicists. Experiments have never¬theless shown that it exists, and itplays a fundamental role in nuclearphysics. Two or three other hypo¬theses of this kind are currently beingtested, namely the quark, the partonand the intermediate boson. Theyare good hypotheses which areawaiting the verdict of experiments.They are not myths.

If we wish to explain this to a widepublic which is so often impressed bythe romantic aspect of the myths wespoke about earlier, and also of themyths concerned with vitalism, vitalforce and vital impulse, we must laystress on the quantitative, measurableand calculable aspects of correcttheories, as opposed to the resolutelyand purely qualitative character ofmyths.

The rotational force of spiritualists'turning tables has never been mea¬sured nor the speed of propagation oftelepathic waves and for very goodreasons. Calculations of the neutri¬

no's precise energy and velocity (thatof light) were made even before it wasfound and they proved to be correct.

The case of the neutrino is obvi¬

ously a perfect example. There is noreason, however, why the seriouspopular science writer should penalizehimself by disregarding the fact thatall classes of readers are attracted

by accounts sometimes full of theunexpected and even of a kind ofromanticism of the great scientificdiscoveries and movements, of theopening up of the great avenues ofscience.

Several books could be quotedwhich tell of adventures in connexion

with the life of a scientist or the

development of a school or laboratory,and which are full of memorable

anecdotes, some of which have agenuine scientific interest since thereal life situations they describe showhow scientific thought develops.

What a lot there is to learn from

books like these, either for youngpeople attracted towards science oreven for the general reader seekinga better understanding not only of thefindings of research but also of "howit was done" and how such discov¬

eries are made.

Books like these bring out the rôleof scientific information, in otherwords, of knowledge of what hasalready been done, the rôle of theimagination which makes it possibleto get out of the rut and discovernew paths, and the rôle of chanceor of luck, as some would say arôle which has often been grosslyexaggerated by sensation-mongeringcommentators, and "forgotten" bythose who have benefited from it.

They are wrong, anyway, for thereis nothing more superbly human thanthe power of the mind to launch a newtrain of thought from facts or remarkswhich will be overlooked by peoplewho are incapable of wonder. Theclassic examples are Henri Becque-rel's discovery of radioactivity, theresult of choosing a uranium oxide saltas a fluorescent substance, and Don¬ald Glaser's bubble chamber inspiredby a glass of beer.

The "personalized" history of scien¬ce can also be a way of admitting thegeneral public into the laboratory andshowing the amount of work, thought,experimental skill and, finally, patience

ZEUS,

BY JOVE!

Left, Zeus, or Jupiter orJove, thunderbolt in hand, asdepicted on a 5th centuryB.C. Greek amphora. TheGreeks and other ancient

peoples believed that the"god of gods" expressed hisanger with men by hurlingthunderbolts down on earth.

It was not until the time of

Benjamin Franklin (and hisRussian contemporary MikhailLomonosov) that this naturalphenomenon was linked withthe new discoveries beingmade about electricity. In1752, Franklin conducted hisfamous experiment of flyinga home-made kite in a thun¬

derstorm (right) to prove thatlightning is electricity, whichwas to lead him to invent the

lightning conductor or rod.Far right, an artist's none tooserious impression of a possi¬ble application of the newinvention, drawn In 1778.

The world's first journal devoted to thepopularization of science was the "Scien¬tific American" which began publication innewspaper format in August 1845 and lateradopted magazine format. Gerard Piel, itspresent publisher, was awarded the UnescoKalinga Prize for the Popularization ofScience in 1962.

>

ïto

Z

fPÊHcuras»

MC

m=. ge«

that underlies great discoveries andbreakthroughs. Pasteur defined geniusas endless patience and Newton saidthat he had discovered the law of

gravity by thinking about it.

I believe that a great effort must bemade to bring people who have neverbeen inside a research institute to

appreciate the true value of the workdone by all those research workerswhose names will never get Into theheadlines but who make a vitallyimportant contribution to scientific pro¬gress.

The danger of presenting the dailylife of research workers in this wayparticularly on television lies perhapsin the contrast with the descriptionsgiven in science fiction, which, need¬less to say, depict only dramaticsituations.

There is a risk of taking the poetryout of science or at least out of

research thus serving the cause ofthose who place in opposition thefamous "two cultures" of Lord Snow

(1). To my mind, the remedy lies inthe fullest possible integration of allthe activities of the human mind and,

I should like to add, good taste andsensitivity.

(I) In his book "The Two Cultures", LordSnow compares humanistic and scientificcultures through interviews with engineers,scientists and men of letters which he uses

to show the cleavage between them.

Who is going to write the "Worksand Days" of the scientific researchworker? Possibly this is asking toomuch, but it is certainly worthwhile todescribe the aspects of science'scurrent values which have a highintellectual and even artistic quality.

One of the characteristics of Scien¬

ce with a capital S which hasbecome more and more obvious over

the last fifty years is its unity. Thegeneral public must realize that inscience there no longer exists a juxta¬position of subjects classified accord¬ing to the order introduced by AugusteComte or following a less strictlylinear order, but instead an immensenetwork of facts and theories forminga pattern from which there emergesthe outline of a veritable structure

encompassing the whole of nature,from the universe to living beings.

This structure cannot be understood

unless it is analysed down to thecomponents of matter and energy, forit is at the level of atoms and mol¬

ecules that physics, chemistry andbiology meet. We must penetrate asfar as the nucleus of the atom andits constituent elements in order to

add astronomy and cosmology to theother sciences.

Mathematics, of course, are every¬where and our world is indeed the one

which Pythagoras had imagined. "All

things are numbers", he said, but whatwould he have thought of the vastfield now covered by numbers?

Beginning with the simplest, thereis the number 2, following unity andintroducing diversity; it might be saidto be the atom of diversity from whichit is possible to build up the mostextreme complexities, just as all thematter of the universe can be derived

from the hydrogen atom and the neu¬tron.

Then there are the quantum numberswhich are small integral numbersorhalf-integral or even third-integral num¬bers, at the extreme limit while at theother end of the scale of complexities,the chains of macromolecules of

chromosomes offer possibilities ofcombinations numbering thousands ofmillions. Here, too, the structure issimple, however, because we needonly four symbols to write the greatbook of the anatomy and physiologyof Manl Mathematicians will say thattwo would be enough, but the chainswould then be much longer andperhaps too long to remain stable.

Here, then, are two of the greatideas which are shaping the futuredevelopment of science: the questfor a structural unity which is nolonger just an intellectual need but isgradually becoming discernible anddefinable and the quest for a complex¬ity which underlies the extreme variety

CONTINUED NEXT PAGE

9

Photo Erich Lessing © Magnum, Paris

THE TIME-SPACE

CLOCK

Einstein's theory of relativity completely changed man's notions of space and time. Einsteinhimself wrote, "There are only local times. On earth, for example, everyone is catapultedthrough space at the same velocity the velocity of the earth. Thus all the clocks on earthrun on equally, and record "earth" time. For a body In motion like the earth, this Is itsown time... Now when two events take place far away from each other spatially, enormousperiods of time are involved. It is no longer possible to say which event took place firstand which second. Depending on the velocity of the observer vis-à-vis the event, eitheranswer might be made; and either would be true for a given case."

10

SCIENCE AND MYTH (Continued)

of beings (or objects) and phenomenain the universe.

The first trend has often been called

reductionism, and it cannot be deniedthat it has been dazzlingly successful,although, it has not led to the discoveryof unity in some areas of research,even when followed by geniuses likeEinstein. There are still four forces

which cannot be expressed in termsof each other and these are the StrongNuclear force, the Weak Interaction,Electromagnetism and the Force ofGravitation. Nevertheless fresh hopesare raised every day.

The second line of research has

recently been extremely successful inthe field of biology with genetics andmolecular biology, and is gainingground each day. It holds out thehope that we may come to understandthe mechanisms of cellular differentia¬

tion, immunity, and perhaps cancer.

The small and, especially, the verybig molecules forming the links of thechains of these systems of reaction,catalysis, energy exchange, electronsand protons, are more and more fre¬quently the subject of scientific trea

tises and articles. They represent aworld which is enclosed within the

living world but Is generally imper¬ceptible.

In fact, until the end of the lastcentury it was virtually only in hand¬ling plants that this arsenal of complexand active substances, which compos¬ed the pharmacopoeia of antiquity andwere also the preserve of the cook,dyer and perfumer, had been recog¬nized and used. Today, as well asthese essences and alkaloids, there is

a growing list of the proteins compris¬ing the various enzymes and co¬enzymes found in this protoplasmwhich used to be compared to a dropof egg-white!

To bring the non-scientific public toappreciate the value of such researchwork, we must, of course, highlightthe two characteristics of science:

knowledge and utility. There must bea better understanding of the worldaround us, and thus a link-up with theintellectual mission of humanism. Peo¬

ple must also learn how this know¬ledge -is used in technical applicationsand 'inventions calculated to improve

man's lot, so that science is seen inits social rôle. This rôle is not a

straightforward one, as the currentproblems of industrialization show, butknowledge ¡s a prerequisite.

This brings us back to the originof the three attitudes which we

mentioned at the beginning: the beau¬ty, utility and dangers of science. Wehave to sail a stormy sea, guided bythe stars, taking advantage of favour¬able currents and avoiding reefs.

This is possible only if the crews,ratings as well as captains, retainconfidence in themselves, their reason

and their vigilance and, like latter-dayUlysses, allow themselves to be ledastray neither by the siren voices ofall the mythologies nor by the riskof avoiding the Charybdis of Herme-tism and the ivory tower only tofounder on the Scylla of defoliationsand nuclear explosions.

I am not a believer in the religioussense of the word, but I neverthelessthink, like the Church, that the greatestsin is despair, and for Man to despairof science and knowledge would be todespair of himself. '

SCIENCE

IS

GOOD FOR YOU

An interview with three

Unesco science prize winners

by Dan Behrman I

DAN BEHRMAN is a Unesco science writer.

He is the author of "The New World of the

Oceans" (Little Brown and Co., Boston,U.S.A.) also published in a paperback edition,and "In Partnership with Nature: Unesco andthe Environment" , Unesco, Pans, 1972.

b^m3 '«S r/1*-

T has become fashionable

to decry science or, at least, thoseunfortunate aberrations of technologythat masquerade as science. From his

rôle as a latter-day folk hero, thescientist has been transformed bysome into a scapegoat for all ourpresent ills.

Funds no longer flow his way withno questions asked, students in manyplaces turn their backs on his calling.Even industrial polluters, like drunk¬ards who promise to take the pledge,

1 1 I I

1 \^ ^S

i^B ^H

Vaio

ce

<D

O"

C

Eo

û

ooCO

«c

D

ta

o

o.c

a.

Left, Prof. Pierre Auger (France) winner of the 1971 Kalinga Prizefor the Popularization of Science. The Unesco Science Prizefor 1972 was awarded jointly to Dr. Viktor Kovda (U.S.S.R.)centre, for his research on the "salting" of soil and the use ofbrackish water for irrigation, and to nine Austrian scientists andengineers, represented by Wolfgang Kühnelt (right) for theirdevelopment of a new and cheaper way to make steel (theLD process). "*

are in the front ranks of those who

call for a*return to the paradise that issupposed to have existed before theEcological Fall.

In this often-justified furore overwhat science and technology havedone to us, we tend to forget whatthe scientist is doing for us. And hehad better go on doing it. It is only aprivileged minority that can pretend toshunt him aside. The rest of the world

needs him more than ever. Wherever

men suffer from a lack of the essen¬

tials rather than a surfeit of the super¬fluous, science and its applicationshave an honourable part to play inhuman affairs.

Such was the tone of a rather un¬

usual ceremony held In November lastyear in Paris. Shortly after the closeof the 17th Session of the Unesco

General Conference, two prizes wereawarded by Mr. René Maheu, Unesco'sDirector-General, in one of the hallsthat had just been vacated by the con¬ference delegates.

On the rostrum were the three awardwinners, an Austrian, a Soviet citizen,

and a Frenchman respectively amaker of steel, an explorer of theearth's soils, and a nuclear physicistturned popularizer.

Varied though their backgrounds,origins and interests may appear, they 1 1had much in common. They were men * *

CONTINUED NEXT PAGE

SCIENCE IS GOOD FOR YOU (Continued)

with long careers behind them andthey shared an optimistic view of thefunctions and the future of science.

Dr. Viktor Kovda, corresponding mem¬ber of the Academy of Sciences of theU.S.S.R., and Mr. Wolfgang Kühneltfrom Austria divided the Unesco

Science Prize, each receiving $2,000.At the same ceremony, Dr. PierreAuger was given the Kalinga Prize forthe Popularization of Science, amount¬ing to 1,000 pounds sterling.

The Unesco Science Prize is award¬

ed every two years for achievementsof specific value to developing coun¬tries. In the past, it has gone to

scientists and engineers responsiblefor better ways of desalting water andgrowing food.

Mr. Kühnelt accepted his share ofthe prize in the name of the Austriangroup who developed the so-calledLD Steel Production Process, a new

and cheaper way to make steel, morethan twenty years ago. Others in thegroup cited by the award were Dr. Her¬bert Trenkler, Dr. Hubert Hauttmann,

Dr. Rudolf Rinesch, Mr. Fritz Klepp,Mr. Kurt Rösner, Mr. Otwin Cuscoleca,Mr. Felix Grohs and the late Dr. Theo¬

dor Suess.

Of the three prize winners at theUnesco ceremony, Mr. Kühnelt wasthe only representative of industry.Early in his professional life, he hadbeen an assistant lecturer in an Aus¬

trian university. But he preferred theaction of a steel mill to the groves ofAcademe, and now, on the verge ofretirement, he is deputy manager ofoperations of the Oesterreichisch-

Alpine Montangesellschaft plant at itsVienna headquarters.

Mr. Kühnelt recalled how, in 1949,

Austria was in somewhat the positionof a developing nation during thelean postwar years. Steel productionwas low, only a million tons a year,and it had to be raised.

But the country was short of scrapmetal, that essential ingredient in themanufacture of steel. Mr. Kühnelt and

his colleagues experimented with adifferent approach. Instead of blowingair through a molten bath of iron fromthe sides and below, they sent pureoxygen down onto the surface of theircrucible.

It wasn't a new idea to blow oxygeninstead of air. Sir Henry Bessemer,the English inventor and engineer hadpatented it a hundred years ago, butsteelmakers believed that the use of

pure oxygen would lead to brittlenessin steel.

The Austrians were not convinced;

they found a way to use the oxygen toget rid of the impurities in pig ironand, at the same time, keep it out ofthe steel. The method was developedat the plant at Donawitz and also at theVoest works at Linz, hence its name:

the LD process.

HE LD process wentaround the world. In 1952 and 1953,

the first LD plants opened in Austria;by 1954 the process was being usedin Canada. It was ideal for countries

with a small demand for steel. An

LD plant could be profitable producingonly 500,000 tons a year, as comparedto two million tons a year for traditionalprocesses. For once, technologicalprogress did not automatically implybigness.

Developing countries beat a pathto the Austrians" door. Steel men came

from India, Peru, Brazil and Tunisia to

learn the process, Austrians went totheir countries to teach it.

In Tunisia and Peru, the LD processhas been combined with continuous

casting: that is, the molten steelcomes out of the crucible and is cast

directly into slabs or billets instead of

12

20 winners of the Kalinga prize

1952 Prince Louis de Brogue (France) 1962 Gerard Piel (U.S.)

1953 Sir Julian Huxley (U.K.) 1963 Jagjit Singh (India)

1954 Waldemar Kaempffert (U.S.) 1964 Dr. Warren Weaver (U.S.)1955 Augusto Pi Suner (Venezuela) 1965 Dr. Eugene Rabinowitch (U.S.)

1956 Professor George Gamow (U.S.) 1966 Paul Couderc (France)1957 Lord Bertrand Russell (U.K.) 1967 Sir Fred Hoyle (U.K.)

1958 Dr. Karl von Frisch (Fed. Rep.of Germany)

1968 Sir Gavin de Beer (U.K.)

1959 Jean Rostand (France) 1969 Dr. Konrad Lorenz (Austria)

1960 Lord Ritchie Calder (U.K.) 1970 Dr. Margaret Mead (U.S.)

1961 Arthur C. Clarke (U.K.) 1971 Dr. Pierre Auger (France)

ingots. The advantage is considerablefrom the viewpoint of cost. Ingotsmust go through a blooming mill, slabsor billets are already in a more usableform. Small countries with small

budgets need to invest less money inrolling mills.

Speaking in the name of the Aus¬trian steel men who made their first

tests with a two-ton crucible (the big¬gest LD crucible now in use holds400 metric tons), Mr. Kühnelt let figuresdo most of the talking. Austrian steelproduction has gone up from one tofour million tons. In 1954, total world

steel production amounted to 223 mill¬ion tons; seventeen years later in1971, the LD process was accountingfor 250 million tons, or 41 per cent of

world steel output that year.

The LD process was born out ofeconomic necessity. Equally practicalconsiderations led to the research that

also brought the Unesco Science Prizeto Dr. Viktor Kovda. A former head

of the Science Department at Unesco,he is now director of the Institute of

Agrochemistry and Soil Science of theU.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences and heholds the chair of soil science at Lo-

monosov State University in Moscow.

Of particular relevance to the dev¬

eloping world has been in research onthe "salting" of soil through faulty irri¬gation methods and on ways to reclaimit while, at the same time, usingbrackish water for growing crops.

"R. Kovda too can recallhow his research started. In 1936 and

1937, he was carrying out field studieson Uzbehistan's biggest cotton farm,Pakhta Aral ("Cotton Island"), where10,000 hectares (25,000 acres) wereunder cultivation on the "HungrySteppe". At that time it was thoughtthat water containing more than onegramme of dissolved mineral salts perlitre (seawater has an average of 35grammes) was unsuitable for irrigation.

Dr. Kovda wanted to find optimal

conditions for growing high-qualitycotton. To his surprise, tests showedthat the best cotton was not producedwith water of low or no salinity. In¬stead, it flourished with a soil-watersolution of as much as 5 to 6 gram¬mes of salt per litre. Even when irri¬gated with water twice as brackish,the cotton could still survive.

In the Fergana Valley, that Dr. Kov¬da likes to refer to as the "paradise ofUzbekistan", the old farmers knew

they could irrigate with brackishwater. It meant growing salt-resis¬tant crops and irrigating more fre-

FISH

OR FOWL,

OR BOTH?

A shoal of fish imperceptibly becomes a flock of birds in this 1938 print by Maurits Cornelis Escher, aNetherlands engraver, whose drawings and prints have been widely reproduced in scientific books andarticles (See "Bookshelf, page 33). The design was used by Ivan Rosenqvist, a Norwegian geologist, todemonstrate the particular characteristics of two substances: clay and water. The centre line of the printrepresents the meeting point between particles of clay (birds) and molecules of water (fish). The further thebirds (clay particles) move upwards from the centre the more freely they fly. As the fish (water molecules)recede from the clay particles they too can move more easily.

quently on well-drained land so thatthe salts could be flushed out of the

soil. All this information was interest¬

ing but mainly academic because, inthose days, the U.S.S.R. had an ade¬quate supply of low-salinity riverwater.

Then, in 1957, Dr. Kovda was sentby his government as an expert tothe Arab Republic of Egypt. There, he

saw water as a truly scarce asset.Underground water with 5 to 7 gram¬mes of salt per litre usually consid¬ered a lethal dose for soil was beingused to irrigate oases that had remain¬ed productive for two or three millen¬nia.

The following year, he joined Unescoand visited Tunisia where the same

problem existed. Food had to be

grown but only brackish water wasavailable to grow it. With the sup¬port of President Habib Bourguiba ofTunisia, he proposed that an experi¬mental station be set up in the countryto test irrigation methods.

That was a decade ago. Today thework done in Tunisia under the United

Nations Development Programme hasshown how the great underground sea

CONTINUED NEXT PAGE

13

SCIENCE IS GOOD FOR YOU (Continued)

14

of brackish water lying below the aridlands of North Africa can be used to

support crops and trees where onlyrocks and sand existed before. The

lessons of Tunisia can be applied else¬where in the developing world.

Dr. Kovda has organized the prep¬aration by Unesco and the U.N. Foodand Agriculture Organization of an In¬ternational Source Book on Irrigation

and Drainage of Arid Lands ("Irriga¬tion, Drainage and Salinity", to appearshortly). He himself is the author ofsome 350 scientific works, includingten books and he is now active in

Unesco's Man and Biosphere pro¬

gramme.

Yet one might say that this all begansome fifty-odd years ago when a smallboy read the adventure stories ofJules Verne, Mayne Reid and JamesFenimore Cooper. Young Viktor Kov¬da wanted to be an explorer. He andhis brother built a boat and roamed

the rivers around their home just as

Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn didin the books of another of his fav¬

ourite authors, Mark Twain.

When he entered the University ofKrasnodar in 1927, it was a time of

scientific growth in his country. Hewas enamoured of science, but he

clung to his first love of exploration.Soil science allowed him to be true to

both. Even as a student he carried

out soil surveys in the field. His pro¬fessors had taught him the romance ofthe earth.

Almost fifty years later, the romanceIs still there. When Dr. Kovda accept¬ed the Unesco Science Prize, he spokeof our mother earth and how she can

punish us severely with drought,floods, earthquakes, volcanic erup¬tions. We dare not sit back and merelycontemplate nature, he said. "Only ifwe change nature with care will shebear fruit and we need not preserve

her virginity for future generations."

But mother earth is 5,000 million

years old, said Dr. Kovda, and shehas not had an easy life. We mustrejuvenate her. Twenty per cent of theearth's land surface is absolute des¬

ert and 40 per cent is arid or semi-

arid. If this land could be broughtinto production by irrigation, it wouldyield food... but not only food.

Photosynthesis would be takingplace over a vast area that is now

sterile. Plants would be using theenergy of sunlight to manufacturecarbohydrates, taking up carbondioxide in the process and releasingoxygen.

Dr. Kovda reminded his audience

that certain industrial areas alreadyshow an oxygen deficiency, produc

ing less than they consume. And weall know by now that the proportion ofcarbon dioxide in the earth's atmo¬

sphere is steadily rising as the resultof our holocaust of coal and oil, thefossil fuels. In other words, Dr. Kovda

has proposed that we organize acycling of oxygen and carbon dioxideby putting a plant cover over thedesert.

It is precisely the function of thescientist to think along such bold newlines when confronted by apparentlyinsoluble problems. Dr Kovda's hope¬ful assessment of the contribution that

science can make to the future of the

planet was shared, in the main, by thethird speaker on the rostrum at UnescoHouse.

At seventy-three, Dr. Pierre Augeris the oldest of the award winners,

but he is a remarkably young man inspirit. This is probably because hehas led a series of lives, first a twenty-year career in the laboratory as acosmic-ray physicist, then an almostequally long "life" as director ofhigher education in France after WorldWar II, head of science at Unesco, and

director-general of the European SpaceResearch Organization. And now, inan extremely active retirement, he iscontinuing his work as a popularizerof science, writing articles and makingradio broadcasts to answer the quest¬ions of a worried public.

Dr. Auger did not grow up in the

LANDSCAPING

FOR WATER

Right, massive earthmoving vehi¬cles line the bank of the futurecanal in southern Uzbekistan

(U.S.S.R.). When completed in 1975it will provide water to Irrigate avast area of arid land. In Uzbekis¬

tan, Dr. Viktor Kovda, winner ofUnesco's Science Prize, noted howfarmers used brackish water to irri¬

gate their land. Later, in southernTunisia, he proposed the use ofsimilar methods. Since then a U.N.

research programme has shown howthe great underground sea ofbrackish water below North Africa's

arid lands can be used to growcrops and trees a lesson that canbe applied elswhere in the develop¬ing world.

SPARKING A STEEL

REVOLUTION

For developing a revolutionary new pro¬cess of steel production a group of nineAustrian researchers was awarded the

Unesco Science Prize in November 1972.

Photo shows one phase of this productiontechnique the LD process in which pureoxygen is blown onto the surface of thecrucible. The LD process, a cheaper andmore efficient way to make steel, is nowused in all parts of the world.

1§mfe

l¿r^ ^~r ' '

4 «. -

i T

\V

1

i

4

1

1

, i1 -*

\ 1 . .

\

A « 1 i|Hr ^h¿

» till''t ¿TO, . Mi\J!ijWâKÉHI

-

*

Photo © APN, Moscow

countryside as young Victor Kovdahad done. His father was a professorof chemistry at the Sorbonne; hishome was steeped in science. TheAugers decided to give their son morethan an ordinary education in science.With several other Sorbonne scien¬

tists, they formed a "community" toteach science to each others' children.

Jacques Hadamard, a great Frenchmathematician, taught Pierre Augermathematics and geology. His fatherhad given him chemistry and his owninterests had led him to enter the

Ecole Normale In Paris as a biologystudent at the age of nineteen. There,he came under the influence of Jean

Perrin and his son. The elder Perrin

later won a Nobel Prize in physicswhile Francis, his son, became the

head of the atomic energy establish¬ment in France. Pierre Auger wasconverted to physics, but he alreadyhad an interdisciplinary view of thesciences that has never left him.

This made it all the easier for him

to project science beyond the bounds

of his profession and bring it within thegrasp of the general public. "Thepublic has a false idea of science", he

has said. "It sees dangers where none

exist; it does not see them where they

are really present. Atomic energy isfeared but it can be controlled. There

is much less concern over the demo¬

graphic explosion yet, so far, we donot know how to control it."

While carrying on his scientificwork, Dr. Auger wrote and broadcastregularly for the public. He had over300 articles published in Lectures pourTous, a large-circulation French maga¬zine, and he helped bring science intothe programmes of the French Radioand Television Service. It was for this

aspect of his career that he was

awarded the Kalinga Prize for thePopularization of Science, founded in1951 by an Indian industrialist, Mr. Bi-joyanand Patnaik, and administered byUnesco.

When he accepted the prize atUnesco House, Dr. Auger discussedthe responsibilities of the scientificpopularizer and, at the same time, the

attitude of the general public towardsscience (see article page 4.) Somemembers of the public are enthusiasticabout the intellectual adventure of

basic science, others want to hear of

the feats of technology, but there is athird category that looks upon science

with anxiety. The first two requiremainly food for thought, said Dr. Auger,but the third should be given theunvarnished truth without dramatic

trappings.

What the popularizer must do atall costs Is to transmit knowledgerather than create myths. Dr. Augermade a case for the humility of sciencethat seeks truth by building a theoryor model, then testing it by experi¬ment. The mythmaker, on the con¬trary, explains events by bestowingsuperhuman virtues upon objects. Thetest of a scientific theory is its uni¬

versality, but this does not concernthe mythmaker who can invent a newexplanation for every new event justas the Romans had a god for everyphenomenon.

Dr. Auger observed that all bar¬riers between disciplines are nowdown just as they were in that scien¬tific "community" of his childhood.The unity of structure of the universeis becoming apparent, we can under¬stand the stars only if we can under¬stand the atom and nuclear energy.Even science and art are drawing

closer. The hope of science lies inthis universality.

15

THE ENIGMA

OF THE THRACIANS

Tomb discoveries on the plains of Bulgariashed new light on a civilization of huntersand goldsmiths dating back 3,000 years

Right, a hunting scene

decorating part of a linkfrom a Thracian silver-giltbelt of the 4th century B.C.

The chase figures promi¬nently in the decorative artof the Thracians, who were

great horsemen and hunters.Unearthed near Letnitsa

(central Bulgaria) the com¬

plete belt link is inset withpearls forming three panels.In this one the archer's coni¬

cal cap and fringed tunic andthe attitude of the horseman

urging his mount to jumprecall similar figures dis¬covered in Persia. The Thra¬

cian craftsman who made

the belt during the 4th cen¬tury B. C. may have drawninspiration from Achaemenidart of the same period.

Left, a silver knee-pieceembellished with a human

face (350-300 B.C.) foundin a Bulgarian burial moundat Vratza. When pursuing

dangerous game such aswolves and bears, Thracian

hunters wore protective ar¬mour including knee-pieces

of this type.

by Magdalina Stancheva

HE Thracians and their

culture pose one of the most fascinat¬ing enigmas in the early history ofEurope. Today their ancient territorieslie within the frontiers of Bulgaria,Greece and Turkey-in-Europe; andthough the Thracians bequeathed theircultural heritage to Europe, they werebound to Asia by strong and abidinglinks.

Mention of the Thracians may bringto mind the name of Spartacus, wholed a great slave uprising againstancient Rome, or passages fromHomer's Iliad. It may also conjure upan image of gold treasures or of aregion in south-eastern Europe.

As early as the 13th century B.C.the Thracians crossed the narrow stripof water separating them from AsiaMinor and indisputable traces of theirpresence have been found in theearliest archaeological layers at the

MAGDALINA STANCHEVA Is one of the

leading archaeologists and philologists ofBulgaria. Head of the Archaeological Depart¬ment of the Historical Museum in Sofia

for the past twenty years, she has carriedout Investigations at all the major archaeo¬logical sites in her country. For her pioneerwork on Serdica (the ancient name for Sofia)she was recently awarded the Sofia Prize.

site of Troy. In this way they occupiedareas of contact between the two

continents and remained open to in¬fluences from both East and West.

Answers to some of the mysteriessurrounding the Thracians are todaybeing found in the burial and settlementmounds that dot the Bulgarian land¬scape. Archaeologists excavating themany cultural layers of the settlementmounds have uncovered strata datingback to the Neolithic and Bronze Agesand found apparent evidence of linkswith Thracian and pre-Thracian tribes.Much painstaking work remains to bedone, however, before it is possibleto determine the date from which the

inhabitants of these settlements can

be considered with certainty as Thra¬cians.

Altogether, over 15,000 mounds havebeen charted and listed by Bulgarianarchaeologists and are now protectedby law as important cultural relics.What do they hide? Some may beprincely tombs rich with priceless ves¬sels and jewellery; others may besoldiers' graves, containing merely anurn full of ashes and a bent iron spear.There is work enough for generationsof archaeologists.

But it is not always the biggestmound that conceals the most valu¬

able treasure. Two years ago, duringthe construction of a canal near Sofia,the scoop of a mechanical shovel bitdeep into a slight rise in the groundand brought up in its load of earth a

clay urn, a copper cauldron and a hugegold bowl. With its exquisite shapeand ornamental flutes and spirals, thegold bowl, dating back to just overone thousand years B.C., was clearlythe work of a skilled goldsmith.

Prior to this discovery the onlyknown gold vessels from this periodof Thracian history were those foundnear the village of Vulchitrun, in north¬ern Bulgaria, and known as "The Vul¬chitrun Treasure". More than 14 kilo¬

grammes of gold had gone into themaking of these vessels of variousshapes and sizes, which it seems wereintended for ritual use, possibly inconnexion with sun-worship.

From about 500 B.C. the Thracian

principalities flourished, and many ofthe Thracian tribes united to form the

powerful kingdom of Odrysae. Theytraded with Greece and with the Greek

colonies established along the shoresof the Aegean and the Black Sea.Greek influence made itself felt amongthe ruling classes. But it was a two-way traffic and Thracian culture in turnleft its imprint on the arts and craftsand even the cultural life of the Greeks.

One example of this was the spreadof the cult of the god Dionysius whichwas rooted in Thracian religion. Ano¬ther is the tragic story of the legendaryThracian poet and musician, Orpheus, ^which became a familiar theme in 1 /Greek and Roman poetry. ' '

In those prosperous times, Seutho-polis, the capital of the kingdom of

CONTINUED PAGE 20

ENIGMA OF THE THRACIANS (Continued)

THREE-HEADED

SERPENT

This three-headed serpent, left, is oneof the fabulous beasts that decorate

silver-gilt plaques, dating back to the4th century B.C., found at the vil¬lage of Letnitsa, northern Bulgaria.Other plaques bear scenes of every¬day life. Measuring between 4 and8 cm., each plaque has a ring on theback by which it was attached tothe straps of a horse's harness.

OLDEST BULGARIANGOLD TREASURE

Dating back to before 2000 B.C., the oldestgold treasure yet found in Bulgaria consistsof a cache of 44 rings found at Khotnitsa,Tirnovo district. Archaeologists are puzzledby these curious objects, made of solid goldand polished on one side only. Someconsider them to be idols, the two smallerholes representing the eyes and the larger,central hole the mouth; others think that theywere ornamental medallions suspended bythongs threaded through the smaller holes.

LIBATION BOWL

One of the finest items in the treasure trove discovered at Panagyu-rishté, 70 km. south-east of Sofia, is this 4th-3rd century B.C. goldlibation bowl. Detail left shows the outside of the bowl richlydecorated with three concentric circles of negro heads and a circleof acorns. These motifs are repeated on the inside of the bowl. Photobelow shows complete bowl (measuring 3.5 cm. high by 25 cm. across)which was fashioned by craftsmen of Lampsakos, one of the Greekcolonies that flourished on the coast of the Sea of Marmara.

ENIGMA OF THE THRACIANS (Continued)

20

Odrysae, named after its ruler Seu-thes, was built on the model of the

Greek towns In the valley of the riverTundja. Here, where the king's palacewas built, archaeologists found .aninscription in Greek giving the nameof the town, among the ruins that hadlain undisturbed for centuries beneath

the soil of the Valley of the Roses.

Two other magnificent examples ofThracian art were also discovered in

the Valley of the Roses: the Panagyu-rishté treasure and the Kazanluk tomb,burial place of a Thracian chieftain.

The Kazanluk tomb is a small build¬

ing with a narrow passage and a roundchamber covered with a cone-shapeddome (see "Unesco Courier", June1968). The walls are covered withsome of the most perfect paintings inEurope, the finest to come down to usfrom the fourth century B.C.

In the centre is depicted the classicalscene of a funeral feast with the chief¬tain and his wife seated at a well-laden

table. The wife has placed her handin that of the Thracian prince, her headis bent, her exquisite face expressesgrief at the parting. Around them areservants bringing gifts, and leadingthe dead chieftain's favourite horses.

The atmosphere of solemnity is soften¬ed by these touches of intimacy.Up above, in the dome, four-in-handchariots are being raced.

The paintings reveal the hand of ahighly trained and skilful artist, pos¬sibly a Greek, but the spirit and thecontent of the scenes depict Thraciancustoms and the life of a princelyThracian home.

The set of gold wine vessels, orrhyta, found near Panagyurishté isanother example of the penetration ofGreek art. The rhyta are made in avariety of forms: the heads of womenor animals, amphoras with mythologi¬cal scenes, the forequarters of a goat.The flat cup (Phiale) Is ornamentedwith concentric circles of small negroheads in relief (see photo page 19).

This exquisite work was made inthe city of Lampsakos on the coastof Asia Minor.

Many other masterpieces have beenunearthed in recent years and namedfrom the places where they werefound: the Loukovit, Letnitsa, Vratsaand Stara Zagora treasures. Gold orsilver, they were almost all made byThracian goldsmiths.

Many of the objects found in tombswere made to ornament the trappingsof horses, for Thracian funeral cus¬toms included the burial of the deadman's horse in the same mound. AThracian warrior's proudest posses¬sions were his horse and the arms hebore, and their decorations were trueworks of art.

Figures of animals usually formedpart of the decoration. Skilful styli-zation transformed their strained andcontorted bodies into intricate entwinedornaments extraordinary combina¬tions of four-footed animals, birds andreptiles.

This art, which was possibly alienand incomprehensible to the Greeks,was the product of centuries of dev¬elopment, during which its forms attain¬ed a remarkable degree of stylization,without, however, losing their initialtraits. Some researchers have re¬

cently looked for the sources of thisart in pre-Achaemenid Iran, where newfinds from Luristan show interestingsimilarities with those of Bulgaria.

Man, the warrior and mounted hun¬ter, is the main subject of the decor¬ative plaques found near the villageof Letnitsa. In contrast to the animal

forms, the human figures appearrather stiff and clumsy. The engravershows little concern for proportion, butcarefully records details of the chain-mail and weapons, and notably theface, which is large and expressive.Human and horses' heads, unconnec¬ted with the rest of the composition,are boldly placed in the spaces aroundthe figures.

HE variety and abundanceof finds in the tombs is linked with theThracian attitude towards death. The

Greek historian, Herodotus, (5th cen¬tury B.C.) described the Thracian cus¬tom of lamenting over a new-bornbaby, but of bidding farewell to thedead with feasting and merrymaking.This attitude to life and death musthave expressed the hardships ofeveryday life, which led the Thraciansto the ritual rejection of life and tothe concept of death as a deliverance.

Having become a deeply-rooted tra¬dition, this attitude accounts for the

extraordinary magnificence of thefunerals of the rich. No less than five

richly adorned chariots together withthe horses required by the ritual werefound buried near the tomb of theirmaster in a mound not far from the

town of Stara Zagora.

In the early years of our era the

A lovely example of Thra¬cian art, this 16 cm. high,stylized stag of the 7thcentury B.C. was found atSevlievo (Bulgaria). Thepoints of the antlers arecarved in the form ofbirds' heads.

hand of Roman rule was laid heavily onthis martial and freedom-loving people.The prolonged resistance to Romanconquest was marked by acts of des¬perate courage, which we learn aboutfrom Roman authors. Far from his

native land (today in south-western Bul¬garia) Spartacus the Thracian becamethe leader of the greatest rebellion ofslaves in history.

But in time many Thracians joinedthe Roman army and administration,while the nobles preserved their pri¬vileges and their estates, as inscrip¬tions on the Thracian villa-castle near

Stara Zagora and burial finds of theRoman period affirm.

Yet the spirit of Thracian culturesurvived, and although luxurious tem¬ples to the gods of the Graeco-RomanPantheon were built, shrines of Heros,the Horseman, the beloved and mosthonoured Thracian deity, are still foundscattered over the Thracian lands.

Like his worshippers, Heros was ahunter and warrior. He is associatedwith the powers of life as well as theunderworld and he was the god of bothfertility and death. Bendis, the foresthuntress, who is identified with Arte¬mis-Diana, the huntress, is Heros'feminine incarnation.

In the following centuries the Thra¬cians had to endure the invasions of

the Goths, the Visigoths and the Huns.They withdrew many times to the hillsand again returned to the ravagedplains, into which, in the sixth century,the Slavs gradually penetrated andsettled. They were the last wave ofthe Great Migration of the Peoples.The surviving Thracians merged intothe new ethnic community formed hereby the Slavs and the Proto-Bulgarians.

Today, after 1,300 years, a distantecho of the Thracian past is still heardin Bulgarian folklore, in those specialfeatures which distinguish it from thefolklore of the other Slav peoples, andwhich are rooted in the ancient historyof present-day Bulgaria.

Drawing of the international communicationssatellite Intelstat III. in operation for the pastfour years. Only three countries to date possesscommunication satellites for radio and T.V.

broadcasts: U.S.A.. U.S.S.R. and Canada. But

many countries and indeed whole regions areactively planning the use of such satellites inthe ii=nr future. Two examples: India willshortly begin an experiment with an educa¬tional T.V. satellite: South America is studyingan ambitious scheme for a satellite to be used

by 9 of its countries. In both cases Unesco isco-operating closely in the planning stages.

"OTT

t /'

Drawing © from " Satellite Communications ". Kokusai Denshin Denwa ¡Co,, Ltd., Tokyo

INTERNATIONAL PROBLEMS

OF TELEVISION VIA SATELLITE

A major debate at Unesco'srecent General Conference

by

Gunnar Naesselund

GUNNAR NAESSELUND is Director of Unes¬co's Department of Free Flow of Informationand Development of Communication. Beforejoining Unesco he was Managing Director andEditor in Chief of "Ritzaus Bureau", theDanish national news agency. He has beendeputy chairman of the International PressTelecommunications Council and was formerlya lecturer at the school of journalism atAarhus University (Denmark).

HE satellite broadcasts of

tomorrow became the focus of thedebate on communications at Unesco's

seventeenth General Conference in

Paris in October-November 1972, al¬most ten years to the day after thefirst authorization given by the Gen¬eral Conference to the Director-Gen¬

eral to undertake studies of the conse¬

quences which new techniques ofcommunication by artificial satellitesmight have on the achievement ofUnesco's objectives.

A series of studies, meetings andnegotiations culminated in a "Declara¬tion of Guiding Principles on the Use

of Satellite Broadcasting for the FreeFlow of Information, the Spread ofEducation and Greater Cultural Ex¬

change", setting out in a Preamble andeleven Articles principles for guidanceof member states in the use and dev¬

elopment of this new technology.

The guidelines were finally adoptedat the General Conference by a largemajority, but the debates as wellas the voting figures revealed aconflict of views which will not be

easily reconciled.

The deepest of these is the basicissue of freedom of expression. Ano¬ther is the authority of organizations

CONTINUED NEXT PAGE

21

A declaration of 11 'guiding principles'

1

2

3

4

5

6

The use of Outer Space being governed by international law, the development of satellite broad¬casting shall be guided by the principles and rules of international law, in particular the Charterof the United Nations and the Outer Space Treaty.

Satellite broadcasting shall respect the sovereignty and equality of all States.

Satellite broadcasting shall be apolitical and conducted with due regard for the rights of indivi¬dual persons and non-governmental entities, as recognized by States and international law.

The benefits of satellite broadcasting should be available to all countries without discriminationand regardless of their degree of development.

The use of satellites for broadcasting should be based on international co-operation, world¬wide and regional, intergovernmental and professional.

Satellite broadcasting provides a new means of disseminating knowledge and promoting betterunderstanding among peoples.

The fulfilment of these potentialities requires that account be taken of the needs and rights ofaudiences, as well as the objectives of peace, friendship and co-operation between peoples,and of economic, social and cultural progress.

The objective of satellite broadcasting for the free flow of information is to ensure the widestpossible dissemination, among the peoples of the world, of news of all countries, developedand developing alike.

Satellite broadcasting, making possible instantaneous world-wide dissemination of news,requires that every effort be made to ensure the factual accuracy of the information reachingthe public. News broadcasts shall identify the body which assumes responsibility for the newsprogramme as a whole, attributing where appropriate particular news items to their source.

The objectives of satellite broadcasting for the spread of education are to accelerate the expan¬sion of education, extend educational opportunities, improve the content of school curricula.

22

T.V. VIA SATELLITE (Continued)

within the U.N. family to deal withthese questions. On the one handare the fears of developing and othernations of being exposed to unwantedprogrammes, over which they have nocontrol. On the other are the obvious

benefits which individual countries

could gain from having access toprogrammes, which would promote theexchange of ideas and knowledge.

All these issues are Interrelated and,

in part, contradictory, which in itselfexplains the complexity of the problemand the conflicts which emerged duringthe General Conference debate.

Broadcasting satellites are a newgeneration of communication satellites,which will make it possible to transmittelevision programmes directly to com¬munity or home receivers equippedwith adaptors and special antennae.

One such installation constructed in

the United States, will be used experi¬mentally to pick up full colour tele¬vision programmes from the NASAexperimental satellite ATS-F, which isexpected to be launched early in 1974.

The cost of these units will be about

two thousand dollars each, for anorder of 300 one for each of the

sites selected for the experiment.Manufacture In large quantities mayhalve the price. Later on the samesatellite may be used for similar pur¬poses over India for a one-year experi¬ment in about five thousand villages.

The United Nations Committee on

the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space isthe focal point within the U.N. familyfor co-ordination of the U.N. activities

in this sphere and has been keptinformed throughout of progress in thepreparation of the Unesco Declara¬tion, but has not yet been able tocomment. It is expected to do so soonwhen two of its organs may have thetext of the Declaration on their agenda.

Meantime, arising from a sugges¬tion by the Soviet Union, the U.N.General Assembly has requested itsOuter Space Committee to elaborateprinciples for the use of satellitesfor direct television broadcasting, witha view to concluding an internationalagreement.

A number of member states at the

Unesco General Conference consid¬

ered that no final decision should be

taken on the presented text until theviews of the United Nations had been

heard. Others remarked that there

was not much point in placing beforethe U.N. Committee a text which had.

not been endorsed and therefore did

not represent a political reality.

A number of industrially developed

countries, including the United States,Australia, Canada and the Fed. Rep.

of Germany, directed their interven¬tions in the first place, towards a de¬ferment of any conclusive Unescoaction. Others, grouping France, East¬ern Europe and developing countries,wanted the text adopted forthwith, and

won by a majority of 55 in favour, 7against, with 22 abstentions.

The United States and others oppos¬

ed the Declaration also on the groundsthat any attempt to regulate by inter¬national principles the use of outerspace for direct broadcasts was aviolation of the principle of freedom ofinformation, and thereby also ofUnesco's own statutes and goals.Some referred to their national con¬

stitutions, which expressly forbade

measures restricting freedom of ex¬pression.

The fear of the unknown and the

uncertainty surrounding a new power¬ful technology at the service of thefew prevailed in the debate. These

We publish below the 11 "guiding principles" of the Declaration on the use of satellite broadcasting, adopted by Unesco'sGeneral Conference on November IS, 1972, following very sharp differences of opinion.

further the training of educators, assist in the struggle against illiteracy, and help ensurelife-long education.Each country has the right to decide on the content of the educational programmes broadcastby satellite to its people and, in cases where such programmes are produced in co-operationwith other countries, to take part in their planning and production, on a free and equal footing.

7

8

9

10

11

The objective of satellite broadcasting for the promotion of cultural exchange is to fostergreater contact and mutual understanding between peoples by permitting audiences to enjoy,on an unprecedented scale, programmes on each other's social and cultural life includingartistic performances and sporting and other events.Cultural programmes, while promoting the enrichment of all cultures, should respect thedistinctive character, the value and the dignity of each, and the right of «11 countries and peoplesto preserve their cultures as part of the common heritage of mankind.

Broadcasters and their national, regional and international associations should be encouragedto co-operate in the production and exchange of programmes and in all other aspects of satellitebroadcasting including the training of technical and programme personnel.

In order to further the objectives set out in the preceding articles, it is necessary that States,taking into account the principle of freedom of information, reach or promote prior agreementsconcerning direct satellite broadcasting to the population of countries other than the countryof origin of the transmission.With respect to commercial advertising, its transmission shall be subject to specific agreementbetween the originating and receiving countries.

In the preparation of programmes for direct broadcasting to other countries, account shall betaken of differences in the national laws of the countries of reception.

The principles of this Declaration shall be applied with due regard for human rights and fundamental freedoms.

considerations were met by the princi¬

pal Articles of the Declaration recog¬nizing that development of satellitebroadcasting shall be guided by theprinciples and rules of internationallaw, in particular the Charter of theUnited Nations and the Outer Space

Treaty; that it shall respect the sov¬ereignty and equality of all States; andthat States shall reach or promote

prior agreements concerning directsatellite broadcasting to the popula¬tion of countries other than the coun¬

try of origin of the transmission. This,of course, would include transmissionsof commercial advertising.

There is no doubt that many States

could reach mutual agreements on thecontent of satellite programmes in thefields of education, science, culture

and information, dealt with in the

Declaration. There would, however,

be other cases where such agreementcould not be reached and where plansfor satellite transmissions would have

to be abandoned or revised consid¬

erably to avoid breach of the Declara¬tion.

Those who would disregard suchconsiderations would expose them¬selves to accusations of violating inter

nationally recognized principles, eventhough the Unesco Declaration is nota binding legal instrument.

Unlike short wave radio broadcasts

across frontiers, TV transmissions via

broadcast satellite will be extremely

difficult to jam. The recognition thatthis situation is made possible expli¬citly by the use of outer space whichis declared to be governed by inter¬national law is seen by some as a

justification for the demand for priorconsent.

The Declaration, it should be noted,

does not attempt to embrace tradi¬tional use of radio waves nor does it

touch the point-to-point communica¬tions that are carried over the INTEL¬

SAT systems or similar future satel¬lite systems serviced by large groundstations, over which governments nor¬mally will have full control.

Two viewpoints are at loggerheads.One holds that there is an infringementof the right of the individual to haveaccess to information regardless offrontiers, and the other, that there is a

violation of the rights of sovereign andindependent states to decide for them¬selves what programmes their peopleshould be exposed to.

There are also those who, while

supporting in principle the right of theindividual to have access to informa¬

tion regardless of frontiers, maintainthat so long as broadcasting by satel¬lite remains a monopoly of a fewcountries this right is meaningless andeven prejudicial to countries withoutaccess to satellites.

The Unesco Declaration attemptedto establish a balance between con¬

flicting views while formulating princi¬ples which would be meaningful andinternationally accepted. As the Gen¬eral Conference debate showed, how¬

ever, full consensus was not achieved.

Meanwhile, the technology is mov¬

ing forward rapidly. The newly launch¬ed Canadian satellite AN1K is trans¬

mitting colour television signals whichmay be picked up in the United States,without hindrance, as well as in Can¬

ada, by means of specially construct¬ed antannae much less expensive thanthe large ground stations previouslyused. Direct broadcast satellites are

already being manufactured.

The world of tomorrow is upon us,and mankind will face it once more in

dilemma, with a mixture of anxiety and

hope.

23

AFRICA

IN THE

STRESS

OF

TECHNOLOGY

T