Fashioning- a Self€¦ · "Genesis" exhibition, but those who, if they do dance the "Antelope...

Transcript of Fashioning- a Self€¦ · "Genesis" exhibition, but those who, if they do dance the "Antelope...

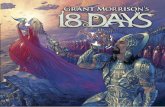

Fashioning- a Selfin the ContemporaryWorld

Notes Toward a Personal Meditation onMemory, History, and the Aesthetics of Origin

ABENA p. A. BUSIAWith sculpture and commentary by ALISON SAAR

y invitation tothe symposiumat the Metropol-itan Museum ofArt was occa-sioned by mywork as a poetand a literary

critic much concerned with issues of per-sonal and group origin, and the ways wetry to articulate those issues in our con-temporary life and work. The peoples Ifocus on are in fact two groups of dis-possessed peoples. Not the peoples wesee dance with elegance and certainty ofpurpose in the films on display in the"Genesis" exhibition, but those who, ifthey do dance the "Antelope Dance," asit's called in Toni Morrison's Beloved, nolonger recognize that they're doing it, orwhat it myans. I am interested in Africa'sNew World children, two groups of them:the long gone and the newly gone, whoseexperiences have been shaped by worldsother than those from which they mightclaim their origins (Fig, 1). I am inter-ested in what myths of origin one doesclaim if one's origins can be seen as"hybrid," and hybrid in often contesta-tory ways,

54

One of the truths "Genesis" made soclear is that we live all the time with mul-tiple myths of origin, or perhaps, as wasarticulated by other symposium partici-pants, we live with myths of multipleorigins. Even societies that consider them-selves cohesive and coherent live withfoundational myths of creation, and ofcivic origins sometimes in tension—and,to recall John Thornton's contribution (p.32), in real political dispute. In Westernterms, for example, we can consider thedistance traveled from the abode of theFuries to Mount Olympus to the law courtsof Athens. The book of Genesis takes usfrom "In the beginning God created" to theExodus of the children of Israel from Egypt.That is foundational; the rest, as they say,is history. For the children of Israel, as forthe ancestors whose representations oftheir divine story were on display in the"Genesis" exhibition, the sense of collec-tive coherence lay in their beliefs and inthe performance of rituals that give coher-ence to those beliefs. Thus the symbols ofthose ritual performances undergird theirsense of identity. The headdress of thedance of the ci warn is as central to theBamana as the appearance of the Maskof Apollo was to the Greeks.

The artworks presented in "Genesis"negotiate two sets of identity, of humanorigins and of social origins. The tensionwe live with in Africa today is often thatwe have many conflicting myths, in par-ticular those of social origin. In additionthe modern nation-states in which we cur-rently live are not coincident with thenations of those myths of origin that wecall our own or that govern our lives. 1 fre-quently have to remind my stvidents thatin terms of origins I am older than mycountry. I was born not in Ghana but inthe Gold Coast, being a pre-independencebaby. For instance, the myths of originthat govern the Bamana have little to dowith the existence of the contemporarystate of Mali in which the Bamana reside.Nonetheless, 1 was struck by the commen-tary at the start of the exhibition thatpoints out that the cl uuirn today hasbecome a national symbol of creativityand possibility. This is a wonderful mani-festation of a recognition that Mali todayis made up of many diverse peoples—Bamana, Dogon, and so on—who have, intheir attempt to become a coherent nation-state, transformed the meaning of an orig-inary set of symbolic representations thatthey did not all initially claim. To give

alrlcanarts • spring2004

At the "Genesis" symposium. Alison Saarreflected on ideas of origin that are expressedin her works (Figs. 1, 3-8).

1. Alison Saar (United States, b. 1956)Detail from Fertiie Ground installation1993Mixed mediaPrivate and public collections

"I sfarted thinking about tfie role a center likeAtlanta played in the slave trade. This was, in aweird sort of way, a calling fo ffie reality ofAfricans being brought to this place with reallyugiy beginnings. It was also really interesting interms of the relationship with nature as well aswith the agriculture that was set up here.Therefore, 1 created another mythology aboutAfrican slaves coming here to the United Statesand the relationship to the agricultural issues ofslavery, which was a bit of a turnaround fromthe ci wara in terms of being a positive thing.Here it was a negative thing; it was cruel, andoften a successful crop meant twice as muchwork There is this topsy-turvy that turns thepositive aspects of agriculture upon ifs heed."

spring 2004 - afrtcanaris

another example, the borders of the em-pire of the Golden Stool reached far beyondthe administrative region of Asante inpresent-day Ghana, and also had noth-ing to do with the borders of the modernnation-state, whose legal regulations andofficial decrees circumscribe our lives.Yet today the world over, "kente cloth" isrecognized as "Ghanaian," not necessar-ily Asante (or Ewe). In order to keep thecontemporary state together, we are all,in our various nation-states, fashioningmodern myths of liberation, of civic ori-gin, of identity. Even if they do not alwayshold and do not supersede the oneswhich keep together a different fabric ofethnic community, we all still strugglewith myths and symbols of origin andcommunity when the make-up of thatcommunity changes.

For those of us late-twentieth-centuryAfricans occupying multiple spaces offaith, place, and even time, trying to giveconcrete expression of our sense of ori-gins can be a challenge. I subtitled mypaper "Memory, History and the Aesthet-ics of Origin" because what I am strug-gling with is the question of fashioninga self for Africans in a contemporaryworld, and the extent to which, in our

contemporary world, that sense of self isdependent on memories which are bothpersonal and collective, and a historywhich is both personal and national. Thisstruggle is not new. In the context of theinheritance of myths—whether creationor foundational, internal to Africa orthrough conquest by Europe—these mythscan be seen as radically and ideological-ly in conflict. In the exhibition we aretold that in the wonderful piece calledAdoratrice, or Worshiper, Paul Ahyi, a con-temporary Togolese artist, is attemptingthe refusion of forms at a crossroads oftradition between the West and the restof us (Fig. 2). The explanatory quotationfrom Ahyi: "Modern Africa should be acontinuation of ancient Africa withoutdisjunction, rupture, or relinquishing ofvalues that belongs to us." The artist'srecognition of the question of continu-ity without disjunction or rupture is im-portant to note. But note also his concernwith the transcendence of what he callsethnic boundaries, because his Adoratriceis the stylization and modernization of aci wara headdress, and as he is TogoleseI doubt that he is Bamana or Dogon.This is very important in terms of boththe attempt to create continuity and to

55

resist certain kinds of disruptions: thesymbolic iconography that Ahyi uses tocreate a sense of continuity is not thesymbolic iconography one would assumethat he would look at, but it is still onewe all recognize.

The question of origins, mythical andpersonal, remains a driving force in boththe contemporary art and the contem-porary literature of Africa, and of Africain the New World, desperately in needof sustaining roots. In the literature, thisquestion has been responded to in ahost of ways by many different writersand thinkers.

Derek Walcott's essay "What the Twi-light Says—An Overture," a celebrationof the twenty-fifth anniversary of thefounding of the Trinidad Theatre Work-shop, originally appeared as a preface tohis collection Dream on Monkey Mountainand Other Plays (New York, 1970). Theessay frames his meditation through awalk across his island. Walcott observesthe peoples that he, his brother, and theother actors of the Trinidad Theatre Work-shop were hoping to represent in theircreation of a new national theater. Hecomments on the poverty of their livesand the impoverishment of their roots inthe onslaughts of history: "the folk knewtheir deprivations and there was no fraudto sanctify them. If the old gods weredying in the mouths of the old, they diedof their own volition."

Almost twenty-five years later, in "TheAntilles: Fragments of an Epic Memory,"his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Wal-cott takes a walk through that same islandand comes to different conclusions. In"What the Twilight Says" he was lookingat people of African descent and noticingwhat was missing—the absence of ritu-als, the impoverishment of the old gods.In "Antilles" he is looking at the EastIndian community, who are more re-cently arrived on the islands of Trini-dad and Tobago. The Indians broughtwith them their remembrance and therituals of their myths of origin, whichthey still practice. Here Walcott observesthe presence rather than the absence ofthose rituals.

For a long time it was believed that theproblem for the dying old gods was theycould not, or would, not, endure the Mid-dle Passage and could only be artificiallyresurrected in the New World. Today weknow that Is not true. They walk amongus everywhere in many forms, from thepractitioners of the Yoruba religion inBrooklyn to the devotees of Santen'a or ofVodun in Brazil and Haiti, but they havecome to wear different masks—like thesculpture of Alison Saar (Fig. 3),

The question for Walcott and his gen-eration, however, was of old gods in-voked to represent a precolonial mode ofexistence—ancient Africa as recover)' andresistance. The writer struggles with thisissue, and as he casts his mind back to the

56

2. Paul Ahyi (Togo, b, 1930)Adoratrice1981 :Monotype168,9cm X 44,5cm (66 1/2" x 17 1/2")Collection of A, Vitacolanna

The Togolese artist Paul Afiyi sees himself as

responsible for imbuing traditional forms of

Atrican expression with new life. In Adoratrice

(Worshiper), displayed in the "Genesis"

exhibition, Ahyi pays tribute to the vital force o

ci wara. the divine agent from the Bamana

people's account of genesis that confers the

knowledge essential to human sustenance.

irricanarts

foundation of the Trinidad Theatre Work-shop, he recognizes that the New Worldthey were making had to be in oppositionto the one in which they had been en-slaved. Their dignity therefore lay in mak-ing the world anew with the scarcelyremembered tools of a prior identity.

Yet that those gods whose inevitabledeath Walcott laments have lost theirsacral force is not at all a foregone con-clusion. Walcott worries that New Worldpeoples are caught in the twilight be-tween old gods dying of their own vo-lition and a new God perforce serveddead so he may not be tempted to changehis chosen people. Both these worriesare, for some, ungrounded. The old godsare still worshipped. As Walcott himselfacknowledges when speaking of Soyin-ka's plays, "Ogun is not a contemplativebut a vengeful force, a power to be pure-ly obeyed" ("What the Twilight Says," p.9). Even when Ogun is not worshippedwith the full force of a devotee's exclu-sive faith, his rituals are still performed,and these rituals remain an inspiringmetaphorical force, even to those whoare not devotees. An old god is not nec-essarily a dead god; it's just that onthe one hand, acolytes may now comefrom unexpected places—not Benin, butBrooklyn—and on the other, those peo-ple you might expect to be his childrenhave become apostate, so many liba-tion bearers now make their supplica-tions through the Virgin Mary and notAssase Yaa.

One can read Kamau Brathwaite as anacolyte from Jamaica. When I first readthe great poems of "Masks," the centralcollection of his Arrivants: A New WorldTrilogy, I was stunned to discover that hewas not a Ghanaian. In those poems hecaptures so completely the familiar ritualcadences of Akan. For example, throughthe rhythm of his language, he evokesthe sound, the occasion, and the world-view of fhe people he is representing, asin his prelude to the opening poem se-quence, "Libation";

IPreludeOutof thisbrightsun, thiswhite plaqueof heaven,this leaven-ing heatof the sevenkingdoms:Songhai, Mali,Chad, Ghana,Tim-buctu, Volta,and the bitterwastethat wasBen-

m, comesthis shoutcomesthis song.

He goes on in that prelude first topour the libation, then to make the drumthrough which the voice of the gods mustspeak; he cuts the sacred tree, he killsthe goat, he bends the sapling twigs, andfinally, the drum completed, he makesthe gong-gongs.

The Gong-Gong

God is dumbuntil the drumspeaks.

The drumis dumbuntil the gong-gong leads

it. Man madethe gong-gong'siron eyes

of musicwalk us through the humbledead to meet

the dumbblind drumwhere Odomankoma speaks:

IIIAtumpan

...Odomankoma 'Kyerema saysOdomankoma 'Kyerema saysThe Great Drummer of

Odomankoma saysThe Greaf Drummer of

Odomankoma says

that he has come from sleepthat he has come from sleepand is arisingand is arising

like akoko the cocklike akoko the cock who cluckswho crows in the morningwho crows in the morning

we are addressing youye re kyere wo

we are addressing youye re kyere wo

listenlet us succeed

listenmay we succeed...

In this incredible poem, you feel thegathering of the assembly until there isnothing left but for Odomankoma tospeak.

The power of the poem reminded meof possibilities, made me eager to hearagain the cadences of my youth throughwhich the whole world—divine, com-munal, and familial—was marshalled toorder. When I discovered that poem Iwas twenty years old and beginning exile,for the second time.

So I wish to speak here of the secondgroup of people I referred to, people likeme, the newly gone. Though in my case,apostasy may be too strong a word, mywork on the question of idenfity has beenmotivated by the reality ot' exile. Morethan half my youth between the ages ofsix and thirteen, and eighteen and twen-ty-five, were spent in exile away fromhome. The desire, or perhaps the need, towork through this toward an understand-ing of the poetics of exile has been hardto exorcise, though I have discoveredso msny poets along the way grapplingwith the same issues^Czeslaw Miloszin "Bypassing Rue Descartes" ends upkilling a sacred water snake and accept-ing that "what [he has] met with in lifewas the just punishment/Which reaches,sooner or later, everyone who breaks ataboo." At what point does the acquisi-tion of new knowledge or a new Faithmake you, individually or collectively,forget, and what call do you hear to makeyou remember again, and how?

In my case it was indeed the discov-ery of a number of people on similarjourneys that made me remember. Someof the most confident voices to quellwhat I consider the "Walcottian" angstabout the persistence of old gods are tobe found here in the United States. I wouldlike to refer to the phrase that KwameAppiah used in his symposium talk; "thecontext of exclusion" (Fig. 4). Africans inthe New World are having to shape aworld precisely because they are sojourn-ers in a land they are trying to maketheir c)wn, but whose originary myths ex-clude them.

Whether African Americans or BlackBritish, their existence is excluded by themyths that support the notions of thosenations as states. Therefore, in the playsof August Wilson or the novels of ToniMorrison and Paule Marshall, or the poet-ry of Grace Nichols, we have a militantreclamation of the rituals of remembranceto those gods in whose practices theyonce recognized their own faces. Theirworks are witness to the endurance at leastof rituals of remembrance and the formsthey take. However attenuated these ritu-als may be becoming, they are still herefor us to celebrate in the form of the ringshout or the stories they tell. For AlexHaley, for example, the ritual lay in thepassing down of the stories inheritedfrom his mother's family. The artistic ges-tures are multiple.

In my own case, poetry itself becamemy ritual. I did notset out to write a poet-ry book. Testimotiies of Exile simply grew

57

out of the experiences of my life, fromchildhood on. When I sat down to collectthose poems together after a lifetime ofrandom writing, I realized they could begrouped into various discrete sections.The first section, "Exiles," is a group ofpoems that deal with exile in the morenarrow sense of political exile—coupsd'etat and the loneliness of wanderingaround the world. The second section

•is a collection called "Incantations for'Mawu's Daughters." These are poems

58

HOBERT P4CHEC0. ©200O. THE J. PAUL QETTY TRUST

about being a woman, being a daughter,being a sister, being (or not being) in love.The poems mediate between the vulnera-bilities and strengths that have arisenfrom the condition of being a child and awoman in exile, many of them, includingthe recognition of the goddess Mawu as aforce of power and inspiration, inspiredby conversations with and the strength ofmy mother. The last section, "Altar Call,"is a collection of specifically sacred verse,sacred verse that springs from my testa-

3, Alison SaarAfro-di(e)ty. from the exhibition "Departures: 11Artists at the Getty"200QMixed-media installation304,8cm X 274,3cm x 274,3cm (120" x 108" x 108")Private collection

"This piece is also Yemaya, which I did for anexhibition at the Getty Museum that invitedeleven artists to respond to the coliection. Atthe risk of offending people, much of the GettyCollection leaves me a littie flat, but I wasalways intrigued with their antiquities. When youfirst walk into 1heir antiquity galleries there is aHercules figure complete with his lion's skin inone hand and his club in the other. I was think-ing, 'What a drag that these heroic Western fig-ures are ah about bludgeoning and conqueringand killing opponents.' It made me think of thestory ot hooking up with the Amazon queen,and she's real sweet and she gives him thisgirdle and he bludgeons her to death. Whatkind of way is that to behave? Which led me tothink in terms of my own idea of a heroine,which is retleoted in this depiction of Yemaya.She stands in a bucket of water, she holds afan which is a mirror, and in her hand is silktabric which comes out and weaves aroundpillars of salt that are supporting basins ofwater. It you look closely at her abdomen thereis a mirror, and if you look into it you seeyourselt in her womb and you ultimately see heridentity as your mother,"

atrican arts • spring 2004

4, Alison SaarTobacco Demon, detail from Fertile Groundinstaliation (see aiso Fig, 1)1993•Wood, tin, miscellaneous objectsApprox, 71cm {2B"}High Museum of Art, Atlanta

"I fashioned this pisce affer an overseer—oftenthere were black overseers, which was anotherbetrayal. His suit is made out of tobacco leaves.He holds a sickle in one hand and a chain in theothef. People often say he looks like a pusher,evoking a narcotic, dark side of tobacco,"

spring 2004 - alrican aris

ment of faith as a Christian, and it is thispoint that I wish to stress.

The question of being a Christian is ofcourse, for a person of faith, not experi-enced as a question of exile. But in thecontext of the "Genesis" symposium itdoes become an issue, a new way of look-ing at the question of faith. The objects inthe exhibition are exclusively informedby African origins, many of which natu-rally predate the arrival of Christianityon that part of the continent. Therefore,for somebody who is a Christian, the ques-tion of the Christian myth of origins doesindeed "exile" one from the question ofthe other sets of origins with which onecould, or should, be familiar. As a child inHolland, I did not hear about the goddessMawu from my Methodist father or An-glican mother.

Therefore the aspect of origins I aminterested in here is the realization thatpeople like me, who are neither practi-tioners nor acolytes nor even deliberateapostates, recognize the power of thoseoriginary mythologies to express through

their images the worldview they lay claimto, which still shapes the social fabricof our lives. I wish to stress the extent towhich those myths of origin have in-deed still informed my idea of family,community, and peoples. In our dailyfamilial lives it is possible that neitherAnthony Appiah nor T will question anaunt who comes to us and says, "Yourfather said this yesterday in my dreams,"or "You must do thus and such to placateyour grandmother because you have donesomething you should not have, and mustredeem your transgressive act."

The key point is always the rituals,and particularly the rituals of birth anddeath. We name our children, holdingthem up to the elements at dawn, puttingwater and alcohol to their lips as we prayfor truth and blessings upon their lives,and do not ask in the name of what godwe perform this rite. We do that, and alsogive them Holy Baptism in church. Wecook festival foods at harvest time andfeed it to the waters and oceans for bless-ing and fruitfulness, then take more of

5, Alison SaarTerra Rosa, detail tram Fertile Groundinstallation1993Wood, Georgia clay106,7cm X 71.1cm X 61cm (42" X 28" X 24")Private coliection

"The queen of the Fertile Ground installation isTerra Rosa. She sits on a mound ot dirt; sheactually comes out ot the mound ot dirt. Shehas dirt in her hands that she crams into hermouth. I started doing research about the act ofeating soil and it not being nutritious in terms otvitamin deticienoy and its lack ot magnesium,iron, and caicium, etc. However, when I talkedto people, especially people living in Atlanta,they would say, 'Don't teil anyone, but when mytamily comes to visit me Irom the farm theybring me dirt and I eat it.' I thought that wassuch a beautiful thing—ingesting the soil thatkept them tied to that iand and that was theirhome, I saw the act of ingesting soil as one thatmade the siaves part of this land and made thispart of their soui, and part of their own historyand ancestry as well,"

that ^ame produce and place it on thealtars of our churches (Fig. 5).

It is part of the nature of being Africanthat the gift of syncretism gives the abilityto live in multiple worlds. My personalmemories are not of old gods; they aregods I can no longer name, but it is theiruniverse I claim. Theirs is the universethat gives shape to the lives of the peopleamong whom I was born and who cer-tainly—wherever in the world I am andwhatever it is I think I am doing—claimme (Fig, 6), Their seasons and symbolicdemands hold almost as much sway asthe Christian calendar or the academicyear. We acknowledge their festivals,whether or not we practice them our-selves ritually. It is not so much that theirmyths of origin have become crucial to mein terms of my own creative impulses asthat the social ceremonies of birth, death,and celebration through which thesemyths are marked give meaning to mylife, a life in which ceremonies and ritualsof remembrance have become increasing-ly important.

In my poems for Mawu, those old godsare metaphors rather than figures of wor-ship (Fig, 7a, b). So I would like to endwith one of those poems to the goddessMawu. The aesthetics that empower orengender it are strategically governed bytheir loss. When 1 invoke the name ofMawu, it signifies an ideal that has helpedinform me and hone my ideas about thepotential of women's creative power andforce for wholeness, rather than as an actof specific worship whose activities Imay not yet know. As a feminist scholar,I regard Mawu as a figure not only of re-•sisting subordination; she is also active,creative, and creating.

60

It is important to recognize that Mawuis the goddess of my mother's peopleand that I first heard her story throughmy mother, an Anglican, When my fatherpassed away in exile and we returnedhome to Ghana to bury him, my moth-er's people came to her to soothe her grief.They took her to the ocean for ritual andcleansing, before St. Mary's Guild, of whichshe is a devotee, came to take her to theAnglican church. For my mother those twogestures were not in conflict, and I knowthe significance of both through her

I have two poems invoking Mawu inmy collection. One is a simple lyric cre-ation poem, "Mawu of the Waters." Theother is more complex and requires anexplanation. It is the only poem I haveever completed in Twi, and thus for merepresents a long journey of struggle,and, as a performance poet, of courage.The language in which I write is Eng-lish. Twi is my father's language. It'sstrange, because I am a professor of Eng-lish, I write in English, and unfortunate-ly I dream in English. English was notthe first or even the second language ofeither of my parents and was spoken byonly one of my four grandparents. Forme it was a long struggle and achieve-ment to write a poem in Twi. (It is notgood Twi, but it is Twi.) It is also a poemthat celebrates synthesis. I was born ofparents from two different ethnic groupswithin Ghana. My mother's language isGa, and amongst her people, one of thenames for the supreme creator, represent-ed as female, is Mawu. This name—saidwith variations of tone and emphasis, asif in Twi, my father's language—has avariation of meaning, all centered aroundthe idea of women giving birth, such as

afrlcanarts - SDr*infl2004

Ma Wo, "I have given birfh," and MmaaWo, "women give birth." Thus fhis poemarises out of the particular circumstancesof my parentage. Using the name of thegoddess from my mother's language, it isa play on words in my father's, on theidea of god and the women created inher likeness as life giving.

The poem begins with birthing sounds,which develop into the play on mama, thealmost universal word for human moth-ers, dividing itself into ma ma, the "I have.

I have," preceding the first ma zoo, "1 havegiven birth." Following this, the ma wo,ma wo, "I have given birth, I have givenbirth," collapses into mawu, the first evo-cation of the name of the goddess, at thebeginning of the poem. The mmm mmm,aaa, birthing soimds start the poem, whichthen take us through variations on "I havegiven birth" and "women give birth,""Mawu has given birth" and so on, allbased on a shift in the tones of the vowelsand the emphasis on the consonants, to

6, Alison SaarTopsy1998Wood, tar, bottles, tin122cm X 40.6cm x 30.5cm [48" x 16" x 12")Private cotlection

"I've done a number of figures with bottlescoming out of their hair. It of course reflectsspirit bottles prevalent in the South, and relatesto tree spirits in Africa as well. Instead of

;. attracting malevolent spirits and keeping themK from you, I interpreted it as containing your

own spirits, your own dreams, and your ownideas in the form of these things hanging abouther head."

spring2004 • alricanarts

the mmmmmm of affirmation and the Al ofjoy and surprise at the close. Whatever theinspiriting forces, all geneses are rebirthsand new beginnings (Fig. 8).

MawulMawommmnim mmmm mnunmmm n:inim mmmmm mm jnmmmmmmmfmnm a

' mma mma aamaaammmmmmaaaaamaaa ,maaaamama mamama mawoma ma womama ma womama ma woma womawu

• mawu ! ''̂ '̂ »inawu are! ma woma woma wommaa wommaa worrimaa womama mawumama mawumama p\awua woa womawu a womawu a womawu a wo womawu a wo womawu a wo mamamawu a wo mamamawu a wo mu

. mawu a wo mumawu a wo mu mamawu a wo mu mamawu a wo mmaamawu a wo mmaamawu wo mmaamawu wo mmaamawu wo mmaamawu wo mmaenmmmmmmmmmmmmm AA!

MawulMawo

mmmmmmmmmmmmmm mmm mmm

• mm mm mmmmmmm mmm a

I

mma mma aamaaammmmmmaaaaaamaaa

-maaaamama motherI, I'vegiven birthI, I've given birthma, I've given birthmama, I've given birthgiven birth

62

7a. Alison SaarCool Maman2001Mixed media304.8cm X 60.9cm x 71.1cm (120" x 24" x 28")Private collection

7b. Alison SaarSmokin' Papa Chaud2001Mixed media304.8cm X 60.9cm x 71.1cm (120" x 24" x 28")Private coileotion

"These two pieces are paired together as twosides of myself. Cool Maman is my rendition ofYemaya. It's curious; when ( was three years oldI fell into a river and thankfully my father quicklyrescued me. I iater had recurring dreams ofthis river trip. It was never a frightening thing; itwas aiways a voyage and it felt like I was beingtaken somewhere. It wasn't until lafer when iread Ben Okri's wonderfui book The FamishedRoad that I began to understand the experi-ence as being torn between two worlds, as thespirit cailing back. So I did both cf these piecesto pay tribute to two spirits who have been veryhelpful in my career and in my life. Yemaya isbalancing ail these domestic things, which forme, as a mother end creative artist, is a reaichallenge. Then there is Smoking Papa Chaud.who is like Ogun. I should state that I work withchainsaws, axes, and many sharp toois. In lightof this I of course felt the need to say thanksthat I have not yet lost any limbs—neverincurred any major mishaps. There is also aside of me that is very aggressive, a side that isvery much about forcing things. This creativeprocess to me is two sided in terms of this veryforceful aggressive manner in which I work andthen this creative, patient side of me where Icreate with ideas and nurture my chiidren."

africanarts • sprinD20D4

8, Alison SaarIrtheritance2003Mixed media132cm X 60.9cm x 60,9cm (52" x 24" x 24")Courtesy of Jan Baum Gallery, Los Angeles

"This small figure is actually the most recent ofall my pieces. It originally came about as adepiction of a story that my mother told me,that when she was three years old her fathercalled her to his deathbed and said that shewas responsible now and had to take care ofthe family That's a heavy thing to lay on athree-year-old girl, I see how that shaped whcshe is today. She is very much in command allthe time. It is really curious for me because Isee that as a wonderful strong point for her. butI see thai it also causes her a lot ot suffering, Ithink that in raising my two chiidren now I amcareful how much to lay on them—this idea ofbeing responsible not only for yourself but foryour family is pretty daunting. This pieceended up being a child Atlas^a female Atlas,The globe that she bears is bound andconcealed. It's questionable whether that is agood inheritance or bad inheritance—weinherit both. We inherit the good and badthings, and we have to deal with them andsupport them regardless,"

mawumawu!oh mawu! I've given birthI've given birthI've given birthwomen give birthwomen give birthwomen give birthmama mawumother mawumother mawuhas given birthgiven birthmawu has given birthmawu has given birth

mawu has borne you [s]mawu has borne you [s]mawu has borne mamamawu has borne mamamawu has borne you [pi]mawu has bome you [pi]mawu has bome masses of youmawu has bome masses of youmawu has borne womenmawu has borne womenmawu bears womenmawu bears womenmawu bears womenmawu bears nationsmmmmmmmmrrtmmmm AA!

sprinn Z004 • airican arts 63